Translate this page into:

Cytomorphology of unusual infectious entities in the Pap test

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Rare entities in the Pap test, including neoplastic and non-neoplastic conditions, pose challenges due to their infrequent occurrence in the daily practice of cytology. Furthermore, these conditions give rise to important diagnostic pitfalls. Infections such as tuberculosis cervicitis may be erroneously diagnosed as carcinoma, whereas others, such as schistosomiasis, are associated with squamous cell carcinoma. These cases include granuloma inguinale (donovanosis), tuberculosis, coccidioidomycosis, schistosomiasis, taeniasis, and molluscum contagiosum diagnosed in Pap tests. Granuloma inguinale shows histiocytes that contain intracytoplasmic bacteria (Donovan bodies). Tuberculosis is characterized by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with Langhans-multinucleated giant cells. Coccidioidomycosis may show large intact or ruptured fungal spherules associated with endospores. Schistosoma haematobium is diagnosed by finding characteristic ova with a terminal spine. Molluscum contagiosum is characterized by the appearance of squamous cells with molluscum bodies. This article reviews the cytomorphology of selected rare infections and focuses on their cytomorphology, differential diagnosis, and role of ancillary diagnostic studies.

Keywords

Cytology

cytopathology

GYN cytology

infection

Pap test

INTRODUCTION

For more than half a century, the Pap test has been an effective way to screen women for squamous dysplasia and carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Although the Pap test is primarily used for detecting cellular and epithelial abnormalities, certain infections are easily detected on the Pap test too. Therefore, various microorganisms that involve the lower female genital tract have been reported in Pap tests. Rare entities that include neoplastic and non-neoplastic conditions (see Table 1 for a list of benign conditions), pose challenges due to the infrequent occurrence of many of these entities in the daily practice of cytology. These conditions may also give rise to important diagnostic pitfalls to be aware of in Pap tests. For example, cases of granulomatous cervicitis due to tuberculosis seen in Pap tests have been erroneously diagnosed clinically and cytologically as squamous cell carcinoma,[1] and cases of pemphigus vulgaris have been mistaken for endocervical adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma.[23]

Recognition of these rare conditions will decrease the potential for misdiagnosis and expedite appropriate management of patients with these conditions. This article reviews and illustrates the cytomorphology of 6 rare infections that may be encountered in Pap tests and focuses on helpful diagnostic criteria and differential diagnoses. A brief discussion on the role of ancillary tests is also included.

GRANULOMA INGUINALE (DONOVANOSIS)

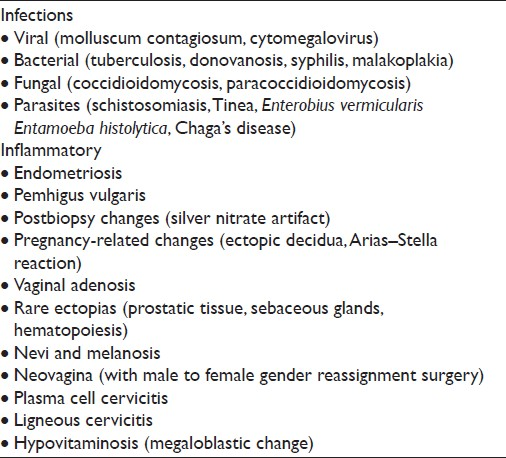

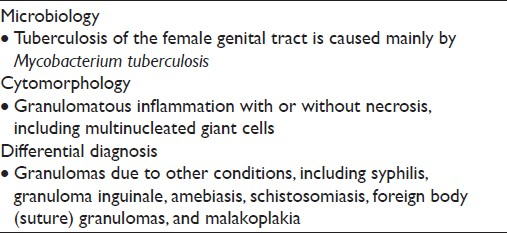

Granuloma inguinale is also known as donovanosis or granuloma venereum [Table 2]. It is a bacterial infection caused by Klebsiella granulomatis, an intracellular Gram-negative bacteria, sometimes referred to as a Donovan body.[4] Donovanosis is different from lymphogranuloma venereum, which is also a sexually transmitted disease, but is caused instead by infection with Chlamydia trachomatis that typically manifests with a painless ulcer and lymphadenopathy (buboes). Granuloma inguinale is transmitted sexually and seen more frequently in Africa and Asia. Infection usually starts as submucosal nodules that may ulcerate producing painless, granulomatous lesions associated with tissue deformity.[4] Infection of the cervix is very rare, and has been described with and without external genitalia involvement.[45] The organism is seen within thin-walled intracytoplasmic vacuoles inside histiocytes. The number of vacuoles within histiocytes varies, and the classic “safety-pin” appearance of these bacteria is not apparent in alcohol-fixed smears. Non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation that includes epithelioid histiocytes admixed with occasional giant cells and lymphocytes is shown in Figure 1. The associated reactive epithelial cells are usually scant, and if there is ulceration one may find marked reparative changes. In such cases, the majority of the Pap test tends to be comprised of acute inflammatory cells without giant cells. The differential diagnosis includes follicular cervicitis, granulation tissue, and other granulomatous diseases, including malakoplakia.[5–7] In follicular cervicitis, tingible-body macrophages may have cytoplasmic inclusions with cellular debris. In addition, the accompanying inflammatory infiltrate with follicular cervicitis is lymphoid predominant and not neutrophilic. In malakoplakia, cytoplasmic inclusions called Michaelis–Gutmann bodies are more dense, laminated and round, compared with Donovan bodies. Ancillary studies that may be helpful include special stains (eg, Romanowsky and Warthin–Starry stains) to highlight Donovan bodies. In such granulomatous cases it is also important to perform acid-fast stains for mycobacteria and fungal stains (eg, Gomori Methenamine Silver (GMS)).

- Granuloma inguinale (donovanosis) in a conventional Pap test. Granulomatous inflammation is shown with epithelioid histiocytes and lymphocytes (a). The organisms (Donovan bodies) can be seen in thin-walled intracytoplasmic vacuoles (circle ) (b). (Pap stain, Mag ×200 in a and ×400 in b).

TUBERCULOSIS

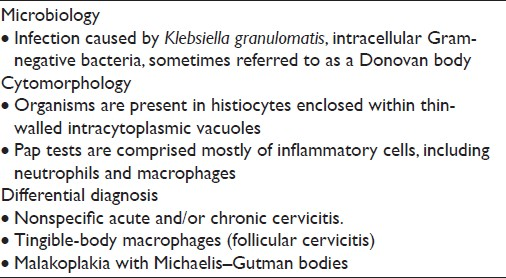

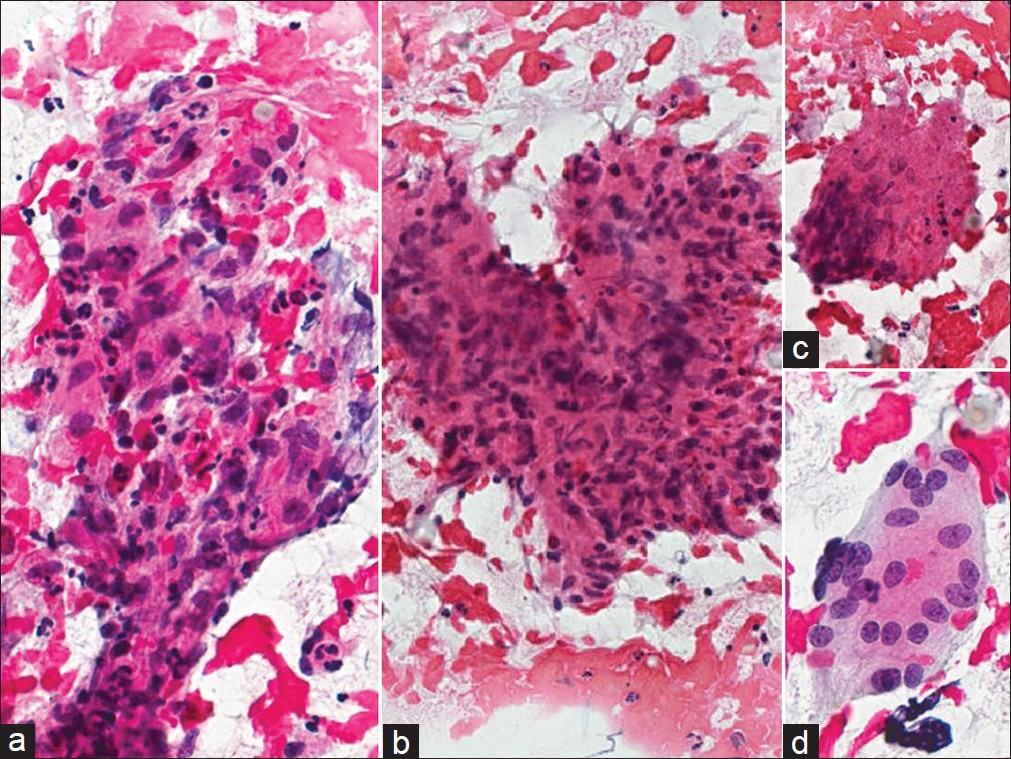

Tuberculosis (TB) is usually secondary to extragenital TB (eg, lung) and is primarily caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis [Table 3].[1] The cervix may become infected through direct spread from the upper genital tract or by lymphatic spread. Occasionally, infection is sexually transmitted from a partner with tuberculous epididymitis or from infected sputum if it is used as a sexual lubricant.[8] TB of the female genital tract typically involves the upper tract (fallopian tubes or endometrium), although infection of the cervix may be seen but it is rare, even where mycobacterial infection is endemic. Patients with genital tract TB may present clinically with amenorrhea, menstrual irregularities, infertility, vaginal discharge, or postmenopausal bleeding. TB cervicitis is often clinically misdiagnosed as carcinoma of the cervix due to the clinical finding of a cervical mass with associated necrosis.[19] Pap tests may reveal granulomatous inflammation with large aggregates of epithelioid macrophages and giant cells present in a bloody and typically necrotic background [Figure 2]. Histiocytes tend to be pale and cyanophilic, contain vesicular, oval nuclei, and often form syncytial arrangements with indistinct cytoplasmic borders. Langhans multinucleated giant cells with 20–30 peripheral nuclei may also be present.[10] A variable number of lymphocytes may be seen, as well as an acute inflammatory exudate. In the appropriate clinical setting (eg, endemic region, clinical history of extragenital TB), the presence of granulomas with multinucleated giant cells in Pap tests should raise the suspicion of TB. The differential diagnosis includes other conditions that cause granulomatous inflammation in Pap tests, such as fungi, syphilis, granuloma inguinale, amebiasis, schistosomiasis, sarcoid, radiation changes, foreign body/suture granulomas, and malakoplakia.[8–10] In addition, histiocytic lesions and granulation tissue can also mimic granulomatous inflammation. Ancillary studies to confirm the diagnosis of TB include acid-fast stains for mycobacteria, autofluorescence, culture, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

- Tuberculosis cervicitis in a conventional Pap test. The cervical smear shown reveals granulomatous inflammation with large aggregates of epithelioid macrophages (a, b) and multinucleated giant cells (c, d) present in a bloody and necrotic background. (Pap stain, Mag ×400)

COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

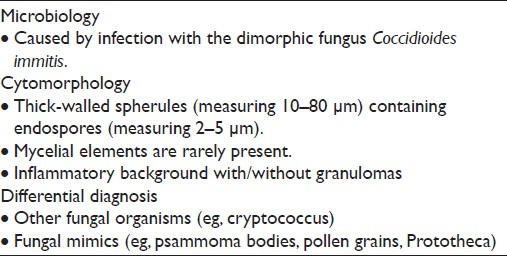

Coccidioidomycosis infection is caused by the dimorphic fungus of the genus Coccidioides (C. immitis and C. posadiasis) [Table 4] and is endemic in the southwestern United States, some areas of Mexico, and in parts of Central and South America. In other regions, this infectious disease is uncommon and the possibility of Coccidioides is often overlooked unless a history of travel to an endemic area is elicited from the patient.[1112] Even a brief stopover in an endemic area can lead to infection. In deserts of endemic areas, the fungus grows several centimeters beneath the soil as mycelia that break apart into air-borne arthroconidia with dry weather. Inhalation of the 2–5 micron arthroconidia is usually the primary route of infection. Once the arthroconidia settle in the new host at body temperature, it transforms into enlarging spherules that can reach 70–100 μm in diameter. Initial infection virtually always involves the lungs, and most patients are asymptomatic or have subclinical disease. However, approximately 40% of patients may develop respiratory tract symptoms, including acute pneumonia, known as Valley Fever, with chest pain, fever, and even hemoptysis.[1112] Pulmonary infection resolves in greater than 90%–95% of patients, without sequelae.

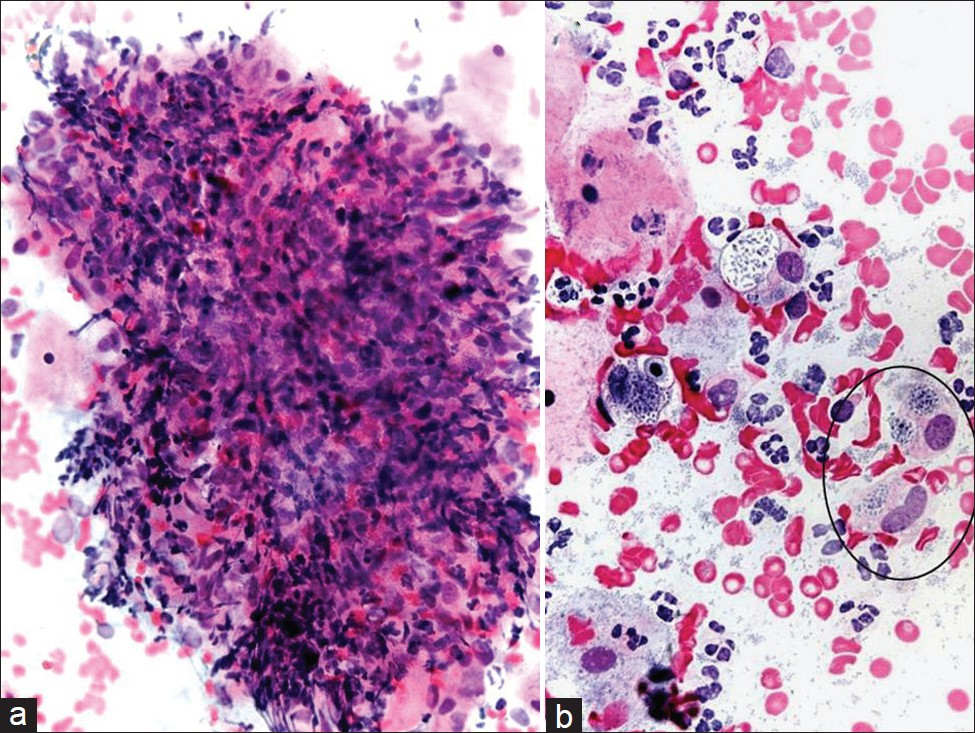

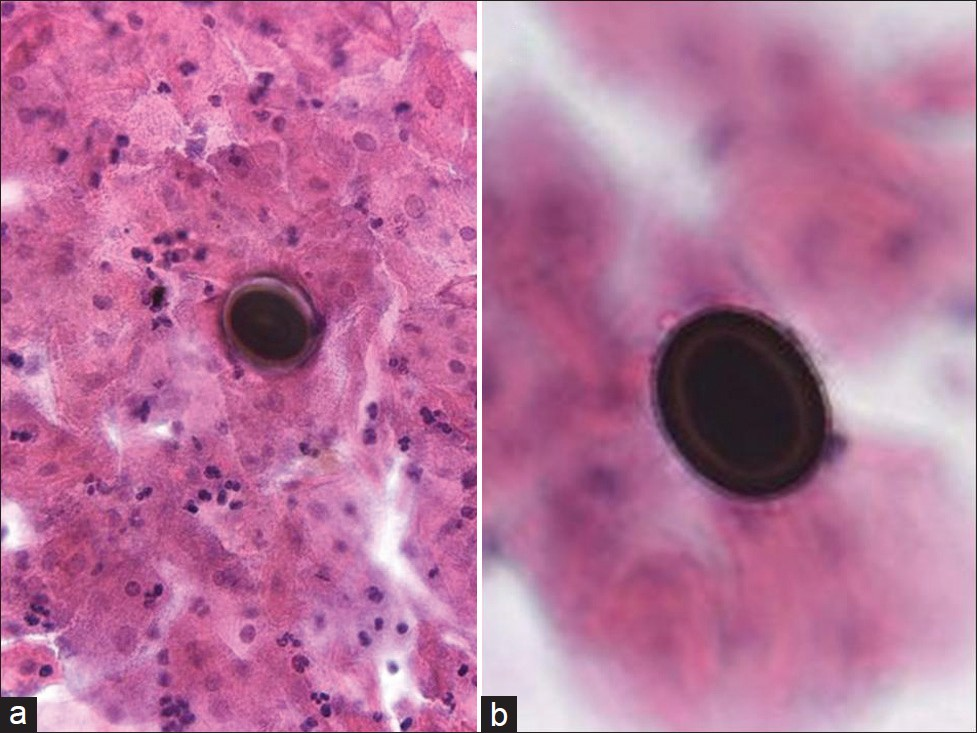

Disseminated infection can occur in less than 1% of cases and very rarely may involve the female genital tract.[13–15] Infection is seen more commonly among pregnant women, individuals older than 65 years, immunocompromised persons, as well as African-Americans, Hispanics, and Filipinos. Mortality from coccidioidomycosis is rare, occurring in fewer than 1% of all infections. Although paracoccidioides in Pap tests has been reported in at least 2 previous publications,[1617] to the best of our knowledge, no coccidiomycosis cases have been reported in a Pap test. As in any other cytology preparation, coccidiomycosis in Pap test material shows large spherules [Figure 3]. These spherules are among the largest structures encountered in cytology measuring up to 100 μm in diameter, have double-contoured walls and may contain up to several hundred small endospores measuring 2–5 μm. The spherules may rupture and empty [Figure 3b] leaving behind large, wrinkled structures that resemble collapsed ping-pong balls. Small scattered endospores in these cases may be seen in the background. These structures are diagnostic for coccidioidomycosis.

- Coccidioidomycosis in a liquid-based (ThinPrep) Pap test. Large round and tear-shaped fungal spherules are demonstrated with some endospores characteristic for coccioidomycosis. (Pap Stain, Mag ×200 in a and ×400 in b)

The differential diagnosis of large spherical structures in a Pap test includes various staining artifacts and other fungal organisms, such as Paracoccidioides, Cokeromyces recurvatus, and the giant blastoconidia of Candida albicans.[1317] Paracoccidioides have large fungal-like elements with a distinct budding pattern characterized by multiple narrow buds resembling a “ship-wheel.” Giant blastoconidia of C. albicans may have multiple buds that are more likely to resemble Paracoccidioides. Such giant forms of Candida may occur after antifungal therapy.[17] Other organisms, including Rhinosporidium seerbi and Prototheca wickerhamii, may be morphologically confused with coccidioides species, but these are found in sites not typical of coccidioides; R. seerbi is found in nasal mucosal lesions, and P. wickerhamii is found in soft tissue sites. The endospores of coccidioides species may be confused with the spores of Histoplasma capsulatum. However, coccidioides endospores are extracellular and do not show the narrow budding seen in H. capsulatum spores. Finally, the presence of coccidioidomycosis in a Pap test may not represent a true infection of the cervix or the vagina, particularly in the absence of significant inflammatory cells or granulomas, but may rather represent colonization of the lower gynecologic tract.[17]

SCHISTOSOMIASIS

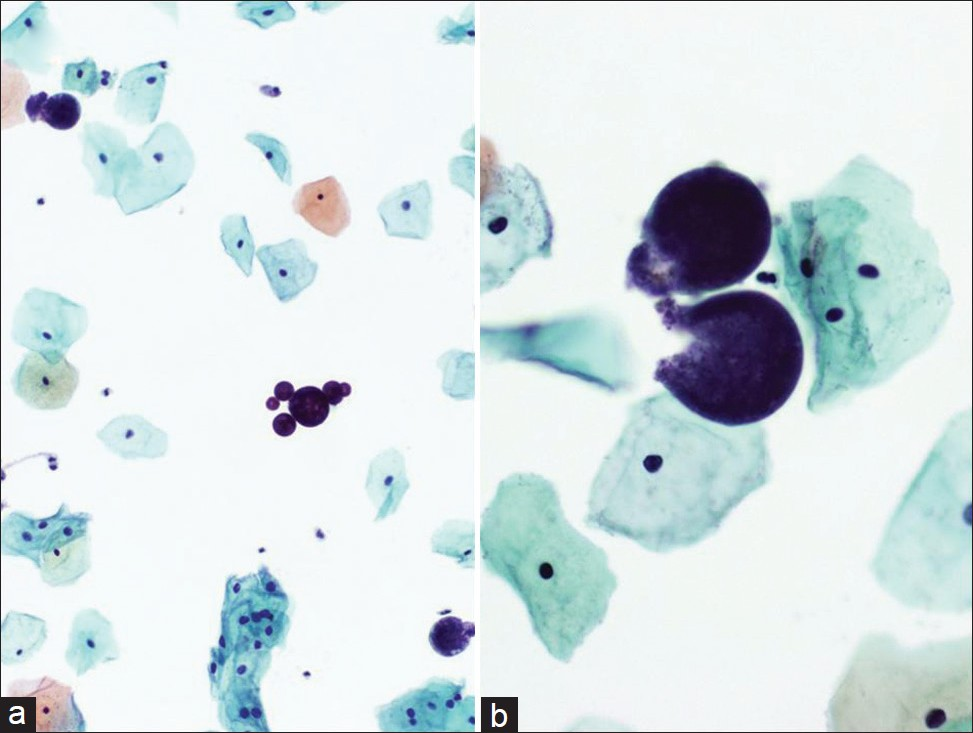

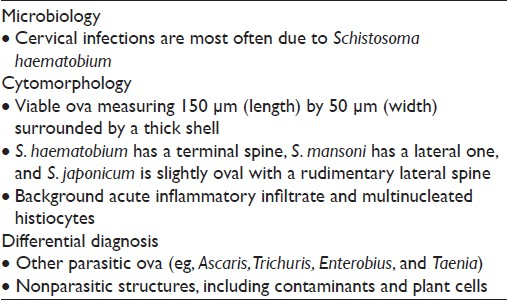

Schistosoma haematobium is a helminth that is a member of the Trematodes (flukes) [Table 5]. This schistosome lives mainly in warm countries, such as Africa and the Middle East and is rare in the United States and Europe. However, this disease is increasingly being seen in developed countries as immigration and international travel increase. S. haematobium eggs are large, measuring 112–170 μm by 40–70 μm, nonoperculate, and have a transparent shell with a characteristic prominent terminal spine.[14] The eggs release miracidia into the water under optimal conditions, which infest an intermediate host, a snail that belongs to the genus Bulinus. In the snail, infective cercariae are produced, which ultimately penetrate the skin and establish infection in their human host. Adult S. haematobium resides in the bladder and pelvic venous circulation. Clinically, most infections are asymptomatic, but schistosomiasis may cause cystitis and ureteritis with hematuria, which on occasion, if untreated, can progress to squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder.[14]

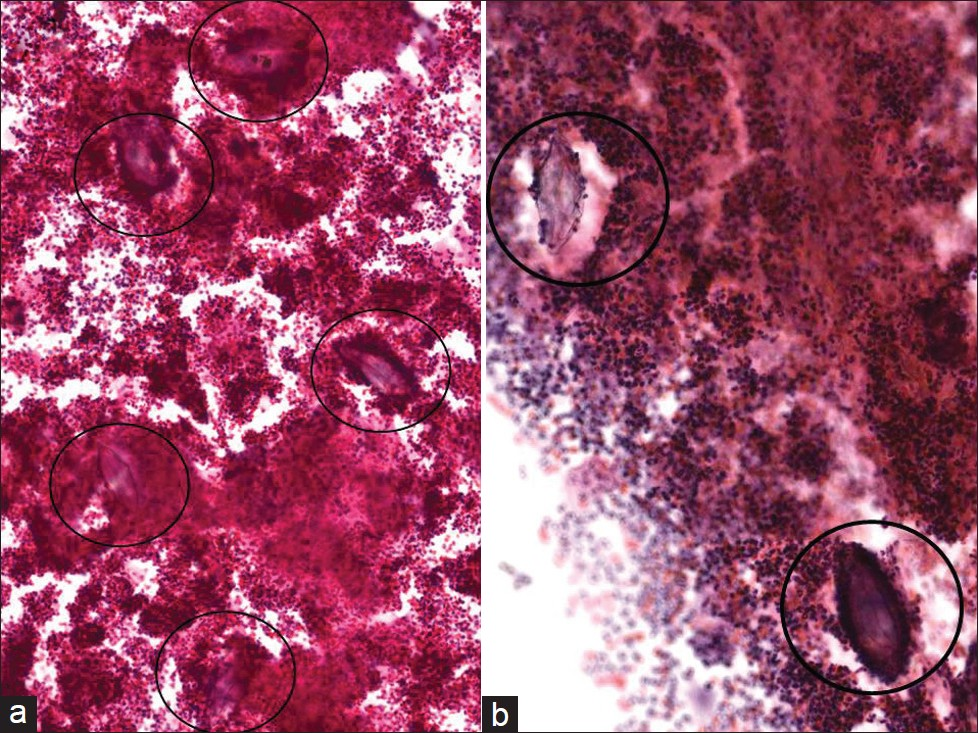

In endemic areas, female genital schistosomiasis ranges from 30% to 75%, where the cervix is the most commonly infected organ.[15] Nevertheless, there are very few reports of Schistosoma infection of the cervix identified on Pap tests. The earliest case report was produced by Youssef et al, in 1962.[18] The organism that most commonly affects the female genital tract is S. haematobium. On cervical smears stained with the Papanicolaou stain, S. haematobium ova may be hard to find as they may be scattered among numerous inflammatory cells [Figure 4]. Ova in various stages of development may be noted, including eggs containing a miracidium that have eosinophilic cytoplasm and hematoxylin-stained granules. The most important pathognomonic finding is the presence of a terminal spine on these ova. Infection of the female genital mucosa with S. haematobium ova creates significantly more vascularized tissue, compared with healthy cervical tissue,[19] which may explain why Pap smears, as illustrated in our case, may be particularly bloody. The case shown here for illustration [Figure 4] is from a patient who lived in South Africa where S. haematobium is endemic in certain areas. Symptoms and signs caused by female genital schistosomiasis are fairly nonspecific and may include irregular menstruation, pelvic pain, vaginal discharge, and bleeding. The infected cervix may become ulcerated, nodular, and friable, thereby clinically mimicking carcinoma.[14]

-

Schistosoma haematobium in a conventional Pap test. Several ova can be seen with a terminal spine (circles) that are scattered among numerous inflammatory cells. (Pap stain, Mag ×200 in a and ×400 in b)

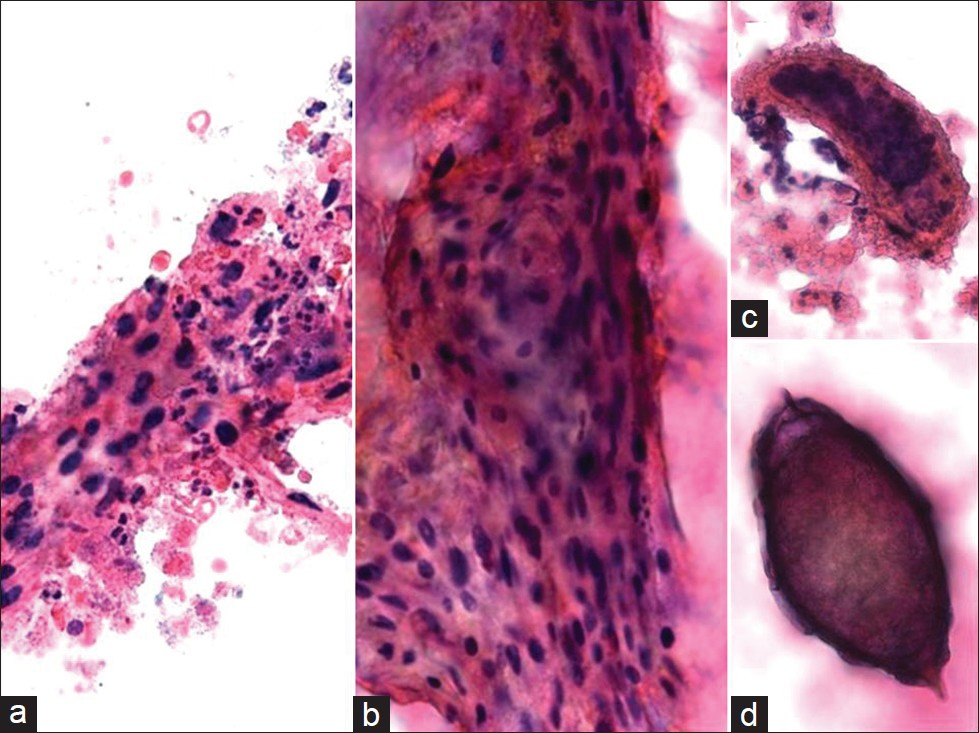

Schistosomiasis in the female genital tract has been associated with an increased risk for spread of sexually transmitted diseases, cervical cancer, infertility, and pregnancy-related disorders.[20] Figure 5 shows a case of both cervical squamous cell carcinoma and S. haematobium diagnosed on a Pap test that was confirmed by biopsy. While the association between urinary bladder cancer and S. haematobium infection is well established, the relationship between this infection and cervical cancer is still under investigation. It is postulated that female genial schistosomiasis serves as a cofactor for human papillomavirus (HPV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections in endemic regions by providing these co-pathogens with a mucosal point of entry.[1421–24] However, it is of interest that in 2 women previously reported with cervical schistosomiasis and who were negative for high-risk HPV, one developed a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion and the other invasive cervical cancer.[25] Our patient shown here with cervical carcinoma and Schistosoma was only 35 years old and, albeit that her HIV status was unknown, this is consistent with the literature stating that patients with cervical cancer and female genital schistosomiasis are often younger than 40 years. Apart from HPV infection, it is plausible that other factors such as chronic inflammation due to infection could accelerate the rapid progression to cancer in this scenario.[20]

- Schistosomiasis and squamous cell carcinoma in a conventional Pap test. The smear shows keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma with necrosis (a, b), and associated scattered Schistosoma ova (c, d) on the slide. Note the terminally located spine (d) in the eggs that is characteristic for Schistosoma haematobium. The background is hemorrhagic. (Pap stain, Mag ×400)

TAENIASIS (TAPEWORM INFECTION)

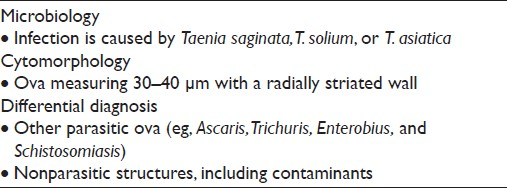

Taeniasis is a parasitic human infection caused by the tapeworm species Taenia saginata (beef tapeworm), Taenia solium (pork tapeworm), and Taenia asiatica (Asian tapeworm) [Table 6]. Infection with these tapeworms occurs by eating raw or undercooked beef (T. saginata) or pork (T. solium and T. asiatica). People with taeniasis may be unaware that they have a tapeworm infection because their symptoms are usually mild or nonexistent. Clinically, the most common presenting symptom is anal pruritus, usually secondary to the eggs that have been laid there. T. saginata (beef) infection results in small intestinal infestation of adult worms (taeniasis). T. solium (pork) infection can also cause cysticercosis as a result of the accidental ingestion of food or drink contaminated with tapeworm eggs from feces. In female patients, the female worms can travel up the vaginal canal, causing infection of the vagina and cervix,[2627] and can even enter the uterus, resulting in endometritis and possibly endosalpingitis. The appearance of Taenia eggs in a conventional Pap test is shown in Figure 6. They are orangeophilic and contain mature larva. The refractile shell is composed of an outer layer and an inner monolayer. Eggs of the various tapeworms can be distinguished by detailed morphologic examination. Taenia eggs measure 30–40 μm and often have a radially striated wall. The ova of Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm) are more commonly seen on Pap tests. However, pinworm eggs are of similar size (20–60 μm), but have no spine and one side that is flattened. Ova may need to also be discriminated from contaminants, such as psammoma bodies and pollen grains. The finding of eggs need not always indicate an infection, however, ova may occur in cervicovaginal specimens as a result of contamination from feces.[2627]

- Taeniasis (tapeworm infection) in a conventional Pap test. Two Taenia eggs (a, b) can be seen in the background of inflammation. The eggs contain mature larva. (Pap stain, Mag ×200 in a and ×400 in b)

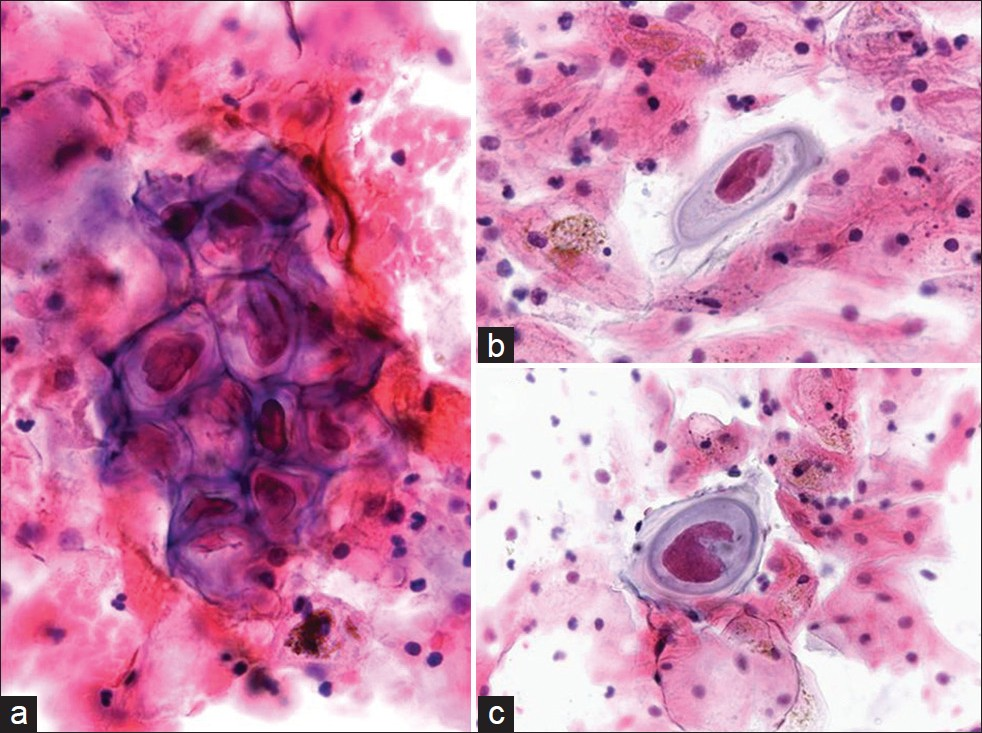

MOLLUSCUM-LIKE BODIES

Molluscum contagiosum (MCV) is caused by a member of the double-stranded DNA poxvirus family [Table 7].[28] The MCV is a viral infection that is highly contagious, but self-limiting. It accounts for approximately 1% of all diagnoses of skin and rarely mucous membrane infections, and affects mostly children and young adults. In adults, the virus may spread by sexual contact.[29–32] Infection follows close contact with an infected person or contaminated object, and results in an umbilicated, dome-shaped papule. Early lesions on the genitalia may be mistaken for herpes simplex or warts but, unlike herpes, these lesions are painless and the virus does not enter latency. Immunocompromised patients may have fulminant infections, such as patients with AIDS who have widely disseminated lesions.[4] However, involvement of the lower female genital tract is very rare.[30] Of interest, oral mucosal involvement by MCV has been reported.[31] Infected squamous cells detected in a Pap test [Figure 7] may also be representative of contamination from a vulvar lesion. The infected squamous cells in a Pap test show characteristic intracytoplasmic inclusions known as molluscum bodies or Henderson–Paterson bodies with a waxy eosinophilic or basophilic appearance. The bloody background may contain acute inflammation, although most molluscum lesions do not have an accompanying inflammatory component, unless they rupture and become secondarily infected. These large intracytoplasmic bodies tend to push the faintly visible nucleus toward the periphery. The differential diagnosis of MCV includes other viral infections with inclusions such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV), signet ring cell carcinoma, and glycogen in navicular cells. Compared with MCV, viral infection with HSV typically results in the formation of Cowdry type A inclusions (eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions surrounded by a clear zone) and/or B inclusions (nuclear molding, chromatin margination beneath the nuclear membrane imparting a ground glass appearance to the nucleus, and multinucleation). Contamination from vegetable material due to lubricants and pessaries has been reported, where vegetable cells may resemble molluscum bodies.[3334] The cytoplasmic inclusion of MCV is distinctive from the single large intranuclear inclusion with small cytoplasmic granules seen in CMV, and is also different from the multinucleation and molding of nuclei seen in HSV. Although the diagnosis of MCV infection can be made based solely on the cytologic finding of molluscum bodies, electron microscopy and molecular techniques (eg, PCR) can be used to confirm the diagnosis.[29] In difficult cases, negative immunohistochemical staining for HSV and CMV can also help. As MCV is recognized as a sexually transmitted disease, specimens should be carefully screened for the presence of other sexually transmitted infections.[32]

- Molluscum-like bodies in a conventional Pap test. The cytology is characterized by the presence of numerous large intracytoplasmic eosinophilic waxy bodies that tend to push the faintly visible host nucleus toward the periphery (a). The background is bloody with a predominance of acute inflammatory cells (c,d). (Pap stain, Mag ×400)

CONCLUSIONS

Rare entities that may be encountered in Pap tests include unusual microorganisms that may infect the female genital tract or that contaminate cervicovaginal specimens. Finding and accurately diagnosing these infections is important, even if their presence does not always signify infection, but rather contamination from vulvar or genital lesions or fecal material. As some of these infections are recognized as sexually transmitted diseases, their presence should prompt such cases to be carefully screened for other sexually transmitted infections. Most of the genital infections presented in this article are rare in the United States and more likely to be seen in developing countries that are endemic for some of these conditions. However, with increasing immigration, travel and the association of some of these infections with human immunodeficiency virus infection these microorganisms may be identified in routine Pap tests. Therefore, knowledge of the cytomorphology of these unusual entities and their diagnostic pitfalls is important. The exact association of some of these infections with dysplasia or malignancy warrants further research.

COMPETING INTERESTS

All author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and granted exempt status. We take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

EDITORIAL / PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2012/9/1/15/97763

REFERENCES

- Cytologic detection of tuberculous cervicitis: a report of 7 cases. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:594-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pemphigus vulgaris of the vagina--its cytomorphologic features on liquid-based cytology and pitfalls: case report and cytological differential diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:832-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pemphigus vulgaris of the uterine cervix: misinterpretation of Papanicolaou smears. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:355-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical smear with intracellular organisms from a case of granuloma venereum (donovanosis) Acta Cytol. 1991;35:143-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic detection of cervical granuloma inguinale. Diagn Cytopathol. 1986;2:138-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Granuloma inguinale of the cervix: a carcinoma look-alike. Genitourin Med. 1990;66:380-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Concomitant malacoplakia and granuloma inguinale of the cervix in acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27:282-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical tuberculosis coexisting with Trichomonas vaginalis. Acta Cytol. 1989;33:945-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pseudotumoral tuberculosis of the uterine cervix.Cytologic presentation. Acta Cytol. 1989;33:305-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytology as an aid in the diagnosis of genital tuberculosis. J Postgrad Med. 1988;34:100-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Female genital coccidioidomycosis (FGC), Addison's disease and sigmoid loop abscess due to Coccidioides immites; case report and review of literature on FGC. Mycopathologia. 1999;145:121-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cokeromyces recurvatus, a mucoraceous zygomycete rarely isolated in clinical laboratories. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:843-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in a postpartum Pap smear. A case report. Acta Cytol. 2001;45:79-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in a liquid-based Papanicolaou test from a pregnant woman: report of a case. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:557-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- The diagnosis of genital bilharziasis by vaginal cytology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1962;83:710-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increased vascularity in cervicovaginal mucosa with Schistosoma haematobium infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1170.

- [Google Scholar]

- Schistosomiasis of the female genital tract: public health aspects. Parasitol Today. 1999;15:378-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of Schistosoma haematobium and human papillomavirus in cervical cancer: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2010;54:205-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Female genital schistosomiasis: case report and review of the literature. South Med J. 2004;97:525-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of genital cervical schistosomiasis: comparison of cytological, histopathological and parasitological examination. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65:233-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Female genital schistosomiasis: a neglected risk factor for the transmission of HIV? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:237.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association between cervical schistosomiasis and cervical cancer: A report of 2 cases. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:995-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case of Taenia saginata (tape worm) infestation of the uterus presenting with abnormal vaginal bleeding. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006;56:377-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pantanowitz L, Michelow P, Khalbuss WE, eds. Cytopathology of infectious diseases. New York: Springer Science; 2011. p. :85-120.

- Response to Article: “Lang TU et al. Molluscum contagiosum of the cervix.”. Diagn Cytopathol 2012 [In Press]

- [Google Scholar]

- Intraoral molluscum contagiosum imitating a squamous-cell carcinoma in an immunocompetent person--case report and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38:802-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molluscum contagiosum: the importance of early diagnosis and treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(3 Suppl):S12-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vegetable cells in Papanicolaou-stained cervical smears. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:45-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vegetable cell contaminants in urinary bladder diversion cytology specimens. Acta Cytol. 2012;56:271-6.

- [Google Scholar]