Translate this page into:

Utility of on-site evaluation of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration specimens

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) is an integral tool in the diagnosis and staging of malignant tumors of the lung. Rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) of fine needle aspiration (FNA) samples has been advocated for as a guide for assessing the accuracy and adequacy of biopsy samples. Although ROSE has proven useful for numerous sites and procedures, few studies have specifically investigated its utility in the assessment of EBUS-TBNA specimens. The intention of this study was to explore the utility of ROSE for EBUS-TBNA specimens.

Materials and Methods:

The pathology files at our institution were searched for all EBUS-TBNA cases performed between January 2010 and June 2010. The data points included number of sites sampled per patient, location of site(s) sampled, on-site evaluation performed, preliminary on-site diagnosis rendered, final cytologic diagnosis, surgical pathology follow-up, cell blocks, and ancillary studies performed.

Results:

A total of 294 EBUS-TBNA specimens were reviewed and included in the study; 264 of 294 (90%) were lymph nodes and 30 of 294 (10%) were lung mass lesions. ROSE was performed for 140 of 294 (48%) specimens. The on-site and final diagnoses were concordant in 104 (74%) and discordant in 36 (26%) cases. Diagnostic specimens were obtained in 132 of 140 (94%) cases with on-site evaluation and 138 of 154 (90%) without on-site evaluation. The final cytologic diagnosis was malignant in 60 of 132 (45%) cases with ROSE and 46 of 138 (33%) cases without ROSE, and the final diagnosis was benign in 57 of 132 (47%) with ROSE and 82 of 138 (59%) without ROSE. A cell block was obtained in 129 of 140 (92%) cases with ROSE and 136 of 154 (88%) cases without ROSE.

Conclusions:

The data demonstrate no remarkable difference in diagnostic yield, the number of sites sampled per patient, or clinical decision making between specimens collected via EBUS-TBNA with or without ROSE. As a result, this study challenges the notion that ROSE is beneficial for the evaluation of EBUS-TBNA specimens.

Keywords

EBUS-TBNA

endobronchial

on-site

ROSE

INTRODUCTION

The evaluation of pulmonary and mediastinal lesions requires thoughtful integration of clinical and radiologic information along with judicious tissue sampling. This multidisciplinary approach facilitates the pathologic diagnosis of benign, reactive, or inflammatory, and malignant disease, as well as appropriate staging as needed. The various modalities of tissue collection have evolved over the years from more invasive approaches, such as mediastinoscopy and open lung biopsy, to the utilization of minimally invasive techniques, including exfoliative cytology, bronchial brushings and washings, and transbronchial or computed tomography-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology. The endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) has proven itself to be a useful tool in the diagnosis, as well as staging, of malignant tumors of the lung and in the assessment of mediastinal lymphadenopathy.[12] The immediate on-site evaluation of EBUS-TBNA samples by a pathologist can serve to guide the clinicians as to the accuracy, as well as the adequacy, of biopsy samples. In addition, the on-site preliminary diagnosis can be helpful in determining the need for either sampling of additional sites for tumor staging or the need to switch to invasive procedures such as mediastinoscopy. Furthermore, on-site evaluation can also be used to triage specimens for ancillary laboratory testing, such as molecular studies, cultures, and flow cytometry. While the advantages of on-site evaluation have been demonstrated for numerous sites and procedures, few studies have specifically investigated its utility in the assessment of EBUS-TBNA specimens.

The intention of this study was to explore the utility of on-site evaluation of EBUS-TBNA specimens; specifically does on-site evaluation improve diagnostic yield of EBUS-TBNA procedures and how it impacts clinical decision making? We sought to address the first question by evaluating a series of end points including specimen adequacy (assessed by nondiagnostic rates, generation of cell block material, and application of immunocytochemical stains and special stains). We queried the latter question by examining the impact of on-site evaluation on the acquisition of surgical pathology biopsy specimens, the number of FNA specimens collected and sites sampled, as well as specimen triaging (flow cytometry). Finally, we evaluated the overall diagnostic accuracy of on-site evaluation in the cohort (as shown by the agreement with the final cytopathologic diagnosis and site-specific surgical pathology follow-up (when available)).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An electronic search was performed using the pathology database at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania to identify all EBUS-TBNA specimens collected from January 2010 to June 2010.

Data from a total of 294 specimens were reviewed, representing material from 149 patients. Pathology reports were retrieved and the following data points were collected: number of sites sampled per patient, location of site(s) sampled, on-site evaluation performed, preliminary on-site diagnosis rendered, final cytologic diagnosis, surgical pathology follow-up, presence of cell blocks, and ancillary studies performed.

The decision as to whether rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) is performed for a given site is determined by the Interventional Pulmonary Department clinicians. Once the clinicians decide to pursue ROSE, cytopathology is contacted and teams consisting of a cytopathology attending, cytopathology fellow, and, in many instances, a resident go on site to evaluate the EBUS-TBNA performed by the clinicians. All EBUS-TBNAs are performed by experienced bronchoscopists with the assistance of trainees. When on-site, the first portion of the specimen expressed from the aspirating needle is split into two slides: one prepared as a Diff-Quik smear (evaluated on-site) and the other which is fixed in 95% alcohol (for Papanicolaou staining). The remaining material present within the needle is rinsed in Normosol® and processed in the laboratory as a ThinPrep®, and if enough material remains, a cell block. The number of passes performed per site is determined by the clinician. As part of on-site evaluation, the attending cytologist assesses adequacy, as defined by site-specific tissue identified or tumor present, as well as renders a preliminary diagnosis.

The preliminary on-site diagnoses were subcategorized into positive for malignancy, indeterminate, and negative for malignancy. Final diagnoses were subcategorized as positive for malignancy, negative for malignancy with granulomas present, indeterminate, and negative for malignancy. The indeterminate category for both the preliminary on-site diagnosis and the final diagnosis included atypical cells present and nondiagnostic specimens. Nondiagnostic specimens included those specimens where inadequate material was recovered and site-specific tissue was not seen (no lymphocytes seen in a specimen called a lymph node). In other words, we used nondiagnostic as the preliminary diagnosis for specimens where ROSE failed to provide adequate on-site material for review. Further, “nondiagnostic” as a final diagnosis was used in cases where additional sampling would be needed to rule out/rule in the presence of malignancy. Specimens characterized as negative for malignancy included those in which site-specific tissue was present, but no malignant cells were noted.

Ancillary studies included immunocytochemical stains, special stains for acid-fast and fungal organisms, and flow cytometry. Molecular testing and acquisition of cultures at our institution is based on clinician request and is not reflexively performed. These data were not reviewed for the current study.

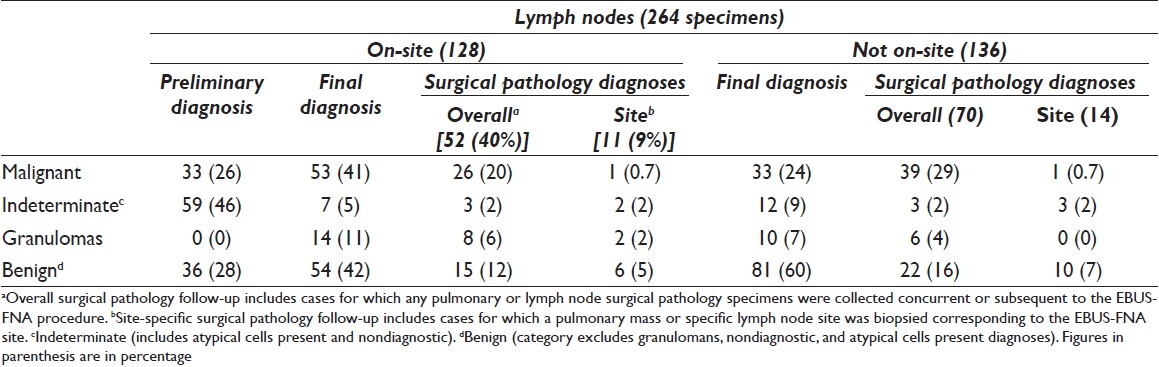

RESULTS

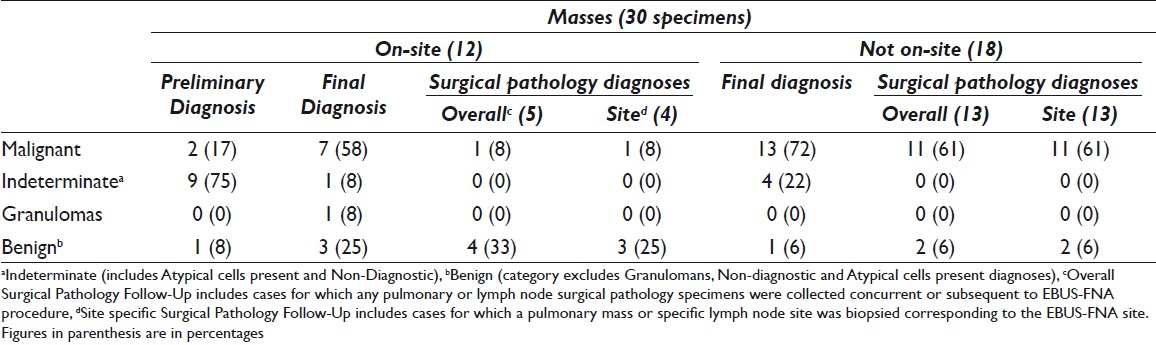

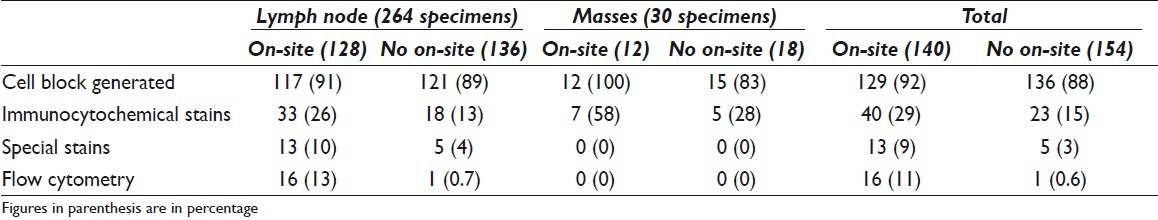

The case cohort included 294 specimens representing 149 patients. Sixty (40%) patients had 1 specimen collected and 89 (60%) patients had more than 1 specimen collected. Of the 294 specimens, 264 (90%) were designated as lymph nodes and 30 (10%) were designated as lung mass lesions. On-site evaluation was requested by the bronchoscopists for 140 of 294 (48%) specimens; of these, 128 (91%) were lymph nodes and 12 (9%) were lung mass lesions [Tables 1 and 2]. On-site evaluation was performed in 40 (67%) patients in whom only one site was sampled as compared with 62 (70%) patients where more than one site was sampled.

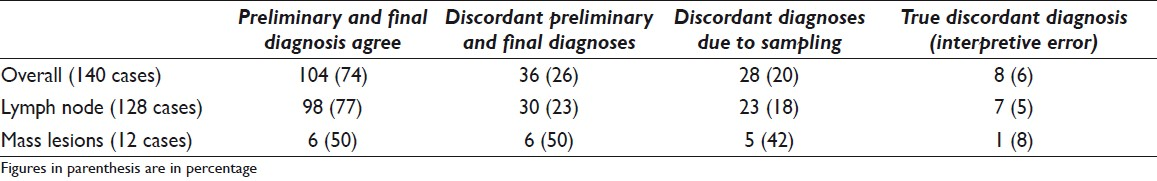

The on-site diagnosis was concordant with the final cytologic diagnosis in 104 (74%) and discordant in 36 (26%) cases. The reasons for disagreement included sampling error in 28 (78%) cases (diagnostic material not seen on-site, but seen on the final preparations (alcohol fixed smear, ThinPrep, and cell block)) and interpretative errors in 8 (22%) cases. The interpretative errors were mainly due to cases diagnosed as “atypical cells” on-site, with a final diagnosis of negative for malignancy in 7 cases, and 1 case interpreted as atypical lymphoid proliferation on preliminary evaluation, with a final diagnosis of malignant epithelial neoplasm [Table 3].

Diagnostic specimens were obtained in 132 of 140 (94%) cases with on-site evaluation and 138 of 154 (90%) without on-site evaluation. The final cytologic diagnosis was malignant in 60 of 132 (45%) cases with on-site evaluation and 46 of 138 (33%) without on-site evaluation [Table 4], whereas a benign diagnosis was rendered in 57 of 132 (47%) with on-site evaluation and 82 of 138 (59%) without on-site evaluation. Granulomas were identified in 25 cases; of these, 15 of 132 (11%) cases had on-site evaluation. The final cytologic diagnosis was indeterminate in 24 cases; of these, on-site evaluation was performed in 8 of 24 (33%) cases [Tables 1 and 2]. A cell block was obtained in 129 of 140 (92%) cases with on-site evaluation and 136 of 154 (88%) cases without on-site evaluation [Table 5].

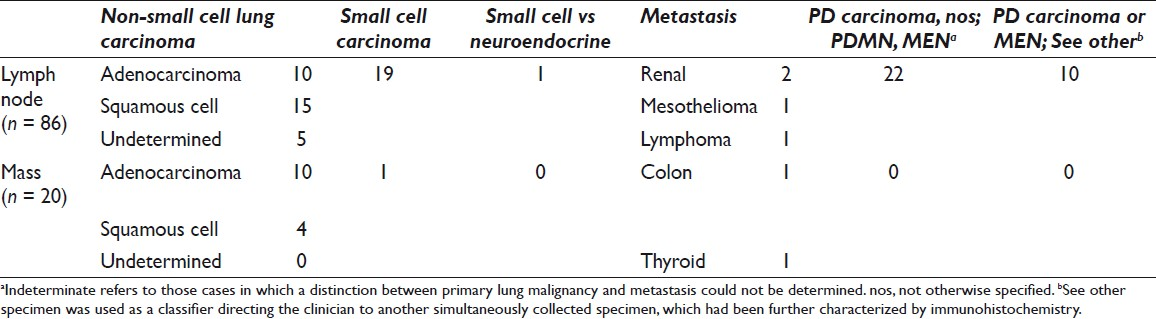

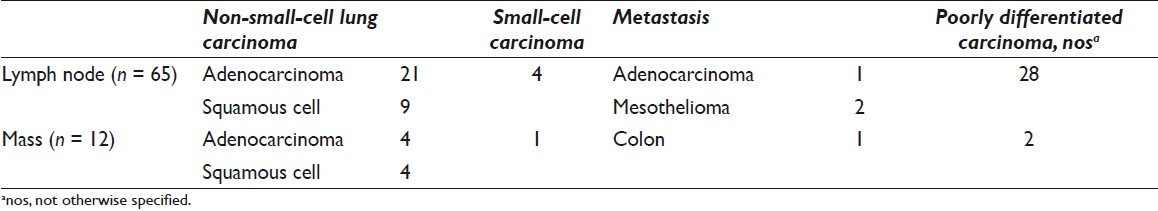

EBUS-TBNAs of lymph nodes were diagnosed as benign (including granulomatous inflammation) in 159 (60%), malignant in 86 (33%), atypical in 16 (6%), and nondiagnostic in 3 (1%) cases [Table 1]. EBUS-TBNAs of lung masses were diagnosed as malignant in 20 (67%), benign in 5 (17%), atypical in 2 (6%), and nondiagnostic in 3 (10%) cases [Table 1]. Of the 106 cases diagnosed as malignant on final cytology, on-site evaluation was performed in 60 (57%) [Table 2].

Ancillary studies recorded included immunocytochemistry, flow cytometry, and special stains. Immunocytochemistry was performed in 63 of 294 (21%) specimens [Table 5]. In all except 1 case, immunostains were performed on unstained cell block slides. Flow cytometry was performed in 17 cases; of these, all except 1 case had on-site evaluation. The one case without on-site evaluation was the only case diagnosed as lymphoma. Special stains for AFB and Grocott were performed on representative specimens from all patients with granulomas identified on the cell block material.

The surgical pathology follow-up was available in 140 of 294 (48%) cases. Malignant diagnosis was rendered in 77 of 140 cases [Table 6]; the diagnoses were adenocarcinoma (25 of 77), squamous cell carcinoma (13 of 77), poorly differentiated carcinoma (30 of 77), small-cell carcinoma (5 of 77), metastatic adenocarcinoma (2 of 77), and mesothelioma (2 of 77). The site-specific surgical pathology follow-up (biopsy material from the same site as EBUS-TBNA) was available in 42 of 140 (31%) cases. Diagnoses were benign (including granulomas) in 23 of 42 (55%), malignant in 14 of 42 (33%), atypical in 3 of 42 (7%), and nondiagnostic in 2 of 42 (5%) cases [Tables 1 and 2].

Lymph node specimens obtained by the EBUS-TBNA with on-site evaluation had surgical pathology follow-up in 52 of 128 (40%) cases and site-specific follow-up in 11 of 128 (9%) cases [Table 1]. Final FNA diagnoses correlated with site-specific surgical pathology follow-up in 9 cases: 8 cases were benign (including granulomas) and 1 was malignant. In the remaining 2 cases, 1 was diagnosed as poorly differentiated carcinoma with squamous differentiation on FNA and the surgical pathology follow-up was diagnosed as atypical. The second case diagnosed as granulomatous inflammation on the FNA was deemed nondiagnostic on surgical pathology.

Surgical pathology follow-up was available in 5 of 30 cases of lung mass with on-site evaluation. Site-specific follow-up was available in 4 cases: 3 were diagnosed as benign and 1 as malignant by cytology. The 3 benign diagnoses rendered by cytology corresponded to 2 cases also diagnosed as benign on surgical pathology and 1 case diagnosed as a neurofibroma by surgical pathology. The 1 case called malignant on cytology was from a specimen showing metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma. The surgical pathology in this case was negative. The case with non-site-specific follow-up was diagnosed as adenocarcinoma on both FNA and surgical pathology.

A malignant diagnosis was rendered during on-site evaluation in 35 specimens [Table 6]. A concomitant surgical biopsy specimen was collected in 10 of 35 (28%) cases; the surgical pathology diagnoses were malignant 8, atypical 1, and benign 1 case. Of specimens where a benign diagnosis was rendered during on-site evaluation, 21 of 37 (57%) specimens had surgical pathology follow-up, 7 of which had site-specific follow-up (all 7 specimens were lymph nodes) [Table 7]. Of the 7 site-specific biopsies performed, 6 were diagnosed on surgical pathology biopsy as benign and 1 was diagnosed as nondiagnostic. Of the remaining 14 cases with non-site-specific surgical pathology follow-up, 10 were diagnosed as benign, 3 were diagnosed as malignant, and 1 was found to be nondiagnostic.

DISCUSSION

During the current era of personalized medicine, the FNA service has become an essential part of clinical management and decision making. A frequently cited reason for on-site evaluation is to procure adequate specimen. A few studies have been published proposing criteria for specimen adequacy indicators; however, to date, no universally endorsed approach exists.[3–5] At our institution, as explained above, specimens are considered adequate if site-specific tissue is identified (lymphocytes for lymph nodes) or lesional tissue is identified. In general, the use of cytologic on-site evaluation has been shown to improve the diagnostic yield of specimen collection for a variety of sites, such as head and neck, pancreas, lung, and the mediastinum.[6–11] Although interpretive pitfalls exist, several studies have shown that the concordance rates for preliminary on-site and final cytologic diagnosis can be similar to those reported for frozen section consultation.[12–16]

Transbronchial needle aspiration biopsy (TBNA) is widely accepted as a relatively minimally invasive, reliable alternative to mediastinoscopy for the diagnosis, and staging of malignant lung and mediastinal lesions. The use of on-site evaluation in conjunction with TBNA has been shown to improve the diagnostic yield of the transbronchial biopsy procedures.[16717] While the use of on-site cytology in the setting of EUS-FNAs of gastrointestinal and mediastinal sites has been extensively investigated and shown to improve diagnostic yield and patient care, to date few studies have specifically addressed the utility of on-site evaluation of EBUS-TBNA specimens.[8–10]

In this study of EBUS-TBNA specimens, 74% of our preliminary and final cytologic diagnoses were concordant while 26% were discordant. The latter were primarily due to sampling error (diagnostic material not seen on-site, but seen on the final preparations (alcohol fixed smears, ThinPrep, and cell block)). There were no false-positive cases. These figures are within the realm of what has been reported in the literature.[317–21] Interestingly, our current study demonstrates no remarkable difference in diagnostic yield between specimens collected via EBUS-TBNA with or without on-site evaluation. Unlike what has been reported for TBNA samples, these findings suggest that on-site evaluation in the setting of EBUS-TBNA may be of no benefit with respect to the acquisition of robust samples.[1722] We believe this may be explained by the employment of ultrasound during EBUS-TBNA procedures, which results in accurate and better sampling of the targeted lesion. Furthermore, our data also suggest that in the setting of suspected sarcoidosis, the on-site evaluation of specimens is unlikely to result in a preliminary diagnosis of granulomatous inflammation as virtually all diagnostic material was identified in cell block material.[23] Nonetheless, with respect to the overall acquisition of diagnostic specimens, we cannot entirely exclude that our results reflect experienced EBUS operators and may not be applicable to other institutions.

Numerous authors have reported the advantages of immediate on-site evaluation of cytology specimens.[24–26] While seemingly intuitive, it has been shown that the presence of on-site cytology assessment can positively impact the diagnostic yield of an interventional procedure translating into a significant savings in health-care dollars and improved patient care.[6] At the same time, it is widely acknowledged that due to current Medicare compensation schedules, cytopathologists are insufficiently compensated for the time spent on-site, rendering this practice model financially problematic for many pathology groups.[6242527] The benefits of direct communication between clinicians and pathologists and the advantage of on-site triage of specimens for ancillary studies are self-evident and frequently commented upon in the literature.[18] Along these lines, we noted that despite roughly equivalent malignant diagnoses, immunohistochemical stains were used more often in cases where on-site assessment was performed (63% vs 37%) and that flow cytometry was requested more often when cytopathology was present on-site (94% vs 6%).

Our finding of an equivalent diagnostic rate between specimens with and without on-site evaluation is an interesting finding. This raises the question of whether on-site assessment improves diagnostic yield in all settings and for all procedure types and whether it is truly universally a cost-saving procedure. In this limited study, we have demonstrated that in the setting of EBUS-TBNA, the presence of on-site cytology services does not impact the rate of diagnostic specimens, nor does it decrease the number of sites sampled per patient. Thus, if the rationale for on-site cytology is to achieve specimen adequacy and to save the patient, and the health care system, additional sampling or a repeat procedure, at our institution, the additional health-care dollars spent for on-site services (88172 and 88177) do not result in added clinical benefit.

The final argument for on-site evaluation of specimens is that a preliminary diagnosis enables the clinician to make prompt management decisions and to acquire additional samples (i.e., surgical pathology biopsies) if needed. While it is true that cases with on-site evaluation are more likely to be triaged for flow cytometric analysis, whether this additional test contributed significantly to the pathologist's ability to render a diagnosis is not immediately clear. As regards specimen adequacy, our data shows that in cases where one might argue that additional material should be collected i.e. cases diagnosed on-site as atypical or nondiagnostic, surgical pathology follow-up was available in only 3 of 68 (4%) cases. Alternatively, in cases where on-site preliminary diagnosis was malignant (35), surgical pathology follow-up was still obtained in 10 of 35 (29%) cases. Similarly, a surgical biopsy was obtained in 21 of 37 (57%) cases with benign on-site interpretation. The rendering of a malignant diagnosis during on-site evaluation should indicate to the clinician that diagnostic material has been obtained and adequacy for ancillary studies has been achieved. If the goal of the EBUS-TBNA is to diagnose and stage a pulmonary malignancy, then by obtaining a positive on-site diagnosis from a specific lymph node station represents adequate tissue sampling. Instead, our data suggest that the clinicians at our institution, despite achieving the stated goal of the procedure, still persist in obtaining additional specimens in the form of surgical biopsies. By the same token, one might expect that an on-site benign diagnosis from a clinically suspicious lymph node may raise concerns of inadequate sampling, leading to additional specimens/passes to ensure accurate staging. This explains the trend toward increased numbers of biopsies in cases where a benign diagnosis was rendered during on-site evaluation. This may also reflect the simple fact that if the procedure is performed for diagnostic and staging purposes while a benign nodal aspirate may stage the patient, an ultimate diagnosis of malignancy can only be achieved by the acquisition of additional tissue.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our limited study demonstrates that at our institution, EBUS-TBNA facilitates the collection of adequate material for pathologic diagnosis and that on-site evaluation does not increase the diagnostic yield of EBUS-TBNA specimens or immediately impact patient care.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that they qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article. Z.B. conceived this study. L.S. and A.G. performed data collection. All authors performed data analysis and interpretation. All authors drafted, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was performed as part of a quality assurance project. All ethical obligations were followed by the authors.

EDITORIAL / PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model(authors are blinded for reviewers and reviewers are blinded for authors)through automatic online system.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2011/8/1/20/90081.

REFERENCES

- Transbronchial needle aspiration in diagnosing and staging lung cancer: how many aspirates are needed? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:377-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration biopsy is useful evaluating mediastinal lymphadenopathy in a cancer center. Cytojournal. 2011;8:10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial fine-needle aspiration: the University of Minnesota experience, with emphasis on usefulness, adequacy assessment, and diagnostic difficulties. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130:434-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspirate (EBUS-TBNA): A proposal for on-site adequacy criteria. Diagn Cytopathol 2010 [In Press]

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytology of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: a retrospective study with histology correlation. Cancer. 2009;117:482-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Utility of rapid on-site evaluation of transbronchial needle aspirates. Respiration. 2005;72:182-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Utility of on-site cytopathology assessment for bronchoscopic evaluation of lung masses and adenopathy. Chest. 2000;117:1186-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Esophageal endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration with an on-site cytopathologist: high accuracy for the diagnosis of mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Chest. 2005;128:3004-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical impact of on-site cytopathology interpretation on endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1289-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration.A cytopathologist's perspective. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:351-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role and accuracy of rapid on-site evaluation of CT-guided fine needle aspiration cytology of lung nodules. Cytopathology. 2011;22:306-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cost/accuracy ratio analysis in breast cancer patients undergoing ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology, sentinel node biopsy, and frozen section of node. World J Surg. 2007;31:1155-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relative accuracy of fine-needle aspiration and frozen section in the diagnosis of lesions of the parotid gland. Head Neck. 2005;27:217-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- An audit study of the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound, fine needle aspiration cytology and frozen section in the evaluation of thyroid malignancies in a tertiary institution. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39:359-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parotid tumors: fine-needle aspiration and/or frozen section. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139:811-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic difficulties and pitfalls in rapid on-site evaluation of endobronchial ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration. Cytojournal. 2010;7:9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid assessment of fine needle aspiration and the final diagnosis--how often and why the diagnoses are changed. Cytojournal. 2006;3:25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intraprocedural evaluation of fine-needle aspiration smears: How good are we? Diagn Cytopathol 2011 [In Press]

- [Google Scholar]

- Endobronchial ultrasound as a diagnostic tool in patients with mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:896-900. discussion 901-2

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic accuracy of samples obtained by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital. Acta Cytol. 2008;52:687-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid on-site evaluation of transbronchial aspirates in the diagnosis of hilar and mediastinal adenopathy: a randomized trial. Chest. 2011;139:395-401.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cell block interpretation is helpful in the diagnosis of granulomas on cytology. Diagn Cytopathol 2011 Jun 21 doi: 101002/dc21761

- [Google Scholar]

- Adequate reimbursement is crucial to support cost-effective rapid on-site cytopathology evaluations. Cytojournal. 2010;7:22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Compensation crisis related to the onsite adequacy evaluation during FNA procedures-Urgent proactive input from cytopathology community is critical to establish appropriate reimbursement for CPT code 88172 (or its new counterpart if introduced in the future) Cytojournal. 2010;7:23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Progression from on-site to point-of-care fine needle aspiration service: Opportunities and challenges. Cytojournal. 2010;7:6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immediate on-site interpretation of fine-needle aspiration smears: a cost and compensation analysis. Cancer. 2001;93:319-22.

- [Google Scholar]