Translate this page into:

Abdominopelvic washings: A comprehensive review

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Intraperitoneal spread may occur with gynecological epithelial neoplasms, as well as with non-gynecological malignancies, which may result in serosal involvement with or without concomitant effusion. Therefore, washings in patients with abdominopelvic tumors represent important specimens for cytologic examination. They are primarily utilized for staging ovarian cancers, although their role has decreased in staging of endometrial and cervical carcinoma. Abdominopelvic washings can be positive in a variety of pathologic conditions, including benign conditions, borderline neoplastic tumors, locally invasive tumors, or distant metastases. In a subset of cases, washings can be diagnostically challenging due to the presence of co-existing benign cells (e.g., mesothelial hyperplasia, endosalpingiosis, or endometriosis), lesions in which there is only minimal atypia (e.g., serous borderline tumors) or scant atypical cells, and the rarity of specific tumor types (e.g., mesothelioma). Ancillary studies including immunocytochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization may be required in difficult cases to resolve the diagnosis. This article provides a comprehensive and contemporary review of abdominopelvic washings in the evaluation of gynecologic and non-gynecologic tumors, including primary peritoneal and mesothelial entities.

Keywords

Abdominopelvic washings

effusion cytology

fluid cytology

pelvic washings

INTRODUCTION

Peritoneal washings were initially described in 1956 for the evaluation of gynecologic malignancies.[1] The purpose of this procedure was to diagnose “early” spread of ovarian cancer. In 1971, Creasman and Rutledge reported the correlation between positive peritoneal washings and prognosis in ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer.[2] Peritoneal washing was subsequently added to the ovarian staging system of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) in 1975.[3] Although peritoneal washing in ovarian cancer staging systems remain part of the FIGO staging system, the role of washings in staging endometrial carcinoma has been controversial and is no longer part of the current FIGO staging system.[45] Furthermore, peritoneal washings are also not included in the staging system of cervical carcinoma, most likely due to low sensitivity in the detection of advanced cervical disease; nevertheless, when such washings are positive they correlate with a very poor prognosis.[67]

The presence of neoplastic cells in peritoneal washings reflects intraperitoneal spread of the neoplastic process beyond the primary organ site. When this occurs, it often correlates with a poor prognosis in a variety of tumors; one important exception is positive washings in patients with borderline ovarian tumors. The prognostic importance of neoplastic cells in washing fluids of patients with gastric cancer has also been recognized[8] and the Japanese Research Society has included this procedure as part of their staging process since 1988.[8] For gastric cancer, a positive peritoneal washing is considered by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as M1 disease;[6] for this reason peritoneal washings are performed during gastric surgery at some institutions.[9] The same concept applies to other gastrointestinal malignancies such as pancreatic cancer.[610]

Since serosal involvement by malignancy (e.g., carcinomatosis) may occur with or without concomitant effusion (e.g., ascites), pelvic washing is an important diagnostic tool. The collection of abdominopelvic (peritoneal) washings (or lavage) and/or related fluid specimens (e.g., cul-de-sac or gutter aspirates) occurs at the time of abdominal surgery, preceding exploratory laparotomy or removal of the primary tumor. Typically sterile saline is instilled (e.g., 50-200 mL) into the abdomen to wash the pelvic and paracolic gutters, as well as the undersurface of both diaphragms. The saline wash from these different sites is then aspirated, pooled, and often mixed with heparin to avoid clot formation. If there is any pre-existing fluid or ascites, the collection of this fluid for submission to cytology should precede the washing procedure.[11]

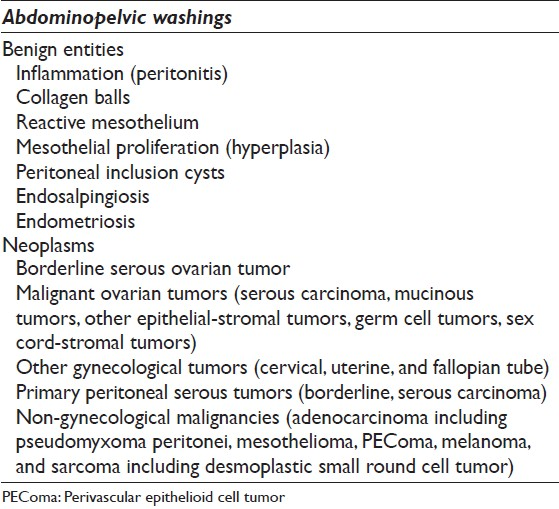

Abdominopelvic washings are challenging specimens to interpret, since they may be positive in benign conditions, borderline neoplastic tumors or malignancies from locally invasive tumors or distant metastases [Table 1]. One of the most helpful approaches in the evaluation of these often challenging specimens is to compare the pelvic washings with the patient's available surgical pathology specimens. This practical approach should be attempted whenever possible to avoid diagnostic errors. Nevertheless, the presence of malignant cells in peritoneal washings is associated with a poor prognosis in the majority of cases. Non-neoplastic findings such as endometriosis, endosalpingiosis, and reactive mesothelial proliferations can be misinterpreted as a malignancy. In general, pelvic washings are rarely used for making a primary diagnosis, but can help document a persistent or recurrent gynecological malignancy with a “second-look” procedure. Such “second-look” peritoneal washings obtained after primary cytoreductive surgery may be difficult to obtain due to adhesions. Also, treatment effect from chemotherapy and/or radiation treatment can alter normal mesothelial cells (e.g., enlargement, anisonucleosis, and prominent nucleoli) which may also mimic malignancy.

This article provides a comprehensive and contemporary review of abdominopelvic washings in the evaluation of gynecologic and non-gynecologic tumors, including primary peritoneal and mesothelial entities.

Normal washings

There are no well-defined criteria for unsatisfactory pelvic washings,[12] but at least a few groups of well-preserved mesothelial cells should be present. The washing procedure traumatically exfoliates mesothelial cells. Specimens with normal findings typically contain benign mesothelial cells that form flat, orderly two-dimensional monolayers of intact stripped sheets of well-spaced polygonal cells with a honeycomb arrangement. Large sheets are often folded or rolled [Figure 1a]. These abraded mesothelial sheets differ from the spontaneously exfoliated three-dimensional (3D) clusters of mesothelial cells characteristically seen in ascites. In cell block sections when sheets of mesothelial cells are transected they may resemble a linear “string of pearls” [Figure 1b]. Rarely, some washing samples can consist of predominantly single mesothelial cells. Benign mesothelial cells are polygonal in shape and have a moderate amount of delicate cytoplasm. They are characterized by uniform, round to oval centrally located nuclei with finely granular chromatin and absent or inconspicuous micronucleoli. In some cases the nuclei can be lobulated, appearing to have grooves, but are infrequently multinucleated.[11] The use of warm saline in some cases may cause mesothelial cells to have a degenerated or “washed out” appearance. Degenerated mesothelial cells can have paranuclear vacuoles that can indent the adjacent nucleus.

- Normal mesothelium in pelvic washings. (Left) This washing shows a large, intact, folded sheet of evenly spaced mesothelium (Pap stain, ×200). (Right) Normal mesothelium is shown arranged as a “string of pearls” in a cell block preparation (H and E, ×200)

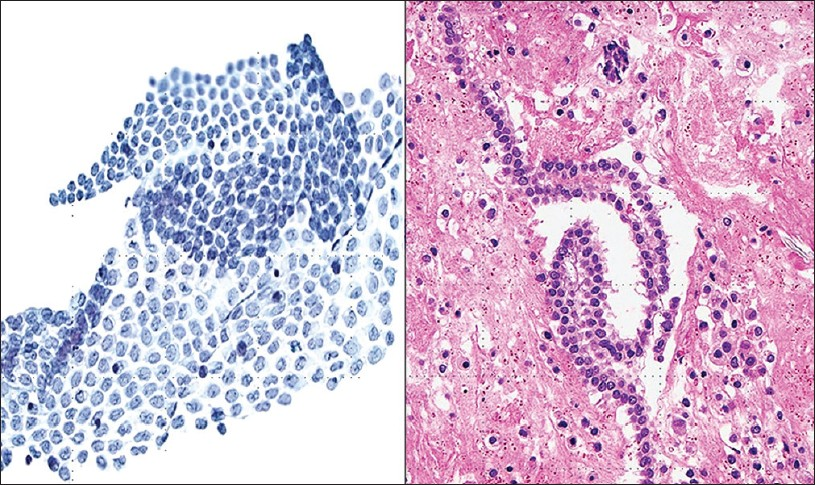

A variety of pathologic conditions can cause reactive changes in mesothelial cells, ranging from pelvic masses, endometriosis, to systemic conditions such as uremia or liver disease. Reactive mesothelial cells [Figure 2] demonstrate a greater spectrum of cellular cytologic changes. Reactive mesothelial cells are more often arranged in large clusters, balls, or non-branching papillae. These cells tend to be plumper with dense cytoplasm and vacuoles when compared to normal mesothelial cells. Nuclear enlargement is also frequently present, resulting in slightly higher nuclear to cytoplasmic (N/C) ratios. Nucleoli may be small to prominent, binucleation and multinucleation can be seen, as well as mitotic figures. In such cases it is expected that there will be associated inflammatory cells present.[111213] Reactive mesothelial change needs to be distinguished from more exuberant reactive mesothelial hyperplasia, multilocular peritoneal inclusion cyst (MPIC), atypical mesothelial proliferation, and neoplastic conditions such as adenocarcinoma and mesothelioma. Features that can help distinguish reactive mesothelial cells from malignancy include the lack of a foreign population and the presence of a spectrum of changes from benign to reactive. Complex papillary or branching clusters should not be present. Reactive mesothelial cells usually maintain their organized structure with well-spaced cellular arrangements. Features of mesothelial differentiation such as polygonal or round shapes, biphasic staining cytoplasm and well defined cellular borders with windows between cells can be helpful to exclude metastatic disease.[11121314]

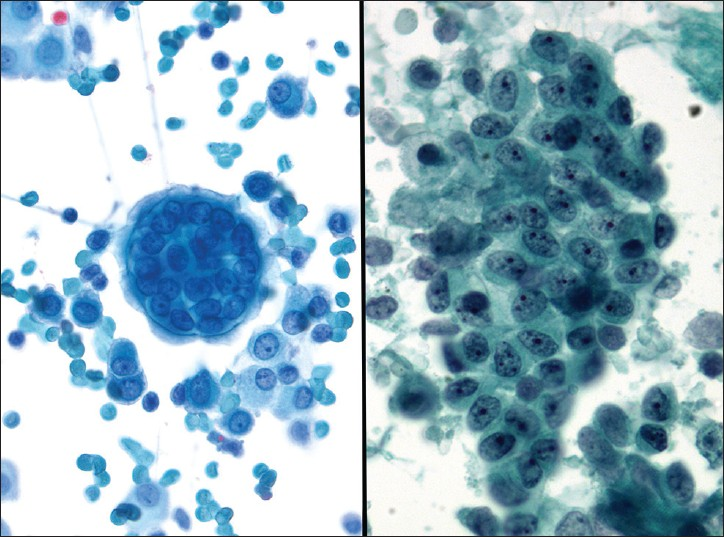

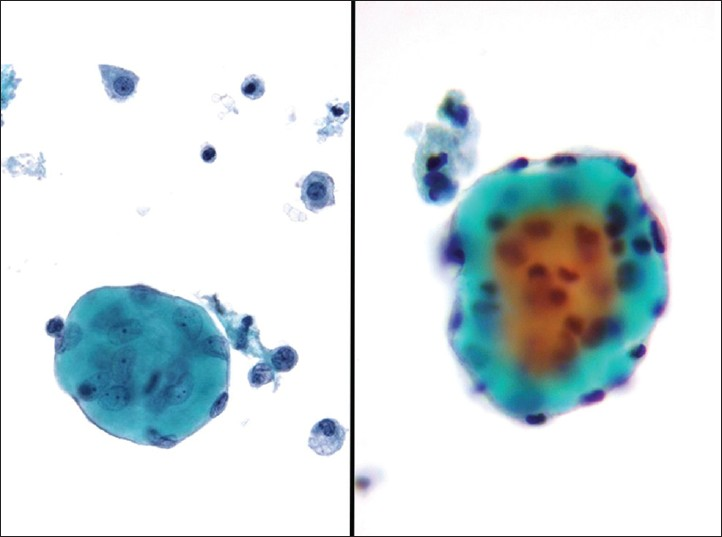

Normal washings may also contain other structures the cytopathologist should be aware of. Collagen balls, for example, can be observed in 4.5% to 48% of peritoneal washings [Figure 3].[1516] They represent spherical or oval structures containing dense central matrix material on Pap stained slides, surrounded by a single layer of small round uniform cells. The name “collagen,” therefore, is a misnomer. These balls are surrounded by a single layer of bland mesothelial cells. They are not typically seen in spontaneous effusions. They are not of clinical importance, and are possibly derived from the adenofibromatous ovarian surface. Nevertheless, when they are present the differential diagnosis includes benign mesothelial lesions, well differentiated papillary mesothelioma (WDPM), diffuse malignant mesothelioma as well as clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Also, collagen balls should not be mistaken for psammoma bodies or metastatic adenocarcinoma. Depending on the surgical procedure performed, some washing can be very bloody and can contain small fragments of the abdominal wall skin, adipose tissue or skeletal muscle tissue. Lysed adhesions may present with vascular (capillary) tangles in peritoneal washings.[11] Finally, ciliocytophthoria or detached ciliary tufts in peritoneal fluid is not an uncommon finding, especially in pelvic washings of females in the second half of the menstrual cycle [Figure 4]. The first description of these structures has been ascribed to Hans-Joachin Ebner in respiratory samples of patients with asthma.[17] However, Papanicolaou cleverly named these detached ciliary tufts as ciliocytophtoria (destruction of the cilia).[12] They are remnants of ciliated epithelium, occurring secondary to fluid contamination from ciliated tubal epithelium or endosalpingiosis. They are anucleated cell fragments composed of cilia and a small portion of cytoplasm, and may be confused with ciliated or flagellated protozoa.

- Reactive mesothelium. These clusters contain plump mesothelial cells with small nucleoli (Pap stain, ×600)

- Collagen balls. These balls contain central dense, pale green matrix material lined by attenuated bland mesothelial cells (Pap stain, ×400)

- Ciliocytophthoria. Circles show detached acellular ciliary tufts in this case of endosalpingiosis (Pap stain, ×400)

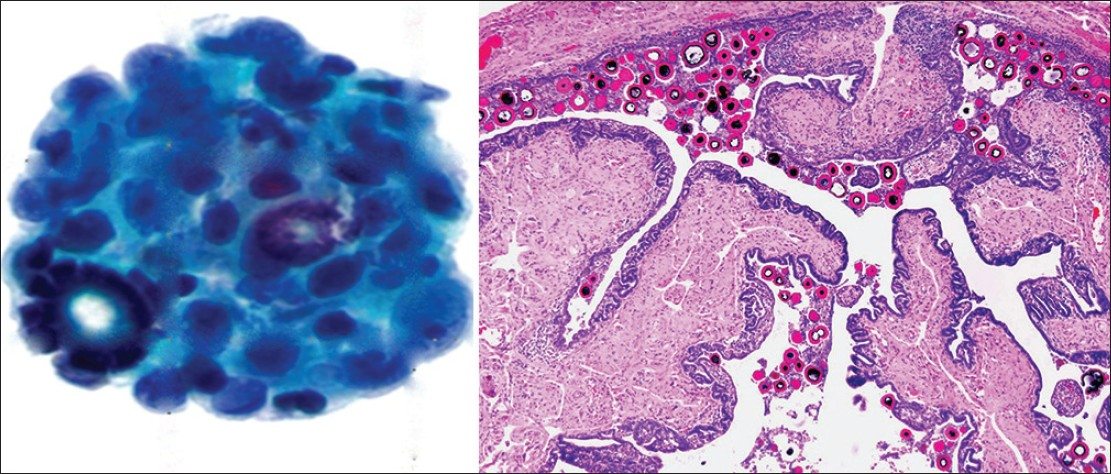

Psammoma bodies

Psammoma bodies are calcifications arranged in concentric laminations to form a spherical structure [Figure 5]. These structures appear purple on Pap stain, which is a helpful feature to distinguish them from collagenous balls which stain more green in color. In some cases they appear to have fragmented or cracked edges. They are seen in approximately 15-20% of peritoneal fluid specimens, and can be associated with non-neoplastic as well as benign and malignant neoplastic processes.[12] Some of the most common benign processes are: Mesothelial hyperplasia, endosalpingiosis, ovarian cystoadenoma and adenofibroma. The most common associated malignancy is papillary serous ovarian carcinoma, although these bodies can be infrequently also encountered with endometrioid carcinoma. Other non-gynecologic papillary carcinomas (e.g., thyroid, kidney, lung and rarely mesothelioma) can also be associated with psammoma bodies. An abundance of psammoma bodies may be indicative of psammocarcinoma. Psammocarcinoma is a rare variant of low grade serous carcinoma of the gynecologic tract and peritoneum associated with a favorable prognosis. It is characterized histologically by infiltrative low-grade serous carcinoma with innumerable psammomatous calcifications (associated with ≥75% of epithelial cell nests) [Figure 6].[18] Cytologic findings include low grade epithelial atypia in papillary cell groups accompanied by numerous psammoma bodies. Sometimes over 80 variably sized bodies per cytologic slide or cell block section can be seen. In psammocarcinoma the tumor cells have high N/C ratios, irregular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and variable hyperchromasia.[19]

- Psammoma bodies. (Left) Psammoma bodies are shown associated with a low grade serous carcinoma. There is atypia with overlapping pleomorphic epithelial cells in this cell cluster (Pap stain, ×400). (Right) A benign fallopian tube with multiple intratubal psammoma bodies is shown (H and E, ×200), a common source of benign psammoma bodies

- Psammocarcinoma. (Left) The cell block from this pelvic washing shows abundant psammomatous calcifications of varying size associated with clusters of atypical epithelial cell groups (H and E, ×200). (Right) The tumor resection shows that over 75% of the tumor cell nests in this case were associated with calcifications (H and E, ×200)

Endosalpingiosis

Endosalpingiosis refers to the presence of ectopic benign glands lined by tubal-type epithelium. Endosalpingiosis is usually multicentric and can involve the peritoneum as well as other pelvic structures, including the ovarian surface and paratubal tissue, as well as pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes. It occurs mainly in females of reproductive age. Although endosalpingiosis is typically an incidental finding and only rarely manifests as a cystic lesion, it is a potential pitfall for false positive washings.[1120] Cytology samples involved by endosalpingiosis are often of low cellularity, and show cohesive aggregates and/or non-branching papillae or clusters of small, uniform cuboidal to columnar cells with scant basophilic cytoplasm, the nuclei display regular nuclear membranes, fine chromatin and small nucleoli. The epithelium in lesions of endosalpingiosis can be ciliated or non-ciliated, and unlike malignancy is mitotically inactive. In general, the finding of cilia supports a benign diagnosis.[11121620] However, rare ciliated variants of carcinoma of the female genital tract have been described.[212223] It is important to remember that endosalpingiosis is positive for B72.3 and also shows nuclear estrogen receptor (ER) and progesteron receptor (PR) positivity. Paired box-8 (PAX8) is helpful to confirm the Müllerian origin of these cells.[24] Mucin production in these cells may rarely be seen. Psammoma bodies are also commonly associated with these glands. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages, typical of endometriosis, are not usually present. The differential diagnosis includes reactive mesothelium, endometriosis and serous neoplasia. The presence of a complex branching architecture, single atypical cells, mitotic activity, nuclear atypia, and prominent nucleoli favors a neoplastic process.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is the ectopic presence of endometrial tissue (glands and stroma) outside the endometrium and myometrium, and when seen is likely due to rupture of an endometriotic cyst. This rare, benign condition may be seen in up to 10-15% of women of reproductive age. Patients are often symptomatic (e.g., pelvic pain, dyspareunia, infertility), may present with complications (e.g., ovarian or intestinal endometriosis, ascites, adhesions, hemoperitoneum from ruptured bloody cysts), and have an elevated cancer antigen-125 (CA-125). They often have identifiable tender cystic intra-abdominopelvic nodules. A definitive diagnosis requires documenting the presence of endometrial epithelial cells, endometrial stromal cells and/or hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Endometrial cells in washings tend to be small to medium sized ovoid to columnar cells with bland nuclei. These cells may be arranged in sheets or tight balls with a honeycomb pattern, and occasionally one may even find branching tubules. Mild atypia, mainly in the form of distinct nucleoli, can be observed and result in a false positive diagnosis of malignancy, especially if the other components (stromal cells and hemosiderin-laden macrophages) are inconspicuous [Figure 7].[11121625] Endometrial stromal cells are usually not identified in washings, but when present, they have a histiocytic or spindle cell appearance. When stromal cells are decidualized, they will have more cytoplasm and round to oval nuclei. CD10 positive immunostaining can help demonstrate the presence of an endometrial stromal component.[26] Hemosiderin-laden macrophages and hemolyzed blood are usually present in the background. In fact, macrophages are often the predominant finding. The presence of old hemolyzed blood helps to distinguish this from surgical bleeding which contains mainly intact red blood cells. The finding of hemosiderin-laden macrophages alone is non-specific, as they may be seen in any condition associated with intraperitoneal bleeding. Moreover, there may be psammoma bodies present in these cases, and commonly reactive mesothelial cells are also seen. The differential diagnosis of endometriosis includes benign hemorrhagic cystic lesions, metastatic endometrial adenocarcinoma, and low grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. The latter two conditions are characterized by having greater atypia and mitotic activity. Misleading features that may be seen with endometriosis are decidual change, eosinophilic metaplasia and mucinous metaplasia.[27]

- Endometriosis. (Left) This washing contained loose clusters of benign endometrial cells. These cells are of uniform size, small and lack nucleoli. Note also the presence of a few hemosiderin-laden macrophages (Pap stains, ×400). (Right) In this case of endometriosis the washing shows predominantly hemosiderin-laden macrophages associated with old hemolyzed blood (H and E, cell block, ×200)

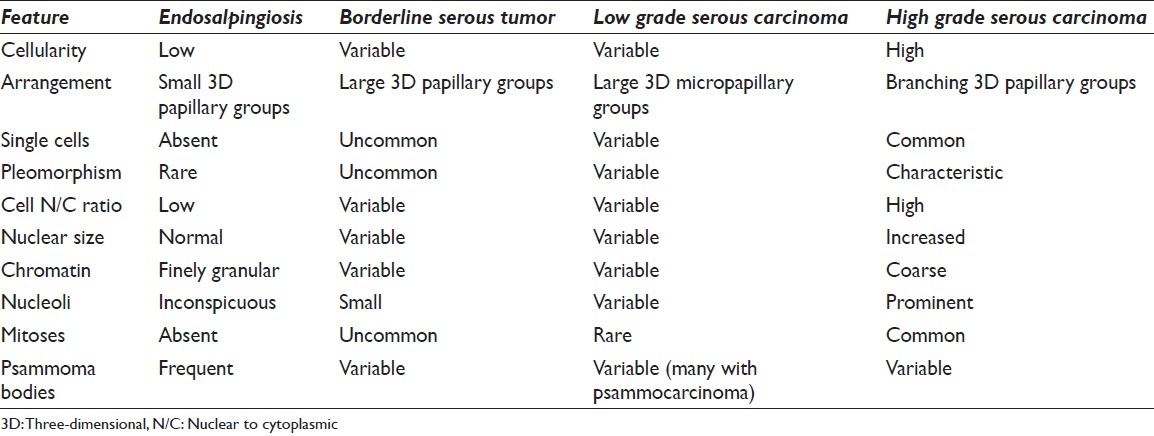

Serous tumors of the ovary

Most serous tumors (serous cystadenoma and adenofibroma) of the ovary are benign. The remainder are serous carcinomas, and less often serous borderline tumors (SBTs) or ovarian serous neoplasms of low malignant potential. SBT is a distinctive tumor with histologic features intermediate between serous cystadenoma and serous carcinoma. SBT is characterized by epithelial proliferation and tufting, but differentiated from serous carcinoma by the absence of ovarian stromal invasion. SBT accounts for 10-20% of all epithelial ovarian tumors. It can occur at any age, but is mainly seen in women of reproductive age. This tumor is bilateral in approximately one-third of cases, and extra-ovarian spread in the form of peritoneal implants is seen in approximately 35% of cases. Patients with invasive peritoneal implants have a worse prognosis.[2829]

The sensitivity of peritoneal washing as an indicator of peritoneal implants in the literature varies from 69% to 90%.[303132] Approximately 30-40% of SBT are associated with positive pelvic washings.[31] Nevertheless, some studies have reported negative cytology in the presence of disseminated peritoneal disease in 20-85% of cases.[303132] Positive pelvic washings are highly indicative of surface ovarian involvement or peritoneal implants. There are no cytologic features that alone can distinguish invasive from non-invasive serous implants.[303132] Conversely, 16-23% of patients with a positive washing have negative staging biopsies. These discrepancies may be explained by sampling issues or the presence of benign mimics such as endosalpingiosis.

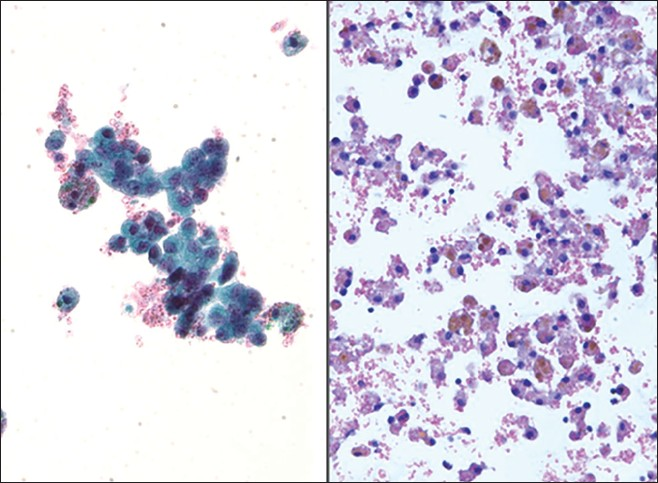

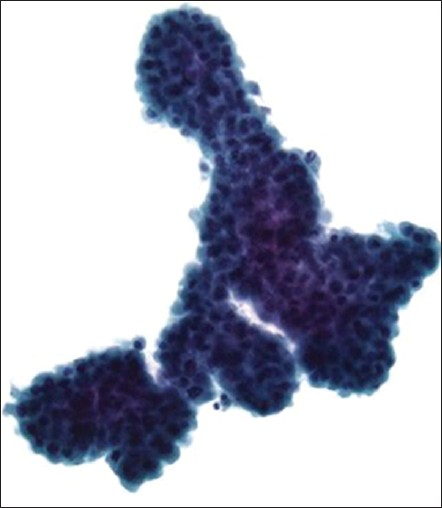

Pelvic washings involved by ovarian SBT display variable cellularity and a two-cell population composed of mesothelial and epithelial cells [Figure 8]. Positive cases usually demonstrate large papillary clusters of slightly atypical glandular cells with smooth borders and relatively few single cells. The tumor cells tend to be small, with well-defined borders and have basophilic cytoplasm. A nucleus is usually monomorphic with coarse chromatin and high N/C ratios. In some cases cytoplasmic vacuolization and ciliated cells may be seen. However, in SBT there is mild or even absent nuclear atypia and mitoses are infrequent. Psammoma bodies are often present.[25333435] The authors believe that the presence of tumor cells in washings from a patient with SBT should be interpreted as positive for serous neoplasm (or low grade serous neoplasm), and not reported out as positive for serous carcinoma. Therefore, if possible it is best to correlate the cytology findings in these cases with the histopathology in the corresponding oophorectomy specimen. The differential diagnosis includes benign entities such as mesothelial hyperplasia and endosalpingiosis, as well as frank serous carcinoma [Table 2].

- Ovarian serous borderline tumor (SBT). (Left) A papillary group of serous borderline tumor cells with minimal nuclear atypia is shown among many single vacuolated macrophages and reactive mesothelial cells (Pap stain, ×400). (Upper right) A psammoma body is associated with this group of tumor cells, arrow (Pap stain, ×400). (Lower right) Cell block showing a papilla with a stromal core lined by a simple layer of serous tumor cells with mild cytologic atypia (H and E, ×400)

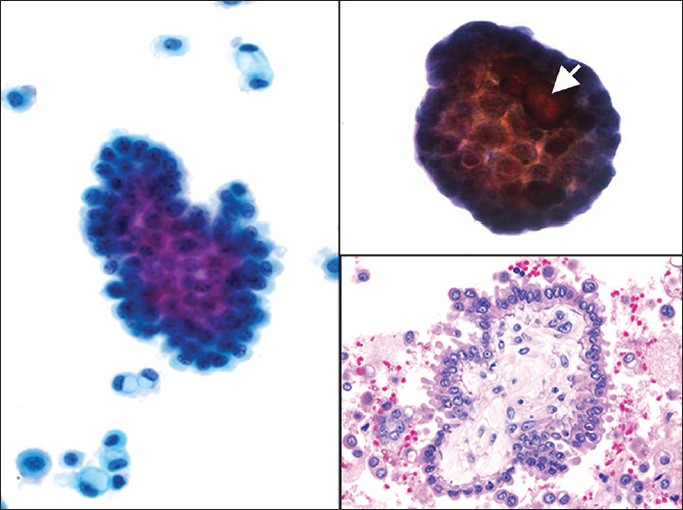

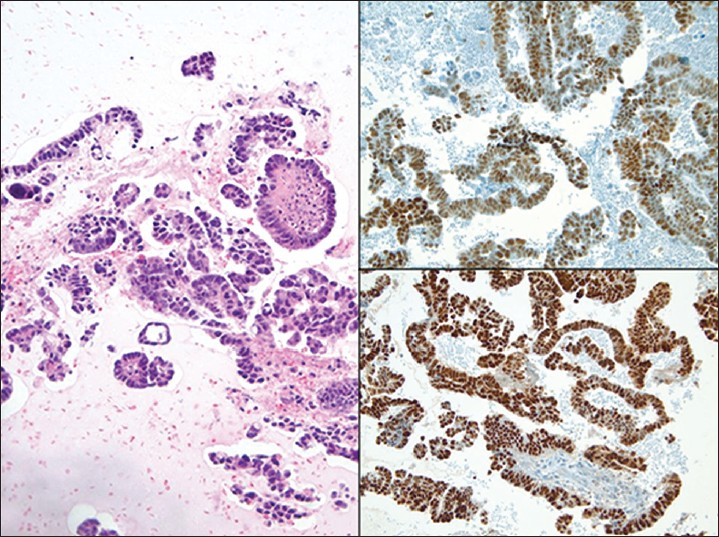

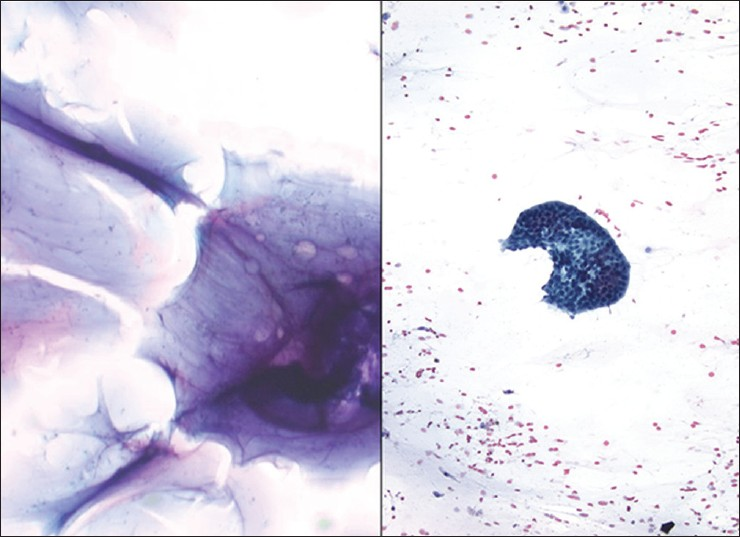

Serous carcinoma is the most common primary ovarian epithelial malignancy, and typically presents in women 50-60 years of age. Although traditionally these carcinomas have been treated as one disease, it has been accepted in the literature that they perhaps represent a heterogeneous group of neoplasms with different pathogenesis, morphological features and prognosis.[363738] Although there are several grading systems, the two-tier grading system described by Malpica et al., has been well accepted due to good reproducibility and its correlation with prognosis.[39] In this grading system, serous carcinomas can be of low or (more commonly) high-grade. The distinction is made by the presence of mitoses and atypia. High-grade tumors have more than 12 mitoses/10 high power fields and marked cytological atypia, defined by more than three time variation in nuclear size.[39] Low grade serous carcinomas are indolent tumors, and mutations of Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS) and vRaf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1BRAF can be found in the majority of these tumors.[363738] Histologically, some tumors may have a micropapillary pattern or it may be associated with numerous psammoma bodies (so-called psammocarcinoma, as described before). Most patients present with clinical findings such as an ovarian mass, abdominal swelling, or metastases. Typically, washings in these cases are cellular with well-formed 3D papillary fragments [Figure 9]. The large papillae often have distinct fibrovascular cores. Single, large atypical cells are not commonly present. The neoplastic cells are monotonous, with small hyperchromatic nuclei and multiple nucleoli. Peripheral palisading of nuclei may occur in low-grade tumors. Low grade serous carcinoma is very difficult to differentiate from SBTs. In addition, it has been postulated that well differentiated serous carcinoma arises in a stepwise progression from cystadenoma or adenofibroma to SBT and finally to low grade carcinoma. The evidence supporting this model includes the fact that borderline tumors are usually seen in association with low-grade serous carcinoma in approximately two-thirds of the cases, and that both tumors frequently show the same genetic mutations.[363738] Micropapillary serous carcinoma has been described in peritoneal washings as small well-formed papillary structures composed of small, monotonous, orderly distributed cells that have hyperchromatic nuclei and multiple nucleoli. Only rare cases demonstrate well-formed papillary structures with fibrovascular cores.[40]

- Ovarian serous carcinoma in a pelvic washing. (Left) This positive washing has many papillary groups of tumor cells (H and E, ×200). (Right) This cell block shows sections of papillary fragments comprised of atypical pleomorphic epithelial tumor cells (irregular nuclear contours, open chromatin and macronucleoli) and associated psammoma bodies (H and E, ×400)

High grade serous carcinomas are aggressive tumors. Histologically, these tumors can have a diverse morphologic appearance ranging from solid to papillary tumors. However, the classic morphological description is a complex papillary architecture with hierarchical branching, slit-like spaces and intermediate to high nuclear grade. At the molecular level, these tumors demonstrate chromosomal instability and tumor protein 53(TP53) mutations.[36373839] Peritoneal washings tend to be highly cellular, have larger tissue fragments (sometimes with over 30 cells) with complex architecture, crowded and disorganized cell arrangements, marked nuclear atypia, pleomorphism, macronucleoli and mitoses when compared with low grade serous tumors. Isolated large tumor cells with eccentrically placed atypical nuclei or multinucleation are also common findings.[14354041] Most serous carcinomas are immunoreactive for Wilm's tumor 1 (WT1), CA-125 and PAX8 [Figure 10]. In some cases they may also stain with cytokeratin 5/6 (CK5/6) and D2-40. Higher grade carcinomas are more likely to be positive for p53 and p16.[42434445] The differential diagnosis includes SBTs, other gynecological neoplasms (e.g., endometrioid adenocarcinoma), and metastases (e.g., breast carcinoma). The distinction of low grade serous tumors from high grade serous carcinoma is based on cytomorphologic features. For example, a recent study using p53 immunostaining on pelvic washings concluded that although the expression of p53 parallels with the severity of tumor grade, it does not improve the sensitivity when compared with classic cytomorphology.[46]

- Ovarian high grade serous carcinoma in a pelvic washing. (Left) The cell block shows fragments of serous papillary carcinoma (H and E, ×200). The tumor cells in this case demonstrate positive nuclear immunoreactivity for p53 (Upper right) and PAX8 (Lower right)

Primary peritoneal serous tumors

Most primary Müllerian tumors of the peritoneum are serous in nature. The peritoneum may harbor serous lesions that are non-neoplastic such as endometriosis to those that are neoplastic, which are morphologically identical to their ovarian counterparts and associated peritoneal implants. The diagnosis of a primary peritoneal serous neoplasm has been defined by the Gynecologic Oncologic Group.[47] Briefly, the diagnosis depends on (i) the presence of either normal ovaries or ovaries showing only minimal surface involvement, (ii) tumor involvement at the extra-ovarian sites must be greater than that of the surface of either ovary, (iii) the tumor should have serous morphologic features and (iv) the patient must not show evidence of other primary cancers that may explain peritoneal involvement. Since the first description of primary peritoneal serous carcinoma by Swerdlow in 1959 under the title of “mesothelioma of the pelvic peritoneum resembling papillary cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary,”[48] this entity has been found to be more common than previously thought. There are three main theories regarding the origin of pelvic serous carcinoma; they are thought to arise either from ovarian surface epithelium or Müllerian inclusions, or Müllerian epithelium located elsewhere in the peritoneal cavity, of from the fallopian tube epithelium.[49] In recent years attention of this theory focused on the fallopian tube as the source of precursor lesions.[505152] With that possibility in mind, Landon et al., studied the utility of peritoneal washing for detecting occult primary peritoneal carcinoma in 117 patients with breast cancer 1 (BRCA-1 or BRCA2 mutations. They found that washings were positive in less than 1% of their patients.[53] The authors recommended caution in interpreting these samples due to various potential pitfalls that can lead to erroneous diagnoses.[53] Of their five patients with true serous lesions on surgical specimens, four had a benign peritoneal washing interpretation.

Primary peritoneal SBTs were previously called atypical endosalpingiosis, primary papillary peritoneal neoplasia, and peritoneal serous micropapillomatosis of low malignant potential. These borderline tumors manifest as diffuse, miliary granules or small nodules on the peritoneal and omental surfaces. Rarely, they may form cysts, larger plaques or tumor masses. Tumor cells of borderline tumors show no invasion into the submesothelial layers of the peritoneum or omentum. The cytomorphology of serous tumors is similar to that described for ovarian cases. The differential diagnosis between a primary serous carcinoma and a diffuse malignant mesothelioma can be difficult. Ancillary studies, immunocytochemistry and even electron microscopy may be required to resolve the diagnosis. Calretinin as a mesothelial marker and BerEP4, MOC31 and ER to support epithelial origin are useful markers.[445455] Other primary Müllerian tumors of the peritoneum such as malignant mixed mullerian tumors (MMMT) are extremely rare.[5657] TP53 mutations have been reported in these tumors, which is only rarely seen in uterine or ovarian MMMT.[56] A final entity to consider is ectopic decidua associated with pregnancy. The cytoplasm in cases with decidua can have bright pink or orange cytoplasm resembling cytoplasmic keratinization.[58]

Ovarian mucinous tumors

Mucinous neoplasms account for a smaller proportion of ovarian tumors. Although traditionally mucinous adenocarcinoma has been considered the second most common epithelial malignancy of the ovary, it has been reported by Seidman et al., in a large study of consecutive cases from a single institution as having an incidence of 3%.[59] Ovarian mucinous tumors tend to be the largest of all ovarian tumors, and therefore will frequently traumatize the nearby mesothelial lining. They occur with increased frequency in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Most of these tumors are benign (e.g., mucinous cystadenoma), some are borderline, and only a few are actual carcinomas. Such tumors may be of endocervical (so-called Müllerian) or intestinal type, both of which have epithelial cells with intracellular mucin. Positive pelvic washings usually show groups of tumor cells with mucin differentiation, and can also have background extracellular mucin. The differential diagnosis includes germ cell tumors and extra-genital metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma (e.g., appendix, colon, and pancreas). Immunostains such as ER, PR and CK7 are positive in ovarian tumors compared to CK20 and caudal type homebox protein-2 (CDX2) positivity seen in colorectal adenocarcinoma. It is important to mention that mucinous ovarian tumors of intestinal type often have immunohistochemical profiles similar to colon cancer; they can express focal or diffuse enteric markers such as CK20, CDX2, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), villin, and CA-19, are ER negative, and harbor KRAS mutations.[42606162] The immunohistochemical profile of primary mucinous ovarian tumors can also overlap with that of pancreticobiliary tumors. Deleted in pancretic cancer (DPC4) or SMAD4 can be a helpful immunostain, since it is positive in ovarian mucinous tumors and negative in approximately 50% of pancreatic tumors.

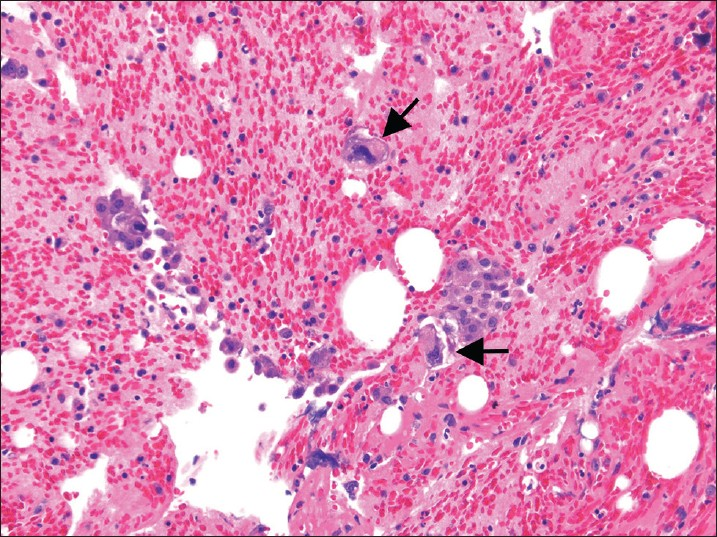

Other ovarian tumors

A variety of other surface epithelial-stromal tumors is encountered in the ovary including endometrioid epithelial tumors, clear cell tumors, undifferentiated carcinoma, MMMT, adenosarcoma, endometrioid stromal sarcoma and other rare tumors (e.g., small cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, hepatoid carcinoma). Positive pelvic washings in these cases usually resemble their histopathological tumor counterpart [Figure 11]. Both neoplastic epithelial and sarcomatous components, as well as heterologous elements, can be present in a MMMT [Figure 12]. However, the sarcomatous elements are often scarce in washings. Clear cell adenocarcinoma is a high grade gynecologic malignancy with distinctive histologic features. Microscopically, clear cell adenocarcinoma is characterized by the presence of hyaline cores of papillary clusters surrounded by hobnail clear cells, so called “raspberry bodies”.[63] These raspberry bodies could be seen in fluid specimens as well as in fine needle aspiration (FNA) and scrape samples.[64] The tigroid background, a feature described with FNA cytology of these tumors, is not frequently present in fluids.[65] The hepatocyte nuclear factor 1-alfa (HNF1-alpha) stain is helpful in differentiating clear cell carcinoma of the ovary from high-grade serous carcinoma, given that both will show high-grade nuclear features.

- Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary in a pelvic washing. (Left) Many polyhedral clear tumor cells with pale vacuolated cytoplasm are shown in this washing (Pap stain, high magnification). (Upper right) The tumor cells in this cell block have abundant cytoplasm and eccentric atypical nuclei. Note the hyaline cytoplasmic inclusion in one of these tumor cells (H and E, ×400). The ooophorectomy specimen demonstrates a papillary pattern that may mimic serous tumors and renal cell carcinoma. The papillary cores in this tumor characteristically demonstrate some hyalinization (H and E, ×200)

- Malignant mixed mullerian tumors in a pelvic washing cell block. This bloody fluid contains a few clusters of carcinoma cells associated with larger, scattered sarcoma tumor cells with markedly pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei (H and E, ×200). Arrow showing markedly pleomorphic cells

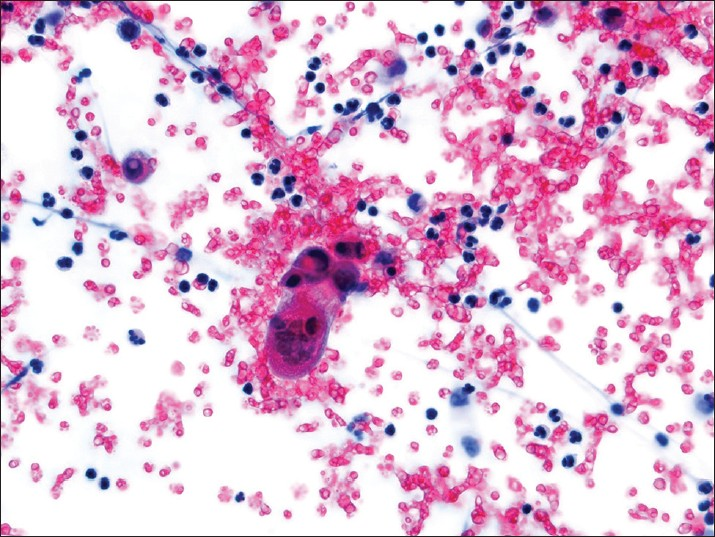

Germ cell tumors of the ovary can be benign or malignant, and many occur in children and young adults. Positive pelvic washings in these cases usually also resemble their histopathologic tumor counterpart. The most common germ cell tumor of the ovary is a teratoma (dermoid cyst). Keratin from ruptured dermoid cysts in the abdominal cavity can elicit an exuberant host granulomatous response. Cases of immature teratoma have been reported in effusions. The neoplastic cells have been described as immature neuroepithelial cells forming rosette like structures, keratinized squamous cells, and glial appearing cells present in a reactive mesothelial cell background.[6667] Immunohistochemical stains for glial associated fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) can be helpful in highlighting glial tissue. Curiously, cases of ependymomas associated with ovarian teratomas have been reported as well as primary peritoneal ependymomas. The peritoneal washing in such cases often demonstrate a population of many isolated spindle and stellate cells, sometimes forming true rosettes. These tumor cells usually display abundant fibrillary cytoplasmic processes. Numerous papillary clusters associated with psammoma bodies can be present, as well as cilia.[6869] In cases of metastatic choriocarcinoma one can identify trophoblasts in a bloody washing [Figure 13]. However, syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells can also occur in other ovarian germ cell tumors. Another potential cause for the presence of cytotrophoblast and syncitiotrophoblasts in pelvic washings is chronic ovarian pregnancy.[70] Yolk sac tumors are described in fluids as having moderate to highly cellular smears, with several cohesive 3D clusters with smooth borders and an occasional papillary configuration. Many cells have vacuolated cytoplasm and eccentric placed hyperchromatic nuclei with marked pleomorphism and inconspicuous nucleoli.[71] The cytomorphologic features of yolk sac tumors in fluid cytology overlap with adenocarcinoma and the use of a cell block for a definitive diagnosis is recommended.[72] Immunostains in challenging cases is usually necessary. Dysgerminomas or seminomas are positive for CD117 (c-kit), placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP), and octamer-binding transcripion factor 3/4 (OCT3/4) (nuclear staining), yolk sac tumors are positive for alpha-fetoprotein AFP and glypican-3, embryonal carcinomas are positive for CD30, and syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells for human chorionic gonadotropin HCG.

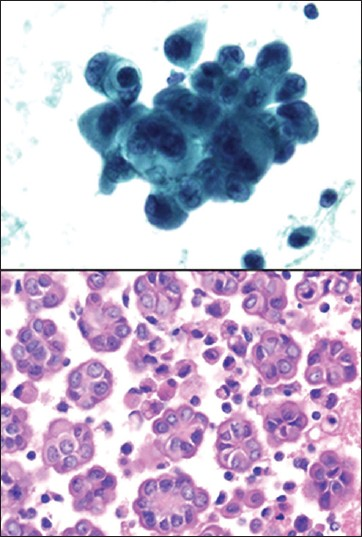

Sex cord-stromal tumors account for only a small proportion of primary ovarian tumors. These include granulosa cell tumors (adult and juvenile tumors), fibroma-thecoma tumors and sertoli-stromal cell tumors, among others. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor cells have been described as tightly packed, molded cells with high N/C ratios and rare cytoplasmic clearing.[72] A variant of this tumor, the so called ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor with retiform pattern, has been reported to present in fluid with tissue fragments resembling ball-like arrangements similar to collagen balls.[73] Granulosa cells in peritoneal washings have scant cytoplasm and uniform oval to angulated nuclei with grooves [Figure 14]. Call-Exner bodies in fluid are uncommon.[7475] The Call-Exner bodies in fluid appear as small clusters of cells in a rosette pattern with a central hyaline globule that stains green or blue on Pap stain or pink on Diff-Quik. The cells surrounding this amorphous substance have the classic appearance of granulosa cells.[76] Sometimes the cells can form tight groups, making it difficult to appreciate nuclear grooves.[7475] These cells may be mistaken for the flat mesothelial sheets often encountered in washings. In this regard, immunostains are helpful, as granulosa tumor cells are most commonly positive for vimentin, inhibin, calretinin, CD99 and smooth muscle actin. They may be positive for cytokeratin (punctuate staining), S100, and CD10, although with lesser frequency. Positive washings that accompany juvenile granulosa cell tumors are usually hypercellular with loosely cohesive sheets and single cells. Individual cells show moderate to abundant dense cytoplasm with occasional vacuoles. Nuclear indentation can also be seen.[717476]

Small cell carcinoma of the ovary has been described in peritoneal washing specimens.[77] In this report, the specimen contained both cell clusters and a population of single cells. The cells had a moderate amount of cytoplasm and nuclei with smooth nuclear membranes, and granular, clumped chromatin with prominent nucleoli. Displaced granulosa cells secondary to ovarian follicular cysts can be mistaken for small cell carcinoma or other metastatic carcinomas.[78] Malignant Brenner tumors are rare neoplasms with few reports describing their appearance in effusion specimens. In smears they appear hypercellular, with reactive mesothelial cells, lymphocytes and squamous neoplastic cells.[79] However, neoplastic squamous cells are more commonly associated with endometrioid adenocarcinoma with extensive squamous differentiation and less frequently with malignant transformation of mature teratomas.[80]

- Choricarcinoma in a pelvic washing. A multinucleate syncytiotrophoblast is present in a bloody background (Pap stain, ×400)

- Granulosa cell tumor in a pelvic washing. (Upper left) Sheet of granulosa cells (Pap stain, ×400). (Lower right) Note the distinct nuclear grooves in some granulosa cells (Pap stain, ×400). (Upper right) The cell block demonstrates the microfollicular pattern of an adult-type granulosa cell tumor created by numerous small cavities (Call-Exner bodies) (H and E, ×200). (Lower right) Tumor cells in this case were immunoreactive for inhibin

Non-ovarian gynecological tumors

All subtypes of endometrial carcinoma can be detected in pelvic washings [Figure 15]. As alluded to before, the role of peritoneal cytology in endometrial cancer is controversial. Published studies have shown contradictory results regarding the significance of positive cytology and survival. Endometrioid carcinomas tend to involve the peritoneal cavity only late in the disease, and typically when there is deep myometrial invasion. Extrauterine spread with serous carcinoma is more common than with the other types of endometrial carcinoma. Therefore, serous tumors are more often detected in pelvic washings. Also, synchronous serous carcinoma of the endometrium can be observed in fallopian tubes, ovaries and the peritoneum. Immunostains for epithelial markers (e.g., B72.3 and BerEP4) help detect and/or confirm the presence of endometrial carcinoma in washings, but will not distinguish these cell groups from benign epithelial entities such as endosalpingiosis. Endometrial carcinoma cells present in ascites or peritoneal washings constitutes stage IIIa disease (per FIGO staging).[5] Positive peritoneal washings in endometrial cancers with carcinoma confined to the uterine corpus or a polyp (T1 disease) is clinically problematic. In such cases, the possibility of iatrogenic contamination of washings should be raised. Fallopian tube carcinomas that can be detected in pelvic washings include the BRCA-related tubal carcinomas. Positive peritoneal washings in these patients indicate stage IIc disease (per modified FIGO staging).[81] These carcinomas (e.g., serous, endometrioid) resemble their ovarian counterparts.

- A well differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium is shown in a pelvic washing. (Upper and Lower left) Tumor cells containing neutrophils within intracytoplasmic mucin vacuoles can be seen. This is a common feature of mucin-producing adenocarcinomas (Pap stain, ×400). (Upper right) Some of the tumor cells demonstrate open vesicular-type chromatin (Pap stain, ×400). (Lower right) Cell block showing morphologically similar endometrioid adenocarcinoma tumor cells (H and E, ×200)

Mesenchymal tumors of the uterus that can be detected in pelvic washings include sarcomas, mainly leiomyosarcoma [Figure 16], endometrial and related stromal tumors, MMMT, and perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas). MMMT can present in fluid specimens with only their carcinoma component, rarely as sarcoma only, and most commonly with both components. In MMMT, adenocarcinoma is usually characterized by a papillary or acinar arrangement. The sarcomatous component of MMMT forms loose aggregates or isolated cells. The sarcoma cells are elongated or caudate with cyanophilic cytoplasm and large nuclei.[82] Leiomyosarcoma is the most common uterine sarcoma. They are aggressive tumors, even when confined to the uterus. Leiomyosarcoma is usually characterized by pleomorphic spindle tumor cells that resemble smooth muscle. Epithelioid and myxoid leiomyosarcomas are rare variants that can be seen in pelvic washings.[83] Endometrial stromal sarcomas in fluids are characterized by several loosely cohesive cellular sheets of atypical cells. The cells usually have round to oval nuclei with irregular nuclear membranes, occasional chromatin clumping, rare inconspicuous nucleoli, and rarely may exhibit a more epithelioid appearance.[8485] Recent data shows that peritoneal washing have no clear utility in non-tubo-ovarian malignancies or benign gynecologic tumors.[86] In fact, the current impact of washings in tubal carcinoma is also unclear.[86]

- Metastatic uterine leiomyosarcoma. The washing in this case shows rare highly atypical tumor cells present in a background of inflammatory cells and blood (Left ThinPrep Pap stain, ×400; Upper right cytospin Pap stain, ×200; Lower right cell block H and E, ×400)

Mesothelial lesions

Mesothelial proliferations of the peritoneum are very challenging on cytologic specimens. They include reactive changes, benign cystic lesions such as MPIC, WDPM, and diffuse peritoneal malignant mesothelioma. Mesothelial hyperplasia is a common response to chronic effusions, inflammation (e.g., pelvic inflammatory disease), endometriosis and gynecological tumors. Hyperplasia may present with the underlying condition and/or solitary or multiple small hyperplastic nodules. Reactive mesothelial cells seen in washings can have mild to moderate nuclear pleomorphism, multinucleation, mitotic figures, cytoplasmic vacuoles and psammoma bodies.

MPIC, previously called multicystic mesothelioma, is a rare benign mesothelial proliferation that occurs predominantly in women of childbearing age who have had previous abdomino-pelvic surgery, pelvic inflammatory disease, or endometriosis. These lesions are often incidental findings; however, they are associated with pelvic pain. Multiloculated cysts (which may grow up to 15 cm) are located mainly in the pelvis, but can extend into the abdominal cavity or present with free floating cysts.[87] When present in peritoneal washings these cytologic preparations are usually hypercellular, formed by a population of mesothelial and squamous metaplastic cells. The mesothelial cells can be arranged in different patterns, and form large monolayered clusters or variably sized clusters of cells, as well as manifest with just single isolated cells. Because cells can sometimes be atypical this may lead to a misdiagnosis of malignant mesothelioma. The cells can be polyhedral to spindle shaped. Their nuclei are usually round to oval, but nuclear grooves can be present. The chromatin is finely granular and small nucleoli can be seen. The background is composed of inflammatory cells and macrophages. Mitotic figures were not presented in one such series of peritoneal washings.[88] Interestingly, in this published series the authors noted that in the areas of squamous metaplasia, basal cells were focally positive for calretinin, whereas the superficial squamous metaplastic cells were negative. Malignant tumors that can mimic MPIC include rare cystic variants of malignant mesothelioma and serous tumors involving the peritoneum.

WDPM is a rare subtype of mesothelial tumor. It is considered a tumor of uncertain malignant potential. It usually occurs in the peritoneum of women over a wide age range. Chronic pelvic pain is commonly associated with this lesion, however, the diagnosis of WDPM is usually an incidental finding during surgery.[89] At the molecular level neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) gene alterations have been associated with this tumor.[90] In FNA cytology one can appreciate the uniformity of cells distributed in tubule-papillary clusters.[91] However, the mesothelial cells of WDPM in fluids can occur singly in addition to forming papillary clusters [Figure 17]. The tumor cells are monotonous with abundant cytoplasm, have distinct cell borders and slit-like intercellular spaces. The mesothelial cells are bland and mitotic figures are rare to absent. Irregular clusters and nuclear contours, cellular and nuclear enlargement, as well as mitoses are usually not present.[92] However, Hejmadi et al., reported an interesting case of WDPM where marked cytologic atypia was present.[93] WDPM frequently has hyalinized oval structures surrounded by a single layer of small uniform cells, resembling collagen balls. The presence of collagenous balls raises the possibility of serous tumor of low malignant potential, although immunohistochemical studies can be helpful in the distinction. WDPM are diffusely positive for calretinin and CK5/6, and are negative for MOC31, B72.3 and BerEP4. The reverse will be seen in serous tumors.

- Well differentiated papillary mesothelioma. (Upper left, ThinPrep Pap stain, ×400; Lower Left, cell block H and E, ×400)

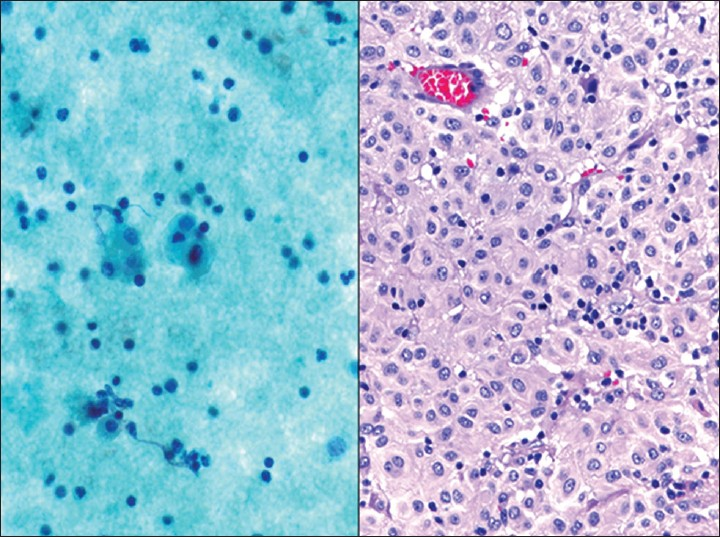

Primary malignant mesotheliomas can be cystic, papillary or diffuse. Diffuse peritoneal mesothelioma accounts for 10-20% of all mesotheliomas. It is less common than primary peritoneal serous carcinoma. These tumors are present in women as often as men, and typically from secondary exposure to asbestos. They present similarly to diffuse carcinomatosis, with peritoneal studding and ascites. The ovaries in these cases are generally not enlarged. Malignant mesothelioma has a poor prognosis, with an average survival of less than 2 years. The cytomorphology of mesothelioma in pelvic washings can be challenging due to its rarity, variable cytomorphology, and inability to assess for tissue invasion. In addition, the diagnosis of mesothelioma potentially has medical-legal implications. Therefore, without supportive clinical or radiological correlation and proper ancillary testing, it is often preferable to render a diagnosis of “atypical mesothelial proliferation” with a recommendation for tissue biopsy.[94] Malignant mesothelioma in fluids often results in highly cellular specimens. The most common pattern consists of large clusters of cells arranged in balls or papillary configurations [Figure 18]. Such clusters have an irregular, knobby border. The tumor cells tend to be larger than normal mesothelial cells, and also have larger nuclei and more prominent nucleoli. There is typically a spectrum of nuclear changes ranging from benign to atypical to malignant. Another important cytological feature is the lack of a foreign malignant population. Malignant cells in mesothelioma show “mesothelial” features such as dense central cytoplasm with lacy peripheral vacuoles, windows, binucleation and multinucleation.[95] Cases with a discohesive pattern of epithelioid or histiocytoid malignant cells may pose additional challenges, as well as cases with “signet ring” cells.[96] Immunostains are often needed to confirm the mesothelial nature of the cells. They should fail to stain with BerEp4, tumor associated glycoprotein/B72.3 (TAG/B72.3) and MOC31, but demonstrate immunoreactivity for calretinin (cytoplasmic and nuclear), CK5/6, D2-40 and WT1.[97] Although several immunostains have been reported to support a diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma (e.g., epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), glucose transporter-1(GLUT-1), and X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein), detection of a homozygous deletion of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) gene (p16) on chromosome 9p21 by fluorescence in situ hybridization appears to show the most promising results as a marker for malignancy in mesothelial proliferations. This abnormality is seen in over 70% mesotheliomas, and these cases typically have a worse prognosis.[98] The differential diagnosis of mesothelioma includes mesothelial hyperplasia, papillary endosalpingiosis, endometriosis, ovarian serous tumors, and metastatic adenocarcinoma.

- Malignant mesothelioma of the peritoneum. This ThinPrep specimen shows a large, complex, “mulberry” cluster of atypical mesothelial cells with scalloped (“knobby”) edges (Pap stain, ×400)

Non-gynecological tumors

Pelvic washings may uncover unexpected non-gynecologic tumors including metastatic non-Müllerian adenocarcinoma, mesenchymal tumors and lymphoproliferative conditions of the serosa. One such condition is pseudomyxoma peritonei. Pseudomyxoma peritonei refers to the presence of copious, thick mucinous or gelatinous material that fills the peritoneal cavity. Most cases develop from a low grade mucinous neoplasm, which mainly arises in the appendix or less frequently the ovary, that ruptures into the peritoneal cavity.[99100] Other possible primaries include the colon, gallbladder, pancreas, or stomach. In the 2010 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System, pseudomyxoma peritonei is classified into low and high grade categories based on histologic criteria which have prognostic significance.[101] In cytologic specimens a similar classification was attempted by Jackson et al., and concordance with histologic sections was obtained in 61 of 63 cases.[102] The fluid in these cases is grossly viscous, white/yellowish and may be difficult to smear. The cytological features are variable, and in washing specimens rarely include thick mucus only without tumor cells. In the majority of cases at least some clusters of epithelial cells are present with a background of mucin [Figure 19]. These clusters can be formed by a flat uniform population of neoplastic cells with smooth contours, regular nuclear contours and low N/C ratios. Also, the tumor cells can appear as bland, tall columnar cells with large cytoplasmic vacuoles containing mucin, or they can be more spindled shaped with wispy cytoplasm. The epithelial cells can also have a higher grade appearance with 3D clusters, hyperchromatic nuclei with clumped chromatin, and prominent nucleoli. Floating within the mucin there may also be few or no mesothelial cells and vacuolated histiocytes (muciphages). The presence of abundant mucin is abnormal in abdominopelvic fluid, even when a glandular component is not seen. Therefore, cases with only mucin present should be interpreted as suspicious for a mucinous neoplasm. The differential diagnosis includes metastatic mucinous carcinoma (which has more abundant and more atypical cells), or less likely a metastatic myxoid sarcoma.

- Pseudomyxoma peritonei. (Left) The case shown in the left image presented with only thick copious mucin in the peritoneal cavity (DQ stain, ×200). (Right) The case shown on the right had rare well differentiated groups of adenocarcinoma floating in abundant background mucin (Pap stain, ×200)

Finally, there are other rare tumors to keep in mind when evaluating challenging pelvic washings where the clinical findings, cytomorphology and initial ancillary studies may not be helpful. One such neoplasm is intra-abdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT). This is a highly malignant mesenchymal neoplasm that grows along the serosal surfaces, mainly in the abdominal cavity of young males. These patients usually present with large intra-abdominal masses, and sometimes with multiple smaller peritoneal “implants.” The undifferentiated round cells can be arranged in sheets and clusters. These cells have a high N/C ratio, round to oval nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli, and scant granular or vacuolated chromatin. Occasionally there may be nuclear molding, pseudorosettes, and stromal fragments present.[103] Immunostains show positivity for cytokeratin, EMA, desmin (paranuclear staining), neuron specific enolase (NSE), and WT1 (nuclear staining). DSRCT also exhibits a reciprocal translocation t (11;22) resulting in fusion of the Ewing sarcoma 1 (EWS1) gene on chromosome 22 and WT1 on chromosome 11. Other unusual epithelioid tumors to keep in mind include melanoma, epithelioid sarcomas [Figure 20], malignant rhabdoid tumors, PEComa and paraganglioma.

- Epithelioid gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). This female patient presented with a large pelvic mass initially thought to be of gynecological origin. (Left) The washing contained bland epithelioid cells with abundant cytoplasm that resembled reactive mesothelial cells (Pap stain, ×400). The tumor cells were immunoreactive for c-kit and the diagnosis of an epithelioid GIST was confirmed on the resection specimen (Right H and E, ×200)

CONCLUSIONS

Peritoneal washings in patients with abdominopelvic tumors are frequently submitted for cytologic evaluation. It is important to correlate the cytological findings in these washings with the surgical pathology of the resected tumor in all cases. Immunohistochemistry may be of limited value in pelvic washings because the presence of benign entities (e.g., endosalpingiosis) stain positively for epithelial and Müllerian markers. The utility of performing washings in benign and borderline tumors of the ovary, as well as several other gynecological malignancies, remains unclear. Furthermore, positive pelvic washing cytology is no longer used for staging of endometrial cancer. Peritoneal washings are also not included in staging cervical carcinoma. Peritoneal washing cytology is sometimes also used to document the spread of gastric or pancreatic carcinomas. Therefore, the cytopathologist must be prepared for a wide variety of morphologies in these specimens, recognize the utility and limitations of these specimens, and be aware of the differential diagnoses and possible pitfalls.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that they qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE. All authors participated in it design and coordination, and worked collaboratively to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) of all the institutions associated with this study as applicable. Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of Cyto Journal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind mode (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2013/10/1/7/111080

REFERENCES

- Experience with radioactive colloidal gold in the treatment of ovarian carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1956;71:553-68.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prognostic value of peritoneal cytology in gynecologic malignant disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110:773-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Carcinoma of the ovary.FIGO 26 th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95:S161-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative performance of the 2009 international Federation of gynecology and obstetrics’ staging system for uterine corpus cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1141-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manueal. Chicago: Springer; 2010.

- Peritoneal washing cytology in cervical carcinoma. Analysis of 109 patients. Acta Cytol. 1990;34:645-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peritoneal wash cytology in gastric carcinoma.Prognostic significance and therapeutic consequences. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:982-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Positive peritoneal lavage cytology is a predictor of worse survival in locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Am J Surg. 2010;199:657-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Art and Science of Cytopathology Vol 1. (2nd ed). Chicago: American Society of Clinical Pathology Press; 2012.

- Serous Cavity and Cerebrospinal Fluid Cytopathology. New York: Springer; 2012.

- Cytopathology of serous neoplasia of the ovary and the peritoneum: Differential diagnosis from mesothelial proliferations. Diagn Cytopathol. 1996;15:292-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Collagen balls” in peritoneal washings. Prevalence, morphology, origin and significance. Acta Cytol. 1992;36:466-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies on cytology and cytochemistry of cilioepithelial tumor cells in puncture of serous ovarian cystomas and cystadenocarcinomas. Z Krebsforsch. 1953;59:581-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serous psammocarcinoma of the ovary and peritoneum. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1990;9:110-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic findings of psammocarcinoma in peritoneal washings. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:263-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytohistologic correlation of peritoneal washing cytology in gynecologic disease. Acta Cytol. 1989;33:327-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ciliated adenocarcinoma of the ovary with evidence of serous differentiation: Report of a case. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2009;28:447-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ciliated carcinoma – A variant of endometrial adenocarcinoma: A report of 10 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1983;2:1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic features of ciliated adenocarcinoma of the cervix: A case report. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:187-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endosalpigiosis in peritoneal washings with benign gynecologic conditions: A report of 34 cases confirmed with PAX-8 immunohistochemical staining and correlation with surgical biopsy findings. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2012;1:S17-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic findings in peritoneal washings associated with benign gynecologic disease. Acta Cytol. 1988;32:139-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- The adjunctive value of CD10 immunostaining on cell block preparations in pelvic endometriosis. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:625-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Eosinophilic metaplastic atypia in exfoliated cells of ovarian endometriosis: A potential cytodiagnostic pitfall in peritoneal fluids. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;31:123-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Borderline ovarian tumors: Diverse contemporary viewpoints on terminology and diagnostic criteria with illustrative images. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:918-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peritoneal washing cytologic analysis of ovarian serous tumors of low malignant potential to detect peritoneal implants and predict clinical outcome. Cancer Cytopathol. 2012;120:238-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peritoneal washing cytology of ovarian tumors of low malignant potential: Correlation with surface ovarian involvement and peritoneal implants. Acta Cytol. 1998;42:1091-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- The histologic subtype of ovarian tumors affects the detection rate by pelvic washings. Cancer. 2004;102:150-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peritoneal washing cytology in gynecologic cancers: Long-term follow-up of 355 patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:980-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peritoneal washing cytology. Uses and diagnostic criteria in gynecologic neoplasms. Acta Cytol. 1984;28:105-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic identification of serous neoplasms in peritoneal fluids. Cancer. 2001;93:309-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subdividing ovarian and peritoneal serous carcinoma into moderately differentiated and poorly differentiated does not have biologic validity based on molecular genetic and in vitro drug resistance data. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1667-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Key features of extrauterine pelvic serous tumours (fallopian tube, ovary, and peritoneum) Histopathology. 2012;61:329-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Grading ovarian serous carcinoma using a two-tier system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:496-504.

- [Google Scholar]

- Micropapillary serous carcinoma of the ovary: Cytomorphologic characteristics in peritoneal/pelvic washings. Cancer. 2002;96:135-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic findings in peritoneal fluids from patients with ovarian serous adenocarcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1986;2:13-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of immunohistochemistry to gynecologic pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:402-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunohistochemical analysis of peritoneal mesothelioma and primary and secondary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum: Antibodies to estrogen and progesterone receptors are useful. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:67-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- h-caldesmon, calretinin, estrogen receptor, and Ber-EP4: A useful combination of immunohistochemical markers for differentiating epithelioid peritoneal mesothelioma from serous papillary carcinoma of the ovary. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1139-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of PAX8 and p53 is beneficial in recognizing metastatic carcinomas in pelvic washings, especially in cases with suspicious cytology. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:595-600.

- [Google Scholar]

- High-grade and low-grade pelvic serous neoplasms demonstrate differential p53 immunoreactivity in peritoneal washings. Acta Cytol. 2011;55:79-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extraovarian peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma: A case-control retrospective comparison to papillary adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;50:347-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mesothelioma of the pelvic peritoneum resembling papillary cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary: Case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1959;77:197-200.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intraperitoneal serous adenocarcinoma: A critical appraisal of three hypotheses on its cause. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:718-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: Evidence for a causal relationship. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:161-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Primary peritoneal” high-grade serous carcinoma is very likely metastatic from serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: Assessing the new paradigm of ovarian and pelvic serous carcinogenesis and its implications for screening for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;120:470-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: Its potential role in primary peritoneal serous carcinoma and serous cancer prevention. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4160-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peritoneal washing cytology in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomies: A 10-year experience and reappraisal of its clinical utility. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:683-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Value of mesothelial and epithelial antibodies in distinguishing diffuse peritoneal mesothelioma in females from serous papillary carcinoma of the ovary and peritoneum. Histopathology. 2002;40:237-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adenocarcinoma cells in effusion cytology as a diagnostic pitfall with potential impact on clinical management: A case report with brief review of immunomarkers. Diagn Cytopathol 2012 In press

- [Google Scholar]

- Ascitic fluid cytology of a malignant mixed Müllerian tumor of the peritoneum: A report of two cases with special reference to p53 status. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:281-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunocytochemistry of mesenteric malignant mixed müllerian tumour in peritoneal effusion cytology: Case report. Cytopathology. 2012;23:334-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ectopic decidua in abdominal washings found intraoperatively at cesarean section. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:740-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- The histologic type and stage distribution of ovarian carcinomas of surface epithelial origin. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004;23:41-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunohistochemistry in the distinction between primary and metastatic ovarian mucinous neoplasms. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:596-600.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunohistochemical expression of CDX2 in primary ovarian mucinous tumors and metastatic mucinous carcinomas involving the ovary: Comparison with CK20 and correlation with coordinate expression of CK7. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:1421-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytokeratins 7 and 20 in primary and secondary mucinous tumors of the ovary: Analysis of coordinate immunohistochemical expression profiles and staining distribution in 179 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1130-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Excessive formation of basement membrane substance in clear-cell carcinoma of the ovary: Diagnostic value of the “raspberry body” in ascites cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;16:500-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic features of clear cell carcinoma of the female genital tract. Diagnostic value of the “raspberry body” in nonexfoliative cytologic specimens. Acta Cytol. 2004;48:47-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clear-cell adenocarcinoma of the female genital tract: Presence of hyaline stroma and tigroid background in various types of cytologic specimens. Diagn Cytopathol. 2005;32:336-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytomorphologic features of immature ovarian teratoma in peritoneal effusion: A case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2005;33:39-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ovarian and omental ependymomas in peritoneal washings: Cytologic and immunocytochemical features. Diagn Cytopathol. 1986;2:62-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic features of malignant ovarian monodermal teratoma with an ependymal component in peritoneal washings. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1992;11:299-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chronic ovarian pregnancy mimicking an ovarian tumor diagnosed by peritoneal washing cytology: A case report. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:195-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Unusual ovarian malignancies in ascitic fluid: A report of 2 cases. Acta Cytol. 2010;54:611-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pelvic washing cytology of ovarian Sertoli-Leydig-cell tumor with retiform pattern: A case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:28-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic features of granulosa cell tumors in fluids and fine needle aspiration specimens. Acta Cytol. 2004;48:315-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Small-cell carcinoma of the ovary in peritoneal fluid. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;11:266-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Displaced granulosa cells in peritoneal washings: A rare diagnostic pitfall. Cytopathology. 2011;22:202-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ascitic fluid cytology in malignant Brenner tumor: A case report. Acta Cytol. 2010;54:598-600.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the ovary.Report of 37 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:823-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Carcinoma of the fallopian tube.FIGO 26 th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95:S145-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peritoneal cytology in malignant mixed müllerian tumors of the uterus. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;33:91-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peritoneal washing cytology findings of disseminated myxoid leiomyosarcoma of uterus: Report of a case with emphasis on possible differential diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:47-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peritoneal washing cytology of disseminated low grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: A case report. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:587-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytomorphologic features of low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:265-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- The clinical utility of peritoneal washing in gynecologic surgery and potential cost saving with elimination of unnecessary specimen processing. J Am Soc of Cytopathol. 2012;1:S17-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytology of benign multicystic peritoneal mesothelioma in peritoneal washings. Cytopathology. 2008;19:224-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma of the female peritoneum: A clinicopathologic study of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:117-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heterozygous loss of NF2 is an early molecular alteration in well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma of the peritoneum. Cancer Genet. 2012;205:594-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration of a well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma in the inguinal hernia sac: A case report and review of literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:748-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma in the pelvic cavity.A case report. Acta Cytol. 2003;47:88-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant transformation of a well-differentiated peritoneal papillary mesothelioma. Acta Cytol. 2003;47:517-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for Pathologic Diagnosis of Malignant Mesothelioma: 2012 Update of the Consensus Statement from the International Mesothelioma Interest Group. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012 In press

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytomorphologic features of primary peritoneal mesothelioma in effusion, washing, and fine-needle aspiration biopsy specimens: Examination of 49 cases at one institution, including post-intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy findings. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:414-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Signet-ring” cells – A caveat in the diagnosis of a diffuse peritoneal mesothelioma occurring in a lady presenting with recurrent ascites: An unusual case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:435-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Applications and limitations of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:316-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- The diagnostic utility of p16 FISH and GLUT-1 immunohistochemical analysis in mesothelial proliferations. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:619-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathology and prognosis in pseudomyxoma peritonei: A review of 274 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:919-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epithelial cells and other cytologic features of pseudomyxoma peritonei in patients with ovarian and/or appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: A study of 12 patients including 5 men. Cancer. 2000;90:17-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System (4th ed). Lyon: IARC; 2010.

- Gelatinous ascites: A cytohistologic study of pseudomyxoma peritonei in 67 patients. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:664-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- From conventional fluid cytology to unusual histological diagnosis: Report of four cases. Diagn Cytopathol 2011 [Epub ahead of print]

- [Google Scholar]