Translate this page into:

Cytomorphology of cervicovaginal melanoma: ThinPrep versus conventional Papanicolaou tests

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Primary cervicovaginal melanoma is a rare malignancy associated with a high risk of recurrence. Prior studies discussing the cytomorphology of cervicovaginal melanoma have been based primarily on review of conventional Papanicolaou (Pap) smears. The aim of this study was to evaluate cervicovaginal melanomas identified in liquid-based Pap tests, in comparison with features seen on conventional Pap smear preparation.

Materials and Methods:

Cases of cervicovaginal melanoma identified on Pap tests with concurrent or subsequent histopathologic confirmation were collected from the Baystate Medical Center cytopathology files and personal archives of the authors over a total period of 34 years. All cytopathology (n = 6) and the available histology slides (n = 5) were reviewed. Cases were analyzed regarding clinical, histopathologic and cytomorphological findings.

Results:

A total of six cases with invasive cervicovaginal melanoma diagnosed on Pap tests were identified. Most patients were postmenopausal with contact bleeding, correlating with surface ulceration (identified in biopsy/excision material in 5/5 cases). Most cases had deeply invasive tumors (5/5: modified Breslow's thickness > 5 mm and Chung's level of invasion IV/V). Pap tests included four ThinPrep and two conventional smears. Overall, ThinPrep Pap tests exhibited a higher ratio of tumor cells to background squamous cells. While all Pap tests were bloodstained, tumor diathesis was prominent only within conventional smears. Melanoma cells were present both as clusters and scattered single cells in each Pap test type. Both the preparations contained epithelioid tumor cells, whereas spindled tumor cells were seen in only two ThinPrep cases. Prominent nucleoli and binucleation of tumor cells were seen in both the preparations. Melanin pigment was identified in only ThinPrep (3/4) cases and nuclear pseudo-inclusions in one conventional Pap smear. Cell blocks were made in three ThinPrep cases and immunocytochemistry (S-100, HMB45, Melan-A) performed on additional vial material (one ThinPrep slide and one cell block) was immunoreactive in melanoma cells.

Conclusion:

Primary cervicovaginal melanoma, a rare malignancy seen predominantly in postmenopausal women, may be successfully diagnosed in either ThinPrep Pap tests or conventional Pap smears. While ThinPrep Pap tests did not demonstrate morphological advantage over conventional smears, liquid-based cytology specimens did provide additional material for cellblock preparation and immunocytochemical evaluation in a subset of cases.

Keywords

Cervix

conventional smear

cytology

melanoma

Pap test

ThinPrep

vagina

INTRODUCTION

Primary cervicovaginal melanoma is a rare malignancy, constituting approximately 9% of all vaginal neoplasms.[1] Melanoma involving the uterine cervix is even more infrequent, with only about 60 cases reported to date.[2] These tumors have a high mortality rate.[3] These patients usually present late with advanced disease. Moreover, the varied cytomorphological spectrum (e.g. epithelioid, spindled, combined patterns, and amelanotic features) that may occur with melanoma (“the great masquerader”) combined with the rarity of these tumors at this site certainly pose a diagnostic challenge to cytopathologists. Most prior studies discussing the cytomorphology of cervicovaginal melanoma have been based primarily on review of conventional Papanicolaou (Pap) smears. There have been only very few case reports describing the findings of cervicovaginal melanoma[4–8] using liquid-based cytology.[9] The use of liquid-based automated Pap test preparations for the diagnosis of cervicovaginal melanomas has not been evaluated. The aim of this study was to assess the cytomorphological features of cervicovaginal melanomas observed in liquid-based preparations in comparison with conventional Pap tests.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective review spanning 34 years of the pathology computer database at Baystate Medical Center and the personal teaching archives of the authors was performed for melanomas involving the vagina and uterine cervix. Data regarding patient demographics (age, gender), clinical findings (presentation, outcome), histopathology (melanoma prognostic features), cytology specimen preparation (direct smear, ThinPrep, cell block), cytomorphology (cellularity, diathesis, tumor cell features including necrosis, epithelioid or spindle cell shape, cohesion, pigmentation, multinucleation, nucleoli, nuclear inclusions) and ancillary studies (immunocytochemistry) were recorded. Detailed clinical history was available in only three cases. All cytology slides and available histopathology and ancillary study slides were reviewed. Accrued data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

A total of six patients were identified with invasive cervicovaginal melanoma, four from departmental archives and two from the authors′ personal archives.

Clinical findings

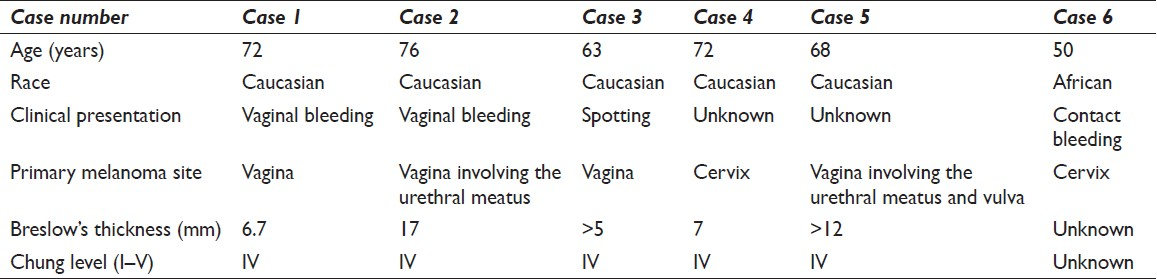

Clinical details of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The average patient age was 67 years (range 50-76 years). Five patients were Caucasians and one was African in descent. Most patients presented with postmenopausal bleeding (4/6). Contact bleeding in these patients correlated with the presence of tumor surface ulceration identified in biopsy/excision material in 5/5 cases. Most cases (5/5) had deeply invasive tumors; all were modified Breslow's thickness > 5 mm with a Chung level of invasion IV/V.[10] The diagnosis of melanoma was confirmed in all cases by biopsy material [Figure 1]. In cases where information was available about where tumors were found, melanomas were located on the anterior (1/4), posterior (1/4), anterior and posterior (1/4) and lateral (1/4) vaginal wall. All patients were treated with surgery and radiation therapy. Local recurrence was noted in two cases and metastases (to the groin and pleura) were seen in two cases. One patient (case 1) had three recurrences with malignant pleural effusions and ascites. Another (case 2) relapsed with multiple liver, pulmonary and external iliac lymph node metastases. Two patients had a prior history of a concomitant malignancy (pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma and papillary transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder). A diagnostic workup performed in all cases did not reveal malignant melanoma at any other location.

Cytopathology findings

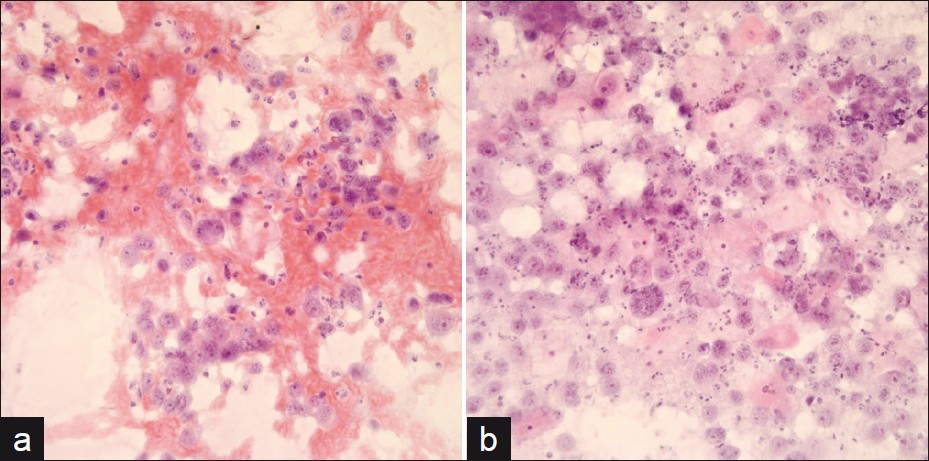

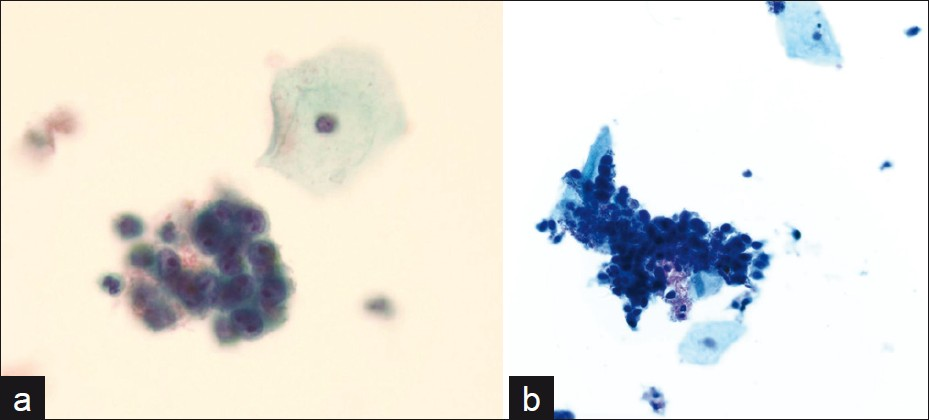

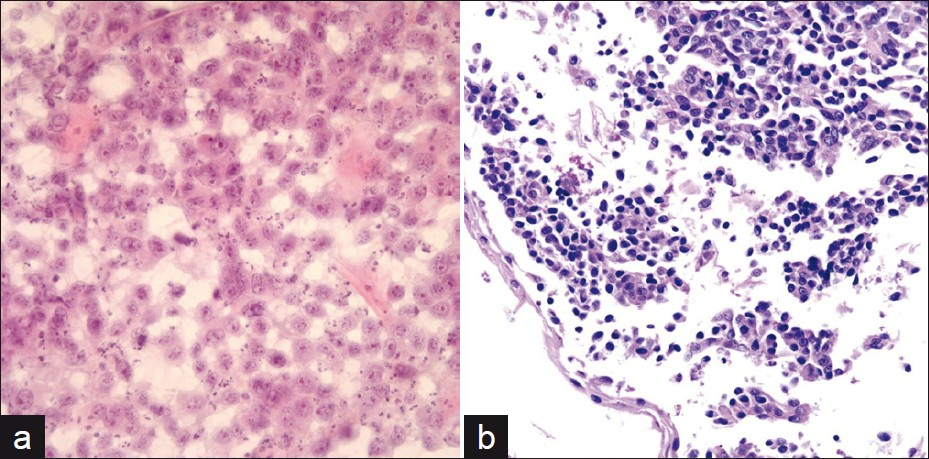

The cytological specimens reviewed included four Thinprep Pap tests and two conventional Pap smears. Overall, ThinPrep Pap tests exhibited a higher ratio of tumor cells to background squamous cells. While all Pap tests were bloodstained, tumor diathesis was most prominent with conventional smears [Figure 1]. The tumor diathesis obscured some of the tumor cells. Melanoma cells were present both as clusters [Figure 2] and dissociated single cells [Figure 3] in each Pap test type. Both the preparations contained epithelioid tumor cells, whereas spindled tumor cells were seen in only two ThinPrep cases. Prominent nucleoli and binucleation of tumor cells were seen in both the preparations. Melanin pigment was identified in only ThinPrep (3/4) cases and tumor cell nuclear pseudo-inclusions in one conventional Pap smear. Cell blocks were prepared in three ThinPrep cases (two with contributory material and one acellular). Immunocytochemistry (S-100, HMB-45, Melan-A) performed on one additional ThinPrep slide and one cellblock demonstrated immunoreactivity in melanoma cells.

- Conventional Pap smear showing malignant melanoma tumor cells associated with (a) a bloody background (Pap stain, original magnification ×200) and (b) necrotic inflammatory tumor diathesis (Pap stain, original magnification ×400)

- ThinPrep Pap tests showing clusters of melanoma tumors cells with (a) a bloody background (Pap stain, original magnification ×400) and (b) relatively clean background (Pap stain, original magnification ×200)

- (a) Conventional Pap smear showing abundant dissociated tumor cells (Pap stain, original magnification x200), (b) Cell block showing dyshesive tumor cells (H and E stain, original magnification ×200)

DISCUSSION

The overall annual incidence of melanoma of the female genital tract is less than 0.2 per 100,000 women. Of these, the majority arise in vulvar skin, accounting for 3-7% of melanomas in women.[11] Primary cervicovaginal malignant melanomas are uncommon tumors comprising approximately 2-5% of female genital tract melanomas. Fewer than 250 cases of vaginal melanomas and 60 cases of cervical melanomas have been reported to date.[11] Nigogosyan et al. described the presence of melanoblasts in vaginal mucosa in 3% of women, which could theoretically explain the origin of melanomas in this location.[12] Blue nevi in the cervix and vagina have also been described.[1314] In our study, most cases had deeply invasive tumors with a mean modified Breslow's thickness of >9.54 mm, which is significantly higher than the 2.91 mm recorded in a series of 19 cases of vaginal melanoma by Chung et al.[10] However, the Chung level of invasion was IV/V in all of our cases, similar to that observed by the authors in their study.[10]

Vaginal melanomas are typically seen in postmenopausal women with a peak incidence in the sixth and seventh decades.[15] Cervical melanomas, on the other hand, have been reported in a wider age distribution at diagnosis, ranging from 20 to 78 years.[1617] In our study, the median age at diagnosis for vaginal melanomas was 70 years, and the two patients with cervical melanomas were 50 and 72 years of age. Vaginal melanomas do not appear to exhibit a racial predisposition, in contrast to vulvar melanomas, which preferentially affect Caucasian women.[18] Only one of the patients in this series was of African descent. Similar to previous studies,[1314] abnormal vaginal bleeding associated with tumor surface ulceration was the most common presenting symptom. Ulceration in these tumors likely contributes to the bloodstained tumor diathesis identified in the cytologic specimens. The presence of ulceration, however, does not necessarily increase the likelihood of obtaining exfoliated tumor cells, as has been suggested by some authors.[19] Medek et al. reported a case of an ulcerated oral melanoma that did not shed melanoma cells in a cytologic preparation until the tumor had been traumatized by needle aspiration.[20]

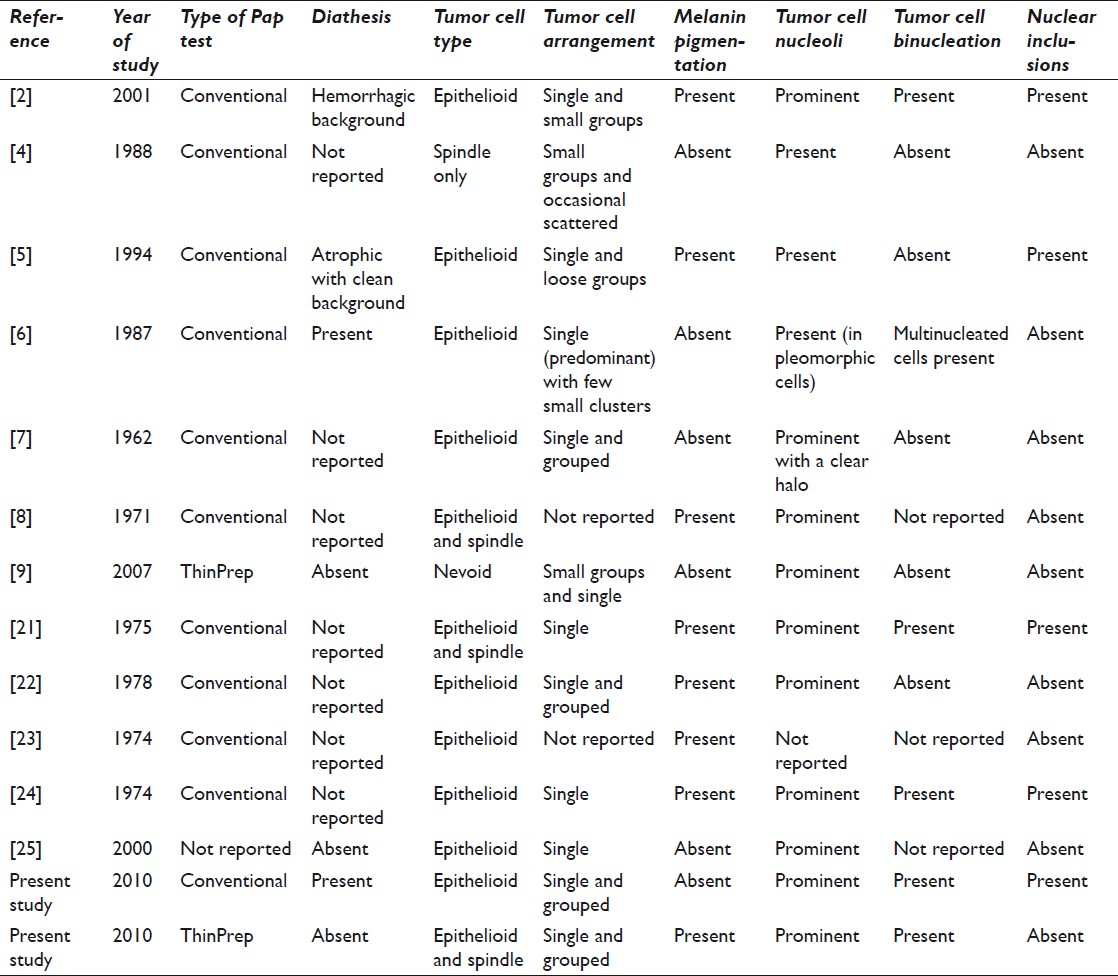

The diagnosis of melanoma was established on concomitant cytologic and biopsy material obtained in most of our cases. However, melanoma in this location may first be detected on a Pap test. Most of the case reports in the literature describing the cytological findings of melanoma in the lower female genital tract were based on conventional Pap smears [Table 2]. In fact, the only case series published in 1974 by Masubuchi et al., describing the cytopathology of malignant melanoma of the vagina, involved conventional Pap tests.[21] We intended to compare the cytological features of cervicovaginal melanomas identified in liquid-based Pap tests compared to those seen in conventional Pap smear preparations. The small study size in our series of this rare neoplasm, including previously published cases, makes it difficult to compare the sensitivity and specificity of these two techniques reliably. Nevertheless, we did not find any morphological advantage with ThinPrep Pap tests. Whereas melanoma cells are typically described as dyshesive and isolated on smears,[19] in the present study they were also observed forming clusters in each Pap test type. Several clusters with overlapping cells were difficult to interpret. Prominent nucleoli are a well-recognized cytomorphological feature of melanoma cells[7821–25] and were seen in all cases of the present study. Melanin pigment, when present, is a helpful finding in differentiating melanoma from other high-grade tumors such as poorly differentiated carcinoma, sarcoma, and anaplastic lymphoma. However, melanin may be focal and not represented in Pap test material or could be absent in the case of an amelanotic melanoma. It is unclear why melanin pigment was identified in only three of the ThinPrep cases of this study. Nuclear pseudo-inclusions (also called Apitz bodies), considered to be one of the characteristic features of melanoma,[21] were only seen in one conventional Pap smear. Most other investigators have similarly not been able to identify these nuclear inclusions in cytological smears.[7823–25] While ThinPrep Pap tests did not provide a morphological advantage over conventional smears, liquid-based cytology specimens did offer additional material for cell block preparation and immunocytochemical evaluation in a subset of our cases. The advantages of cell block preparation and immunocytochemistry performed on procured cytology material has been demonstrated by several investigators.[26] Cell blocks and immunocytochemistry were utilized as adjuncts to confirm a diagnosis of malignant melanoma in three cases.

In summary, we present to the best of our knowledge the largest cytopathology series of six cervicovaginal melanomas, comparing liquid-based cytology with conventional Pap tests. These mucosal melanomas frequently present as ulcerated masses, resulting in high cellularity with characteristic melanoma tumor cells, even on conventional Pap tests. Although the number of cases reported in the series is limited, the type of preparation method (conventional, Thinprep) did not appear to confer a cytomorphological advantage with respect to making a diagnosis of melanoma. ThinPrep cases, however, did impart the advantage of additional material for cell block preparation and immunocytochemistry.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

No competing interest to declare by any of the authors.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved. All authors qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author. Each author participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The study was undertaken as an Intradepartmental cytology-histology correlation/audit and an academic exercise. IRB approval was obtained. At all times, patient confidentiality was maintained. Authors take responsibility to maintain documentation in this respect.

EDITORIAL / PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model(authors are blinded for reviewers and reviewers are blinded for authors)through automatic online system.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2010/7/1/25/75666

REFERENCES

- Câncer of the vagina. In: Ries LA, Young JL, Keel GE, Eisner MP, Lin YD, Horner MJ, eds. SEER Survival Monograph: Cancer Survival Among Adults: U.S. SEER Program, 1988-2001, Patient and Tumor Characteristics.. 2007. p. :156. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program. Bethesda, MD: NIH Pub. No. 07-6215

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix: Report of a case diagnosed by cervical scrape cytology and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;25:108-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mucosal melanoma of the female genitalia: A clinicopathologic study of forty-three cases at Duke University Medical Center. Surgery. 1998;124:38-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix from Papanicolaou smears.A case report. Acta Cytol. 1987;31:73-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The exfoliative cytology and histogenesis of an early primary malignant melanoma of the vagina. Acta Cytol. 1962;6:245-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary malignant melanoma of the vagina. A case report. Acta Cytol. 1971;15:179-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nevoid melanoma of the vagina: Report of one case diagnosed on thin layer cytological preparations. Cytojournal. 2007;4:14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant melanoma of the vagina - report of 19 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1980;55:720-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Management of primary melanoma of the female urogenital tract. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:973-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Melanoblasts in vaginal mucosa.Origin for primary malignant melanoma. Cancer. 1964;17:912-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Melanotic, germ cell, lymphoid and secondary tumors of the cervix. In: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, eds. ‘WHO Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs’. Geneva: International agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2003. p. :287-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Melanotic, germ cell, lymphoid and secondary tumors of the cervix. In: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, eds. ‘WHO Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs’. Geneva: International agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2003. p. :308-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix: Case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75:170-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix: Case report with world literature review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1999;18:265-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant melanoma of the vulva and vagina in the United States: Patterns of incidence and population-based estimates of survival. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1225-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical and vaginal cytology. In: Cibas ES, Ducatman BS, eds. Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates (2nd ed). Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 2003. p. :51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Definitive cytopathologic characteristics of primary oral melanoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1969;27:237-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant melanoma of the vagina.A case diagnosed cytologically. Acta Cytol. 1974;18:535-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytological diagnosis of a primary malignant melanoma of the vagina. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1975;82:74-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- HMB-45 staining for cytology of primary melanoma of the vagina.A case report. Acta Cytol. 2000;44:1077-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Utility of cell block preparations in cytologic specimens diagnostic of lymphoma. Acta Cytol. 2010;54:236-7.

- [Google Scholar]