Translate this page into:

Serous fluid: Reactive conditions

*Corresponding author: Nirag Jhala, MD Professor, Director Anatomic Pathology, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Temple University Hospital, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University Philadelphia, PA, USA. nirvigyan@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Jhala NC, Jhala DN, Shidham VB. Serous fluid: Reactive conditions. CytoJournal 2022;19:14.

HTML of this article is available FREE at: https://dx.doi.org/10.25259/CMAS_02_06_2021

Abstract

This chapter highlights the steps that would help to analyze any fluid. It highlights importance of knowing gross analysis of fluid along with biochemical information. These parameters along with clinical information are very important in arriving at a differential diagnosis. Morphologic appearances in the fluid can often become challenging and occasionally reactive conditions can reveal changes that may mimic malignancies. This chapter provides not only a framework of approach to assessment of fluid cytology but also shows how to distinguish some of the challenging reactive conditions from the diagnosis of carcinoma. The chapter also utilizes two cases to demonstrate approach to reactive conditions. This review article will be incorporated finally as one of the chapters in CMAS (CytoJournal Monograph/Atlas Series) #2. It is modified slightly from the chapter by the initial authors in the first edition of Cytopathologic Diagnosis of Serous Fluids.

Keywords

Serous fluid

cell-block

Immunohistochemistry

Transudate

Exudate

Chylous effusion

Pseudochylous effusion

Empyema

LE cell phenomenon

Tuberculosis

Eosinophilia

INTRODUCTION

Effusions of serous cavities (of the pleural space, peritoneal cavity, or pericardial space) are one of the more common manifestations of a systemic disease; however, in some instances they are reflections of regional pathology from altered homeostasis of fluid collection. It should also be noted that effusions are never ‘variations of normal’ but rather the result of an underlying pathologic process that needs to be accurately characterized both for diagnostic and for management purposes.

It is estimated that pleural effusions may affect approximately 1.3 million individuals each year in United States. Whereas most effusions are associated with reactive conditions, it is not infrequent to find malignancies as the underlying cause, which portends a very unfavorable prognosis for patients irrespective of the site. Cytologic evaluation of effusion samples plays a key role in distinguishing reactive conditions from malignancies.[1-3]

Coming to an accurate diagnosis for a reactive condition requires understanding of the basic pathogenesis as well as integration of clinical, radiology, and results of ancillary studies.

PATHOGENESIS IN BRIEF

The principal function of physiologic (submacroscopic) fluid in cavities (pleural, peritoneal, or pericardial spaces) is to provide a frictionless surface between two membranes. Altered homeostasis, including increased production, seepage from an adjacent structure or lack of absorption of accumulated fluid into or from these spaces, leads to abnormal collection of fluid.[1]

The following basic mechanisms may help better define the basic underlying pathogenesis for the accumulation of fluid in the serous cavities:

Increased capillary hydrostatic pressure in the systemic and/or pulmonary circulation (e.g. congestive heart failure, superior vena caval syndrome)

Reduced intravascular oncotic pressure (e.g., hypoalbuminemia, hepatic cirrhosis)

Increased permeability of the membranes or capillaries (e.g., neoplastic disease, uremia, pancreatitis, pulmonary embolus)

Altered pressures in a serous space whether associated with lack of expansion of an adjacent structure (e.g., lung from tumor) or marked increase in pleural surface area (e.g. extensive atelectasis, mesothelioma)

Decreased lymphatic drainage or rupture of major lymphatic channels (e.g., chylosis, malignancy, trauma).

CLINICAL HISTORY

Predilections by gender

In general, the incidence is equal between both the sexes; however, effusions associated with certain systemic diseases show some sex predilection in parallel with the general distribution of these diseases in the population. For example, it is noted that effusions associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are observed more frequently among women, whereas effusions associated with chronic pancreatitis and rheumatoid effusions are more frequently noted in men.

Predilections of laterality with pleural effusions

Systemic diseases are often associated with bilateral pleural effusions, whereas isolated unilateral effusions occur more frequently with regional pathology. Isolated right-sided pleural effusions commonly occur with subphrenic or intrahepatic abscess formation, amebic liver abscess, Echinococcus infection, cirrhosis, liver transplantation, and Meigs’ syndrome. Isolated left-sided effusions are more frequently noted with esophageal rupture, pancreatic disease, especially pancreatitis, splenic abscess, splenic infarction, diaphragmatic hernia, pericardial disease, or following coronary artery bypass surgery.

EXAMINATION OF SEROUS FLUID: A SYSTEMATIC APPROACH TO DIAGNOSIS

It is recommended that at least 30–50 mL fluid (up to 1000 mL) should be sent for cytologic analysis. For patients with bilateral pleural effusions, thoracentesis of either side provides similar information.

Gross examination: type of fluid and possible etiology

Fluid appearances have been classified into many categories by various observers. Of these about eight different appearances have been well described with very good interobserver concordance.[4] These eight gross appearances comprise: watery (light yellow), serous (yellow), blood-tinged (reddish), bloody (dark red, similar to blood), purulent (pus), milky (white and less thick than pus), turbid (yellow, but viscous or cloudy), and others (brownish, greenish, black, etc.). In daily practice, effusions can be classified into two major categories: non-bloody and bloody effusions.

Special types of effusions

Bloody effusions[4,5]

Bloody effusions (hemothorax, hemopericardium, and hemoperitoneum) are considered when the fluid is homogenously red or dark brown, shows hemosiderin pigment, and the hematocrit of the effusion is 10% or greater of the blood hematocrit. Occasional blood-tinged fluids may be noted as a result of trauma associated with a procedure. Recovery of such trauma-associated fluids shows a decreasing gradient of blood (hematocrit) as compared to a true ‘bloody effusion.’

Bloody effusions are more likely to be associated with an underlying malignancy. The most frequent benign causes of bloody pleural effusions include parapneumonic and post-traumatic pleural insults. Table 1 lists some of the more frequent causes for bloody effusions.

| Para pneumonic effusions |

| Post-traumatic effusions |

| • Post-cardiothoracic procedures and surgeries |

| •Thoracic cavity vascular damage |

| Pulmonary embolism |

| Acute aortic dissection |

| Pancreatitis |

| Asbestos exposure associated pleural effusion |

| Endometriosis |

| Sarcoidosis |

| Intralobar pulmonary sequestration |

| Some Infections –e.g. Bacillus anthracis |

Chylous effusion[5,7-9]

Chylothorax is the accumulation of lymphatic fluid (chyle) in the pleural space due to disruption of the thoracic duct or another major lymphatic vessel. It more commonly occurs in the pleural space rather than peritoneal or pericardial cavities. In post-traumatic cases, the fluid accumulates rapidly following injury (usually within 2–10 days), whereas those cases with gradual onset of the effusion often have a different pathologic cause, including malignancies, more specifically lymphoma. Chylous effusions should be distinguished from pseudochylous effusions since they suggest a different pathogenesis and could be observed in a myriad of other conditions, including infections such as tuberculosis.

Causes

Some of the more common causes of chylous effusions are trauma to the lymphatic vessels, occurring either from a surgical intervention (e.g., transplants, cardiac surgeries, thoracostomy tubes), thrombosis in a subclavian indwelling catheter or following non-surgical causes (e.g., ‘boxer’s chest,’ penetrating gunshots, stab wounds, blast and crush injuries). On many occasions, conditions associated with chylothorax are idiopathic. This, in fact, is one of the most common presentations associated with pleural effusion in the newborn. In adults, constrictive pericarditis, cirrhosis, and lymphangiomyomatosis have been reported to be associated with chylous effusions. They are also frequently noted with malignancies.

TRANSUDATE VS EXUDATE[10,11]

Distinguishing whether a fluid is a transudate or an exudate is often the initial step in the analysis of effusions and may help define the basic underlying etiopathogenesis of the effusion [Tables 2-4]. A transudate is an ultrafiltrate of plasma associated with intact vasculature, and usually results from increased hydrostatic pressure and decreased oncotic pressure. In contradistinction, exudative fluids are generally a result of disruption of capillaries or actively altered capillary permeability. Thus, an exudative fluid more frequently parallels the plasma content. While there are many causes for exudative fluid as enumerated below, exudates are more frequently noted with malignancies and infectious/inflammatory processes [Table 3].

| Congestive heart failure |

| Cirrhosis |

| Nephrotic syndrome |

| Peritoneal dialysis |

| Hypo proteinemia (e.g. severe starvation) |

| Superior vena cava obstruction |

| Malignancies |

| Infectious diseases |

| Pancreatic diseases (acute or chronic pancreatitis, pseudocyst, pancreatic abscess), |

| Intra abdominal abscess (e.g. subphrenic, intrasplenic, intrahepatic) |

| Esophageal perforation (spontaneous/iatrogenic) |

| Abdominal surgery |

| Collagen vascular diseases/immune-mediated diseases: |

| •Rheumatoid arthritis |

| •Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| •Sjögren syndrome |

| Familial Mediterranean fever |

| Uremia |

| Therapy-associated effusions–e.g. nitrofurantoin, dantrolene, methysergide, bromocriptine, amiodarone, procarbazine, methotrexate, ergonovine, ergotamine, oxprenolol, maleate, practolol, minoxidil, bleomycin, interleukin-2, propylthiouracil, isotretinoin, metronidazole, mitomycin |

| Pulmonary embolism |

| Hypothyroidism |

| Transudates in patients following diuretic therapy. |

| Pericardial disease (inflammatory or constrictive) |

| Atelectasis |

| Sarcoidosis |

| Amyloidosis |

While most described criteria provide a working guideline, it is not always possible to characterize a fluid into an exudate or a transudate. In a patient with a transudative effusion, therapy with diuretics may lead to reduction in water content and may result in altered protein concentration. Further characterizing a fluid into one of the two types (transudate or exudate) provides only a general guideline for the possible underlying etiology.

BIOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS

The following tests may aid in arriving at etiologic possibilities.

Glucose estimation

Low glucose content in effusion samples is observed more frequently in patients with tuberculosisand rheumatoidarthritis-associated effusion.

Amylase levels

High amylase content is noted more frequently as a result of chronic pancreatitis or its sequelae.

Adenosine deaminase levels

Fluids from patients with tuberculosis show adenosine deaminase levels above 45 IU/L.

BIOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS

Cultures should be performed in addition to morphologic assessment, combined with special stains for highlighting organisms to characterize infectious organisms in a suspected case or when derived from an immunocompromised host.[12]

Morphology and histochemical stains

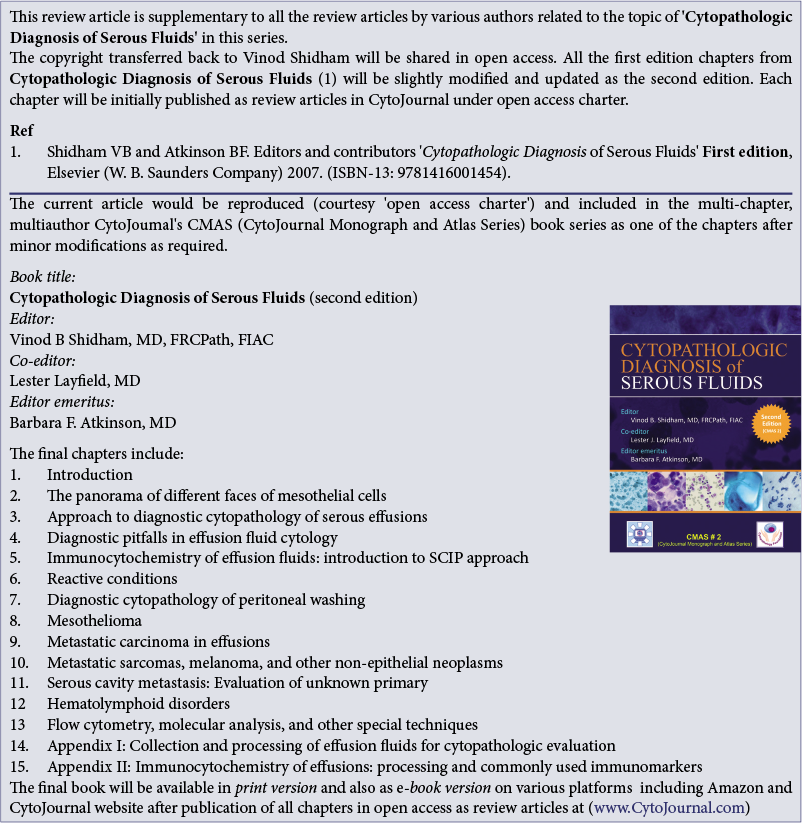

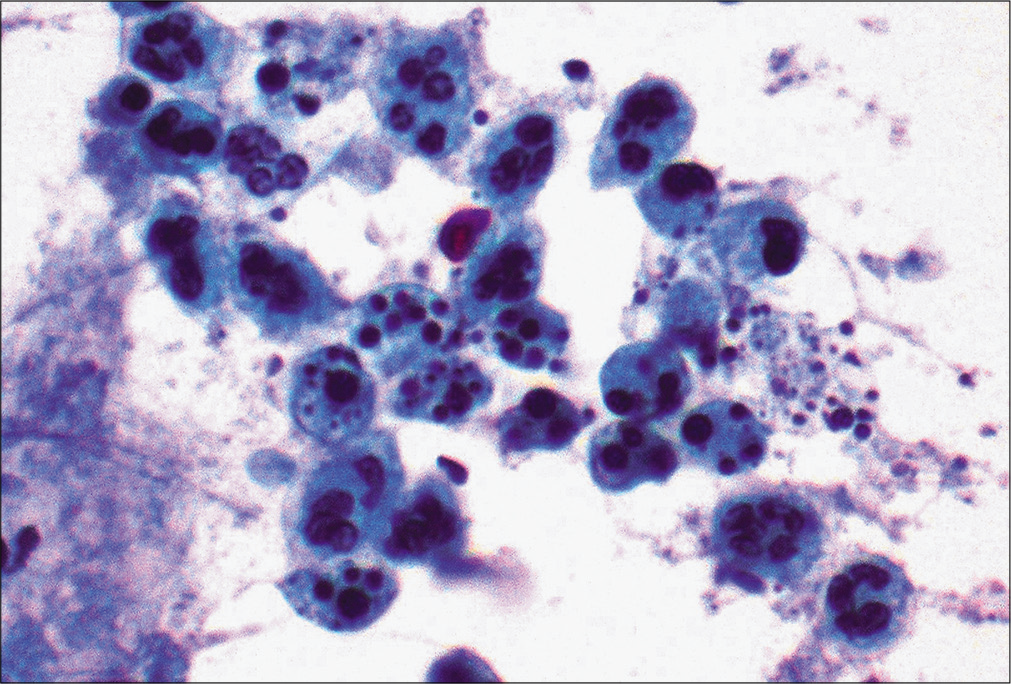

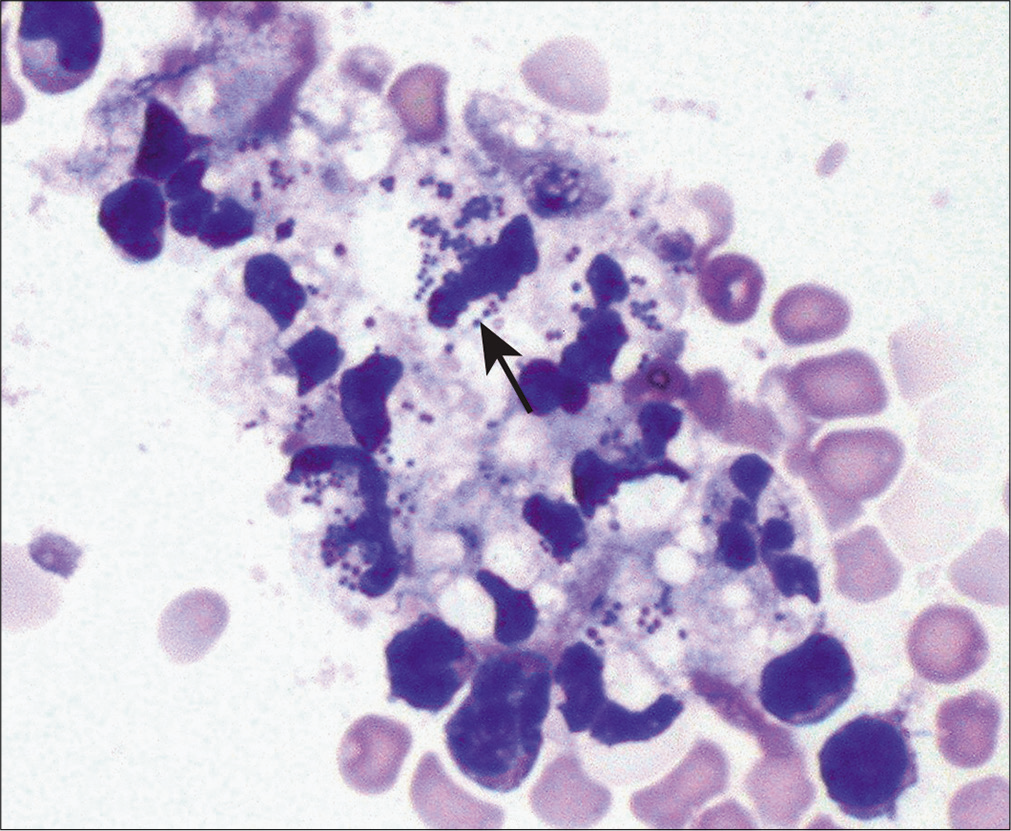

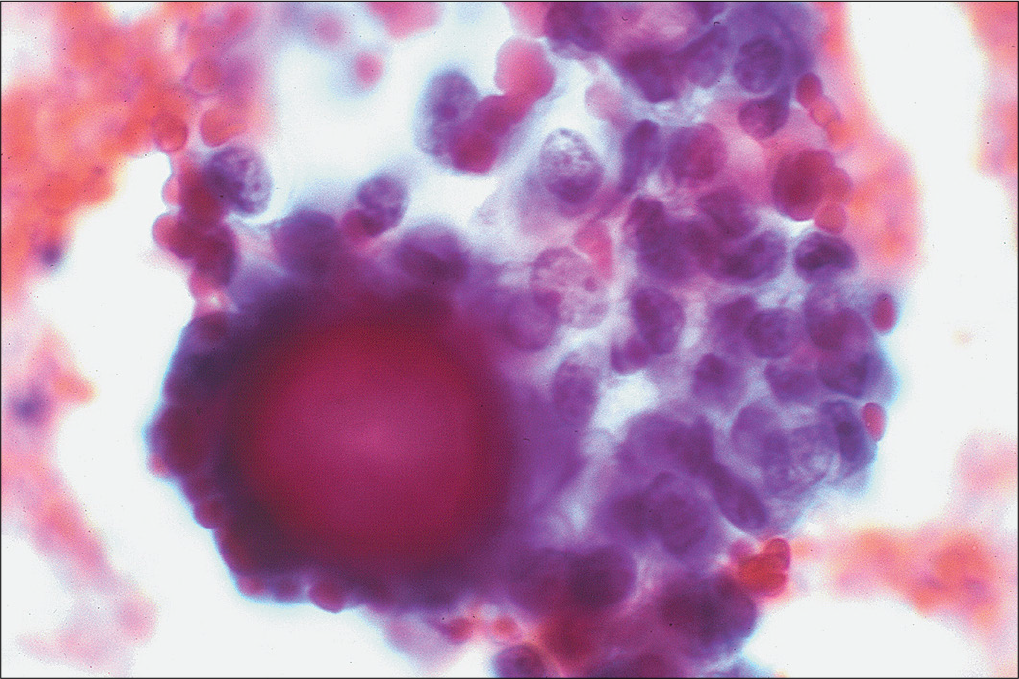

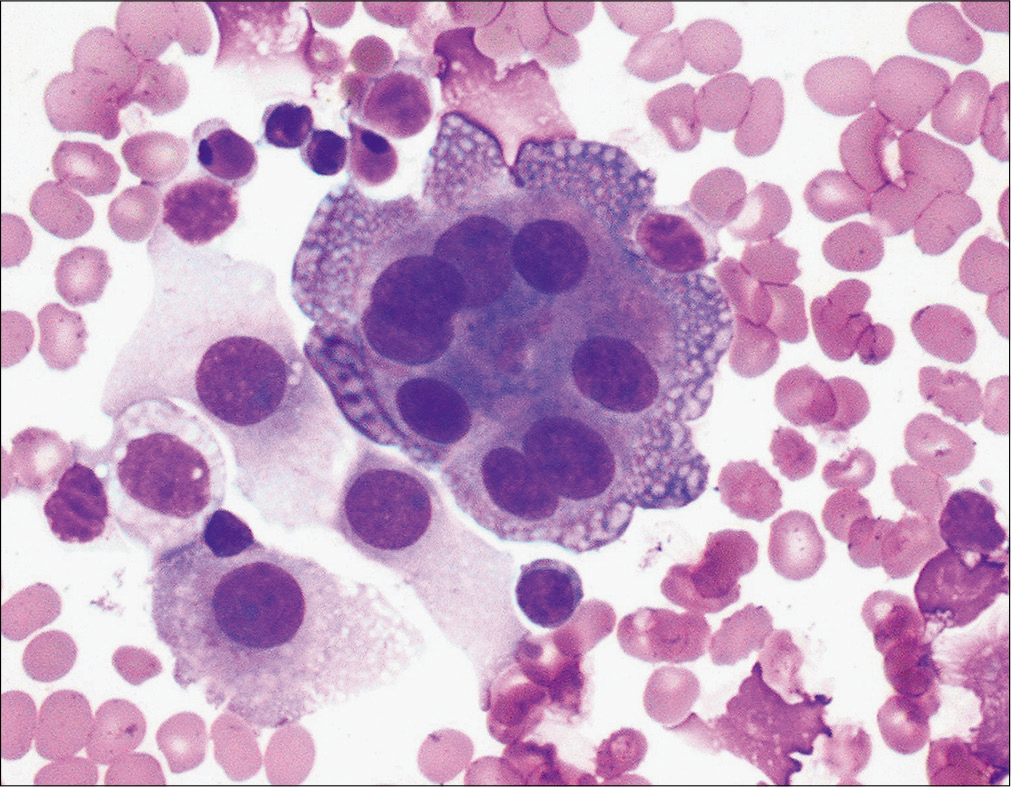

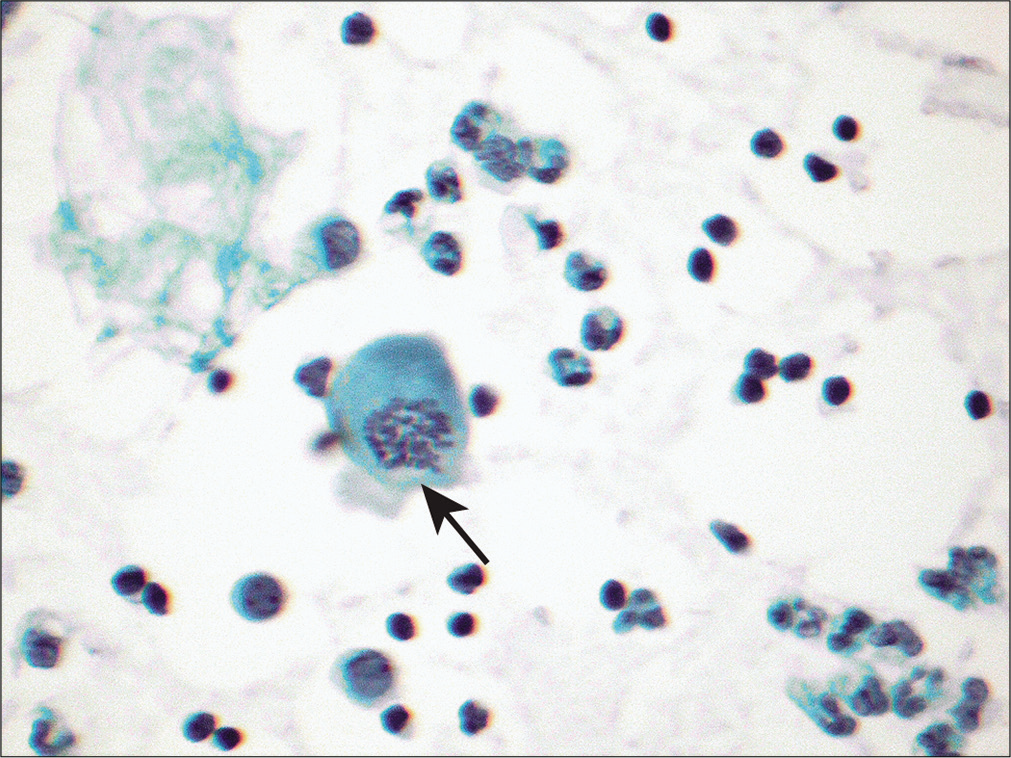

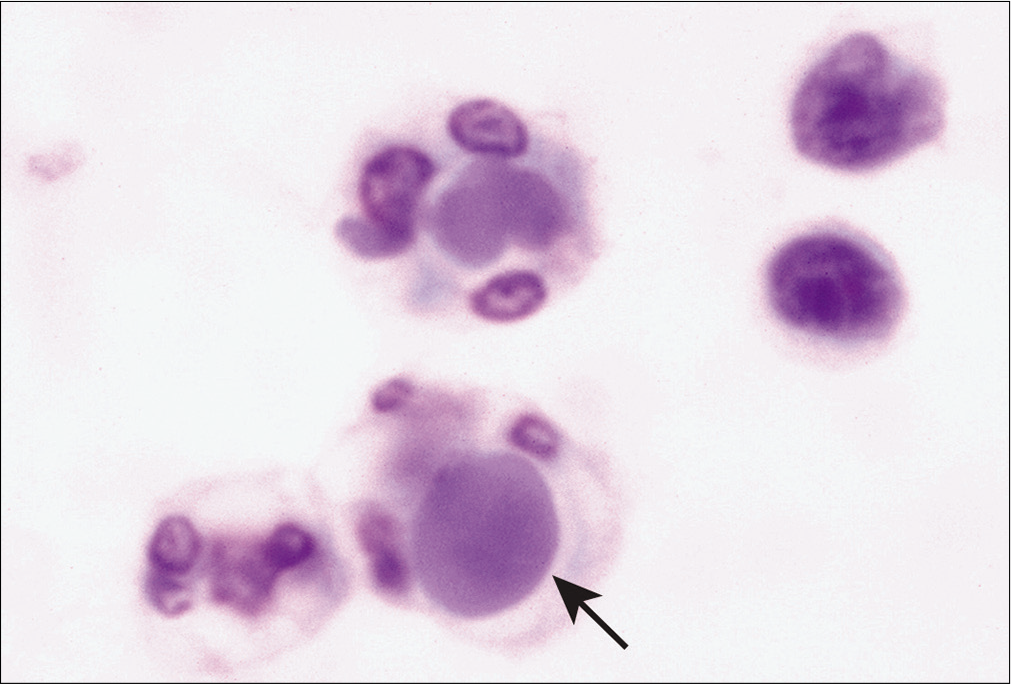

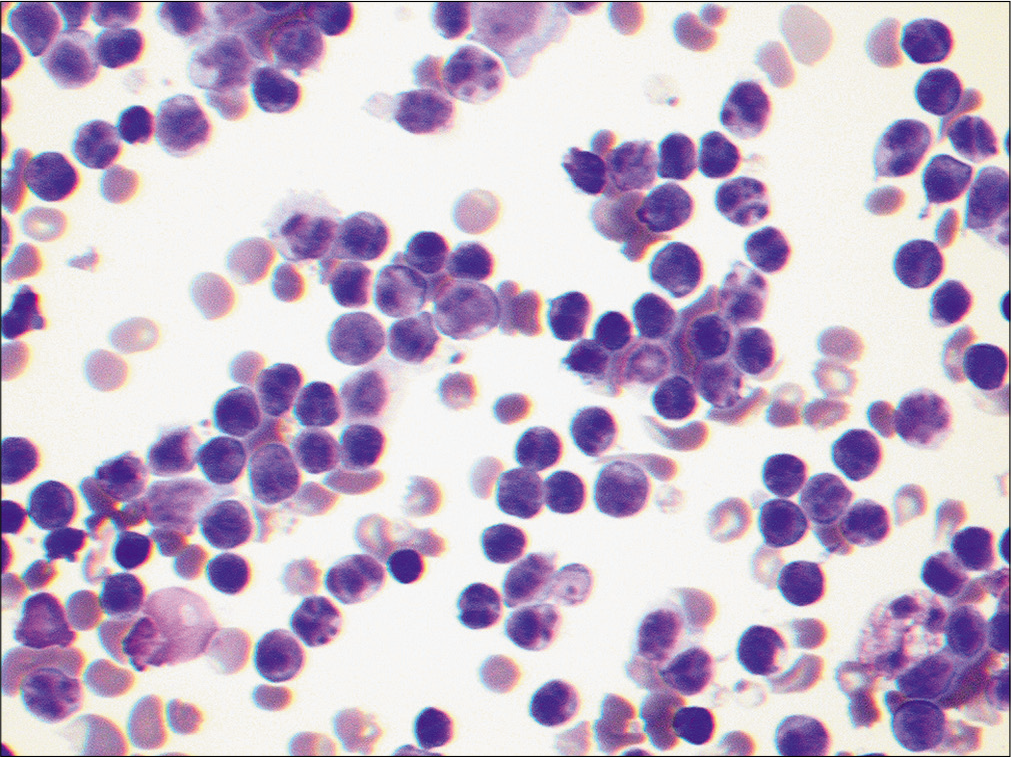

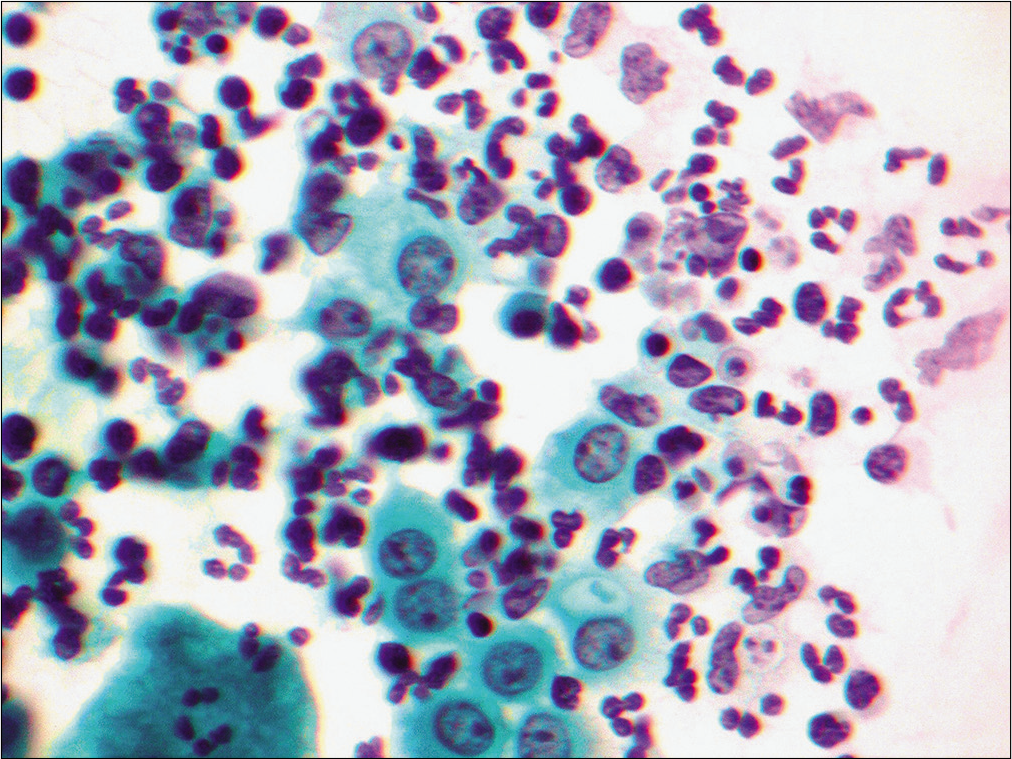

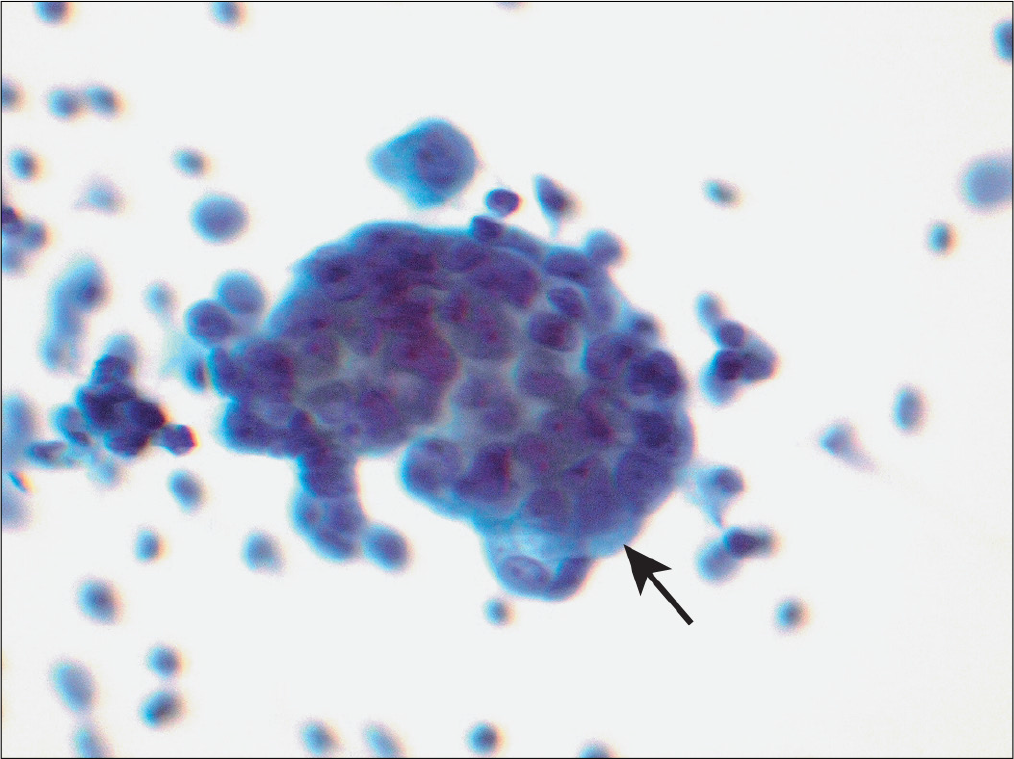

Bacteria [Figures 1-3], parasites (e.g., microfilariae), and fungal forms could be visualized by morphologic examination and may be further highlighted using appropriately selected silver stains, periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain, or other special stains (e.g., Ziehl–Neelsen stain). As a routine stain, the organisms are highlighted better in Diff-Quik stained preparations [Figure 2 (arrow)].

- Many apoptotic neutrophils are noted in the pleural effusion sample from a patient with empyema associated with bacterial infection. (Papanicolaou stain, 20×.)

- In the same patient as Figure 1, the second day pleural effusion sample demonstrated many neutrophils with cocci within the cytoplasm (arrow) better highlighted in Diff-Quik stained preparation. In such patients, bacterial cultures would help to further speciate the bacteria. (Diff-Quik stain, 20×.)

- Pleural effusion sample from the same patient also demonstrated macrophages (arrow) with intracellular cocci. (DiffQuik stain, 40×.)

Cultures

Use of appropriate culture media may help detect bacterial as well as fungal organisms and may further help to speciate the organism and its sensitivity to antimicrobial agents.

IMMUNOLOGIC TESTS

Immunophenotyping (immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry)

Demonstration of a polyclonal population of atypical lymphocytes noted in effusion samples may further help to confirm the reactive nature of lymphocytes.

Immunohistochemistry

A panel of immunohistochemical stains rather than one single immunostain performed on atypical cells in an effusion sample may be of additional help to distinguish reactive mesothelial cells from metastatic epithelial malignancies. Importance of these stains and their applications with the ‘subtractive coordinate immunoreactivity pattern’ (SCIP) approach is discussed in other reviews.[13,14] This is one of the more frequently utilized ancillary studies in serous fluid cytology practice.[10,15-18] Similar studies for microorganisms are also frequently used.

CYTOLOGY

Discussion related to the morphologic details of cells that can be seen in effusion samples is discussed in other reviews.[2,19-21]

REACTIVE CONDITIONS THAT HAVE CHARACTERISTIC FEATURES OF OR COULD MIMIC CARCINOMA

Liver cirrhosis with activity, uremia, and acute pancreatitis

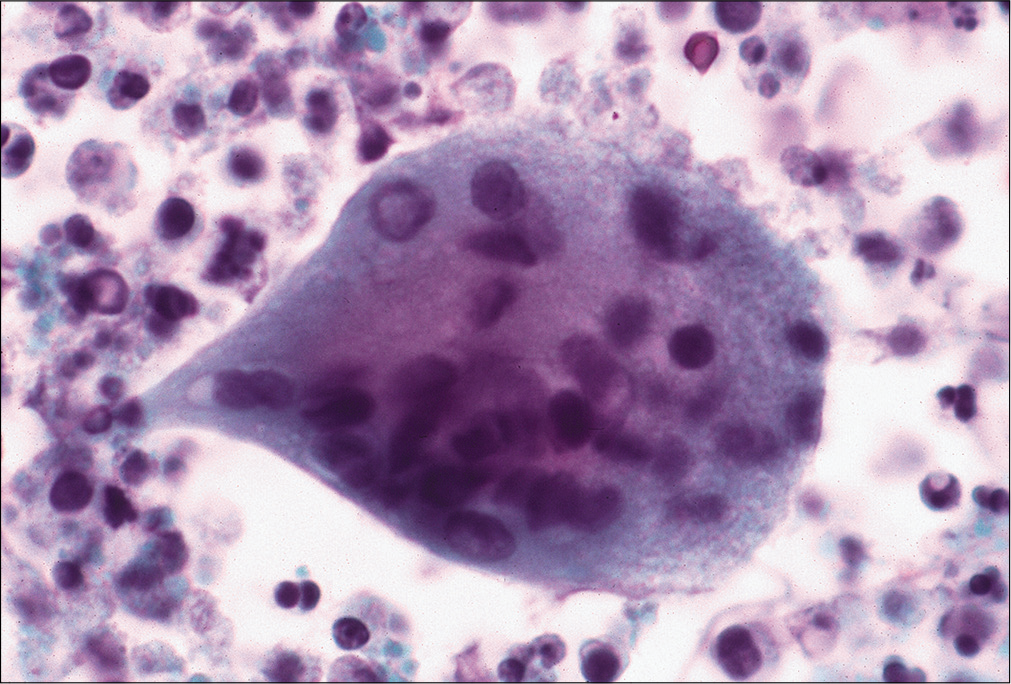

Serous cavity effusions can develop in these conditions and deserve special recognition. In these conditions, reactive mesothelial cells could be present singly, in groups [Figure 4], may form pseudopapillary structures [Figure 5], or may form small gland-like formations. These cells could show extreme degrees of reactive atypia including multinucleation [Figure 6], enlarged nuclei, nuclear membrane irregularities, nuclear hyperchromasia, prominent nucleoli [Figure 7], and mitoses [Figure 8].

- Peritoneal fluid from a patient with cirrhosis demonstrates a group of cells with vacuolated cytoplasm of mesothelial cells. Unlike neoplastic epithelial cells, they do not show a mucin droplet or deform the shape of the nucleus. Chronic inflammatory cells are also noted adjacent to mesothelial cells. (Papanicolaou stain, 40×.)

- Peritoneal fluid from a patient with uremia demonstrates pseudopapillary groups with psammomatous calcification. (Papanicolaou stain, 40×.)

- This pleural effusion sample from a patient with pancreatitis demonstrates multinucleated reactive mesothelial cells. (Diff-Quik stain, 40×.)

- Pleural effusion sample from a patient with uremia demonstrates a flat sheet of reactive mesothelial cells with marked variation in cell size, mesothelial cell ‘windows,’ nuclear enlargement, and prominent nucleoli. (Papanicolaou stain, 40×.)

- Peritoneal fluid sample from a patient with cirrhosis demonstrates occasional mitosis (arrow). (Papanicolaou stain, 20×.)

As a general rule, therefore, a diagnosis of malignancy should be made with extreme caution in patients who have a history of effusions noted in association with the abovementioned etiologies.

In these effusions all atypical cells will show similar features and will resemble mesothelial cells. Thus a ‘morphologic continuum’ and not two distinct cell populations is noted in these conditions. Immunophenotyping may further help in distinguishing reactive mesothelial cells from metastatic adenocarcinoma by the SCIP approach.[13,14]

Pulmonary Embolism and Infarction

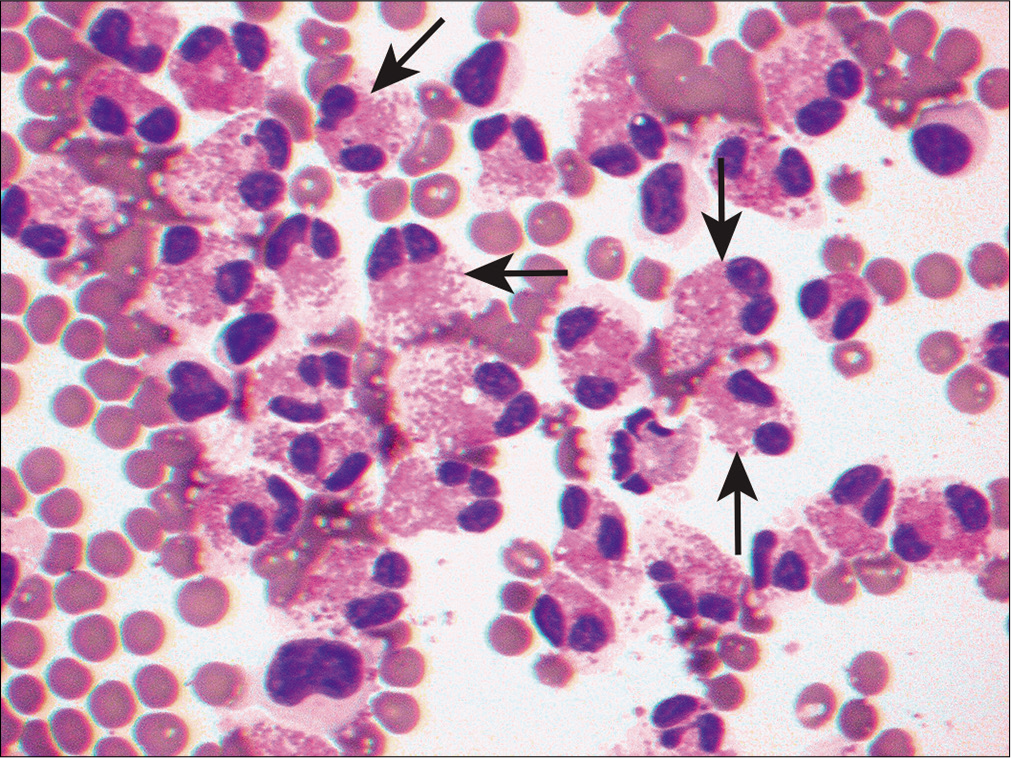

Effusions associated with pulmonary infarction may show reactive mesothelial cells that may require them to be distinguished from adenocarcinoma. These effusions may also show increased hemosiderin-laden macrophages [Figure 9], neutrophils, and eosinophils [Figure 10].

- Pleural effusion from a patient with pulmonary infarction shows macrophages, and some also demonstrate hemosiderin pigment (arrows) in the cytoplasm. (Diff-Quik stain, 40×.)

- Pleural effusion sample from a patient with pulmonary infarction demonstrates areas with increased eosinophils. This example shows characteristic eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules and bilobed nuclei (arrows). (Diff-Quik stain, 20×.)

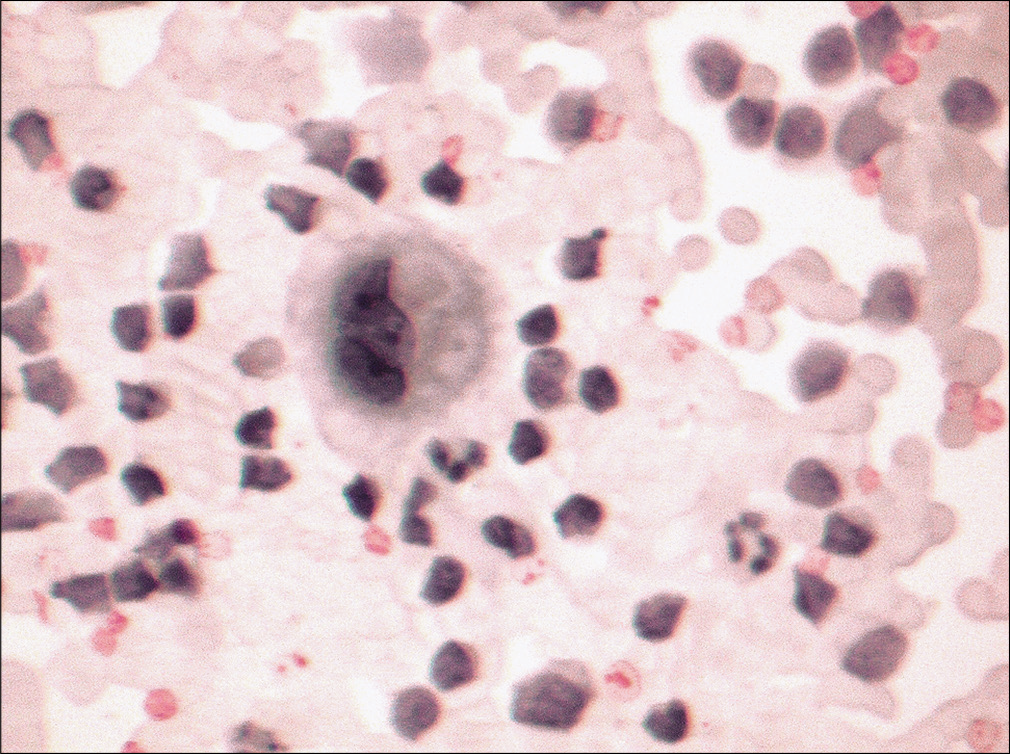

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus[22-24]

Effusions associated with SLE are noted most frequently in the pleural cavity. Although less frequent, SLE-associated effusions may be noted in pericardial cavities. Effusions associated with SLE show characteristics of an exudate. On cytology, these effusions show predominance of inflammatory cells (neutrophils, rarely eosinophils or lymphocytes). One of the most characteristic features is the presence of LE cells. LE cells are inflammatory cells (usually a neutrophil but could be a macrophage) which contain a homogenous hematoxylin body [Figures 11, 12]. The number of LE cells noted in effusion samples can vary. Although the presence of LE cells is a characteristic feature of SLE, it is not pathognomonic of this condition. Other conditions, including drug-associated change, may also show similar features. It should also be recognized that LE cells may not be present consistently in SLE-associated effusions.

- LE bodies (arrow) are noted in a neutrophil in this pleural effusion sample obtained from a patient with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus. (Diff-Quik stain, 40×.)

- LE bodies are seen in both neutrophils (1) as well as a macrophage (2) in pericardial effusion in a patient with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus. (Papanicolaou stain, 40×.)

Rheumatoid Effusions[22-31]

Pleural effusion is a relatively uncommon but known complication of rheumatoid arthritis. It may be concurrent, or occur prior to, or after the development of joint manifestations of the disease. Rheumatoid effusions are exudative fluids and, as noted earlier, are more frequently noted in males with rheumatoid arthritis in comparison to females. These fluids have reduced glucose levels. On cytology, these effusions show many degenerated cells, necrotic debris, atypical spindled cells resembling spindled squamous cells, histiocytes, and round multinucleated giant cells [Figure 13] in addition to many lymphoplasmacytic cells. • It has been suggested that the presence of necrosis in an effusion specimen is almost characteristic of a rheumatoid nodule. Spindled cells may show varying degrees of degeneration and are frequently pyknotic. Spindled cells in these effusions may raise the differential diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma.

- Pleural effusion from a patient with a history of rheumatoid arthritis, lung nodule, and pleural effusion. The effusion sample shows multinucleated giant cells with many chronic inflammatory cells and degenerating as well necrotic cells in the background characteristic of rheumatoid effusion. (Papanicolaou stain, 40×.)

Such characteristic features may not always be seen in these effusions. These effusions may only show increased neutrophils, lymphocytes, and mononuclear cells. Mesothelial cells may either be absent or rare.

Other less-common causes of reactive effusions include fistulous-tract-associated effusions, endometriosis, asbestosexposure-associated effusions, and talc-associated effusions. Correlation with history and corroborative cytologic features are helpful to arrive at a correct interpretation.

STUDY CASES

Case 1

History

A 72-year-old male with a 30 pack-years cigarette smoking history presented with long-standing fever, weight loss, and non-productive cough. This week he noted blood in his sputum and feels he cannot climb two flights of stairs without developing shortness of breath. Imaging studies demonstrated a possible mass in the upper lobe of the right lung, mediastinal adenopathy, as well as a pleural effusion. The pleural effusion was tapped and sent for examination.

Gross examination

A white (milky) odorless fluid (300 mL) was collected. The fluid was turbid and white, even after centrifugation. The effusion triglyceride level was 40 mg/dL.

Biochemical studies

The fluid had a high protein content, with increased effusion: serum lactate dehydrogenase ratio (>0.6).

Cytology

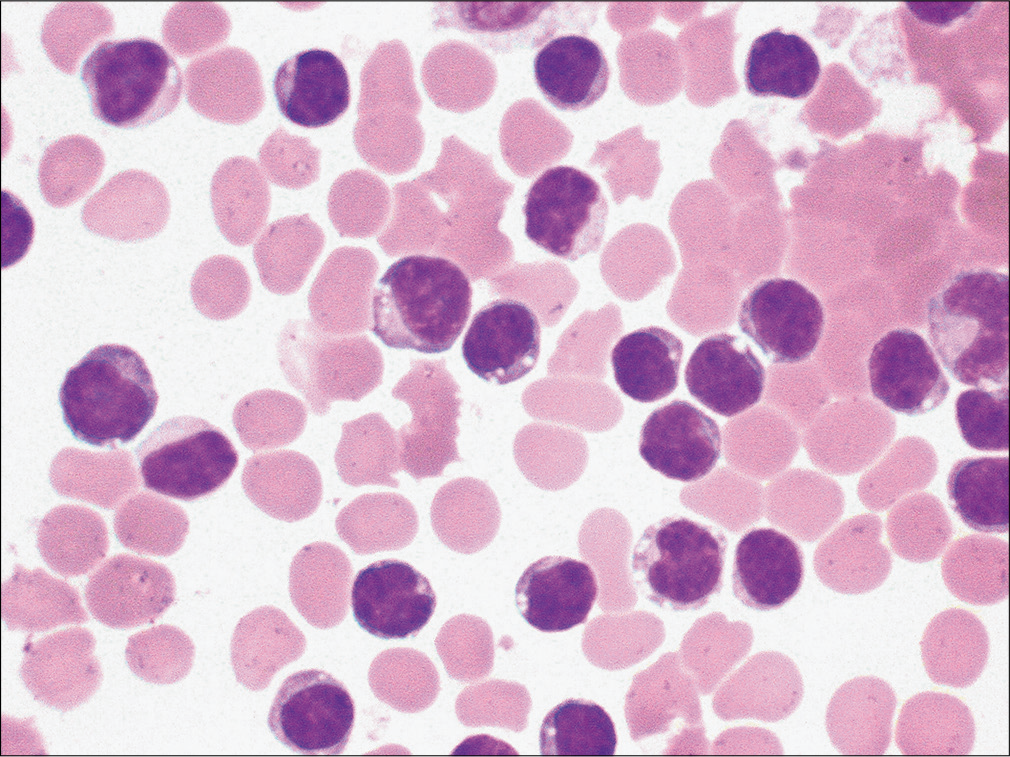

Evaluation of samples demonstrated many mature lymphocytes [Figure 14]. Many lymphocytes also demonstrated marked nuclear membrane irregularity [Figure 15]. Extensive review demonstrated only rare reactive mesothelial cells.

- Many mature lymphocytes are noted in this patient with pleural effusion. (Diff-Quik stain, 40μ.)

- Many mature lymphocytes were noted, with marked membrane irregularity, in this pleural effusion sample. (Papanicolaou stain, 20×.)

Discussion

The history suggests the need for additional studies to begin accurate management. Chief complaints and review of imaging studies suggest that the patient could have a malignancy (especially bronchogenic carcinoma) or an infectious condition (e.g., tuberculosis).

Gross and biochemical examination [Table 5]

| Characteristic | Chylous Effusion | Pseudochylous Effusion |

|---|---|---|

| Effusion Following Centrifugation | Turbid | Turbid |

| Addition of 2ml . ethyl ether | Clear fluid | Turbid Fluid |

| Triglyceride level | ||

| >110 mg/dl | Yes | No |

| 50-110 mg/dl | Presence of chylomicrons | Absence of Chylomicrons |

| <50 mg/dl | No | Possible |

| Effusion : Serum triglyceride | >1.0 | <1.0 |

| Effusion : Serum Cholesterol | <1.0 | >1.0 |

Recovery of a milky and turbid fluid, even after centrifugation, is highly suggestive of pseudochylous fluids. Associated biochemical studies also suggest that this is a pseudochylous effusion.

Cytology

Cytology reveals predominantly small mature lymphocytes [see Figures 14, 15]. Conditions associated with predominant lymphocytes include congestive heart failure, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, tuberculosis, cirrhosis, nephritic syndrome, sarcoidosis, and SLE.

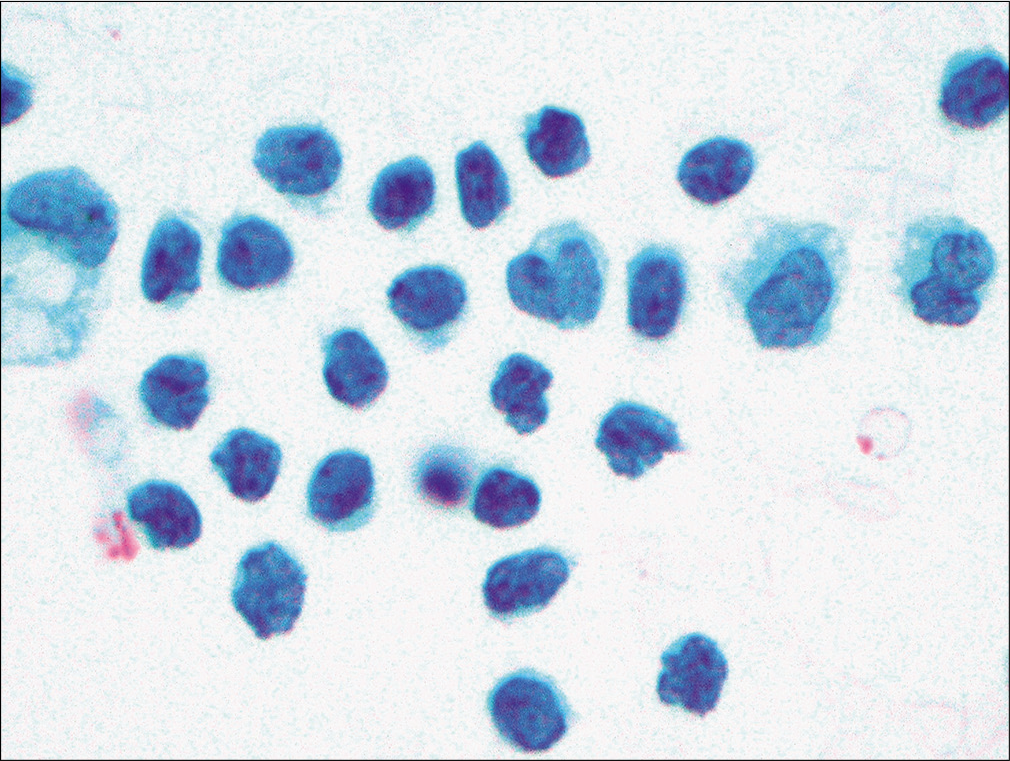

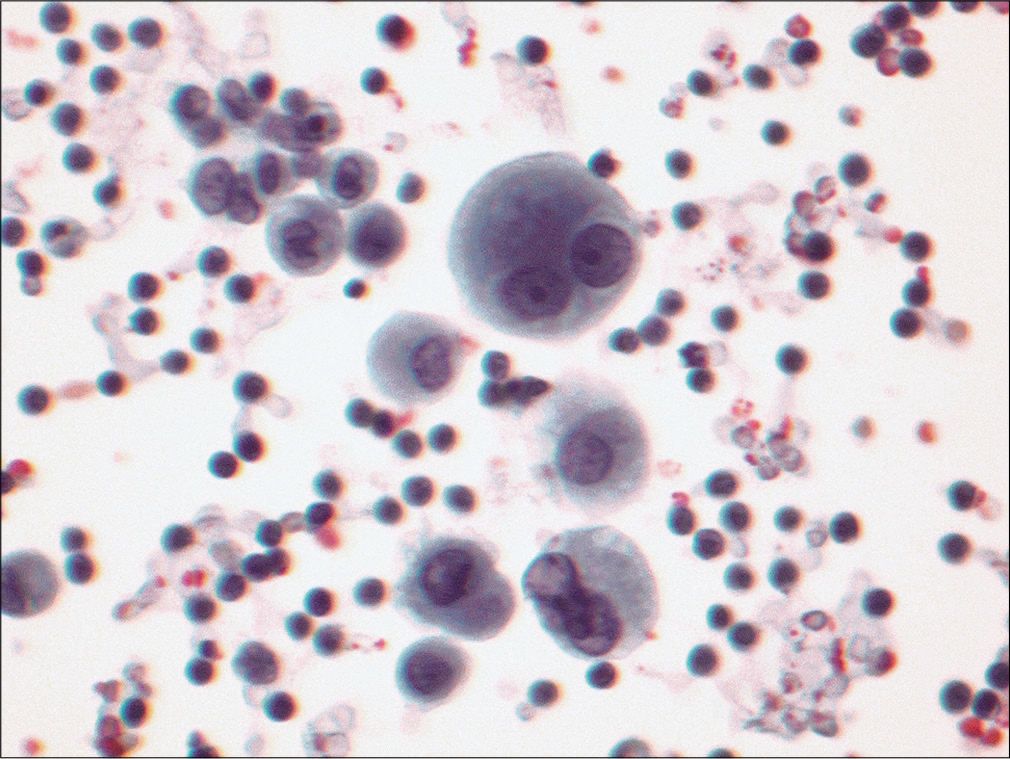

In addition to lymphocytes, only rare mesothelial cells are noted. Lack of mesothelial cells in effusion samples with predominant lymphocytes is characteristically noted in patients with tuberculosis. Cytology samples also shows cells with marked nuclear membrane irregularity. Such cells are most frequently an artifact result of centrifugation. Occasional activated lymphocytes and plasma cells may also be noted. In such a scenario, a possibility of chronic lymphocytic leukemia [Figure 16], primary effusion lymphoma, or a T-cell lymphoproliferative process should be excluded before considering a chronic inflammatory condition as a possibility. Ancillary studies such as immunophenotyping of lymphocytes either using flow cytometry or immunohistochemical studies on cell lock preparations could be useful.

- Many mature lymphocytes are noted in this elderly patient with a history of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. These cells are morphologically indistinguishable from mature lymphocytes noted from other chronic inflammatory conditions. (Diff-Quik stain, 20×.)

Diagnosis

Negative for malignancy; chronic inflammatory cells are noted. A tuberculosis-associated pleural effusion is favored. Additional confirmatory studies are recommended.

Follow-up

The patient had a positive tuberculin test. Transbronchial biopsy was positive for caseating granuloma that demonstrated acid-fast bacilli. Additional studies on an effusion sample revealed adenosine deaminase levels of 50 IU/L. Flow cytometry demonstrated lack of a monoclonal cell population, with increased T lymphocytes.

Tuberculosis[10]

This is one of the more common causes of effusion in countries where tuberculosis is endemic. The diagnosis of tuberculosis should be strongly suspected when a pleural fluid adenosine deaminase level is above 45 IU/L or a g-interferon level is above 3.7 U/mL. In the early stages of the disease, there may be predominantly neutrophils, which in later stages are replaced with mature small lymphocytes. Increased neutrophils with empyema are also noted with miliary tuberculosis.[32] In later stages, patients with tuberculous effusion characteristicallydemonstrate absence of mesothelial cells, even upon repeated thoracocentesis. • Some investigators have therefore suggested that in a suspected patient mesothelial count of greater than 5% in the effusion sample virtually eliminates the possibility of tuberculosis.

Case 2

Clinical history

A 53-year-old male with a history of status post right upper lobe lung resection with adjuvant therapy for non-small-cell lung resection with carcinoma 3 years ago, presented with a pericardial effusion.

Gross appearance and biochemical estimations

A turbid blood-tinged fluid was recovered that demonstrated increased protein content. Lactate dehydrogenase levels were >200 U/L in the effusion sample.

Cytology

The effusion sample demonstrated increased cellularity at lower magnification. This cellularity was a result of many neutrophils [Figure 17], clearly identifiable mesothelial cells, and atypical cell groups. The latter group of cells demonstrated either hobnailing or cells with community borders [Figure 18]. Individual cells demonstrated centrally placed nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli and moderate granular cytoplasm with endoand ectocytoplasm [Figure 19]. In addition, few multinucleated cells [Figure 20] and cells with nuclear hyperchromasia were also identified.

- Pericardial effusion reveals a cellular sample predominantly composed of neutrophils with admixed reactive mesothelial cells. Rare mesothelial cells show cytoplasmic vacuolation. (Papanicolaou stain, 20×.)

- Effusion sample from same patient as in Figure 17 also demonstrates a group of cells (arrow) with three-dimensional organizations with community borders. (Papanicolaou stain, 40×.)

- Effusion sample from the same patient as in Figure 17 also revealed a morphologic continuum, with reactive mesothelial cells demonstrating cells with conspicuous nucleoli, and two-zoned cytoplasm, as would be noted with reactive mesothelial cells. (Papanicolaou stain, 40×.)

- Effusion sample from the same patient also revealed occasional multinucleated cells with cells with cytoplasm showing cytoplasmic vacuolization. (Diff-Quik stain, 40×.)

A diagnosis of atypical cells with possibility of metastatic adenocarcinoma was raised.

Immunophenotype

Immunohistochemical stains performed on the cell block were positive for calretinin and were negative for carcinoembryonic antigen, BerEP4, Leu-M1, cytokeratin 7 and 20, and thyroid transcription factor-1, and supported lack of a second population and confirmed the mesothelial nature of these atypical cells.

Diagnosis

Reactive mesothelial cells: favor therapy-associated changes.

Discussion

A new pericardial effusion in a patient with history of resected non-small-cell carcinoma of lung raises a possibility of metastatic carcinoma.

Evaluation of gross and biochemical estimations suggests this to be an exudate rather than a transudate [Table 6]. An exudate is usually associated with either malignancy or inflammatory/infectious etiology. In this context, this feature does not help distinguish the two.

| Characteristic | Transudate | Exudate |

|---|---|---|

| Gross Appearance | Clear | Turbid |

| Clotting capability | Does not clot | May clot |

| Specific Gravity | Usually 1 or less | >1.0 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase(LDH) | <200u/l | >200u/l |

| Effusion : Serum LDH ratio | <0.6 | >0.6 |

| Effusion/:Serum Protein ratio | <0.5 | >0.5 |

| Cellularity | Usually low | Usually high |

Cytology also reveals a dual cell population with increased neutrophils. In addition, many of the cell groups reveal groups with hobnail appearance as well as occasional groups with community borders. Most of the cells show features associated with mesothelial cells. Table 7 summarizes some of the salient features that distinguish reactive mesothelial cells from metastatic cells. An immunohistochemical staining pattern supports the mesothelial nature of these cells.

| Cytologic Features | Mesothelial Cells | Adenocarcinoma |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Types | Single cell population (spectrum of mesothelial cells) | Dual cell population (mesothelial cells and epithelial cells) |

| Borders of cell groups | Hobnail appearance | Smooth, community borders |

| Intercellular windows | Present | Absent |

| Cell-in-cell pattern | Present | Rare |

| Vauolated cells (signet ring appearance) | Absence of mucin in cells | ‘Mucin droplet’ present |

| Nuclear borders are intact | Vacuole distorts cell nucleus | |

| Cytoplasm | Ecto- and endoplasm could be identified | Usually homogenous |

| Cytoplasmic blebs | Present | Absent |

| Immunohistochemistry | Mesothelial markers +ve | Epithelial markers +ve |

| Microvilli (electron microscopy appearance) | Long and slender | Short and stubby |

Features associated with chemotherapy or radiationtherapy-induced reactive mesothelial cells

With cancer chemotherapy and radiation, there may not be a large effusion but when the effusion samples are evaluated they may present a significant diagnostic challenge for the pathologist. These samples are often cellular, hemorrhagic, and show increased protein concentration. The cellular composition may include highly reactive mesothelial cells with degenerative changes, occasional ‘community’ borders, and cytoplasmic vacuolation. In addition, histiocytes and bizarre cells may also be noted. A clear two-cell population, a cytologic clue to malignancy, is not identified in these samples. In addition, the cells may show features of a radiation therapy effect, including cytomegaly, multinucleation, smudging of chromatin, cytoplasmic vacuolation, and two-toned staining of cytoplasm.

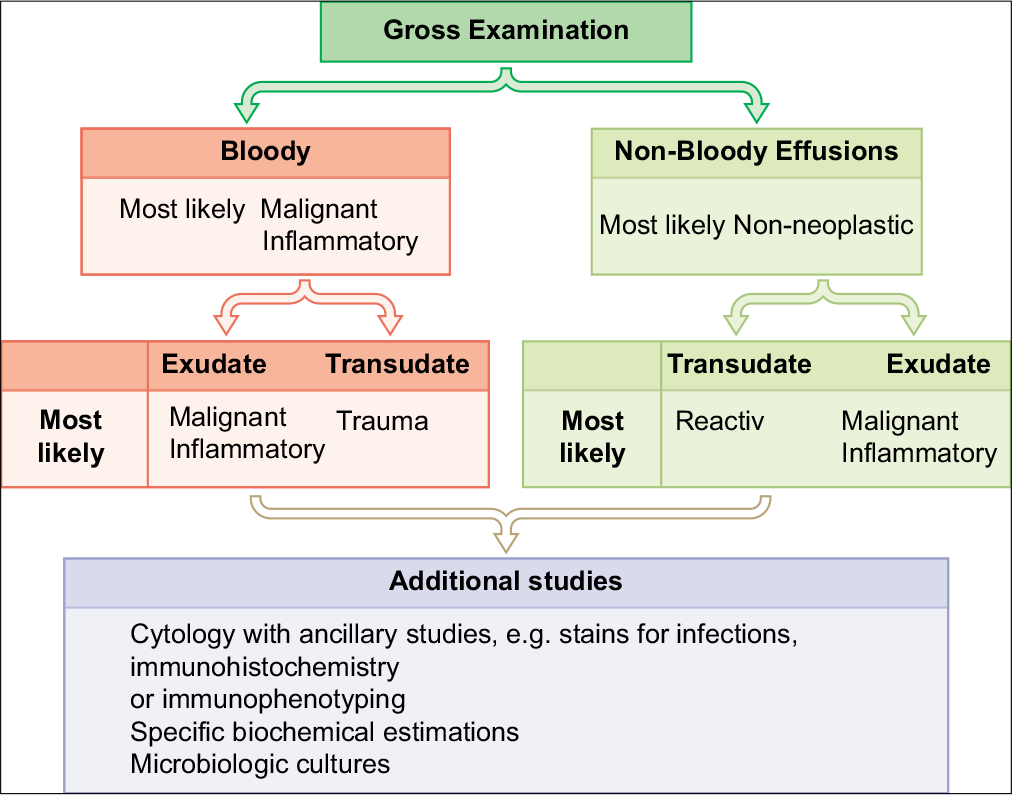

SUMMARY

In summary, this review highlights that a systematic algorithmic approach [Figure 21] would facilitate appropriate processing of effusion samples for improved diagnostic accuracy.[2,19-21] The reporting for cytopathology of serous fluids is comparable to that with other cytopathology specimens.[3,33-35]

- Systemic algorithmic approach to diagnosis.

ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

LE = Lupus erythematosus

PAS = Periodic Acid-Schiff

SCIP = Subtractive Coordinate Immunoreactivity Pattern

SLE = Systemic lupus erythematosus

Acknowledgment

Author of this review and editors of CMAS #2 series thank the initial authors (Nirag C Jhala, MD; Darshana N Jhala, MD, B. Mus; David C Chhieng, MD, MBA, MSHI, MSEM) for all their efforts for the first edition material on which the current review (as chapter #12 in the final CMAS #2) is based under open access charter.

Author thanks Janavi Kolpekwar for copy-editing support.

References

- Diagnostic problems in serous effusions. Diagn Cytopathol. 1998;19:131-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Introduction to the second edition of 'Diagnostic Cytopathology of Serous Fluids' as CytoJournal Monograph (CMAS) in Open Access. CytoJournal. 2021;18:30. HTML of this article is available FREE at:

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collection and processing of effusion fluids for cytopathologic evaluation. CytoJournal. 2022;19:5. HTML of this article is available FREE at:

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical implications of appearance of pleural fluid at thoracentesis. Chest. 2004;125:156-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interpretation of ascitic fluid data. Postgrad Med. 1982;71:171-3, 176-8

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multiple effusions and lymphedema in the yellow nail syndrome. Circulation. 2002;105:E25-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The lipoprotein profile of chylous and nonchylous pleural effusions. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55:700-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Useful tests on the pleural fluid in the management of patients with pleural effusions. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1999;5:245-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biochemical analysis of pleural fluid: what should we measure? Ann Clin Biochem. 2001;38:311-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pneumocystis carinii in pleural fluid. The cytologic appearance. Acta Cytol. 1991;35:761-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunocytochemistry of effusion fluids: Introduction to SCIP approach. CytoJournal. 2022;19:xx. HTML of this article is available FREE at:

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Serous effusions: reactive, benign and malignant In: In Gray and Kocjan, ed (3rd edition). Diagnostic Cytopathology, Elsevier; Chapter 3

- [Google Scholar]

- BerEP4 for differentiating adenocarcinoma from reactive and neoplastic mesothelial cells in serous effusions. Comparison with carcinoembryonic antigen, B72.3 and Leu-M1. Acta Cytol. 1996;40:1212-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Use of a panel of markers in the differential diagnosis of adenocarcinoma and reactive mesothelial cells in fluid cytology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;116:709-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cell-blocks and immunohistochemistry. CytoJournal. 2021;18:2. Available FREE at:

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2021. ISBN Print version 978-1-955571-00-5; e-Version 978-1-955571-01-2 https://www.amazon.com/-/es/Vinod-Shidham-ebook/dp/B098B65PSL This book is available FREE under eCytoJournal at: https://cytojournal.com/eissues/

- [Google Scholar]

- The panorama of different faces of mesothelial cells. CytoJournal. 2021;18:31. HTML of this article is available FREE at:

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Approach to Diagnostic Cytopathology of Serous Effusions. CytoJournal. 2021;18:32. HTML of this article is available FREE at:

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic pitfalls in effusion fluid cytology. CytoJournal. 2021;18:33. HTML of this article is available FREE at:

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eosinophilic pleural effusion with high anti-DNA activity as a manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus. Postgrad Med J. 1980;56:57-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleural effusion in systemic lupus erythematosus. Acta Cytol. 1980;24:553-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus in an elderly male by pericardial fluid cytology: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 1998;18:346-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pericardial effusion in rheumatoid arthritis. Chest. 1973;64:778-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleuritis as a presenting manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis: diagnostic clues in pleural fluid cytology. Am J Med Sci. 2002;323:158-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleural effusion complicating rheumatoid arthritis. Br Med J 1956:428-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleural fluid glucose. Serial observation of its concentration following oral administration of glucose to patients with rheumatoid pleural effusions and malignant effusions. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1968;97:302-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rheumatoid pleural effusions: the case for a primary glucose transport defect. J Rheumatol. 1980;7:110-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- The pathognomonic cytologic picture of rheumatoid pleuritis. The 1989 Maurice Goldblatt Cytology award lecture. Acta Cytol. 1990;34:465-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Miliary tuberculosis as a cause of acute empyema. Respiration. 2003;70:529-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Announcement: The international system for reporting serous fluid cytopathology. Acta Cytol. 2019;63:349-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian academy of cytologists guidelines for collection, preparation, interpretation, and reporting of serous effusion fluid samples. J Cytol. 2020;37:1-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The international system for reporting serous fluid cytopathology-diagnostic categories and clinical management. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2020;9:469-77.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]