Translate this page into:

Cryptococcal infection masquerading as metastatic pleural-based focus

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

To the Editor,

Cryptococcus is an opportunistic fungus that may cause acute infection in immunocompromised patients, in contrast to the mild or asymptomatic infection found in the general population.[1] Cryptococcus neoformans is found worldwide. The yeast is often present in pigeon droppings, contaminated soil, and decaying wood chips.[1] Pulmonary nodules in a patient with previously diagnosed malignancy may be mistaken for metastatic tumor foci clinically. However, an infectious etiology should be kept in the differential diagnosis, especially in cases receiving chemotherapy and in endemic regions such as India. A clinicopathological correlation and tissue or cytology diagnosis of the infectious agent is needed to ensure a proper treatment and favorable outcome in such patients. Here, we report an operated case of cholangiocarcinoma, who presented with a pleural-based nodule which was radiologically interpreted as a metastatic focus.

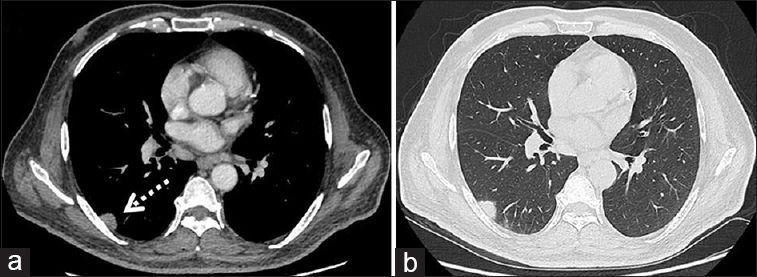

A 56-year-old North Indian male patient, operated 8 months back for distal cholangiocarcinoma, presented with cough without expectoration for 2 weeks, weakness, mild pleuritic chest pain (on and off), and shortness of breath; no fever was documented. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the thorax revealed a well-defined, pleural-based, nodular-enhancing lesion (18 mm × 13 mm) in the right lower lobe, which was seen to abut the right costal pleura [Figure 1]. In lieu of a known malignancy, this lesion was interpreted as a metastatic focus. The patient had undergone a pancreaticoduodenectomy and received six cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy in the form of injection gemcitabine for the primary tumor.

- Axial images from the contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan of the thorax of the patient showing a well-defined, mildly enhancing, soft-tissue lesion abutting the right costal pleura (interrupted arrow in a). Lung window image (b) did not demonstrate any abnormality in the adjoining lung parenchyma

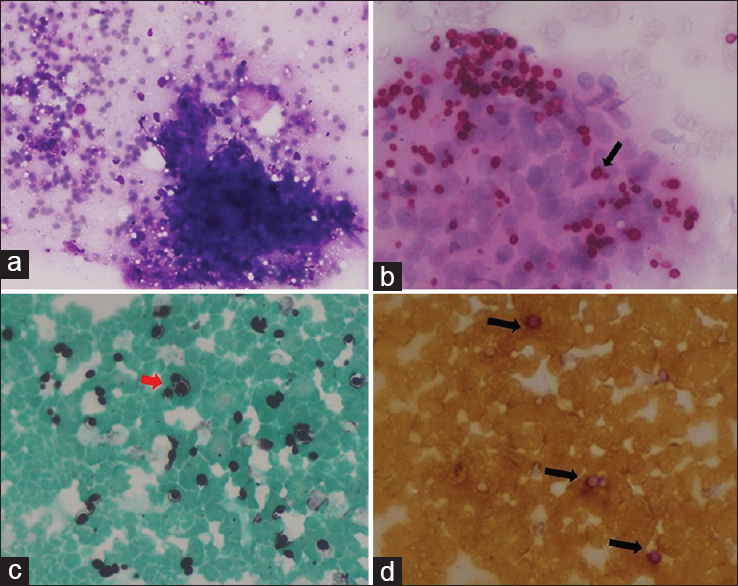

An ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was carried out from this nodule for a definite diagnosis. On cytology, smears were cellular and revealed scattered multinucleate giant cells, stromal fragments, histiocytes, and acute inflammatory cells. In addition, a few refractile negative shadows were identified on routine Giemsa staining, within the giant cells and stromal fragments. Based on these findings a diagnosis of an infective pathology, likely fungal was rendered. Periodic acid–Schiff stain showed numerous intracellular as well as few extracellular yeast forms, which were 5–20 μ in size, capsulated with narrow-based budding. Most of these forms were identified within the giant cells. A Gomori's methenamine silver stain was also performed on one of the smears which demonstrated the budding yeast forms. Mucicarmine stain highlighted the capsule of the fungus as a rose–pink color. Based on the morphology and positivity of the capsule of the fungus for mucicarmine, a diagnosis of cryptococcoma [Figure 2] was given, and the clinically suspected metastatic focus was ruled out. As there was strong clinical suspicion of malignancy, a sample for culture was not obtained during FNA procedure. The patient was started on oral fluconazole therapy (400 mg/day); the lesion resolved completely after 6 months.

- (a) Stromal fragment with negative refractile shadow of fungal spores (Giemsa stain, ×20), (b) yeast forms within a giant cell (PAS, ×40), (c) budding yeast forms (GMS stain, ×40), (d) rose–pink capsule of fungal yeast forms (mucicarmine stain, ×40)

Cryptococcosis is the second most commonly encountered species in pulmonary fungal infections.[2] C. neoformans infection is acquired by inhalation of the organism. Cryptococcus is an opportunistic organism that may cause acute infection in immunocompromised patients.[1] Patients may present with dyspnea and cough, but asymptomatic infections also occur. Fever is often absent in patients with cryptococcal pulmonary disease.[3] In our case, the patient is a known diabetic, who received chemotherapy postsurgery, which increased his susceptibility to such opportunistic infections.

Solitary mass or pleural-based nodular lesions are common findings on chest radiograph, initially suggesting a diagnosis of carcinoma.[4] It is reported that chest CT shows a single nodular shadow in 50%–60% of patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis, spiculation in 30%, and convergence of peripheral vessels and pleural indentation in 50%.[56] In our case also, a solitary nodular pleural-based lesion was seen on CECT. In the setting of a prior malignancy, this lesion was radiologically interpreted as a metastatic focus.

Cytological preparations such as smears or cell blocks offer quick sources of fungal identification. We performed an USG-guided FNA from the subpleural nodule which helped in clinching the diagnosis of an infectious etiology. Pulmonary cryptococcosis has a varied radiologic presentation and is rare in immunocompetent individuals. In a known case of malignancy, pulmonary lesions are often misinterpreted as metastatic foci clinically. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is now widely incorporated in cancer management.[7] Although it is highly sensitive, 18F-FDG is not tissue specific, thus posing diagnostic dilemma in certain situations.[8] False positivity in pulmonary nodules has been seen in various inflammatory conditions.[8] Our patient, however, did not undergo 18F-FDG-PET.

Thus, in endemic regions such as India, it is necessary to carry out a tissue sampling for establishing the diagnosis. FNA cytology offers a rapid and inexpensive means of doing so, thus highlighting the importance of cytology in such cases.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Sunayana Misra (SM)- Preparation of manuscript.

Chhagan Bihari (CB)- Critical review of manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Case report was approved by departmental and institutional review board. Patient consent was duly taken.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

CECT - Contrast enhanced computed tomography

FDG-PET - 18F fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

FNAC - Fine needle aspiration cytology.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (the authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Cryptococcus neoformans. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases (5th ed). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary fungal infection: Emphasis on microbiological spectra, patient outcome, and prognostic factors. Chest. 2001;120:177-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis in the immunocompetent host. Therapy with oral fluconazole: A report of four cases and a review of the literature. Chest. 2000;118

- [Google Scholar]

- Fungal infection mimicking pulmonary malignancy: Clinical and radiological characteristics. Lung. 2013;191:655-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical features and high-resolution CT findings of pulmonary cryptococcosis in non-AIDS patients. Respir Med. 2006;100:807-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis in patients without HIV infection. Chest. 1999;115:734-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis and tuberculoma mimicking primary and metastatic lung cancer in 18F-FDG PET/CT. Nepal Med Coll J. 2011;13:142-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Large cryptococcoma mimicking lung cancer in an HIV-negative, type 2 diabetic patient. J Thorac Imaging. 2005;20:115-7.

- [Google Scholar]