Translate this page into:

Cytomorphologic features distinguishing Bethesda category IV thyroid lesions from parathyroid

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Thyroid follicular cells share similar cytomorphological features with parathyroid. Without a clinical suspicion, the distinction between a thyroid neoplasm and an intrathyroidal parathyroid can be challenging. The aim of this study was to assess the distinguishing cytomorphological features of parathyroid (including intrathyroidal) and Bethesda category IV (Beth-IV) thyroid follicular lesions, which carry a 15%–30% risk of malignancy and are often followed up with surgical resection.

Methods:

A search was performed to identify “parathyroid” diagnoses in parathyroid/thyroid-designated fine-needle aspirations (FNAs) and Beth-IV thyroid FNAs (follicular and Hurthle cell), all with diagnostic confirmation through surgical pathology, immunocytochemical stains, Afirma® analysis, and/or clinical correlation. Unique cytomorphologic features were scored (0-3) or noted as present versus absent. Statistical analysis was performed using R 3.3.1 software.

Results:

We identified five FNA cases with clinical suspicion of parathyroid neoplasm, hyperthyroidism, or thyroid lesion that had an eventual final diagnosis of the parathyroid lesion (all female; age 20–69 years) and 12 Beth-IV diagnoses (11 female, 1 male; age 13–64 years). The following cytomorphologic features are useful distinguishing features (P value): overall pattern (0.001), single cells (0.001), cell size compared to red blood cell (0.01), nuclear irregularity (0.001), presence of nucleoli (0.001), nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio (0.007), and nuclear chromatin quality (0.028).

Conclusions:

There are cytomorphologic features that distinguish Beth-IV thyroid lesions and (intrathyroidal) parathyroid. These features can aid in rendering correct diagnoses and appropriate management.

Keywords

Bethesda category IV

cytology

fine-needle aspiration

parathyroid

thyroid

INTRODUCTION

Thyroid nodules are common in the United States, with reported prevalence between 35% and 65%.[1] Often, these nodules are evaluated by fine-needle aspiration (FNA), which is recognized as the gold standard to evaluate thyroid nodules as it is a minimally invasive procedure that provides an approach for management and assists in determining the correct surgical procedure if necessary.[2345] Unsuspected proliferations, however, may confer a diagnostic challenge. For example, parathyroid glands are located in the neck near the thyroid gland and are sometimes in the thyroid (intrathyroid parathyroid). In one autopsy series, the incidence of ectopic parathyroid glands was reported to be 42.8% with 19.6% in the mediastinum/thymus, 12.5% in the thyroid subcapsular space, and 5.4% in the thyroid parenchyma.[6] Parathyroid cells share similar cytomorphological features with thyroid follicular cells. Three different types of parathyroid epithelial cells may be seen: (1) Chief cells, resembling follicular cells of the thyroid, (2) oxyphil cells, resembling Hurthle cells of the thyroid, and (3) water clear cells, which have clear cytoplasm.[7] The overlapping cytologic features of chief cells and oxyphil cells with follicular and Hurthle cells, respectively, may make it difficult to distinguish parathyroid from thyroid on both cytologic and sometimes histologic specimens. FNAs from thyroid follicular lesions show cells arranged in a microfollicular pattern (6–12 crowded cells in a ring- or rosette-like configuration),[8] a pattern that may also be observed in FNAs of parathyroid tissue.[9] Hurthle cell lesions of the thyroid pose a similar diagnostic dilemma.[10] Similar diagnostic challenge can occur during evaluation of frozen sections, especially when (1) there are oncocyte-rich nodules in the parathyroid, which can mimic Hurthle cell lesions of the thyroid, (2) there is follicle formation by parathyroid glands, simulating a cellular thyroid nodule, or (3) there is fat present in a thyroid nodule, which can mimic parathyroid stroma.[11]

Previous studies have characterized helpful features suggestive of parathyroid, which include the presence of granular or stippled nuclear chromatin, disorganized sheets (which we designate as loose two-dimensional [2D] clusters), three-dimensional (3D) fragments, nuclear overlapping, nuclear molding, anisonucleosis, prominent vascular proliferation with attached epithelial cells, and frequent occurrence of single cells/naked nuclei.[1213] However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the features specifically distinguishing parathyroid from Bethesda category IV (Beth-IV) thyroid lesions, a potential and most likely pitfall given that both are likely to be cellular and have relatively scant colloid/colloid-like material, of the recently implemented Bethesda category terminology. We have noted some overlapping features between the two entities. The aim of this study was to assess the distinguishing cytomorphological features of parathyroid (including intrathyroidal) and Beth-IV thyroid follicular lesions, which may be particularly useful in recognizing unexpected parathyroid tissue and managing patients with “thyroid nodules” that represent intrathyroid parathyroid tissue.

METHODS

Institutional Review Board approval was received for this study. A computerized search was performed from 2006 to 2014, to identify consecutive cases of all “parathyroid” diagnoses in parathyroid and thyroid FNAs and Beth-IV thyroid FNAs (follicular and Hurthle cell), all with diagnostic confirmation through surgical pathology, immunocytochemical stains, Afirma® analysis, and/or clinical correlation. The cytologic slides were prepared with direct smears, using Diff-Quik and Papanicolaou stains, and ThinPrep technique. Cell blocks were prepared on a minority of cases (3 of 5 parathyroid and 4 of 12 Beth-IV thyroid cases). Ancillary studies were performed on cell blocks, and all surgical pathology slides were prepared in a standard fashion from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue and stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain.

All cytologic slides and their corresponding surgical pathology slides were reviewed by two pathologists and scored from 0 to 3 (0 showing the least quantity or quality of the cytomorphologic feature and 3 showing the most) or as present versus absent on the unique cytomorphologic features. The parameters were identified from a literature search[31012141516] and findings from our own observations, which included epithelial cellularity, predominant pattern (flat sheets, 2D, 3D, microfollicles, loose clusters, papillary, single cells), naked nuclei, vascularity, perivascular epithelial cells, cell size, cell shape, nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N:C) ratio, chromatin quality, nuclear contour, anisonucleosis, presence/size of nucleoli, cytoplasmic quality, cytoplasmic vacuoles, cytoplasmic borders, and presence of histiocytes and/or hemosiderin-laden macrophages.

Statistical analysis was performed using R 3.3.1 software. Categorical and continuous variables were assessed using Fisher's exact test and Student's t-test, respectively, using a P < 0.05 for statistical significance. All covariates with P < 0.05 were included in a multiple logistic regression model.

RESULTS

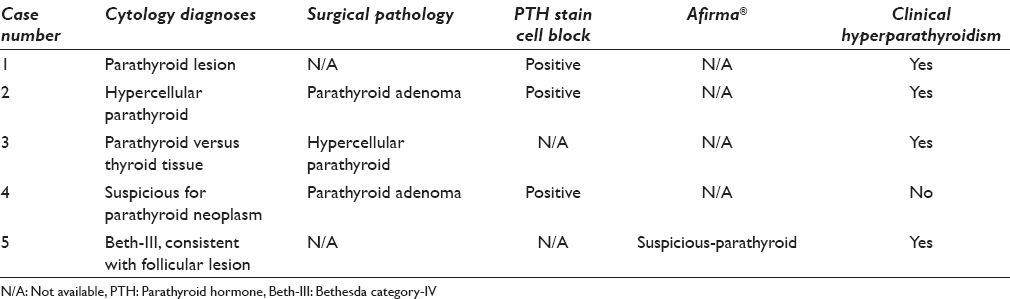

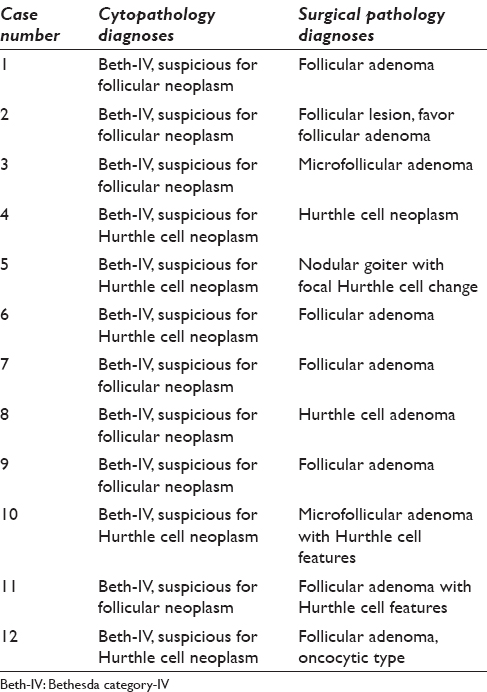

We identified five FNA cases with clinical suspicion of parathyroid or thyroid lesion that had an eventual final diagnosis of the parathyroid lesion (all female; age 20–69 years) and 12 Beth-IV diagnoses (11 female, 1 male; age 13–64 years). Of the five parathyroid cases, 3 were clinically designated as thyroid FNAs, 1 as parathyroid FNA, and 1 as neck nodule FNA. Four of the 5 parathyroid cases had suspected FNA diagnoses of the parathyroid lesion [Table 1]. Three of these cases had surgical resection follow-up. Two resection specimens confirmed the diagnosis of intrathyroidal parathyroid tissue, including one parathyroid adenoma. The third surgically resected case was initially designated as a “neck nodule” and had a clinical suspicion of thyroid versus parathyroid tissue; it was proven to represent parathyroid adenoma. Case #1 without surgical pathology follow-up had positive parathyroid hormone (PTH) immunocytochemical stain. Case #5 was diagnosed as Beth-III, follicular lesion of undetermined significance on FNA; however, Afirma® analysis suggested a parathyroid lesion. This was confirmed by clinically elevated PTH serum level. All 12 Beth-IV cases had surgical resection follow-up, and the results are summarized in Table 2.

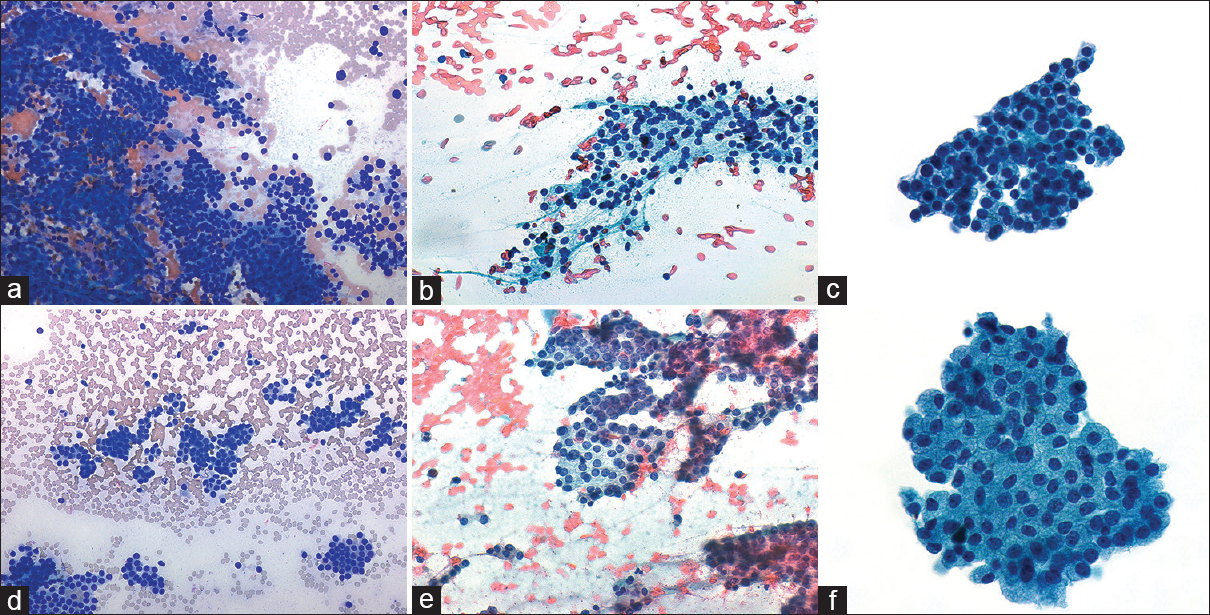

The parathyroid FNAs were moderately cellular with cells arranged predominantly as 2D clusters (i.e., sheets of overlapping cells) and naked nuclei but no single intact cells in the background [Figure 1a and b]. Other patterns observed were flat sheets, 3D clusters, occasional microfollicles, and some papillary structures. Two cases contained some vessels, but these were not a dominant feature. A moderate amount of colloid-like material was observed in 3 of 5 cases. The cells were round with indistinct cytoplasmic borders and scant, delicate cytoplasm. On average, the cells were about 2.4× the size of a red blood cell (RBC). They tended to have high N:C ratio, uniform round nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli, and no cytological atypia [Figure 1c]. The nuclei displayed an even chromatin quality without clumping except one case, which had some stippling.

- (a-c) Parathyroid. (d-f) Bethesda category-IV. (a and d) The predominant architectural patterns: Two-dimensional in (a) parathyroid and microfollicular in (d) Bethesda category-IV (Diff Quik, ×200). Many naked nuclei are present in both (b) parathyroid and (e) Bethesda category-IV but more single cells are observed in Bethesda category-IV (Pap, ×400). (c and f) A higher nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio of (c) parathyroid compared to (f) Bethesda category-IV. Nucleoli and nuclear irregularity are evident in Bethesda category-IV and absent in parathyroid (Pap, ×600)

The 12 Beth-IV FNAs were moderately cellular with cells arranged predominantly as microfollicles, single cells, and some naked nuclei [Figure 1d and e]. The other patterns observed in parathyroid cases were also identified with similar frequencies in the Beth-IV cases. In addition, some loose clusters were also present. Occasional vessels and varying amount of colloid-like material were observed. The cells were round-to-oval and tended to be large, on average about 7× the size of an RBC. They displayed mild epithelial atypia with indistinct cytoplasmic borders and a moderate amount of delicate and sometimes oncocytic cytoplasm. The N:C ratio was low-to-medium. The nuclei showed mild irregularities with stippled chromatin and conspicuous nucleoli [Figure 1f].

The cytomorphologic features associated with parathyroid lesions were assessed in univariate analyses. The useful and statistically significant features are summarized in Table 3. The following features were associated with parathyroid lesion: 2D pattern (P = 0.001), even chromatin quality (P = 0.028), high N:C ratio (P = 0.007), and smaller cell size (2.4× RBC, P = 0.001). The features associated with Beth-IV lesions were: microfollicular pattern (P = 0.001), presence of single cells (P = 0.001), presence of nucleoli (P = 0.001), nuclear irregularities (P = 0.01), stippled chromatin (P = 0.028), and larger cell size (7.25 × RBC on average, P = 0.001). The following features were not significantly different in a univariate analysis: naked nuclei, cellularity, cell shape, anisonucleosis, cytoplasmic borders, presence of histiocytes/hemosiderin-laden macrophages, presence of colloid-like material, presence of vessels/vascularity, papillary architecture, 3D fragments, and nuclear molding/overlap. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed using the seven cytomorphological variables with P < 0.05 in the univariate analysis; no statistically significant associations with lesion type were found.

DISCUSSION

Distinguishing parathyroid (including intrathyroidal) tissue from Beth-IV thyroid follicular lesions has significant clinical implications since Beth-IV lesions carry a 20%–30% risk of malignancy and are often followed up with surgical resection. Parathyroid lesions may present a diagnostic challenge on unsuspected thyroid nodule FNAs. Ultrasound imaging may aid in clinical suspicion, but there are no specific image findings to distinguish parathyroid, thyroid, and lymph nodes, and FNA remains the gold-standard for diagnosing thyroid nodules.[17] Some early literature claimed that parathyroid lesions cannot be reliably distinguished from thyroid lesions on FNA alone.[45181920] Serum PTH level or hypercalcemia can be used for suspicion of hyperparathyroidism; however, it is not useful in cases of nonfunctioning parathyroid lesions.[21] More recent studies have described the varying appearance of parathyroid on cytology and the common diagnostic pitfalls.[12131416] While cytological features of parathyroid tissue FNA have been reported, the criteria specifically distinguishing parathyroid tissue from Beth-IV thyroid lesions have not been previously reported to the best of our knowledge. The most statistically significant distinguishing features were overall pattern, presence of single cells, cell size, nuclear irregularity, nuclear chromatin quality, presence of nucleoli, and N:C ratio.

Cell arrangement and background

Parathyroid FNA specimens typically show intermediate-to-high cellularity with cohesive groups of cells showing 2D[131422] or 3D[12] arrangements. Occasional papillary fragments,[1423] microfollicular arrangements,[2223] and tight clusters[23] may also be observed. The cell clusters have an overlapping appearance with numerous naked nuclei in the background.[12131422] Other described patterns include disorganized sheets[12] (another term for 2D arrangements), prominent vascular network[12131424] with associated epithelial cells, and microfollicles.[1213] Colloid-like material[121322] and macrophages may be present in the background.[1213]

In contrast, Beth-IV thyroid aspirates, which are typically cellular, consist of follicular/Hurthle cells arranged as microfollicles, trabeculae, and syncytia.[225] Crowding and overlapping of cell groups are conspicuous, and the follicular cells are usually larger than normal follicular cells. Colloid is typically scant or absent.

A study by Absher et al. compared the cytological findings of parathyroid FNAs to thyroid lesion FNAs, which included papillary carcinoma, follicular adenoma, adenomatoid nodule, and Hashimoto's thyroiditis.[12] They found that overlapping 3D fragments were more likely to be found in parathyroid whereas flat honeycomb sheets are more common in thyroid aspirates. Papillary fragments and microfollicular arrangements were seen in both types of aspirates. Our study showed similar findings, with 2D sheets representing the statistically significant cell arrangement that distinguishes parathyroid from Beth-IV (based on the images in Absher et al.'s study, the cell groups that we interpret as 2D sheets are quite similar to what they interpreted as 3D groups; for our study, we interpreted 3D architecture as more of a ball of cells as opposed to a cellular sheet with overlapping cells). Similar to the findings of Absher et al., papillary fragments and microfollicular arrangements were present in both our parathyroid and thyroid aspirates, and neither was a statistically significant distinguishing feature.

Although naked nuclei have been described to be more prevalent in parathyroid aspirates,[1213] this feature was seen in both parathyroid and Beth-IV in our study. In addition, we found both background colloid-like material and macrophages in our parathyroid and thyroid aspirates, indicating that have been previously reported.[1213] Well-defined cytoplasmic borders have been described in both parathyroid and thyroid aspirates.[12] This features was variably present in the Beth-IV cases and noted in only 1 of our parathyroid cases; however, we are uncertain whether these rare clusters represented parathyroid versus thyroid. Either way, it was not a statistically significant finding.

Nuclear features

Parathyroid cells demonstrate round-to-oval nuclei, regular nuclear membranes, and inconspicuous or absent nucleoli,[121423] and the chromatin is hyperchromatic, coarsely granular, or stippled.[12131424] Moderate-to-high N:C ratio, anisonucleosis, and nuclear overlapping are other features that may be observed.[12] The follicular cells of follicular thyroid lesions (Beth-IV) are usually larger than normal follicular cells.[25] Nuclear atypia or pleomorphism is typically uncommon but has been described.[26] Nucleoli are generally inconspicuous in parathyroid and infrequent in follicular nodules but may be seen in both.[1327] Compared to oncocytic parathyroid adenoma, Hurthle cell thyroid neoplasms have larger nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and tend to be more discohesive.[28]

Compared to follicular cells, the nuclei of parathyroid cells contain chromatin that is more stippled[14] or hyperchromatic[12] than thyroid follicular cell nuclei, which contain more finely granular chromatin,[12] although cells from follicular nodules (Beth-IV) may have coarse chromatin.[27] The presence of stippled chromatin was not a statistically significant finding in distinguishing parathyroid from Beth-IV. We found nucleoli to be a significant finding in distinguishing parathyroid from Beth-IV cases with all 5 parathyroid FNAs lacking nucleoli and 11 of 12 Beth-IV cases containing nucleoli though they ranged from inconspicuous to prominent. Anisonucleosis, although present in only a small portion of the cells, is a reported feature of parathyroid FNAs[1223] but uncommon in thyroid follicular lesions.[27] Anisonucleosis was minimal to nil in our parathyroid cases and ranged from nil to moderate in the Beth-IV cases although the differences were not statistically significant. Absher et al. described nuclear molding to be a feature that was present in most parathyroid aspirates and rarely seen in thyroid lesions.[12] None of our parathyroid or Beth-IV cases demonstrated cells with nuclear molding.

Cytoplasmic features and cell size

Parathyroid cells are small[121423] with cytoplasm that is usually pale[13] and finely granular.[12132327] Cytoplasmic vacuoles[121327] or oxyphilia may also be observed.[12132327] Well-defined cytoplasmic membranes/borders[1223] have been described in a minority of cases. The cytoplasm of follicular cells in Beth-IV (follicular adenoma) lesions is usually delicately vacuolated or finely granular (follicular lesions) or granular and oncocytic (Hurthle cell lesions).[27]

Compared to follicular cells, parathyroid cells are usually smaller[12131424] and contain less cytoplasm,[1324] although they may contain oxyphilic cytoplasm,[12132327] which can lead to misinterpretation as Hurthle cells. Cells from all 5 of our parathyroid cases demonstrated scant, delicate cytoplasm. While a few cells with more abundant cytoplasm were noted in 3 of our parathyroid cases, none demonstrated the abundant oncocytic cytoplasm that is typical of Beth-IV Hurthle cell lesions. Six of our 12 Beth-IV thyroid FNAs contained cells with delicate cytoplasm. The other 6 contained cells with oncocytic/Hurthle cell features, 5 of which were shown to be follicular adenoma with Hurthle cell features/Hurthle cell adenoma on resection and 1 of which was shown to represent nodular goiter with focal Hurthle cell change on resection. Shidham et al. described the presence of intracytoplasmic fat vacuoles, best seen on Romanowsky stain, in imprint smears from parathyroid gland as being useful in confirming parathyroid tissue.[29] All 5 of our parathyroid specimens and all 12 Beth-IV cases lacked cytoplasmic vacuoles.

The smaller size of parathyroid cells compared to Beth-IV was a significant finding in our study. All 5 of our parathyroid cases showed small cells with high N:C ratio which were 2–3× the size of an RBC compared to the larger cells of Beth-IV cases, which contained cells that were on average 6.95× the size of an RBC.

Ancillary studies

PTH assay and/or immunocytochemical studies[422] performed on FNA specimens may be useful in classifying a nodule as parathyroid origin. In parathyroid aspirates, the PTH level of aspirated fluid (range 248–240,075 pg/mL) and the ratio of PTH in the aspirated fluid to PTH in serum (range 3.67–458.3) are markedly elevated, which may guide in diagnosis.[30] However, in our experience, PTH analysis is not typically performed on thyroid FNAs unless there is prior clinical suspicion for intrathyroidal parathyroid tissue or cytological suspicion of parathyroid at the time of rapid on-site evaluation. Although we occasionally prepare an extra ThinPrep slide or destain a Papanicolaou-stained direct smear for immunocytochemical stain(s), such procedures require sufficient material remaining in the CytoLyt (Hologic Inc., Marlborough, Massachusetts, USA) or the presence of sufficient diagnostic material available for destaining/immunostaining, respectively. Furthermore, immunocytochemical stain performed on a nonformalin-fixed slide tissue requires validation. Immunocytochemical stains in our institution are almost always performed on cell block material, but with the recent implementation of next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis on many Beth-III and Beth-IV thyroid aspirates, cell blocks are typically not prepared on thyroid FNAs. In cases where we suspect that immunocytochemical stains might be more useful than NGS to classify an atypical or suspicious thyroid nodule (e.g., metastatic tumor), we forego possible NGS and have a cell block prepared. Suspicion for intrathyroidal parathyroid tissue may be sufficient reason to have a cell block prepared and omit potential NGS.

This study is limited by small number of parathyroid aspirates. Nonetheless, this correlates with the small percentage (i.e., approximately 5%) of intrathyroidal parathyroids described in the literature. Further, even smaller numbers are likely to represent enlarged parathyroid glands and present clinically or by imaging for FNA.

CONCLUSIONS

Parathyroid and Beth-IV thyroid FNAs share cytomorphological findings and distinguishing them is often difficult on the aspirate material. However, distinguishing cytological features, most notably the lower N:C ratio and more prominent nucleoli in Beth-IV lesions, are seen and can be critical in correctly identifying parathyroid tissue, which can be very challenging, especially when the targeted lesion is intrathyroidal. Additional useful cytological findings separating parathyroid from Beth-IV include overall less nuclear irregularity, a predominant 2D pattern cell arrangement, the presence of single cells, and smaller cell size in parathyroid. These distinguishing cytomorphologic features can aid in rendering correct diagnoses and avoid unnecessary surgery.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and Take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the institution associated with this study (Columbia University Medical Center). Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

FNA - Fine-needle Aspiration

NGS - Next-Generation Sequencing

PTH - Parathyroid Hormone

RBC - Red Blood Cell.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Epidemiology of thyroid nodules. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;22:901-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the management of thyroid nodules. West J Med. 1981;134:198-205.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytopathological variables in parathyroid lesions: A study based on 1,600 cases of hyperparathyroidism. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;16:476-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of parathyroid lesions: A morphological and immunocytochemical approach. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:338-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preoperative localization of enlarged parathyroid glands with ultrasonically guided fine needle aspiration for parathyroid hormone assay. Acta Radiol. 1991;32:403-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parathyroid gland anatomical distribution and relation to anthropometric and demographic parameters: A cadaveric study. Anat Sci Int. 2011;86:204-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histology for Pathologists (3rd ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007.

- Thyroid tumors: Cytomorphology of follicular neoplasms. Diagn Cytopathol. 1991;7:469-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Giant intrathyroid parathyroid adenoma: A preoperative and intraoperative diagnostic challenge. Ear Nose Throat J. 2009;88:E1-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of oxyphilic parathyroid hyperplasia. Cytopathology. 2010;21:135-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intraoperative confirmation of parathyroid tissue during parathyroid exploration: A retrospective evaluation of the frozen section. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:538-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of parathyroid gland and lesions. Cytojournal. 2006;3:6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parathyroid fine-needle aspiration cytology in the evaluation of parathyroid adenoma: Cytologic findings from 53 patients. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:407-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration and intraparathyroid intact parathyroid hormone measurement for reoperative parathyroid surgery. World J Surg. 2004;28:1143-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intrathyroid parathyroid carcinoma with intrathyroidal metastasis to the contralateral lobe: Source of diagnostic and treatment pitfalls. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:1142-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound of thyroid, parathyroid glands and neck lymph nodes. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:2411-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parathyroid adenoma diagnosed as papillary carcinoma of thyroid on needle aspiration smears. Acta Cytol. 1983;27:337-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parathyroid aspiration biopsy under ultrasound guidance in the postoperative hyperparathyroid patient. Radiology. 1985;155:193-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of cystic parathyroid lesions. A cytomorphologic overlap with cystic lesions of the thyroid. Acta Cytol. 1991;35:447-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Large non-functioning parathyroid cysts: Our institutional experience of a rare entity and a possible pitfall in thyroid cytology. Cytopathology. 2015;26:114-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic features of parathyroid fine-needle aspiration on ThinPrep preparations. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122:678-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of parathyroid lesions. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:466-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytopathologist-performed ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of parathyroid lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:327-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- NCI Thyroid FNA State of the Science Conference. The Bethesda System For Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:658-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid cytology and the risk of malignancy in thyroid nodules: Importance of nuclear atypia in indeterminate specimens. Thyroid. 2001;11:271-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Art and Science of Cytopathology (2nd ed). Chicago: American Society for Clinical Pathology; 2012.

- Intrathyroidal oncocytic parathyroid adenoma: A diagnostic pitfall on fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:833-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intraoperative cytology increases the diagnostic accuracy of frozen sections for the confirmation of various tissues in the parathyroid region. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;118:895-902.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parathyroid hormone assay in fine-needle aspirate is useful in differentiating inadvertently sampled parathyroid tissue from thyroid lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:227-31.

- [Google Scholar]