Translate this page into:

Immunocytochemical expression of Ki-67/p16 in normal, atypical, and neoplastic cells in urine cytology using BD SurePath™ as preparation method

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to investigate the expression of Ki-67/p16 in urothelial cells in cytological material.

Materials and Methods:

There were 142 urines including normal controls, anonymous rest urine, controls after treatment for urothelial carcinoma (UC) and newly diagnosed UC. Immunocytochemistry for ki-67/p16 dual staining kit was performed on all specimens.

Results:

Eight high-grade UC and six anonymous specimens showed dual positivity. None of the low-grade UC or the control specimens after treated UC showed dual staining. Fifteen of 84 (17.8%) symptomatic cases were negative for both markers, and 59/84 (70.2%) showed positivity for both but not dual staining. Twenty-seven of 84 cases were positive for either Ki-67 (n = 22) or p16 (n = 5). Normal controls and benign specimens were negative for p16.

Conclusions:

Co-expression of p16/Ki-67 in the same cells was found in 16.6% of the cases. All were high grade, and co-expression seems to have limited practical impact as an additional marker in urine cytology. Any positivity for p16 alone strongly indicates malignancy. Negative p16 accompanied by a positive Ki-67 rate at 5% or more could be considered as an additional marker for further clinical follow-up. Both markers, co-expressed and separate, can give additional information in follow-up patients after treatment for UC.

Keywords

Cytology

immunocytochemistry

Ki-67

p16

urine

urothelial carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Urothelial carcinoma (UC) is the second most common urological cancer and one of the larger cancer forms in Norway with an incidence of 21.5/100,000 for men and 6.4 for women.[1] Urine and bladder washing cytology as well as cystoscopy represents the most important investigation tools both in the primary investigation of possible bladder malignancies and in the follow-up after treatment. The Paris classification system[2] has given us a uniform diagnostic classification system for cytological specimens.

Cytological analysis of voided urine has a high sensitivity in the diagnosis of high-grade tumors, including flat carcinoma in situ, but significantly less sensitivity for the recognition of low-grade papillary tumors.[3456] A common challenge is an atypia in association with benign conditions such as inflammation, lithiasis, and viral and therapy-induced changes. There is a significant morphological overlap that frequently results in an atypical or indeterminate diagnosis and uncertainty regarding subsequent management.

Chromosomal aberrations detected by UroVysion FISH (Abbott Molecular, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA) have a high sensitivity (approximately 90%),[789] but the FISH method is not always available in routine cytology laboratories.

A number of immunocytochemical[1011121314] markers have been tested, but so far none have emerged as an effective adjunct to the morphological evaluation.

Ki-67 is a nuclear antigen present in all cycling human cells but not in G0 and is a marker of active cell proliferation.[15] Immunostaining of Ki-67 provides an index that serves to estimate the growth fraction of a population of cells and is used in a number of tumor classification systems as an indicator of tumor aggressiveness.

P16INK4a is a tumor suppressor gene that controls cell cycle progression. Loss of heterozygosity of CDKN2A occurs in around 40% of UC.[1617] Increased levels of p16 can be visualized immunocytochemically and is observed in up to 80%–90% of high-grade UC (HGUC) and 35%–50% of low-grade UC (LGUC).[1213]

In cytology, we may use different fixatives, single or combined. Further, we may use different immunocytochemistry (ICC) methods, different buffers, and pH optimums. All of these may affect our antigen epitopes and thus the antigenicity. ThinPrep PreservCyt™ (Hologic Ltd., Manchester, UK) and BD SurePath™ (Becton, Dickinson Ltd., Wokingham, UK) are two major commercial fixative solutions that are used in the cytology community.

The principle aim of this study was to investigate the usefulness of the dual p16/Ki-67 kit[18] as an adjunct in the diagnosis of atypical, suspicious, and malignant urine cytology samples using BD SurePath as a fixative.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The material consisted of urine and bladder washing samples. The clinical samples were collected from patients at the Department of Urology, Akershus University Hospital. Normal control urine was sampled from healthy biomedical students. All included samples were fixed and processed as liquid-based cytology (LBC). Anonymous rest urine was provided from three outside cytology laboratories and represented patients whose urine samples were cytologically assessed as suspicious for malignancy or malignant (n = 31). These were originally collected to test the method before examining the clinical material. They are anonymous and we have no clinical or histological follow-up on these. They are presented as an indication of what might be expected in the work-up of symptomatic patients in the clinic. The complete material consisted of 142 urine and bladder washing samples [Tables 1 and 2].

| Primary diagnostics | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| Normal controls | 33 |

| PUNLUMP | 5 |

| LGUC | 8 |

| HGUC | 18 |

| CIS | 1 |

| Benign | 4 |

| Anonymous* | 31 |

| Total number of primary cases | 121 |

*From three collaborating cytology laboratories representing anonymous rest material from urine samples diagnosed as suspicious for malignancy or malignant. PUNLUMP: Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low-grade malignancy potential, LGUC: Low-grade urothelial carcinoma, HGUC: High-grade urothelial carcinoma, CIS: Carcinoma in situ

| Follow-up samples after treated UC | Numbers of cases |

|---|---|

| PUNLUMP | 1 |

| LGUC | 5 |

| HGUC | 12 |

| CIS | 3 |

| Total number of posttreatment samples | 21 |

PUNLUMP: Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low-grade malignancy potential, LGUC: Low-grade urothelial carcinoma, HGUC: High-grade urothelial carcinoma, CIS: Carcinoma in situ, UC: Urothelial carcinoma

Sample preparation: All urines from normal controls, control specimens and anonymous rest urines were primarily fixed 1:1 with 50% ethanol and afterwards transferred to SurePath containers. The BD SurePath liquid contains ethanol (15%–20%), <1% isopropyl alcohol, <1% methanol, and approximately 0.1% formaldehyde (BD, Becton Dickinson Ltd., UK).

Bladder washings (approximately 150 ml rinsing fluid) were collected during investigation or transurethral resection of the bladder lesion. If a sample could not be prepared the same day, it was primarily fixed as routine urine samples (1:1 with 50% ethanol).

A prior study investigating the possible effect of the formalin in SurePath[19] in ICC concluded that the antigenicity in the cells was significantly reduced after 5 days. Thus, all samples were stored in SurePath for a maximum of 1 day prior to the slide preparation.

All samples were centrifuged, and the cell compartment was transferred to a SurePath container. A cytospin was prepared the next day (Cytospin, ThermoFisher.com). The slides were stored at −70°C until ICC was done. The samples were collected from January to August 2016.

Immunostaining with the CINtec® PLUS Cytology Kit (REF 605-100, Roche Diagnostics GmBH, Mannheim, Germany) was done according to the manufacturer's protocol which is adapted to samples stored in fluid containing some amount of formalin. The analytical protocol, SurePath CINtec Plus, was run on the Ventana BenchMark XT, IHC/ISH (immunohistochemistry/in situ hybridization) staining module. The protocol[20] involves a heat-induced epitope retrieval, a pretreatment to break up chemical cross-links caused by formalin fixation.

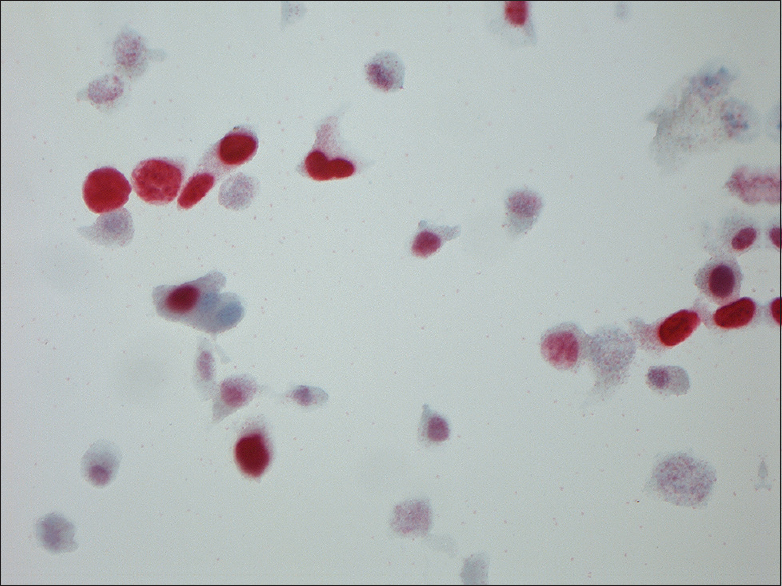

The CINtec® PLUS Cytology Kit (Roche) is an immunocytochemical dual color method for cell markers p16 and Ki-67. The kit contains a ready-to-use antibody cocktail (Lot No. F07342-F07348), with mouse monoclonal antibody directed to human p16INK4a protein and rabbit monoclonal antibody directed against human Ki-67 protein. The secondary step consisted of a polymeric reagent conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and goat anti-mouse fragment antigen-binding Fab fragments (brown color) and a polymeric reagent conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (AP) (red color) and goat anticancer Fab antibody fragments. The two epitopes were visualized by the enzyme HRP indirectly converting the 3,30 diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen and the enzyme AP indirectly converting the chromogen to brown (p16, cytoplasmic and nuclear) and red color (Ki-67 nuclear), respectively, to the binding sites of the p16 INK4a and the Ki-67 antigen. Hematoxylin was used as counterstain.

EVALUATION OF ICC

Evaluation of positivity: All samples with at least one cell being positive for p16 and/or Ki-67 were recorded as positive. Co-expression (dual expression) (i.e., positivity for both markers in the same cell) was recorded. Quantitation of positive cells: 200 urothelial cells were counted, and the proportion of positive cells for each marker was recorded. Twenty-five cases were counted by two observers (KMØ and TS) for intra-observer variation.

Statistical analysis

The counting results, negative coloring, or percentage positive staining with p16 and/or Ki-67 were added to “Statistical Package for the Social Sciences” (SPSS) version 24 (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation New Orchard Road Armonk, NY 10504, USA). Diagnostic accuracy, receiver operating characteristic analysis, sensitivity, and specificity were investigated.

RESULTS

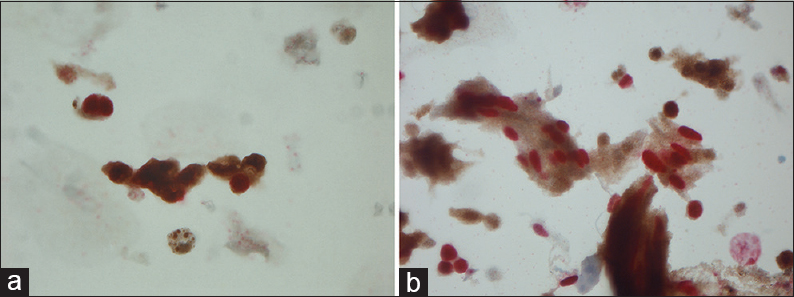

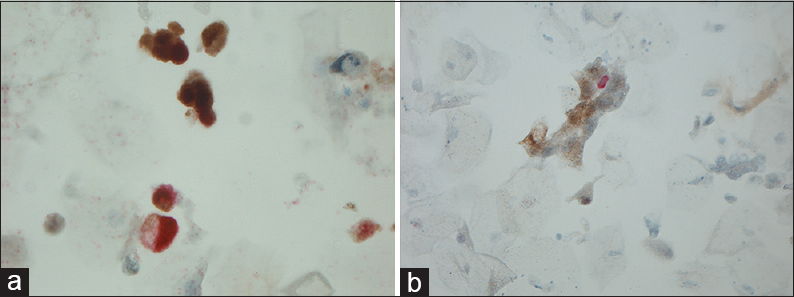

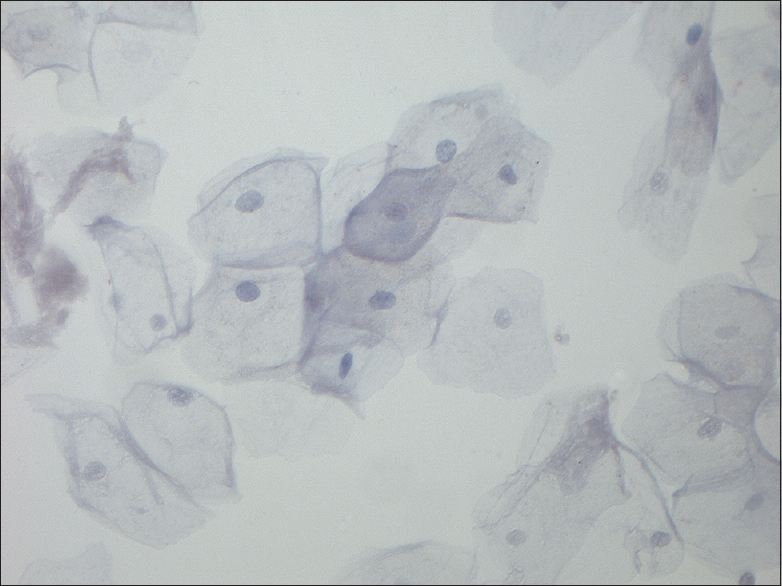

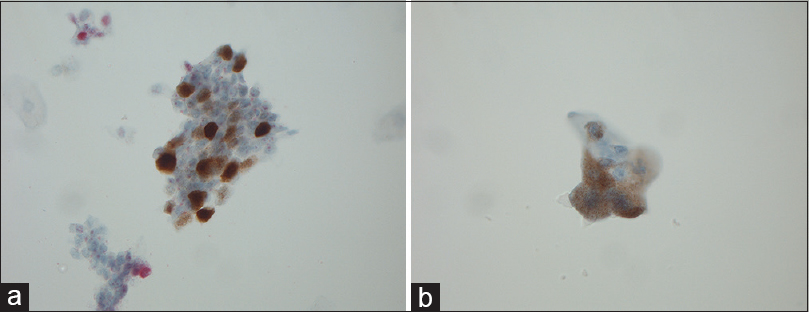

An overview of the ICC results is given in Table 3. Mean, median, minimum, and maximum values of p16 and Ki-67 are seen in Table 4. Positivity for one or both markers was common (71/84 = 84.5%). Dual staining was found in 16.6% (8 in the study group and 6 of the anonymous samples) [Figure 1] of the cases, which accounts for 44% of the known HGUCs. Dual staining was not seen in any LGUC slide or in control slides after treated UC. Fifty-nine of 84 (70.2%) symptomatic samples were positive for both markers (double staining) but not in the same cells [Figure 2]. The normal controls [Figure 3] were completely negative for both markers, whereas 27/84 (32.1%) samples were positive for either p16 (n = 5) or Ki-67 (n = 22) [Figures 4 and 5].

| Tumor type, primary diagnosis | p16 positive | p16 Negative | Ki-67 positive | Ki-67 Negative | Dual p16/Ki67 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 PUNLUMP | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 LGUC | 6 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| 18 HGUC | 13 | 5 | 16 | 2 | 8 |

| 1 CIS | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Controls after treatment | |||||

| 1 PUNLUMP | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 LGUC | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| 12 HGUC | 8 | 4 | 11 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 CIS | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 31 Anonymous | 15 | 16 | 22 | 9 | 6 |

PUNLUMP: Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low-grade malignancy potential, LGUC: Low-grade urothelial carcinoma, HGUC: High-grade urothelial carcinoma, CIS: Carcinoma in situ

| Diagnoses | n | Minimum values | Maximum values | Mean percentage | Median percentage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p16 | Ki-67 | p16 | Ki-67 | p16 | Ki-67 | p16 | Ki-67 | ||

| PUNLUMP | 5 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 7 | 1,8 | 1.6 | 1 | 0 |

| Control after PUNLUMP | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| LGUC | 8 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 10.5 | 4,8 | 3 | 0.75 | 2 |

| Control after LGUC | 5 | 0 | 0 | 12.6 | 5 | 3.7 | 1.6 | 2 | 1 |

| HGUC | 18 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 58 | 8.8 | 13.2 | 1.6 | 8.8 |

| Control after HGUC | 12 | 0 | 0.5 | 26 | 5 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 1.25 | 2.5 |

| Anonymous | 31 | 0 | 0 | 45 | 90 | 4.8 | 16.4 | 0 | 5 |

| CIS | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Control after CIS | 3 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 7.5 | 4 | 3.3 | 4 | 2.5 |

| Normal | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Benign NOS | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.5 | 0 | 2.1 | 0 | 2.5 |

PUNLUMP: Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low-grade malignancy potential, LGUC: Low-grade urothelial carcinoma, HGUC: High-grade urothelial carcinoma, CIS: Carcinoma in situ, NOS: Not otherwise specified

- (a) Magnification, ×630. Dual staining of malignant urothelial cells: Ki-67 (nuclear red) and p16 (cytoplasmic and nuclear brown). (b) Magnification ×630. Dual staining of malignant urothelial cells: Ki-67 (nuclear red) and p16 (cytoplasmic and nuclear brown)

- (a) Magnification, ×630. Positivity for both Ki-67 (red) and p16 (brown: nuclear and cytoplasmic) but not in the same cells. (b) Magnification, ×200. Positivity for both Ki-67 (red) and p16 (cytoplasmic) but not in the same cells

- Magnification, ×400. Normal control

- (a) Magnification, ×630. P16-positive urothelial cells with nuclear staining. (b) Magnification, ×630. P16-positive urothelial cells with cytoplasmic staining

- Magnification, ×630. Ki-67-positive urothelial cells

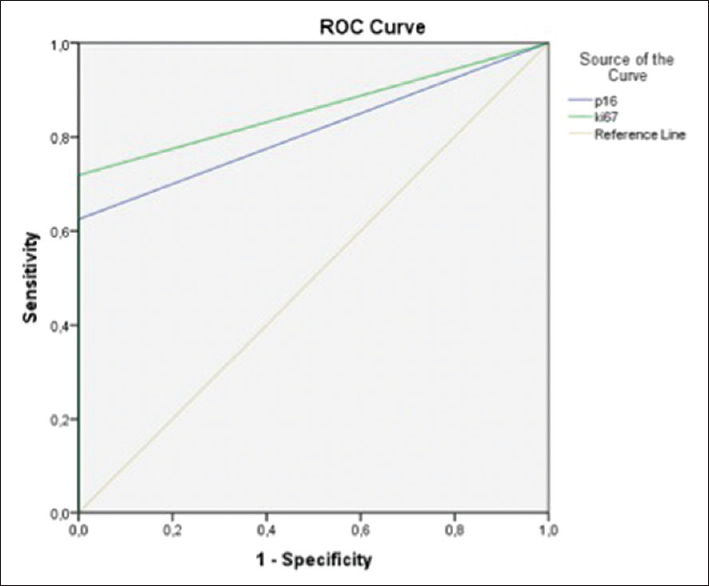

The percentage of p16 positive cells was highest in HGUC, up to 63%. The mean and median values of LGUC and HGUC were 4.8%/0.75% and 8.8%/1.6%, respectively. Fifteen of 21 (71%) and 18/21 (86%) posttreatment samples were positive for p16 and Ki-67, respectively. None of these have so far been diagnosed with residual tumor during the follow-up period which was 1 year after the study was finished. By choosing a Ki-67 cutoff of 5% (regardless of p16 value), all the histologically verified benign lesions fell below this value and the malignant above [Figure 6]. A cutoff of 5% for Ki-67 gave a sensitivity of 42% and a specificity of 100%.

- Receiver operating characteristic curve showing the basis for cutoff for p16 and Ki-67. A cutoff of approximately 5% for Ki-67 gives a sensitivity of 42%. The specificity is 100%

DISCUSSION

Follow-up routines for bladder cancer patients consist of regular cystoscopy and cytological examination of urine. Low-grade lesions are the most difficult to detect. This is partly due to reactive and degenerative changes in the urothelial cell, either as a direct consequence of intravesical treatment (Bacille Calmette Guérin [BCG]) or due to radiation damage in both benign and malignant cells, as well as reactive and reparative changes. About half of all bladder cancer patients experience recurrence, and there is a great need for effective and gentle methods in the follow-up of patients.[2122] Increased sensitivity and safer noninvasive diagnostic methods may reduce the need for cystoscopy.

We wanted to investigate whether immunocytochemical detection of p16 and Ki-67 in urine samples could improve sensitivity and specificity in urinary cytology. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that BD SurePath had been used in the ICC of urinary samples. Examples of our ICC results can be seen in Figures 1 and 5.

Co-expression (“dual positivity”) was an unusual event in our material and was found only in 16.6% of the clinical lesions. These had obvious malignant (high grade) morphology. Therefore, in contrast to cervical cytology, co-positivity has no practical value in urinary cytology. This is in accordance with the findings of Piaton et al.[2324] They found that p16/Ki-67 staining had a high sensitivity to high-grade UC, but that it did not have significantly higher sensitivity than conventional urinary cytology. In their material, 16% of LGUC/PUNLMP (low grade urothelial carcinoma/papillary urothelial neoplasm of low grade malignant potential) were co-positive, whereas 76% were positive for p16 alone. In a follow-up study, the same group found that the sensitivity of positive p16/Ki-67 double staining and life-threatening cancer disease was 83.6% and 82.2% for cytology alone. In the case of negative cytology, disease-free survival was significantly shorter with concomitant ICC positivity as compared to ICC-negative cases.[1324]

Some studies have investigated the ICC expression of p16 alone in urinary malignant cells. Alameda et al.[10] indicates that p16 ICC expression could increase sensitivity and specificity of carcinoma diagnosis in urine samples. The group found that 66.3% (55 of 83 with atypia) expressed p16 positivity. Thirty-six of the 55 had a positive biopsy. Nakazawa et al.[12] found that 80% of HGUCs and 50% low grade were positive for p16.

In the primary diagnosis, the HGUC cells are morphologically well recognizable, and additional methods are not necessary. LGUCs have a very discreet cellular atypia and are difficult to acknowledge morphologically. In clinically suspicious cases, p16 would be able to detect many of these in primary diagnosis (in our material, 75% of the low grades were positive for p16). In patients treated for UC, irregular cells of uncertain significance (atypia) may be found. These may represent degenerative or reactive changes or malignant cells with secondary changes. These represent a major diagnostic challenge morphologically. In equivocal cases, positivity for p16 may be suspicious of recurrence. The anonymous samples in our material showed positivity of p16 in 43.8%, which is on the same level as the primary diagnosed carcinomas. We have no follow-up on these, but the results indicate that a substantial number of these were from high-grade malignant lesions. None of the benign samples were positive for p16, indicating that p16 positivity, regardless of the number of positive cells, would be a strong indication that the cells might be malignant and that cystoscopy should be done for further investigation.

Ki-67 is a proliferation marker showing an increased proportion of positive cells in malignant lesions, but also showing increased expression in repair of cell damage. Benign changes usually have low Ki-67 values. In our benign samples, the highest value was 3.5%. During BCG treatment, there is a significant reparative response that represents an active proliferation of cells, and thus, we would expect an increased expression of Ki-67. The material contains only one such sample, and it had 4% Ki-67-positive cells. According to our findings, a proportion of Ki-67-positive cells of 5% could indicate malignancy and possibly recurrence in cases of previously treated UC. With a cutoff of 5%, we would have a sensitivity of 42% and a specificity of 100% [Figure 6].

Courtade-Saïdi et al.[14] tested dual ICC in urinary cytology for p53 and Ki67 as possible adjunct markers in the detection of UC. P53, like p16, is a cell cycle regulating tumor suppressor protein. Overexpression is associated with higher tumor grades and stages, disease progression, and decreased survival.[1422] The optimal cutoff for detection of all types of UC, taken as a whole, was calculated at 5% for p53 and 3% for Ki-67. This gave the highest specificity of 97.6%, while the sensitivity dropped to 68.9%. This is a better result than reported for UroVysion FISH (Abbott Molecular, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA)[78925] or p16/Ki-67 dual staining,[13] including our results. They conclude that testing for p53 and/or Ki-67 increases the specificity without reducing the sensitivity.[1424]

The studies cited used different methods of preparation and fixation, which may explain some of the different results compared to our study. In cytology, we use different fixatives. Ethanol is the most common fixation method. Special investigations such as in situ hybridization and ICC often use other fixatives such as acetone or methanol, possibly sequencing with several different fixatives. Acetone is considered to be the most sensitive fixative but often gives some unspecific background staining. It is used in fluorescence ISH (FISH) where unspecified background is a minor problem. It is also known that methanol provides better immunoreactivity than ethanol.[262728] Formalin is little used for fixation of cytological material but may be of value as postfixation.[29] SurePath contains a small amount of formalin. In a previous small pilot study,[19] we found that the immunoreactivity was reduced after 5 days of storage in the SurePath liquid. Cells suspended in SurePath should, therefore, optimally be prepared with a few days in order to avoid significant epitope masking by formalin.

Both Piaton et al.[13] and Courtade-Saïdi et al.[14] used 50% ethanol as primary fixation as was done in our study. Piaton et al. then used methanol (ThinPrep PreservCyt) as secondary fixation. Courtade-Saïdi et al. used acetone as a secondary fixation, whereas we used ethanol/formalin (BD SurePath). Alameda et al. fixed primarily in methanol without secondary fixation. In addition, different pretreatment and different ICC protocols can contribute to different results. Although we knew that methanol could be better suited for ICC, we wanted to test SurePath because an increasing number of cytology laboratories in Norway use this as a routine method for preparation of both cervical and nongynecological specimens.

It is possible to use both cytological preparations (cytospin, LBC preparations) and cellblock for ICC examinations. Cellblock is the preferred method in many institutions because histological protocols can be applied. It is then common to use histological material as a positive control. In urinary samples, there are usually limited amounts of cells, and it is difficult to make cellblocks even with automation. However, there will usually be enough material to make 1 or 2 additional preparations in addition to Pap-stained routine preparations. ICC protocols will differ from that used for histological material and must be tested and optimized. Positive control material can be a challenge. Liquid-based material from verified carcinomas often contains abundant tumor cells. These can be prepared and used as positive control samples. Cytological preparations can be frozen and stored for a long time. Sauer et al. have shown that long-term storage of liquid-based preparations at −20°C or −74°C for at least 6 months does not significantly reduce immunoreactivity.[30]

CONCLUSIONS

Dual positivity of p16/Ki-67 was only detected in 16.6% of the clinical cases, all of which were morphologically high-grade malignant. Dual expression thus has no practical significance as an additional marker. Positivity of p16 alone is a strong indication of malignancy or risk of recurrence and thus an indication for follow-up and eventually cystoscopy. Likewise, negative p16 with Ki-67 expression >5% could be a malignancy indicator. Both markers, together and separately, may provide additional diagnostic information in urine cytology.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The basis of this article was the master thesis of KM Østbye. The thesis originates from the Oslo Metropolitan University (Oslo, Norway) and was published in Norwegian in 2017. The thesis was rewritten as a research article in English for international publication in Cytojournal.

Apart from the above all three authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Mette Kristin Pedersen has done the initial laboratory handling and has prepared all the Surepath slides.

Kirsten Margrethe Østbye has done the immunocytochemistry, the microscopical evaluation and has been the main writer of the manuscript.

Torill Sauer was scientific supervisor and has assisted in all scientific aspects of the project, including discussions of results and writing.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The project was approved by the regional ethics committee (REK), Norway with the document number 2014/912. The project was approved by the institutional review board at Ahus with the document number 14-128. There are no ethical issues in the project, and it has been done according to the REK requirements by all three authors.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

Ahus – Akershus University Hospital

BCG – Bacille Calmette Guerin

DAB – Diaminobenzidine

FISH – Fluorescens in situ hybridization

HGUC – High-grade urothelial carcinoma

HRP – Horseradish peroxidase

ICC – Immunocytochemistry

IHC/ISH – Immunohistochemistry/in situ hybridization

LBC – Liquid based cytology

LGUC – Low-grade urothelial carcinoma

PUNLUMP – Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential

UC – Urothelial carcinoma.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (the authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- 2013. Institute of Population Based Cancer Research. Available from: https://www.kreftregisteret.no/Registrene/Kreftstatistikk/

- The Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytology (1st ed. 2016). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

- The positive predictive value of “suspicious for high-grade urothelial carcinoma” in urinary tract cytology specimens: A single-institution study of 665 cases. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124:811-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytomorphological characteristics of low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma for differential diagnosis from benign papillary urothelial lesions: Logistic regression analysis in surePath(™) liquid-based voided urine cytology. Cytopathology. 2016;27:83-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is a consistent cytologic diagnosis of low-grade urothelial carcinoma in instrumented urinary tract cytologic specimens possible. A comparison between cytomorphologic features of low-grade urothelial carcinoma and non-neoplastic changes shows extensive overlap, making a reliable diagnosis impossible? J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2015;4:90-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urine cytopathology: Challenges, pitfalls, and mimics. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:1019-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hadjinak T, ed. UroVysion FISH for detecting urothelial cancers: Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy and comparison with urinary cytology testing. Vol 26. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations; 2008. p. :646-51.

- A prospective comparison of uroVysion FISH and urine cytology in bladder cancer detection. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:247.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of urovysion and cytology for bladder cancer detection: A study of 1835 paired urine samples with clinical and histologic correlation. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:591-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Value of p16(INK4a) in the diagnosis of low-grade urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder in urinary cytology. Cancer Cytopathol. 2012;120:276-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- ProEx C as an adjunct marker to improve cytological detection of urothelial carcinoma in urinary specimens. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:320-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- P16(INK4a) expression analysis as an ancillary tool for cytologic diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:776-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- P16(INK4a)/Ki-67 dual labelling as a marker for the presence of high-grade cancer cells or disease progression in urinary cytopathology. Cytopathology. 2013;24:327-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunocytochemical staining for p53 and ki-67 helps to characterise urothelial cells in urine cytology. Cytopathology. 2016;27:456-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- The ki-67 protein: From the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol. 2000;182:311-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stem-cell ageing modified by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a. Nature. 2006;443:421-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- P16(Ink4a) overexpression in cancer: A tumor suppressor gene associated with senescence and high-grade tumors. Oncogene. 2011;30:2087-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gmbh RD, ed. CINtec?PLUS Cytology Kit. Mannheim, Germany: Roche; 2016.

- The effect of the small amount of formaldehyde in the surePath liquid when establishing protocols for immunocytochemistry. Cytojournal. 2016;13:27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protocol # 191: SurePath CINtec Plus. Procedure: XT CINtec PLUS Cytology. Benchmark XT IHC/ISH Staining Module 2015 October 02

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs Vol 8. (4th ed). Lyon, France: IARC; 2016.

- The expression patterns of p53 and p16 and an analysis of a possible role of HPV in primary adenocarcinoma of the urinary bladder. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95724.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic terminology for urinary cytology reports including the new subcategories 'atypical urothelial cells of undetermined significance' (AUC-US) and 'cannot exclude high grade' (AUC-H) Cytopathology. 2014;25:27-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- P16/Ki-67 dual labeling and urinary cytology results according to the new Paris system for reporting urinary cytology: Impact of extended follow-up. Cancer Cytopathol. 2017;125:552-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bladder cancer detection using FISH (UroVysion assay) Adv Anat Pathol. 2008;15:279-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in cytologic specimens using various fixatives. Diagn Cytopathol. 1996;15:78-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunostaining of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, MIB1 antigen, and c-erbB-2 oncoprotein in cytologic specimens: A simplified method with formalin fixation. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;17:127-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- An evaluation of potentially suitable fixatives for immunoperoxidase staining of estrogen receptors in imprints and frozen sections of breast carcinoma. Pathology. 1988;20:320-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of HER-2 status on FNAC material from breast carcinomas using in situ hybridization with dual chromogen visualization with silver enhancement (dual SISH) Cytojournal. 2010;7:21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Liquid based material from fine needle aspirates from breast carcinomas offers the possibility of long-time storage without significant loss of immunoreactivity of estrogen and progesterone receptors. Cytojournal. 2010;7:24.

- [Google Scholar]