Translate this page into:

Papanicolaou society of cytopathology system for reporting pancreaticobiliary cytology: Risk stratification and cytology scope - 2.5-year study

*Corresponding author: Dr. Abeer M Ilyas, MBBS, MD Pathology, Department of Pathology and Lab Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India. abeer.patho@aiimsbhopal.edu.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Ilyas MA, Bohra M, More NM, Naik LP. Papanicolaou society of cytopathology system for reporting pancreaticobiliary cytology: Risk stratification and cytology scope - 2.5-year study. CytoJournal 2022;19:33.

Abstract

Objectives:

Diagnosis of pancreatic lesions remains a clinical challenge. Early and accurate diagnosis is extremely important for improving the therapeutic usefulness of pancreatic cancers and Endoscopic ultrasonography - fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) cytology has come up with this advantage. For current study the authors evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNAC by applying PSC system for reporting pancreaticobiliary cytology and Calculated the malignancy risk associated with the diagnostic categories.

Material and Methods:

A retrospective study over the period of 2.5 years (April 2017 to Oct 2019) 60 patients in our cohort EUS-FNAC guided unstained fixed and unfixed slides received of pancreatic lesion and were stained with Papanicolau and Giemsa using standard technique and immunocytochemistry, where required Application of Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology system for reporting pancreaticobiliary cytology Histopathological and clinical follow-up were retrieved.

Results:

Our study has comparable results with sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 92.8%, 100%, 100%, and 92.59%, respectively. Fuurthermore, a diagnostic accuracy of 96.2%. Risk of malignancy is lower for benign and indeterminate category whereas it is higher for suspicious and malignant categories.

Conclusion:

The application of the new proposed terminology for pancreaticobiliary cytology brings standardization. Final diagnosis can be reached by the multidisciplinary approach of EUS-FNA cytology, cell block preparation, immunocytochemistry, and immunohistochemistry; if required, can be adopted as an alternative approach to biopsy. The present study showed high sensitivity and specificity for EUS-FNA in the diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma, which may influence the treatment plans of both surgeons and oncologists.

Keywords

Pancreatic lesions

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration

Papanicolaou Society

Cellblock

Immunocytochemistry

INTRODUCTION

Diagnosis of pancreatic lesions remains a clinical challenge. Early and accurate diagnosis is extremely important for improving the therapeutic usefulness of pancreatic cancers. Pancreatic cancers are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality and have become the fourth leading cause of death among cancers.[1] This poor survival rate reflects late presentation, nonspecific signs and symptoms, and limited diagnostic and therapeutic modalities.[2]

Imaging modalities have an important role in the diagnosis of pancreatic lesions, especially in pancreatic cancer which is not possible to be reliably diagnosed based on symptoms and signs alone because of the lack of specificity.[3] Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is one of the most sensitive and accurate modalities for detecting and evaluating pancreatic mass and staging of pancreatic cancer.[4] It gives us high-resolution images of the entire pancreas and has been shown to be superior to computed tomography (CT), US, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, or angiography in detecting tumors smaller than 3 cm in size.[5]

EUS -guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) is a relatively safe and accurate technique to acquire pancreatic cytology specimens for rapid pathologic diagnosis.[6] EUS- FNA cytology integrated with immunochemistry may allow definitive diagnosis of pancreatic lesions. However, until recently there was no widely accepted categorization system for pancreatic cytology obtained by EUS-FNA.

The newest installment on standard practice in Cytopathology from the Papanicolaou society of cytopathology (PSC) focuses on the pancreaticobiliary system.[7] The PSC guidelines for pancreaticobiliary cytology address indications, techniques, terminology and nomenclature, ancillary studies, and post-procedure management.[7-9] Management of pancreatic lesions depends on the risk of malignancy (ROM), which is primarily determined from the cytologic and radiologic evaluation findings. In the current study, we applied the new proposed terminology for pancreaticobiliary cytology to a retrospective set of EUSFNA pancreatic cytologic specimens and verified its sensitivity and specificity, correlating the results with the final surgical diagnoses.

Aims of our study

Evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNAC by PSC system for reporting pancreaticobiliary cytology

Cyto-Histological co-relation with imaging findings and clinical follow-up

Calculate malignancy risk associated with the diagnostic categories.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This is a retrospective study over the period of 2.5 years (April 2017 to Oct 2019) at a tertiary care center in the Department of Pathology. The study comprises 60 cases and all the cases were reported using the PSC system for reporting pancreaticobiliary cytology[10] which follows, (ROM)

Nondiagnostic

Negative (for malignancy)

Atypical (ROM: 44–62%)

Neoplastic: (a) Benign (b) Other

Suspicious (for malignancy) (ROM: 82–86%)

Positive/malignant (ROM: 85–90%).

EUS-FNAC guided fixed and unfixed slides received of the pancreatic lesion and were stained with Papanicolaou and Giemsa, respectively, using standard technique and immunochemistry, wherever required. Histo- pathological and clinical follow-up were retrieved from our archives. Patient characteristics such as age, gender, clinical history, and family history of pancreatic cancer were recorded. Imaging reports including EUS, US, CT, and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography were reviewed to assess the location, size, and characteristics of the pancreatic lesions. The final diagnosis was based on cellblock, Immunocytochemistry (ICC), Immunohistochemistry,and/or Histopathology findings.

FNA specimens of other abdominal lesions including peripancreatic lesions, lymph nodes, or bile duct mass lesions were excluded from the study. Onsite evaluation by cytologist was not available in these cases. The results of EUS-guided FNA were compared with the final diagnoses to calculate the accurate sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value.

Statistical analysis

The Pearson chi-square test was used to determine cytohistologic agreement and to assess the sensitivity and specificity of EUS-FNA specimens.

Estimation of ROM

The upper limit estimate of malignancy was calculated as malignant cases divide by patients who underwent surgical resection. The lower limit estimate of malignancy was calculated assuming that all patients without surgical follow-up likely had benign thyroid lesions.

RESULTS

A total of sixty EUS-FNA records and slides were retrieved from the archives. The average range of patient’s ages 45–55 Years with an average age of patients being 51 Years. There was a male preponderance with the ratio of 2:1. Abdominal pain, jaundice, and pruritus were the most common symptoms.

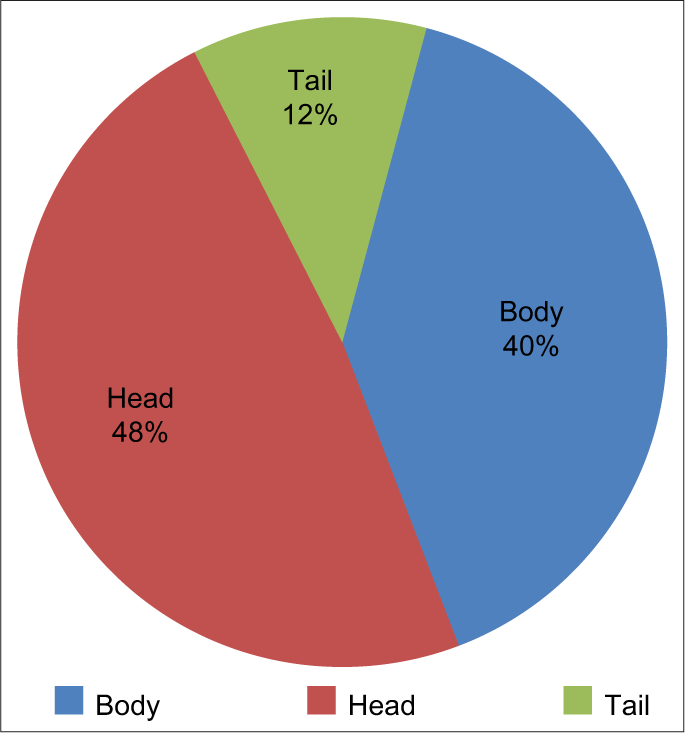

Location of the lesions, the head being most common comprising of 48% followed by body 40% and last tail 12% [Figure 1].

- Location of lesions of the pancreas.

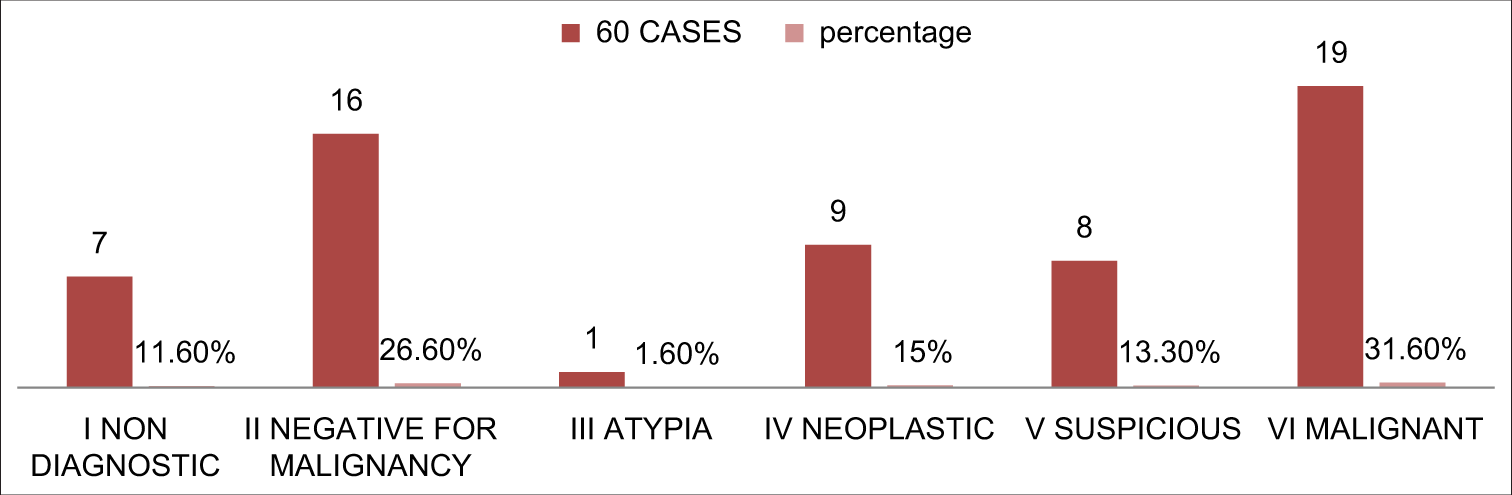

All the cases from our cohort were classified according to the new proposed terminology for the pancreaticobiliary cytology system [Figure 2]. Higher number of cases in category VI followed by category II and the least number of cases belonged to category III.

- Distribution of patients according to new proposed terminology for pancreaticobiliary cytology.

As illustrated in Table 1, there are seven cases (11.6%) belonging to category I, all the patients were lost to follow-up. Sixteen cases (26.6%) belonged to category II, amongst fourteen cases were of pseudocyst and one case of granulomatous. All these cases received medical treatment and are doing well. There was one case of para-deodenal pancreatitis which was confirmed on biopsy.

| Category | Cases (60) | Cytology | Histology | Concordant discordant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 7 (11.6) | Non diagnostic | Lost to follow-up | - |

| II | 16 (26.6) | Granulomatous (n=1) Pseudocyst (n=14) Para-duodenal pancreatitis (n=1) |

Received Medical treatment and on f/u Biopsy confirmed |

Concordant |

| III | 1 (1.6) | Cells showing Atypia (n=1) | Inflammatory | Concordant |

| IV | 9 (15) | Solid pseudo-papillary epithelial neoplasm (n=3) NET (n=6) |

Biopsy confirmed (2/6cases of NET were confirmed on ICC) |

Concordant |

| V | 4 (13.3) | Suspicious for Malignancy (n=4) | AdenoCa (n=3) Negative (n=1) |

1 Discordant |

| VI | 19 (31.6) | AdenoCa (n=8) Acinar Cell Ca (n=1) |

17 Biopsy confirmed,1 cell block Patient expired |

Concordant |

NET: Neuroendocrine tumor

We had one case (1.6%) of category III, there was a partial agreement of the case: the patient was diagnosed as cytologically as few atypical cells seen with benign epithelial cells present, but the biopsy revealed inflammatory lesion. There were nine cases (16%) of category IV: Others, amongst three cases of solid pseudo-papillary epithelial neoplasm which were confirmed on biopsy, and six cases of neuroendocrine tumor of which two cases were confirmed on ICC and 4 cases on biopsy. None of the cases belonged to category IV: Benign.

Four cases (13.3%) belonged to category IV, three cases were confirmed as Adenocarcinoma on biopsy and one case was negative for malignancy. Hence, we had one discordant in our study. Lastly, for category VI, there were total of nineteen cases (31.6%) 17 were Adenocarcinoma and confirmed on biopsy. There was one case where we received slides and cell block and we performed immunochemistry (IC) for confirmation of the diagnosis of Adenocarcinoma. One case of well-differentiated Acinar cell carcinoma, patient came with disseminated malignancy. Unfortunately, the patient passed away before his biopsy schedule.

As demonstrated in Table 2, an increasing risk for malignancy extending from benign to malignant. Our study shows higher ROM than anticipated by the PSC system.

| PSRPC | Cases | Final diagnosis | Our study (ROM) (%) | PSC (ROM) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (I) Non diagnostic | 7 | Non diagnostic | - | - |

| (II) Negative | 16 | Granulomatous (n=3) Pseudocyst (n=12) Para-duodenal pancreatitis (n=1) |

- | - |

| (III) Atypia | 1 | Cells showing Atypia (n=1) | Nil | 44–62 |

| (IV) Neoplastic a. Benign b. Others |

9 | Solid pseudo-papillary epithelial neoplasm (n=3) Neuroendocrine tumor (n=6) |

- | - |

| (V) Suspicious | 8 | Suspicious for Malignancy (n=4) | 87.5 | 82–86 |

| (VI) Malignant | 19 | AdenoCa (n=18) Acinic Cell Ca (n=1) |

100 | 85–90 |

| Total | 60 |

Overall; the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of EUS-FNA for diagnosing pancreatic lesions were 92.8%, 100%, 100%, and 92.59%, respectively, with the diagnostic accuracy of 96.22% [Table 3].

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Diagnostic accuracy (%) | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 92.8 | 100 | 100 | 92.59 | 96.22 | Our study |

| 93.15 | 93.7 | 99.15 | 97.5 | 96.2 | Nigam et al. |

| 95.4 | 100 | 100 | 92.3 | - | Wright et al. |

DISCUSSION

The present study showed that EUS-FNA is a useful diagnostic procedure in the evaluation of pancreatic lesions, especially adenocarcinoma. EUS-FNA was shown to have a high diagnostic accuracy of 96.22% and a high sensitivity and specificity for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. This is comparable to a study by Alizadeh et al.,[11] Nigam et al.[12] and Wright et al.[13]

The PSC has recently proposed a standardized terminology and nomenclature guidelines for pancreatic cytology. However, the ROM associated with each PSC category has been scarcely investigated. Layfield et al. reported the risks of malignancy were 13% for “negative,” 14% for “neoplastic,” 21% for “nondiagnostic,” 74% for “atypical,” 82% for “suspicious,” and 97% for “positive” respectively.[14] Sung et al. reported 4.5% for Category I, 2.5% for Category II, 25.3% for Category III, 0% for Category IV: Benign, 27.1% for Category IV: Others, 75% for Category V, and 87.9% for Category VI.[15] Hoda et al. reported the absolute ROM as 7.7% for the nondiagnostic category; 1.0% for negative; 28.0% for atypical; 0.0% for neoplastic: benign; 30.3% for neoplastic: other;

About 90.0% for neoplastic: other with HGA; 100% for suspicious; and 100% for positive.[16] Our findings were comparable with the above-mentioned literatures.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the findings in our study showed high sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of EUS-FNA in the diagnosis of pancreatic malignancy. Furthermore, it has high diagnostic accuracy. Final diagnosis can be reached by a combination of the EUS-FNA cytology, cell block preparation, and immunochemistry; if required, can be adopted as an alternative approach to biopsy. Implementation of these techniques complement each other and help reach early to a diagnosis which directly influences treatment plan.

A good communication is a bridge between confusion and clarity; a clear, upfront advantage of the new proposed terminology for pancreaticobiliary cytology is the standardization of terms among pathologist and the treating surgeon.

The new proposed terminology has easy application and may result in optimal treatment in most cases. Management of pancreatic lesions depends on the ROM and categories of the PSC system each carry an implied absolute ROM, increasing from the negative to positive categories.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Contribution from each author has been sufficient. The manuscript has been read and approved by all authors.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The study was approved by Institutional Ethics Committee Human Research Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College and General Hospital Ref : IHE/11/20.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

ACC – Acinar cell carcinoma

CT – Computed tomography

EUS – Endoscopic ultrasound

ERCP – Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

EUS-FNA – Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration

ICC – Immunocytochemistry

IC – immunochemistry

IHC – Immunohistochemistry

MRCP – magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

NET – Neuroendocrine tumor

PSC – Papanicolaou society of cytopathology

ROM – Risk of malignancy

SPEN – Solid pseudo-papillary epithelial neoplasm

US – Ultrasound.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

References

- Pancreatic cancer death rates by race among US men and women 1970-2009. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1694-700.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exocrine pancreatic cancer: Symptoms at presentation and their relation to tumour site and stage. Clin Transl Oncol. 2005;7:189-97.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endosonography-guided biopsy of mediastinaland pancreatic tumors. Endoscopy. 1998;30:32-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- optimizing diagnostic yield for EUS-guided sampling of solid pancreatic lesions: A technical review. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;9:352-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- CT-guided needle biopsy of the pancreas: A retrospective analysis of diagnostic accuracy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1610-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- How good is endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in diagnosing the correct etiology for a solid pancreatic mass?: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Pancreas. 2013;42:20-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standardized terminology and nomenclature for pancreatobiliary cytology: The papanicolaou society of cytopathology guidelines. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:338-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postbrushing and fine-needle aspiration biopsy follow-up and treatment options for patients with pancreatobiliary lesions: The papanicolaou society of cytopathology guidelines. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:363-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical evaluation, imaging studies, indications for cytologic study, and preprocedural requirements for duct brushing studies and pancreatic FNA: The papanicolaou society of cytopathology recommendations for pancreatic and biliary cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:325-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancreaticobiliary tract cytology: Journey toward “Bethesda” style guidelines from the papanicolaou society of cytopathology. Cytojournal. 2014;11:18.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic potency of EUS-guided FNA for the evaluation of pancreatic mass lesions. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:30-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUS-guided FNA in diagnosing pancreatic lesions: Strength and cytological spectrum. J Cytol. 2019;36:189-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outcomes of endoscopic ultrasound-guided pancreatic FNAC diagnosis for solid and cystic lesions at Manchester royal infirmary based upon the papanicolaou society of cytopathology pancreaticobiliary terminology classification scheme. Cytopathology. 2018;29:71-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malignancy risk associated with diagnostic categories defined by the papanicolaou society of cytopathology pancreaticobiliary guidelines. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122:420-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Update on risk stratification in the papanicolaou society of cytopathology system for reporting pancreaticobiliary cytology categories: 3-year, prospective, single-institution experience. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020;125:29-35.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk of malignancy in the categories of the papanicolaou society of cytopathology system for reporting pancreaticobiliary cytology. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2019;8:120-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]