Translate this page into:

Subcutaneous nodule in the chest – Uncommon presentation of a common disease

*Corresponding author: Preeti Singh, MD, DNB, Department of Pathology, Atal Bihari Vajpayee Institute of Medical Sciences and Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital, New Delhi, India. preetisingh.vmmc@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Singh P, Kaushal M, Marwah S. Subcutaneous nodule in the chest – Uncommon presentation of a common disease. CytoJournal 2021;18:22.

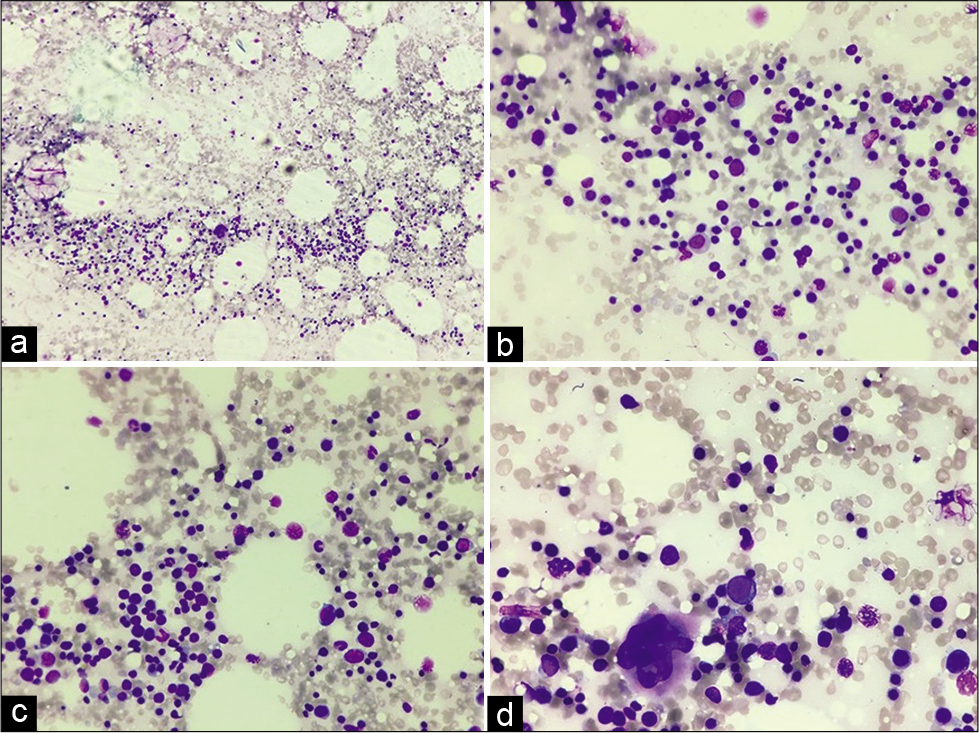

A 19-year-old female presented to us with a midline swelling in the upper chest for 6 months. Physical examination revealed a reddish-brown nodular midline swelling in the upper chest measuring 0.8 × 0.8 cm. Ultrasound findings suggested a well-defined subcutaneous swelling measuring 10 × 0.8 mm in size. Underlying bony cortex was intact with no erosion. X-ray chest revealed no abnormality. Fine-needle aspiration from the subcutaneous swelling showed moderately cellular smears, with the presence of myeloid cells, erythroid cells, histiocytes, and megakaryocytes. Erythroid and myeloid series cells were seen in different stages of maturation [Figure 1a-d]. Few adipocytic fragments and red blood cells were noted in the background.

- (a) Fine-needle aspiration smear showing moderate cellularity (40×, Giemsa stain), (b and c) Smears showing myeloid cells, erythroid cells in different stages of maturation (200×, Giemsa stain), (d) Smear showing hematopoietic cells with a megakaryocyte (400×, Giemsa stain).

Q1. What is your interpretation?

Leukemia cutis

Chronic myeloproliferative neoplasm

Extramedullary hematopoiesis

Primary myelofibrosis.

Please see the next page for answer and additional discussion on the topic

Answer

Q1: c. Extramedullary hematopoiesis.

Extramedullary hematopoiesis is defined as the production of blood outside the normal limits of the bone marrow.[1] In EMH, the cytological pattern is identical as in other sites such as spleen and liver. On FNAC reveals mixture of myeloid cells, erythroid cells, and megakaryocytes in various stages of maturation.

Leukemia cutis is the infiltration of neoplastic leukocytes or their precursors into the epidermis, the dermis, or the subcutis, resulting in clinically identifiable cutaneous lesions. Leukemia cutis may follow, precede, or occur concomitantly with the diagnosis of systemic leukemia. No blast cells were noted in the present case.

Diagnosis of myeloproliferative neoplasms needs hematological correlation.

Q2. Which of the following is true about EMH in case of thalassemia?

Skin is the most common site

Treatment is surgical removal of the mass

Usually occurs in liver, spleen, and lymph node

Presence of megakaryocytes is must for the diagnosis.

Q3. Which of the following is false about EMH?

Cutaneous lesions manifest as macules, papules, or nodules

Divided as para osseous and extraosseous

Cutaneous EMH is not seen in congenital infections

May represent a compensatory response to longstanding hypoxia.

Q4. Which of the following is not a microscopic feature of cutaneous EMH?

May resemble a fibrohistiocytic tumor

Dermal infiltrate predominantly composed of erythroid and myeloid elements

Chloroacetate esterase stain highlights the myeloid elements

Megakaryocytes are positive for glycophorin A immunostain.

FOLLOW-UP OF CASE

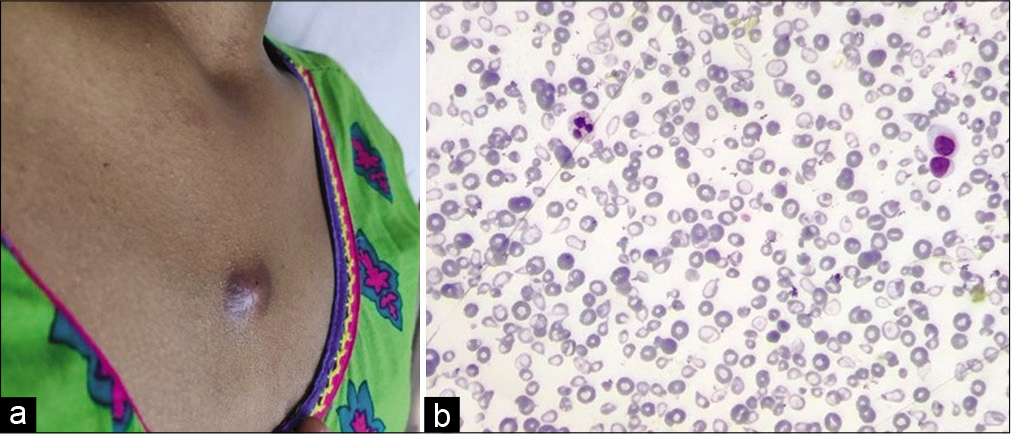

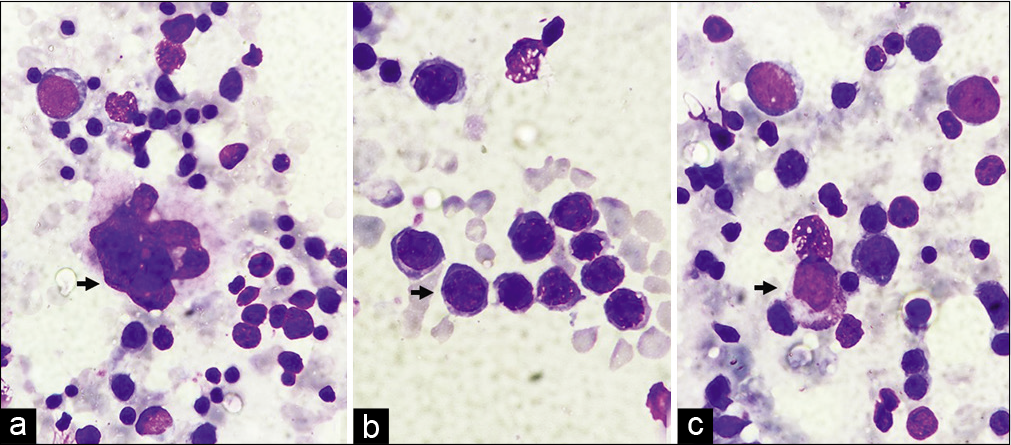

On further evaluation, patient was a diagnosed case of Beta-thalassemia major 8 years back. She has been treated with monthly blood transfusion and iron chelation therapy. She had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis, 9 years back for which she took category-1 anti-tubercular therapy. Per abdomen examination revealed palpable spleen crossing the umbilicus. Hematologic studies disclosed the following values: hemoglobin, 8.8 g/dl; WBC count, 11,200/mm3; with 64% polymorphs, 31% lymphocytes, 3% eosinophils and 2% monocytes; 6 nRBCs/100 WBCs; and platelet count, 150,000/mm3. Peripheral blood smears showed marked anisopoikilocytosis with microcytes, tear drop cells, target cells, and hypochromia [Figure 2a and b]. Repeat FNAC was done which showed similar morphology [Figure 3a-c].

- (a) A reddish-brown nodular midline subcutaneous swelling in the upper chest measuring 0.8 × 0.8 cm, (b) Peripheral smear showing marked anisopoikilocytosis with microcytes, tear drop cells, target cells, and hypochromia (200×, Leishman stain).

- (a) Megakaryocyte (arrow) (1000×, Giemsa stain), (b) Erythroid Island with normoblast (arrow) (1000×, Giemsa stain), (c) myeloid cell (arrow) (1000×, Giemsa stain).

Answers

Q2 – c. Usually occurs in liver, spleen, and lymph node

Q3 – c. Cutaneous EMH is not seen in congenital infections

Q4 – d. Megakaryocytes are positive for glycophorin A immunostain.

SUMMARY

During embryonic life, erythropoiesis normally takes place in this fashion, with blood production occurring in the liver, lymph nodes, and spleen. At birth, extramedullary hematopoiesis ceases and blood production shifts to the bone marrow. However extramedullary blood-producing connective tissue cells are still present in the child and adult, which, under certain circumstances, can once again become active. In this condition, foci of extramedullary hematopoiesis may arise within soft tissues.[1]

EMH in Thalassemia usually occurs at liver, spleen, kidney, lymph nodes, and paravertebral region.[2] Skin has not been described in literature so far. Skin as site for EMH has been described in myelofibrosis that too in an older patient with a mean age of 50 years.[3] Skin involvement by EMH is uncommon and has an estimated prevalence of 0.4% of cases in myelofibrosis.[4]

The cutaneous EMH lesions can manifest in a variety of ways: as macules, papules, nodules, and even ulcers. Several cases have been described of angioma-like cutaneous lesions and others with blisters and bleeding.[4]

Cytologically EMH composed of a combination of myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryocyte precursors. The erythroid precursors predominate in children, whereas megakaryocytes predominate in adults.[5]

EMH can be divided into two type: The first show para osseous foci resulting from herniation of medullary tissue from the adjacent bone as it is seen in hemolytic anemia where the marrow is hyperactive and a second type which shows extra osseous extramedullary hematopoiesis with foci in soft tissues. If the “mass” is in a para osseous location, CT or plain radiographs should be obtained to look for areas of adjacent bone destruction and for evidence of marrow expansion.[1] In our case, ultrasound findings showed a well-defined subcutaneous mass with no underlying bony erosion.

It has been described in many types of severe anemia, polycythemia, leukemia, lymphoma, hyperparathyroidism, rickets, chronic infections, and following radiation exposure, poisoning, or neoplastic replacement of the bone marrow.[1] To compensate for chronically low hemoglobin level in conditions such as b thalassemia major, myeloproliferative disorders, and other blood dyscrasias, hematopoiesis is upregulated and organs outside the bone marrow get involved in the production of red blood cells.[6] The incidence of EMH in patients with thalassemia intermedia may reach up to 20% compared to TM patients where the incidence is less than 1%.[7]

However, it has been reported nearly in every organ, but is frequently seen in hepatosplenic areas which can potentially produce fetal hemoglobin. Non-hepatosplenic EMH has been reported in numerous sites, such as lymph nodes, pleura, thyroid, maxillary antrum, the falx cerebri, pericardium, skin, synovium of joints, lungs, thymus, breast, and the dura of the brain and spinal cord.[1,8]

Specific treatment may not be required unless EMH is accompanied by symptoms. Treatment options for thalassemia patients with EMH depend on the location and mass effect symptom and include surgery, radiation, blood transfusion, and hydroxyurea or various combinations thereof.[8]

In the present case, the patient is a young female presenting with subcutaneous swelling without underlying bony connection. FNAC revealed extramedullary hematopoiesis containing hemopoietic elements of all the three lineages. So far in the literature, cutaneous EMH had not been described in thalassemia; our case is the first case with cutaneous EMH in thalassemia patient.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is case without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from institutional review board (IRB) (or its equivalent).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

CT – Computed tomography

EMH – Extramedullary hematopoiesis

FNAC – Fine needle aspiration cytology

nRBC – Nucleated red blood cells

TM – Thalassemia Major

WBC – White blood cells.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double--blind model (the authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

References

- Ultrasound appearance of extramedullary hematopoiesis. J Ultrasound Med. 1987;6:283-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinal cord compression in beta-thalassemia: Case report and review of the literature. Spinal Cord. 2004;42:117-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Extramedullary hemopoiesis of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:58-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A case of cutaneous extramedullary hematopoiesis associated with idiopathic myelofibrosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:297-300.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous extramedullary hematopoiesis in myelofibrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:351-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Extramedullary hematopoiesis in beta thalassemia major: Multisystem involvement. OMICS J Radiol. 2016;5:234.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adrenal extramedullary hematopoiesis associated with b-thalassemia major. Hematol Rep. 2012;4:e7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retrocrural masses of extramedullary hemopoiesis in beta-thalassemia. Magn Reson Imaging. 1993;11:1227-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]