Translate this page into:

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) of subcutaneous lesion: A diagnostic dilemma on cytology

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

A 20-year-old female presented with a swelling in the suprapubic region for the past 1 year. There was a history of excision with delayed wound healing at the same site 1 year back. Ultrasound showed a subcutaneous soft-tissue mass measuring 2.56 cm × 1.72 cm suggestive of a desmoid or fibroblastic lesion. No mass was found in any of the abdominal and pelvic organs. There was no intrapelvic extension, and the underlying muscles and bones appeared normal.

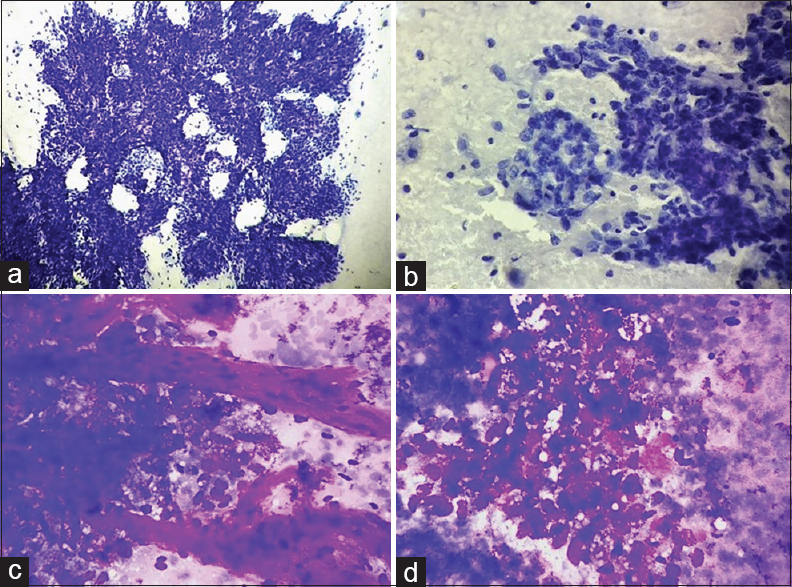

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) was performed [Figure 1]. The aspirate showed high cellularity with atypical epithelial cells arranged in papillae, clusters, groups as well as singly scattered showing prominent vascularity. Few mitoses were noted with bizarre nuclei, giant cells, and necrosis in the background.

- (a-d) Smears showing high cellularity comprising atypical epithelial cells arranged in papillae (a; Pap, ×200), clusters, glandular pattern (b; Pap, ×400), groups as well as singly scattered showing prominent vascularity (c; Giemsa, ×400). Cells are round to oval with moderate pleomorphism, marked overlapping, and overcrowding with hyperchromatic to coarsely granular chromatin (c), inconspicuous to evident nucleoli and a moderate amount of finely vacuolated cytoplasm (d; Giemsa, ×400)

QUESTION

Q1: What is Your Interpretation?

-

Malignant lesion

-

Tuberculosis

-

Blood clots

-

Nonneoplastic lesion

Answer 1: Option a – Malignant lesion

Explanation

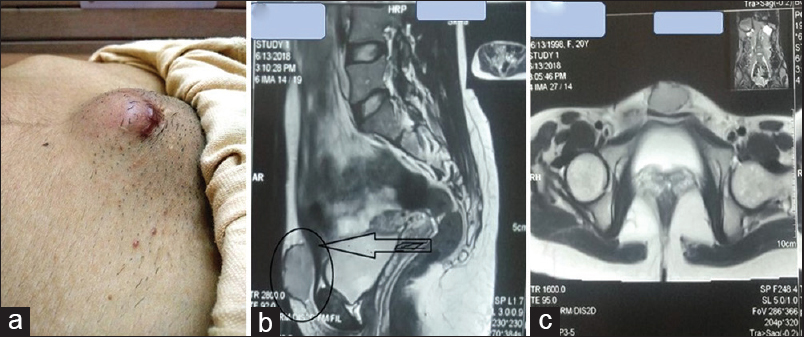

MRI of the pelvis and abdomen showed a well-defined subcutaneous suprapubic mass causing posterior displacement of the anterior abdominal wall. No mass was found in any of the abdominal and pelvic organs. There was no intrapelvic extension, and the underlying muscles and bones appeared normal [Figure 2]. Hence, a primary cutaneous malignancy was considered as one of the differentials.

- (a and c) A photograph showing an enlarged subcutaneous mass in the suprapubic region. (b and c) MRI of the pelvis and abdomen showing a well-defined subcutaneous midline heterogeneously enhancing suprapubic mass measuring 40 mm × 35 mm × 22 mm

Figure 1a–d: Cytological smears from the suprapubic swelling (a-d)

Q2: WHAT IS THE MOST LIKELY CYTOLOGICAL DIAGNOSIS?

Answer: The following differentials were considered:

-

Malignant cutaneous tumor

-

Malignant cutaneous epithelial tumor with sebaceous differentiation

-

Metastatic carcinoma with clear cells

-

Germ-cell tumor (GCT).

Explanation

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) was done from multiple sites. Smears prepared showed high cellularity comprising atypical epithelial cells arranged in papillae, clusters, groups as well as singly scattered showing prominent vascularity [Figure 1a–d]. Cells were round to oval and showed moderate pleomorphism, marked overlapping and overcrowding with hyperchromatic to coarsely granular chromatin, inconspicuous to evident nucleoli, and moderate amount of finely vacuolated cytoplasm [Figure 1c and d]. Few mitoses were also noted with the presence of bizarre nuclei, giant cells, and necrosis in the background.

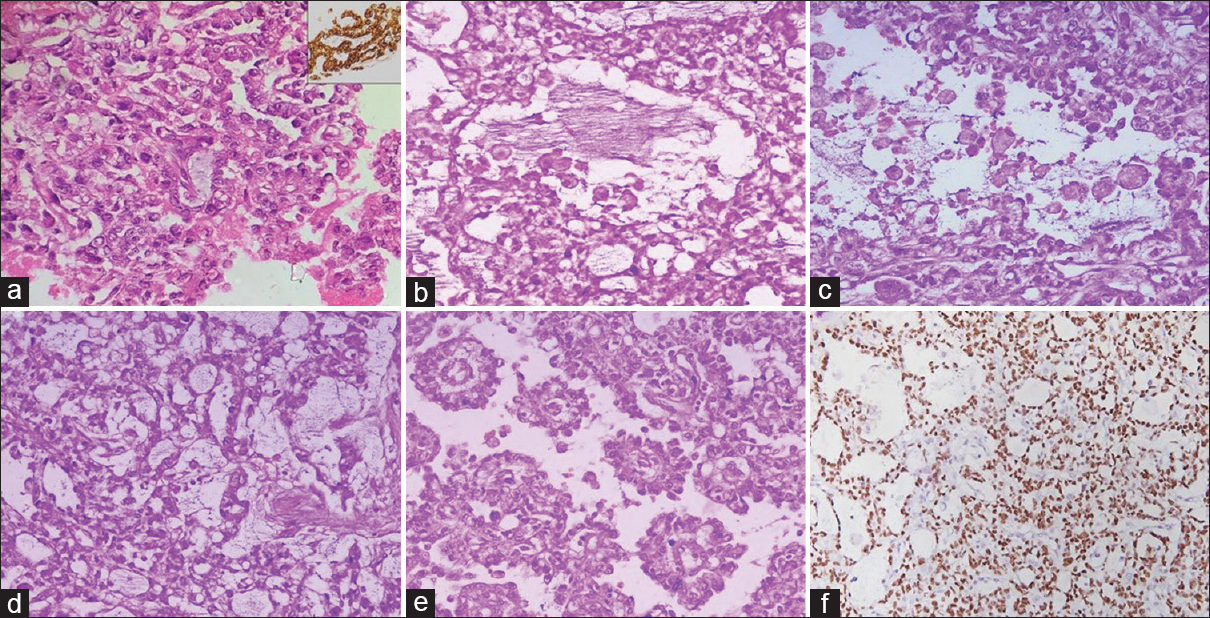

Cytopathological features along with radiological findings and immunohistochemistry on cell block [panCK positivity; Figure 3a and inset] were suggestive of the following differentials: (a) malignant cutaneous epithelial tumor with sebaceous differentiation, (b) metastatic carcinoma with clear cells, and (c) GCT. In the present case, based on cytology features, the first differential diagnosis considered was sebaceous carcinoma.

- (a-f) Cell block section showing atypical epithelial cells in the glandular pattern (a; H and E, ×400) and showing strong panCK positivity (a, inset). (b and c) Sections showing atypical epithelial cells in glandular pattern with many foamy cells (b and c; H and E, ×400). (d and e) Tumor cells in a reticular pattern (d; H and E, ×400) and many Schiller–Duval bodies (e; H and E, ×400). (f) Image showing tumor cells with strong SALL4 positivity (IHC, ×200)

The points in favor of it were subcutaneous location of lesion, firm painless swelling, radiological evidence showing no involvement of any abdominal organs, particularly ovaries, cells arranged in clusters and showing pleomorphic, centrally located nuclei containing coarse, irregular chromatin, and abundant vacuolated cytoplasm. However, the young age of the patient, with tumor cells arranged in papillary pattern, absence of prominent nucleoli or frequent mitosis, and necrosis were the points which did not favor sebaceous carcinoma.

Metastatic carcinoma with clear cells was another possibility considered on cytology due to the arrangement of cells in papillary pattern and characteristic clear cell cytomorphology favoring malignancy. However, in the absence of clinical symptoms and radiological evidence of any primary lesion, this diagnosis was not favored in a young female.

The third possibility of GCT was considered based on the cytological features. The points in favor were young age of the patient, midline location of mass, tumor cells arranged in papillae with cells showing pleomorphic ovoid to elongated enlarged nuclei, granular chromatin, and moderately abundant finely vacuolated basophilic cytoplasm. However, there was no evidence of gonadal involvement in radiological evaluation. Therefore, in view of a malignant epithelial tumor, surgical excision and histopathological correlation were advised. A surgical excision of the tumor was advised and sent for histopathological examination.

Figure 3a–f: Histological images and IHC images from the excised supra-pubic mass (a-f).

Q3: WHAT IS THE DEFINITIVE DIAGNOSIS?

-

Malignant cutaneous tumor

-

Malignant cutaneous epithelial tumor with sebaceous differentiation

-

Metastatic carcinoma with clear cells

-

GCT.

Answer 3: Option d – GCT-extra-ovarian yolk sac tumor

Explanation

Grossly, a specimen of single skin-covered soft-tissue mass was received measuring 8.5 cm × 6 cm × 3.5 cm. On serial sectioning, a nodular circumscribed growth was identified measuring 3.2 cm × 3.5 cm × 5 cm, with gray-white and focal hemorrhagic areas. Multiple sections showed an ill-circumscribed tumor composed of pleomorphic cells arranged in solid, reticular, microcystic, and pseudopapillary pattern against a loose myxoid background [Figure 3b–e]. Many Schiller–Duval bodies were also noted [Figure 3e]. These tumor cells had moderate amounts of vacuolated cytoplasm and pleomorphic vesicular nuclei with inconspicuous to small nucleoli. Many tumor cell nests showed a dyscohesive population of large cells with abundant foamy cytoplasm [Figure 3b and c]. Intracytoplasmic hyaline globules were also noted.

In view of histological features, a diagnosis of extra-ovarian germ-cell tumor with possibility of yolk sac tumor was considered, and serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) estimation and immunohistochemistry were advised. The serum AFP was considerably raised with the value of 99.3 ng/ml (normal range: 0–15 ng/ml). Immunohistochemical markers such as HCG, CA19.9, CA 125, and Carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA) were within normal range. PanCK and SALL4 [Figure 3f] showed strong positivity. A definitive diagnosis of yolk sac tumor was made based on the histological, biochemical, and immunohistochemical findings.

DISCUSSION

Yolk sac tumor, also called as endodermal sinus tumor, is a rare and highly malignant GCT.[1] Yolk sac tumor is the predominant variant of germ-cell tumors in newborns and younger children, while later in life, a wide range of other histologic subtypes are seen.[12345] It is a highly malignant tumor accounting for about 10% of malignant GCTs.[12] Most yolk sac tumors of the female genital tract occur in the ovaries. However, rare cases have been reported in the vulva, cervix, and endometrium.[123456] Very rarely, sites such as omentum, mediastinum, retroperitoneum, and sacrococcygeal region have also shown evidence of primary extra-ovarian yolk sac tumor.[456789] The incidence of extragonadal tumors is higher in young females, while intracranial/intraspinal tumors are more common in boys at an older age. FNA forms the first line of investigation of superficial primary or metastatic germ-cell tumors. However, they invite a wider range of differential diagnosis due to the unusual location. A thorough clinical, radiological, and biochemical workup is necessary for reaching a conclusive diagnosis.

Yolk sac tumor is a malignant GCT showing differentiation into primitive endodermal structures. This tumor was also previously known as endodermal sinus tumor because of the histological similarity to the extra-embryonal structures of the early embryo. It is the third most common malignant GCT of the ovary and constitutes about 1% of all ovarian malignancies.[34] It originates typically from reproductive organs. However, in 10%–15% of the cases, it occurs in the extragonadal sites including mediastinum, sacrococcygeal region, cervix, vulva, pelvis and retroperitoneum, and even more rarely in the abdomen and retroperitoneum.[456789]

GCTs consist of neoplastic cells arising from germline cells. They occur either in the testis or ovary or rarely outside the gonads. Several theories have been postulated regarding the histogenesis of extragonadal yolk sac tumor. These are as follows: (1) arrested migration of or misplaced germ cells during embryogenesis, (2) reverse migration of germ cells, (3) abnormal differentiation of somatic cells, (4) derivation from pluripotential stem cells within a somatic tumor, (5) origin from residual fetal tissue following incomplete abortion, and (6) metastasis from an occult gonadal primary.[3456]

The most common cause of the extragonadal location of yolk sac tumor is either malignant transformation of aberrantly migrated primordial germ cell misplaced during the embryogenesis or by a metastatic lesion of an undetected primary gonadal GCT not yet macroscopically visible or already spontaneously regressed.[345] Extragonadal yolk sac tumors are rare and typically occur in midline locations. Ungerleider et al.[4] cited 17 cases of this tumor at the extragonadal site from literature, of which ten cases were in the vagina, two cases in the pelvis, and one each in the broad ligament, retroperitoneum, maxillary sinus, cervix, and brain. He reported the first case in the region of the vulva. Cutaneous extragonadal yolk sac tumor is very rare. Till now, to the best of our knowledge, only one case has been reported by van den Akker et al.[5] in 2017 on the anterior abdominal wall in an 18-month-old female child. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second report of the subcutaneous presentation of a primary yolk sac tumor in the abdominal wall of a young female.

Yolk sac tumors are large, with an average diameter of 16 cm. Their cut surface is tan, white, or gray with small or large cysts and areas of hemorrhage and necrosis. Numerous patterns of growth have been described, mixtures of which are present in most tumors.[345] The most common and distinctive patterns are the reticular or microcystic pattern and the endodermal sinus pattern. The reticular pattern consists of a loose meshwork of microcystic spaces lined by a single layer of flattened or cuboidal cells having clear or amphophilic cytoplasm and atypical, hyperchromatic nuclei. The endodermal sinus pattern is also known as the festoon or pseudopapillary pattern. It consists of anastomosing glands and papillae, the linings of which are draped or “festooned” by columnar cells with clear or amphophilic cytoplasm and fusiform, hyperchromatic nuclei.

Schiller–Duval bodies are most often associated with this pattern and are diagnostic of yolk sac tumor, seen in about two-thirds of cases. These are glomeruloid structures in which fibrovascular papillae lined by columnar tumor cells project into glands or cystic spaces lined by cuboidal cells. The endodermal sinus pattern often merges into the closely related alveolar-glandular pattern, in which anastomosing tubules or glands are surrounded by a myxoid or spindle cell stroma. The glands are lined by cuboidal or columnar cells that are often stratified into multiple layers or form small papillae. Other variants noted are endometrioid-like variant, intestinal pattern, solid pattern, polyvesicular vitelline pattern, and rarely hepatoid pattern. Hyaline globules and hyaline material in stroma are also seen in yolk sac tumor.

Billmire et al.[6] studied 25 children with malignant GCTs of the abdomen and retroperitoneum as the primary site. Most tumors were of advanced stage at diagnosis, and in 15 patients, histology showed pure yolk sac tumor. Of the 25 patients, four patients had their primary site located at the abdominal wall; however, none were classified as yolk sac tumor. Maubec et al.[7] reported an overview of primary skin GCTs, 16 of the 19 patients were children, and mature teratoma was the most frequent diagnosis. Tekgündüz et al.[8] described a 3-year-old girl with a subcutaneous paraspinal yolk sac tumor with metastatic disease located in the scar tissue at the surgical site and lumbar vertebrae.

Alpha-feto protein (άFP) is regarded as a characteristic tumor marker of malignant GCTs and epithelial liver tumors.[8910] It is not tumor specific. Elevated άFP in the serum of a child is also associated with benign conditions, such as hepatic disorders, hereditary disorders, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other malignant tumors (e.g., hepatoblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and pancreatoblastoma).

Positive staining for AFP is the most characteristic immunohistochemical finding in yolk sac tumor, although staining is often weak and focal.[910] Other stains that are typically positive in yolk sac tumor are SALL4 and HNF-1 (both are nuclear stains) and glypican-3 (cytoplasmic stain). However, negative expression for OCT4, NANOG, SOX2, CD117, D2-40, and CD30 seen in yolk sac tumor helps in differentiating this tumor from other malignant GCT. Few studies have shown that AE1/AE3 stain is also helpful in evaluating germ-cell tumors, showing strong cytoplasmic staining.

Yolk sac tumors most often present in the 1st year of life and rarely with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis. Elevation of άFP is prognostically important. Complete surgical excision of the cutaneous lesion along with chemotherapy can be used for treating the patients. Without appropriate treatment, the tumor is highly aggressive, but with the combined treatment of surgery and adjuvant multi-agent platinum-based chemotherapy, a survival rate >90% can be achieved. However, despite the availability of highly effective chemotherapy, initially, the patient is put under observation. If the tumor recurs, then effective chemotherapy is given. The currently used regimens have comparable efficacy: cisplatin, etoposide, and ifosfamide (PEI); carboplatin and PEI; bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin; and carboplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin.[8910]

SUMMARY

We describe a rare case of recurrent primary extra-ovarian, subcutaneous yolk sac tumor in the suprapubic region. Following cytological and radiological evaluation, the patient was subjected to a wide local resection. The present case highlights the importance of radiology and histopathology in conjunction with serum markers and IHC in making a final diagnosis of yolk sac tumor. This case report also makes the clinicians aware that yolk sac tumor can present in an unusual extragonadal location. Hence, a multidisciplinary approach is essential in a definitive diagnosis of this variant of germ-cell tumor.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL THE AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENTS BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE. Each author has participated sufficiently in work and takes public responsibility for the appropriateness of content of this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is a case report without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

-

AFP: Alpha-feto protein

-

CEA: Carcino-embryonic antigen

-

FNAC: Fine needle aspiration cytology

-

GCT: Germ cell tumor

-

IHC: Immunohistochemistry

-

MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Germ cell trophoblastic and other gonadal neoplasms ICCC X 1975–2004. In: Ries L, Melbert D, Krapcho M, eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 2007. p. :125-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Germ cell tumors in atypical locations: Experience of the TGM 95 SFCE trial. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:646-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endodermal sinus tumor: The stanford experience and the first reported case arising in the vulva. Cancer. 1978;41:1627-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Yolk sac tumor in the abdominal wall of an 18-month-old girl: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11:47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant retroperitoneal and abdominal germ cell tumors: An intergroup study. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:315-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mixed nonseminomatous germ cell tumor presenting as a subcutaneous tissue mass. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:523-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Asubcutaneous paraspinal yolk sac tumor in a child. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:e115-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alpha-fetoprotein levels correlate with the pathologic grade and surgical outcomes of pediatric retroperitoneal teratomas. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25:331-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Randomized comparison of combination chemotherapy with etoposide, bleomycin, and either high-dose or standard-dose cisplatin in children and adolescents with high-risk malignant germ cell tumors: A pediatric intergroup study – Pediatric Oncology Group 9049 and children's cancer group 8882. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2691-700.

- [Google Scholar]