Translate this page into:

An unusual presentation of carcinoma in gallbladder

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

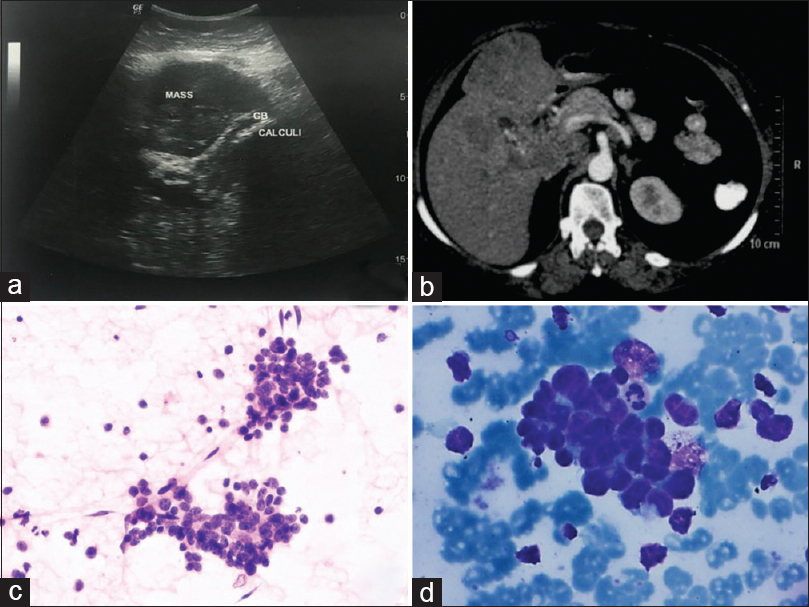

A 54-year-old female presented with dyspnea, yellowish discoloration, and pain in upper abdomen for 2 months subsequently associated with weight loss. She presented with bilateral pleural effusion while her investigations were going on. The ultrasound of the abdomen showed cholelithiasis and a gallbladder (GB) mass measuring 10 cm × 6 cm × 5 cm, invading the liver parenchyma [Figure 1a]. The computed tomography (CT) showed similar features with periportal lymphadenopathy [Figure 1b]. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) smears from the mass are shown in Figure 1c and d.

- Ultrasonography showing gallstone and mass arising within the gallbladder and invading the liver parenchyma (a). Computed tomography image showing gallbladder wall thickening with contiguous infiltration of adjacent segment 5 and 4b of the liver with gallbladder calculi and periportal lymph nodes (b). Fine-needle aspiration cytology smears showing clusters of tumor cells (H and E, ×100) (c), with characteristic nuclear molding (MGG, ×400) (d)

QUESTION

Q1: What is your interpretation?

-

Benign lesion

-

Lymphoma

-

Small-cell carcinoma (SmCC)

-

Adenocarcinoma

ANSWER 1

The correct cytopathological interpretation is,

c. Small cell carcinoma

Extrapulmonary SmCC is uncommon and seen in <5% of total SmCC.[1] SmCC arising within the GB is very rare. In largest series of GB carcinoma on FNA published recently, the reported incidence of SmCC was 1.3%.[2] The morphology of extrapulmonary SmCC is similar to seen in pulmonary SmCC; however, the same should be confirmed by immunohistochemistry (IHC).[3]

FEATURES FAVORING SMALL-CELL CARCINOMA

-

Fine dark chromatin

-

Absent or inconspicuous nucleoli

-

Scant cytoplasm.

The cytological features of SmCC and pertinent differential diagnoses are discussed as follows: The cells are usually distributed as loosely cohesive clusters and singly dispersed cells with variable nuclear molding. The cell size is 2–2.5 times that of lymphocytes, with scant cytoplasm, hyperchromatic nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, finely granular chromatin, and markedly increased mitoses and apoptosis. Neuroendocrine differentiation is supported by positive immunostaining for CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin.[4] Cytokeratin marker (CAM 5.2) often shows perinuclear dot-like positivity.

Overlapping features with lymphoma include singly dispersed cell population and similarities in cytomorphology inclusive of high nucleocytoplasmic ratio and inconspicuous nucleoli. However, the background often reveals lymphoglandular bodies in the smears obtained from the lymphoma. Significant crush artifact is seen in both the tumors. Immunohistochemical staining of cell block material for CD45 and neuroendocrine markers is helpful. Overlapping features with adenocarcinoma include gland-like differentiation. Poorly differentiated tumors reveal singly dispersed cells. The presence of rosettes and nucleocytoplasmic polarity in neuroendocrine tumors may mimic adenocarcinoma. In addition, it is common to have combined small cell and adenocarcinoma, which should be considered in the differential diagnosis.[4] The differential diagnosis of melanoma should also be kept in mind, given the singly dispersed population of cells with high nucleocytoplasmic ratio. The presence of melanin pigments and specific immunohistochemical markers such as Melan-A, SOX-10, and HMB-45 will differentiate these two lesions.

FOLLOW-UP OF THE CASE

The patient succumbed to illness after few days of diagnosis.

ADDITIONAL QUIZ QUESTIONS

-

Pleural fluid – What is the cytological interpretation of effusion?

-

No malignant cells seen

-

Benign mesothelial cell proliferation only

-

Metastatic adenocarcinoma

-

Metastatic SmCC

-

-

Which panel of immunohistochemical markers will confirm the diagnosis of SmCC on cell block?

-

Cytokeratin, CD56, Napsin A

-

Synaptophysin, chromogranin, CD56

-

Napsin A, Cytokeratin 5/6, Wilms’ tumor (WT1)

-

CEA, WT-1, CD45

-

-

How helpful will be thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) in differentiating SmCC of lung from primary GB SmCC??

-

It will be helpful as TTF-1 is positive only in SmCC of lung

-

It will not be helpful as TTF-1 is positive only in adenocarcinoma lung and not in SmCC

-

It will not be helpful as TTF-1 is not a specific marker for origin of SmCC from the lung

-

None of the statement is correct.

-

ANSWERS

(1) d, (2) b, (3) c

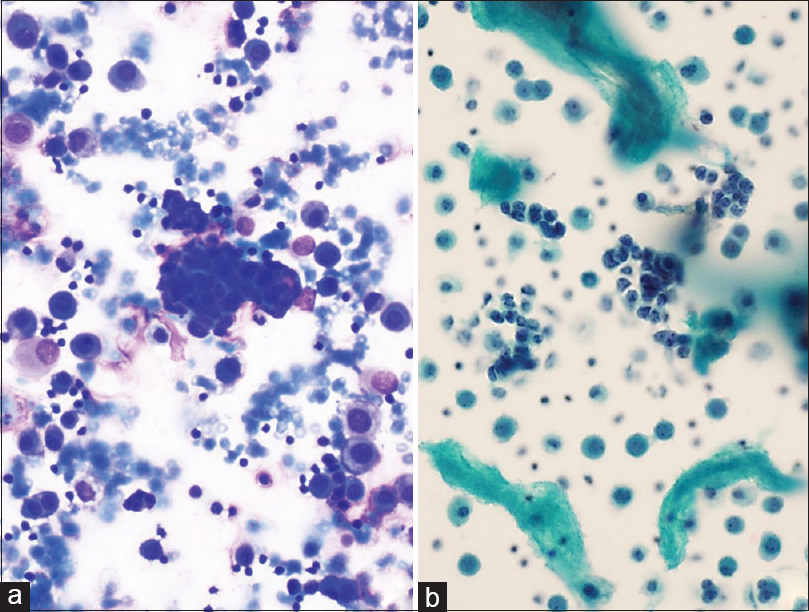

(1) d [Figure 2]: The smears of effusion cytology show similar malignant cells in clusters as described on smears. They show nuclear features of SmCC such as nuclear hyperchromasia, nuclear molding, and granular chromatin. The background shows mesothelial cells as a distinct cell population in the background.

- Similar tumor cells are noted within the pleural fluid effusion smears. Background showing mesothelial cells (a) MGG, ×200, (b) PAP, ×200

We have to remember that the key diagnostic features of SmCC do not include cell size and neuroendocrine differentiation. SmCC can show unexpectedly large cells or some tumors may have small cells. Neuroendocrine differentiation in non-SmCC is not uncommon and sometimes may not be demonstrable in SmCC.[5] Sampling variation, variable degree of differentiation, and heterogeneity of the tumor make it a diagnostic challenge.[5]

The chest CT scan did not show any mass lesion in lungs. A large mass arising from GB was identified and was considered a primary lesion. The SmCC of GB is uncommon and pleural effusion has never been described. A recent series of malignant effusion cytology[6] showed SmCC metastasis to pleural effusion, showing similar morphology as described in our case.

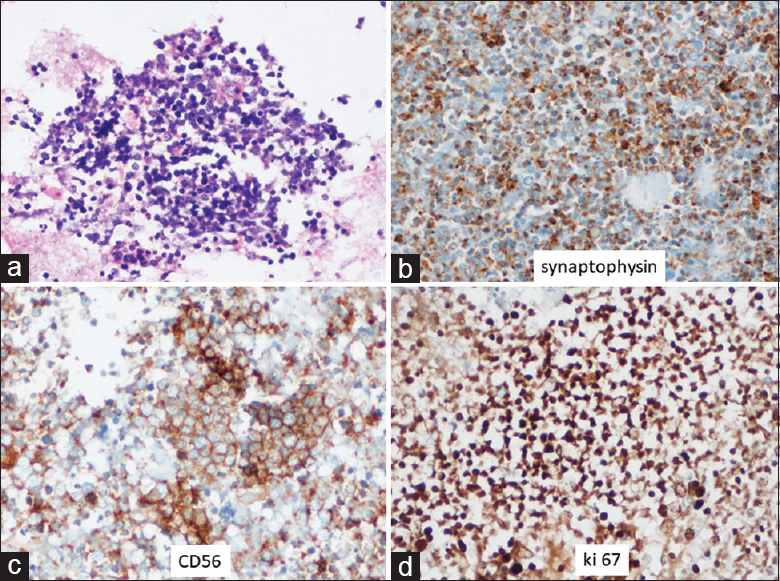

(2) b [Figure 3]: The SmCC tumor cells can show positivity for cytokeratin, but it cannot confirm a diagnosis as it is positive in majority of epithelial and mesothelial cells as well. Similarly, monoclonal CEA is also nonspecific. A panel of markers such as calretinin, D2-40, CK5/6, and WT-1 are positive in mesothelioma and can differentiate it from SmCC.[7] SmCC is a high-grade neuroendocrine tumor and shows positive immunostaining for neuroendocrine markers such as synaptophysin and CD56 as was in this case.[8] It also has high proliferative index (>20%) as was seen in this case [Figure 3d]. The typical cytomorphology on fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and IHC on cell block showing positivity for synaptophysin and CD56 assisted in clinching the correct diagnosis.

- The cell block showing sheets and clusters of tumor cells (H and E, ×200) (a). The tumor cells are positive for synaptophysin and CD56 DAB, ×400 (b-c). Ki 67 index is >80% DAB, ×400) (d)

(3) b: TTF-1 is positive in 80% of lung SmCC and are seen in 7%–80% of extrapulmonary SmCC.[910] Therefore, TTF-1 cannot be used to localize the primary origin of the tumor. A mass lesion at the GB fossa and no detectable lesion in the lung on CT scan ruled out its pulmonary origin.

BRIEF REVIEW OF THE TOPIC

SmCC of GB is associated with cholelithiasis as was seen in the present case. The cell of origin is considered to be multipotent stem cell or neuroendocrine cells in gastric metaplasia secondary to cholelithiasis.[11] Being an aggressive tumor, regional and distant metastasis is seen in 66% of patients at the time of diagnosis.[12] SmCC is seen in older patients and is more common in females.[13] The overall survival in one of the largest meta-analyses of these cases is reported to be 13 months.[13] The cytomorphology is diagnostic and IHC is required for confirmation.

We wish to highlight an uncommon variant of GB carcinoma with an uncommon clinical presentation. The clinical presentations and radiology of SmCC are similar to other GB malignancies. Furthermore, it is not a common site for trucut biopsy, so FNA remains the only reliable technique for diagnosis. The importance of cell block preparation during FNA is also emphasized by this case, which is essential for proper tumor characterization.

To the best of our knowledge, pleural fluid metastasis has never been described in a case of SmCC of GB. In the present case, the pleural fluid smears showed tumor cells with typical morphology of SmCC.

SUMMARY

Cytology plays an important role in the diagnosis of GB malignancies. Cytomorphology might be sufficient in majority of the tumors of that location, but a few rare ones require IHC for confirmation.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declared that they qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is a quiz case without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from the institutional review Board (or its equivalent).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

CT - Computed tomography

FNA - Fine-needle aspiration

GB - Gallbladder

IHC - Immunohistochemistry

SmCC - Small-cell carcinoma.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Extrapulmonary small-cell carcinoma: A single-institution experience. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:250-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spectrum of gallbladder malignancies on fine-needle aspiration cytology: 5 years retrospective single institutional study with emphasis on uncommon variants. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45:36-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytomorphology of neuroendocrine tumours of the gallbladder. Cytopathology. 2016;27:97-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- The use of immunohistochemistry improves the diagnosis of small cell lung cancer and its differential diagnosis. An international reproducibility study in a demanding set of cases. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:334-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Art & Science of Cytopathology. Diagnosis Cytopathology. (2nd ed). Chicago, USA: American Society of Clinical Pathologists Press; 1997. p. :1184.

- [Google Scholar]

- The cytomorphologic spectrum of small-cell carcinoma and large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma in body cavity effusions: A study of 68 cases. Cytojournal. 2011;8:18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sensitivity and specificity of immunohistochemical markers used in the diagnosis of epithelioid mesothelioma: A detailed systematic analysis using published data. Histopathology. 2006;48:223-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary small cell carcinoma of the stomach: A case report with an immunohistochemical and molecular genetic analysis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:524-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid transcription factor-1: Immunohistochemical evaluation in pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:5-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid transcription factor-1 is expressed in extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas but not in other extrapulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:238-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuroendocrine tumors of the gallbladder: An evaluation and reassessment of management strategy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:687-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Small-cell carcinoma of the gallbladder: Report of a case and literature review. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2011;4:135-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Small cell carcinoma of the gallbladder: Case report and comprehensive analysis of published cases. J Oncol. 2015;2015:304909.

- [Google Scholar]