Translate this page into:

The risk for malignancy using the Milan salivary gland classification categories: A 5-year retrospective review

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Aims:

Since the six-tier Milan salivary gland classification has been introduced, there are very limited studies in literature reporting the risk stratification of the Milan classification.

Methods:

We retrospectively classified a total of 285 salivary gland cytology cases into Milan reporting categories; there were 23 (8.1%) nondiagnostic, 48 (16.8%) nonneoplastic, 19 (6.7%) atypia of undetermined significance (AUS), 138 (48.4%) benign neoplasm, 13 (4.6%) neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential (NUMP), 8 (2.8%) suspicious for malignancy, and 36 (12.6%) malignant. Almost 110 cases (38.6%) had surgical follow-up resections.

Results:

The overall risk for malignancy (ROM) was 12.5% for AUS, 3.2% for benign neoplasm, 72.7% for NUMP, and 100% for the suspicious for malignancy and malignant. The ROM for nondiagnostic and nonneoplastic categories was not representative due to limited follow-up resections. The salivary cytology had sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of 93.0%, 100%, 100%, and 46.2% for neoplasm and 82.3%, 95.8%, 90.3%, and 92.0% for malignant.

Conclusion:

Our study supports the adaptation of the six-tier Milan classification for reporting salivary gland cytology, as well as emphasizing the utility of the NUMP category.

Keywords

Fine-needle aspiration

Milan classification

risk for malignancy

salivary gland

INTRODUCTION

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) has been widely used in the diagnosis of salivary gland lesions with generally good sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of salivary gland lesions.[12] Many salivary gland neoplasms show morphologic overlap, such as adenoid cystic carcinoma versus pleomorphic adenoma and low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma versus mucocele and mucinous metaplasia.[3] Reporting the cytology diagnosis is variable among individual pathologists and institutions, which can lead to miscommunications between pathologists and the operating surgeons. The six-tier Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology has been recently introduced with the support of the American Society of Cytopathology and the International Academy of Cytology with hopes of standardizing the reporting of salivary gland FNA.[4] One recent study with comprehensive review using the Milan reporting categories showed that the risk for malignancy (ROM) were nondiagnostic 25.0% ± 16.7%, nonneoplastic 10.2% ± 5.5%, benign neoplasm 3.4% ±1.3%, NUMP 37.5% ± 24.7%, suspicious for malignancy 58.6% ± 19.5%, and malignant 91.9% ±3.5%.[5] Another study reported the overall ROM to be 17.4% for nonneoplastic, 100% for atypical, 7.3% for benign neoplasm, 50% for NUMP, and 96% for positive for malignancy.[6] In the current study, we retrospectively reviewed and classified 285 cases of salivary gland cytology diagnosis using Milan reporting system based on the prior FNA diagnosis and calculated the ROM using the follow-up surgical resection histologic diagnosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School at Houston. All salivary gland FNAs were performed by either head-and-neck surgeons or interventional radiologists under ultrasound image guidance. The rapid on-site satisfactory evaluation was provided by cytopathologists. The air-dried slides with Diff-Quik staining were used for on-site evaluation, and the mirror slides fixed in alcohol/cytolyt solution were stained with Papanicolaou stain for permanent review. A cellblock or cytospin might be prepared using the needle washing depending on the quantity of needle washing material. The FNA reports from salivary gland lesions during January 2011–March 2017 were retrieved, and the cytology diagnosis was retrospectively classified into the Milan categories based on the previous FNA reports and the case comments. The cytological categories based on the Milan reporting system included nondiagnostic (category 1), nonneoplastic (category 2), atypia of undetermined significance (AUS) (category 3), benign neoplasm (category 4a), neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential (NUMP, category 4b), suspicious for malignancy (category 5), and malignant (category 6). The corresponding surgical pathology reports of follow-up resections were reviewed, and cytology–histology correlation was performed. The sensitivity, specificity, positive, negative predictive value, accuracy, and risk of malignancy were calculated.

RESULTS

A retrospective review of salivary gland FNA specimens over a period of 5 years was performed with a total of 285 cases. The age of the patients ranged from 2 to 91 years, and the mean age was 56.1 years. There were only three cases in young patients, one 2-year-old boy, one 15-year-old boy, and one 15-year-old girl. The procedure for the 2-year-old patient was performed in operation room with general anesthesia, and the two 15-year-old patients had procedure done by interventional radiology with local anesthesia. The male-to-female ratio was 0.67:1. The FNA sites included the parotid gland (257, 90.2%), submandibular gland (22, 7.7%), and other sites (6, 2.1%).

A cytopathologist (SZ) carefully reviewed both the prior cytology diagnosis and the case comments, and the 285 cases were classified into the six-tier Milan categories as nondiagnostic 23 (8.1%), nonneoplastic 48 (16.8%), AUS 19 (6.7%), benign neoplasm 138 (48.4%), NUMP 13 (4.6%), suspicious for malignancy 8 (2.8%), and malignant 36 (12.6%). The follow-up surgical resections were available in 110 cases, and the cytology–histology correlation was performed [Table 1]. The initial cytology diagnosis and the Milan reclassification were tabulated in Table 2. The overall ROM was 12.5% for AUS, 3.2% for benign neoplasm, 72.7% for NUMP, and 100% for the suspicious for malignancy and malignant. The nondiagnostic and nonneoplastic categories had limited surgical follow-up cases (4 and 5 cases, respectively), and the ROM was 50% for nondiagnostic and 60% for nonneoplastic.

| Milan categories | Number of cytology cases | Number of cases with surgical follow-up | Number of cases to be benign neoplasm | Number of cases positive for malignancy, n (%) | Malignant diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Nondiagnostic | 23 | 4 | 1 | 2 (50) | Acinic cell carcinoma |

| Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma | |||||

| 2. Nonneoplastic | 48 | 5 | 1 | 3 (60) | Squamous cell carcinoma, extranodal MALT lymphoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma |

| 3. AUS | 19 | 8 | 2 | 2 (25) | Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, large B-cell lymphoma |

| 4a. Benign neoplasm | 138 | 62 | 60 | 2 (3.2) | Basal cell adenocarcinoma |

| Acinic cell carcinoma | |||||

| 4b. NUMP | 13 | 11 | 3 | 8 (72.7) | High-grade carcinoma, NOS (2), acinic cell carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma (2), salivary duct carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma (2) |

| 5. Suspicious for malignancy | 8 | 4 | 0 | 4 (100) | Acinic cell carcinoma (2), metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma |

| 6. Malignant | 36 | 16 | 0 | 16 (100) | Adenoid cystic carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma (4), salivary ductal carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma (2), carcinosarcoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma (3), melanoma, malignant hematolymphoid neoplasm, B-cell lymphoma (2) |

| Total | 285 | 110 | 68 | 36 |

AUS: Atypia of undetermined significance, NUMP: Neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential, MALT: Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, NOS: Not otherwise specified

| The original cytology diagnosis | The Milan reclassification |

|---|---|

| Scant/unsatisfactory/nondiagnostic (21) cystic contents only (2) | Unsatisfactory (Milan category 1) |

| Negative (14), granulomatous inflammation (3), acute inflammation (7), mixed lymphoid tissue (11), benign salivary tissue (6), lymphoepithelial cyst (1), cystic contents with benign epithelial cells (5), lipoma (1) | Negative for malignancy (Milan category 2) |

| Scant atypical squamous cells (4), scant atypical cells (5), oncocytic cells with background necrosis (2), scant basaloid cells (2), atypia suspicious for neoplasm (3), atypical lymphoid tissue (2), extensive necrosis, indeterminate (1) | AUS (Milan category 3) |

| Pleomorphic adenoma (78), Warthin tumor (45), oncocytic neoplasm, favor benign (5), cellular pleomorphic adenoma (7), pleomorphic adenoma with extensive squamous metaplasia (1), schwannoma (1), benign salivary neoplasm (1) | Benign neoplasm (Milan category 4a) |

| Neoplasm of uncertain malignant (1), cannot rule out carcinoma (2), cannot rule out lymphoma (1), myoepithelial tumor (1), cystic papillary neoplasm (2), biphasic salivary neoplasm (1), basaloid neoplasm, favor low-grade tumor (1), mucinous cells and mucus, cannot rule out mucoepidermoid carcinoma (1), basaloid neoplasm (2), atypical oncocytic neoplasm (1) | NUMP (Milan category 4b) |

| Suspicious for squamous carcinoma (1), favor acinic cell carcinoma (1), suspicious for lymphoma (3), suspicious for metastatic breast carcinoma (1) | Suspicious for malignancy (Milan category 5) |

| Squamous carcinoma (11), acinic cell carcinoma (3), mucoepidermoid carcinoma (4), adenoid cystic carcinoma (3), lymphoma (9), high-grade carcinoma (3), malignant neoplasm, NOS (1), salivary ductal carcinoma (1), metastatic melanoma (1) | Positive for malignant (Milan category 6) |

AUS: Atypia of undetermined significance, NUMP: Neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential, NOS: Not otherwise specified

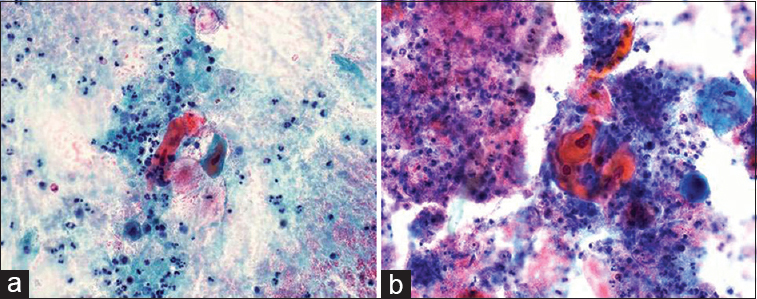

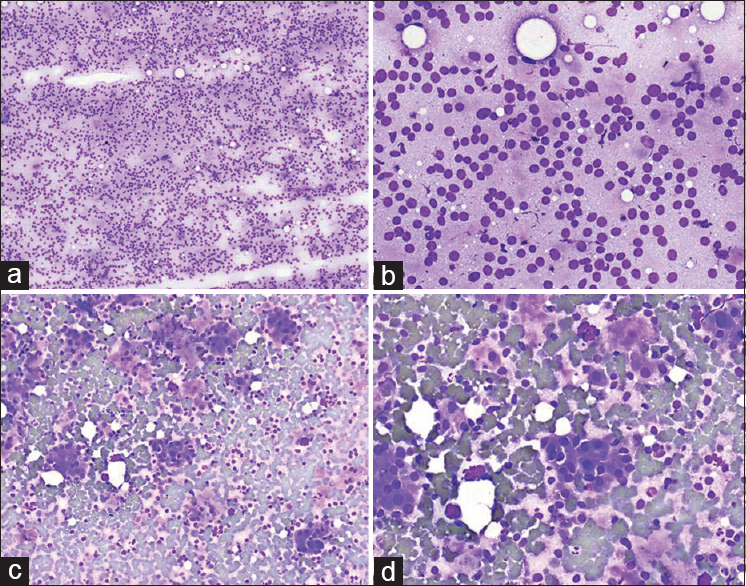

There were no false-positive cases in our study, but there were eight false-negative cases. Scant cellularity/poor sampling accounted for 3/8 false-negative cases, and 5/8 cases were misinterpretations. One example of scant material from a parotid cystic mass showed abundant inflammatory debris and very rare atypical squamous cells [Figure 1a and b]. The cytopathologist did not notice the rare atypical squamous cells and made diagnosis of negative with inflammation, and the surgical resection was a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. One example of misinterpretation from a parotid gland mass showed numerous single cells [Figure 2a and b], and clusters/sheets of epithelioid cells with background lymphoid-like cells [Figure 2c and d]. The cytopathologist misinterpreted the single cells as lymphocytes and made a diagnosis of oncocytic neoplasm, favor Warthin tumor. However, the single, lymphoid-like cells were actually numerous naked nuclei and some with prominent nucleoli, which are the classic cytomorphology of acinic cell carcinoma. The follow-up surgical resection was acinic cell carcinoma.

- The smears from a 91-year-old male patient with a left parotid cystic mass showed abundant debris, inflammation, and rare atypical squamous cells with deep orangeophilic cytoplasm (a and b, Papanicolaou, ×400). The primary pathologist interpreted the smears as “inflammation and negative.” The follow-up surgical resection was well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma

- The smears from a 44-year-old male patient with a right parotid mass showed cellular smears with mostly single cells (a: Diff-Quik, ×100; b: Diff-Quik, ×400). Other areas of the smears showed some clusters of epithelial cells (c: Diff-Quik, ×100; d: Diff-Quik, ×400). The primary pathologist misinterpreted the background single cells as lymphocytes and misdiagnosed as “oncocytic neoplasm, favor Warthin tumor.” The follow-up surgical resection was acinic cell carcinoma

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of salivary gland cytology were calculated. For diagnosis of neoplastic lesions, Milan categories 2 and 3 were considered negative cytology and Milan categories 4a, 4b, 5, and 6 were considered as positive cytology. FNA had a sensitivity of 93.0%, specificity 100%, PPV 100%, and NPV 46.2% for the diagnosis of salivary gland neoplasm. For diagnosis of malignant neoplasm, Milan categories 2, 3, and 4a were considered negative cytology, and Milan categories 4b, 5, and 6 were considered positive cytology. FNA had a sensitivity of 82.3%, specificity 95.8%, PPV 90.3%, and NPV 92.0% for the diagnosis of salivary gland malignant neoplasm. Milan category 4b had significant higher risk of malignancy than Milan category 4a (72.7% vs. 3.2%, P < 0.00001).

DISCUSSION

The six-tier classification scheme, Milan categories for FNA salivary cytology, was recently introduced.[4] While the Milan classification scheme has traditional cytology categories, it also addresses the difficulties and challenges in salivary gland cytology diagnosis by adding a category of neoplasm of uncertainmalignant potential (NUMP). The NUMP category can be used for neoplastic lesions that are difficult to differentiate between benign and malignant. Using a standardized cytology reporting system, such as the Milan reporting classification scheme, pathologists can improve the communication with surgeon and the risk formalignant (ROM) stratification. Our data showed ROM 12.5% for atypical, 3.2% for benign neoplasm, 72.7% for NUMP, and 100% for the suspicious for malignancy and malignant. The ROM from our study for nondiagnostic (50%) and nonneoplastic (60%) was likely not representative due to very limited cases (4 and 5, respectively) in our study. In the literature, the nondiagnostic category had ROM 25.0% ± 16.7%,[4] and the nonneoplastic category had ROM 10.2% ± 5.5% and 17.4%.[56] The ROM for atypical category was studied including five tertiary medical centers, and the ROM varied from 73.08% to 0.00%.[7] The study concluded that “the highly variable ROM (of atypical category) among different institutions likely reflects practice at each individual institution.” The atypical category needs further clarification to achieve some uniformity among all cytopathologists. The ROM of benign neoplasm category was generally low, from 3.4% ±1.3% to 7.3%,[56] similar to our result of 3.2%. The very low ROM in benign neoplasm category indicates the well-defined cytomorphological features and the accurate cytology diagnosis of most benign neoplasms. The NUMP category had ROM 37.5% ± 24.7% and 50%,[56] and we had ROM of 72.7%. Our data and other studies clearly demonstrated the significant different ROMs between benign neoplasm and NUMP. The suspicious for malignancy category had ROM 58.6% ± 19.5% and 83.3%,[58] and positive for malignancy had ROM 91.9% ± 3.5% and 96%.[56] The suspicious for malignancy category was relatively homogenous, and there was no significant variability worldwide.[8]

Studies have shown the utility of FNA cytology in providing valuable information to appropriately manage salivary gland lesions and prevent unnecessary invasive procedures of nonneoplastic lesions.[91011] Our study showed that the FNA salivary cytology had sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 93.0%, 100%, 100%, and 46.2% for the diagnosis of salivary neoplasm and 82.3%, 95.8%, 90.3%, and 92.0% for the diagnosis of malignant salivary neoplasm. However, the difficulties and challenges on FNA salivary gland cytology have also been well documented. The study based on the College of American Pathologists (CAP) nationwide survey showed a significant false-positive diagnosis on some benign neoplasms and significant false negative on some malignant neoplasms.[12] Based on the CAP study, benign cases with the highest false-positive rates were monomorphic adenoma (53% false positive), intraparotid lymph node (36%), oncocytoma (18%), and granulomatous sialadenitis (10%). Malignant cases with the highest false-negative rates were lymphoma (57%), acinic cell carcinoma (49%), low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma (43%), and adenoid cystic carcinoma (33%). The above CAP study had been criticized by scholars for sending only one representative slide and providing limited short history.[13] In the daily practice, the cytopathologists usually have some clinical and image findings and review multiple slides with Diff-Quik, Papanicolaou, and hematoxylin and eosin stains. Our study did not have false-positive cases, but the false-negative cases were low-grade B-cell lymphoma, acinic cell carcinoma, and low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Few cases of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma had false-negative cytology diagnosis due to scant and necrotic material. The experience of the cytopathologists on FNA salivary cytology can attribute to the diagnostic errors, but the cytomorphological overlap, prominent metaplasia, focal atypia, cystic changes, scant cellularity, and variants of neoplasms often caused the false diagnosis.[141516] In our study, we had 8 false-negative cases. Scant cellularity/poor sampling accounted for 3/8 false-negative cases, and 5/8 cases were misinterpretation due to different reasons such as the overlap cytomorphology, false-negative flow cytometry on low-grade lymphoma, and misinterpretation cell types on smears.

In summary, our study supports that the six-tier Milan classification system for reporting salivary gland FNA cytology should be used to provide a more standardized cytology report for accurate patient clinical management. The significant variation of ROM for atypical and NUMP categories among different studies indicates that further clarification and detailed description for these two categories are necessary.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors:

-

This study was presented at 2018 USCAP annual meeting;

-

the manuscript is not currently being considered for publication in another journal;

-

all authors have been personally and actively involved in substantive work leading to the manuscript, and will hold themselves jointly and individually responsible for its content.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

AUS - Atypia of undetermined significance

CAP - College of American Pathologists

FNA - Fine-needle aspiration

NPV - Negative predictive value

NUMP - Neoplasm of uncertainmalignant potential

PPV - Positive predictive value

ROM - Risk for malignancy.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- A systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of fine-needle aspiration cytology for parotid gland lesions. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:45-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sensitivity, specificity, and posttest probability of parotid fine-needle aspiration: A Systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:9-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Performance characteristics of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands in fine-needle aspirates: Results from the college of American pathologists nongynecologic cytology program. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:1525-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is it time to develop a tiered classification scheme for salivary gland fine-needle aspiration specimens? Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45:285-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reporting of Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) specimens of salivary gland lesions: A comprehensive review. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45:820-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Three-year cytohistological correlation of salivary gland FNA cytology at a tertiary center with the application of the Milan system for risk stratification. Cancer Cytopathol. 2017;125:767-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Atypical” salivary gland Fine-needle aspiration: Risk of malignancy and interinstitutional variability. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45:1088-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Suspicious” salivary gland FNA: Risk of malignancy and interinstitutional variability. Cancer Cytopathol. 2018;126:94-100.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic accuracy of Fine-needle aspiration cytology for high-grade salivary gland tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2380-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Salivary gland FNA cytology: Role as a triage tool and an approach to pitfalls in cytomorphology. Cytopathology. 2016;27:91-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration of salivary glands: 5-year experience from a single academic center. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:375-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pitfalls in salivary gland fine-needle aspiration cytology: Lessons from the college of American pathologists interlaboratory comparison program in nongynecologic cytology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:26-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pitfalls in salivary gland fine-needle aspiration cytology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1428.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic challenges and problem cases in salivary gland cytology: A 20-year experience. Cancer Cytopathol. 2018;126:101-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cystic lesions of the salivary glands: Cytologic features in fine-needle aspiration biopsies. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:197-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histopathologic and cytopathologic diagnostic discrepancies in head and neck region: Pitfalls, causes and preventive strategies. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:302-8.

- [Google Scholar]