Translate this page into:

Diagnostic importance of CD56 with fine-needle aspiration cytology in suspected papillary thyroid carcinoma cases

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Palpable thyroid nodules can be found in 4%–7% of the adult population; however, <5% of thyroid nodules are malignant. Immunohistochemical markers, such as CD56, can be used to make a differential diagnosis between benign and malignant lesions. To increase the accuracy of the diagnosis and distinguish the malignant aspirates from the benign ones, chose to evaluate CD56, which is normally found in benign thyroid tissue.

Methods:

A total of 53 fine-needle aspirate samples from patients diagnosed with suspected papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) were included prospectively. These aspirates were immunocytochemically stained for CD56.

Results:

In histopathological examination, the fine-needle aspiration cytopathology specimens suspicious for PTC (after undergoing surgery) showed that 32 (60.4%) were benign and 21 (39.6%) were malignant. Thirty-one of the benign cases (96.87%) were CD56-positive, whereas the last case (3.13%) was CD56-negative. Staining was not seen in any of the malignant cases.

Conclusions:

We believe that CD56 is an important marker in the definitive diagnosis of suspected PTC cases, with CD56-positivity being interpreted in favor of benignity.

Keywords

CD56

fine-needle aspiration cytology

immunocytochemistry

suspicion

thyroid carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Palpable thyroid nodules occur in 4%–7% of the adult population and 5% of these thyroid nodules are malignant.[1] Thefirst attempts at thyroid lesion diagnostics date back to 1939, when the TruCut (core needle) biopsy was tested, but only in 1960 did fine-needle aspiration (FNA) allow a noninvasive and quick suggestion of a diagnosis and assessment of the risk of malignancy, guiding patient management.[2] After the implementation of FNA into routine practice, the interpretation of the cytological images gradually improved, translating the pathologist's language into clinical recommendations. A still valid consensus was established in 2007, describing six diagnostic categories: nondiagnostic or unsatisfactory, benign, atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance, follicular neoplasm ((FN)/suspicious for a follicular neoplasm, suspicious for malignancy (SM) (suspicious for papillary carcinoma, medullary carcinoma, lymphoma, or other) and malignant.[34]

Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) is the most frequently seen histotype, with a prevalence ranging from 70% to 85% of all thyroid cancers.[5] The diagnosis of PTC in FNA specimens is usually unsophisticated when classic cytological features are present. However, in clinical practice, it is often difficult to make a clear cytological diagnosis of PTC. The diagnostic difficulties are related to the observation that some typical cytological features of PTC (nuclear grooves, giant cells, psammoma bodies, and papillary fragments) can also be observed in nonneoplastic lesions and FNs of the thyroid.[4]

However, there are limitations when using FNA cytology (FNAC) in thyroid nodules, and the literature reports a 3.7%–11% rate of suspicious cytological findings in FNAC.[678] Suspicious cytology runs the risk of histological malignancy in between 29% and 75% of the cases.[1] It is, therefore, current practice to perform a surgical excision using a diagnostic hemithyroidectomy for all cytologically suspicious thyroid nodules. If the final histology is malignant, the patient usually undergoes a completion of the thyroidectomy, given the risk to the parathyroid glands and recurrent laryngeal nerve when re-operating on the recently operated side.[910]

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was introduced to the practice of pathology in the early 1970s; however, its use is restricted in thyroid pathology. New techniques have been introduced to the thyroid FNA procedure to enhance its diagnostic value and improve its accuracy. During the past several years, many IHC markers have been tested in histological samples and to a lesser extent, in FNA samples with variable success rates. The evaluation of IHC markers has been performed most often in surgically resected thyroid specimens.[1112]

CD56 is a neural cell adhesion molecule that is present in the follicular epithelial cells of the normal thyroid.[13] Some researchers have made different interpretations of CD56 expression in benign and malignant thyroid lesions and have decided that it shows low or no expression in the IHC of PTC. A few studies have been conducted regarding the expression of CD56 in thyroid lesions, but there has been only one study about the expression of CD56 in FNAC.[51314]

According to the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology described by Cibas et al., several criteria have been used for the inclusion of suspicious PTCs: increased cellularity, an enlarged nucleus, nuclear grooving or molding, membrane irregularity, intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions, nuclear clearing, a prominent nucleolus, the presence of papillary structures, and an association with normal follicular cells. Although we have used these criteria in our clinic, most of the histopathological results of the FNACs of the cases diagnosed with a suspicion of PTC were benign thyroid lesions. The percentage of PTC suspicious cases is higher in the FNAC than in the literature, while the percentage of PTCs in the histopathological examination of these cases is lower than that of the literature. Therefore, to increase the accuracy of a FNAC diagnosis and reduce personal diagnostic errors, we chose to use CD56, which is normally found in benign thyroid tissue, for the differential diagnosis. The results are presented below.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the local ethics committee and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

A total of 365 FNAC samples were stained with Papanicolaou (Pap) and May-Grünwald Giemsa (MGG) and examined based on the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology criteria (as described above). In total, 53 cases that were diagnosed with suspicious PTC were included in this research.[3] In our hospital, the FNAC is done by radiologists; the aspirates are spread on a slide, and they are sent to the pathology laboratory. In our pathology laboratory, some of these slides are routinely stained with MGG and Pap. At least one of these slides was divided, without immunocytochemistry (ICC). The CD56 staining was performed using ICC on the nonstaining aspirates of the suspicious cases. These divided slides were air-dried and unfixed, and the ICC was performed using a Leica BOND-MAX automated staining device. The slides were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with the primary CD56 antibodies (mouse, clone 123C3. D5, dilution 1:50-1:100; Thermo Scientific, Fremont, CA, USA). The reaction was developed using 3-3'diaminobenzidine. All of the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin for 5 s, rinsed with water 3 times, and examined through light microscopy based on the membranous staining. The scores were negative (<%20) and positive (>%20). The thyroidectomy materials of these cases were examined by the same pathologist who determined the histopathological diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A normalization assumption was used. Since the mode, median, and mean values calculated for all of the parameters were close to each other, all of the data were accepted as normally distributed. Because there were several subgroups of variables, a Chi-squared cross-tab analysis was performed to determine the possible correlations and statistically significant differences. A point-double series correlation analysis was used to determine the direction of the correlation.

RESULTS

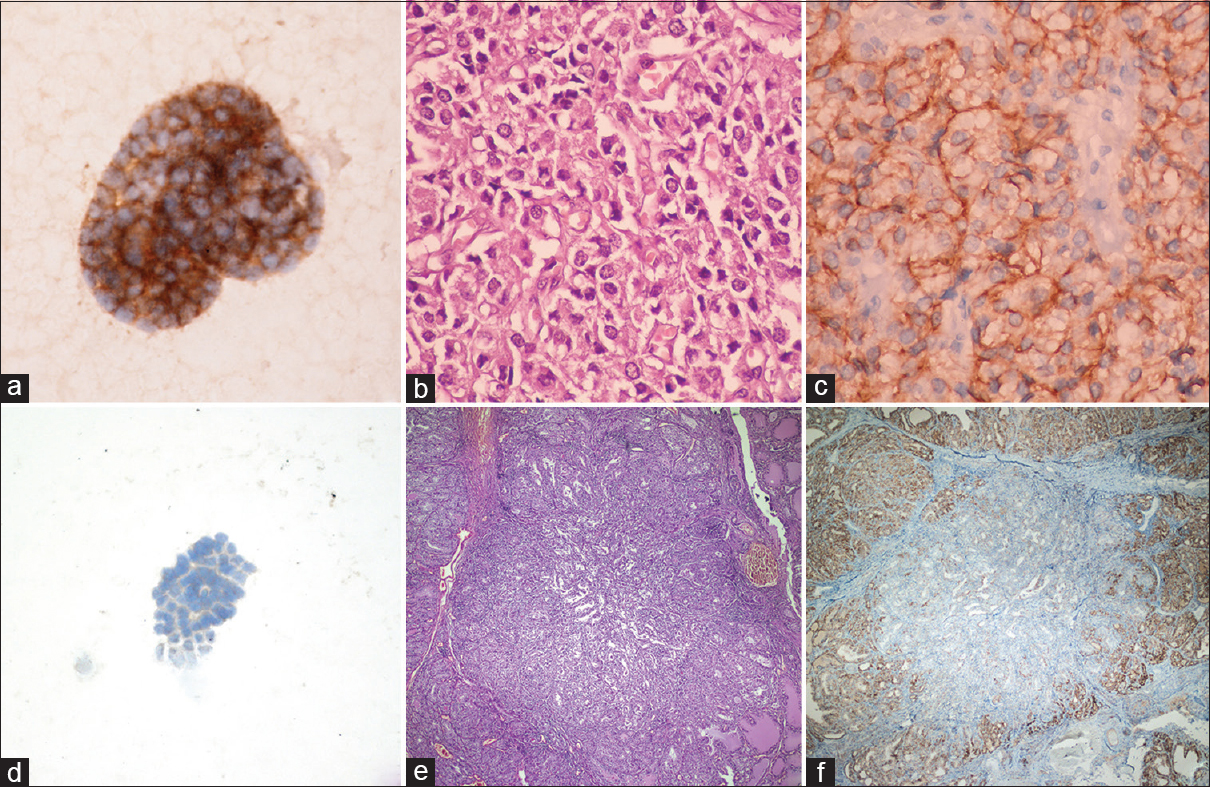

The mean age of the patients was 48 years old (range: 24–74); 77.4% (n = 41) were female and 22.6% (n = 12) were male. The IHC results of the aspirates showed that 31 of the cases (58.49%) were CD56-positive and 22 of the cases (41.51%) were CD56-negative. The CD56 staining exhibited a membranous pattern in all of the cases [Figure 1].

- (a) Detail of membranous CD56 positivity in a suspected cytology diagnosed adenomatoid nodule (avidin-biotin-peroxidase, ×400); (b) Histopathologic section of adenomatoid nodule (H and E, ×400); (c) Membranous CD56 expression on histological sample of same cases (avidin-biotin-peroxidase, ×400); (d) CD56 negative staining in suspected cytology (avidin-biotin-peroxidase, ×400); (e) Histopathologic section of same case diagnosed papillary carcinoma (H and E, ×100); (f) CD56 positive in normal tissues and negative staining in papillary carcinoma (avidin-biotin-peroxidase, ×100)

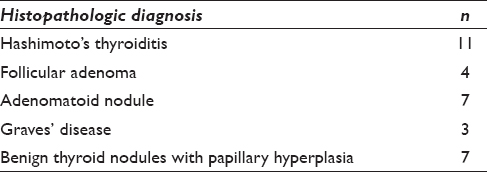

The histopathological examination of the FNAC specimens from those cases that were PTC suspicious and underwent surgery showed that 32 (60.4%) were benign and 21 (39.6%) were PTCs. Eleven of the cases were diagnosed with Hashimoto's thyroiditis, 4 were diagnosed with follicular adenomas, 7 were diagnosed with adenomatoid nodules, 3 were diagnosed with Graves' disease and 7 were benign thyroid nodules with papillary hyperplasia [Table 1]. One case with a CD56-negative staining aspirate was histopathologically diagnosed as a benign thyroid nodule with papillary hyperplasia.

The results of the statistical analysis showed that the rate of CD56 staining in the benign cases was significantly different from the rate of CD56 staining in the malignant cases (P < 0.01). The sensitivity was 96.9%, the specificity was 100%, the positive predictive value was 100%, and the negative predictive value was 96.87%. In the thyroidectomy materials, CD56 showed negative staining in all of the PTCs (n = 21) and positive staining in all of the benign cases.

DISCUSSION

FNAC is regarded as the gold standard in the initial diagnosis of thyroid nodules. It is simple, reliable, time-saving, minimally invasive, and cost-effective;[1516] however, there are some limitations of which a pathologist must be aware.[17181920] The main strength of FNAC is its ability to distinguish a malignant lesion from a benign one. This distinction has dramatically reduced the surgery rates in thyroid pathologies in recent years.[21] Although the accuracy rates have been reported to be as high as 95%–98% in an expert's hand, FNAC does have some limitations, yielding both false-positive and false-negative results.[16] Chen et al.[22] showed that FNAC could be solely reliable for the diagnosis of PTCs with a specificity of up to 98%.

The cytological diagnosis of a PTC is difficult when the classical features are absent or focally present.[232425] When a cytological smear shows only some of the features, a PTC suspicious diagnosis is recommended.[1026] The morphological similarities between benign hyperplastic papillary lesions and PTCs can be seen, causing diagnostic errors in both FNACs and histological specimens. Moreover, Hashimoto's thyroiditis may induce nuclear atypia, chromatin clearing, and even nuclear grooves, which may lead to an incorrect diagnosis.[5] There are also some personal evaluation mistakes that can be made, and the goal of our study was to eliminate these.

During the past several years, a large number of IHC markers have been tested in histological samples and FNA samples, to a lesser extent, with variable success rates. The evaluation of IHC markers has been performed most often in surgically resected thyroid specimens. However, similar studies have also been done on FNAC specimens. In general, the previous research has shown similar marker expression results when comparing the surgical specimens and FNAs. Many IHC markers have been investigated for the evaluation of thyroid nodules; however, only a few markers have emerged as being potentially useful for differentiating between benign and malignant thyroid nodules.[27] Hector Battifora Mesothelial Cell-1 (HBME-1), Galectin-3 (Gal-3) and Cytokeratin-19 (CK19) have been the most frequently used antibodies in thyroid pathology, but there are different studies reported a wide range of sensibility and specificity values of these markers. Because of this range, these markers cannot be used only alone. They are usually used in the panel.[28]

The neural cell adhesion molecule or CD56 is a homophilic membrane glycoprotein. It is an adhesion molecule from the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily that is expressed normally on the surface of neurons, glia, skeletal muscle cells, and natural killer cells. CD56 expression (both protein and mRNA) has also been confirmed in thyroid follicular epithelial cells and adrenal glands and undergoes membranous staining in the follicular epithelial cells. A reduction in its expression has been previously reported in PTCs.[28]

Based on the FNAC results of this study, 31 of the benign cases (96.87%) were CD56-positive, and the last one (3.13%) was CD56-negative. Staining was not seen in any of the malignant cases (n = 21). CD56 was identified as a highly specific (100%) marker when distinguishing malignant from benign. Unlike this study, Bizzarro et al.[5] reported a series of 85 thyroid cases (including both nonneoplastic and PTC), in which CD56 was expressed in 24 benign lesion cases and 2 PTC cases. It was negative in 48 of the PTC cases and 11 of the benign lesion cases (sensitivity 96%, specificity 69%). Scarpino's stud[14] reported that CD56 staining was not seen in any of the benign lesions, which was similar to our study, but in the presented case, CD56 staining was not observed in one benign case (sensitivity 96.9%). In addition, Park et al.[29] studied CD56 IHC in thyroid carcinomas and benign thyroid nodules, and saw no staining with CD56 in 92.5% of the PTC cases. In a study by El Demellawy et al.[30] both the sensitivity and specificity were 100% for CD56 expression in distinguishing PTCs from other thyroid follicular lesions. According to Bizzarro et al., this different range of positivities may be related to the quantitative evaluation of the membranous and/or cytoplasmic CD56 positivity. That is, they may have been considered positive for cytoplasmic staining. Like many writers, we are also convinced that CD56 was determined to be the most sensitive marker.[2831] Whereas, any of the routinely used markers (HBME-1, Gal-3, CK19) have not 100% specificity and sensitivity.[3132]

One case with a CD56-negative staining aspirate was histopathologically diagnosed as a benign thyroid nodule with papillary hyperplasia in this study. The papillary structures were seen quite frequently in this case, but with the exception of pleomorphism, the other criteria were not found. Although a thyroid FNA biopsy is highly accurate for the diagnosis of PTC, papillary hyperplasia may be misdiagnosed as suspicious for PTC.[3334] Therefore, the results of these cases were reviewed again, and poor staining was seen on some of the cell membranes. However, this staining was below 20%.

Previous studies have proven that CD56 is a highly promising immunomarker. In the studies by Scarpino et al. and Abd El Atti and Shash, CD56 exhibited a high specificity when used alone or in an immunopanel,[142430] but 100% specificity was not detected in either of the studies.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, we sought to ascertain the efficacy of CD56 for discriminating between benign and malignant thyroid FNAC specimens. We believe that CD56 is an important marker in the definitive diagnosis of cases suspicious for PTC. CD56-positivity can be interpreted in favor of benignity and reduce the rate of suspected PTC diagnoses, thereby reducing the rate of unnecessary surgical interventions.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Manuscript written by correspond author.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This report was approved by Elazıǧ regional ethics committee (2016, 4/11).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic Order)

FNA - Fine needle aspiration

FNAC - Fine needle aspiration cytology

ICC - Immunocytochemically

IHC - Immunohistochemistry

PTC - Papillary thyroid carcinoma.

EDITORIAL/PEER REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I would like to thank my sister Selma Akyol and to Dr. Ahmet Kılıçaslan who helped me during the data collection phase.

REFERENCES

- Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the thyroid: An appraisal. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:282-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the thyroid gland. In: De Groot LJ, Beck-Peccoz P, Chrousos G, eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth(MA): MDText.Com, Inc; 2000.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:658-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic terminology and morphologic criteria for cytologic diagnosis of thyroid lesions: A synopsis of the national cancer institute thyroid fine-needle aspiration state of the science conference. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:425-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of CD56 in thyroid fine needle aspiration cytology: A Pilot study performed on liquid based cytology. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132939.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration cytology of the thyroid. A 12-year experience with 11,000 biopsies. Clin Lab Med. 1993;13:699-709.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of fine-needle aspiration cytology in the surgical management of thyroid cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:827-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the thyroid. The problem of suspicious cytologic findings. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:25-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology: A meta-analysis. Acta Cytol. 2012;56:333-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preoperative evaluation and predictive value of fine-needle aspiration and frozen section of thyroid nodules. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:494-502.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic efficacy of immunocytochemistry on fine needle aspiration biopsies processed by thin-layer cytology. Acta Cytol. 2006;50:129-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunocytochemical evaluation of thyroid neoplasms on thin-layer smears from fine-needle aspiration biopsies. Cancer. 2005;105:87-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expression of CD56 (NKH-1) differentiation antigen in human thyroid epithelium. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;89:474-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Papillary carcinoma of the thyroid: Low expression of NCAM (CD56) is associated with downregulation of VEGF-D production by tumour cells. J Pathol. 2007;212:411-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accuracy of fine-needle aspiration of thyroid. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:484-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration cytology of the thyroid: An appraisal. Cancer. 2000;90:325-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of the thyroid: A comparison of 5469 cytological and final histological diagnoses. Cytopathology. 2006;17:245-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study of cyto-histological correlation in the diagnosis of thyroid swelling. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2014;13:46-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid nodule: Cytohistological correlation. Scholar J Appl Med Sci. 2013;1:745-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histologic analysis and comparison of techniques in fine needle aspiration-induced alterations in thyroid. Acta Cytol. 2008;52:56-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodules: Correlation between cytology and histology and evaluation of discrepant cases. Cancer. 1997;81:253-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Papillary carcinoma of the thyroid: Can operative management be based solely on fine-needle aspiration? J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184:605-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytopathology of papillary carcinoma of the thyroid by fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 1980;24:511-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aspiration Biopsy: Cytologic Interpretation and Histologic Bases. New York: Igaku-Shoin Medical Publishers, Inc; 1984. p. :169-70.

- Nuclear grooves in the aspiration cytology of papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. Acta Cytol. 1989;33:21-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The national cancer institute thyroid fine needle aspiration state of the science conference: A summation. Cytojournal. 2008;5:6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunohistochemical expression of HBME-1, E-cadherin, and CD56 in the differential diagnosis of thyroid nodules. Medicina (Kaunas). 2012;48:507-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic value of HBME-1, CD56, galectin-3 and cytokeratin-19 in papillary thyroid carcinomas and thyroid tumors of uncertain malignant potential. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:49-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic value of decreased expression of CD56 protein in papillary carcinoma of thyroid gland. Basic Appl Pathol. 2009;2:63-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic utility of CD56 immunohistochemistry in papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. Pathol Res Pract. 2009;205:303-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of cd56 and e-cadherin expression in the differential diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma and suspected follicular-patterned lesions of the thyroid: The prognostic importance of e-cadherin. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:3670-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- CD56, HBME-1 and cytokeratin 19 expressions in papillary thyroid carcinoma and nodular thyroid lesions. J Res Med Sci. 2016;21:49.

- [Google Scholar]

- FNAB of benign thyroid nodules with papillary hyperplasia: A cytological and histological evaluation. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122:666-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Potential diagnostic utility of CD56 and claudin-1 in papillary thyroid carcinoma and solitary follicular thyroid nodules. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2012;24:175-84.

- [Google Scholar]