Abdominal lymphadenopathy: An interesting and rare case diagnosed on endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

A 68-year-old woman presented to a gastroenterologist with abdominal pain, loss of appetite, and significant weight loss for last 5–6 months. Her history revealed that she had been having recurrent episodes of abdominal pain for last 15 years with postprandial distension and vomiting. She had taken two courses of anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) in the past. These were probably given empirically as no tissue diagnosis was available. She had been investigated extensively in another hospital for her present complaints; however, no diagnosis could be made. Computed tomography scan done outside revealed multiple calcified and noncalcified lymph nodes in the axilla, chest, and abdomen, and healed calcified foci in liver and spleen. There were fibro-calcified lesions in bilateral upper lobes of the lung. There was also mild ascites and bilateral pleural effusions. Physical examination revealed pallor, pedal edema, basal crepitation, and hepatomegaly. She had albuminuria, and 24 h urinary protein levels were raised. Her echocardiography revealed mild pulmonary arterial hypertension. She underwent endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of the abdominal lymph nodes with a clinical suspicion of tuberculosis. The EUS-FNA was performed using 22 G needle from the peri-pancreatic lymph nodes [Figures 1 and 2].

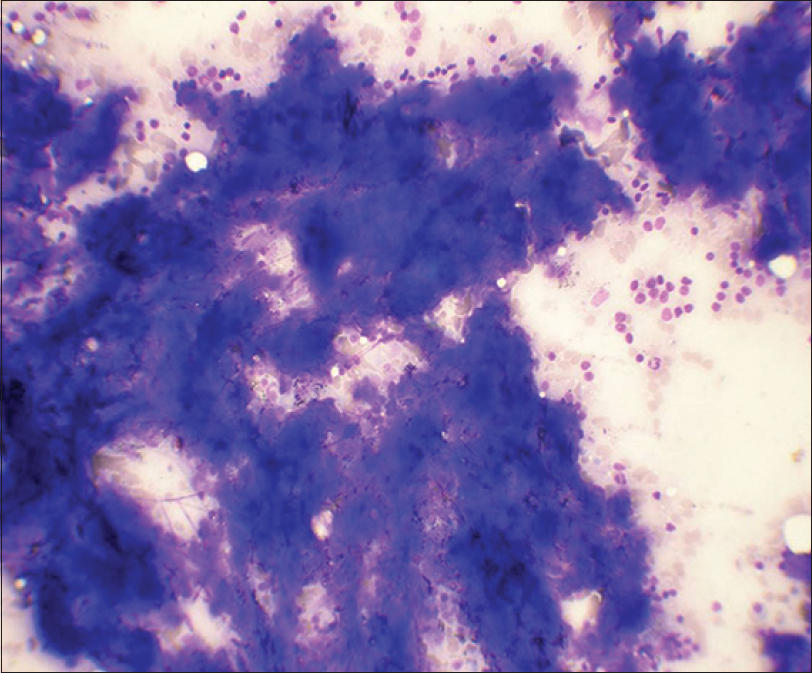

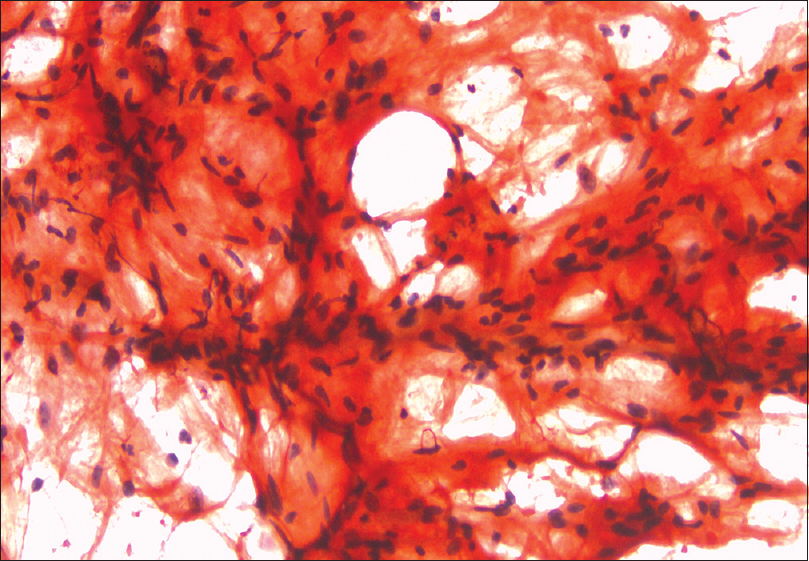

- Fine needle aspiration smears of lymph node show basophilic clumps of acellular, homogenous material. Few lymphoid cells are also observed (May-Grunwald-Giemsa, ×400)

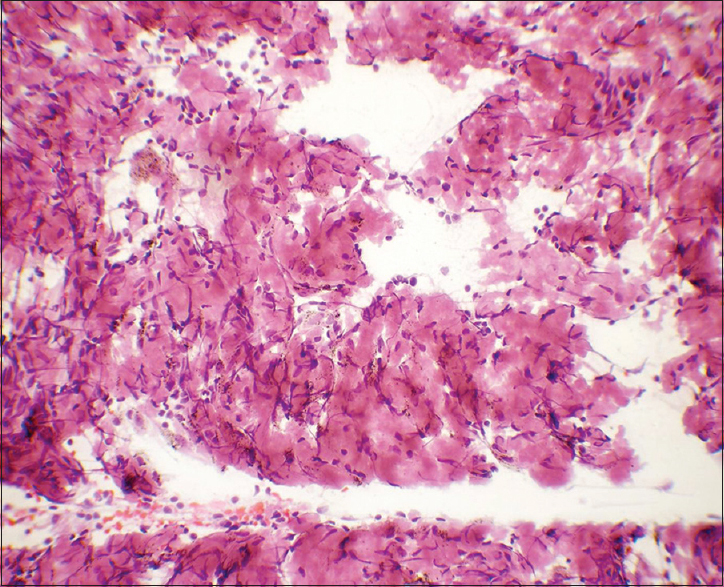

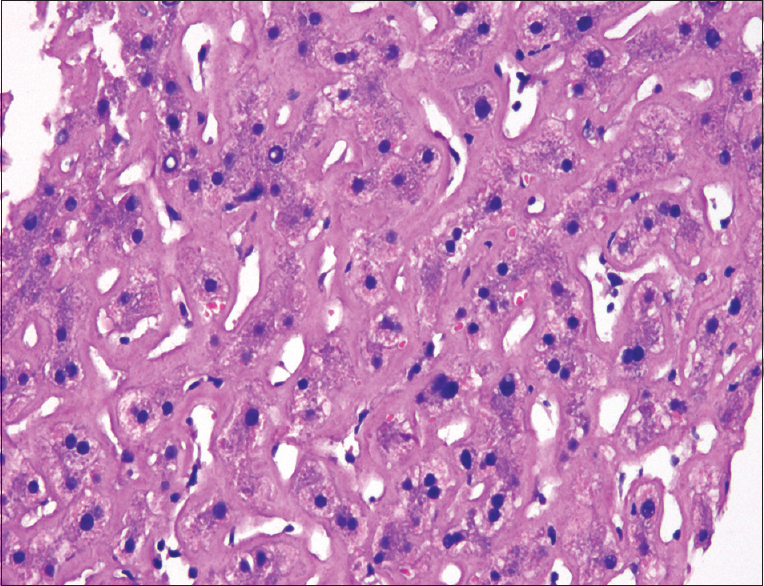

- Flocculent material was eosinophilic in Papanicolaou stain. Many spindle stromal cells were seen haphazardly intermixed with it (×400)

QUESTION: WHAT IS YOUR INTERPRETATION AND WHICH SPECIAL STAIN WOULD YOU DO?

-

Necrosis, Ziehl–Neelsen (ZN) stain

-

Para-amyloid, periodic acid-Schiff stain

-

Amyloid, Congo red stain

-

Mucin, Mucicarmine stain.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation and special stain is:

c: Amyloid, Congo red stain

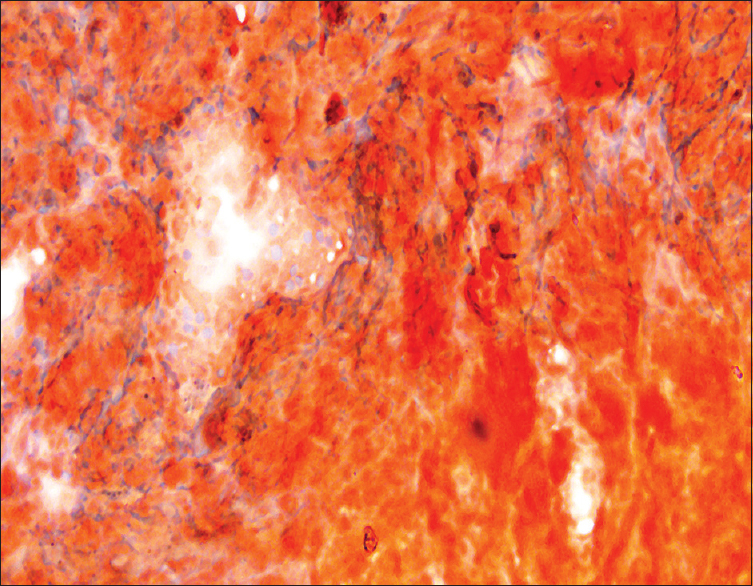

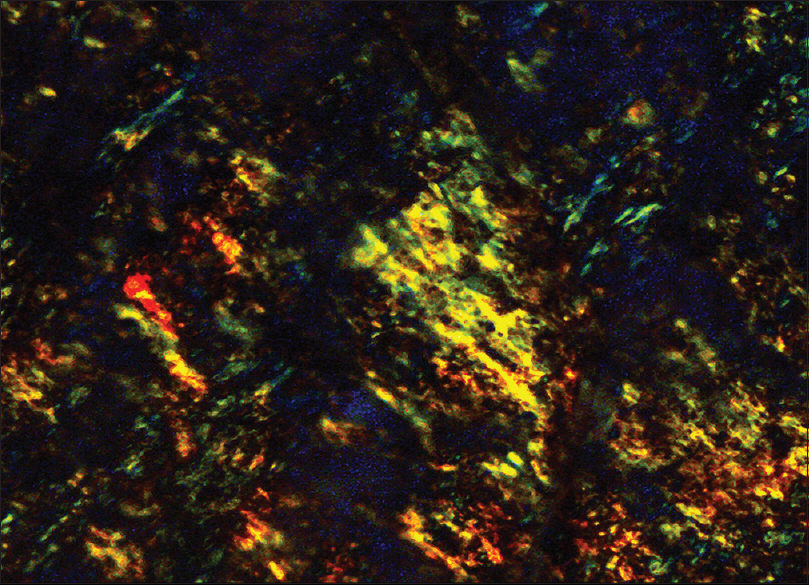

In cytology smears, amyloid is seen as flocculent material associated with connective tissue cells. It stains cyanophilic to eosinophilic on Papanicolaou stain and deep blue on May-Grunwald-Giemsa stain.[1] The characteristic apple green birefringence after Congo red staining under polarized light is sufficient for diagnosis[2] [Figures 3 and 4].

- Congo red staining on lymph node smears (×400)

- Apple green birefringence under polarized light, Congo red staining, lymph node (×400)

ADDITIONAL QUIZ QUESTIONS

Q1: The differential diagnoses of amyloid in cytology smears in clinically suspected cases would depend upon

-

Organ involved

-

Chemical nature of amyloid.

Q2: Which of the following could be difficult to differentiate from amyloid in lymph nodes without the aid of Congo red stain?

-

Caseous necrosis

-

Para-amyloid

-

Protein deposition in angiocentric sclerosing lymphadenopathy

-

All the above.

Q3: Amyloid lymphadenopathy is most commonly seen

-

As a part of systemic amyloidosis

-

In lymphoproliferative disorders

-

As localized amyloidosis.

ANSWERS TO ADDITIONAL QUESTIONS

Q1: (a); Q2: (d); Q3: (a)

-

There are few short series and scattered case reports describing amyloid in cytology specimens in various organs. Amyloidosis has been reported in FNA smears from thyroid, lymph nodes, bones, lungs, liver, and soft tissues. It has been occasionally reported in exfoliative cytology specimens of bronchial washings and urine.[1234] Diagnosis of amyloid protein in cytology smears in the absence of clinical suspicion is challenging and includes various differentials based on the organ involved. Amyloid may be overlooked as colloid in thyroid. In respiratory specimen, it can mimic a number of extracellular substances including mucus, alveolar proteinosis, and chondroid material or corpora amylacea. In aspirates from bone, amyloid may be indistinguishable from osteoid[1]

-

There are few instances in literature in which amyloid deposition has been misdiagnosed as tuberculosis in various organs. In a case reported by Michael and Naylor, the presence of amyloid in a background of multinucleated giant cells in an aspirate from subcutaneous soft tissue led to preliminary diagnosis of necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. Giant cells may also be present as a reaction to amyloid.[1] Amyloid deposits in a case of liver FNA cytology (FNAC) were interpreted as hyalinized granuloma.[5] Amorphous granular basophilic material was mistaken as caseous necrosis in Giemsa-stained smears of a lymph node aspirate, and diagnosis of tuberculous lymphadenitis was suggested.[6] Necrotizing granulomatous lymphadenitis is a commonly rendered diagnosis in our setting.[7] According to our observation:

-

Amyloid had a more flocculent appearance as compared to the “spread out” character of caseous necrosis [Figure 1]

-

The amyloid deposits had well-defined borders in many foci which are not a feature of necrosis [Figure 2]

-

The amyloid had smooth and glassy texture as compared to the granular nature of caseous necrosis and this was better highlighted in Papanicolaou-stained smears [Figure 2]

Besides caseous necrosis, other differential diagnoses in lymph node would include protein deposition in angiocentric sclerosing lymphadenopathy and deposition of para-amyloid. Para-amyloid is seen in lymph nodes with angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy, Hodgkin's disease, or due to iatrogenic causes.[8] The characteristic, apple green birefringence on Congo red staining under polarized light distinguishes it from para-amyloid, other proteins, and necrosis.[2]

-

-

Amyloid lymphadenopathy is usually seen as a part of systemic amyloidosis or less commonly in lymphoproliferative disorders.[8] Lymph node involvement occurs in up to 37% of patients with systemic amyloidosis. Hilar, mediastinal, and para-aortic lymph nodes are most commonly involved. Localized primary amyloidosis presenting as lymphadenopathy has also been rarely reported in literature.[9]

BRIEF REVIEW OF THE TOPIC

Diagnosis of amyloid lymphadenopathy was rendered on FNAC. No granuloma or atypical cells were observed in the smears. ZN staining for acid-fast bacilli was negative.

For confirmation of amyloidosis, the patient also underwent abdominal fat pad FNAC and liver biopsy. Abdominal fat pad aspiration is a relatively noninvasive, low-cost method for obtaining tissue to diagnose systemic amyloidosis. Cell block preparation, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy improve the detection of amyloid in fat pad aspiration.[10]

The abdominal fat pad aspiration smears showed linear deposits of amyloid on Congo red staining [Figure 5]. These showed apple green birefringence under polarized light. The liver biopsy showed partial disruption of the liver architecture with variable degree of deposition of amyloid in the sinuses and few portal vessels causing focal compression of the liver cell plates [Figure 6]. There was mild acute and chronic inflammation in portal areas. Congo red staining confirmed this to be amyloid. Immunohistochemical staining with Amyloid A (AA) was negative. The patient had been started on empirical ATT. She did not show any improvement, hence the ATT was stopped. The patient was investigated to exclude multiple myeloma. Her kappa, lambda-free light chains were within normal limits. She was put on supportive and symptomatic treatment. However, she succumbed to the disease within 2 months.

- Congo red staining shows linear deposits of amyloid on abdominal fat pad aspiration(×400)

- Liver biopsy showing amyloid deposition (H and E, ×400)

It is imperative to further classify amyloid as localized or systemic and primary, secondary, hereditary, or other rare types. Immunohistochemical panel comprising kappa and lambda light chains, antisera to AA, and anti-transthyretin can help recognize most forms of amyloid. In cases where immunohistochemistry is noncontributory, amino acid sequencing or ultrastructural examination is the definite method to characterize amyloid protein.[2]

In the present case, lymph node involvement was a part of systemic amyloidosis. The material in cell block was insufficient for immunohistochemistry. Immunostaining with AA done on liver biopsy was negative. The kappa- and lambda-free light chains and kappa/lambda ratio were also within normal limits. The exact chemical nature of amyloid protein could not be ascertained in this case.

The clinical symptoms of amyloidosis are variable and nonspecific and depend on the type and extent of organs involved. The radiologic features are also nonspecific. Calcifications, as observed radiologically in the present case, are not an infrequent feature.[11] The diagnosis of this entity is almost always confirmed by biopsy of the affected organ.

In deep-seated lymph nodes, the diagnosis of amyloidosis is usually made after surgery or by invasive biopsy techniques.[12] Krishna et al. recently described a case of pancreatic amyloidosis diagnosed on EUS-FNA. They emphasized on the potential role of EUS for procuring samples from extraluminal accessible sites for cytologic diagnosis of amyloidosis.[13] The present case is interesting because the diagnosis was initially clinched by EUS-guided FNA of abdominal lymph nodes. With the advent of newer imaging modalities, the cytopathologists will have a pivotal role in diagnosing a broader spectrum of entities than ever before.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

AG, GK, AK, SJ, and VG have made substantial contribution to conception, design, and data acquisition. AG, GK, AK, VG, PB, KV, AA, and SJ participated in drafting the article and revising it critically.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is a quiz case without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from Institutional Review Board (or its equivalent).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

AA - Amyloid A

ATT - Anti-Tubercular Therapy

EUS-FNA - Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration

FNAC - FNA Cytology

ZN - Ziehl–Neelsen

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Amyloid in cytologic specimens. Differential diagnosis and diagnostic pitfalls. Acta Cytol. 1999;43:746-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- The classification and typing of amyloid deposits. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:787-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration cytology of amyloid associated with nonneoplastic and malignant lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 1998;18:270-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urine cytology of localized primary amyloidosis of the ureter: A case report. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:319-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytodiagnosis of hepatic amyloidosis by fine needle aspiration cytology: A case report. Acta Cytol. 2006;50:574-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plasmacytoma with amyloidosis masquerding as tuberculosis on cytology. J Cytol. 2009;26:161-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of mediastinal lymph nodes: Experience from region with high prevalence of tuberculosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:1019-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymph nodes and spleen. In: Wick MR, LiVolsi VA, Pfeifer JD, Stelow EB, Wakely PE, eds. Silverberg's Principles and Practice of Surgical Pathology and Cytopathology. England: Cambridge University Press; 2015. p. :688-812.

- [Google Scholar]

- Massive cervical and abdominal lymphadenopathy caused by localized amyloidosis. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:343-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of amyloid in abdominal fat pad aspirates in early amyloidosis: Role of electron microscopy and Congo red stained cell block sections. Cytojournal. 2011;8:11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary amyloidosis involving mediastinal lymph nodes diagnosed by EBUS TBNA. Respir Med CME. 2009;2:51-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- A first report of endoscopic ultrasound for the diagnosis of pancreatic amyloid deposition in immunoglobulin light chain (AL) amyloidosis (primary amyloidosis) JOP. 2013;14:283-5.

- [Google Scholar]