Translate this page into:

Cytopathological yarn of a suprasellar mass lesion: Diagnostic clues and pitfalls

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

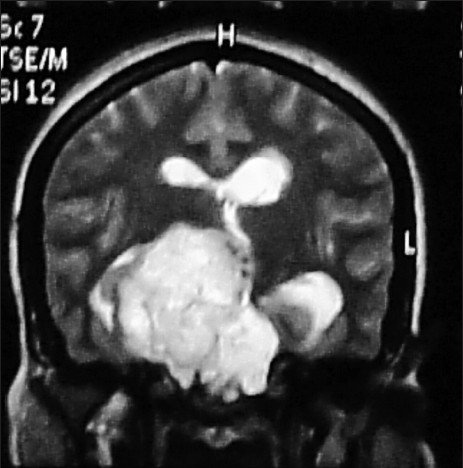

A 35-year-old female presented with left-sided hemiparesis of 3 months duration, followed by left-sided unilateral headache. On physical examination, power was reduced in left-sided extremities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large lobulated heterogeneously enhancing extra-axial lesion in sellar, parasellar, and suprasellar regions with erosion of bony sellar and clivus with extension. Figure 1a–d shows the cytomorphological features of the squash smear of the lesion.

![Squash smear cytology of sellar lesion. (a) Cellular smear showing tumor cells in clusters and singles against a metachromatic fibrillary mxyoid background (MGG, ×200). (b) Tumor cells are large round to oval cells having distinct cell borders, moderate to abundant cytoplasm, and mildly pleomorphic vesicular nucleus. Individual tumor cells are surrounded by fibrillary matrix (red arrow). Some of the tumor cells show vacuolated cytoplasm (Inset [zoomed] with yellow arrow) (MGG, ×400). (c) Tumor cells show binucleation and noticeable nucleoli (Inset (zoomed) with yellow arrow) (MGG, ×400). (d) Cellular smear showing polygonal tumor cells in clusters and sheets with myxoid material in the background. Tumor cells are polygonal/round/oval/spindle shaped. Some of the tumor cells (physaliphorous) show cytoplasmic vacuoles of varying size (Inset [zoomed] with yellow arrow) (H and E, ×200)](/content/105/2016/13/1/img/CJ-13-5-g001.png)

- Squash smear cytology of sellar lesion. (a) Cellular smear showing tumor cells in clusters and singles against a metachromatic fibrillary mxyoid background (MGG, ×200). (b) Tumor cells are large round to oval cells having distinct cell borders, moderate to abundant cytoplasm, and mildly pleomorphic vesicular nucleus. Individual tumor cells are surrounded by fibrillary matrix (red arrow). Some of the tumor cells show vacuolated cytoplasm (Inset [zoomed] with yellow arrow) (MGG, ×400). (c) Tumor cells show binucleation and noticeable nucleoli (Inset (zoomed) with yellow arrow) (MGG, ×400). (d) Cellular smear showing polygonal tumor cells in clusters and sheets with myxoid material in the background. Tumor cells are polygonal/round/oval/spindle shaped. Some of the tumor cells (physaliphorous) show cytoplasmic vacuoles of varying size (Inset [zoomed] with yellow arrow) (H and E, ×200)

QUESTION

Q1: What is your interpretation?

-

Chondrosarcoma

-

Metastatic adenocarcinoma

-

Chordoma

-

Craniopharyngioma.

ANSWER

The correct cytopathology interpretation is:

c. Chordoma.

Intraoperative squash cytological diagnosis is fairly accurate, safe, simple, and reliable tool for rapid diagnosis of central nervous system lesions and is a preferred method as it offers a great detail of cellular morphology, avoiding distortion and ice artifacts often introduced by frozen section.[12] Some authors opine that the role of cytology in preoperative diagnosis of chordoma is simple, reliable, and unquestionable.[345] On the contrary, Hernández-León et al.[6] suggest that cytological study of chordoma is not easy, due in part to differential diagnoses considered and to scarce experience with these tumors. MRI revealed features shown in Figure 2. Radiological differential diagnoses were primary neoplasm of basisphenoid bone, bone metastasis, and atypical meningioma. The patient underwent right frontal craniotomy with radical excision of the tumor. Intra-operatively, tumor was located in the suprasellar region.

- Magnetic resonance imaging showed a large lobulated heterogeneously enhancing extra-axial lesion measuring 5.8 cm × 5.3 cm × 4.3 cm in the sellar, parasellar, and suprasellar regions with erosion of bony sellar and clivus with extension

Chondrosarcomas usually demonstrate cartilaginous differentiation with abundant matrix material in the background. They do not contain physaliphorous cells and help in differentiating it from chordoma. Metastatic adenocarcinoma shows mucinous cytoplasmic vacuoles which are less numerous than physaliphorous cells and the nuclear pleomorphism and irregularities being more common. Cytoplasmic vacuoles of metastatic renal cell carcinoma are small, fine, and mucin negative whereas vacuoles of chordoma are bigger and mucin positive.[7]

Features favoring chordoma over other differential diagnoses are listed as follows:

-

Presence of physaliphorous cells

-

Neoplastic cells showing cytoplasmic vacuoles of varying sizes

-

Distinct cell border

-

Mildly pleomorphic or relatively bland nucleus with noticeable nucleoli

-

Fibrillary myxoid background

-

Individual cells surrounded by fibrillary material.

In hematoxylin and eosin-stained smears, tumor cells appeared polygonal closely mimicking squamous cells of craniopharyngioma. The extracellular material at places simulated wet keratin. Characteristic physaliphorous cells were sparse. Considering the site of the lesion in sellar-suprasellar region and deceptively bland-looking nuclear morphology, a diagnosis of adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma was considered. However, in view of the background myxoid material noted in May–Grünwald–Giemsa-stained smears, possibility of chordoma was also suggested. Background gave us a clue to the possible correct diagnosis. We attribute this to morphologic mimicry, diagnostic dilemma, and rarity.

ADDITIONAL QUIZ QUESTIONS

Q2: Which of the following is a hallmark feature of chordoma?

-

Myxoid background

-

Physaliphorous cells

-

Binucleated cells

-

Nuclear pleomorphism.

Q3: Which of the following favor chordoma over metastatic adenocarcinoma?

-

Fibrillary background

-

Bland nuclear morphology

-

Abundant clear bubbly cytoplasm

-

All the above.

Q4: Which of the following is a relatively specific immunohistochemistry (IHC) marker for chordoma?

-

Brachyury

-

S-100

-

Epithelial membrane antigen (EMA)

-

Low molecular weight cytokeratins.

ANSWERS TO ADDITIONAL QUESTIONS

Q2 (b); Q3 (d); Q4 (a).

Q2 (b): [Figure 1b and c] Physaliphorous cells are large, round cells with 1-2 small round nuclei, fine chromatin, small nucleoli, and clear bubbly cytoplasm.[8] The presence of physaliphorous cells is considered as a defining feature for the diagnosis of chordoma.[5] However, chordoma has been described even in the absence of physaliphorous cells.[9] Physaliphorous (drop-bearing) cells may be vacuolated in classical variant and eosinophilic and atypical in the chondroid variant.[2] In the smear, classical physaliphorous cells were very few. It is suggested that the physical force of a smear destroys the largest, most flagrant and fragile of the physaliphorous cells.[10] The nucleus of physaliphorous cells was not intented by cytoplasmic vacuoles. Crapanzano et al.[11] observed nuclear indentation in only four cases (33.33%) in their study.

Myxoid background may be seen even in myxoid chondrosarcoma and mucinous adenocarcinoma.[2] Binucleated and multinucleated cells can be seen in both chondrosarcoma and chordoma. Nuclear pleomorphism and irregularities are found even in well-differentiated adenocarcinoma.[7]

Q3 (d): Fibrillary background with fibrillary matrix encasing the individual tumor cells favor chordoma.[8] Cords and islands of tumor cells may be suspended in mesenchymal mucus.[12] The nuclei of most chordoma display a monotony and blandness that belies the seriousness of this tumor. Pleomorphism, hyperchromasia, and anaplasia may be minimal in chordoma.[10] Clear mucinous vacuoles in adenocarcinomas are generally less numerous. Cytoplasmic bubbles favor physaliphorous cells of chordoma.[7]

Q4 (a): Chordoma was originally described as one of the unique “triple positive” (EMA/S-100 protein/keratins) neoplasia in bone and soft tissue Pathology. EMA is positive in chordoma and negative in chondrosarcoma and chordoid meningioma.[13] However, these have not been useful for differential diagnosis since adenocarcinomas show similar pattern of staining.[7] However, Kanthan and Senger[5] are of the opinion that immunocytochemical stains may be a useful adjunct in distinguishing chordomas from other lesions. Additional markers such as vimentin, cathepsin K, and E-cadherin have been included in the panel.[614]

Brachyury is a transcription factor which is required for posterior mesodermformation and differentiation as well as for notochord development during embryogenesis. According to recent evidence, brachyury represents a unique specific diagnostic marker for chordoma, helpful to differentiate this tumor from all of its mimickers.[13] In a study conducted by Jambhekar et al.,[15] brachyury expression was observed in 90.2% cases with 100% specificity. The expression of brachyury has been also documented in the stromal cells of hemangioblastoma.[13]

BRIEF REVIEW OF THE TOPIC

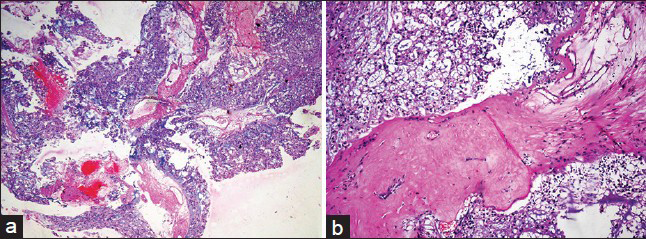

The patient underwent right frontal craniotomy with radical excision of the tumor. Specimen sent for histopathology showed multiple friable gray to bluish white gelatinous, fragments altogether measuring 1.5 cm × 1 cm. Sections showed a tumor composed of cells arranged in sheets, cords, and lobules, separated by fibrous septae [Figure 3a]. Tumor cells had abundant vacuolated bubbly cytoplasm (physaliphorous cells) [Figure 3b]. Tumor cells showed mild nuclear atypia. Also seen were abundant fibromyxoid areas and foci of necrosis. Final diagnosis of chordoma was made. Postoperative period was uneventful.

- Histology of sellar lesion. (a) Low power view of lobulated tumor tissue with areas of hemorrhage (H and E, ×100). (b) Tumor tissue showing physaliphorous cells in lobules separated by fibrous septa (H and E, ×200)

We have to consider and correlate clinical parameters such as age, sex, clinical presentation, and radiological features with cytological features while assessing the squash smear.

Potential pitfalls in cytological diagnosis of chordoma:

-

Presence of only few physaliphorous cells due to destruction of cells by physical force

-

Deceptively bland nuclear morphology with minimal pleomorphism or nuclear irregularity

-

Cytomorphological mimickers of the lesion.

Chordoma is a rare, slow growing, locally aggressive, and uncommonly metastazing neoplasm with high rate of recurrence.[5] It is a rare bone tumor accounting for 1–4% of all primary malignant bone tumors. It is a low to intermediate grade malignant tumor that recapitulates notochord. The tumors are common in the sixth decade with male:female ratio of 1.8:1. They are most commonly located in sacrum (60%). Other sites of involvement of chordoma are spheno-occipital/nasal (25%), cervical (10%), and thoracic (5%) regions. Those lesions located in spheno-occipital region are often associated with chronic headache and symptoms related to cranial nerve compression.[16] Chordoma was originally described by Virchow in 1857. It was named physaliphorous enchondrosis for its resemblance to chondroid tumors. In 1894, Ribbert assigned a notochordal origin for this neoplasm by comparison with pulpous nuclei of intervertebral discs.[6] Long-term prognosis of chordoma is poor, despite their low tendency to metastasize. The metastatic rates are as high as 26–43%, common sites being liver.[5]

Clinical significance of recognizing the lesion:

-

Chordoma needs adjuvant radiotherapy

-

Low-grade chondrosarcoma is managed by conservative surgery

-

Metastatic adenocarcinoma may require adjuvant chemotherapy.

FOCUSED DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF CHORDOMA

Myxoid chondrosarcoma

Pattern: Cellular smear composed of tumor cells in cords.[8]

Cells: Uniform large, round to oval cells.

Nuclear features: Mononucleated/binucleated cells in lacunae, nuclear grooves, and intracytoplasmic nuclear invaginations.[817]

Background: Abundant metachromatic myxoid stroma.[8]

IHC: Express S-100 protein.[8]

Metastatic adenocarcinoma

Depends on the nature of primary tumor.[17]

Pattern: Aggregates, cell balls, papillary pattern, and singles.

Cells: Rounded cells, malignant signet ring cells.[11]

Cytoplasm: Clear to foamy cytoplasm, cytoplasmic mucin vacuoles displace and distort nucleus.

Nucleus: Single eccentric nucleus, and at times a low N/C ratio, hyperchromatic nuclei vary from bland to obviously malignant; contours may be sharply angulated or pointed and variable nucleoli.

Background: Abundant pools or strands of mucin.[8]

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma

Pattern: Scantily cellular smears with tumor cells in sheets, clusters, or singles.[8]

Cells: Clear cells, may contain different cell types.[817]

Nuclear features: Exhibit variable degrees of nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic activity.

Cytoplasm: Clear cells with abundant, fragile, and vacuolated cytoplasm, with or without granular cells with a moderately dense and granular eosinophilic cytoplasm.[8]

Background: Hemorrhagic.[17]

IHC: Positive for EMA, vimentin, and CD10, and infrequently positive for CK-7.[8]

Chordoid meningioma

Cellularity: Moderate.[18]

Pattern: Cords, nests, and whorls.[218]

Cells: Spindle or epithelioid cells.

Nuclear features: Round nuclei, stippled chromatin, intranuclear inclusions.[18]

Cytoplasm: Eosinophilic vacuolated cells.[2]

Background: Myxoid matrix, necrotic.[18]

Myxopapillary ependymoma

Pattern: Papillary, fern, and rosette pattern with perivascular radiating tumor cells, spheres of myxoid material encased by tumors cells.[101920]

Cells: Cuboidal to columnar cells, epithelial, and glial properties.[1020]

Nuclear features: Bland and monotonous nuclei.[10]

Cytoplasm: Well-defined borders (epithelioid) or fibrillary processes (glial).[20]

Background: Myxoid lakes.[10]

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All the authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as define by ICMJE http://icmje.org/#author

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is a quiz case without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) (or its equivalent).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

EMA - Epithelial Membrane Antigen

IHC - Immunohistochemistry

IRB - Institutional Review Board

MRI - Magnetic Resonance Imaging

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We sincerely acknowledge the Department of Radiology, JSSMC, Mysore, and Department of Neurosurgery, JSSMC, Mysore, for the kind cooperation extended to us toward working up the case.

REFERENCES

- Role of squash smear technique in intraoperative diagnosis of CNS tumors. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2013;2:889-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Presacral chordoma diagnosed by transrectal fine-needle aspiration cytology. J Cytol. 2011;28:89-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration cytology with histological correlation of chordoma metastatic to the lung: A diagnostic dilemma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:927-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of primary or recurrent chordomas. Cytopathology. 2011;22:340-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case of sacrococcygeal chordoma diagnosed by fine needle aspiration biopsy cytology. Korean J Pathol. 1988;22:356-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytology of soft tissue, bone and skin. In: Bibbo M, Wilbur DC, eds. Comprehensive Cytopathology (3rd ed). China: Elsevier; 2008. p. :471-513.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic diagnosis of a chordoma without physaliferous cells: A case report. Korean J Cytopathol. 2001;12:131-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Regional tumors. In: Joseph JT, Pine J, McGough J, Dougherty B, Rivera B, Panetta A, eds. Diagnostic Neuropathology Smears (1st ed). Massachusetts: Walsworth Publishing Co; 2007. p. :1-234.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chordoma: A cytologic study with histologic and radiologic correlation. Cancer. 2001;93:40-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant neoplasms of the neck (soft tissue, bone, and lymph node) In: Thomson LD, Goldblum JR, eds. Head and Neck Pathology. China: Elsevier; 2013. p. :479-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Brachyury: A diagnostic marker for the differential diagnosis of chordoma and hemangioblastoma versus neoplastic histological mimickers. Dis Markers 2014 2014:514753.

- [Google Scholar]

- Axial chordoma and parachordoma (soft tissue chordoma): Two of a kind: Report of two cases with primary diagnosis on fine-needle cytology samples. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:475-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Revisiting chordoma with brachyury, a “new age” marker: Analysis of a validation study on 51 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1181-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2002. p. :316-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benign and malignant tumors of bone. In: Gray W, Mckee GT, eds. Diagnostic Cytopathology (2nd ed). China: Elsevier; 2003. p. :917-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytology of chordoid meningioma: A series of five cases with emphasis on differential diagnoses. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1024-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The central nervous system. In: Koss LG, Melamed MR, eds. Koss's Diagnostic Cytology and its Histopathologic Bases (5th ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. p. :1523-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytomorphologic features of myxopapillary ependymoma: A review of 13 cases. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:297-302.

- [Google Scholar]