Translate this page into:

Impact of immediate evaluation of touch imprint cytology from computed tomography guided core needle biopsies of mass lesions: Single institution experience

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Computed tomography (CT) guided core needle biopsy (CT-guided CNB) is a minimally invasive, safe and effective manner of tissue sampling in many organs. The aim of our study is to determine the impact of on-site evaluation of touch imprint cytology (TIC) to minimize the number of passes required to obtain adequate tissue for diagnosis.

Design:

A retrospective review of all CT-guided CNBs performed during 4 year period, where pathologists were present for on-site TIC evaluation. Each case was evaluated for the number of passes required before TIC was interpreted as adequate for diagnosis.

Results:

A total of 140 CT-guided CNBs were included in the study (liver, lung, kidney, sacral, paraspinal, omental, splenic and adrenal masses). Of the 140 cases, 109 were diagnosed as malignant, 28 as benign and three insufficient. In 106 cases (75.7%), the biopsies were determined adequate by TIC on the first pass, 19 cases (13%) on the second pass and 7 cases (5%) on the third pass. Only in 5 cases (3.6%), more than three passes were required before diagnostic material was obtained. Three cases (2.14%) were interpreted as inadequate both on TIC and on the final diagnosis. Of the biopsies deemed adequate on the first pass, 71% resulted in either termination of the procedure, or only one additional pass was obtained. In five cases, based on the TIC evaluation, a portion of the sample was sent for either flow cytometric analysis or cytogenetic studies.

Conclusions:

In the majority of cases, adequate material was obtained in the first pass of CT-guided CNB and once this was obtained, either no additional passes, or one additional pass was performed. This study demonstrates the utility of on-site evaluation in minimizing the number of passes required for obtaining adequate diagnostic material and for proper specimen triage for ancillary studies, which in turn decreases the risk to the patient and costs. However, tumor exhaustion in the tissue as a result of TIC is an important pitfall of the procedure, which occurred in 9 (8.2%) of our malignant cases.

Keywords

Biopsy

core

touch imprint

INTRODUCTION

Core needle biopsy (CNB) has been adopted as a minimally invasive and effective method of tissue sampling of many organs. CNB provides an equal or greater sensitivity and specificity then fine-needle aspiration (FNAs) biopsies and is a less invasive procedure when compared with open surgical biopsies.[12] When compared with FNA, CNB provides more sample material for evaluation and more often leads to a definitive diagnosis.[1] In our experience, CNB has become the diagnostic procedure of choice in many visceral organ samplings. The method of obtaining tissue through CNB involves either ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) to guide the 18-gauge needle.[3] With each pass of the needle through the suspected lesion, small amounts of specimen are collected. To ensure adequate specimen is obtained for analysis, often times multiple passes of the needle are required to collect the sample.

The implementation of touch imprint cytology (TIC) as a method of evaluating sample collected through ultrasound guided or CT-guided CNB has improved the efficacy and expedited results.[4567] TIC in CNB specimens enables immediate reporting on specimen amount and composition without any additional risk to the patient.[278] TIC procedure involves gently pressing the specimen obtained through CNB onto a glass slide, fixing the cells on the slide and examining them under the microscope. This method is useful in establishing morphology of cells quickly, typically requiring 1-2 min before a preliminary diagnosis is made[9] while preserving the original sample for further histopathologic analysis.[7] In this manner, an on-site pathologist is able to determine not only if the core biopsy needle has been placed in to correct position to obtain the lesion in question, but also whether adequate amount of sample is collected.

In the present study, we examined whether on-site evaluation of TIC in CT-guided CNBs minimized the number of passes required to obtain adequate diagnostic tissue and its impact on specimen triaging. Our study took into account CT-guided CNBs performed in our institution, where a pathologist was present for on-site evaluation of TIC from various sites. Each case was evaluated for: (1) The number of passes required before the TIC was interpreted as adequate, (2) the total number of passes performed and (3) the number of cases where on-site evaluation assisted in triaging specimen for appropriate ancillary studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples

Computer-assisted search of CT-guided CNB procedures at the University of Louisville during a 4 year period yielded 140 CNBs, which were retrospectively analyzed for this study. The CNBs were performed on patients with mass lesions in various locations, including the liver, lung, kidney, sacrum, omentum, spleen, adrenal gland, bone, muscle and para-spinal soft-tissue.

Specimen collection, processing and evaluation

The patients received local anesthesia for comfort prior to the procedure and the CNBs were obtained by an interventional radiologist using CT or ultra sound-guided technique. As soon as the core biopsy was obtained, it was carefully touched on the slide and then gently lifted with forceps, leaving a touch imprint of the specimen on the slide. The slide was then air dried, immersed in 95% ethanol for 5 s, eosin for 15 s and diff-quick solution for 15 s before microscopic evaluation. The core biopsy specimen was placed in 10% buffered formalin for further fixation and staining. Once the diagnostic material was visualized through touch imprint, the subsequent needle cores were directly placed in formalin for fixation. All of the collected touch imprint specimens and hematoxylin and eosin stained tissue core sections were examined by a board certified general pathologist or a cytopathologist. A single on-site pathologist analyzed the collected specimens and the cytological observations were then grouped into two diagnostic categories; inadequate and adequate (to include benign, suspicious and malignant diagnostic categories). Specimen was deemed adequate when smears contained sufficient number of cells of a specific organ, with cytomorphic features consistent with, or supportive of, the clinical or radiologic diagnosis.[10]

If the sample was deemed “inadequate,” a repeated pass was performed by the interventional radiologist on site. The new sample was then analyzed in the same manner, until the sample was classified as “adequate” or the procedure was terminated due to outlying factors such as radiologist's access to the tissue site, patient's discomfort, or increase in risk of the procedure and morbidity.

When lymphoma was suspected during immediate evaluation of touch imprints, an additional core was requested to be placed directly in RPMI for flow cytometry or cytogenetic analysis.

RESULTS

Out of 140 total CNBs performed with TIC and immediate on-site evaluation, 109 (77.9%) cases were diagnosed as malignant and 28 (20%) as benign. In 10 out of 28 cases granulomas were identified on TIC and on the core biopsies. Eight cases had benign changes consistent treatment effect with no residual tumor. Nine cases showed inflammatory process including fat necrosis and mesothelial proliferation and one case was hematoma.

Three cases produced insufficient material from the CNBs and were deemed “Inadequate” both on TIC evaluation and on the final diagnosis.

Eight cases (6%) were interpreted as benign on TIC and malignant on CNB. The TIC were reviewed and the interpretation was confirmed. The causes of this discrepancy were contributed to “sampling errors.” In 9 (8.2%) of the malignant cases the tumor cells were present only on TIC slides and the cores were depleted of the malignant cells. These samples were obtained from liver and lung. These cases deemed adequate based on the cytologic features on the touch imprint. In three cases diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma and in six cases diagnosis of adenocarcinomas were favored based on the cytological features of the malignant cells obtained on the touch imprint slides. Additional confirmation was reached through immunostaining of the destained touch imprint slides. Three cases of the liver were metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma and the diagnoses were confirmed with assessment of the cytological features of the touch imprint slides and comparison with the original tumor.

Follow-up was available for 27 positive cases. No false positive result was noted. As for the benign lesions histological follow-up were not available however reviewing the charts revealed clinical follow-up in 15 patients and no diagnosis of malignancy was documented.

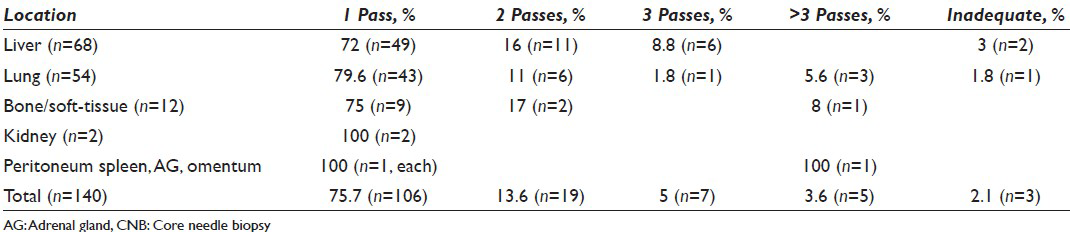

Of the 137 adequate biopsies, 106 (75.7%) were deemed adequate by TIC on the first pass and in 19 cases (13.6%), adequacy was reached with an additional pass. Seven cases (5%) required a third pass to be performed. Only five of the 140 cases (3.6%) required more than three passes to be performed before an adequate sample was collected and these samples were collected from the lung (3 of 5 or 60%), peritoneum (1 of 5 or 20%) and bone/soft-tissue (1 of 5 or 20%). Table 1 summarizes our findings.

Of the biopsies that were adequate on the first pass, 71% resulted in termination of the procedure or one additional pass to be performed. In five cases, the prompt on-site TIC examination resulted in a portion of the fresh sample to be sent for ancillary studies, including flow cytometry and cytogenetic studies.

Of the 140 cases evaluated at our institution, adequate tissue was obtained with the use of TIC in 75.7% of cases with just the first pass sample, greatly eliminating the need for additional biopsies in 71% of samples. The liver and lungs were the most common sites of biopsy seen in our study of 140 cases, with 68 of the cases (49%) involving the liver and 54 (39%) the lungs. These tissue sites are oftentimes difficult to biopsy, with a great potential for adverse events such as bleeding, pneumothorax with multiple repeated attempts.[811121314] In our study, 72% of liver biopsies were discontinued after evaluation of a single pass, relieving the patient from unnecessary risk of bleeding which can be caused by repeated attempts. Furthermore, 79.6% of lung biopsies evaluated by onsite TIC, resulted in termination after a single pass. Of the 140 cases evaluated, three cases (2.1%) were terminated before adequate tissue was collected and in these cases the liver and lung were the collection sites.

The size of the lesions was available for 65 cases and it ranged between 0.7 cm and 12 cm. No statistically significant relationship was noted between the size of the lesion and the success of the procedure.

As per radiology reports, complications related to the procedure was only small Pneumothorax in 18 cases (33%). One case of subcapsular hematoma was reported after a liver biopsy. No complication required further work-up.

Our data did not show any relation between the number of the passes and the rate of complication. Our data demonstrates that the use of TIC by on-site pathologist provided an efficient means of assessing sample adequacy while minimizing patient exposure to repeated biopsies and decreasing patient morbidity.

DISCUSSION

TIC is extremely helpful when evaluating malignancies and has been extensively used in evaluation of sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer, with studies demonstrating that TIC and frozen section histological diagnosis were comparable for detecting metastasis in the sentinel lymph nodes.[7] The use of TIC as an adjunct to CNB, not only improves the accuracy of diagnosis[61115] but decreases patient exposure to unnecessary further intervention and discomfort.[711121314151617] Whereas tissue fixation, sectioning and further evaluation may take 24-48 h,[9] TIC would provide the physician with a preliminary diagnosis in mere 1-2 min, enabling for a more rapid initiation of ancillary testing.

While it has been stated that CT-guided core needle biopsies on average could require 3-7 passes to ensure adequate sampling of the tissue,[9] undergoing less passes could reduce the risk of trauma, hemorrhage and potential for infection.[1213] An on-site evaluation of TIC by a pathologist is useful in assessing if adequate sample has been retrieved with each pass of the CNB needle, eliminating the need for unnecessary passes to be performed.

On the other hand, tumor exhaustion in the tissue as a result of TIC is an important pitfall of the procedure and can be further prevented by a gentle touch of the core biopsy. After confirmation that the right lesion has been sampled, any additional biopsy can be preserved for the permanent evaluation. This can also reduce chances of losing the material. Another problem with TIC arises with sampling of the soft-tissue tumors or recurrent tumors after radiation with extensive fibrotic background. In these cases TIC may not be helpful due to technically inferior material.

During CT-guided CNB, pathologists can direct radiologists in targeting the right lesion, efficiently triaging the specimen for histology and ancillary studies and alleviating patients discomfort by minimizing the number of needle passes. In addition, this approach also decreases the expenses associated with these procedures.[37]

Multiple studies have reported on the high accuracy of TIC as method for diagnosis of suspicious lesions.[29151819] In fact, some of these studies have shown an even greater improvement in diagnostic accuracy when TIC is combined with histopathologic studies indicating that the synergy of two methods yield better results than histopathology alone.[71519202122] Mannweiler et al. addressed multiple reasons for the increased sensitivity seen with the use of TIC such as the increase of surface area, the common problem of cutting and embedding biopsy cylinders, the amount of tissue “wasted” with sectioning of paraffin blocks and the possibility of aspiration effect during the core biopsy. With the use of on-site pathologist, one can attribute a further increase in the accuracy of TIC to improved positioning of the biopsy needle by the interventional radiologist.[11]

The use of TIC in CNB evaluation has potential to be helpful in a number of ways: For physicians, it can help in completing the procedure efficiently while getting the adequate sample that assists diagnosing the lesions with increased accuracy. For patients, TIC can be beneficial in minimizing procedure related complications and discomfort, providing a quick preliminary diagnosis and alleviating uncertainties and avoiding unnecessary costs associated with repeated procedures.

In our study, minimal complications associated with CNBs included small pneumothorax and hemorrhage in which are comparable to the previous study performed by Loh et al.[14]

Our study demonstrates that the use of TIC by an on-site pathologist was an effective and efficient method of obtaining adequate diagnostic material, while expediting ancillary studies and decreasing the risk and potential cost associated with the procedure.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by the ICJME. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of the article.

MP and AF are responsible for execution and analysis of the work and drafting the manuscript.

HA and MM are responsible for planning and revising the article and responsible for conceiving and coordinating the whole work, execution and analysis of the work and final approval of the version to be published.

Each author acknowledges that the final version was read and approved.

All authors take the responsibility of maintaining relevant documentation of records, slides and other data used in this study on archival material as per the Institutional policy. All patient identifiers were suppressed in the final analysis of the data.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors take the responsibility of maintaining relevant documentation of records, slides and other data used in this study on archival material as per the Institutional policy. All patient identifiers were suppressed in the final analysis of the data.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model.(authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Increase of core biopsies in visceral organs – Experience at one institution. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:791-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Touch imprint cytology of core needle biopsy specimens: A useful method for immediate reporting of symptomatic breast lesions. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:490-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytopathologic touch preparations (imprints) from core needle biopsies: Accuracy compared with that of fine-needle aspirates. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:1277-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intraoperative imprint evaluation of surgical margins in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Cytol. 2013;57:75-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accuracy of touch imprint cytology of image-directed breast core needle biopsies. Acta Cytol. 1999;43:169-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Utility of immediate cytologic diagnosis of lung masses using ultrafast Papanicolaou stain. Lung Cancer. 2011;72:172-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Touch imprint cytology and frozen-section analysis for intraoperative evaluation of sentinel nodes in early breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:3523-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- CT-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy for small (≤20 mm) pulmonary lesions. Clin Radiol. 2013;68:e43-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic value of imprint cytology during image-guided core biopsy in improving breast health care. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2011;41:8-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- The value of immediate cytologic evaluation for needle aspiration lung biopsy. Invest Radiol. 1997;32:453-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The interventional radiologist's perspective on lung biopsy. Acta Cytol. 2012;56:636-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Image-guided percutaneous transthoracic biopsy in lung cancer – Emphasis on CT-guided technique. J Infect Public Health. 2012;5(Suppl 1):S22-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- CT-guided percutaneous biopsy of intrathoracic lesions. Korean J Radiol. 2012;13:210-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- CT-guided thoracic biopsy: Evaluating diagnostic yield and complications. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2013;42:285-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic efficacy of CT-guided transthoracic needle biopsy and fine needle aspiration in cases of pulmonary infectious disease. Jpn J Radiol. 2012;30:589-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Imprint cytology improves accuracy of computed tomography-guided percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:54-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role and accuracy of rapid on-site evaluation of CT-guided fine needle aspiration cytology of lung nodules. Cytopathology. 2011;22:306-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic yield of touch imprint cytology of prostate core needle biopsies. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:97-101.

- [Google Scholar]

- The value of touch imprint cytology in EUS-guided Trucut biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:44-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of fine needle aspiration cytology and needle core biopsy in the diagnosis of radiologically detected abdominal lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:93-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The results of frozen section, touch preparation, and cytological smear are comparable for intraoperative examination of sentinel lymph nodes: A study in 133 breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:173-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparing touch imprint cytology, frozen section analysis, and cytokeratin immunostaining for intraoperative evaluation of axillary sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55:183-6.

- [Google Scholar]