Translate this page into:

Performance of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration in diagnosing pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are rare tumors of the pancreas, which are increasingly diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA). In this retrospective study, we assessed the performance of EUS-FNA in diagnosing PNETs.

Materials and Methods:

We identified 48 cases of surgically resected PNETs in which pre-operative EUS-FNA was performed. The clinical features, cytological diagnoses, and surgical follow-up were retrospectively reviewed. The diagnostic performance of EUS-FNA was analyzed as compared to the diagnosis in the follow-up. The cases with discrepancies between cytological diagnosis and surgical follow-up were analyzed and diagnostic pitfalls in discrepant cases were discussed.

Results:

The patients were 20 male and 28 female with ages ranging from 15 years to 81 years (mean 57 years). The tumors were solid and cystic in 41 and 7 cases, respectively, with sizes ranging from 0.5 cm to 11 cm (mean 2.7 cm). Based on cytomorphologic features and adjunct immunocytochemistry results, when performed, 38 patients (79%) were diagnosed with PNET, while a diagnosis of suspicious for PNET or a diagnosis of neoplasm with differential diagnosis including PNET was rendered in the 3 patients (6%). One case was diagnosed as mucinous cystic neoplasm (2%). The remaining 6 patients (13%) had non-diagnostic, negative or atypical diagnosis.

Conclusions:

Our data demonstrated that EUS-FNA has a relatively high sensitivity for diagnosing PNETs. Lack of additional materials for immunocytochemical studies could lead to a less definite diagnosis. Non-diagnostic or false negative FNA diagnosis can be seen in a limited number of cases, especially in those small sized tumors.

Keywords

Cytomorphology

fine needle aspiration

immunocytochemistry

neuroendocrine tumor

pancreas

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are rare tumors of the pancreas that account for less than 2% of all pancreatic tumors.[12] PNETs can be sporadic or associated with genetic syndromes including the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, von Hippel-Lindau disease, von Recklinghausen disease, and tuberous sclerosis. They are typically seen in middle-age adults and are divided into functional and non-functional tumors. Functional tumors are hormonally active and are often detected secondary to the clinical syndromes produced by these hormones. However, a significant proportion of PNETs are non-functional and only detected due to symptoms related to mass effect or as an incidental finding on an imaging study.[34] These tumors are increasingly detected radiographically secondary to increased availability and improved sensitivity of imaging modalities.[5] Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is now accepted as an accurate and cost-effective method of detecting and staging pancreatic neoplasms due to the proximity of the pancreas to the upper gastrointestinal tract.[345] Compared with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging, this modality allows for increased detection of lesions as small as 0.2 cm in size.[56]

Increasing use of EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) has also allowed for more accurate pre-operative diagnoses of PNETs.[78] In fact, one study shows that when compared with CT-guided biopsies, EUS-FNA obtains an increased number of neoplastic cells and is less likely to procure a non-diagnostic specimen.[9] The sensitivity and specificity of EUS-FNA for the diagnosis of PNET are variable, but relatively high.[101112] The classic cytomorphologic features of PNETs are well-described in the cytology literature. However, cytomorphologic variants are well documented and immunocytochemistry may help to narrow the differential diagnosis or confirm the diagnosis.[3131415161718] Providing on-site evaluation is one of the key elements that enhances the diagnostic accuracy of this procedure by ensuring adequate sampling and appropriate specimen triage for ancillary testing.[3513] The aim of this study was to evaluate performance of EUS-FNA in diagnosing PNETs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The surgical pathology database was searched for patients who underwent resection of PNETs at our institution between January 2005 and January 2012. Of 62 cases, 48 patients had pre-operative EUS-FNA evaluation of the pancreatic lesions. The EUS-FNA was performed in the endoscopy suite by an interventional gastroenterologist with rapid on-site evaluation either by a cytopathologist or a cytotechnologist. The aspirated material was immediately transferred onto glass slides and smears were prepared, which were either air-dried or fixed in 95% alcohol. The air-dried smears were stained with Diff-Quik stain (Dade Diagnostics, West Monroe, LA), and available for rapid assessed on-site evaluation. The alcohol-fixed smears were stained with Papanicolaou stain. Part of the aspirate was saved in CytoRich Red fixative (BD Diagnostics, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and processed for a compact cell block. Sections were cut from the paraffin-embedded cell block and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Immunocytochemical studies were performed on cell block sections depending on the clinical and cytomorphologic differential diagnoses with appropriate positive and negative controls. The final diagnosis was based on cytomorphologic features and immunophenotypic findings if available. Typically, the diagnosis of PNET was rendered based on classic cytomorphologic features and/or immunocytochemical findings. The diagnosis of “suspicious for PNET” or “neoplasm with differential diagnosis including PNET” was rendered in cases wherein there was low cellularity or atypical cytomorphologic features and unavailability of immunostains. The surgical pathology diagnosis in the follow-up was reviewed and classified according to the 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of PNETs.[19]

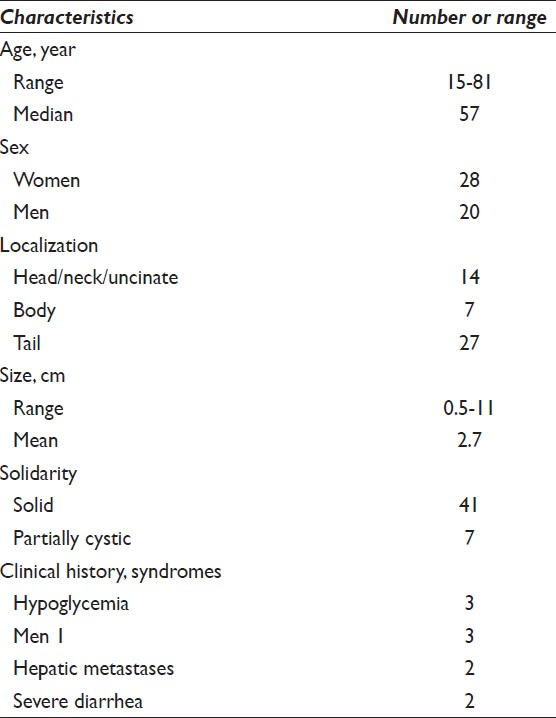

RESULTS

A total of 48 patients with PNET diagnosis in the follow-up had pre-operative EUS-FNA evaluation of pancreatic lesions during the study period. The clinical features were summarized in Table 1. A total of 28 patients were women and 20 patients were men. The mean age of the patients was 57 years old with the range from 15 to 81. In 7 patients, the lesions were discovered as a consequence of investigating clinical symptoms related to hormonal production. Two of the patients had their tumor discovered as a result of screening guidelines associated with a clinical syndrome (multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1). Fourteen of the pancreatic tumors (29%) were located in the head, neck or uncinate process. A total of 27 lesions (56%) were located in the tail of the pancreas and seven were found within the body (15%). Seven tumors (15%) appeared at least partially cystic by EUS evaluation. A total of 41 of the tumors had an entirely solid appearance (85%). The mean size of the tumors was 2.7 cm, ranging from 0.5 cm to 11 cm.

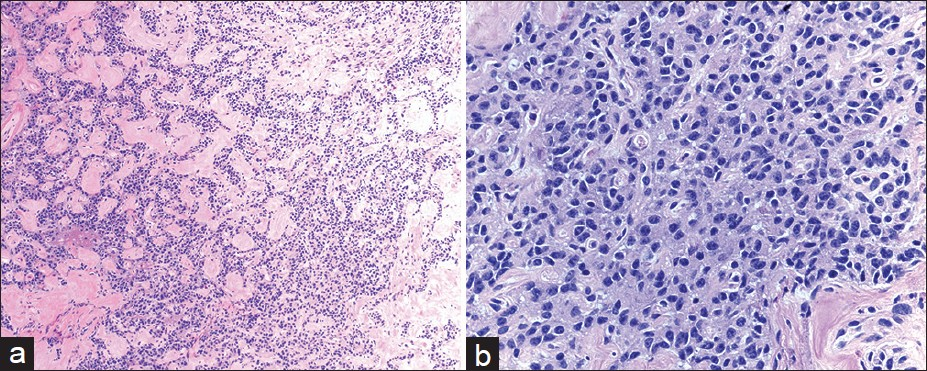

All the cases included in the current study were surgically resected tumors. Histopathologic diagnosis of PNET was reviewed and the tumors were further classified according to the current 2010 WHO clinicopathologic classification. Among them, 41 patients (85%) had Grade 1 (G1) endocrine tumors and 7 patients (15%) had Grade 2 (G2) endocrine tumors [Figure 1]. No tumors were classified as Grade 3 endocrine carcinoma in our series.

- Histomorphologic features of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm in follow-up. The resected tumor was well-circumscribed and had relatively uniform epithelial cells arranged in trabecular and gyriform growth patterns with eosinophilic stroma (a) H and E, ×100. The tumor cells have esoinophilic cytoplasma and eccentrically located round to oval nuclei with speckled chromatin (b) H and E, ×400

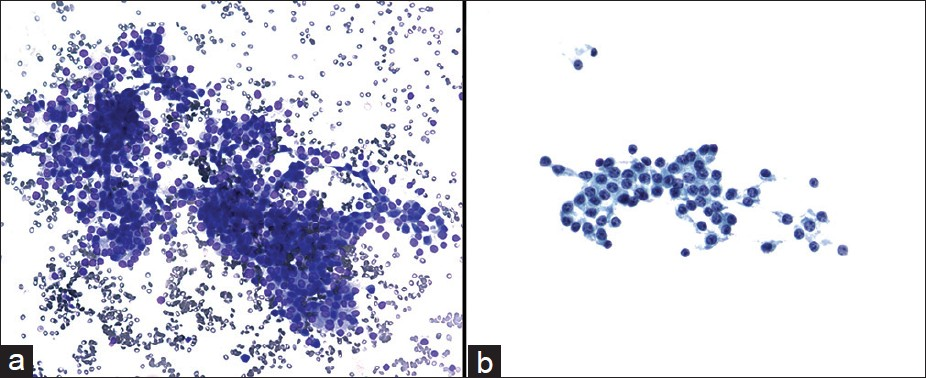

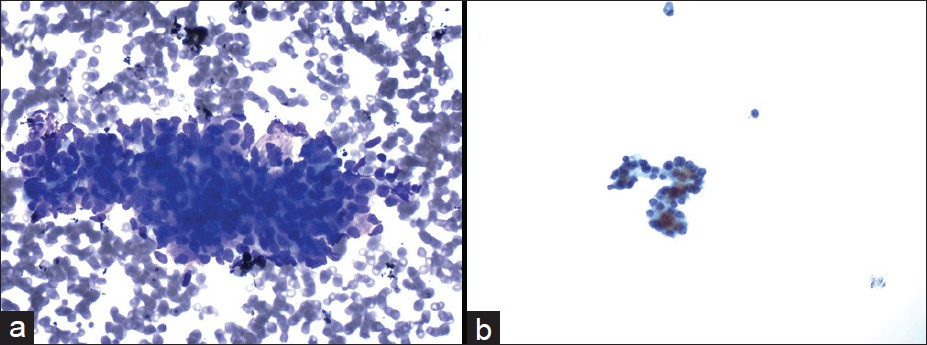

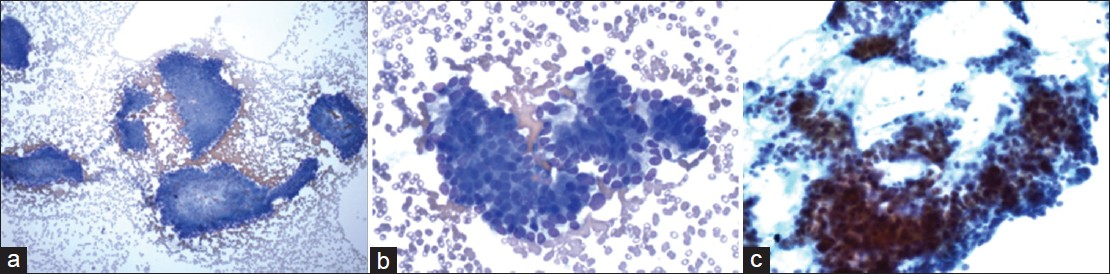

A total of 38 cases (79%) had pre-operative cytological diagnosis of PNET. In those cases, the FNA smears were often cellular. The aspirates exhibited loosely cohesive clusters of cells in a background of a pre-dominantly single cell population [Figure 2]. Some of the clusters appeared to form rosette-like structures. The cells themselves were small, monomorphic, and often had a plasmacytoid appearance. The nuclei were round to oval with smooth nuclear membranes and granular, “salt and pepper,” chromatin. The background was often blood-stained. Immunocytochemical studies were performed in 29 of 38 cases to substantiate the cytological diagnosis. All PNETs tested were positive for either synaptophysin or chromogranin [Figure 3]. CD56, another neuroendocrine marker was positive in 6 of 13 cases (46%).

- Cytmorphological features of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy. The aspirate showed loosely cohesive clusters of realtively uniform epithelial cells in a bloody background (a) Diff-Quik, ×200. The tumor cells had eccentrically located round to oval nuclei with speckled chromatin and small nucleoli (b) Papanicolaou, ×400

- Immunocytochemical featurse of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy. The cell block section showed groups of epithelial cells with eccentrically located nuclei (a) H and E, ×400. The tumor cells are positive for synaptophysin (b) immunoperoxidase stain, ×400 and chromogranin (c) immunoperoxidase, ×400

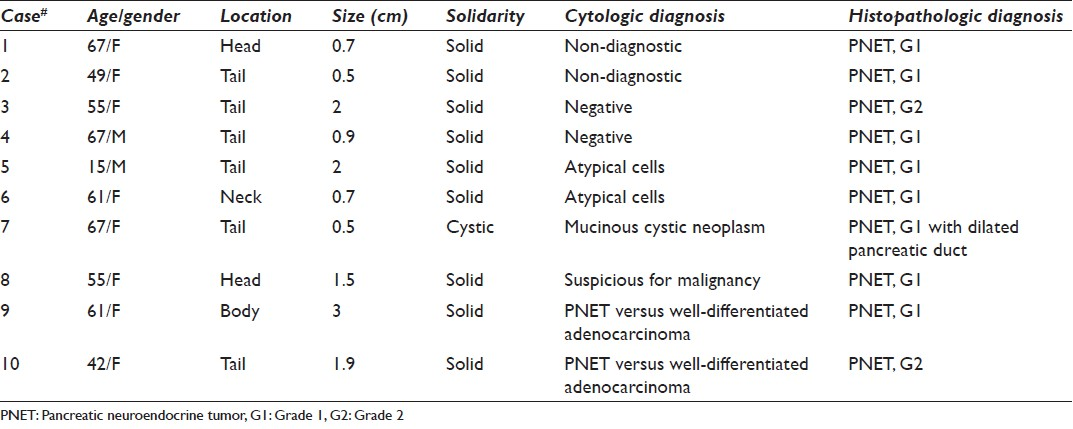

The cytological diagnoses in the remaining 10 cases were detailed in Table 2. The diagnoses included non-diagnostic (2 cases), negative (2 cases), atypical cells (2 cases) [Figure 4], mucinous cystic neoplasm (1 case), suspicious for malignancy (1 cases) or the diagnosis with differential including PNET and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (2 cases) [Figure 5]. All these cases had no additional materials available for immunocytochemical studies.

- Cytmorphological features of the case with the cytological diagnosis of atypical cells. The aspirate was paucicellular and consisted of a few group of relatively uniform epithelial cells in a bloody background ((a) Diff-Quik, ×400). The tumor cells had round nuclei and small nucleoli ((b) Papanicolaou, ×400)

- Cytmorphological features of the case with the cytological differential diagnosis including pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. The aspirate had modest cellularity ((a) Diff-Quik, ×100) and showed cohesive clusters of epithelial cells with in increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios and mild aniuncleosis ((b) Diff-Quik, ×400). The tumor cells had relapping hyperchromatic nuclei with small nucleoli ((c) Papanicolaou, ×400)

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is one of the largest series evaluating performance of EUS-FNA in diagnosing PNETs preoperatively as compared to histologic follow-up. A definite diagnosis of PNET was rendered in 38 of 48 cases (79%) based on cytomorphologic analysis with in most cases adjunct immunocytochemical studies. The majority of these tumors exhibited cellular smears on EUS-FNA. The tumor cells were present as dyscohesive groups and/or dispersed single cells and often displayed a plasmacytoid appearance. The nuclei showed smooth nuclear membranes with finely granular chromatin and low nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios. The cytological findings in our series were similar to that previously described by other groups.[14182021] When present in abundance, these features are characteristic of PNETs. However, immunocytochemical studies with neuroendocrine markers are often used to substantiate a definitive diagnosis.

Based on the cytomorphologic features, a few entities such as solid pseudopapillary tumor (SPT), acinar cell carcinoma, ductal adenocarcinoma, and plasmacytoma may sometimes be included in the differential diagnosis. The addition of immunocytochemistry may allow for the distinction between PNET and these entities. SPTs are seen most commonly in young adult women. The tumor cells are monomorphic, oval to round, and may exhibit papillary clusters. The tumor cells may stain weakly with neuroendocrine markers, but stain positively with CD10 and beta-catenin in a nuclear pattern.[222324] Acinar cell carcinoma tumor cells contain granular amphophilic to eosinophilic cytoplasm, which stain positively with antibodies against the pancreatic enzymes trypsin and chymotrypsin.[1] Ductal adenocarcinomas often have vacuolated cytoplasm and exhibit significant cytological atypia without the overall uniformity seen in PETs.[3] Furthermore, these tumors should not show strong staining for neuroendocrine markers. Plasmacytomas show dispersed single cells with prominent eccentrically located nuclei. The tumor cells will show reactivity to CD138 and lack of staining with neuroendocrine and epithelial markers.[3]

Neuroendocrine differentiation can be confirmed by immunocytochemical studies with neuroendocrine markers such as chromogranin, synaptophysin, and CD56. In the present study, synaptophysin and/or chromogranin immunostains were performed in the majority of the cases and all of the tested cases (100%) were positive. Six of thirteen cases (46%) stained positively for CD56. These results suggest that one neuroendocrine marker, either chromogranin or synaptophysin, is sufficient for elucidating neuroendocrine differentiation in PETs, at least in relatively well-differentiated tumors. Since immunocytochemical studies as an adjunct test play a pivotal role in the diagnosis of PNETs, it is crucial to save additional biopsy material for a cell block preparation during the procedure.

There were 10 cases in the current series we failed to render a definite pre-operative cytological diagnosis of PNET. The causes for the failure might be multifactorial. First, the size of tumor may play a role. Five of these ten cases had the tumor size smaller than 1 cm, which may result in an inadequate sampling and lead to absence or rarity of neoplastic cells on FNA specimens. Second, an associated lesion might complicate a correct diagnosis. There was a case in which a 0.5-cm PNET was associated with distal pancreatic duct dilatation. On the fine needle aspirates, there was a moderate amount of mucin intermixed with ductal epithelial cells. Based on the cytomorphologic features, a diagnosis of mucinous cystic neoplasm was rendered. In fact, the PNET itself was not adequately sampled. Lastly, atypical cytomorphologic features such as cohesive clusters of epithelial cells, pleomorphic cell population and conspicuous nucleoli seen in three cases appeared to hamper a cytological diagnosis. Inability to reach a definite diagnosis in these cases highlights the importance of immunocytochemistry in rendering a definite diagnosis.

According to current WHO tumor classification criteria, neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas can be further classified and graded based on the clinical and histopathologic features.[19] Although pre-operative classification/grading may help guide appropriate clinical management,[202526] precise classification of these tumors is extremely difficult, if not impossible. Most of these tumors have overlapping cytomorphologic features on EUS-FNA, which do not allow for specific classification/grading. The one exception is large cell or small cell (G3) endocrine carcinoma, which often have significant cytologic atypia. Recently, several groups have analyzed EUS-FNA material in an attempt to stratify these lesions based on cytologic material with the help of ancillary studies.[21232728] However, these findings have yet to be validated in large-scale well-controlled studies. Nevertheless, these tumors are best diagnosed as “PNET” based on the findings from EUS-FNA.

In summary, EUS-FNA can accurately diagnose PNETs with a relatively high sensitivity. Adequate sampling for cytomorphologic analysis and adjunct immunophenotypic studies is the key to reach a definite diagnosis, which may be limited by the small size of tumors.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author.

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

GC conceived of the study. BU, GC, and JB participated in its design. All authors participated in data acquisition. BU, GC and JB analyzed and interpreted the data. GC and JB drafted the article. All authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) (or its equivalent) of all the institutions associated with this study as applicable.

Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2013/10/1/10/112648

REFERENCES

- Differences in survival by histologic type of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1766-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic diagnosis of pancreatic endocrine tumors by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration: A review. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:649-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinicopathologic features and treatment trends of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: Analysis of 9,821 patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1460-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas: Endoscopic diagnosis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:638-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Localization of pancreatic endocrine tumors by endoscopic ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1721-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Usefulness of EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) in the diagnosis of functioning neuroendocrine tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:291-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Islet cell tumor of the pancreas: Increasing diagnosis after instituting ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 2008;52:45-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration biopsy of the islet cell tumor of pancreas: A comparison between computerized axial tomography and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2002;6:106-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration.A cytopathologist's perspective. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:351-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Value of endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis of solid pancreatic masses. Gut. 2000;46:244-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pancreatic masses: A multi-institutional study of 364 fine-needle aspiration biopsies with histopathologic correlation. Diagn Cytopathol. 1998;19:423-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytological diagnosis of endocrine tumors of the pancreas by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Diagn Cytopathol. 2005;32:204-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: A study of 48 cases. Cancer. 2008;114:255-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative cytologic features of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma and islet cell tumor. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;16:112-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of endocrine neoplasms of the pancreas.Morphologic and immunocytochemical findings in 20 cases. Acta Cytol. 2004;48:295-301.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration cytology of pancreatic somatostatinoma: The importance of immunohistochemistry for the cytologic diagnosis of pancreatic endocrine neoplasms. Diagn Cytopathol. 2005;33:100-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pancreatic endocrine tumors: A large single-center experience. Pancreas. 2009;38:936-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nomenclature and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system. In: Bosman FT, Carmeiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System (4th ed). Lyon France: IARC; 2010. p. :13-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytological Ki-67 in pancreatic endocrine tumours: An opportunity for pre-operative grading. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:175-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- EUS-FNA predicts 5-year survival in pancreatic endocrine tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:907-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- E-cadherin/beta-catenin and CD10: A limited immunohistochemical panel to distinguish pancreatic endocrine neoplasm from solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas on endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspirates of the pancreas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:831-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for diagnosis of solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: A multicenter experience. Endoscopy. 2008;40:200-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology diagnosis of solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: A rare neoplasm of elusive origin but characteristic cytomorphologic features. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:654-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endosonography-guided, fine-needle aspiration cytology extending the indication for organ-preserving pancreatic surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2255-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of cytomorphology and proliferative activity in predicting biologic behavior of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: A study by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology. Cancer. 2009;117:211-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspirate microsatellite loss analysis and pancreatic endocrine tumor outcome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1474-8.

- [Google Scholar]