Translate this page into:

Pediatric fine-needle aspiration cytology: An audit of 266 cases of pediatric tumors with cytologic-histologic correlation

*Corresponding author: Dr. Sanjay Gupta, Department of Cytopathology, ICMR-National Institute of Cancer Prevention and Research, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India. sanjaydr17@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Gupta R, Sharma S, Verma S, Singh L, Gupta CR, Gupta S. Pediatric fine-needle aspiration cytology: An audit of 266 cases of pediatric tumors with cytologic-histologic correlation. CytoJournal 2020;17:25.

HTML of this article is available FREE at: https://dx.doi.org/10.25259/ Cytojournal_101_2019

Abstract

Objectives:

Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC), a well-accepted minimally invasive diagnostic technique utilized in adults, is gradually gaining ground for pediatric patients as well. However, there are very few comprehensive reports in the literature on utility of FNA in pre-operative diagnosis of pediatric tumors.

Material and Methods:

An observational study was conducted at a cancer research center and a pediatric tertiary care hospital over a 5-year period. A cytologic-histologic correlation was performed for FNACs performed in pediatric patients for a clinical diagnosis of neoplastic lesions at both the centers. Relevant clinical details and histopathology, wherever available, were retrieved. Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of FNAC in diagnosis of malignant lesion were calculated from the cases with available histologic correlation.

Results:

Of the 266 cases included, there was a slight male predominance with lymphadenopathy being the most common presentation and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma as the most frequent diagnosis in cases clinically suspected to have a neoplasm. Histologic correlation was available in 112 cases with 100% concordance in liver and kidney tumors. Few rare cytologic diagnoses such as papillary renal cell carcinoma, mesenchymal hamartoma of the liver, and thymolipoma could be accurately rendered on FNAC smears in conjunction with the clinic-radiologic features. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of FNA in diagnosing malignant pediatric tumors were found to be 100%, 92.6%, and 97.7%, respectively.

Conclusion:

The present study underscores the high sensitivity and accuracy of FNAC in diagnosis of pediatric tumors, both in superficial and deep-seated locations. Awareness of the cytomorphologic features and clinic-radiologic correlation may assist the cytopathologists in rendering a precise diagnosis of rare pediatric tumors as well.

Keywords

Fine-needle aspiration cytology

Pediatric

Histopathology

Sensitivity

Specificity

Accuracy

INTRODUCTION

Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is being increasingly used for a reliable and rapid diagnosis of palpable as well as non-palpable lumps (using image-guidance for localization) in the adults. Its introduction into the routine pediatric diagnostic algorithm has been fairly recent.[1] Although there are existing reports in the literature on utility of FNAC in the pediatric patients, the majority of such descriptions have included a specific body site or a particular disease entity.[2-4] Only occasional studies on pediatric FNAC have included both benign and malignant lesions encompassing various body sites.[5,6] The reported sensitivity and specificity of FNAC in diagnosis of pediatric lesions has varied depending on the body site included in the study.[4,7]

The present study aimed to present the cytologic-histologic correlation of pediatric FNACs from a gamut of body sites performed for a clinical diagnosis of neoplastic lesions at a cancer research center and a pediatric tertiary care hospital and assess the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of FNA in diagnosis of pediatric malignancies.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This observational study was conducted at the ICMR-National Institute of Cancer Prevention and Research, Noida, and a pediatric tertiary care hospital, Chacha Nehru Bal Chikitsalaya, Delhi, over a 5-year period (2013–2017). All FNACs performed on patients less than 14 years of age for a suspected clinical diagnosis of a neoplastic lesion were retrieved. Relevant clinical information such as site of lesion, duration of the lump, or swelling and presenting symptoms were noted from the case records. Corresponding histopathology, wherever available, was also retrieved. Cases undergoing FNAC for a reactive or infective pathology were excluded from this study.

FNAC was performed in the included cases with or without suction, as applicable depending on the site of lesion. For intra-abdominal lumps, FNAC was done under ultrasound guidance at the pediatric hospital with mild sedation and rapid on-site adequacy evaluation (ROSE) by a pathologist. For ROSE, smears were stained on-site using toluidine blue solution and examined under a microscope for cellularity. In cases, where adequate cellularity was not obtained in the first pass, a second needle pass was made and ROSE repeated. Smears prepared from the aspirated material were stained with Giemsa stain and Papanicolaou stain (as and when deemed necessary). The histopathology samples were processed as per the routine protocols and stained with H&E. Special stains and immunohistochemical panels were performed in relevant cases depending on the histopathological differential diagnoses considered. The cytology and histopathology slides of all cases were reviewed by three pathologists (RG, SS, and LS) and referred to a senior pathologist (SG) for final opinion. Cytohistologic correlation was performed based on the final opinion of the senior pathologist. Test characteristics of FNAC, that is, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for diagnosis of a malignant lesion of different body sites, were derived for the cases where histopathology diagnoses were available.

RESULTS

A total of 266 pediatric patients underwent FNAC for a clinical diagnosis of neoplasm at either of the two centers during the study period. The age range of the patients was wide (1 month to 14 years) with the median age at diagnosis being 61 months. The male: female ratio was 2.68:1. Lymph nodes constituted the most common site (127 cases, 47.7%), followed by skin and soft tissue (61, 22.9%). Other sites of FNAC included kidney, liver, abdominal masses, bone, and joints and miscellaneous locations such as salivary gland (4 cases), cheek (4 cases), mediastinum (2), thyroid (1), and testicular (1).

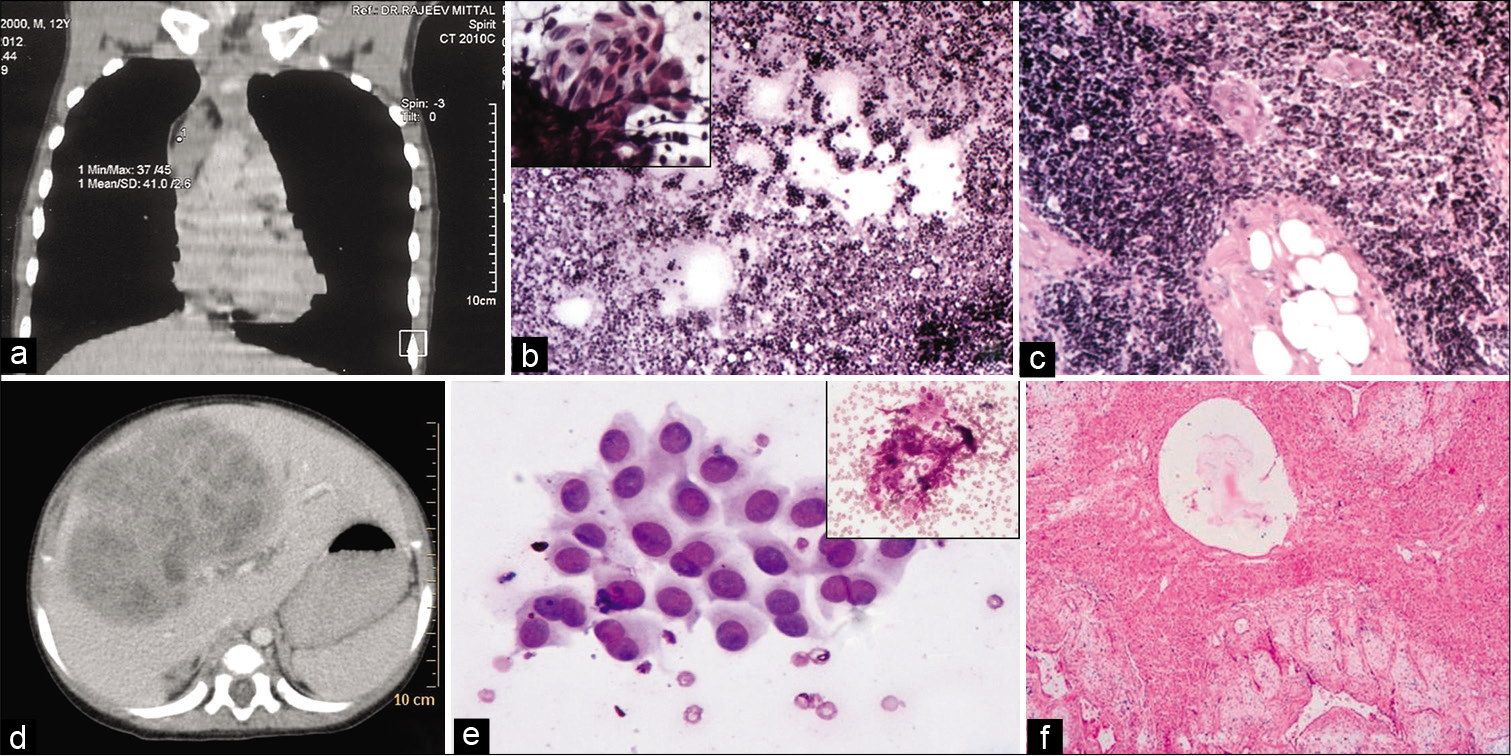

The cytological diagnoses in these 266 cases are tabulated in Table 1. Among the lymph node FNACs, the most frequent diagnosis was non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [Figure 1a and b] (62 cases), followed by Hodgkin’s disease (43 cases). The other common diagnoses in our patients included benign mesenchymal tumor (soft tissue), nephroblastoma (kidney), and neuroblastoma (abdominal mass). Three cases (one each from kidney, liver, and mediastinum) were diagnosed on cytology with the help of clinic-cytologic-radiologic correlation (papillary renal cell carcinoma, mesenchymal hamartoma, and thymolipoma, respectively) as shown in Figure 2a-f.

| Site of FNAC | Number of cases | Cytological diagnosis | No. of cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph node | 127 | NHL | 62 |

| HD | 43 | ||

| Leukemia | 10 | ||

| Mets RCT | 3 | ||

| Florid reactive hyperplasia | 9 | ||

| Skin & soft tissue | 66 | Skin appendageal tumor | 22 |

| Pilomatrixoma | 5 | ||

| Mesenchymal lesion | 27 | ||

| RCT | 3 | ||

| Lipomatous tumor | 5 | ||

| GCT of soft tissue | 4 | ||

| Kidney | 30 | Wilms’ tumor | 28 |

| Papillary RCC | 1 | ||

| RCC | 1 | ||

| Liver | 8 | Hepatoblastoma [Figure 1c and d] | 6 |

| Mesenchymal hamartoma | 1 | ||

| Mets NB | 1 | ||

| Abdominal mass | 20 | NB | 9 |

| Immature teratoma | 2 | ||

| RCT | 9 | ||

| Bone and joint | 1 | Giant cell lesion | 1 |

| Others | 12 | Mesenchymal lesion | 7 |

| Germ cell tumor | 2 | ||

| Salivary gland tumor | 2 | ||

| Thymolipoma | 1 |

FNAC: Fine-needle aspiration cytology, NHL: Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, HD: Hodgkin’s disease, Mets: Metastatic, RCT: Round cell tumor, GCT: Giant cell tumor, RCC: Renal cell carcinoma, NB: Neuroblastoma

- A panel of photomicrographs showing FNA smear from a case of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (a, Giemsa ×100) and corresponding lymph node biopsy demonstrating large cell lymphoma (b, H&E ×100). A case of hepatoblastoma on FNA displaying trabecular arrangement of cells (c, Giemsa ×40) and focal acinar arrangement (c inset) confirmed on biopsy (d, H&E ×100) and Hep-par1 staining (d inset).

- Photographs a-c demonstrate a case of thymolipoma showing a mediastinal mass in CT scan (a), FNA smear showing lymphoid cells (b, Giemsa ×40) and a fragment of epithelial cells (b inset) and excised specimen confirming the diagnosis (c, H&E ×100). A case of mesenchymal hamartoma showing a heterogeneously enhancing mass in the liver on CT scan (d), hepatocytes (e, Giemsa ×100) and stromal fragments (e inset) on FNA smear and characteristic features on biopsy (f, H&E ×40).

- A case of false positive diagnosis on FNA – aspiration cytology smear reported as suspicious for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (a, Giemsa ×100) while lymph node biopsy showed features of sinus histiocytosis (b, H&E ×100).

Histopathological follow-up could be traced in 112 cases (42.1%) in the form of biopsy or excision specimen. The cases with liver, kidney, and abdominal masses had maximum proportion of available histological specimens (87.5%, 86.7%, and 80%, respectively). The highest cytohistological correlation was seen in kidney and liver masses (100% for both), followed by lymph node (94.4%), abdominal masses (93.75%), and skin/soft-tissue lesions (90%). The results of cytohistological correlation are summarized in Table 2.

| Site of lesion | Cytologic diagnosis (no. of cases) | Histologic diagnosis (no. of cases) |

|---|---|---|

| Kidney | Wilms’ tumor (24) | Wilms’ tumor (24) |

| Papillary RCC (1) | Papillary RCC (1) | |

| RCC (1) | RCC (1) | |

| Liver | Hepatoblastoma (5) | Hepatoblastoma (5) |

| RCT (1) | Mets NB (1) | |

| Mesenchymal hamartoma (1) | Mesenchymal hamartoma (1) | |

| Lymph node | NHL (20) | NHL (18) |

| Sinus histiocytosis (2) | ||

| HD (12) | HD (12) | |

| Leukemia (4) | Leukemia (4) | |

| Abdominal mass | NB (6) | NB (6) |

| Immature teratoma (1) | Immature teratoma (1) | |

| RCT (9) | NB (3) | |

| GNB (1) | ||

| PNET (1) | ||

| RCT (4) | ||

| Skin & soft tissue | Skin appendageal tumor, not further typed (4) | Nodular hidradenoma (2) |

| Pilomatrixoma (3) | Hemangioma (2) | |

| Benign mesenchymal lesion (8) | Pilomatrixoma (3) | |

| Hemangioma (3) | ||

| Leiomyoma (3) | ||

| Fibroma (1) | ||

| RCT (2) | Myopericytoma (1) | |

| Alveolar rhabdo (1) | ||

| Lipomatous tumor (3) | RCT (1) | |

| GCT (3) | Lipoblastoma (3) | |

| GCT of tendon sheath (3) | ||

| Bone and joint | GCT (1) | Fibrous dysplasia (1) |

| Mesenchymal lesion (1) | Granulation tissue (1) | |

| Others | Germ cell tumor (1) | Yolk sac tumor (1) |

| Thymolipoma (1) | Thymolipoma (1) |

RCC: Renal cell carcinoma, Mets: Metastatic, RCT: Round cell tumor, NB: Neuroblastoma, NHL: Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, HD: Hodgkin’s disease, GNB: Ganglioneuroblastoma, PNET: Primitive neuroectodermal tumor, EIC: Epidermal inclusion cyst, rhabdo: Rhabdomyosarcoma, GCT: Giant cell tumor

Test characteristics of FNAC in diagnosis of malignancy in a pediatric setting

The overall sensitivity of FNAC for diagnosis of malignancy was 100% while the specificity was 92.6%. FNAC was found to be 97.7% accurate for the diagnosis of a malignant lesion in the pediatric age group. Accurate sub-typing of the malignant tumor was possible in 71 of 85 cases (83.5%) with cytologic-histologic correlation available.

Discordant cases

There were two false positive cases on FNAC – lymph node aspirates in these cases were reported as suggestive of NHL while the lymph node biopsy showed features of sinus histiocytosis [Figure 3 a and b]. There were no false negative cases on FNAC.

Among the histologically benign cases, cytologic-histologic discordance was seen in four cases – two cases of lobular capillary hemangioma were reported as skin appendageal tumor on FNAC; one case of fibrous dysplasia of humerus was cytologically diagnosed as giant cell tumor while another case of an organizing inflammatory lesion of the ankle was signed out as benign mesenchymal lesion on FNAC.

DISCUSSION

FNAC is an accepted minimally invasive, safe, and reliable diagnostic procedure for palpable as well as non-palpable lumps in the adult population. The use of FNAC in pediatric population has been less extensive but is gradually gaining importance as a first-line diagnostic modality, with reports being published on its safety and utility in this age group.[4] The previously reported studies have focused on FNAC of particular sites or a specific disease entity to elucidate the utility of this technique.[2-4] There have been only occasional studies including both benign and malignant lesions in pediatric FNAC.[5,6,8] However, the literature on studies encompassing the gamut of pediatric tumors in various sites, including non-palpable lesions in deep anatomical locations is scarce.[5,8] The present study, conducted at a cancer research institute and a pediatric tertiary care hospital, included both superficial/ easily accessible lumps as well as intra-abdominal or mediastinal lesions for evaluation of the diagnostic utility and test characteristics of FNAC in pediatric tumors. The FNACs were performed by trained pathologists and the technique followed in this study was similar to the practices in other countries.[8,9] For superficial masses, FNA was done with or without suction, as per the case while for the deep-seated lesions, ultrasound-guidance was utilized with ROSE conducted by the attending pathologist.

Although only about 2% of all malignancies occur in the pediatric age group, cancer constitutes an important and a leading cause of disease-related mortality among children worldwide.[6] Hence, fast and precise diagnosis of malignancies in children assumes great importance. Studies have shown variable sensitivity and specificity of FNAC in children depending on the site or lesion evaluated. An overall sensitivity of 53%, specificity of 93.3%, and accuracy of 82.1% was reported in a study of FNAC in pediatric head and neck swellings.[7] A study of thyroid FNACs in patients 18 years or younger reported a sensitivity and specificity of 94% and 100% with accuracy of 99%.[4] Cohen et al. included FNACs from a wide variety of sites and derived a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 95%.[9] In the present study, which included superficial as well as deep seated lumps of various body sites, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of FNAC for diagnosis of a suspected malignant lesion were found to be 100%, 92.59%, and 97.7%, respectively. The previously reported studies, as also our study, confirm the reliability and utility of FNACs in accurate diagnosis of pediatric tumors.

In contrast to the previous reports, the present study included only the pediatric cases where FNAC was performed for a suspected clinical diagnosis of tumors (benign or malignant). The earlier studies, whether site-specific or generalized, included all FNACs over a time period with majority of cases being reactive, inflammatory, or infective.[6-8] In our study, we found a significantly high correlation between cytologic and subsequent histologic diagnosis, especially for masses in kidney and liver, followed by lymph nodes and abdominal tumors. Only two cases of false-positive cytologic diagnosis were encountered in the present study. Lymph node biopsy in both the cases was diagnosed as reactive lymphadenitis (sinus histiocytosis). On review of the FNAC smears, both these cases were considered to be interpretative errors on cytology due to the preponderance of larger lymphoid cells from germinal centers.

The 27 histologically-proven benign lesions were diagnosed correctly as benign on FNAC. However, the cytologic typing was less than accurate when compared with the corresponding histologic diagnoses. Only eight cases (three each of pilomatrixoma and giant cell tumor and one each of hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma and thymolipoma) were accurately typed on FNAC. Further cytologic typing could not be performed in cases of benign mesenchymal tumors and lipomatous lesions. Cytohistologic discordance in tumor typing was noted in four cases – two of lobular capillary hemangioma (diagnosed as skin appendageal tumor possibly due to the clinical finding of lump associated with skin and cytological presence of few fragments of plump cells with moderate amount of cytoplasm, central round normochromatic nucleus with minimal pleomorphism), one of fibrous dysplasia (reported as giant cell tumor on cytology since the fibrous tissue was not represented in aspiration smears), and one case of inflammatory granulation tissue that was signed out as benign mesenchymal lesion, probably due to the moderate cellularity of smears composed predominantly of spindle cells with benign-appearing features. Similar results have been reported in earlier studies on the application of FNAC to diagnosis of pediatric lesions.[10,11]

However, the significant finding in our study was the correct recognition of benign lesions as benign on FNAC, obviating unnecessary anxiety associated with an incorrect malignant diagnosis. We would also like to emphasize the precise FNAC diagnosis of certain uncommon entities such as thymolipoma and hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma that became possible with clinic-radiologic correlation. An accurate cytologic diagnosis in these cases helped the pediatric surgeons in clinical decision-making for further management. The cytologic diagnosis of these cases has been reported previously in the literature.[12,13]

FNAC allowed accurate sub-typing of tumors in 83.5% of the histologically-proven malignant lesions in the present study. Problems in tumor sub-typing were encountered in round cell tumors (in non-renal locations) and abdominal germ cell tumor. Studies have shown the utility of ancillary techniques on cell blocks prepared from FNAC material in further sub-typing of malignant tumors.[14] However, in the present study, cell blocks were not prepared. With increasing availability and improving efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs leading to changing role of pre-operative neoadjuvant chemotherapy, accurate cytologic sub-typing of tumors provides an opportunity to the clinician in achieving effective tumor response.[15] However, there still would be a fraction of cases that would not be amenable to sub-typing on cytology and this should be kept in mind by both the cytopathologist and the referring clinicians.

CONCLUSION

The present study re-emphasizes the efficacy of FNAC in pre-operative diagnosis of pediatric tumors. Cytopathologists should be aware of the characteristic features of the commonly encountered as well as rare tumors in this age group to be able to render a precise diagnosis as well as sub-typing of tumors, wherever possible. This would facilitate timely appropriate management of the patients and reduce the morbidity and mortality from malignancies in the pediatric age group.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author.

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

RG conceived and designed the study, participated in sign-outs at both study sites, performed data analysis, wrote, and revised the manuscript. SS and SV performed FNA at the pediatric hospital, collected data, assisted in sign-outs, and data analysis. LS performed sign-outs at the pediatric hospital, performed cytologic-histologic correlation, assisted in data analysis, and critically reviewed the manuscript. CRG was the clinician in-charge of patients undergoing surgery at the pediatric hospital, provided clinical data, helped in literature review, and critically reviewed the manuscript. SG conceptualized the study, performed sign-outs of cases at cancer research center, performed cytohisto correlations, helped in draft and critical review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from the Institutional Review Board of the institution associated with this study. Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

FNAC - Fine needle aspiration cytology

NHL - Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

ROSE - Rapid on-site adequacy evaluation.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (the authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

References

- Evaluation of fine needle aspiration biopsy as a diagnostic tool in pediatric head and neck lesions. Pathol Lab Med Int. 2010;2:131-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cytological evaluation of head and neck tumors in children--a pattern analysis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:434-46.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of peripheral lymphadenopathy in children. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006;23:549-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Histologic and clinical follow-up of thyroid fine-needle aspirates in pediatric patients. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124:467-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration in pediatric patients 12 years of age and younger: A 20-year retrospective study from a single tertiary medical center. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:600-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spectrum of pediatric tumors diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e5480.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattern of pediatric fine needle aspiration cytology and its utility in management of head and neck swellings in a tertiary hospital in Northwestern Nigeria. Ann Afr Med Res. 2019;2:53.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology: A useful diagnostic tool in childhood tumors. J Surg Pak (International). 2013;18:24-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of fine needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of skin and superficial soft tissue lesions: A study of 510 cases. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2015;31:200-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of needle core biopsy and fine-needle aspiration for diagnostic accuracy in musculoskeletal lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:759-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aspiration cytology of mesenchymal hamartoma of the liver: Report of a case and review of literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:434-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thymolipoma in child: A case diagnosed by correlation of ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNAC) cytology and computed tomography with histological confirmation. Cytopathology. 2014;25:278-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of paediatric soft tissue tumours highlighting challenges in diagnosis of benign lesions and unusual malignant tumours. Cytopathology. 2019;30:301-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic accuracy of fine needle aspiration biopsy in pediatric small round cell tumors. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:573.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]