Translate this page into:

An elderly man with a solitary liver lesion

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

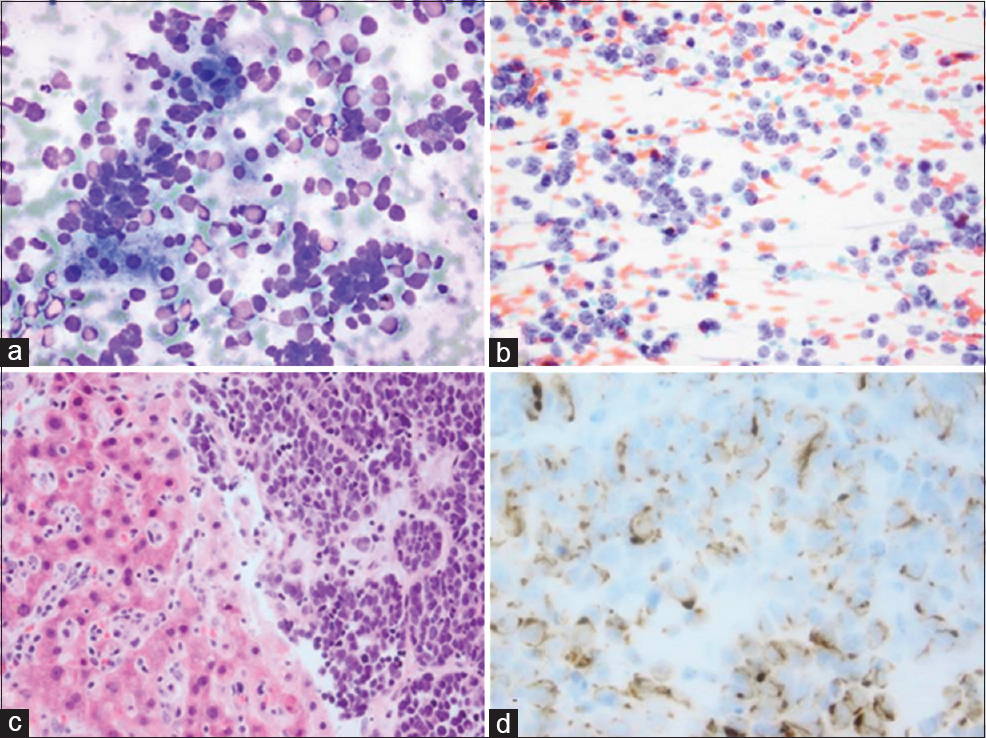

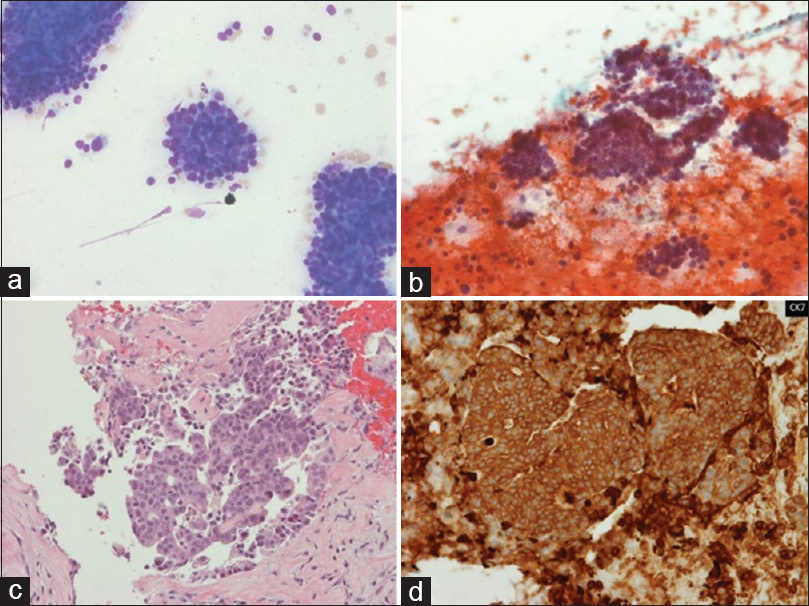

A 77-year-old Caucasian man was being worked up for pneumonia. He was on home oxygen and steroids for severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and had a prior biopsy of a lump on the lip at an outside facility many years ago. Computed tomography scan showed an incidental 2.3 cm liver lesion. After resolution of his acute issues, he underwent fine needle aspiration (FNA) and biopsy of the liver lesion [Figure 1].

- Morphologic findings of the liver lesion fine needle aspiration. (a) A cellular smear with loosely cohesive cells with scant cytoplasm (Romanowsky, ×20); (b) More nuclear detail and the characteristic dusty chromatin (Papanicolaou, ×20); (c) Solid nests of small round blue cells with nuclear crowding (H and E of the cell block, ×20); (d) The characteristic perinuclear dot-like pattern (Cytokeratin-20 of the cell block, ×40)

QUESTION

What is your interpretation?

-

Cholangiocarcinoma

-

Lymphoma

-

Merkel cell carcinoma

-

Small cell carcinoma.

ANSWER

C. Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

MCC is a rare, aggressive, cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor that tends to arise in sun-exposed areas of elderly patients or the setting of immunosuppression. MCC has a poor prognosis, especially when associated with lymph node involvement or metastatic disease. Since it is rare, MCC can be a challenging diagnosis when it involves a noncutaneous site. Aspiration of MCC typically yields relatively monomorphic nuclei with finely granular, dusty chromatin. Nucleoli are not easily observed. Mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies may be prominent, but necrosis is infrequent. Crush artifact and nuclear molding are not typically identified. MCC is notable among neuroendocrine tumors for its characteristic cytokeratin-20 (CK-20) positivity. This stain produces a perinuclear dot-like pattern that highlights spherical cytoplasmic inclusions composed of intermediate keratin filaments.

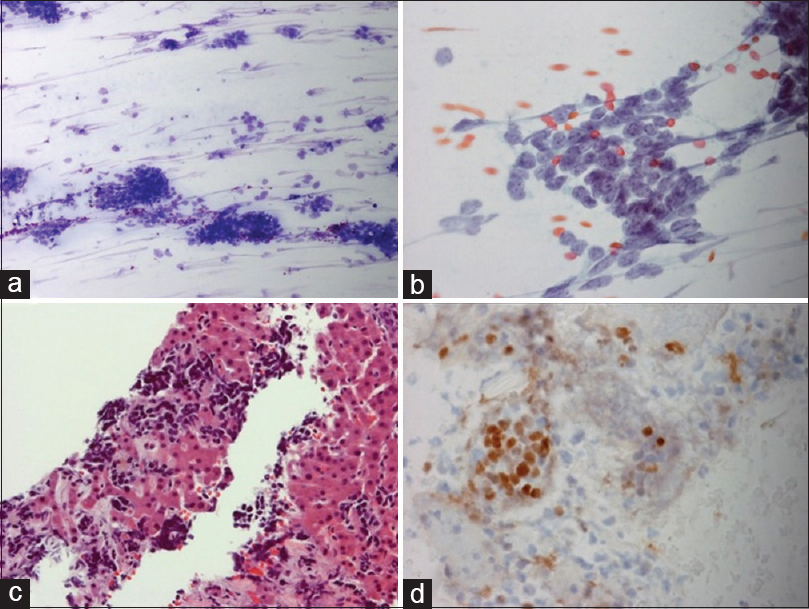

Small cell carcinoma is one of the most important differential diagnoses for MCC and is usually accompanied by a primary tumor in the lung or gastrointestinal tract. Small cell carcinoma is characterized by syncytial aggregates of cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios, prominent crush artifact, and nuclear molding. Typically, small cell carcinoma lacks CK-20 staining although it expresses neuroendocrine markers such as MCC.

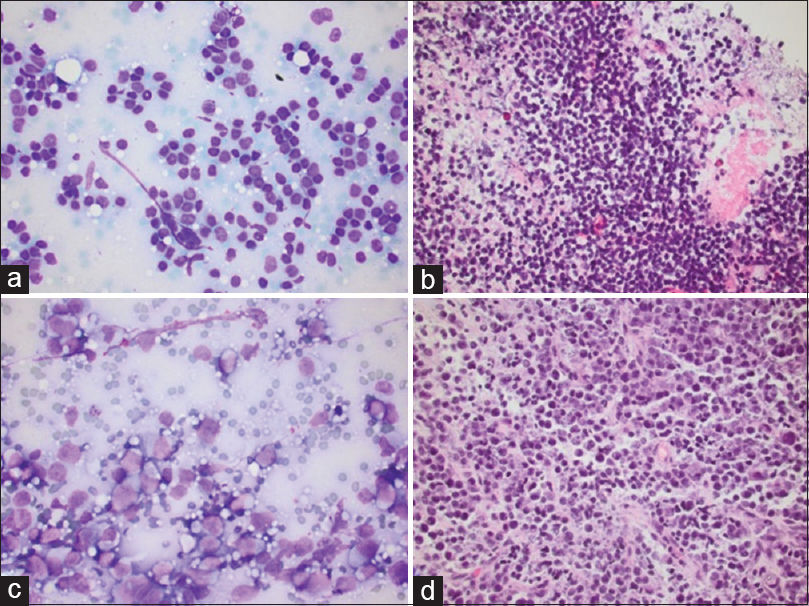

Other small cell lesions may enter the differential diagnosis of a solitary metastatic lesion sampled by FNA. Lymphomas should display a discohesive pattern with lymphoglandular bodies in the background. Unlike MCC, most lymphomas stain CD45 positive and CD56 negative; this pattern can also be seen on flow cytometry.[1] Cholangiocarcinoma was considered in our liver lesion case, but it typically displays columnar or cuboidal cells in glandular arrangements, with positivity for CK-7 and mucin stains.

Rare entities such as an undifferentiated round cell sarcoma or small cell variants of other tumors may also be considered. Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is an important differential skin lesion but is unlikely to spread to deep organs. Melanoma can metastasize widely and often is associated with skin lesions; its morphologic appearance can vary, but the loosely cohesive cells classically display a prominent nucleolus, occasional cytoplasmic pigment, and positivity for S100 and other melanoma markers. Metastatic disease should always be considered, and a good clinical history is an important first step in narrowing the differential diagnostic list.

ADDITIONAL QUIZ QUESTIONS

Q1: Which of the following is believed to be the underlying etiology in 70%–80% of MCC cases?

-

Carcinogens

-

Hereditary genetic mutations

-

Oncovirus infection

-

Trauma.

Q2: According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for MCC, a solitary distant metastasis to the liver would be classified as which of the following:

-

Stage I

-

Stage II

-

Stage III

-

Stage IV.

Q3: Which of the following immunohistochemical stain is negative in MCC?

-

CD56

-

Chromogranin

-

CM2B4

-

CK-7.

ANSWERS TO ADDITIONAL QUIZ QUESTIONS

Q1: C; Q2: D; Q3: D.

Q1: C: Research has found that 70%–80% of MCC cases are infected by a small, nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus, which was appropriately named Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV or MCV).[23] In tumors with MCPyV, the expression of viral large T antigen with an intact retinoblastoma protein (RB)-binding site is necessary for growth.[4] Recently, whole exome sequencing of MCC has detected a high number of mutations in the retinoblastoma pathway genes in all MCC cases and specifically an RB1 nonsense truncating protein mutation in polyomavirus-negative MCCs.[5]

Q2: D: Previously, five competing staging systems had been used to describe MCC in most publications. Recently, the AJCC defined a new MCC-specific consensus staging system based on tumor, node, and metastases. Stages I and II are diseases localized to the skin, with Stage I being for primary lesions ≤2 cm and Stage II being for primary lesions >2 cm. Stage III is defined as disease involving the regional lymph nodes and Stage IV as distant metastasis.[6] The 5-year disease-specific survival rate is 64%, with disease stage being the only independent predictor of survival (5-year survival for Stage I is 81%; Stage II, 67%; Stage III, 52%; and Stage IV, 11%).[7] High mitotic rate, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, positive surgical excision margins, tumor depth <5 mm, and age >75 years have also shown some correlation with a worse prognosis.[891011]

Q3: D: MCC typically expresses neuroendocrine markers such as chromogranin, CD56, and synaptophysin. Unlike most neuroendocrine lesions, though, MCC shows perinuclear positivity with CK-20. MCC is negative for CK-7. CM2B4, a relatively new marker that targets MCPyV T-antigen, is expressed in most cases.[1213]

BRIEF REVIEW OF THE TOPIC

Merkel cells are part of a neurite complex important for light-touch responses in the somatosensory system, located in the stratum basale of the epidermis.[1415] Human Merkel cells were first described by Merkel in 1875 and named Tastzellen, translating to “touch cells.”[16] MCC was first described as “trabecular carcinoma of the skin” in 1972, and electron microscopy subsequently demonstrated cytoplasmic granules, suggesting an origin from Merkel cells.[17] The term MCC was first used in 1980[18] and is now the most common term for this entity.[19] 70%–80% of MCC cases are related to the MCPyV, and the remaining polyomavirus-negative tumors are associated with mutations in the retinoblastoma gene.[23]

In the United States, approximately 1500 new cases of MCC are diagnosed each year,[20] and the incidence rate is increasing annually by 8%.[21] MCC typically presents in elderly patients (60–85 years old) or immunosuppressed patients, such as those with leukemia/lymphoma, advanced human immunodeficiency virus, or solid organ transplantation.[22] The majority of cases are seen in Caucasians, and the male to female ratio is approximately 5:4.[2324] MCC commonly involves sun-exposed areas of the body, especially the head and neck. An occasional association with squamous cell carcinoma has been noted.[25] Clinically, MCC presents as a pink-red to violaceous, firm, dome-shaped, solitary nodule with a shiny surface.[26] MCC grows rapidly and ulceration may occur.[27] Most MCC cases occur in the sun-exposed head and neck region, and those arising on sun-protected sites (such as in the oral cavity[28] or genital region[29]) have a particularly poor prognosis. The five most common clinical features are summarized in the acronym AEIOU: Asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, Expanding rapidly, Immunosuppression, Older than age 50, and Ultraviolet (UV) light-exposed site.[30]

Initial diagnosis of MCC is usually based on skin biopsy. Histologic sections reveal a dermal nodule that infiltrates the subcutaneous fat but spares the epidermis and adnexal structures.[25] Three histologic subtypes are recognized: (a) Intermediate cell type, with solid nests with trabeculae at the periphery, (b) small cell type, with sheets of small cells with a diffusely infiltrative pattern, and (c) trabecular type, with connective tissue separating interconnected cellular trabeculae. A lymphocytic infiltrate may surround or infiltrate the tumor cells. MCCs frequently contain areas that histologically resemble BCC, with mucinous stroma or artifactual stromal retraction. The most reliable histologic feature to distinguish BCC from MCC is the absence of peripheral palisading in MCC.[3132] Immunohistochemical staining for BerEP4 is positive in BCC, but negative in MCC.[25] Treatment for skin lesions usually involves surgical excision, but local recurrence rates may be as high as 40%. Of the patients with recurrences, 75% will develop nodal or distant metastases.[25]

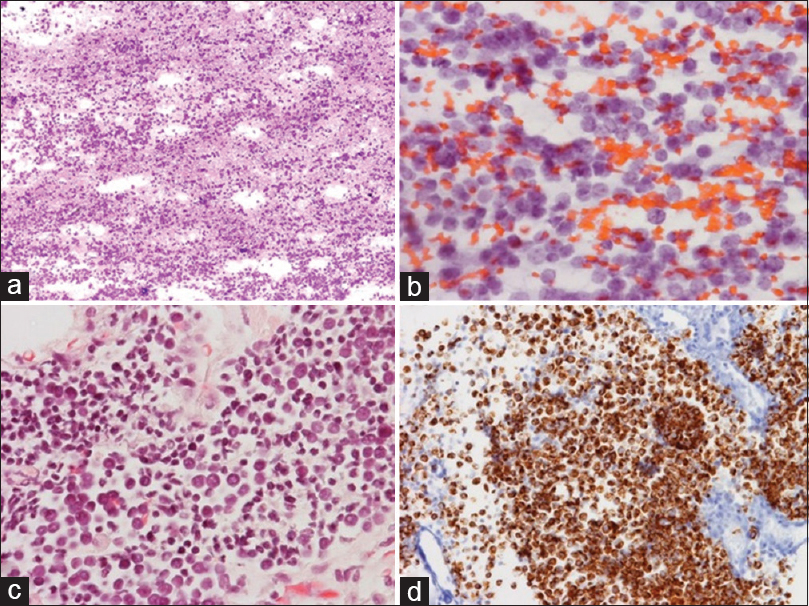

FNA can be performed to assess metastatic disease in patients with a prior diagnosis of MCC. Common FNA sites include the cervical lymph nodes, parotid gland, or axillary and inguinal nodes, with rare reported cases in the chest, proximal extremities, pancreas,[33] and ascites.[34] The reported rate of liver metastases is up to 13%,[35] yet MCC cytology specimens from the liver are seldom described in literature.[36] The presence of a solitary MCC metastasis with limited clinical history, as seen in our case, can be diagnostically challenging if one is not actively considering it. Certain cytomorphologic features may assist in identification. MCC typically yields cellular smears with numerous small round cells in a dispersed or loosely cohesive pattern [Figure 2]. The relatively monomorphic nuclei have finely granular, dusty chromatin and may show the typical endocrine “salt and pepper” appearance. Nucleoli are not easily observed. Mitotic figures may be prominent. Apoptotic bodies are often present, but necrosis is infrequent. Crush artifact and nuclear molding are not typically identified, but rare aggregates of tumor cells may infrequently produce a pseudorosette appearance. Cytoplasm is scanty or absent, and rare eosinophilic paranuclear cytoplasmic globules or buttons have been described.[3637]

- Fine needle aspiration of a solitary 5.5 cm hypermetabolic anterior mediastinum mass from a 69-year-old man with a previously resected right buttock Merkel cell carcinoma, (a) The high cellularity and loosely cohesive nature (Romanowsky, ×4); (b) The finely granular chromatin and round small nuclei (Papanicolaou, ×40); (c) Similar features (H and E of the cell block, ×40); (d) The malignant cells (Cytokeratin-20 of the cell block, ×40)

Immunohistochemistry is very important to distinguish MCC from its mimics. MCC shows a characteristic perinuclear dot-like CK-20 positivity.[3839] Small cell carcinoma [Figure 3] and other neuroendocrine tumors are typically CK-20 negative although they share neuroendocrine markers (such as chromogranin, synaptophysin, and CD56) with MCC.[1340] MCC is negative for CK-7, BerEp4, thyroid transcription factor 1, CD45, and mucicarmine; these stains distinguish it from mimics such as lymphoma [Figure 4] and cholangiocarcinoma [Figure 5]. CM2B4, a relatively new marker that targets MCPyV T-antigen, is expressed in most cases. CM2B4 is very helpful in distinguishing MCC from high-grade primary parotid neuroendocrine tumors (which regularly show CK-20 expression) and rare extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas with focal CK-20 expression.[1213]

- Small cell carcinoma involving the liver, (a) with nuclear crowding and crush artifact (Romanowsky, ×10); (b) Nuclear molding (Papanicolaou, ×40); (c) Infiltration of liver parenchyma by small dark cells with crush artifact H and E (cell block, ×20); (d) The cells stained with thyroid transcription factor 1 (shown) as well as synaptophysin and CD56 (not shown)

- Lymphoma. (a) Follicular lymphoma with a monotonous population of small lymphocytes, Romanowsky smear, ×40, with associated cell block, H and E, ×40 (b). (c) Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with large atypical discohesive cells and distinct nucleoli, Romanowsky smear, ×40, with associated cell block, H and E, ×40 (d)

- Cholangiocarcinoma. (a) Clusters of small dark cells (Romanowsky smear, ×40); (b) (Papanicolaou smear, ×20); (c) Cell block with glandular clusters of cuboidal cells (H and E, ×20); (d) Strong staining for cytokeratin-7 (×20)

In addition to surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy can improve overall survival. The combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy provide more benefit than radiation therapy alone, especially in high-risk patients.[414243] Our patient presented had severe COPD, making him oxygen dependent at home, and he opted to have radiation therapy alone secondary to his comorbidities.

In summary, MCC is a rare but aggressive malignancy with the potential for spread to the lymph nodes and distant metastasis. A solitary metastatic MCC lesion can be a challenging cytologic diagnosis, especially if limited history is available. In patients with an appropriate clinical profile (immunosuppression or elderly Caucasian men) and cytomorphology (a cellular specimen with loosely cohesive round cells with salt-and-pepper chromatin and frequent mitoses), MCC should be considered in the differential. Immunohistochemical staining for CK-20 and further inquiry into patient history can yield an appropriate diagnosis.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author. Each author has participated sufficiently in work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is a quiz case without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from the Institutional Review Board (or its equivalent).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

BCC - Basal cell carcinoma

CD - Cluster of differentiation

CT - Computed tomography

CK - Cytokeratin

FNA - Fine needle aspiration

MCC - Merkel cell carcinoma.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Coincident Merkel cell carcinoma and B-cell lymphoma: A report of two cases evaluated by cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:819-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma and Merkel cell polyomavirus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:42-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096-100.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of functional domains in the Merkel cell polyoma virus Large T antigen. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E290-300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Retinoblastoma gene mutations detected by whole exome sequencing of Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:1073-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (7th ed). New York: Springer; 2010. p. :315-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Histologic features and prognosis. Cancer. 2008;113:2549-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Analysis of clinical, histologic, and immunohistologic features of 132 cases with relation to survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5 Pt 1):734-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of 20 cases of Merkel cell carcinoma in search of prognostic markers. Histopathology. 2005;46:622-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma: A clinicopathologic study with prognostic implications. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:217-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell polyomavirus expression in merkel cell carcinomas and its absence in combined tumors and pulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1378-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Merkel cell carcinoma challenge: A review from the fine needle aspiration service. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:179-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human Merkel cells – Aspects of cell biology, distribution and functions. Eur J Cell Biol. 2005;84:259-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tastzellen and tastkoerperchen bei den hausthieren und beim menschen. Arch Mikrosk Anat. 1875;11:636-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- A cutaneous APUDoma or Merkel cell tumor? A morphologically recognizable tumor with a biological and histological malignant aspect in contrast with its clinical behavior. Cancer. 1980;46:1810-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Which are the cells of origin in merkel cell carcinoma? J Skin Cancer 2012 2012:680410.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Recent insights and new treatment options. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:141-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of postoperative radiation and chemoradiation in merkel cell carcinoma: A systematic review of the literature. Front Oncol. 2013;3:276.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma (neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin) Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;115(Suppl):S68-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: A population based study. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:20-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg's Diagnostic Surgical Pathology (5th ed). dPhiladelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010.

- Histological, immunohistological, and clinical features of merkel cell carcinoma in correlation to merkel cell polyomavirus status. J Skin Cancer 2012 2012:983421.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma of the tongue and head and neck oral mucosal sites. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:761-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the vagina with Merkel cell carcinoma phenotype. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:405-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: The AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma vs. basal cell carcinoma: Histopathologic challenges. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:789-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma frequently shows histologic features of basal cell carcinoma: A study of 30 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:612-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma metastatic to the pancreas. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:247-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma presenting as malignant ascites: A case report and review of literature. Cytojournal. 2015;12:19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemotherapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;85:2589-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic approach to a solitary liver mass composed of small round blue cells. Cytopathology. 2009;20:56-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration cytology of Merkel cell carcinoma – A review of 69 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:924-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytokeratin 20: A marker for diagnosing Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:16-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuroendocrine (Merkel-cell) carcinoma of the skin. Cytology, intermediate filament typing and ultrastructure of tumor cells in fine needle aspirates. Acta Cytol. 1987;31:267-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of small-cell lesions of the liver. Diagn Cytopathol. 1998;19:29-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comprehensive review of the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007;30:624-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Critical review with guidelines for multidisciplinary management. Cancer. 2007;110:1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of adjuvant therapy in the management of head and neck merkel cell carcinoma: An analysis of 4815 patients. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:137-41.

- [Google Scholar]