Translate this page into:

Association of immunosuppressive CD45+CD33+CD14− CD10−HLA-DR−/low neutrophils with poor prognosis in patients with lymphoma and their expansion and activation through STAT3/arginase-1 pathway in vitro

Zhimin Zhai

Huiping Wang

*Corresponding authors: Zhimin Zhai, Department of Hematology, Hematological Research Center, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, Anhui, China. zzzm889@163.com

Huiping Wang, Department of Hematology, Hematological Research Center, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, Anhui, China. wanghuiping2831@163.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Xiao M, Zhou J, Zhang W, Ding Y, Guo J, Liang X, et al. Association of immunosuppressive CD45+CD33+CD14−CD10−HLADR−/low neutrophils with poor prognosis in patients with lymphoma and their expansion and activation through STAT3/arginase-1 pathway in vitro. CytoJournal. 2024;21:69. doi: 10.25259/Cytojournal_165_2024

Abstract

Objective:

This study aimed to explore the clinical significance of CD45+CD33+CD14−CD10−HLA-DR−/low neutrophils (Cluster of Differentiation 10 [CD10−] neutrophils) in B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (B-NHL). An amplification system of CD10− neutrophils in vitro was constructed using cytokines, and the mechanisms underlying the cytokine-induced expansion and activation of the CD10− neutrophil subpopulation were investigated.

Material and Methods:

We identified a novel suppressive cell population known as CD10− neutrophils in the peripheral blood of patients with B-NHL in different statuses by flow cytometry and found it to be correlated with interleukin-6 levels, T cell counts, and plasma arginase-1 (Arg-1) levels. We then verified the effect of CD10− neutrophil expression on the prognosis of patients with B-NHL. Furthermore, we described a clinically compatible method for generating granulocyte populations rich in CD10− neutrophils using cultures of peripheral blood-isolated neutrophils supplemented with cytokines in vitro. Arg-1 expression was detected in neutrophils before and after induction by cytokines through reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and flow cytometry. T-cell proliferation and apoptosis were measured by carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester assay and Annexin V-Propidium Iodide stains, and induced cells were exposed to Arg-1 inhibitor and ruxolitinib. signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)/Arg-1 signaling was studied mainly by western blot and chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments.

Results:

We established a correlation between high CD10− neutrophil levels and poorer survival outcomes in patients with B-NHL. Moreover, CD10− neutrophils were positively correlated with interleukin (IL)-6, T-reg cells, and plasma Arg-1 levels and negatively correlated with the absolute number of total T cells. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and IL-6 could all induce the expansion of CD10− neutrophil phenotype cells in vitro, which exhibit typical immature cellular morphology, and the combination of IL-6 and GM-CSF was the most effective. We confirmed that the STAT3/Arg-1 signaling pathway could be a critical mechanism regulating CD10− neutrophil-mediated immunosuppression in vitro.

Conclusion:

CD10− neutrophils exhibited basic characteristics similar to conventional myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Our observations provide a promising STAT3 or Arg-1 targeting strategy for B-NHL and an important method for generating remarkably amounts of inhibitory granulocyte populations rich in CD10− neutrophils for immunotherapy.

Keywords

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

Lymphoma

Neutrophils

Neprilysin

Arginase

INTRODUCTION

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a heterogeneous cell subset that suppresses the immune system through different mechanisms and accumulates under pathological conditions. The common characteristics of all MDSCs include their myeloid origin, immature state, and ability to suppress T-cell response.[1,2] However, the MDSCs in humans are complex and remain a subject of debate.[3] The expansion and activation of MDSCs are mainly related to granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GMCSF), interleukin (IL)-6, and other cytokines in the tumor microenvironment.[4] One of the core pathways mediating immune suppression involves the upregulation of arginase-1 (Arg-1) by activating signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling, which inhibits T cells.[5]

Lymphoma is a group of hematological malignancies originating from lymph nodes or other lymphoid tissues. Although advances in diagnosis and treatment have improved the prognosis of this disease, a large proportion of patients still suffer from refractory or recurrent conditions.[6] In hematological malignancies, the presence and accumulation of MDSCs are often associated with disease progression and poor prognosis.[7] However, devising an optimal strategy to identify and eliminate MDSCs or alter their suppressive functions remains challenging.

Cluster of Differentiation 10 (CD10) is a cell surface neutral endopeptidase, and its expression is associated with tumors.[8] It is not expressed by immature granulocytes.[9] CD10 can serve as a marker to distinguish between mature and immature neutrophils in heterogeneous neutrophil populations in pathological environments.[10] In previous study, we identified a population of CD14− CD10− CD45+ Human Leukocyte Antigen-DR− (HLA-DR−) Side Scatter++ (SSC++) neutrophils (CD10− neutrophils) in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (B-NHL); these cells exhibited immature morphological characteristics and significantly inhibited CD3+T cells and the high expression of Arg-1 mRNA.[11] However, the origin of CD10− neutrophils and the exact mechanism by which they inhibit T cells are still unclear.

Here, we validated the clinical significance of the elevated expression of CD10− neutrophils in patients with B-NHL at different states and described a feasible method for using cytokines in vitro to promote the expansion of CD10− neutrophils which could be a useful cellular therapy product. Importantly, we demonstrate their immunosuppressive function and mechanism on CD3+T cells. The findings provide new insights into the role of CD10− neutrophils in promoting the pathogenesis of B-NHL and suggest their potential as an immunotherapy target for this disease.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Patients and healthy donors

In this study, 59 adult patients diagnosed with B-NHL (37 males and 22 females, aged 64.5 ± 1.5 years) and 47 age-/sex-matched healthy adult volunteers (27 males and 20 females, aged 59.8 ± 1.7 years) were enrolled from April 2021 to October 2023 in the Department of Hematology of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University. Among the patients, 20 were newly diagnosed (ND), 16 in remission (complete remission and partial remission [CR/PR]), and 23 in relapse/refractory (R/R). All the patients were characterized by diagnostic stratification and received standard chemotherapy.[12] The clinicopathological features of the patients are shown in Table 1. Participants with chronic infectious or diseases immune or other tumor types were excluded.

| Groups | B-NHL (ND)=20 | B-NHL (CR/PR)=16 | B-NHL (R/R)=23 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average age (range) | 64.65 (45–85) | 62.44 (39–85) | 66.35 (40–79) |

| Gender, number | |||

| Female | 6 | 7 | 9 |

| Male | 14 | 9 | 14 |

| Lymphoma type, number | |||

| DLBCL | 12 | 11 | 15 |

| FL | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| MCL | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| MZL | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| HGBL | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ann Arbor stage, number | |||

| I/II | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| III/IV | 17 | 12 | 18 |

| Risk stratification | |||

| Low risk/Intermediate risk | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| High risk | 15 | 11 | 20 |

B-NHL: B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, DLBCL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, FL: Follicular lymphoma, MCL: Mantle cell lymphoma, MZL: Marginal zone lymphoma, HGBL: High-grade B-cell lymphoma, ND: Newly diagnosed, CR/PR: Complete remission and partial remission, R/R: Relapse/refractory

Ethical approval and informed consent

This study was approved by the ethics review board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (Approval Number: 2023–091) and Jining No.1 People’s Hospital (Approval Number: KYLL-2023 11–184). Informed consent was obtained from each participant and/or their legal guardian. The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.[13]

CD10− neutrophil analysis

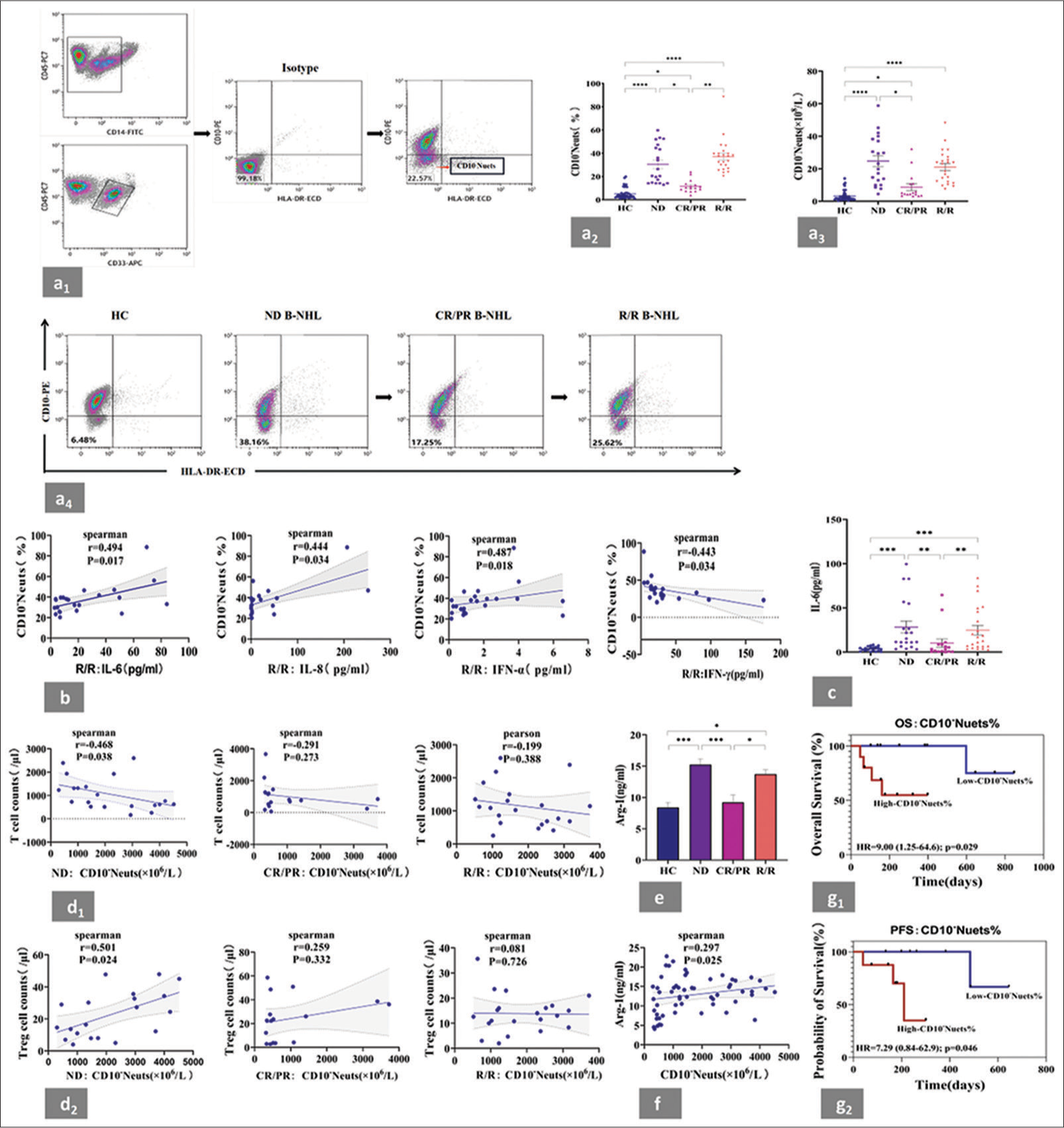

2–3 mL of peripheral blood was collected from the patients and healthy individuals and evaluated within 6 h. Afterward, 100 μL of each sample was mixed with monoclonal antibodies (ECD-conjugated HLA-DR, APC-conjugated CD33, PEconjugated CD10, FITC-conjugated CD14, and PC7-conjugated CD45; [Table 2]) and then incubated for 15 min. The samples were detected immediately by flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA) after the red blood cells were lysed using hemolysin. The CD45/CD33/CD14/CD10/HLADR antibody panel combined with forward scatter, side scatter, and multiparameter flow analysis was used. The cell population with a CD45+CD33+CD14−CD10−HLA-DR−/low was defined to be CD10− neutrophils. The specific detection and analysis methods are presented in Figure 1a1.

| Antigen | Labeling | Clone ID | Company |

|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-DR | ECD | Immu-375 | Beckman Coulter |

| CD33 | APC | RMO52 | Beckman Coulter |

| CD10 | PE | D3HL60.251 | Beckman Coulter |

| CD14 | FITC | ALB1 | Beckman Coulter |

| CD45 | PC7 | J.33 | Beckman Coulter |

| CD45 | KO | J.33 | Beckman Coulter |

| CD10 | ECD | ALB1 | Beckman Coulter |

| CD4 | PC5 | 13B8.2 | Beckman Coulter |

| CD25 | PE | B1.49.9 | Beckman Coulter |

| CD127 | FITC | R34.34 | Beckman Coulter |

| CD3 | APC-750 | UCHTI | Beckman Coulter |

| CD3 | FITC | SK7 | Mindray |

| CD8 | PE | SK1 | Mindray |

| CD45 | PerCP | 2D1 | Mindray |

| CD4 | APC | SK3 | Mindray |

| Arg-1 | APC | AlexF5 | Invitrogen |

CD: Cluster of Differentiation, HLA-DR: Human Leukocyte Antigen-DR, Arg-1: Arginase-1, ECD: Energy Coupled Dye, APC: Allophycocyanin, PE: Phycoerythrin, FITC: Fluorescein Isothiocyanate, PC7: Phycoerythrin-Cyanine 7, KO: knockout, PC5: Phycoerythrin-Cyanine 5, APC-750: Allophycocyanin-750, PerCP: Peridinin-Chlorophyll Protein

- Highly expressed CD10− neutrophils in the peripheral blood of patients with B-NHL were associated with cytokines, T cell levels, plasma Arg-1 and poor prognosis. (a1) Gating strategy of CD10− neutrophils by flow cytometry. Based on the expression of CD33, CD45, and CD14, the phenotype was selected as CD45+CD33+CD14−SSC+granulocyts. Isotype control antibody (Isotype) was taken as a negative control. Finally, the CD45+CD33+CD14−CD10−HLA-DR−SSC+ population corresponding to the CD10− neutrophil subset was circled according to the expression of CD10 and HLA-DR. All data were acquired and analyzed by Software CytExpert (2.0). (a2 and a3) Statistical analysis of CD10− neutrophil percentage and absolute values in the peripheral blood from patients with B-NHL at different states and HCs. Compared with those in the HCs, significant increases in the proportions of CD10− neutrophils and their absolute cell counts were observed in the ND, CR/PR, or R/R subgroup. (a4) Representative flow cytometry plots of HC. One patient was traced, and the variation of CD10− neutrophil percentage across all clinical stages was detected. (b) IL-6 exhibited the strongest positive correlation with CD10− neutrophil levels in the R/R group compared with IL-8 and IFN-α. A negative correlation was observed between IFN-γ and CD10− neutrophil levels. (c) Statistical analysis of the serum levels of IL-6 from patients with B-NHL at different states. (d1) Correlation between CD10− neutrophil counts and T-cell counts in patients with B-NHL at different states. A negative correlation was noted between CD10− neutrophils and T cells in the ND group. (d2) Correlation between CD10− neutrophil counts and T-reg cell counts in patients with B-NHL at different states. CD10− neutrophils and T-reg cells were positively correlated in the ND group. (e) Statistical analysis of the serum levels of Arg-1 from patients with B-NHL at different states. A significant increase in plasma Arg-1 levels was observed in the ND and R/R groups compared with those in the HCs. (f) Positive correlation between CD10− neutrophils and Arg-1 levels in patients with B-NHL. (g1 and g2) According to the median value of CD10− neutrophil frequency (23.45% in the ND group and 10.22% in the CR/RR group), patients with B-NHL were further assigned to CD10− neutrophil high or low subgroup for the subsequent analysis of relevant prognostic indicators. Relatively high levels of CD10− neutrophils were associated with poor OS in ND group and short PFS in the CR/RR group. ✶P < 0.05, ✶✶P < 0.01, ✶✶✶ P < 0.001, ✶✶✶✶ P < 0.0001. B-NHL: B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, HC: Healthy controls, ND: Newly diagnosed, CR/PR: Complete remission and partial remission, R/R: Relapsed/refractory, Arg-1: arginase-1, OS: Overall survival, PFS: Progression-free survival, IL: Interleukin, IFN-α: Interferon alpha, IFN-γ: Interferon-gamma.

Serum cytokines detection

Cytometric bead arrays (CBA, R701001, RAISE CARE, Qingdao, China) were used to quantify multiple cytokines, including IL-1b, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-17, tumor necrosis factor-a, interferon (IFN)-α, and IFN-γ. 25 μL of the supernatant from centrifuged samples/standard samples was added to the working bead solution and was left in darkness for 1 h to allow the formation of “beads antibody–antigen” complex. A 25 μL of prepared phycoerythrin working solution was added to the tube containing the sample, thoroughly mixed, and left in darkness for 2 h. The fluorescence intensity of the complex was tested using flow cytometry after washing with wash buffer. Standard curves were plotted to calculate the concentration values of each indicator.

Flow cytometric analysis of T lymphocytes and T-reg cells

100 μL of peripheral blood was added to CD3-FITC, CD8-PE, CD45-PerCP, and CD4-APC antibodies or CD25-PE, CD127-FITC, and CD4-PC5 antibodies [Table 2] and allowed to stand for 15 min. Hemolysin was added to the mixture to lyse the red blood cells. T lymphocytes and T-reg cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Measurement of extracellular Arg-1 concentration by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

After the plasma of patients and health controls or cell-culture supernatants were collected, the level of Arg-1 was quantified using an ELISA kit (Cat.No RX105693H, RUIXIN BIOTECH, China). 100 μL of standards and diluted samples were added to the respective wells and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The plate was washed 3–5 times with wash buffer to remove unbound proteins. The detection antibody was added to each well, followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature. The plate was washed again for 3–5 times. After the Horseradish Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was added, the plate was incubated for 1 h and washed again for 3–5 times. Substrate solution was added to each well, followed by incubation for 30 min in the dark. The color development indicated the presence of Arg-1. Stop solution was added to each well to terminate the reaction. The absorbance of the standards was plotted against their concentrations to generate a standard curve for determining the concentration of Arg-1 in the samples.

Isolation of neutrophils

2–3 mL of peripheral blood was collected from adult volunteers. Neutrophils were extracted using a neutrophil separation solution kit (Cat.No P9040, Solarbio®LIFE SCIENCES, China) and density gradient centrifugation (30 min, ×700 g, 18°C–25°C). The neutrophils were washed and resuspended in 1640 medium (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) for further experiments. In all the studies, neutrophil purity and viability were >90%.

In vitro induction of neutrophils rich in CD10− and phenotype identification

In a 5% carbon dioxide (CO2) incubator (ThermoFisher, USA), the neutrophils were cultured in 1640 medium containing 15% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) for 24, 48, and 72 h at 37°C, supplemented with different concentration gradients of cytokines including IL-6 (Cat.No 200-06), G-CSF (Cat.No 300-23), and GM-CSF (Cat.No 300-03) (all from Pepro Tech, USA). The proportion of CD10− neutrophils in the culture system was assessed by flow cytometry to identify the optimal cytokine and time point for inducing the CD10− neutrophil phenotype in vitro. With this optimal cytokine, different combinations of cytokines were observed at different time points to ultimately identify the optimal cytokine combination. The antibodies used (HLADR-ECD, CD33-APC, CD10-PE, CD14-FITC, and CD45-PC7) are shown in Table 2

Cell morphology assay

The smear was prepared from neutrophils before and after cytokine induction at 24 h and stained with Wright– Giemsa (BASO, BA4017, Zhuhai, China). Cell morphology was examined, and neutrophils at different differentiation stages were counted under an Olympus microscope (CX23, Olympus Corporation, Japan).

Detection of Arg-1 activity

Arg-1 activity in cell lysates was measured by visible-light spectrophotometry using an arginase assay kit (Cat.No BC5550, Solarbio® LIFE SCIENCES, China). Following the manufacturer’s instructions, a 1× Tris-HCl buffer was prepared and added with 2 mM MnCl2, and the cell lysates (ultrasonic treatment: 200 W, ultrasound 4 s, interval 10 s, repeated 25 times; Model JY92-IIDN, Ningbo, SCIENTZ, China). After incubating the reaction mixture in a constant temperature (37°C) water bath for 30 min, added the stop reaction reagent and color reagent. Measured the absorbance using a 540 nm spectrophotometer. The absorbance and standard curve were used to calculate Arg-1 activity.

Flow cytometric analysis of intracellular Arg-1 expression

The collected cells were incubated with CD45-KO, CD10-ECD, and CD14-FITC antibodies [Table 2] for 15 min. In the negative reagent control tubes, isotype-matched irrelevant antibodies were used instead of the primary antibodies. After being immersed in a membrane-breaking fixative solution for 20 min, the samples were incubated with an APC-conjugated Arg-1 monoclonal antibody. Signals were detected by flow cytometry.

Inhibiting the proliferation of autologous CD3+T cells in vitro

CD3+T cells were isolated from the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy individuals using a Human Pan T Cell Isolation Kit (Cat.No 130-096-535, Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) and then stimulated with CD3 (Cat. No 16-0037-85)/CD28 (Cat.No 16-0280-85) monoclonal antibodies (1 μg/mL, eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). After incubation with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Cat.No 34554, 2.5 μM, Invitrogen, USA) at 37°C for 30 min, the CD3+T cells were cocultured or indirectly cocultured with autologous neutrophils at ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:4. After 48 h, the cells were collected and stained with CD45-KO and CD3-APC-750 [Table 2]. Flow cytometry was used to measure the CFSE intensity and proliferation rate of the CD3+T cells. CD3+T cells without CD3/CD28 monoclonal antibody stimulation were used as negative control.

T-cell apoptosis assay

Annexin V-Propidium Iodide (V-PI) staining assay (Annexin V-Allophycocyanin/Propidium Iodide Apoptosis Kit; Cat.No E-CK-A217, Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) was performed to measure apoptosis. The isolated CD3+T cells were cocultured or indirectly cocultured with autologous neutrophils at ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:4 for 48 h. The cells were then stained with CD3-FITC, CD45-PC7 [Table 2], and annexin V-PI reagent to measure apoptotic CD3+T cells by flow cytometry.

Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay

RT-PCR was used to detect the relative mRNA expression levels of STAT1, STAT3, STAT5, and Arg-1 in neutrophils before and after cytokine induction. Total RNA was extracted from each experimental group using an RNeasy kit (Cat.No 74104, Qiagen, Dusseldorf, Germany). Reverse transcription and product amplification were completed using an assay kit from Vazyme Biotech (Cat.No R323, Nanjing, China) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The primer sequences used in the experiment are shown in Table 3.

| Forward primer (5'-3') | Reverse primer (3'-5') | |

|---|---|---|

| STAT1 | CAGCTTGACTCAAAATTCCTGGA | TGAAGATTACGCTTGCTTTTCCT |

| STAT3 | CAGCAGCTTGACACACGGTA | AAACACCAAAGTGGCATGTGA |

| STAT5 | CATGTACCCACAACCCTGACC | CACAACACGACCGCTTCACATTGC |

| Arg-1 | CTCAGGGGCATAGAGGTTGA | TACCATGTGTCCGATGCAGT |

| β-actin | CTCCATCCTGGCCTCGCTGT | GCTGCTACCTTCACCGTTCC |

RT-PCR: Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, STAT: Signal transducer and activator of transcription, Arg-1: Arginase-1, A: Adenosine, C: Cytosine, G: Guanine, T: Thymine

Pharmacologic inhibitor treatment

For STAT/Arg-1 signaling experiments, the cells were treated with 20 μM pathway inhibitors, namely ruxolitinib (HY-50856, MedChemExpress, China) or Arg-1 inhibitor (HY-15775, MedChemExpress, China) at 37°C for 48 h. The cells cultured with or without inhibitors were used for the subsequent detection of the expression and activity of Arg-1 protein and mRNA. The recovery of the immunosuppressive function of cytokine-induced neutrophils on autologous CD3+T cells was then determined after ruxolitinib or Arg-1 inhibitor supplementation through coculture and indirect coculture systems.

Western blot analysis

Proteins were extracted, denatured, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA), the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: b-actin (1 μg/mL, Cat.No AF5003, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), STAT1 (2 μg/mL, Cat.No YT4439), STAT3 (2 μg/mL, Cat.No YT4443), STAT5 (2 μg/mL, Cat.No YT4453), phospho-STAT1 (p-STAT1, 2 μg/mL, Cat.No YP0249), phospho-STAT3 (p-STAT3, 2 μg/mL, Cat.No YP0250), and phospho-STAT5 (p-STAT5, 2 μg/mL, Cat.No YP0254) (all antibodies from ImmunoWay Biotechnology, USA, except b-actin). The membranes were then washed and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1 μg/mL, Cat. No31460, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). Finally, the target protein was detected using an Electrochemiluminescent. Plus detection reagent (Tanon, Shanghai, China). Grayscale values were evaluated using ImageJ v1.47.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

Chromatin DNA preparation and ChIP assay were carried out in accordance with the protocol of the ChIP kit (Cat. No Bes5001, BersinBioTM, Guangzhou, China). The IgG (Cat.No AB171870, 8 μg) and Arg-1 (Cat.No AB267373, 8 μg) groups were added with their ChIP-grade antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) using the suggested concentration from the manufacturers. The purified DNA was subjected to RT-PCR using the primers listed in Table 4 which span the potential Arg-1 binding site in the Transcription Start Site (TSS) promoter.

| Forward primer (5'-3') | Reverse primer (3'-5') | |

|---|---|---|

| Arg-1 site1 | TGGCATACAAAGAACTTTCAGG | GGCAAGAGTAACTGTTTTGCTC |

| Arg-1 site2 | CTTCTAGGCCCTGGGGATAC | TATGCCCCTGAGCTACCATT |

| Arg-1 site3 | CTCAGGGGCATAGAGGTTGA | TACCATGTGTCCGATGCAGT |

| GAPDH | AAAAGCGGGGAGAAAGTAGG | AAGAAGATGCGGCTGACTGT |

CHIP: Chromatin immunoprecipitation, Arg-1: Arginase-1, GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, A: Adenosine, C: Cytosine, G: Guanine, T: Thymine

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Differences in means and correlation analyses were assessed using parametric (two-tailed Student’s or paired t-test) or non-parametric (Mann–Whitney U or Wilcoxon’s and Spearman’s p tests) methods. Overall survival (OS: The time from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up) and progression-free survival (PFS) were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and two-tailed log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted using the Cox proportional hazards model. Variables with a P < 0.1 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate Cox model. Statistical tests were conducted using GraphPad Prism v.9.0 and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v.26.0. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

High expression of CD10− neutrophils in the peripheral blood of patients with B-NHL was associated with cytokines, T cell levels, plasma Arg-1 and poor prognosis

To assess whether CD10− neutrophils play a role in B-NHL, their frequency and absolute cell counts in the peripheral blood of the patients at different states were compared with those of the healthy donors. Compared with those of the healthy controls, significant increases in the proportions of CD10− neutrophils [Figure 1a2] and their absolute cell counts [Figure 1a3] were observed in the ND, CR/PR, or R/R subgroup. In addition, differences were noted among the patients at different states. The proportions of CD10− neutrophils in the ND and R/R subgroups were higher than that in the CR/PR subgroup. The absolute cell count of CD10− neutrophils was higher in the ND subgroup than in the CR/PR subgroup. We further verified the above trend by evaluating CD10− neutrophil levels in one patient with B-NHL throughout the entire course of the disease (from initial diagnosis to remission to relapse) using flow cytometry. The high levels of CD10− neutrophils detected at initial diagnosis significantly decreased during remission and increased again during relapse [Figure 1a4].

As shown in Figure 1b, IL-6 exhibited the strongest positive correlation with CD10− neutrophil levels in the R/R group compared with IL-8 and IFN-α. A negative correlation between IFN-γ and CD10− neutrophil levels was observed in the R/R group. No significant relationships were found for the other assessed cytokines [Supplemental Figure 1]. Similar to the case of CD10− neutrophils, the IL-6 levels in the ND and R/R groups were significantly higher than those in the CR/PR group [Figure 1c].

The tumor microenvironment is dominated by immune suppressive cells and lacks effector T cells. Therefore, the correlation between the absolute cell counts of CD10− neutrophils and T-cell or T-reg cell counts in the patients with B-NHL was analyzed. In the ND group, the CD10− neutrophils were negatively correlated with the T cells [Figure 1d1] but positively correlated with the T-reg cells [Figure 1d2]. No significant correlations were found between the numbers of CD10− neutrophils and T cell or T-reg cell counts in either the CR/PR or R/R subgroup.

Compared with those of the healthy controls, the plasma Arg-1 levels were significantly increased in the ND or R/R group but not in the CR/PR group [Figure 1e]. These results indicated that elevated plasma Arg-1 levels are related to disease status. A positive correlation was noted between CD10− neutrophils and Arg-1 levels [Figure 1f] in the patients with B-NHL.

According to the median frequency of CD10− neutrophils (23.45% in the ND group and 10.22% in the CR/RR group), the patients were further divided into high or low CD10− neutrophil subgroup. As shown in Figure 1g1 and g2, relatively high levels of CD10− neutrophils were associated with poor OS in the ND group and short PFS in the CR/RR group. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses showed that CD10− neutrophils were an independent prognostic factor [Table 5]. All these results suggested that elevated circulating levels of CD10− neutrophils may be an indicator of poor prognosis in patients with B-NHL.

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR 95%CI P | HR 95%CI P | |||||

| Age(>60 vs. ≤60) | 1.004 | 0.406–2.483 | 0.993 | |||

| Gender (male vs. female) | 1.364 | 0.515–3.611 | 0.532 | |||

| Stage(III/IV vs. I/II) | 4.982 | 1.287–19.296 | 0.020 | 1.692 | 0.213–13.458 | 0.619 |

| Risk stratification (high vs. low/medium) | 14.518 | 2.882–73.23 | 0.001 | 16.361 | 1.366–195.987 | 0.027 |

| IL-6 (ng/mL) | 1.029 | 1.014–1.043 | <0.001 | 1.001 | 0.991–1.030 | 0.279 |

| CD10−neutrophils% | 1.033 | 1.009–1.058 | 0.007 | 1.027 | 1.002–1.053 | 0.032 |

OS: Overall survival, B-NHL: B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, IL-6: interleukin-6, HR: Hazard ratio, 95%CI: 95% confidence interval, CD10−neutrophils: CD45+CD33+CD14−HLA-DR−CD10−cells, P:P-value

GM-CSF, G-CSF, or IL-6 stimulation induced the expansion of CD10− neutrophils from healthy adult neutrophils in vitro and the granulocyte population after induction exhibited immature morphology

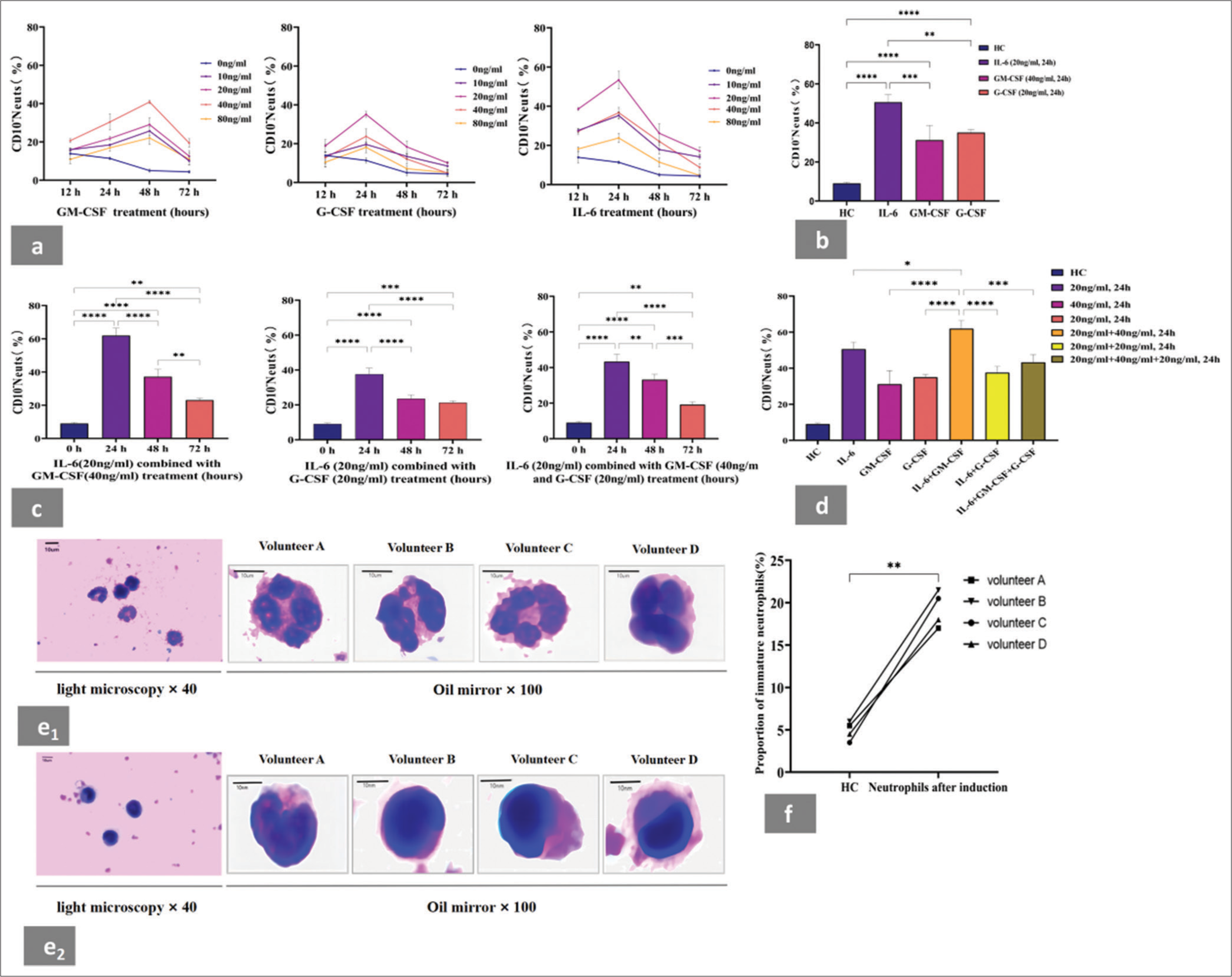

We cultured neutrophils isolated from healthy adults in concentration gradients of IL-6, GM-CSF, and G-CSF (0, 10, 20, 40, and 80 ng/mL) for 12, 24, 48, and 72 h. The phenotype of the CD10− neutrophil subset was characterized as CD45+CD33+CD14-CD10−HLA-DR−/low, and the percentage of CD10− neutrophils was further detected through flow cytometry. We found that the treatment of neutrophils with cytokines resulted in a marked increase in CD10− neutrophil percentage compared with neutrophils without cytokine stimulation [Figure 2a]. Moreover, the neutrophils in the presence of IL-6 (20 ng/mL) showed a higher CD10− neutrophil percentage than the neutrophils treated with GMCSF (40 ng/mL) or G-CSF (20 ng/mL) for 24 h [Figure 2b]. Next, we used different combinations of IL-6 (20 ng/mL), GM-CSF (40 ng/mL), or G-CSF (20 ng/mL) to stimulate neutrophils in vitro [Figure 2c]. The final data showed that compared with the other combinations, IL-6 (20 ng/mL) combined with GM-CSF (40 ng/mL) significantly increased the proportion of CD10− neutrophils at 24 h [Figure 2d].

- IL-6, GM-CSF, or G-CSF stimulation induced the expansion of CD10− neutrophils in vitro. Cell morphological assessment in neutrophils population before and after induction by cytokines. (a) GM-CSF, G-CSF, and IL-6 could all induced the expansion of neutrophils to the CD10− neutrophil phenotype in vitro. (b) Neutrophils in the presence of IL-6 (20 ng/mL) showed higher CD10− neutrophil percentage than those treated with GM-CSF (40 ng/mL) or G-CSF (20 ng/mL) for 24 h. (c) Proportion of CD10− neutrophils induced in vitro by stimulation with different cytokine combinations at different time points. (d) Proportion of CD10− neutrophils induced by IL-6 (20 ng/mL) combined with GM-CSF (40 ng/mL) was higher than that induced by other cytokine combinations at 24 h. (e1) Wright–Giemsa staining revealed that the neutrophil population before induction showed mature cellular morphology. This trend was further validated by evaluating the morphology of neutrophils in the same four volunteers. (e2) Wright–Giemsa staining revealed that the neutrophil population after induction showed immature cellular morphology. This trend was further validated by evaluating the morphology of neutrophils in four volunteers. (f) Proportion of immature granulocytes in neutrophil population before and after induction. The percentage of immature cells in neutrophils after induction was significantly higher than that before induction. Each experiment was repeated 3 times. ✶P < 0.05, ✶✶P < 0.01, ✶✶✶P < 0.001, ✶✶✶✶P < 0.0001. HC: Healthy control, GM-CSF: Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor, G-CSF: Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, IL-6: Recombinant human interleukin-6. Pictures were captured though an Olympus CX23 microscope (OLYMPUS, Tokyo, Japan).

Before induction, the neutrophils were primarily composed of mature granulocytes [Figure 2e1]. Wright–Giemsa staining showed that the neutrophils induced by cytokines with a high proportion of CD10− neutrophils exhibited typical immature cellular morphology [Figure 2e2]. We also analyzed the percentage of immature cells in neutrophils before and after induction. The percentage of immature neutrophils after induction was 19.5%, which was significantly higher than that before induction (4.87%; [Figure 2f]).

CD10− neutrophil-rich population stimulated by cytokines in vitro suppressed T-cell response in an Arg-1-dependent manner

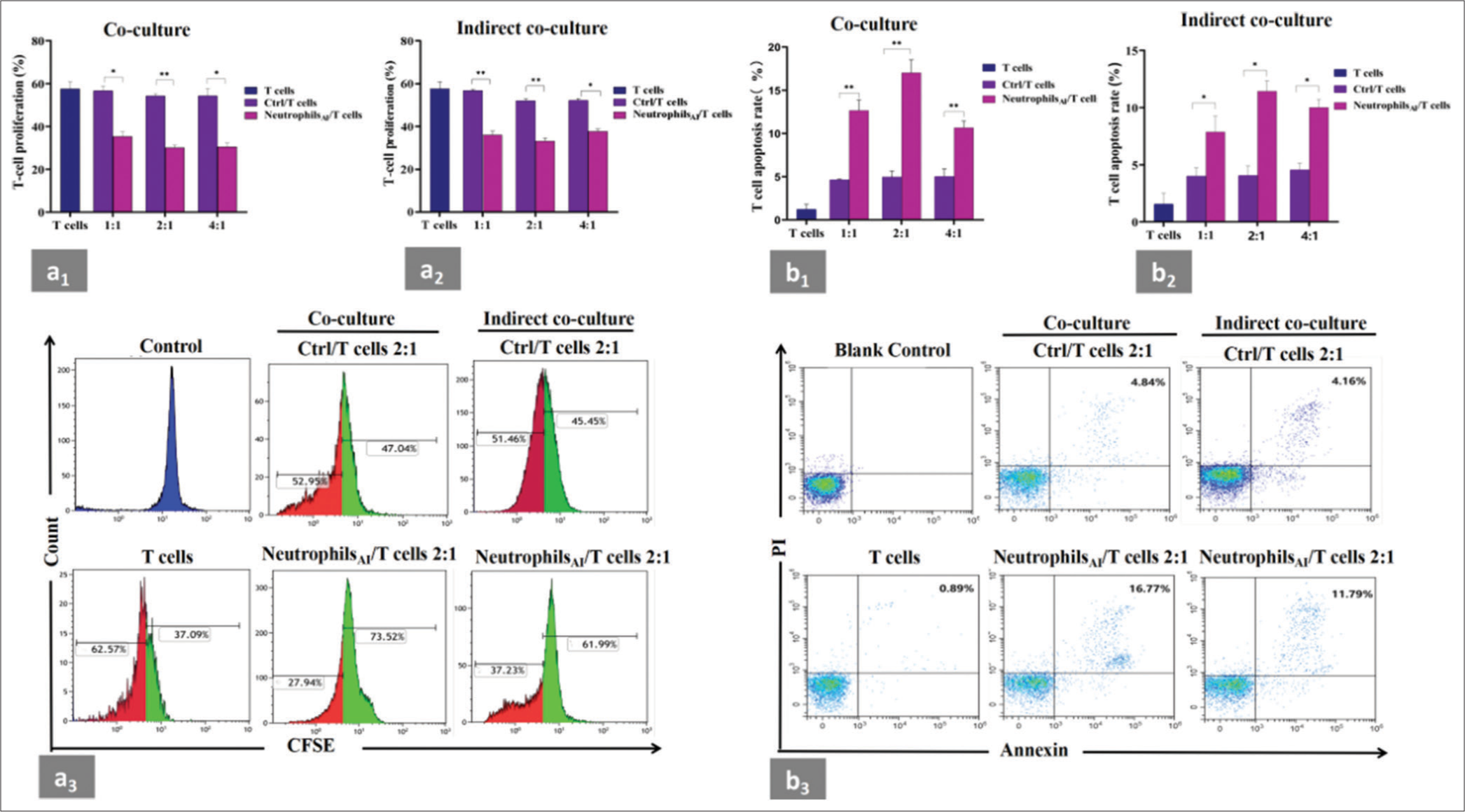

G-MDSCs suppress antitumor immune responses by inhibiting cytotoxic T cell function under certain pathological environments.[14,15] Therefore, we assessed the effect of cytokine-induced neutrophils on T-cell responses [Figure 3a1-a3, Supplemental Figure 2a]. First, neutrophils were cocultured with autologous CD3+T cells at different ratios for 48 h. The results showed that the proliferation of CD3+T cells was suppressed by neutrophils after induction (represented by neutrophilsAI) compared with that before induction (represented by Ctrl) in the coculture system. Second, CD10− neutrophils were indirectly cocultured in a Transwell chamber to determine whether they exert their function through direct contact with CD3+T cells. The neutrophilsAI in the indirect coculture system still had a significant inhibitory effect on CD3+T-cell proliferation. This finding suggested that the induced neutrophil population rich in CD10− neutrophils may exert their suppressive function on CD3+T cells by secreting immune mediators into the supernatants. We found that the ratio of 2:1 for neutrophilsAI/CD3+T cells resulted in a greater inhibitory effect on CD3+T-cell proliferation compared with other ratios under coculture and indirect coculture. These experimental results demonstrated that CD10− neutrophils actively suppress CD3+T cells through direct or indirect contact.

- Suppression of neutrophils induced by cytokines on autologous CD3+T cells. (a1 and a2) CD3+T cells from healthy donors were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 and cocultured or indirectly cocultured with neutrophils before and after induction from the same donors at different ratios for 48 h. T-cell proliferation was evaluated by CFSE labeling. Unstimulated CD3+T cells were used as a negative control. The samples were analyzed by flow cytometry. The neutrophils after induction had significant inhibitory effects on CD3+T-cell proliferation in the coculture and indirect coculture systems and the ratio of 2:1 for induced neutrophils/CD3+T cells resulted in a greater inhibitory effect on CD3+T-cell proliferation compared with other ratios. (a3) Representative flow cytometry data of CD3+T-cell proliferation experiment from one individual in the coculture or indirect coculture system. The ratio of neutrophils/CD3+T cells was 2:1. The red area represented the proliferating fraction of CD3+T cells. (b1 and b2) CD3+T cells were cocultured or indirectly cocultured with neutrophils before and after induction from the same donors at different ratios for 48 h, and apoptotic CD3+T cells were assessed by flow cytometry. CD3+T cells cultured alone were used as a negative control. The induced neutrophils significantly induced the apoptosis of CD3+T cells in the coculture and indirect coculture systems compared with the neutrophils before induction. The total apoptotic ratio of CD3+T cells in the group with induced neutrophil/CD3+T cell ratio of 2:1 was higher than that in the other groups. (b3) Representative flow cytometry data of CD3+T cell apoptosis experiment from one individual in the coculture or indirect coculture system. The ratio of neutrophils/CD3+T cells was 2:1. CD3+T cells without PI or annexin V were used as a blank control. Apoptotic T cells were marked as CD3+/Annexin+/PI+. Each experiment was repeated 3 times. ✶P < 0.05, ✶✶P < 0.01. CFSE: Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester, Ctrl: Neutrophils before induction, neutrophilsAI: Neutrophils after induction.

We also conducted an annexin V-PI apoptosis assay on autologous CD3+T cells to determine if CD10− neutrophils increase cell death. We observed that neutrophilsAI significantly induced the apoptosis of CD3+T cells at 48 h in the coculture and indirect coculture systems [Figure 3b1-b3 and Supplemental Figure 2b] compared with the neutrophils before induction under the same conditions. The total apoptotic ratio of CD3+T cells in the group with neutrophilAI/CD3+T cell ratio of 2:1 was higher than that in the other groups.

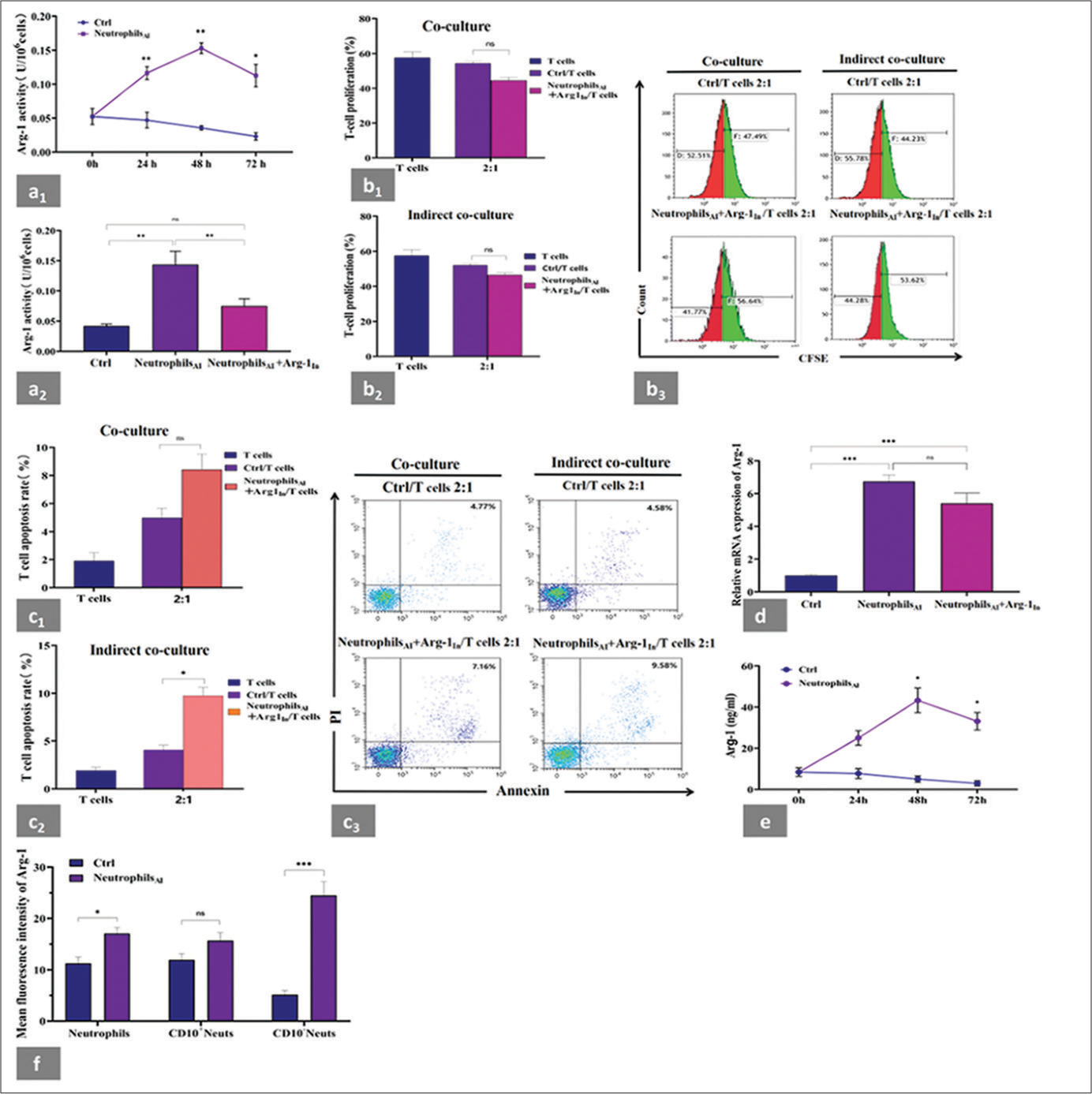

The L-arginine degradation of MDSCs through Arg-1 impairs T-cell responsiveness under certain pathological conditions.[16] We further investigated the potential mechanism of regulating CD10− neutrophil-mediated T-cell suppression. We measured Arg-1 activity, Arg-1 mRNA expression, and the intracellular and extracellular protein levels of Arg-1 in the neutrophil population before and after induction. A remarkable increase in Arg-1 activity was observed in neutrophilsAI compared with that before induction at different time points [Figure 4a1], and this effect was most striking at 48 h. The above tendencies were again validated in neutrophilsAI treated with an Arg-1 inhibitor (represented by Arg-1In) for 48 h, where the Arg-1 activity almost completely recovered to the normal level [Figure 4a2]. Neutrophil/CD3+T-cell coculture and indirect coculture experiments were conducted in the presence of Arg1In to further investigate this mechanism. The results indicated that CD3+T-cell proliferation [Figure 4b1-b3] and apoptosis [Figure 4c1-c3] at a neutrophilAI/CD3+T-cell ratio of 2:1 were significantly reversed at 48 h. No remarkable changes in CD3+T-cell apoptosis were observed in the indirect coculture system under the same conditions. The mRNA expression of Arg-1 was upregulated in neutrophilsAI compared with that before induction at 48 h. No substantial differences were observed between the induced neutrophils treated with or without Arg-1In [Figure 4d].

- Suppression of neutrophils induced by cytokines on autologous CD3+T cells and changes in the expression and activity of Arg-1. (a1) Arg-1 activity was determined at different time points in neutrophils before and after induction. A significant increase in Arg-1 activity was observed in neutrophilsAI compared with that before induction, and this effect was most striking at 48 h. (a2) Changes of Arg-1 activity in neutrophilsAI with or without Arg-1In compared with that before induction at 48 h. Arg-1 activity almost completely recovered to the normal level in neutrophilsAI with Arg-1In. (b1 and b2) Autologous CD3+T cells were cocultured or indirectly cocultured at a 1:2 ratio with neutrophils before induction or with induced neutrophils treated with Arg-1 inhibitor from the same donors for 48 h. CD3+T-cell proliferation was significantly reversed to healthy control levels at 48 h in neutrophilsAI treated with Arg-1In. (b3) Representative flow cytometry data of CD3+T-cell proliferation. (c1 and c2) CD3+T cells were cocultured or indirectly cocultured at a 1:2 ratio with neutrophils before induction or with induced neutrophils treated with Arg-1 inhibitor from the same donors for 48 h. CD3+T-cell apoptosis was significantly reversed to healthy control levels at 48 h in neutrophilsAI treated with Arg-1In in the coculture system but not in the indirect coculture system. (c3) Representative flow cytometry data of CD3+T cell apoptosis. (d) Changes of mRNA expression of Arg-1 in neutrophilsAI with or without Arg-1In compared with neutrophils before induction at 48 h. mRNA expression of Arg-1 was upregulated in neutrophilsAI. However, no substantial differences were observed between induced neutrophils treated with or without Arg-1In. (e) Extracellular production of Arg-1 protein was evaluated by ELISA at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h in neutrophils before and after induction. Extracellular Arg-1 levels of neutrophilsAI were significantly higher at 48 and 72 h than that of neutrophils before induction. (f) Changes of intracellular Arg-1 fluorescence intensity were detected by flow cytometry in neutrophils before and after induction at 48 h. Intracellular expression of Arg-1 in neutrophils was higher after induction than before induction and was dominated by the CD10− neutrophil population. Each experiment was repeated 3 times. ✶P < 0.05, ✶✶P < 0.01, ✶✶✶P < 0.001, ns: P > 0.05. CFSE: Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester, Ctrl: Neutrophils before induction, Neutrophilsai: Neutrophils after induction, Arg-1In: Arg-1 inhibitor, PBMCs: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells, Arg-1: arginase-1, CD10− neutrophils: CD45+CD33+CD14-HLA-DR-CD10-cells, CD10+Neutrophils: CD45+CD14-CD33+HLA-DRCD10+cells, ELISA: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

We further compared the extracellular and intracellular expression of Arg-1 protein in neutrophils before and after cytokine stimulation using ELISA and flow cytometry, respectively. In line with the trend of Arg-1 activity, the extracellular production of neutrophilsAI was expressed at a significantly high level at 48 h [Figure 4e]. As shown in Figure 4f, the intracellular expression of Arg-1 in neutrophils after induction for 48 h was higher than that before induction. To further verify whether Arg-1 expression is dominated by the CD10− neutrophil population after induction, we used a flow cytometry gating strategy to circle two groups of cells, CD10− neutrophils and CD10+ neutrophils (CD45+CD33+CD14−CD10+HLA-DR−/low) from the neutrophil population [Supplemental Figure 3a]. Compared with those before induction, the CD10− neutrophils had significantly increased Arg-1 expression after induction. No difference in Arg-1 expression was observed in CD10+ neutrophils before and after induction [Figure 4f]. We demonstrated the above variation trends using single sample flow cytometry analysis [Supplemental Figure 3b].

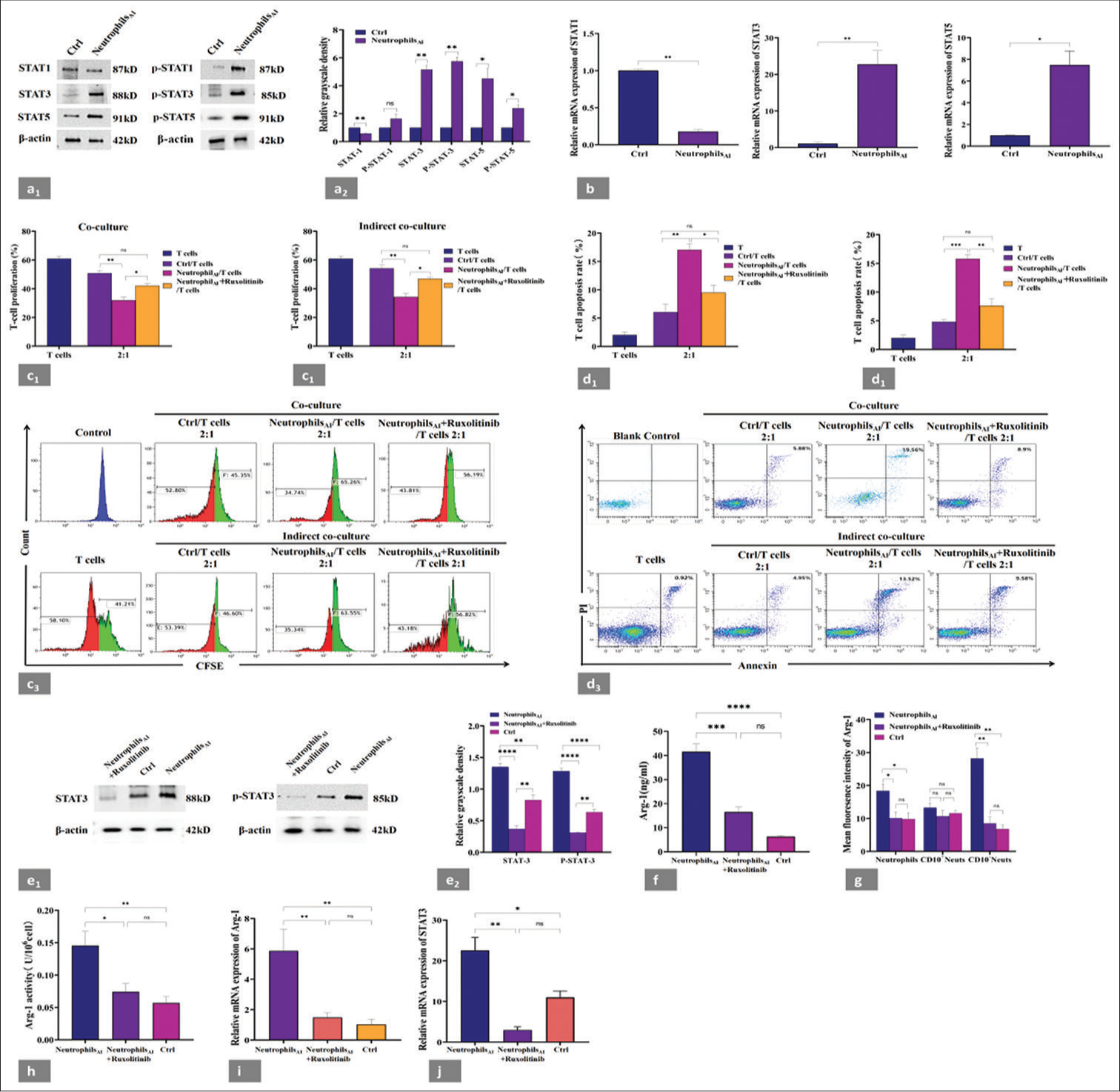

Increased activity of STAT3 pathway, which is required for T-cell suppression

STAT family proteins are crucial in regulating the expansion and activation of MDSCs under tumor and other conditions.[5,17] To investigate which signaling pathway is responsible for the enhanced Arg-1 production and activation in CD10− neutrophils, we analyzed the activity of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 in neutrophils before and after induction for 48 h [Figure 5a1 and a2]. An increased expression for STAT3, STAT5, p-STAT3, and p-STAT5 in neutrophils AI compared with those before induction, indicating the increased activation of STAT3 and STAT5, especially STAT3. We also validated these findings at the gene expression levels of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 [Figure 5b].

- Increased activity of STAT3, which is required for T-cell suppression. (a1) Neutrophils before and after induction were tested for STAT1, STAT3, STAT5, p-STAT1, p-STAT3, and p-STAT5 expression by WB. (a2) Grayscale analysis of WB results by image J software; the result was expressed as the gray value of the target band/the gray value of the reference protein. Increased expression levels of STAT3 and p-STAT3 proteins were found in neutrophilsAI compared with those before induction. (b) Changes of mRNA expression of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 in neutrophils before and after induction. The mRNA level of STAT3 in neutrophilsAI was significantly higher than that in neutrophils before induction. (c1 and c2) Induced neutrophils with or without ruxolitinib were cocultured or indirectly cocultured with autologous CD3+T cells from the same donors at 2:1 ratio for 48 h; T-cell proliferation was evaluated by CFSE labeling, and unstimulated T cells were used as a negative control. The samples were analyzed by flow cytometry. Ruxolitinib addition almost completely abolished the ability of CD10− neutrophils to suppress T-cell proliferation. (c3) Representative flow cytometry data of T-cell proliferation from one individual in coculture and indirect coculture systems. The red area represented the proliferating T-cell fraction. (d1 and d2) Induced neutrophils with or without ruxolitinib were cocultured or indirectly cocultured with autologous CD3+T cells from the same donors at 2:1 ratio for 48 h, and apoptotic T cells were assessed by flow cytometry. CD3+T cells cultured alone were used as a negative control. Ruxolitinib addition almost completely prevented T-cell apoptosis. (d3) Representative flow cytometry data of CD3+T-cell apoptosis experiment from one individual in the coculture or indirect coculture system. CD3+T cells without PI or annexin V were used as a blank control. Apoptotic T cells were marked as CD3+/annexin+/PI+. (e1) WB analysis of the changes in STAT3 and p-STAT3 expression before and after ruxolitinib addition in the induced neutrophil population and (e2) grayscale analysis of WB results by imageJ software. Ruxolitinib inhibited the expression of STAT3 and p-STAT3 proteins. (f) Extracellular production of Arg-1 protein was evaluated by ELISA at 48 h before and after the addition of ruxolitinib in neutrophilsAI. Significantly decreased expression of extracellular Arg-1 in neutrophilsAI treated with ruxolitinib. (g) Changes in intracellular Arg-1 fluorescence intensity were detected by flow cytometry at 48 h before and after ruxolitinib addition in neutrophilsAI. Significantly decreased expression of intracellular Arg-1 in neutrophilsAI treated with ruxolitinib, mainly in the CD10− neutrophil subset. (h) Arg-1 activity was determined at 48 h before and after ruxolitinib addition in neutrophilsAI. A significant decrease in Arg-1 activity was observed in the cells treated with ruxolitinib. (i) mRNA expression of Arg-1 was detected by RT-PCR in neutrophilsAI at 48 h before and after ruxolitinib addition. A significant decrease was observed in the mRNA expression of Arg-1 in the cells treated with ruxolitinib. (j) mRNA expression of STAT3 was detected by RT-PCR in neutrophils at 48 h before and after ruxolitinib addition. The expression of STAT3 gene in CD10− neutrophil subpopulation significantly decreased. Each experiment was repeated 3 times. ✶P < 0.05, ✶✶P < 0.01, ✶✶✶P < 0.001, ✶✶✶✶P < 0.0001, ns: P > 0.05. Ctrl: Neutrophils before induction, neutrophilsAI: Neutrophils after induction, WB: Western blot, CFSE: Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester, CD10− neutrophils: CD45+CD14−CD33+HLA-DR−CD10− cells, CD10+ neutrophils: CD45+CD14−CD33+HLA-DR−CD10+ cells.

Ruxolitinib is a pan-JAK inhibitor that strongly inhibits the JAK-STAT pathway.[18] However, the functional analysis of ruxolitinib and MDSCs has never been reported. In this study, we attempted to alter the immunosuppressive function of CD10− neutrophil subpopulation with ruxolitinib. As expected, ruxolitinib addition almost completely abolished the ability of CD10− neutrophils to suppress T-cell proliferation [Figure 5c1-c3] and prevented T-cell apoptosis [Figure 5d1-d3] in both systems (neutrophils/CD3+T cells, 2:1; at 48 h). Western blot also showed that ruxolitinib inhibited the expression of STAT3 and p-STAT3 proteins [Figure 5e1 and e2]. STAT3 suppression decreased the expression and activity of Arg-1. Compared with that in induced cells without ruxolitinib, ruxolitinib inhibition of induced neutrophils at 48 h significantly reduced the extracellular [Figure 5f] and intracellular [Figure 5g] expression of Arg-1. Moreover, we confirmed through a flow cytometry gating strategy that the decrease in Arg-1 expression after ruxolitinib addition was mainly observed in the CD10− neutrophil subset, but not in CD10+ neutrophils, and returned to normal levels [Figure 5g]. Consistent with these observations, we detected a significant decrease in Arg-1 activity [Figure 5h] and mRNA expression [Figure 5i] in the cells treated with ruxolitinib, compared with neutrophilsAI without ruxolitinib. Similarly, after adding ruxolitinib, the expression of STAT3 gene in CD10− neutrophil subpopulation significantly decreased [Figure 5j]. These data suggested that STAT3 might regulate the Arg-1 expression of neutrophils in an environment with high concentrations of cytokines.

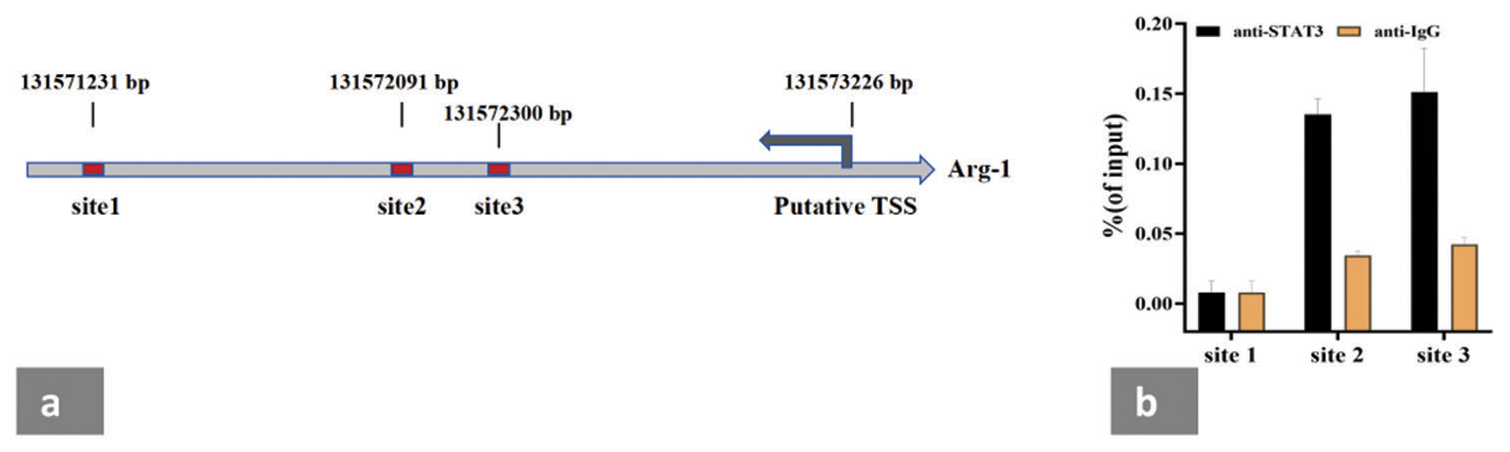

Mechanism of STAT3 effect on Arg-1

STAT3 binds to the promoter region of Arg-1 and increases the expression and activity of Arg-1 in the MDSCs of head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma.[19] To further explore the mechanisms underlying the cytokine-induced expansion and activation of the CD10− neutrophil subpopulation, we used the JASPAR tool to analyze the promoter elements of human Arg-1 to predict STAT3 binding sites and applied the ChIP assay to detect the promoter sequences of the top three Arg-1 scores on the JASPAR system. JASPAR bioinformatics analysis predicted the putative TSS 131573226 kb upstream of Arg-1 [Figure 6a]. In the ChIP assay, an antibody against p-STAT3 (AB267373, Abcam) was used to assess whether p-STAT3 is recruited to the Arg-1 promoter region. ChIP results demonstrated that p-STAT3 was significantly enriched in the region upstream of the Arg-1 promoter, suggesting the existence of two important potential binding sites [Figure 6b].

- STAT3 binds to the promoter region of Arg-1 in the neutrophils rich in CD10− neutrophils induced by cytokines in vitro. (a) Promoter sequence of Arg-1 with scored in the top 3 on the JASPAR system was used for a ChIP assay. (b) p-STAT3 and Arg-1 were enriched in the promoter regions corresponding to site 2 and site 3. TSS: Transcription start site. The experiment was repeated 3 times.

DISCUSSION

Researchers have attempted to identify unique MDSC markers, but the newly identified subpopulations are rarely tested for suppressive functions. Although MDSCs have been preliminarily investigated in hematological diseases,[10,20,21] the function of MDSCs in B-NHL has not been fully explained. CD10 plays an critical role in the differentiation, development, and anti-inflammatory activity of B cells.[22] However, no reports are available on whether the changes in the surface expression level of CD10 on neutrophils in patients with B-NHL indicate a functional shift, such as translation to MDSC-like morphological and functional characteristics.

We observed significant elevations in the frequency and absolute cell counts of CD10− neutrophils in patients with B-NHL at different states, indicating that high levels of CD10− neutrophils may promote disease progression. MDSCs can mediate an increase in T-reg cells by releasing Arg-1, IL-6, and IL-10, leading to an increase in the secretion of immunosuppressive factors by T-reg cells; they can also inhibit T-cell activation and proliferation.[23] Our study was the first to report a positive correlation between the percentage of CD10− neutrophils and IL-6 levels in patients with R/R B-NHL. The circulating numbers of CD10− neutrophils were elevated significantly and positively correlated with T-reg cells but negatively correlated with the absolute number of total T cells. As we hypothesized, the CD10− neutrophils from patients with B-NHL have an inhibitory effect on T lymphocytes and promote the increase in T-reg cells, which are related to the IL-6 level in the tumor microenvironment. A positive correlation was also found between CD10− neutrophils and plasma Arg-1 levels in ND and R/R patients with B-NHL which implied that CD10− neutrophils and Arg-1 may be associated with disease activity in lymphoma, and the immunosuppression of CD10− neutrophils may be mediated by Arg-1. The above features resemble those of traditional granulocytic (G)-MDSCs. We further investigated the relationship between their presence and prognosis of lymphoma. Patients with a high percentage of circulating CD10− neutrophils had short OS and PFS. Moreover, the CD10− neutrophil frequency was an independent risk factor for the OS in patients with B-NHL. These data are consistent with previous studies of MDSCs in solid tumors, myelodysplastic syndromes, acute myeloid leukemia, and myeloma.[20,24-26] We propose elevated circulating CD10− neutrophils as an indicator for predicting poor outcomes in patients with B-NHL.

Under the regulation of the tumor microenvironment, neutrophils produce different phenotypes and functions either to promote or inhibit the occurrence, development, and metastasis of tumors.[27,28] Similarly, G-MDSCs exhibit immature phenotypes and functional heterogeneity.[29] Solito et al. demonstrated that human bone marrow cells can be treated in vitro with defined growth factors to induce a specific cell subpopulation displaying the structure and markers of promyelocytes in MDSCs. When they exert suppressive activity, these promyelocyte-like cells maintain their immature phenotype.[30] Therefore, we speculate that the circulating CD10− neutrophils may also be induced under B-NHL.

In the in vitro induction model, G-MDSCs are mainly differentiated from granulocytes.[31] In our experiments, IL-6, GM-CSF, and G-CSF could all induce the expansion of CD10− neutrophil phenotype cells from the neutrophils extracted from healthy human peripheral blood in vitro, exhibiting typical immature cell morphology. The combination of IL-6 and GM-CSF was the most effective. We observed that the neutrophil population rich in CD10− neutrophils induced by cytokines inhibited the proliferation of autologous T cells and promoted their apoptosis. The abnormal background of high concentrations of cytokines resulted in the significant accumulation of immature granulocytes, and this group of cells has an immunosuppressive function. We observed that the neutrophil population enriched with CD10− neutrophils exhibited higher expression and activity of Arg-1 compared with the unstimulated neutrophils. We further confirmed that the increased expression of Arg-1 protein in the neutrophils rich in CD10− neutrophils was dominated by the CD10− neutrophil subset rather than the CD10+ neutrophils. To establish a possible relationship between Arg-1 and the immunosuppressive function of CD10− neutrophils, we used an Arg-1 inhibitor. The neutrophil population rich in CD10− neutrophils treated with Arg-1 inhibitor abrogated the suppressive function of the CD10− neutrophils and simultaneously reduced the apoptosis of T cells. The neutrophil population rich in CD10− neutrophils and induced by cytokines showed high levels of STAT3 and p-STAT3, which were correlated with Arg-1 expression and activity. Ruxolitinib abrogated the suppressive function of the CD10− neutrophils and simultaneously reduced the expression of STAT3 and p-STAT3 proteins. The inhibition of STAT3 signaling also led to a decrease in Arg-1 expression and activity. ChIP assay confirmed that the Arg-1 in CD10− neutrophils is a downstream target of activated STAT3. These data are consistent with the results of Vasquez-Dunddel et al.[19] The current work is the first to report that active STAT3/Arg-1 signaling is instrumental for CD10− neutrophil-mediated T-cell suppression in vitro.

The CD10− neutrophils described in this study are distinct from fully differentiated or activated granulocytes. Further investigation is required to determine whether CD10− neutrophils represent a stage of the differentiation of granulocytes, possibly ending or being sustained according to local signals coming from the microenvironment where the immature cells migrate.

SUMMARY

CD10− neutrophils circulating in patients with B-NHL might represent a new type of G-MDSCs. Our findings encourage the use of CD10− neutrophil-targeting strategies, such as the JAK-STAT pathway or arginase inhibitor, as adjuvants to conventional chemoimmunotherapy for B-NHL. The results offer a novel explanation for the mechanism of immune escape and resistance to immunotherapy in patients with B-NHL. CD10− neutrophils are a promising cell population that can be used in tolerance therapy and to promote the development of new therapies for autoimmune diseases and transplant rejection.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ABBREVIATIONS

MDSCs: Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

CD10- neutrophils: CD45+CD33+CD14-CD10-HLA-DR-/low neutrophils

CD: Cluster of Differentiation

Arg-1: Arginase-1

Annexin V-PI: Annexin V-Propidium Iodide

HLA-DR: Human Leukocyte Antigen-DR

CHIP: Chromatin immunoprecipitation

WB: Western blotting

B-NHL: B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

G-MDSCs: Granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells

G-CSF: Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

GM-CSF: Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α

IL: Interleukin

IFN: Interferon

JAK: Janus kinase

ND: Newly diagnosed

CR/PR: Complete remission and partial remission

OS: Overall survival

PFS: Progression-free survival

R/R: Relapsed/refractory

STAT: Signal transducer and activator of transcription

p-STAT1: Phospho-STAT1

p-STAT3: Phospho-STAT3

p-STAT5: Phospho-STAT5

NeutrophilsAI: Neutrophils after induction

Ctrl: Control

Arg-1In: Arg-1 inhibitor

CD10+ neutrophils: CD45+CD33+CD14-CD10+HLA-DR-/low neutrophils

ECL: Electrochemiluminescent

TSS: Transcription Start Site

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

ZMZ: Designed the experiment; MX and HPW: Performed all the experiments; JZ: Wrote the manuscript; WQZ, YYD and JJG: Analyzed the data; MX, XL, JLZ and XYJ: Collected the clinical specimens. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. MX and JZ contributed equally to this work.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the ethics review board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (Approval Number: 2023–091) and Jining No.1 People’s Hospital (Approval Number: KYLL-2023 11–184). Informed consent was obtained from each participant and/or their legal guardian.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

EDITORIAL/PEER REVIEW

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through an automatic online system.

FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Number: 82370225) and Key R&D Program of Jining (Number: 2023YXNS096).

References

- Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as immunosuppressive regulators and therapeutic targets in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:362.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12150.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MDSC: Markers, development, states, and unaddressed complexity. Immunity. 2021;54:875-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transcriptional regulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;98:913-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: An emerging target for anticancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:184.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in hematologic diseases: Promising biomarkers and treatment targets. Hemasphere. 2019;3:e168.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The research progress and clinical application of human CD10 molecule. Int J Immunol. 2014;37:363-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expansion and activation of granulocytic, myeloid-derived suppressor cells in childhood precursor B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Leukoc Biol. 2017;102:449-58.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mature CD10+and immature CD10-neutrophils present in G-CSF-treated donors display opposite effects on T cells. Blood. 2017;129:1343-56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CD14-CD10-CD45+HLA-DR-SSC+ neutrophils may be granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell-like cells and relate to disease progression in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma patients. Immunol Cell Biol. 2024;102:256-68.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Association for Clinical Oncologists, Medical Oncology Branch of Chinese International Exchange and Promotion Association for Medical and Healthcare. Clinical practice guideline for lympoma in China (2021 Edition) Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2021;43:707-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neutrophil plasticity in the tumor microenvironment. Blood. 2019;133:2159-67.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How neutrophils shape adaptive immune responses. Front Immunol. 2015;6:471.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myeloid cell-derived arginase in cancer immune response. Front Immunol. 2020;11:938.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targeting STAT3 in cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:145.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic targeting of JAKs: from hematology to rheumatology and from the first to the second generation of JAK inhibitors. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2020;31(Suppl 1):105-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STAT3 regulates arginase-I in myeloid-derived suppressor cells from cancer patients. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1580-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Circulating monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells are elevated and associated with poor prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020:7363084.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical impact of the immunome in lymphoid malignancies: The role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Front Oncol. 2015;5:104.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The density of CD10 corresponds to commitment and progression in the human B lymphoid lineage. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12954.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIF-1aregulates function and differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2439-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as a therapeutic target for cancer. Cells. 2020;9:561.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Increased myeloid-derived suppressor cells in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes suppress CD8+T lymphocyte function through the STAT3-ARG1 pathway. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;62:218-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Increased monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in whole blood predict poor prognosis in patients with plasma cell myeloma. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4717.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CXCL5 as Regulator of neutrophil function in cutaneous melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:186-94.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neutrophil degranulation, plasticity, and cancer metastasis. Trends Immunol. 2019;40:228-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The diversity of circulating neutrophils in cancer. Immunobiology. 2017;222:82-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A human promyelocytic-like population is responsible for the immune suppression mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Blood. 2011;118:2254-65.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myeloid-derived suppressor cells coming of age. Nat Immunol. 2018;19:108-19.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]