Translate this page into:

Bone marrow elements in cerebrospinal fluid: Review of literature with a case study

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Presence of bone marrow elements in cerebrospinal fluid is rare. Journal publications on this topic are few and majority of them were written over a decade ago mostly as case reports in young children or the elderly. The increased cellularity and presence of myeloid precursors can be a pitfall and may be misdiagnosed as leukemia or lymphoma or central nervous system infection, when the specimen is actually not representative. With the intention to create awareness of potential pitfalls and avoid erroneous diagnoses, as well as adding on to the current photo archive of bone marrow elements in CSF, we present a recent case of bone marrow contaminants in the CSF of a 16-year-old girl.

Keywords

Bone marrow

cerebrospinal fluid

contaminant

pitfall

INTRODUCTION

Bone marrow elements can be seen on rare occasions as contaminants in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The increased cellularity and presence of myeloid precursors may result in an erroneous cytological diagnosis of central nervous system (CNS) infection or even lymphoma or leukemia. Treatment following the misdiagnoses would be unnecessary and possibly harmful for the patient. Due to its uncommon occurrence, majority of the literature on bone marrow elements found in CSF were written over a decade ago, mostly reported in young children or the elderly. Even though some textbooks do mention bone marrow elements in CSF, there are limited good photographic illustrations. With the intention to create awareness of potential pitfalls and avoid erroneous diagnoses, as well as adding on to the current photo archive of bone marrow elements in CSF, we present a recent case of bone marrow contaminants in the CSF of a 16-year-old girl.

CASE REPORT

A 16-year-old female patient presented with a sudden onset headache, photophobia, left lower leg weakness and jerking movements of upper and lower limbs. Meningitis was queried clinically. She had no past medical history and both chest X-ray and computed topography scan were normal. A lumbar puncture (LP) was performed and CSF for cytology was collected into two tubes. The first tube had 0.5 ml of clear colorless fluid and the second tube had 0.3 ml of slightly blood-tinged fluid. Two cytospin slides were prepared from each of the tubes and stained with both Papanicolaou stain and a Romanowsky-based stain for examination.

Cytological findings

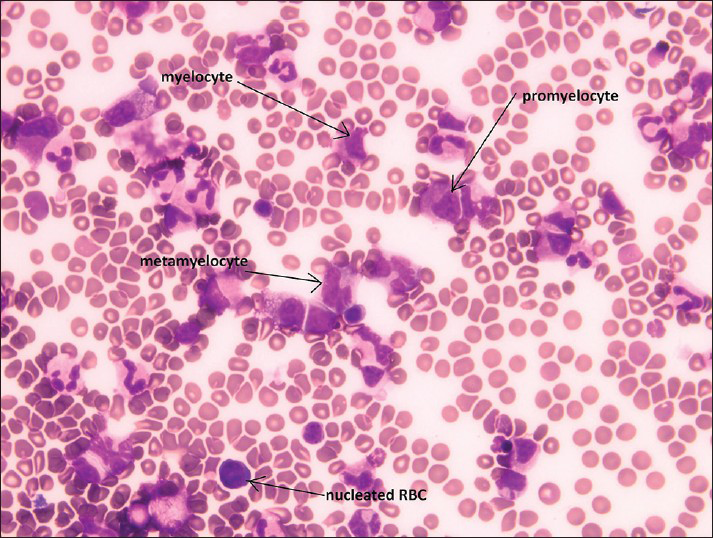

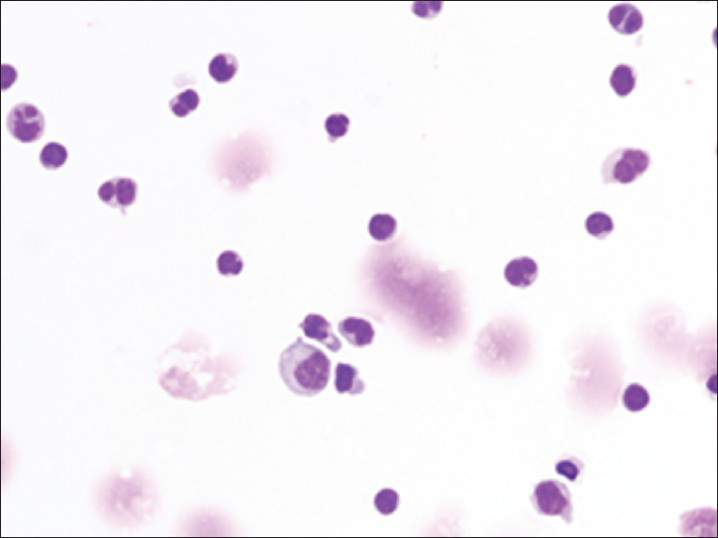

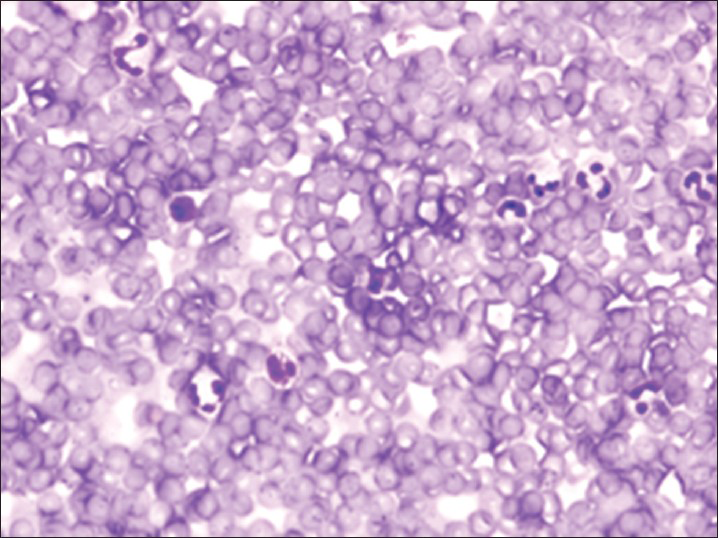

Both specimens show similar findings, with the second specimen more cellular than the first specimen. The specimen contains myeloid and erythroid precursors at various stages of maturation together with occasional lymphocytes and monocytes [Figure 1]. Myeloid precursors such as promyelocyte, myelocyte and metamyelocyte are seen in Figure 1. No megakaryocytes are seen. On review by the cytopathologist, the diagnosis of bone marrow elements as contaminants in the CSF was suggested.

- Cerebrospinal fluid containing bone marrow elements including promyelocyte, myelocyte, metamyelocyte and nucleated red blood cells

The CSF was reported as non-diagnostic as it contains predominantly bone marrow elements, which are indicative of sampling error and as such, an unsuitable specimen for accurate assessment. Correlation with microbiology and hematology studies was recommended. Subsequent microbiology studies showed decreased leucocyte count (<1 × 106/l) and no growth in blood culture. Hematology studies were within normal limits despite the slight increase in neutrophils and a slight decrease in lymphocytes, red blood cell count and hemoglobin and hematocrit value. Patient was discharged subsequently.

Most CSF specimens are obtained from the subarachnoid space by LP.[1] The cutting Quincke needle remains the most commonly used needle for LP despite the introduction of the non-cutting atraumatic needle that decreases the incidences of post LP headache.[234] Wright et al.,[1] details the stepwise procedure for CSF collection, from the preferable lateral recumbent position that the patient assumes, the use of the L4 vertebra to locate the L3-L4 or L4-L5 intervertebral spaces,[5] insertion of an LP needle, indication of successful needle entry into the subarachnoid space and assessment of CSF flow. Needle repositioning is indicated if the attempt is unsuccessful such as when the needle strikes bone or when the patient experiences a shooting leg pain, which indicates overly lateral needle placement touching the lateral nerve root. The needle is withdrawn slightly, re-angled and advanced gently until a gap is found.[1] Multiple attempts at different sites during the procedure are discouraged, but when needed, the use of muscle relaxants such as a low dose benzodiazepine may aid in minimizing risk of muscle spasms.[1] CSF collected from a traumatic LP will be tinged with blood, which should disappear with serial collections.[1]

Normal CSF, collected from an adult who does not have a neurologic disorder, seizures or undergoing myelography, has low cellularity containing less than 5 cells/mm3.[56] These cells consist of small numbers of mature lymphocytes, monocytes and occasional neutrophils. Other non-neoplastic cellular elements that may be seen in CSF include squamous cells, chondrocytes, meningothelial cells, brain fragments, choroidal cells, ependymal cells and hemopoietic elements from bone marrow or peripheral blood.[56] Germinal matrix cells and notochord remnants may also be seen in newborns.[6] Most of the above mentioned cells are easily recognizable. Bone marrow and peripheral blood elements however require discernment when deciding if a specimen is representative of the area sampled. Bone marrow contamination in particular is rare and may be misinterpreted or overlooked due to inexperience.

The sole cytological diagnostic criterion for bone marrow elements in CSF is the presence of erthyroid precursors, for example a normoblast, together with myeloid precursors.[789] Megakaryocytes may be helpful and have been seen in some cases.[6] When unnoticed, bone marrow elements may become a pitfall for CNS infection such as bacterial or viral meningitis or hematological malignancies including acute leukemia or lymphoma.[10]

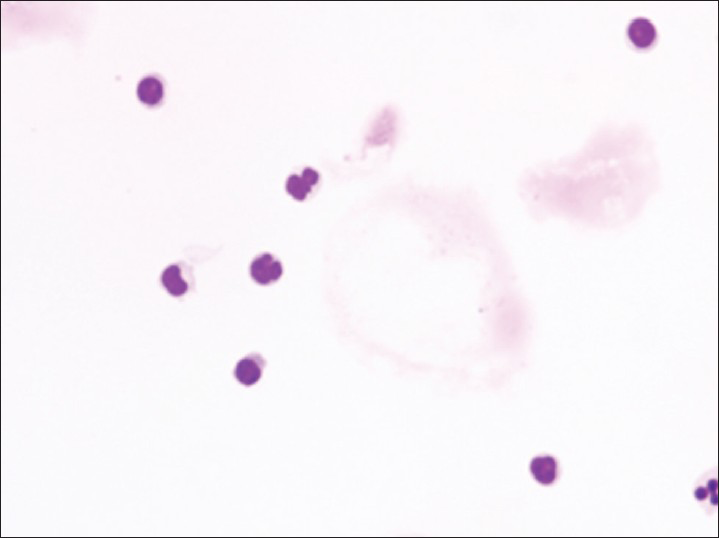

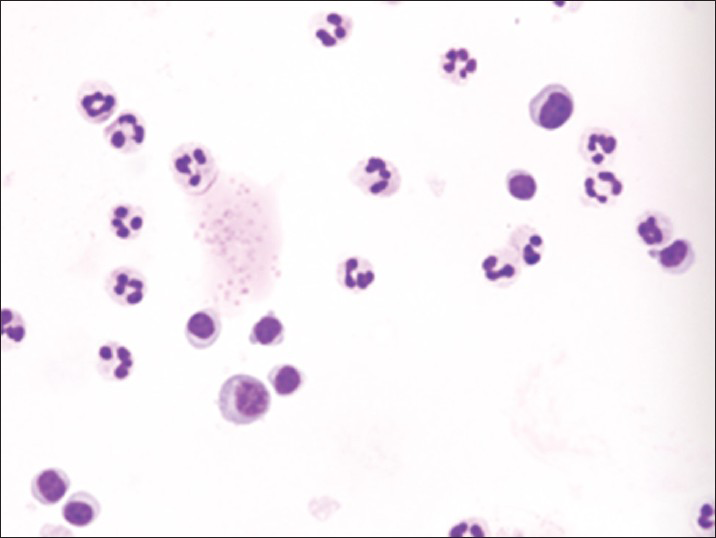

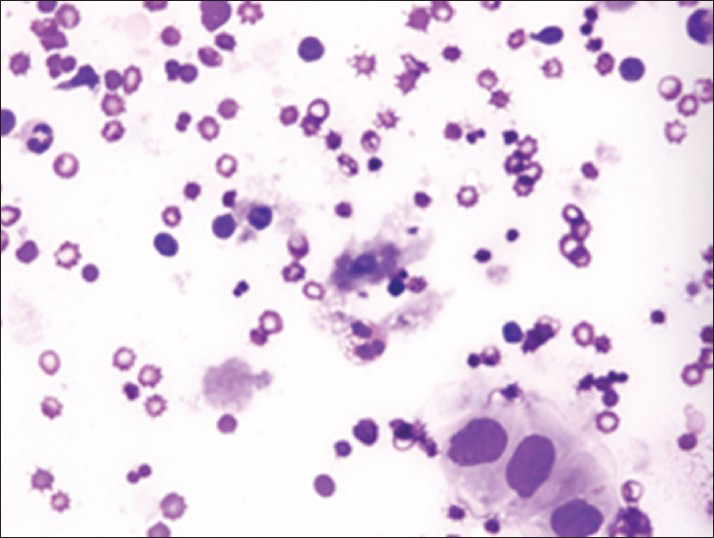

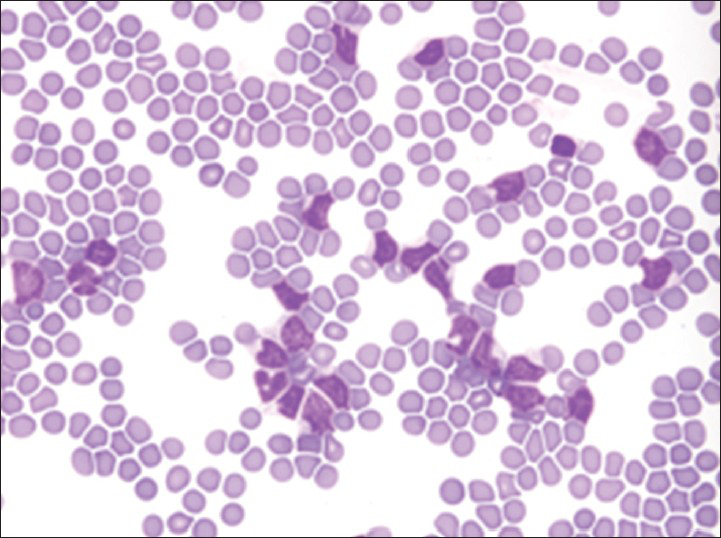

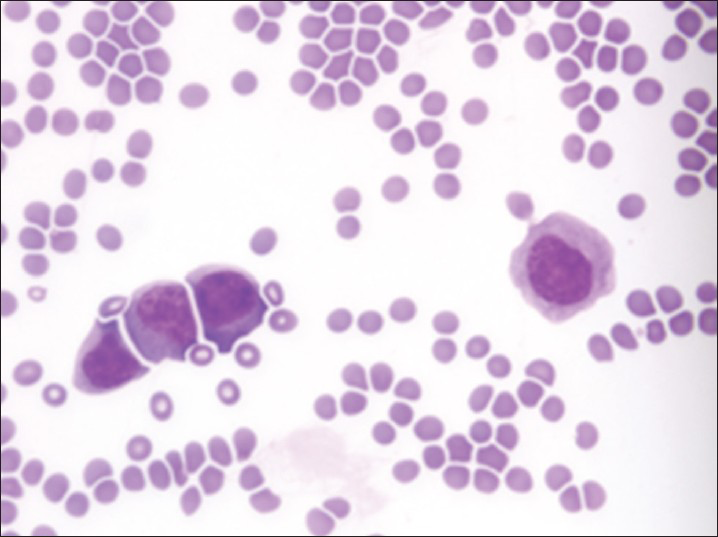

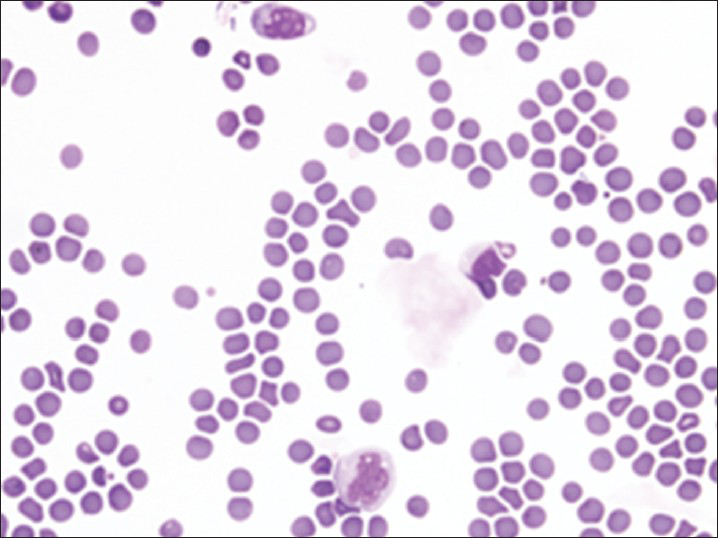

Increased cellularity of CSF due to bone marrow elements presents an abnormal CSF picture and has many differential diagnoses. It is important to identify these cases and not over diagnose them as lymphomas or leukemia. Bone marrow elements in CSF should not be misdiagnosed as inflammatory infection caused by CNS infection to prevent the unnecessary antibiotic administration. A cytological picture of predominantly polymorphonuclear leukocytes may indicate non-specific mixed inflammation [Figure 2], bacterial meningitis [Figure 3], cerebral abscess and empyema, CNS hemorrhage and infarction or occasionally the early stages of viral and fungal infection.[58] Immune response caused by malignant processes may present a similar picture [Figure 4].[11] Other infective differential diagnoses include mycobacterial tuberculosis and viral meningoencephalitis in which the CSF contains predominantly lymphocytes and monocytes [Figure 5].[5] The presence of myeloid and lymphoid precursors may suggest CNS involvement by acute leukemia [Figure 6], lymphoma [Figure 7] or contamination by peripheral blood with abnormal blasts [Figure 8].[11] Increased numbers of red blood cells may also result in misdiagnosis of a traumatic tap [Figure 9].

- Mixed inflammation showing small numbers of lymphocytes and neutrophils

- Neutrophilia together with small numbers of normal and activated lymphocytes

- Malignant cells of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma surrounded by polymorphous inflammation

- Viral meningitis showing normal and activated lymphocytes with and scattered macrophages

- Acute lymphoblastic leukemia containing numerous lymphoblasts

- Abnormal blasts in B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma

- Contaminant peripheral blood containing abnormal blasts

- Traumatic tap showing numerous red blood cells with scattered neutrophils and lymphocytes consistent with peripheral blood

Bone marrow-contaminated CSF submitted for hematological review may result in abnormal white cell counts, unusual differential counts and occasional erroneous diagnosis.[9] Therefore, correlation with microbiological, biochemical and cytological results is important for the assessment of CSF. Negative cultures for virus, fungal, tuberculosis and bacteria exclude the possibility of an infection. The lack of malignant cells together with a combination of low total protein (<45 mg/dl), high glucose (above 45 mg/dl) and normal total cell count has a high negative predictive value, eliminating the possibility of a malignant process.[11] The presence of bone marrow elements cytologically highlights the possibility that the abnormal white blood cell population could be benign hemopoietic elements.

The common explanation for having bone marrow elements in a CSF is when the LP needle is pushed too far anteriorly into the marrow cavity of a vertebral body sampling bone marrow elements. The cells adhere to the needle barrel and are subsequently flushed out together with the flow of CSF after the needle is successfully repositioned.[9] McIntyre[12] suggested an alternate situation where the tip of the needle gets embedded in the bone marrow and cells are aspirated into the needle by very high vacuum forces generated when the stylet is withdrawn rapidly. CSF specimen containing bone marrow elements previously reported were most often from elderly or infant and young patients whereby decreased bone density resulting from geriatric conditions, metastatic diseases or developing bones may have allowed easier penetration of vertebral bone by the LP needle.[78910]

It is rare to see bone marrow elements in CSF because the vertebral body is avoided during the LP to reduce patient discomfort and ensure good CSF collection flow.[1] Experienced neurologists and imaging aids play a great role in improving accuracy and efficiency of CSF collection.[113] Improved knowledge of nutrition and ideal dietary habits aid in prevention and treatment of bone conditions such as osteoporosis, reducing the likelihood of needle penetration of the vertebral body. There may also be cases that have been overlooked or misinterpreted by cytotechnologists and pathologists.

SUMMARY

In summary, there are three take home messages from this case. Firstly, bone marrow elements should always be considered when assessing cellular CSF containing erythroid precursors presenting together with myeloid precursors. Secondly, a polymorphous picture should not be automatically assumed to be a proliferative lymphoid disease or inflammatory changes due to infections; instead it should initiate a search for erythroid precursors and metastatic malignant cells. Lastly, correlations between cytological findings, hematology, biochemistry and microbiology results are important as these aid to avoid pitfalls like immune response in a CNS infection or leukemia and lymphoma.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Dr. Felicity Frost (PathWest Laboratory Medicine, QEII Medical centre) for her contribution in the diagnosis of the case.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that they qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author. Each author has participated sufficiently in the study and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article. Each author acknowledges that this final version has been read and approved by them.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is case report without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) (or its equivalent). Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2013/10/1/20/119009

REFERENCES

- Cerebrospinal fluid and lumbar puncture: A practical review. 2012. J Neurol. 259:1530-45. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22278331 http://www.springerlink3.metapress.com/content/48867658032h4480/resourc-secured/?target=fulltext.pdf and sid=chzgbecpyywxrtyzvjfh5ohi and sh=www.springerlink.com

- [Google Scholar]

- Randomised controlled trial of atraumatic versus standard needles for diagnostic lumbar puncture. 2000. BMJ. 321:986-90. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/content/321/7267/986?view=long and pmid=11039963

- [Google Scholar]

- Cost comparison between the atraumatic and cutting lumbar puncture needles. 2012. Neurology. 78:109-13. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22205758 http://www.neurology.org/content/78/2/109.long

- [Google Scholar]

- Atraumatic lumbar puncture needles: After all these years, are we still missing the point? 2009. Neurologist. 15:17-20. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19131853

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytopathology of the Central Nervous System. London: Edward Arnold Publishers; 1994. p. :21-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytology: diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates. (3rd ed). Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2009. p. :171-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contamination of cerebrospinal fluid with bone-marrow cells during lumbar puncture [letter to the editor] 1983. N Engl J Med. 309:434-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=6877306[uid]

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerebral spinal fluid pleocytosis with bone marrow contamination. 1984. J Pediatr. 104:254-6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6694022

- [Google Scholar]

- Contamination of cerebrospinal fluid by vertebral bone-marrow cells during lumbar puncture. 1983. N Engl J Med. 308:697-700. Available form: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6828109 http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM198303243081206

- [Google Scholar]

- Hematopoietic elements in cerebrospinal fluid in children. 1991. Am J Clin Pathol. 95:532-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2014779

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerebrospinal fluid cytological and biochemical characteristics in the presence of CNS neoplasia. 2007. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 65:802-9. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext and pid=S0004-282×2007000500014 and lng=en and nrm=iso and tlng=en http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext and pid=S0004-282×2007000500014 and lng=en and nrm=iso and tlng=en

- [Google Scholar]

- Contamination of cerebrospinal fluid by vertebral bone-marrow cells during lumbar puncture [letter to the editor] 1983. N Engl J Med. 309:434-5. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJM198308183090719

- [Google Scholar]

- The use of ultrasound to identify pertinent landmarks for lumbar puncture. 2007. Am J Emerg Med. 25:331-4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17349909

- [Google Scholar]