Translate this page into:

Cytologic diagnosis of adrenal oncocytic pheochromocytoma in a lung cancer patient: Report of a case and review of the literature

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Adrenal oncocytic pheochromocytoma is an extremely rare type of pheochromocytoma. To the best of our knowledge, we present the first cytological diagnosis of this variant via fine-needle aspiration in an 81-year-old male patient who was found to have an adrenal mass while undergoing workup of the recently diagnosed lung adenocarcinoma. We describe the cytomorphologic findings in our case and provide a review of the reported cases of adrenal oncocytic pheochromocytoma – all of which appear to be benign, nonfunctional, occur in adults, and have similar morphologic features. The pathologist should be aware of this uncommon diagnostic entity and its potential diagnostic pitfalls.

Keywords

Adrenal

cytology

fine-needle aspiration

oncocytic

pheochromocytoma

INTRODUCTION

Adrenal pheochromocytoma, oncocytic type, is a rare variant of pheochromocytoma, only four cases of which have been described in the literature.[1234] In all of these cases, the diagnosis was made on surgical specimens of the resected tumors. Here, we report the first case of a cytological diagnosis of oncocytic pheochromocytoma on fine-needle aspirate specimens of an adrenal nodule that was clinically suspected to be a metastasis from lung adenocarcinoma.

CASE REPORT

An 81-year-old man with a past medical history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia presented for a follow-up of a newly diagnosed lung adenocarcinoma. His hypertension was controlled with amlodipine, atenolol, enalapril, and hydralazine. However, he denied any new-onset symptoms such as headache, diaphoresis, flushing, and palpitations. His blood pressure was 124/64 and heart rate 76. Three weeks prior to the current procedure, the patient was diagnosed with lung adenocarcinoma (3 cm) in the right upper lobe via computed tomography (CT)-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and core biopsy.

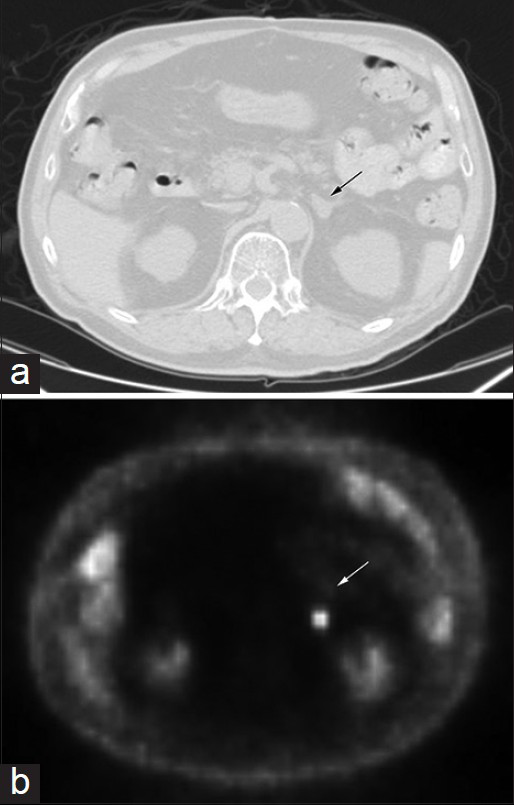

To determine the presence of metastases, a positron emission tomography (PET) scan was performed. The PET-CT scan detected 18-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose-avid areas in the aforementioned lung nodule (standardized uptake value [SUV] 2.5), right inferior hilar region (SUV 2.3), and a 1.5 cm left adrenal nodule (SUV 9.8). The adrenal mass was suspicious for metastasis [Figure 1].

- Images of computed tomography (a) and corresponding positron emission tomography (b) scan of the patient's abdomen showing the adrenal mass (arrow), 1.5 cm in diameter and standardized uptake value of 9.8

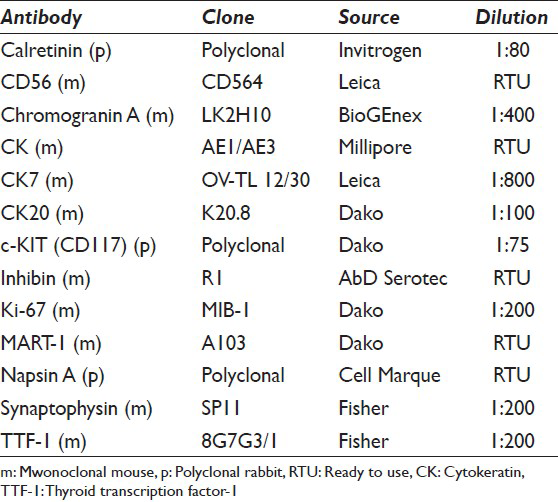

Consequently, CT-guided FNA of the left adrenal mass was performed. Both air-dried and alcohol-fixed smears were prepared from two passes, and the remaining material was rinsed into CytoRich Red fixative for cell block preparation. On-site evaluation of the air-dried Diff-Quik-stained smears performed by the pathologist confirmed the adequacy of the samples. The alcohol-fixed smears were stained with Papanicolaou stain in the laboratory. The material for cell block preparation was routinely processed, and the slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Immunocytochemical stains were performed on the cell block preparation slides in an automated immunostainer in the presence of appropriate positive and negative controls. Table 1 shows the information regarding the source and dilution of the antibodies used in the case.

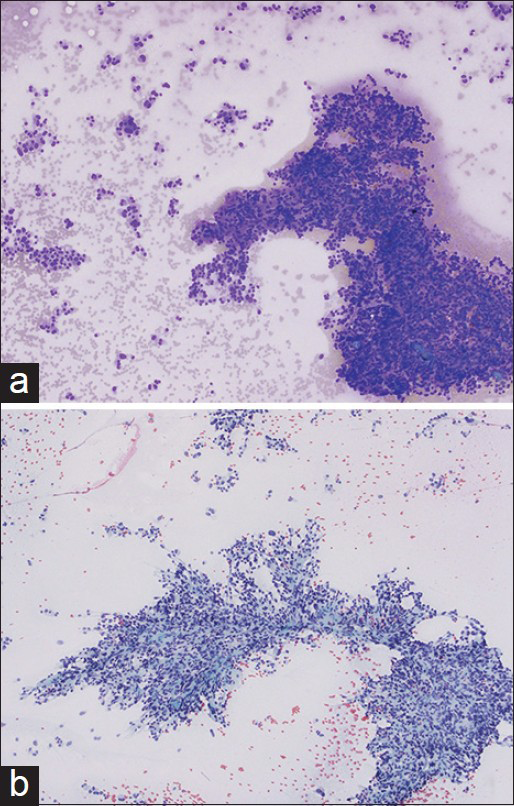

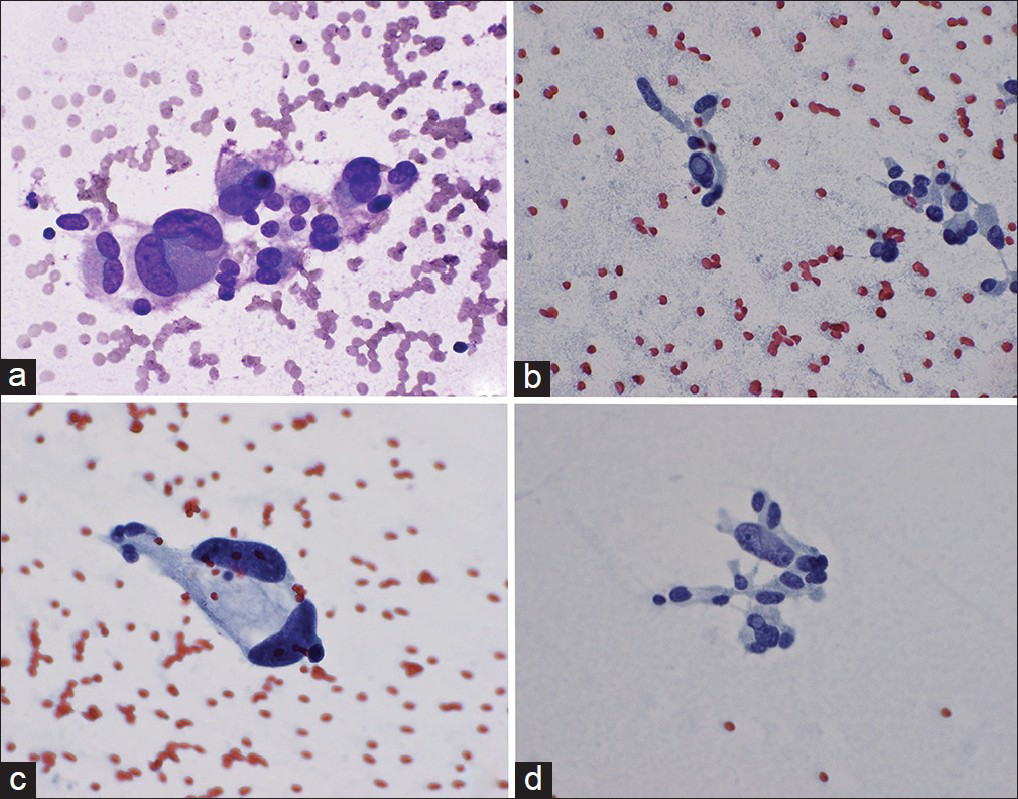

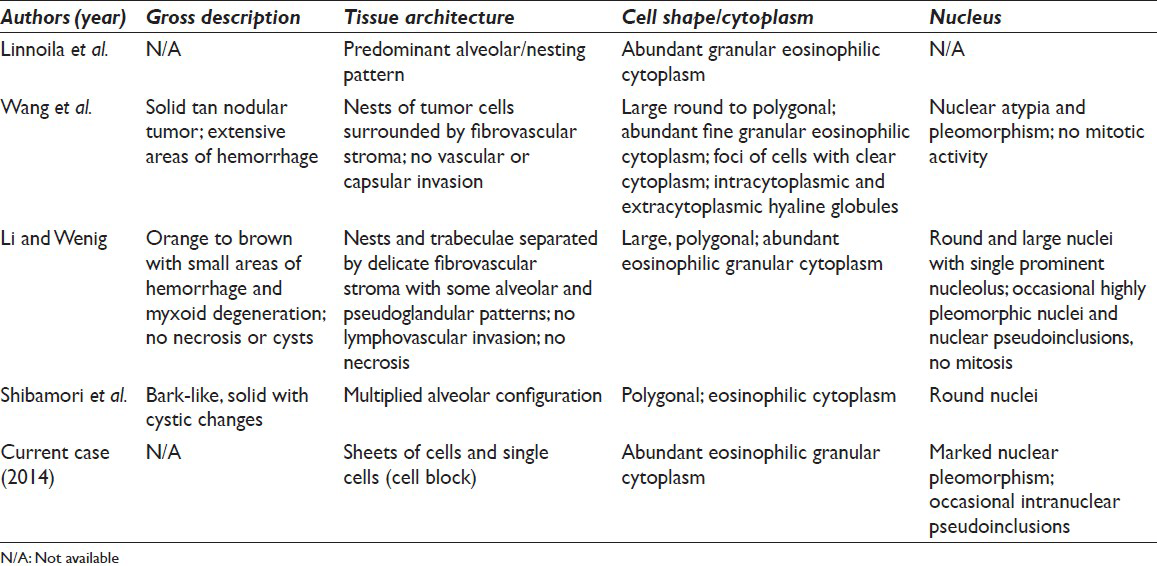

Evaluation of the aspirate smears and cell block preparations showed numerous loosely cohesive sheets and singly scattered tumor cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm [Figures 2-4]. These cells exhibited marked nuclear pleomorphism, indistinct cell borders, and occasional intranuclear pseudoinclusions [Figures 2-4]. Occasional binucleated cells and cells with bizarre nuclei were also identified [Figure 3]. These cytologic features were noted to be distinct from the adenocarcinoma of the lung found in the patient upon the concurrent review of the previous FNA and core biopsy specimens of the lung nodule.

- Low magnification of fine-needle aspiration smears, showing loosely cohesive sheets and single cells of oncocytic pheochromocytoma with Diff-Quik (a) and Papanicolaou (b) stains, (×100)

- High magnification of tumor cells showing markedly pleomorphic and bizarre nuclei. (a) and (c) show binucleation and (b) and (d) show intranuclear pseudoinclusions, (×600)

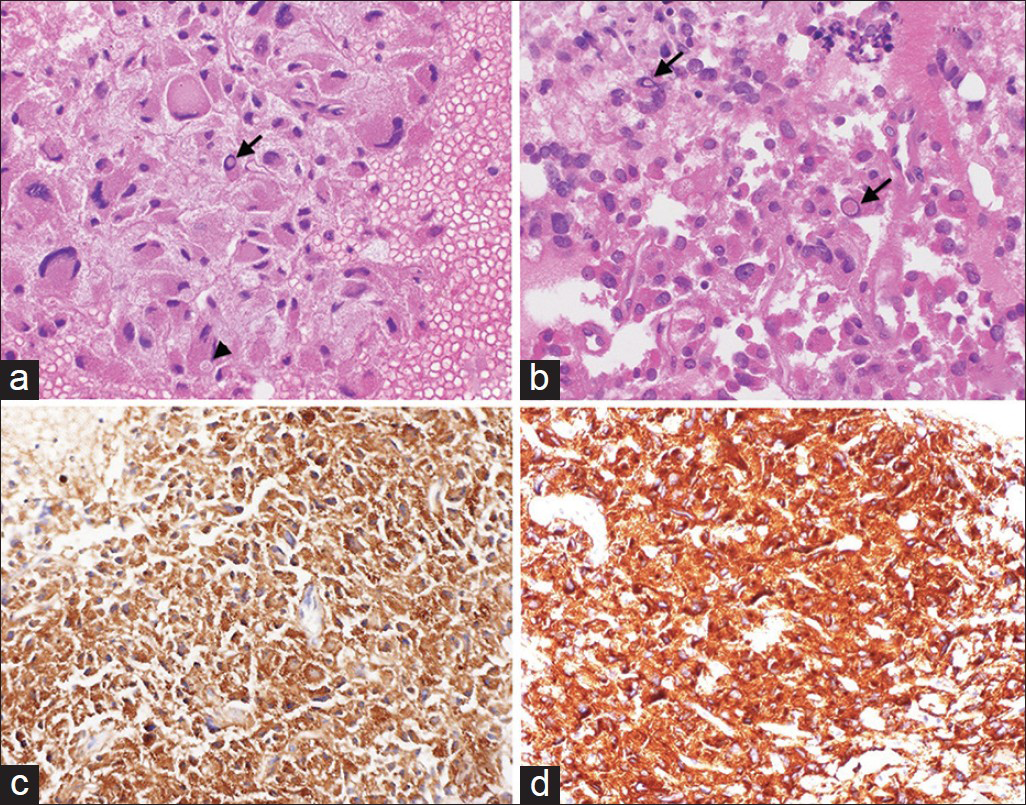

- (a and b) Cell block preparation of the aspirate stained with H and E showing oncocytic tumor cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, nuclear pleomorphism, cytoplasmic inclusions (arrowhead), and intranuclear pseudoinclusions (arrows). Tumor cells show strong positivity to chromogranin (c) and synaptophysin (d), (×400)

Immunostains for lung markers – cytokeratin-7 (CK7), thyroid transcription factor-1, and napsin A – were negative, showing that the adrenal neoplasm did not derive from the lung adenocarcinoma. The tumor cells were positive for neuroendocrine markers, CD56, chromogranin [Figure 4c], and synaptophysin [Figure 4d], consistent with the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. To show that the tumor cells did not originate from an adrenal cortical lesion, immunohistochemical stains for calretinin, MART-1, and inhibin A were performed and indeed, found to be negative. Moreover, the tumor cells did not react with CK, CK20, and c-KIT. Ki-67 showed <2% proliferative activity in the tumor cells.

Overall, the morphological features and immunohistochemical phenotype of the tumor were consistent with the diagnosis of adrenal pheochromocytoma, oncocytic type.

DISCUSSION

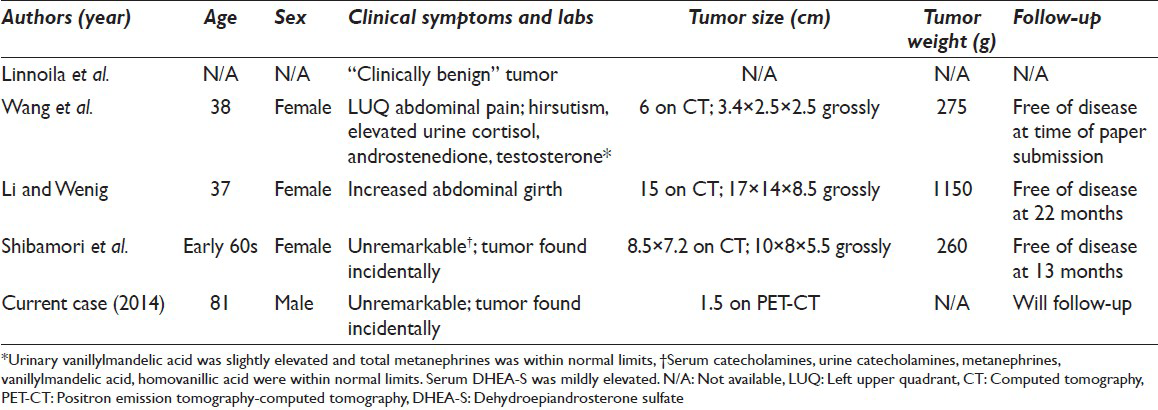

Oncocytic neoplasms have been described in several organs and well-characterized in many of the neuroendocrine organs. Oncocytic tumors of the adrenal gland are very rare, however. Approximately, 150 oncocytic adrenal cortical tumors have been reported.[5] Oncocytic tumors of the adrenal medulla are far rarer still with only five reported cases, four which were pheochromocytomas and one adrenal medullary oncocytoma.[12346] The oncocytic variants of adrenal pheochromocytomas are so rare that they were not mentioned in the most recent reviews of adrenal oncocytic neoplasms.[578] Linnoila et al. first reported the oncocytic type in their study of 120 pheochromocytomas to characterize benign and malignant features.[1] After this initial histopathological report, the three subsequent case reports characterized the clinical aspects of the tumor as well as the histological features.[234] Our case represents the fifth report of the adrenal pheochromocytoma, oncocytic type, and the first report of a cytological diagnosis via FNA. These tumors were shown to be oncocytic by morphology and electron microscopy and shown to be pheochromocytomas by immunohistochemical markers like neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin A and CD56. A review of clinicomorphologic characteristics of these five cases is summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

None of the patients with oncocytic pheochromocytomas presented with symptoms of excess epinephrine such as new onset episodic hypertension, headache, flushing, diaphoresis, and palpitations. In two cases including this present one, the patients had long-standing hypertension which suggests it was not due to excess catecholamines. The cases that did include the chemical workup of pheochromocytomas did not have a significant increase in catecholamines and their metabolites, consistent with the lack of clinical symptoms. These negative findings suggest that oncocytic pheochromocytomas reported thus far are “silent” and are nonfunctional.

This latter suggestion correlates with the ultrastructural features of oncocytic neoplasms in general. Electron microscopy shows that the oncocytic tumor cells acquire the abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm due to the increased number and size of mitochondria.[23] Mitochondrial proliferation is thought to represent a degenerative process,[9] which may be why most oncocytic neoplasms of the adrenal gland are nonfunctional. Li and Wenig found few membrane-bound dense-core granules in the cells via electron microscopy despite the strong positivity to chromogranin.[3] Furthermore, the high density of mitochondria may explain why the adrenal tumor in this case was so metabolically active with an SUV of 9.8 compared to that of the lung adenocarcinoma (SUV 2.5).

It is hypothesized that increased mitochondrial activity and the state of hypoxia itself may cause increased reactive oxygen species which may, in turn, induce tumorigenic alterations in mitochondrial and nuclear DNA.[5810] Indeed, genetic studies in oncocytic neoplasms of other organs showed mutations in both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA that are related to mitochondrial function.[7]

None of the reported oncocytic pheochromocytomas showed clinical signs of malignancy. The tumor size is generally considered to be helpful in assessing whether pheochromocytomas are benign or malignant. This does not appear to be the case in oncocytic pheochromocytomas. Despite the low proliferative index as assessed by the Ki-67 immunohistochemical stain, the previously reported oncocytic pheochromocytomas were large not because of their aggressive nature and rapid growth but presumably because they escaped detection for a long time until they eventually became big enough to cause a mass effect.[237] Alternatively, they were found incidentally during a work-up of another condition as in our case.

Fine-needle aspiration has been proven to be a safe and valuable modality in the work-up of adrenal lesions. However, it is advisable to exclude pheochromocytoma in patients without cancer history before performing adrenal FNA due to potential complications of precipitating a hypertensive crisis and bleeding.[11] In our case, because the adrenal nodule was clinically suspected to be a metastasis from the lung carcinoma, pheochromocytoma was not suspected in our patient; therefore, measurements of catecholamines and their metabolites were not assessed. No complications occurred during the FNA procedure in our patient, further corroborating the suggestion that the oncocytic pheochromocytoma was nonfunctional.

The differential diagnoses for adrenal oncocytic pheochromocytoma in FNA specimens include adrenal cortical adenoma and carcinoma, oncocytoma of the medulla,[6] extension or metastasis of oncocytic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) or chromophobe RCC, and metastasis from melanoma, lung, and liver primaries, among others. By definition, oncocytic tumors have similar cytological features of abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm with central or eccentric nuclei. Immunohistochemical studies are helpful for distinguishing these tumors. For example, chromogranin A and CD56 are specific for pheochromocytomas, whereas positivity for calretinin, MART-1, and inhibin A would indicate an adrenocortical origin. Synaptophysin can be positive in both pheochromocytomas and adrenal cortical tumors.[12] CKs are thought to be generally negative in oncocytic tumors as in our case.[5] On the other hand, the cases presented by Wang et al. and Li and Wenig showed positive immunohistochemical stains for CKs.[23] This is not totally extraordinary, however since more than a quarter of pheochromocytomas was found to react positively for CK.[13]

CONCLUSION

This represents the first cytologic diagnosis of adrenal oncocytic pheochromocytoma by FNA. Keeping the differential diagnosis for this lesion in mind during the evaluation of adrenal FNA specimens and procuring additional tissue sampling for ancillary studies are crucial for arriving at a correct diagnosis.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE.

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work. ASN drafted the article and prepared the figures and tables. TG conceived of and directed the study as well as prepared the figures. JHK and TG were involved in the diagnosis of the case presented and provided significant suggestions and edits. Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is the case report without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) (or its equivalent).

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Histopathology of benign versus malignant sympathoadrenal paragangliomas: Clinicopathologic study of 120 cases including unusual histologic features. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:1168-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oncocytic pheochromocytoma with cytokeratin reactivity: A case report with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies. Int J Surg Pathol. 1997;5:61-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oncocytic pheochromocytoma of the adrenal gland with preoperative endocrine examination. Int Cancer Conf J. 2013;2:165-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oncocytic lesions of the thyroid, kidney, salivary glands, adrenal cortex, and parathyroid glands. Int J Surg Pathol. 2014;22:33-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The causes of cancer revisited: “Mitochondrial malignancy” and ROS-induced oncogenic transformation – Why mitochondria are targets for cancer therapy. Mol Aspects Med. 2010;31:145-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration of catecholamine-producing adrenal masses: A possibly fatal mistake. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145:113-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- A tissue microarray-based comparative analysis of novel and traditional immunohistochemical markers in the distinction between adrenal cortical lesions and pheochromocytoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:423-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expression of intermediate filaments in neuroendocrine tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990;114:506-10.

- [Google Scholar]