Translate this page into:

Cytology of achylous hematuria: A clue to an underlying uncommon clinical scenario

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

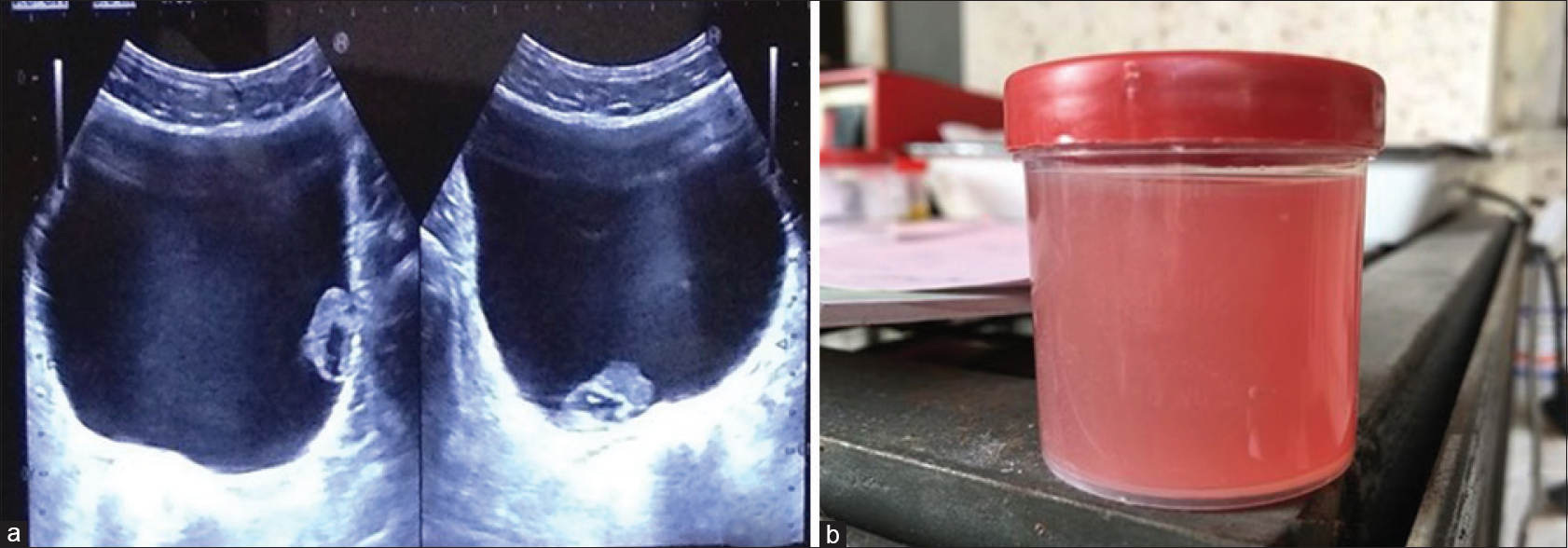

A 26-year-old male presented with chief complaints of on and off painless hematuria, and burning micturition for the past 3 months. The patient also had an episode of fever 1 month back. There was no history of increased frequency of micturition, dysuria, renal or ureteric colic, jaundice, trauma, instrumentation, or passage of milky white urine. Complete blood count and peripheral smear examination were within normal limits at the initial presentation. Ultrasound sonography abdomen showed distended urinary bladder and low-level internal echoes in the lumen with heteroechoic lesion [Figure 2a]. Clinical suspicion of carcinoma of the urinary bladder was raised. Urine cytology showed finding shown in Figure 1.

![(a) Day-1 urine cytology smear showing predominantly lymphoid cells (Giemsa, ×100); (b) Urothelial cells along with lymphoid cells and occasional eosinophil on day 2 urine sample (Pap, ×100); (c and d) These structures on day 2 sample (Giemsa, [c] ×200 and [d] ×400]; (e and f) Day 4 urine cytology showing the structures with urothelial cells and lymphocytes (Pap, [e]×100 and [f]×400).](/content/105/2018/15/1/img/CJ-15-30-g001.png)

- (a) Day-1 urine cytology smear showing predominantly lymphoid cells (Giemsa, ×100); (b) Urothelial cells along with lymphoid cells and occasional eosinophil on day 2 urine sample (Pap, ×100); (c and d) These structures on day 2 sample (Giemsa, [c] ×200 and [d] ×400]; (e and f) Day 4 urine cytology showing the structures with urothelial cells and lymphocytes (Pap, [e]×100 and [f]×400).

- (a) Ultrasonography abdomen showing distended urinary bladder with hetero-echoic lesion in the lumen. (b) Gross image of achylous thin reddish-brown urine sample from the patient presenting with hematuria

Q1: WHAT IS YOUR INTERPRETATION?

-

Urinary filariasis (Wuchereria bancrofti)

-

Schistosoma larvae

-

Strongyloidiasis with underlying bladder malignancy

-

Filariasis with underlying lymphoid malignancy.

ANSWER 1

Option A: Urinary filariasis (W. bancrofti)

Explanation

The urinary sediment smears were stained by Papanicolaou and Giemsa stains. They showed the presence of many reactive lymphoid cells, few eosinophils, and neutrophils along with a predominance of RBCs and few degenerated benign urothelial cells. Also noted were microfilariae of W. bancrofti in the 2nd and 5th day urine samples, confirmed by the presence of a sac-like hyaline sheath, which was present throughout the length, a cephalic space and nuclei, extending from the head and ending abruptly, leaving the tail tip free of nuclei, and the pointed terminal end. No atypical urothelial cells were noted.

Acetone test was done on the 5th day urine sample. Grossly, we had received 15 ml blood mixed fluid. The sample was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 3 min. On addition of few drops of acetone in the centrifuged sample, opacity was not cleared of; suggesting the absence of chyle in urine [Figure 2b]. A repeat hemogram showed the presence of increased absolute eosinophil count (800/μL); however, no parasite was noted on PS examination. The patient was treated with a 21-day course of diethylcarbamazine and was doing well until last follow-up.

ADDITIONAL QUESTION

Q2: What is lesion in urinary bladder?

-

Primary bladder malignancy

-

Metastasis to the urinary bladder

-

Blood clot

-

Nonneoplastic lesion.

ANSWER 2

Option C: Blood clot

Explanation

Ultrasound abdomen revealed a distended urinary bladder and showed low-level internal echoes in the lumen of the bladder with heteroechoic contents which were mobile; hence, a possibility of clots was suggested, but the histological correlation was advised to rule out any underlying malignancy. Urine was sent for cytological evaluation.

Schistosoma larvae (cercariae) are released from snails into water and penetrate human skin exposed to infected water. Eggs are deposited in bladder wall vessels and incite a granulomatous response resulting in polypoid lesions and also causing eosinophilic inflammation, necrosis and ulceration, followed by fibrosis.

Strongyloides stercoralisis a human pathogenic parasitic roundworm causing the disease strongyloidosis. Its commonly called as threadworm. Infection is usually seen in lung & small intestine. Tissue eosinophilia and granulocytic infiltration may cause abscess formation.

DISCUSSION

Filariasis is a major public health problem in tropical countries, especially in the Asian continent. It is a disabling parasitic infection noted worldwide.[1234] The various species of filarial organisms are W. bancrofti, B. malayi, Brugia timori, etc.[1234] The larval form of filarial infection can be seen in various cytologic smears from different organs such as breast, thyroid, liver, salivary gland, soft tissues and bone marrow aspirates, etc.[23456] However, it is much rarer to find microfilaria in urine cytology smears.[234567]

In India, majority of the filarial infections are caused by W. bancrofti; accounting for approximately 95% of cases.[123] Filariasis is caused by nematodes group of parasites usually located in blood vessels, lymphatics, connective tissue, and serous cavities. W. bancrofti is the most common species found in India.[234] This is sheathed microfilaria with tail tip free from nuclei. W. bancrofti completes its life cycle in two hosts. Man is the definitive and mosquito is the intermediate host. Adult worms live in lymph nodes where the gravid females release microfilaria, which circulate in the peripheral circulation. These larval forms are injurious causing lymphangitis leading to further complications. During their transport in blood, they can get lodged in various organs causing different symptoms.

Patients with filariasis are usually asymptomatic but may present with varied clinical manifestations, that is, microfilaremia, lymphedema, hydrocele, acute adenolymphangitis, chronic lymphatic disease and rarely with the chyluria and tropical eosinophilia. Although chyluria is a known complication of filariasis, it is scarce to document filaria in achylous urine and may be due to lymphatic blockage by scars or tumors and damage to vessel walls by inflammation, trauma, or stasis.[4567]

Webber and Eveland were the first to report microfilaria in both voided as well as catheterized urine samples from a young male patient with intermittent painless hematuria.[1] There are few studies where microfilaria was noted in a urinary sample where there was clinical suspicion of malignancy, but computed tomography (CT) and cystoscopic findings were normal.[36] Vankalakunti et al.[3] and Ahuja et al.[6] noted similar findings in patients who presented with painless hematuria, but there was no evidence of malignancy based on radiological or cystoscopic findings. We also noted microfilaria in a patient with achylous hematuria; however, in our case, the patient presented with a mass lesion in the bladder on USG mimicking malignancy which is not only an unusual finding but also makes the presentation more interesting.

In the present case, cytological examination of day one urine sample showed many lymphoid cells with few degenerated forms and few eosinophils which raised the suspicion of malignancy/lymphoma, especially when correlated with radiology revealing a mass in the lumen of the bladder. However, subsequent examination of urine on 4 more consecutive days revealed the presence of microfilaria in the 2nd and 4th day urine sample along with benign urothelial cells, thereby excluding malignancy/lymphoma.

It is rare to document microfilaria in the urine sample of patient presenting with an exophytic lesion in the bladder.[57] A study by Jain et al.[5] documented a case of microfilaria in achylous urine with mass lesion in the bladder on CT scan. This case simulates the index case; however, in our patient, the presence of numerous lymphocytes was also noted which prompted us to exclude the presence of malignancy/nonHodgkin lymphoma. However, subsequent examination of urine samples in our case showed the presence of sheathed microfilaria of W. bancrofti.

Apart from an examination of peripheral blood, urine, and other body fluids for detecting microfilaria, serological markers can also be used.[5678] The patients with microfilaria develop IgG4 antibodies against W. bancrofti antigen Wb-SXP-1.[45678] As these patients can be easily treated with diethylcarbamazine (DEC), early and correct cytological diagnosis of filariasis is very important, especially in cases masquerading as malignancy based on clinical and radiological findings.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

The detection of microfilaria in achylous hematuria is very rare. A simple investigative modality can help in diagnosing urinary filariasis in cases where there is strong clinical suspicion of malignancy along with the presence of mass lesion in bladder on radiology. The parasite may not be seen at initial presentation; hence, a careful cytological examination of consecutive days urine sample should be done. Treatment is simple with DEC, hence timely intervention is very important to prevent any further complications.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL THE AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENTS BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE. Each author has participated sufficiently in work and takes public responsibility for appropriateness of content of this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is a quiz case, this case does not require approval from the Institutional Review Board.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

B. malayi - Brugia malayi

B. timori - Brugia timori

CT - Computed tomography

DEC - Diethylcarbamazine

PS - Peripheral smear

RBCs - Red blood cells

USG - Ultrasound sonography

W. bancrofti - Wuchereria bancrofti.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (the authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Cytologic detection of Wuchereria bancrofti microfilariae in urine collected during a routine workup for hematuria. Acta Cytol. 1982;26:837-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microfilariae of Wuchereria bancrofti in urine: An uncommon finding. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:847-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urinary filariasis masquerading as the bladder tumor: A case report with cyto-histological correlation. J Cytol. 2015;32:124-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microfilaria in a patient of achylous hematuria: A rare finding in urine cytology. J Cytol. 2012;29:147-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multisystem involvement of microfilaria in a HIV positive patient. Nepal Med Coll J. 2004;6:64-6.

- [Google Scholar]