Translate this page into:

Cytology of the fallopian tube: A screening model for high-grade serous carcinoma

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Ovarian cancer is a heterogeneous disease having the highest gynecologic fatality in the United States with a 5-year survival rate of 46.5%. Poor overall prognosis is mostly attributed to inadequate screening tools, and the majority of diagnoses occur at late stages of the disease. Due to genetic and biological underpinnings, ovarian high-grade serous carcinomas (HGSC) have etiologic evidence in the distal fallopian tube. Fallopian tube screening modalities are aggressively investigated, but few describe cytological characteristics of benign tubal specimens to help in the comparative detection of HGSC precursor cells. Here, we describe fimbrial cytomorphological and nuclear features of tubal specimens (n = 75) from patients clinically indicated for salpingectomy, bilateral or unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and hysterectomies for any diagnosis other than ovarian or peritoneal cancer. Fallopian tube histology was used as the diagnostic reference. A total of 75 samples had benign diagnoses. The benign cytological characteristics of fimbrial tubal specimens included ciliated cells in clustered arrangements with mild nuclear membrane irregularity, mild anisonucleosis, round and/or oval nuclei, hyperchromatic chromatin, and mild nuclear membrane irregularity. In contrast, none of the cytology samples had spindle-shaped nuclei, significantly marked anisonucleosis (n = 1), nor had hypochromasia as a characteristic feature. These cytological characteristics could be a potential area of distinction from HGSC precursor cells. Our study establishes cytomorphological characteristics of nonmalignant tubal cells which help underscore the importance of distinguishing malignant HGSC precursors through fimbrial brush sampling in minimally invasive approach.

Keywords

Cytology

fallopian tube

ovarian cancer

screening

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian malignancies have the highest gynecologic fatalities in the United States with a 5-year survival rate of 46.5% but yet accounting for only 3% of cancers diagnosed in women.[1] Approximately 80% of cases are reported in women over 50 years old, and the median age of diagnosis is 63.[12] With the increasing aging population, early detection will become paramount to counter the burden of cancer due to changes in population risks,[34] especially since earlier stages of diagnosis of ovarian cancer are associated with a much better 5-year relative survival rate of 73.0%–92.5%.[1] The poor overall prognosis is mostly attributed to inadequate screening tools and additionally because the majority (>80%) of ovarian cancer diagnoses are rendered in the later stages of the disease (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) Stages III and IV).[567]

Ovarian cancer is a heterogeneous disease categorized by histopathological features, of which high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) is the most common, aggressive, and lethal subtype.[89] HGSC accounts for 75% of ovarian carcinomas and accounts for 90% of the mortalities.[68] A considerable paradigm shift in our understanding of the primary site of HGSC, due to the implications of molecular and genetic evidence, suggests that serous neoplasms originating from the ovaries, peritoneum, and fallopian tube should be considered collectively.[81011] This postulate is based on studies of women with BRCA1/2 mutations having HGSC precursor lesions in the secretory epithelial cells of their fallopian tubes.[5] The precursor lesion was termed the “p53 signature” and corresponds to the identical TP53 gene mutation present in ovarian, fallopian, and peritoneal HGSCs.[5] While the molecular antecedents to HGSCs are multifactorial, it is proposed that serous precursors cells with molecular alterations of TP53 in the fimbriae of the fallopian tube grow preferentially at remote peritoneal areas.[6712] Due to the specificity of TP53 to HGSC as an early event in its disease sequelae, fimbrial cell sampling should be explored as a screening tool and studied for prognostic biomarkers.[610]

There are only three-documented randomized studies evaluating screening tools for ovarian cancer: the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Randomized Control Trial, The Shizuoka Cohort Study of Ovarian Cancer Screening (SCSOCS), and the United Kingdom Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS).[131415] The PLCO trial did not show any decrease in mortality when women aged 55–74 were screened annually from 1993 to 2001 for ovarian cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) and transvaginal ultrasound.[13] Furthermore, the results showed that false positives were associated with unnecessary clinical workup and complications. The SCSOCS and UKCTOCS trials which similarly screened postmenopausal women showed similar results and no difference in detection of ovarian cancer.[1415] Based on those trials, no adequate sensitivity, specificity, or mortality rate was justified to predict ovarian cancer prognosis or early intervention. Henceforth, identifying serous precursor cells from the fallopian tube may portend early ovarian detection.

Multiple avenues of screening have been described in sampling fallopian tube cells. A few preliminary studies have shown that serous neoplastic cells detected in endometrial samples were associated with HGSCs, albeit with low sensitivity.[1617] Most notably, insights from studies analyzing fimbrial cytology have shown strong correlations with histological findings diagnostic of HGSCs.[111819] There are limitations to the studies as they are conducted mostly in women who underwent prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy as a risk-reducing intervention for BRCA1/2 germline mutation. Furthermore, there are few cytological studies of the fallopian tubes in women without BRCA1/2, due to the low incidence of serous tubal intraepithelial neoplasms.[1820] Here, we describe the cytomorphologic characteristics of fimbriae sampling during minimally invasive laparoscopic screening. Our goal also is to determine its effectiveness as a method to screen for HGSC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida, and informed consent was obtained for each patient. A total of 75 specimens were collected from 39 patients from March 1 to April 30, 2014, undergoing clinically indicated salpingectomy, bilateral or unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and hysterectomies for any diagnosis other than ovarian or peritoneal cancer. Clinical and pathologic information was collected including age, indication for the operative procedure, laterality, type of procedure (hysterectomy and/or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy), and the final histologic pathologic diagnosis.

Cytological samples were collected prospectively by brushing the fallopian tube fimbria with a pap cytobrush. The samples were collected ex vivo immediately after removal of the specimen. Subsequently, the samples were stored in SurePath™ liquid specimen vials until Papanicolaou stain slide preparation was performed. The cytomorphology was described and correlated with the final histologic diagnosis. The cytologic evaluations were performed by a board-certified cytopathologist (AN) to capture key cytologic features. The features include background (clean, granular, and bloody); cellularity (low, moderate, and high) as determined on both number of cells and cell groups; artifact (not significant and crush); architecture (clusters, single cells, and honeycomb monolayered sheets); cilia (absent or present); anisonucleosis (mild, moderate, and marked); nuclear pleomorphism (none, mild, moderate, and marked); the presence of nucleoli (inconspicuous, single, and multiple); chromatin (hypochromatic, hyperchromatic, and mixed chromatin); nuclear shape (spindle, round, oval, and mixed shapes); nuclear membrane irregularity (none, mild, and moderate); and bare nuclei (present and absent).

Continuous variables are summarized as mean (±standard deviation) and median (range). Categorical variables are reported as frequency (percentage). Sample characteristics are summarized by fallopian tube laterality (right versus left). All statistical analysis was performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

RESULTS

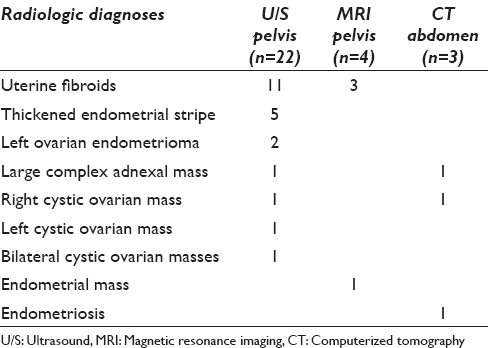

A total of 75 specimens were collected from 39 patients with an average age of 55.1 (±14.5) (median age: 52, age range: 33–89). A total of 31 (79.5%) patients identified as White, 5 (15.4%) identified as African American, 2 (5.1%) identified as Hispanic, and 1 (2.6%) did not disclose their race [Table 1]. The indications for the surgeries included abdominal-pelvic masses, abnormal uterine bleeding, leiomyomas, endometrial pathologies, uterine prolapse, and/or prophylaxis. Cytological samples were obtained from both the right and left fallopian tubes, one patient only had the left fallopian tube sampled, and two patients only had the right fallopian tube sampled [Table 1]. In addition, the radiologic imaging findings were available on 29 patients (29/39, 74.4%) [Table 2].

Cytomorphologic features

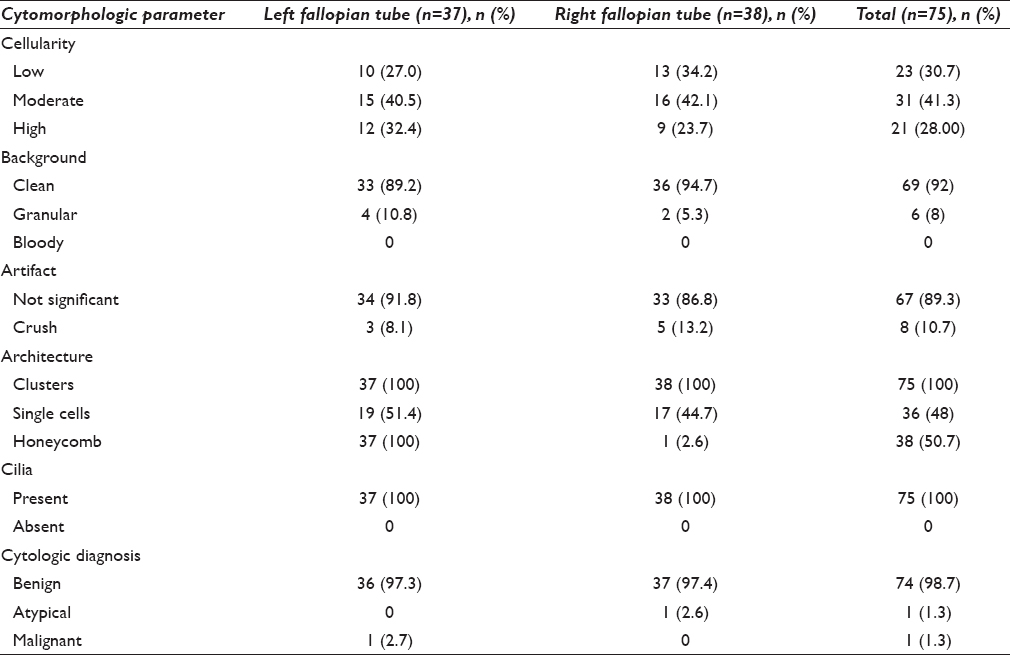

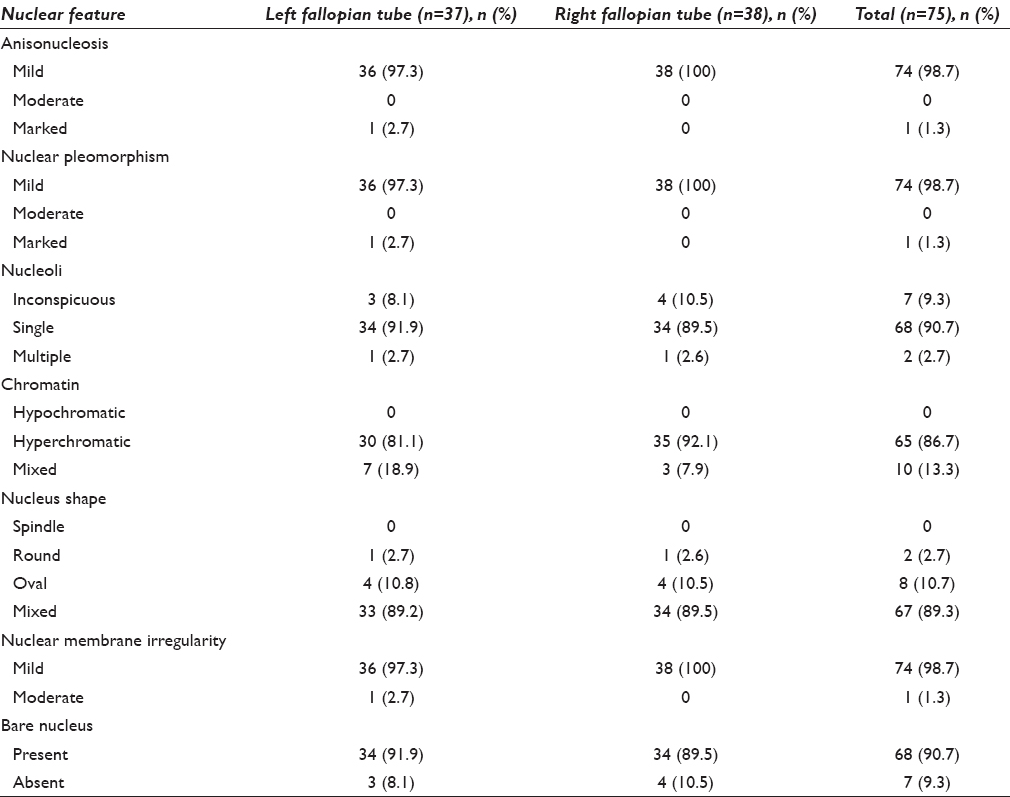

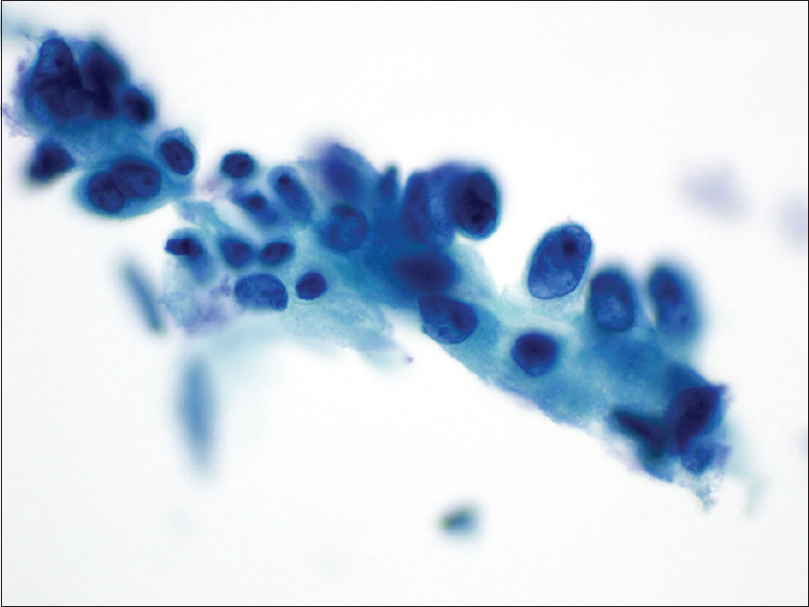

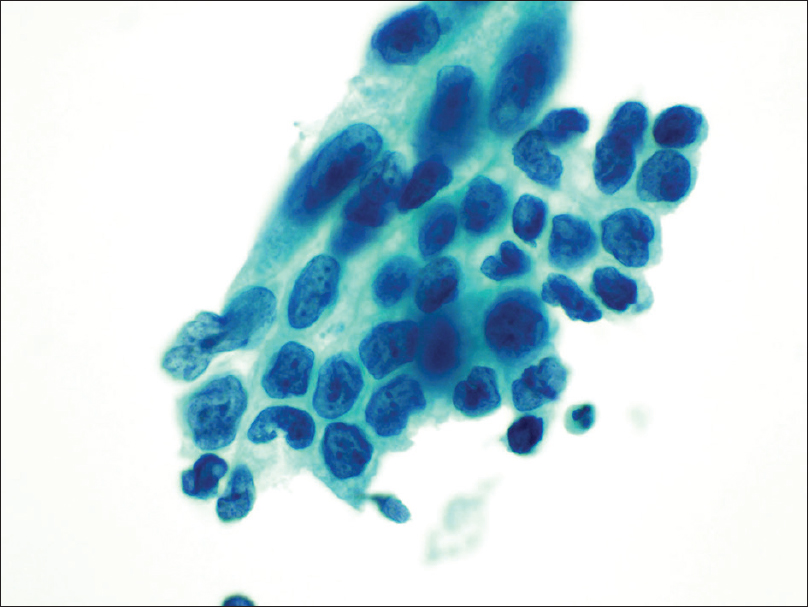

All the collected specimens had ciliated columnar cells arranged in clusters [Figure 1] and were deemed as satisfactory for evaluation. There was one specimen collected from the left fallopian tube which had an unavoidable sampling error. In the left fallopian specimens (n = 37), 10 specimens had low cellularity, and the remaining 27 had moderate-to-high cellularity. In the right fallopian tube samples (n = 38), 13 specimens had low cellularity, and the remaining 25 had moderate to high cellularity; a total of 69.3% of samples had moderate-to-high cellularity [Table 3]. The background was clean for 33 left fallopian tube samples and was granular for 4 left fallopian tube samples. For the right fallopian tube samples, 36 specimens had a clean background, and 2 had a granular background. In total, 92% of the specimens had a clean background, and none of them had a bloody background. Moderate crush artifacts were found in 3 of the left fallopian tube specimens and 5 of the right fallopian tube specimens; this accounts for 10.7% of all the specimens [Table 3]. All of the left fallopian tube specimens were arranged in honeycomb/monolayered sheets [Figure 2]. All of the right fallopian tube specimens were arranged in tight clusters (100.0%); 17 (44.7%) of which also had single-scattered cells in the background.

- A cluster of a columnar and cuboidal epithelium with a terminal bar (Papanicolaou stain, ×20)

- A monolayered sheet of columnar and cuboidal epithelium (Papanicolaou stain, ×20)

Nuclear features

Mild anisonucleosis and nuclear pleomorphism were observed in 36 of the 37 left fallopian tube specimens and all 38 right fallopian tube specimens, accounting for 98.7% of the total specimens [Table 4]. These characteristics were associated with benign cytological and negative histological diagnosis. Only one specimen of benign histologic diagnosis had marked anisonucleosis and nuclear pleomorphism (left fallopian tube), and this was called malignant based on cytologic features (cytohistologic correlation). The majority of the right and left specimens had single nucleoli (total of 90.7% of specimens; 34 left and 34 right). A total of seven samples had cells with inconspicuous nucleoli, and only two specimens from separate patients (one left and one right fallopian tube) had multiple nucleoli. Most of the specimens had hyperchromatic nuclei (a total of 86.7%, 65/75), and a total of 10 specimens had mixed chromatin features (hypo- and hyperchromasia). There was a mixture of oval, round, and mixed (oval and round) nuclear shapes in the specimens, and none were found to have spindle characteristics. In the left fallopian tube specimens, four had oval-shaped nuclei of which one also had a round-shaped nucleus. A total of 33 left specimens had mixed shaped nuclei. In the right fallopian tube specimens, four had oval-shaped nuclei of which one was also round (from the same patient with the left fallopian tube specimen with round nuclei). A total of 34 patients had mixed nuclear shapes. The majority of the specimens had mild nuclear membrane irregularity (36 left and 38 right; 98.7%), nothing pronounced was observed except in one specimen collected in the left fallopian tube. The majority of the specimens have bare nuclei (68 total; 90.7%) [Table 4].

Cytohistologic correlation

The histologic diagnosis for the majority of fallopian tubes sampled (38/39, 97.4%) was benign with few paratubal cysts in 12 cases (12/39, 30.8%), except for one case (1/39, 2.6%) who was diagnosed as focal tubal serous intraepithelial carcinoma on the right fallopian tube. That particular case was called benign on cytology because of sampling error. There were two additional discrepant cases that were called “suspicious for malignancy” and “positive for malignancy” on cytology. The first case that was called “rare cluster of atypical cells present suspicious for adenocarcinoma” cytologically on the right fallopian tube [Figure 3], the corresponding histology revealed a well-differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma of the right ovary (pT1a– Stage IA). The second case that was called “malignant on cytology” with marked nuclear pleomorphism and multiple nucleoli of the left fallopian tube [Figure 4]; the histology revealed a FIGO Grade 2 endometrioid adenocarcinoma (4.5 cm in diameter) invading 1.5 cm into the underlying myometrium (pT1b– Stage IB). Both these discrepant cases represent possible contamination from the operative procedure, as in both cases, the fallopian tube histologic findings were benign.

- Cluster of atypical glandular epithelium of a right fallopian tube with nuclear overlap and crowding, with high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, coarse chromatin, and prominent nucleoli (Papanicolaou stain, ×40); corresponding histology was a well-differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ovary

- Cohesive cluster of atypical epithelial cells with marked nuclear pleomorphism, high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, coarse chromatin, multiple prominent nucleoli, and membrane irregularity (Papanicolaou stain, ×40); corresponding histology was a Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Grade 2 endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterus

DISCUSSION

Since the screening studies that investigated the utility of serum CA-125 and ultrasound did not improve survival rate, other screening modalities are aggressively pursued for ovarian HGSC.[13141518] Based on our current understanding of serous ovarian carcinogenesis, evidence pinpoints the etiologic significance of distal fallopian tubes.[111820] In keeping with this model, tubal lesions can potentially become a focal screening point for early detection of HGSC. Therefore, accurately detecting ovarian HGSC in its earlier stages is a promising concept which could provide earlier staging, adequate classification, and better prognostic outcomes. It has been shown that cytological diagnoses from fallopian fimbrial samples were correlative to histological diagnoses of HGSC.[18] However, due to the limited sample size that came from patients who already had clinical symptoms, the external validity is limited. Particularly given that the patients enrolled in those studies already had obvious clinical manifestations, which is attributed to advanced stages of the disease. Those results may not adequately reflect cytological characteristics that would be found in earlier stages. Furthermore, there is a minimal focus on characterizing benign cytomorphological and nuclear features of fimbrial cells.[19] It is important to define benign fimbrial cytology to better determine the sensitivity and specificity of this screening methodology. Our study provides 75 cytological samples of which 74 samples had benign histological diagnoses and 1 was focal tubal serous intraepithelial carcinoma.

The benign cytological characteristics of fimbrial tubal specimens included ciliated cells in clustered arrangements with mild nuclear membrane irregularity, mild anisonucleosis, round and/or oval nuclei, hyperchromatic chromatin, and mild nuclear membrane irregularity. Establishing these features as benign is particularly important because it can help establish a baseline consensus for nonmalignant fimbrial cytology.[19] Accordingly, understanding normal cytology can potentially help improve diagnostic accuracy and reproducibility. In contrast, none of the cytology samples had spindle-shaped nuclei, significantly marked anisonucleosis (n = 1), nor had hypochromasia as a characteristic feature. These cytological characteristics could be a potential area of distinction from HGSC precursor cells and benign tubal cells which merits further exploration. Due to an unavoidable sampling error that occurred in the fimbrial sample with the focal tubal serous intraepithelial carcinoma histological diagnosis (n = 1), these characteristics could not be statistically assessed in this study.

Currently, our understanding is that the most prominent malignant cytological features are three-dimensional clusters (compared to the small <3-cell cluster) and large cherry red nucleoli.[18] By the same token, this is from a study with a small sample size; hence, further studies are warranted to demonstrate correlative associations. The malignant cytological diagnosis in our study (n = 1) [Table 1] corresponded to a patient with the clinical presentation of endometrial cancer, and the atypical cytological diagnosis (n = 1) corresponded to a menopausal patient with ovarian mucinous adenocarcinoma. Interestingly, the fimbrial cytological diagnoses were not consistent with the tubal histological diagnoses; both samples were negative for any malignancy. We postulate that the cytobrush might have removed the focal lesion in the histological sample as previously reported in other fimbrial cytological sampling.[18]

It is important to note that the sequence of events that occur in tubal carcinogenesis occurs over a spectrum. It is widely accepted that the molecular antecedents that precede the transition from “normal” (chiefly p53 signatures) to neoplastic growth take place before cytomorphological and histopathological changes.[69] Henceforth, as part of a developing protocol for early HGSC detection, immunohistochemistry showing evidence of p53 mutations would need to be implemented. Further studies are being considered to implement the p53 immunostaining with this form of screening modality. Since the pathways leading to neoplastic transformation are multimodal, paired box gene 8 expression (Pax 8), a Müllerian lineage marker expressed by nonciliated secretory cells could also be used for further HGSC classification.[5]

Based on this presumed tubal site of origin, our findings are aimed at directing efforts for early detection and prevention of HGSC. Using fimbrial cytological sampling could potentially establish baseline cytomorphological characteristics of HGSC precursor lesions that are correlative to histological diagnoses. Further studies are needed to establish a broader acceptable approach for cytological fimbrial sampling. Our study nevertheless establishes cytomorphological characteristics of nonmalignant cells which help underscore the importance of distinguishing malignant HGSC precursors through fimbrial brush sampling in minimally invasive procedures.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

There is no conflict of interest to disclose by all authors.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors have contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, manuscript's initial and final draft writing.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors have followed the ethical guidelines for Human subjects research according to the declaration of Helsinki and institutional review board.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

CA-125 - Cancer antigen 125

FIGO - International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

HGSC - High-grade serous carcinoma

PAX-8 - Paired box gene 8

SCSOCS - Shizuoka Cohort Study of ovarian cancer screening

UKCTOCS - United Kingdom Collaboration Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This manuscript was presented as a platform oral presentation at the 43rd Annual Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists Global Congress of Minimally Invasive Gynecology on November 19, 2014, in Vancouver, BC, Canada.

REFERENCES

- SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2015, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015/

- [Google Scholar]

- Ten-year relative survival for epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:612-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Next Four Decades, The Older Population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. Report No.: P25-1138. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau; 2010.

- [Google Scholar]

- The past, present, and future of cancer incidence in the United States: 1975 through 2020. Cancer. 2015;121:1827-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modeling high-grade serous ovarian carcinogenesis from the fallopian tube. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7547-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular alterations of TP53 are a defining feature of ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma: A Rereview of cases lacking TP53 mutations in the cancer genome atlas ovarian study. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2016;35:48-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ovarian low-grade and high-grade serous carcinoma: Pathogenesis, clinicopathologic and molecular biologic features, and diagnostic problems. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:267-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surface epithelial tumors of the ovary. In: Kurman RJ, Ellenson LH, Ronnett BM, eds. Blaustein's Pathology of the Female Genital Tract (6th ed). New York: Springer; 2011. p. :680-772.

- [Google Scholar]

- A candidate precursor to serous carcinoma that originates in the distal fallopian tube. J Pathol. 2007;211:26-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131(Suppl 2):S111-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: Evidence for a causal relationship. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:161-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: Its potential role in primary peritoneal serous carcinoma and serous cancer prevention. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4160-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of screening on ovarian cancer mortality: The prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305:2295-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ovarian cancer screening and mortality in the UK collaborative trial of ovarian cancer screening (UKCTOCS): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:945-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- A randomized study of screening for ovarian cancer: A multicenter study in Japan. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:414-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early detection of ovarian and fallopian tube cancer by examination of cytological samples from the endometrial cavity. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:603-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma arising from the intrauterine portion of the fallopian tube after bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2016;37:404-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tubal cytology of the fallopian tube as a promising tool for ovarian cancer early detection. 2017. J Vis Exp. 125 doi: 10.3791/55887; Published: 7/25/2017 Available from: https://www.jove.com/video/55887/tubal-cytology-fallopian-tube-as-promising-tool-for-ovarian-cancer

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic findings in experimental in vivo fallopian tube brush specimens. Acta Cytol. 2013;57:611-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Frequency of “incidental” serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC) in women without a history of or genetic risk factor for high-grade serous carcinoma: A six-year study. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146:69-73.

- [Google Scholar]