Translate this page into:

Cytomorphology of Boerhaave's syndrome: A critical value in cytology

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Spontaneous esophageal perforation into the pleural cavity (Boerhaave's syndrome) is a rare life-threatening condition, which requires early diagnosis and urgent management. The diagnosis of such critical condition in many cases is delayed because of atypical clinical presentation, resulting in increased morbidity and mortality. Cytological examination of pleural fluid can provide early, fast and accurate diagnosis of such critical condition and help in better and early management of this disease. We describe a case of an 81-year-old female with esophageal perforation who presented with a left sided pleural effusion. The correct diagnosis was established in this case by observing gastrointestinal-like fluid characteristics of the thoracic drainage upon cytological and chemical analyses and the rupture was confirmed by esophagography. The cytological examination of pleural fluid revealed benign reactive squamous cells, fungal organisms, bacterial colonies, and vegetable material consistent with a ruptured esophagus. Cytological examination of pleural fluid is a rapid and accurate technique that can help in establishing the diagnosis of this challenging entity and guide initiation proper management of this unusual entity.

Keywords

Boerhaave's syndrome

critical value

pleural fluid

spontaneous esophageal perforation

INTRODUCTION

Pleural effusions can be caused by many diseases and conditions. The serous fluid can be classified as either transudate or exudate. Common causes of transudative effusion include congestive heart failure, cirrhosis, and nephrotic syndrome. Exudates can be caused by conditions such as malignancy, pneumonia, lupus, rheumatoid pleuritis, pulmonary infarction, and trauma.[1] Pleural fluid analysis is useful in supporting the clinical diagnosis and in providing definitive diagnosis in certain circumstances.[123]

Spontaneous esophageal perforation (Boerhaave's syndrome) into the pleural cavity is a rare cause of exudative pleural effusion. Delayed diagnosis of this condition can cause high morbidity and mortality; cytological examination can be the first clue to this condition and contribute to early diagnosis and management of this critical condition.[3] We report a case of an 81-year-old female with a spontaneous esophageal perforation that remained undiagnosed for several days. A discussion on the role of cytological examination of pleural fluid, differential diagnosis, and the significance of early reporting of such condition as a critical value (CV) is presented.

CASE REPORT

Clinical features

An 81-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension, hypothyroidism, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, hyperlipidemia and chronic kidney disease presented with abdominal pain and vomiting after eating food. There were no complaints of chest pain, shortness of breath, cough or hemoptysis. Physical examination elicited pain scaled around 3-4/10 localized in the epigastric area. X-ray of the abdomen showed air-filled non-distended large and small bowel loops without impaction or obstruction. The initial clinical impression was gastroenteritis. A chest radiograph done on the following day of patient's presentation showed newly developed patchy areas of increased attenuation in the left lung base with an associated pleural effusion. A left sided chest tube was inserted and drained nearly 600 cc of gastrointestinal content-like fluid which was submitted for cytological and chemical examinations.

Chemical and cytological examinations of pleural fluid with follow-up

The pleural fluid analysis of this case showed lactate dehydrogenase of 3405 units/L, amylase of 5192 units/L (i.e., high), glucose 23 mg/dl (i.e., low) and pH of 7.0 (i.e., low). The white cell count was 4838/cumm and red blood cell count was 4000/cumm, supporting an exudative/inflammatory nature for this specimen and consistent with a diagnosis of ruptured esophagus.

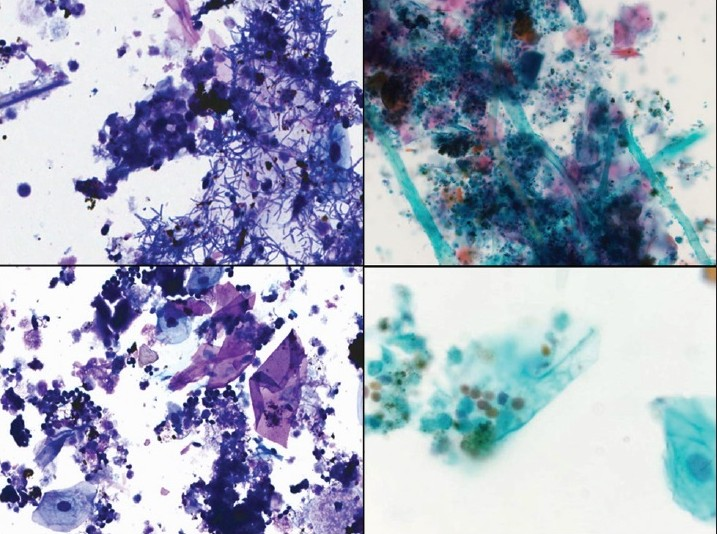

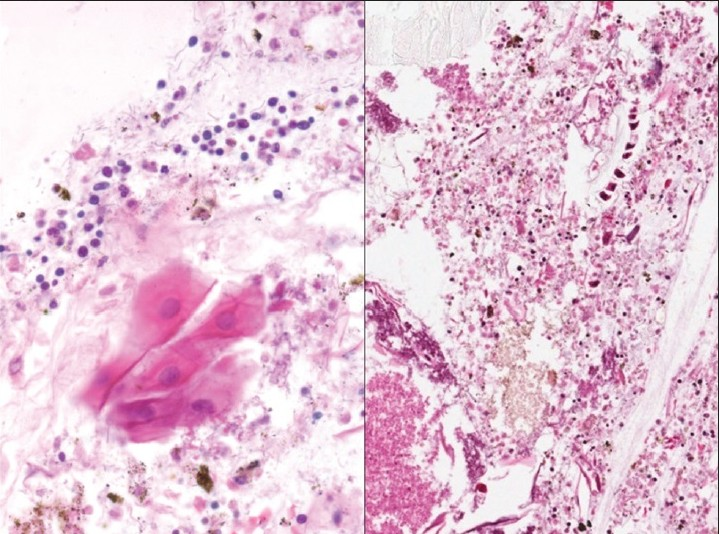

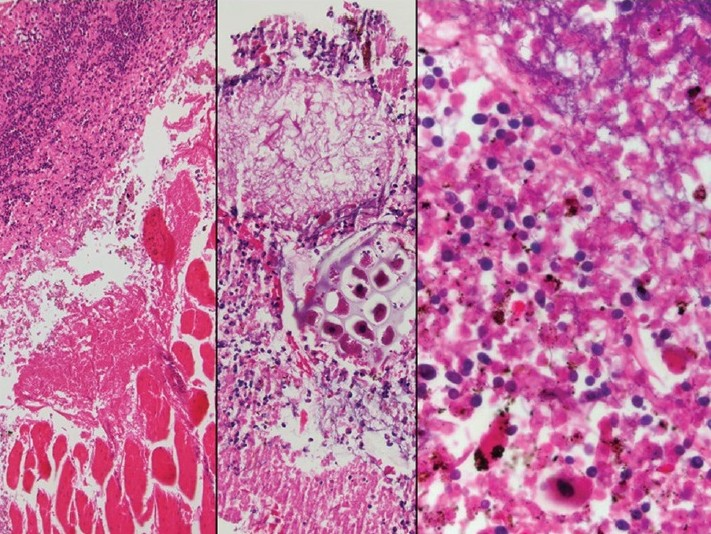

The gross appearance of the specimen submitted for cytological examination showed thick, chunky, light brown, opaque fluid containing numerous pale tan and pale brown fragments. The cytological examination of the left pleural fluid revealed benign squamous cells, bacterial colonies, and fungal organisms consistent with candida, and vegetable material [Figures 1 and 2]; these combined features are most consistent with a ruptured esophagus. Spontaneous esophageal perforation is known as Boerhaave's syndrome. This is considered a CV for which the clinician has to be notified as soon as possible. The clinician was called immediately, and the patient underwent surgical esophageal repair of the esophageal rupture and left decortications of the pleura. The surgical specimen showed pieces of necrotic soft-tissue, bile, bacterial, and fungal colonies, vegetable material, and an acute inflammatory exudate [Figure 3].

- Pleural fluid showing benign squamous cells, debris, bacterial colonies, and fungal colonies consistent with candida. Diff Quik stain, ×400 (left), and Papanicolaou stain, ×200 (right upper) and ×400 (right lower)

- Cell block of pleural fluid showing benign squamous cells, debris, bacterial colonies, and fungal colonies consistent with candida. H and E, stain, ×400, left and ×200, right. The right image shows also vegetable material

- The surgical specimen of esophageal repair and decortications showing inflammatory exudate involving skeletal muscle (left) and containing vegetable materials (middle), and benign squamous cells bacterial and fungal colonies (right). H and E stain, ×100 (left); ×200 (middle), and ×400 (right)

DISCUSSION

Spontaneous esophageal perforation or Boerhaave's syndrome is a life threatening condition that demands early diagnosis and urgent management. The diagnosis may be delayed or unrecognized because the presenting clinical symptoms mimic other common conditions; as a result, the initial crucial therapeutic intervention can be delayed.[34] However, a careful clinical history, knowledge of the symptomatology of this condition, and careful study of the imaging findings (chest X-ray) help to reach an early diagnosis and to initiate the proper surgical intervention with a rewarding outcome. The most common reason for delayed diagnosis is the fact that spontaneous rupture of the esophagus often mimics other more common conditions such as acute cardiothoracic or upper gastrointestinal disorders.[34]

Boerhaave's syndrome was first described in 1724 by a Dutch physician, Dr. Hermann Boerhaave.[5] The perforation in Boerhaave's syndrome is thought to be caused by the rapid rise in esophageal intraluminal pressure, with the classic clinical presentation consisting of vomiting, lower thoracic pain, and subcutaneous emphysema. However, many patients present atypically resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment.[67] In a review by Teh et al.,[8] diagnosis was delayed in 20 patients out of 34 included in the study with a median delay of 4 days. The chest X-ray can demonstrate a pleural effusion, usually on the left side, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax.[9] Contrast esophagography and computed tomography scan can be used to confirm the diagnosis. Another useful diagnostic modality to diagnose esophageal perforation is thoracocentesis and pleural fluid examination.[8] The pleural effusions seen in the context of Boerhaave's syndrome typically exhibit low pH and low glucose level.[10] The differential diagnosis of pleural effusion with low pH includes, empyema, malignancy, rheumatoid disease, hemothorax, systemic acidosis, and para-pneumonic effusion.

Cytological examination of pleural fluid in esophageal perforation may show the presence of benign squamous epithelial cells. In a study by Ishiguro et al.,[11] the presence of squamous epithelial cells were described in 4 out of 6 cases with esophageal perforation. In the same study,[11] one patient was found to have benign squamous epithelial cells in the absence of gastrointestinal perforation; this patient had developed empyema due to perforation of a lung abscess into the pleural cavity and histological examination of the surgically resected lung tissue showed squamous metaplasia. The differential diagnosis also includes metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the lung which is a rare cause of malignant pleural effusion. The cytological appearance shows some degree of cytological and architectural atypia of the squamous cells (unlike the benign-looking squamous cells seen in our case) depending on the degree of keratinization of the tumor. Non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma is more commonly seen in effusions than the keratinizing type. The non-keratinizing malignant squamous cells can mimic adenocarcinoma or markedly reactive mesothelial cells. The differential diagnosis of well differentiated keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma may include contamination with squamous cells from the epidermis removed during aspiration; this is a rare event and usually results in the presence of only a few such benign squamous cells or fragments of skin epidermis.[12] Some other rare causes of pleural effusion with squamous cells have been described in the literature. Malignant pleural effusions can rarely be seen in patients with metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus,[13] cervix[14] or penis. Benign squamous cells have also been described in an instance of rupture of a mediastinal benign cystic teratoma into a pleural space.[15]

Isolation of candida from a pleural effusion is a clue for suspecting esophageal perforation as candida are normal commensals in the gastrointestinal tract. Detection of food particles in the pleural fluid is diagnostic of esophageal perforation, but ingested material is not always present. The food particles can be detected by gross examination of the thoracic drainage,[15] or by cytological examination.[16] It has been suggested that the cytological detection of food material is enhanced by high speed centrifugation of the pleural fluid. The food particles may not be detectable on gram stain or wet preparations.[1016] Drainage of previously swallowed tracer fluids like methylene blue or barium may also help to confirm the diagnosis in some patients.[6]

The idea of CV was introduced by Lundberg in 1972,[17] as “pathophysiological derangements at such variance with normal as to be life-threatening if therapy is not instituted immediately.” Boerhaave's syndrome is one of the CVs in cytology that requires immediate contact of the physician to rapidly initiate treatment.

In summary, Boerhaave's syndrome is a life threatening condition that demands early diagnosis and urgent management. The important laboratory findings are high amylase, low pH, and low glucose. Cytological examination shows the presence of benign squamous epithelial cells, ingested food material, and candida. The cytological and chemical analyses of pleural fluid are rapid techniques that can point to the correct diagnosis in the majority of cases in this rare but highly critical condition.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and granted exempt status. We take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2013/10/1/8/111811

REFERENCES

- Diagnosis and management of spontaneous transmural rupture of the oesophagus (Boerhaave's syndrome) Br J Surg. 1985;72:204-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hermann Boerhaave's Atrocis, nec descripti prius, morbi historia, the first translation of the classic case report of rupture of the esophagus, with annotations. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1955;43:217-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Our experience on management of Boerhaave's syndrome with late presentation. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:62-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Boerhaave syndrome: A diagnostic conundrum. BMJ Case Rep 2009 February 20 doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2008.0375

- [Google Scholar]

- Boerhaave's syndrome: A review of management and outcome. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007;6:640-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Boerhaave's syndrome - Rapidly evolving pleural effusion; a radiographic clue. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76:865-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation of Candida species is an important clue for suspecting gastrointestinal tract perforation as a cause of empyema. Intern Med. 2010;49:1957-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effusions in the presence of cancer. In: Koss LG, ed. Koss’ Diagnostic Cytology (5th ed). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006. p. :949-1022.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytology of metastatic cervical squamous cell carcinoma in pleural fluid: Report of a case confirmed by human papillomavirus typing. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:381-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic findings in an effusion caused by rupture of a benign cystic teratoma of the mediastinum into a serous cavity. Acta Cytol. 1985;29:1015-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic value of pleural fluid cytology in occult Boerhaave's syndrome. Chest. 1992;102:976-8.

- [Google Scholar]