Translate this page into:

Cytomorphology of giant cell tumor of bone in pleural fluid

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

To the Editor,

Giant cell tumor (GCT) of the bone or osteoclastoma is generally a benign and locally invasive tumor that occurs close to the joint of a mature bone.[1] GCT is an aggressive lesion that behaves in an unpredictable fashion.[2] The rate of recurrence is high and it metastasizes to the lungs, in approximately 2 – 3% of the patients.[3] Metastatic lung nodules can present at the time of initial surgery or develop many years after the appearance of the primary tumor.[4] The primary and metastatic lesions usually have the same histological features of a benign tumor; however, malignant tumors with giant cells have been noted in some cases, on a retrospective review.[5]

Although several cases of GCT with pulmonary metastases diagnosed on biopsy have been described, only four cases diagnosed by fine needle aspiration biopsy have been documented in the cytological literature. All the cases previously described, have presented with multiple pulmonary nodules.[6]

We herein report a case of osteoclastoma metastatic to the lung in an 18 year-old female, who presented with pleural effusion, and a diagnosis of metastatic GCT was established initially, based on the pleural effusion cytology smears. To the best of our knowledge, no similar case has been previously documented in the literature, with such a presentation of pleural effusion and diagnosis based on effusion cytology.

A 16-year-old female with left leg pain was detected to have a left distal femur lesion, in February 2010. The radiograph showed an eccentric lytic lesion in the left distal femur with soft tissue extension. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) demonstrated a well-defined, smoothly marginated, heterogeneously enhancing mass lesion, involving the epimetaphyseal region of the lower femur, which was hypointense on T1-weighted and predominantly hyperintense on T2-weighted images. She was treated with curettage. A diagnosis of giant cell tumor was made on histopathological examination.

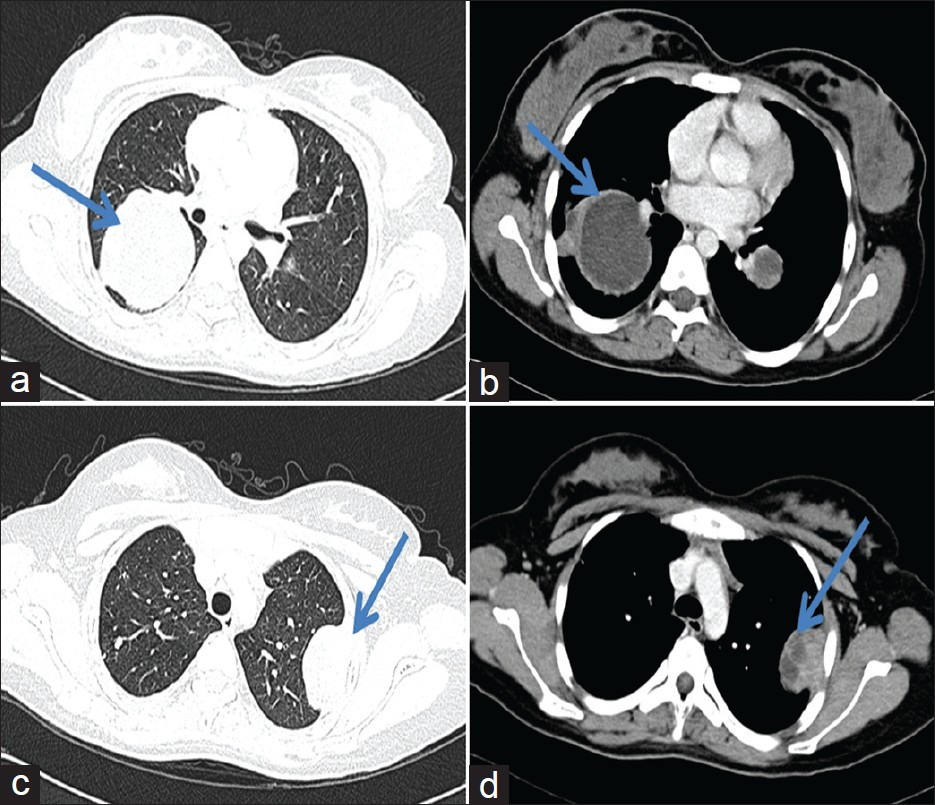

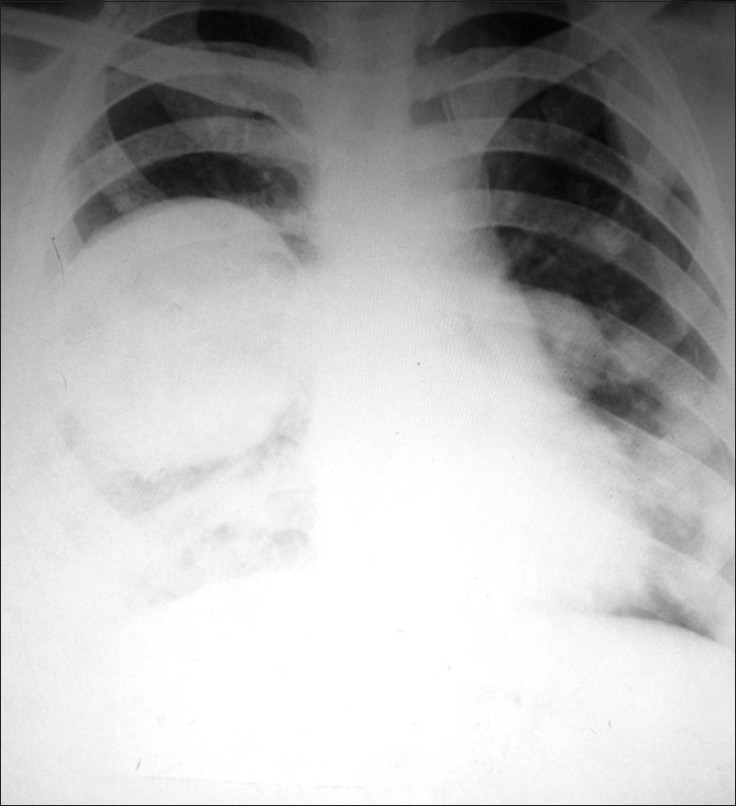

One-and-a-half years later, she presented with a complaint of pain in the anterior chest. A Computed Tomography (CT) scan revealed multiple rounded lesions, with peripheral enhancement and central necrosis in both the lungs. One of the lesions in the left upper lobe and one in the right middle lobe were pleural-based [Figures 1a–d]. All the radiological findings suggested multiple bilateral pulmonary metastases. Two months later, she developed dyspnea and the chest radiograph revealed right-sided pleural effusion, along with the lung lesions [Figure 2]. A pleural tap was performed and 150 ml of pleural fluid was sent for cytopathological evaluation.

- (a-d) CT scan demonstrating lesions in the right middle lobe and left upper lobe, both of which are pleural-based with chest wall invasion

- Chest radiograph revealing right-sided lung lesion along with pleural effusion

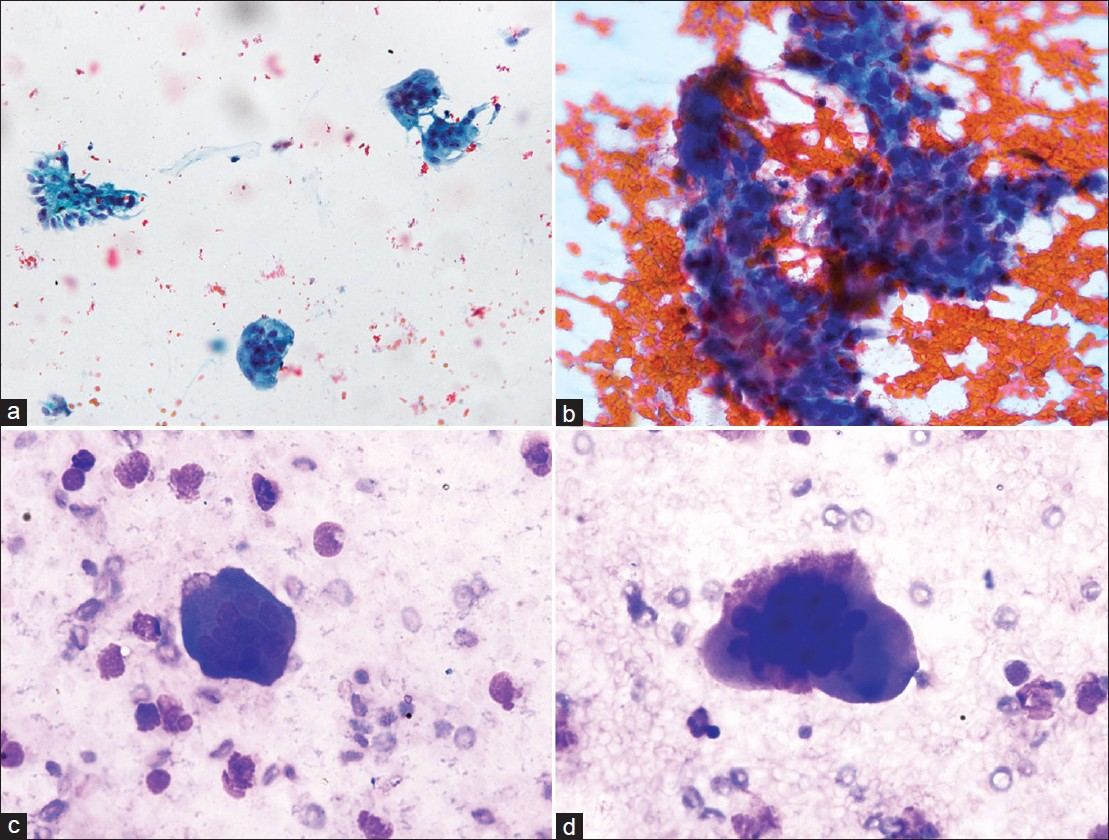

Microscopic examination showed many osteoclast giant cells with few interspersed mononuclear cells, numerous foamy histiocytes, and few mesothelial cells [Figures 3a–c]. The findings led us to suspect a diagnosis of GCT, metastatic to the lung, involving the pleura and producing pleural effusion.

![(a-b) Microphotograph of pleural fluid showing osteoclast-like giant cells, with interspersed foamy histiocytes [(a) (Pap, 200×), (b) (MGG, 200×); (c) Osteoclast giant cell sticking to the mononuclear cells (MGG, 400×)]; (d) Biopsy of the lung lesion showing features of giant cell tumor (H and E, 200×)]](/content/105/2012/9/1/img/CJ-9-22-g003.png)

- (a-b) Microphotograph of pleural fluid showing osteoclast-like giant cells, with interspersed foamy histiocytes [(a) (Pap, 200×), (b) (MGG, 200×); (c) Osteoclast giant cell sticking to the mononuclear cells (MGG, 400×)]; (d) Biopsy of the lung lesion showing features of giant cell tumor (H and E, 200×)]

The differentials of rheumatoid arthritis, herpes viral infection, giant cell carcinoma, carcinosarcoma, mesothelioma, radiotherapy, granulomatous inflammation, and surgical intervention were considered as they have been rarely associated with the presence of giant cells in pleural effusions. Lack of elongated giant cells and macrophages along with granular necrotic debri ruled out rheumatoid arthritis. There were no nuclear inclusions suggestive of herpetic infection. Giant cell carcinoma, carcinosarcoma, and mesothelioma were excluded because of the absence of bizarre cells. Moreover, the clinical presentation and radiological investigations helped in ruling out all the differentials, including granulomatous inflammation. There was no history of radiotherapy or surgical intervention.

This was followed by fine needle aspiration [Figures 4a–d] and biopsy of the lung lesion [Figure 3d], which confirmed the diagnosis of metastatic GCT. Both the pleural fluid and fine needle aspiration cytology smears showed attachment of the osteoclastic giant cells to the cohesive groups of mononuclear stromal cells. This was an important feature that helped in reaching the diagnosis of giant cell tumor. There were no cellular and nuclear pleomorphism, bizarre cells, mitoses, necrosis, or osteoid in both the primary and metastatic tumors, thus the important and common differential of osteogenic sarcoma was excluded. No ancillary studies were performed. The patient was started on chemotherapy. Pulmonary metastases were monitored by a chest CT scan and they were stable for 12 months.

- (a) Microphotographs of FNA smears from lung lesion showing osteoclast giant cells along with a stromal fragment (Pap, 200×); (b) Stromal fragment composed of mononuclear cells, with sticking of osteoclast giant cells (Pap, 400×); (c-d) Osteoclast giant cells along with few inflammatory cells (MGG, 400×)

Giant-cell tumor of the bone is described as the most unpredictable neoplasm of the skeletal system, which can metastasize despite its benign appearance.[78] Although, it was initially regarded as a benign tumor, the potential for metastasis without undergoing sarcomatous transformation was described by Jaffe et al., in 1940.[5] The incidence of lung metastases varies between 1 and 9.1%. Most of the metastases are diagnosed within the first few years. Some of the authors believe that they might not be found after 10 years.[8–10] Solitary metastases to other sites like the regional lymph nodes, scalp, and pelvis have also been documented.[2]

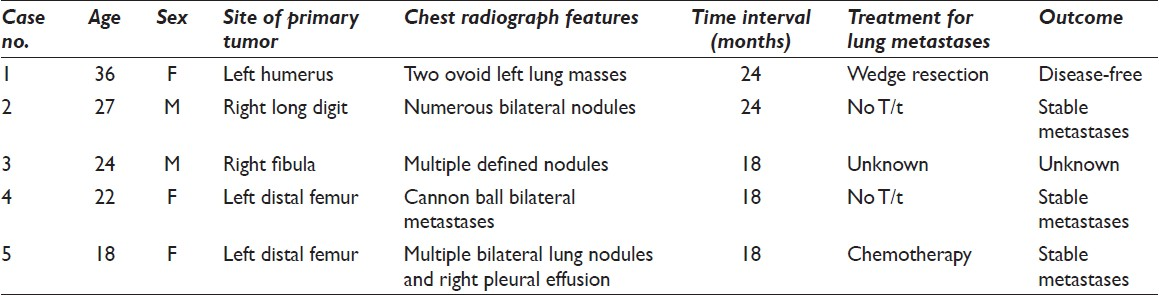

Pulmonary metastasis occurs most frequently in recurrent GCT cases and these tumors have the potential to develop malignant biological behavior.[3] The common primary sites with a predilection for metastasis include, the radius, femur, and sacrum.[578] Radiologically aggressive (Enneking stage III) GCTs are more prone to develop lung metastases.[410] Previously, only four cases of metastatic pulmonary GCT have been diagnosed on aspiration cytology. The details of the reported cases are summarized in Table 1.[11–14] Ours is the fifth case that was diagnosed on pleural effusion and aspiration cytology, and confirmed on biopsy.

The proposed pathogenesis behind the formation of lung nodules in cases of benign GCT includes the proliferation of a subpopulation of neoplastic cells, which has metastatic potential, and origin from the tumor emboli derived from the primary tumor. Mostly, metastatic GCTs are detected a year or more after the initial surgery of the primary lesion. Hemorrhage and thrombus formation occur within the bone, during the operation. Any residual GCT not removed at the time of surgery could grow into this thrombus and then break off, leading to an embolic metastasis in the lungs.[4810] On account of prevalence of the tumor, microemboli at the time of surgery must be greater than the prevalence of metastases, and other biological factors like immune surveillance and intrinsic biological characteristics of the tumor, seem to play a role.[2]

Malignant GCT and giant cellrich osteosarcoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of metastatic GCT on aspiration cytology. In addition, rheumatoid arthritis, herpes infection, granulomatous disease, carcinosarcoma, and mesothelioma with osteoclast-like giant cells, should be excluded by appropriate investigations. A history of GCT of the bone is essential for diagnosis due to the rarity for GCT to present with pulmonary metastasis. When such a history is not available, primary lung carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells should be considered as a differential.[6]

The natural history of the metastasizing lesions is quite variable.[10] They typically progress, although some may ossify peripherally and remain dormant. Rarely, do metastatic lesions of the lung disappear after biopsy.[2] Both the mononuclear and giant cells express CD 68, parathyroid hormone-like protein (PTH-LP), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP). Molecular and cytogenetic abnormalities have been shown to be of potentially prognostic value. The Ki-67 labeling index, p53, and MMP expression are higher in GCTs with pulmonary metastasis, particularly in the aggressive type.[36] Surgical excision of the lung metastases is now the widely accepted treatment of choice, with excellent long-term survival.[9] The role of chemotherapy and radiotherapy is debatable.[1] The mortality rates for patients with a GCT metastasizing to the lungs vary from 0 to 37%.[58]

To conclude, in the aspirate of a lung mass or pleural fluid, the presence of mixed osteoclast-like giant cells and bland mononuclear cells should warrant an inclusion of metastatic GCT in the differential diagnosis, particularly in patients with a positive history. This case report highlights the importance of a plain X-ray of the chest and Computed Tomography scan at the time of the first presentation, even in benign giant cell tumors. Follow-up investigations may be performed, as in primary skeletal sarcomas.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that they qualify for authorship as defined by the ICMJE. All authors are responsible for the conception of this study, have participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is a case report in the form of a letter without patient identifiers, approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) is not required.

EDITORIAL / PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (the authors were blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2012/9/1/22/102864

REFERENCES

- Giant cell tumour of bone with late presentation: Review of treatment and outcome. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2002;10:120-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benign giant-cell tumor of bone with metastasis to mediastinal lymph nodes.A case report of resection facilitated with use of steroids. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:106-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and immunohistochemical characteristics of benign giant cell tumour of bone with pulmonary metastases: Case series. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2004;12:55-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morphological and immunophenotypic features of primary and metastatic giant cell tumour of bone. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:97-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Giant-cell tumour of bone metastasising to the lungs. A long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:43-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary metastasis of giant cell tumor of the bone diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:358-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metastatic giant cell tumor of bone.Are there associated factors and best treatment modalities? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:827-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benign giant-cell tumor of bone with pulmonary metastases: clinical findings and radiologic appearance of metastases in 13 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;158:331-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histologically verified lung metastases in benign giant cell tumours: 14 cases from a single institution. Int Orthop. 2006;30:499-504.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metastases from histologically benign giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:269-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary metastasis from histologically benign giant cell tumor of bone.Report of a case diagnosed by fine needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 1994;38:410-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary metastasis from a benign giant-cell tumor of the hand: Report of a case diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 1996;15:157-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology diagnosis of pulmonary metastasis from giant-cell tumour of bone. Cytopathology. 2002;13:256-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary metastasis of giant cell tumor of the bone diagnosed by fine needle aspiration biopsy. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:358-62.

- [Google Scholar]