Translate this page into:

Detection of rare parasite on Pap smear

*Corresponding author: Dr. Gauravi A. Mishra, MD Department of Preventive Oncology, Tata Memorial Hospital, Room No. 314, 3rd Floor, Service Block, E. Borges Marg, Parel, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. gauravi2005@yahoo.co.in mishraga@tmc.gov.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Anand KV, Mishra GA, Pimple SA, Pathuthara S, Kulkarni VY. Detection of rare parasite on Pap smear. CytoJournal 2020;17:18.

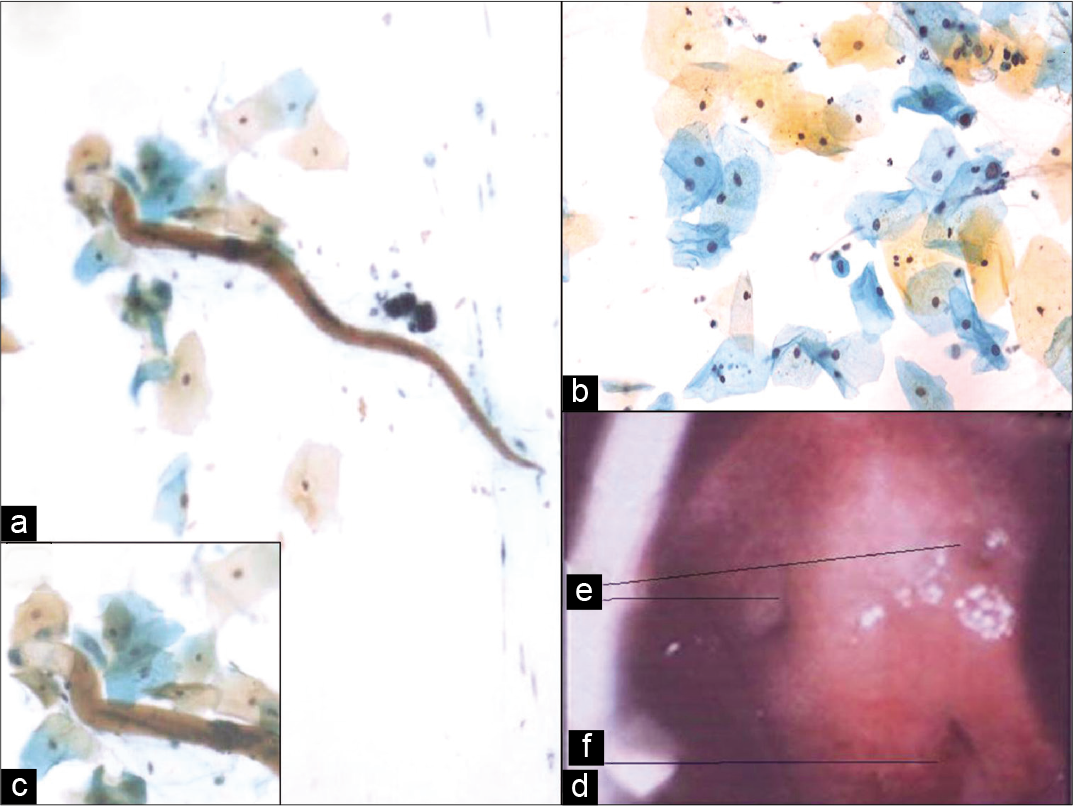

A 49-year-old woman with vague lower abdominal pain on and off for 1 year presented for routine cervical cancer screening at cancer screening department of tertiary care hospital. She underwent a Pap cytology followed by colposcopy examination of the uterine cervix. The Pap cytology picture is shown in Figure 1a-c. On colposcopy, there were two tiny puckered depression marks, each about 1 mm in diameter on the anterior lip [Figure 1d]. The squamocolumnar junction was not visible. No other abnormality was noted on colposcopy.

- (a and b) Pap smear showed many large superficial and intermediate squamous epithelial cells and few squamous metaplastic cells, many neutrophils, some histiocytes, and mixed bacterial flora. A single larval structure with long slender cylindrical body, brownish-yellow cuticle, blunt cephalic end, short yellowish oral cavity, and muscular esophagus (c) with pointed tail noted (Pap ×400). (d) Colposcopy showed two tiny puckered depressions each about 1 mm in diameter, two on the anterior lip (e). External OS (f). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial- Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms. ©2020 Cytopathology Foundation Inc, Published by Scientific Scholar

QUESTION

Identify the parasite

Enterobius vermicularis

Wuchereria bancrofti

Strongyloides stercoralis

Synthetic fiber.

ANSWER

The correct cytological interpretation is

c. Strongyloides stercoralis.

EXPLANATION

The Pap smears were satisfactory for evaluation and showed transformation zone components. Many large superficial, intermediate squamous epithelial cells and few squamous metaplastic cells were identified. Numerous neutrophils, some histiocytes, and mixed bacterial flora were also present. Squamous epithelial cells showed non-specific reactive cellular changes associated with inflammation and bacterial infection. No evidence of intraepithelial lesion or malignancy was identified. In addition, a single rhabditiform larva of Strongyloides stercoralis was detected. The larva appeared to have brownish-yellow cuticle, blunt cephalic end with yellowish oral cavity and esophagus with pointed tail [Figure 1a and c].

DISCUSSION

The estimated global burden of generalized S. stercoralis infection is 30–100 million, whereas the data of prevalence in the Indian population remain unavailable.[1] Due to unreliable and cumbersome tests, it is difficult to diagnose the infection in asymptomatic patients. It is very common for S. stercoralis worm to remain in the infected person without producing symptoms and hence remain undiagnosed for years. Asymptomatic chronic parasitic infection has a potential to develop into disseminated infection thus increasing the morbidity in the infected person. Hence, it is mandatory to systematically investigate and treat the disease. The aim of the present case is to highlight increasing number of cervical S. stercoralis being reported from India, the challenges in establishing the diagnosis and the role of Pap cytology in diagnosis.

Life cycle of Strongyloides

Clinically, it is rare to find S. stercoralis on uterine cervix due to the natural life cycle of the worm. The worm passes its life cycle in one host and unlike other nematodes, a change of the host is not essential. Human is the optimum host for S. stercoralis, although the primary mode of infection is through soil contaminated with larvae. Autoinfection in humans is also known. The female is parthenogenetic and thus can reproduce without male parasite. The filariform larvae penetrate the bare host skin coming in contact with the soil, invade the tissues, and enter the lungs through the right heart via venous blood circulation. From the pulmonary capillaries, larvae enter the alveolar spaces, migrate to bronchi, trachea, larynx, epiglottis and then are swallowed back into the intestinal tract or enter the intestinal tract through the connective tissues where it develops into a full-blown adult worm in small intestine. The females burrow into the mucous membrane and being parthenogenetic, begin to oviposit in the tissues. From the eggs, rhabditiform larvae hatch out and enter the lumen of intestine. Male parasites do not penetrate the mucous membrane and hence are eliminated through feces.

Pathogenicity

The infection with S. stercoralis is known as strongyloidiasis causing skin lesions in the form of urticaria or rash, pulmonary lesions as bronchopneumonia and intractable diarrhea due to intestinal lesions. Marked eosinophilia and moderate leukocytosis may be observed during the invasive stage.

S. stercoralis infection can be a chronic disease of the gut with low parasite load and irregular shedding of larvae. Since majority of patients are asymptomatic or with a vague complaint, it becomes difficult to diagnose and measure the effectiveness of standard treatment imparted and assure complete cure of the disease in the absence of any standard diagnostic tests. The infection may be associated with high or normal eosinophil count during the invasive phase, but this test has limitations.[2] The definite diagnosis would be achieved by stool examination, but stool examination has its limitation in terms of irregular shedding of the worms.[3]

S. stercoralis on uterine cervix forms an incidental diagnosis on Pap smear cytology. It is important to differentiate S. stercoralis from other parasites such as Enterobius vermicularis, Entamoeba histolytica, Paragonimus westermani, or microfilaria. S. stercoralis resembles very closely to hookworm in morphology which forms the immediate differential diagnosis on cytology, but the short buccal cavity is unique of E. vermicularis. S. stercoralis can also be distinguished by the prominent genital primordium and the pointed tail end. The larvae are characterized by cuticle, short oral cavity, long slender cylindrical body, and pointed tail with a “V”-shaped notch. Filariform larvae are longer, thinner and have a long oral cavity compared to rhabditiform larvae, which are thick, curved and with a short oral cavity and muscular esophagus. Filariform larvae can be easily mistaken for hookworm larvae.

In the present case, the woman was retrospectively investigated after the result of Pap cytology. Blood count was within normal limits. Serial stool examinations were done on alternative days, as single stool examination fails to detect larvae in 70% of the cases.[4]

All stool reports were negative for larvae. There was no history of immunodeficiency syndrome. X-ray chest was normal. The possibility of contamination of cytology slides was excluded. The clinical history of walking barefoot on the beach side which may be suggestive of the route of entry of S. stercoralis in the present case was elicited retrospectively. The woman complained of vague abdominal pain which could have been probably related to helminthic infection though sonography of abdomen and pelvis did not reveal any abnormality. The patient was treated with 200 µg/kg ivermectin once daily for 3 consecutive days, considering chronic infection.[2]

At present, available diagnostic tests for S. stercoralis are cumbersome to perform and have varied sensitivity and specificity reported, making it difficult to reach a diagnostic conclusion based on these laboratory tests.[5] The present case highlights the gradual increasing number of S. stercoralis cases being reported on Pap smear.[6-10] Mostly, the cases are asymptomatic and have been reported as an incidental finding on cytology smears among women who presented for routine cervical cancer screening. Recently, a case of S. stercoralis has been reported in cervical biopsy of woman who presented with reproductive tract infection.[11] With the rising case reports of asymptomatic S. stercoralis being reported from India and in the absence of any consensus on the screening and investigation guidelines for the country, it is difficult to clinically manage the cases for an effective cure. The efficacy of standard drugs recommended has not been widely evaluated which again remains challenge in the absence of a diagnostic test.[12]

ADDITIONAL CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION QUESTIONS

-

The larvae of S. stercoralis differ from E. vermicularis in having

Pointed tail

Blunt cephalic end

Long buccal cavity

“V”-shaped notch near tail end.

Answer is d.

-

Primary mode of infection of S. stercoralis is from

Soil contaminated with larvae

Contaminated food

Blood

Drinking water.

Answer is a.

-

Minimum number of hosts required by S. stercoralis to complete life cycle

One

Two

Three

Four.

Answer is a.

-

Rhabditiform larva of S. stercoralis has

Short mouth and muscular esophagus

Long mouth and non-muscular esophagus

Small mouth without esophagus

Long mouth without esophagus.

Answer is a.

SUMMARY

The cytopathologist should be familiar with the morphology of the parasitic larvae and have a high index of suspicion for the timely diagnosis and treatment of subclinical infection. In the absence of any screening and diagnostic test guidelines, the Pap cytology may be the only diagnostic tool.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors and represents honest work.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is case without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from institutional review board (IRB) (or its equivalent).

LIST OF ABBREVIATION (In alphabetic order)

Strongyloides stercoralis – S. stercoralis.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

References

- Soil-transmitted helminth infections: Ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. Lancet. 2006;367:1521-32.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Severe strongyloidiasis: A systematic review of case reports. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:78.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/strongyloides/index.html [Last accessed on 2018 Sep 17]

- Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1040-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strongyloidiasis-the most neglected of the neglected tropical diseases? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:967-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic detection of Enterobius vermicularis and Strongyloides stercoralis in routine cervicovaginal smears and urocytograms. Acta Cytol. 1984;28:468-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic detection of Strongyloides stercoralis in a routine cervicovaginal smear. A case report. Acta Cytol. 1994;38:223-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strongyloides stercoralis as a contaminant in a cervicovaginal smear. Acta Cytol. 2004;48:768-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis in a routine cervical smear. Diagn Cytopathol. 2005;33:31-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serendipitously identified Strongyloides stercoralis in a cervicovaginal smear. J Cytol. 2013;30:270-1.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervical strongyloidiasis in an immunocompetent patient: A clinical surprise. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2015;58:389-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivermectin versus albendazole or thiabendazole for Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;1:CD007745.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]