Translate this page into:

Fine-needle aspiration detects primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast in a patient with breast implants

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Breast augmentation with implantation represents a challenge for subsequent radiographic imaging and pathological sampling. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) is an excellent technique to sample suspicious lesions that are adjacent to fragile implants. We report a case of a 51-year-old woman with breast implants presenting with an initial diagnosis of fibroadenoma by imaging studies. A definite diagnosis of mammary carcinoma with plasmacytoid cells was made on ultrasound (US)-guided FNAB of the breast mass with rapid on-site evaluation which initiated core needle biopsy of the mass and subsequent mastectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy. Our case exemplifies the role of US-guided FNAB for the initial investigation of breast masses in patients with implants. In addition, the case illustrates the cytomorphological features of the tumor cells in primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast.

Keywords

Breast

cytology

fine needle aspiration

implant

neuroendocrine carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Breast augmentation using tissue expanders or implants represents a unique challenge for subsequent radiographic imaging and pathological sampling of suspicious lesions. Despite the improvements in imaging seen with new, more specialized imaging techniques, the radio-opaque nature of implants and their tendency to cause capsular contracture can create shadows that may obscure large portions of the remaining breast parenchyma.[1] The inability to properly compress the breast tissue during mammography in patients with implants also contributes to difficulty in mammographic interpretations and detection of abnormalities in the breast parenchyma.[23] Although breast implants are not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer,[4] optimal visualization of the breast parenchyma by imaging studies may be compromised which may result in the delayed recognition and diagnosis of cancer, thereby contributing to a lower breast cancer survival rate for women with implants.[4]

In patients with breast implants, tumors may arise both in the remainder of the breast parenchyma as well as in the fibrous capsule surrounding the implant.[567] Despite the increasing popularity of core needle biopsy (CNB) for primary breast lesions,[8] fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) of the breast remains a valuable tool for diagnosing lesions adjacent to fragile implants that may rupture if damaged by CNB.

In this report, we describe the important role of ultrasound (US)-guided FNAB of a breast mass in a patient with cosmetic breast implants with rapid on-site assessment that allowed for the definite diagnosis of mammary carcinoma with plasmacytoid features which initiated appropriate clinical management of the patient.

CASE REPORT

A 51-year-old woman presented to our breast clinic with a 2-year history of a self-palpated left breast mass. The patient underwent breast augmentation 12 years earlier with the insertion of bilateral subpectoral saline breast implants which required cosmetic revisions due to malposition and were subsequently positioned subglandularly.

Breast imaging by mammography and ultrasonography revealed a 0.8-cm well-defined mass which was radiographically reported to be consistent with fibroadenoma at an outside institution. She refrained from 6-month surveillance scans until she noticed an increase in size of the mass. Despite its reported benign appearing nature on imaging, the patient desired removal of the lesion.

Prior to excision, a repeat US and US-guided FNAB were performed by a radiologist, and immediate assessment for specimen adequacy was performed by the cytopathologist. Direct smears were made from the aspirated material and fixed in Carnoy's solution for Papanicolaou staining and also air-dried for Diff-Quik staining. The syringe used for the aspiration was rinsed in Roswell Park Memorial Institute solution which was centrifuged. The cell pellet that was generated was sufficient to prepare a single cytospin which was stained by Papanicolaou method.

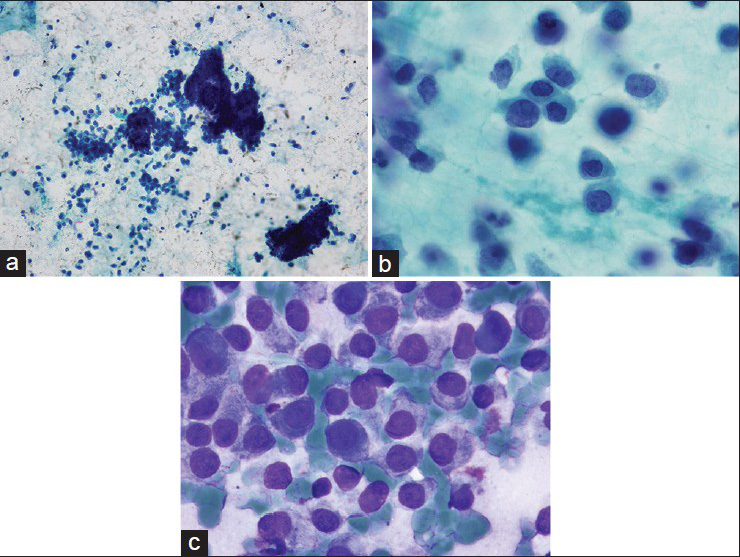

The FNAB smears showed high cellularity with many dispersed single intact atypical epithelial cells and very few loose clusters. The epithelial cells exhibited a striking plasmacytoid appearance with a moderate amount of granular eosinophilic cytoplasm. The nuclear chromatin of the cells was fine without conspicuous nucleolus. Rare mitotic figures were identified. There was no evidence of mucin vacuoles in the atypical cells. Naked bipolar nuclei were absent in the background of the smears. The overall cytomorphological findings were consistent with a well- to moderately-differentiated mammary carcinoma with plasmacytoid features, raising concern for a neuroendocrine carcinoma [Figure 1]. Due to the lack of cell block material from the FNAB, a CNB was subsequently performed under US guidance [Figure 2].

- Fine-needle aspiration smears show increased cellularity with mostly single, dispersed cells and occasional larger clusters of plasmacytoid cells. The nuclei are relatively monomorphic, eccentrically placed and have fine nuclear chromatin. (a, b) Pap smear. (c) Diff-Quik

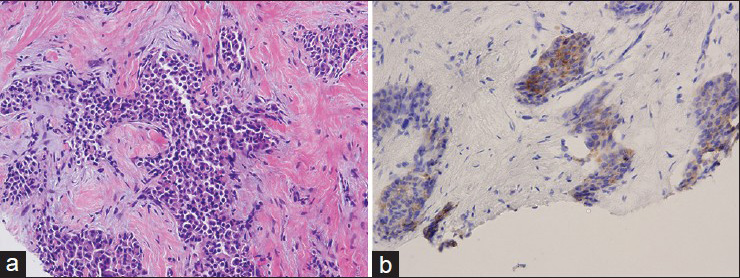

- Invasive carcinoma comprised of plasmacytoid tumor cells, is seen on hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue sections of the core needle biopsy (a). The tumor cells are immunopositive for synaptophysin which supports the diagnosis of neuroendocrine carcinoma (b)

Ancillary testing on the CNB showed that the tumor was positive for estrogen receptor (30% of tumor cells; moderate intensity) and progesterone receptor (90% of tumor cells; strong intensity) and negative for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2/neu) protein overexpression (1 + staining in 10% of tumor cells). The tumor cells expressed synaptophysin (90% of cells) and chromogranin (50% of cells) while negative for CDX-2. The tumor was classified as invasive ductal carcinoma with features consistent with primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast based on the FNAB and CNB findings.

The patient underwent bilateral total mastectomies with sentinel lymph node dissection. Histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of invasive neuroendocrine carcinoma, intermediate nuclear grade, and Nottingham histologic grade 2. The invasive tumor demonstrated small areas of extracellular mucin. Focal lymphovascular invasion was identified, and isolated tumor cells were found to be present in one sentinel lymph node upon keratin immunohistochemical analysis.

DISCUSSION

Despite the increasing popularity of CNB for primary breast lesions, FNAB of the breast remains, a valuable tool in selected patients for the investigation of breast lesions. One such application is the initial investigation of palpable or nonpalpable breast masses in women with breast implants. Implants are radio-opaque and may cause capsular contracture that create shadows and obscure large portions of the breast parenchyma during imaging.[1] The breast tissue is difficult to compress during mammography in patients with implants which poses challenges to accurate mammographic interpretations and detection of abnormalities. The patient in this report received an accurate diagnosis of mammary carcinoma through the use of FNAB for a mass that was previously considered to be fibroadenoma based on imaging studies alone. The ability to more easily manipulate the needle and the lower probability of rupturing the implant while performing the biopsy allows FNAB to be utilized in the investigation of breast masses with implants.

Cytologically, the categorization of this breast lesion as malignant was evident in our case due to the presence of highly cellular smears comprised of a single population of plasmacytoid epithelial cells which raised the possibility of neuroendocrine carcinoma.[91011] Ancillary immunostains for neuroendocrine differentiation including markers such as chromogranin and synaptophysin are the most useful to establish a definitive diagnosis, especially if cell block material is available. Cases in which CNB is difficult to perform due to the presence of implants may utilize FNAB and cell block preparation for immunostaining in order to establish the diagnosis. Our case was challenging in both the clinical presentation of the mass in a patient with breast implants and in establishing the diagnosis of a rare primary breast neuroendocrine carcinoma.

Neuroendocrine carcinomas involving breast can be primary mammary carcinomas with neuroendocrine differentiation or metastatic neuroendocrine tumors from primary sites such as gastrointestinal tract or lung. The majority of neuroendocrine tumors are metastatic to the breast from gastrointestinal tract and lung.[121314] The primary location of a neuroendocrine tumor can be determined through an immunohistochemical panel encompassing CDX-2, thyroid transcription factor 1, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, mammaglobin, and GATA-3.[1415]

The biologic behavior of solid neuroendocrine tumors is not entirely certain owing to is the rarity and limited documentation of these tumors in the literature.[1617] In correlation with their low nuclear grade, the majority of reports demonstrate an improved or similar outcome compared to invasive ductal carcinoma.[18192021] However, the largest case series studying 74 neuroendocrine carcinomas in the breast demonstrated a worse clinical outcome, as measured through overall survival and distant recurrence-free survival, compared with invasive mammary carcinoma with similar pathologic stage, and matched for HER2/neu status as well as age, sex, and race.[2223]

There are no specific radiological features of primary neuroendocrine tumors of the breast, although they are commonly mistaken for fibroadenomas or cysts, as was the case with this patient.[12] Recognition of the cytomorphological and immunophenotypic features and distinction of the tumor from other mimics is important for accurate diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

Our case exemplifies the role of FNAB for the diagnosis of breast masses associated with implants even in today's era, where CNB is very often used for preoperative diagnosis, especially in challenging cases like patients with breast implants. In this case report, US-guided FNAB of a palpable breast mass in a patient with breast implants with immediate on-site evaluation was successful in rendering a diagnosis of a rare primary mammary neuroendocrine carcinoma which initiated appropriate clinical management.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author.

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

JIM conceived the study, acquired the data, and drafted the manuscript. UK conceived the study and acquired data. LS acquired the data. SK conceived the study, acquired data and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is a case report without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) (or its equivalent). Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Breast implants and breast cancer screening. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2003;48:329-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting mammographic visualization of the breast after augmentation mammaplasty. JAMA. 1992;268:1913-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Breast cancer diagnosis in women with subglandular silicone gel-filled augmentation implants. Radiology. 1995;194:859-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Breast cancer detection and survival among women with cosmetic breast implants: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2013;29(346):f2399.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anaplastic large cell lymphoma arising in a silicone breast implant capsule: A case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:e115-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary breast lymphoma in a patient with silicone breast implants: A case report and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:822-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Obituary: “Alas poor FNA of breast-we knew thee well!”. Diagn Cytopathol. 2005;32:1-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic cytological features of neuroendocrine differentiated carcinoma of the breast. Virchows Arch. 1998;433:217-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of a male breast carcinoma exhibiting neuroendocrine differentiation.Report of a case with immunohistochemical, flow cytometric and ultrastructural analysis. Acta Cytol. 1995;39:803-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration of mammary carcinoma with features of a carcinoid tumor. A case report with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies. Acta Cytol. 1994;38:73-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuroendocrine ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: Cytological features in 32 cases. Cytopathology. 2011;22:43-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metastatic neuroendocrine tumour in the breast: A potential mimic of in-situ and invasive mammary carcinoma. Histopathology. 2011;59:619-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solid neuroendocrine carcinomas of the breast: Metastases or primary tumors? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124:413-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Breast carcinoma – Rare types: Review of the literature. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1763-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast with a mucinous carcinoma component: A case report with review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2012;4:29-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuroendocrine differentiated carcinomas of the breast: A distinct entity. Breast. 2003;12:251-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solid neuroendocrine breast carcinomas: Incidence, clinico-pathological features and immunohistochemical profiling. Oncol Rep. 2008;20:1369-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tissue microarray analysis of neuroendocrine differentiation and its prognostic significance in breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1001-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic significance of tumor grading and staging in mammary carcinomas with neuroendocrine differentiation. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:1169-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Invasive neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast: A distinctive subtype of aggressive mammary carcinoma. Cancer. 2010;1(116):4463-73.

- [Google Scholar]