Translate this page into:

Human Immunodeficiency Virus-associated primary effusion lymphoma: An exceedingly rare entity in cerebrospinal fluid

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) in patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection may involve pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal cavities. PEL involving the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is exceedingly rare, and to our knowledge has only been reported in two cases. We report another case of PEL diagnosed in CSF from a 61-year-old male with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome that presented with neurological symptoms. Imaging studies of his brain showed leptomeningeal/periventricular enhancement, but no mass lesion. His CSF demonstrated human herpesvirus-8 positive pleomorphic lymphoplasmacytoid cells of null cell phenotype. This case highlights that albeit rare, PEL should be included in the differential diagnosis when large atypical cells are encountered in CSF of HIV-positive patients, even when such patients have no history of lymphoma. As in this case, ancillary studies are required to make an accurate diagnosis of PEL in CSF cytology.

Keywords

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

cerebrospinal fluid

cytopathology

human herpesvirus-8

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

primary effusion lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is a large cell lymphoma that presents as a serous effusion without a detectable tumor mass.[12] The majority of cases occur in young males with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection and severe immunodeficiency. The most common sites of involvement are pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal cavities. These lymphomas are positive for Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus/human herpesvirus-8 (HHV8).[34] Coexistent Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) positivity may be seen in the majority of cases. However, HHV8 rather than EBV is the driving force in this lymphoma.[5] PEL tends to occur as a late manifestation of HIV, which helps to explain why these lymphomas have such a poor prognosis. The diagnosis of PEL typically rests on supportive cytology and confirmatory ancillary studies of a lymphomatous effusion.

PEL involving the subarachnoid space is exceedingly rare. To our knowledge, only two such cases have been previously reported.[67] Herein, we describe another case of PEL involving the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in a HIV positive patient. This case is being reported to highlight the importance of keeping PEL in the differential diagnosis when large cells are seen on CSF cytology, especially in immunosuppressed patients.

CASE REPORT

Clinical findings

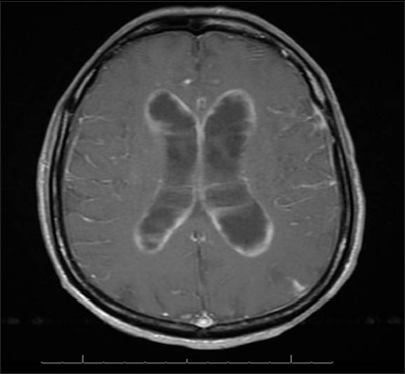

A 61-year-old male with a history of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) presented with hallucinations, confusion, urinary incontinence, and an unsteady gait. He also complained of bilateral lower extremity weakness developing over several weeks. He had HIV for over 20 years and was treated with efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir. He had no prior history of lymphoma or tumors. His CD4 count was 16 cells/mm3 and HIV viral load below 40 copies/mL. He was afebrile, had lipodystrophy and no lymphadenopathy. A computed tomography scan of his head showed an enlarged ventricular system with a small amount of intraventricular blood. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed findings suggestive of multiple prior subarachnoid hemorrhage, hydrocephalous as well as diffuse leptomeningeal and ependymal enhancement [Figure 1]. A lumbar puncture was performed and sent for diagnostic evaluation. His CSF had 94% lymphocytes, 6% monocytes, and no red blood cells. After a diagnosis of PEL involving the CSF was made, the patient was discharged with home hospice.

- Brain magnetic resonance image showing leptomeningeal/periventricular enhancement, but no mass lesion

Cytopathology findings

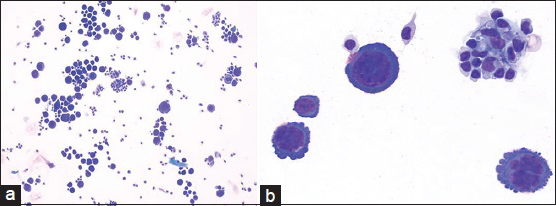

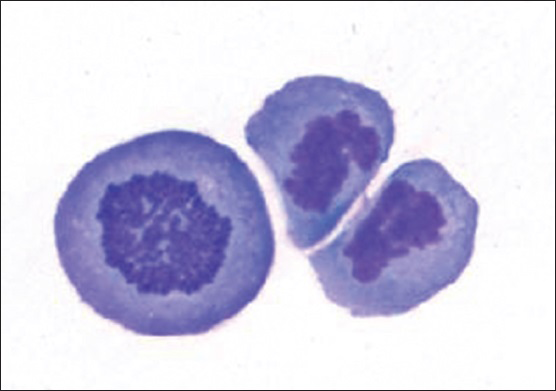

Cytologic evaluation of the CSF with ThinPrep (Pap stain) and cytospin (DQ stain) preparations demonstrated the presence of several large malignant cells [Figure 2]. These cells had a moderate amount of deeply basophilic cytoplasm and occasional small peripheral vacuoles. They had a high nuclear: cytoplasmic ratio, pleomorphic nuclei with irregular contours, and distinct nucleoli. Mitotic figures were apparent in many of these large cells [Figure 3]. There were also a few small mature lymphocytes and reactive monocytes in the background.

- (a) Cerebrospinal fluid containing large lymphoma cells (DQ stain; ×200). (b) Primary effusion lymphoma cells with pleomorphic nuclei and smaller background lymphocytes and monocytes (DQ stain; ×600)

- Actively dividing primary effusion lymphoma cells (DQ stain; original magnification ×600)

Ancillary study results

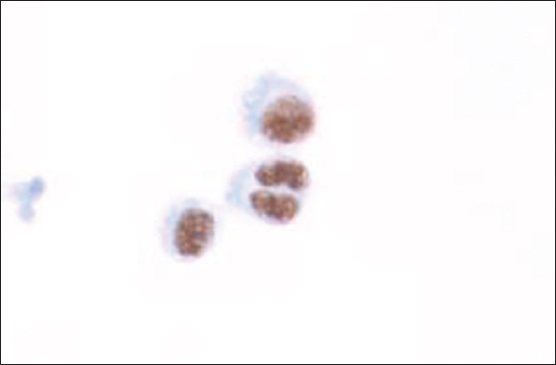

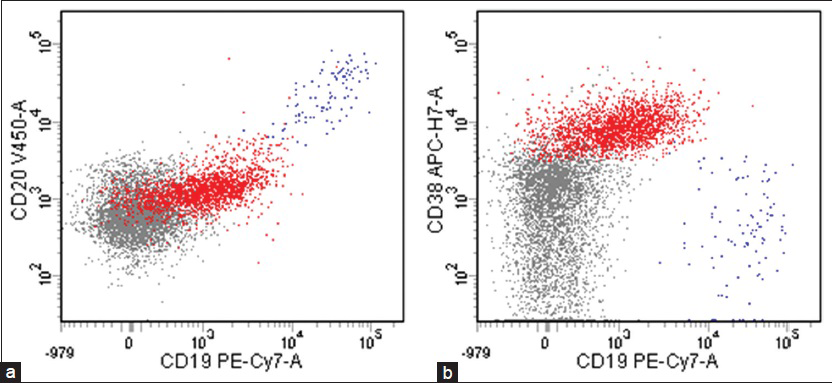

Flow cytometric analysis demonstrated that the large cells (2.1% of the total population) were CD20 negative, CD19 dim positive, and CD38 positive [Figure 4], but were insufficient for definite characterization of light chain expression. Immunocytochemical stains performed on additional cytospins showed that the large cells were weakly positive for leukocyte common antigen and negative for pankeratin, CK7, CK20, and TTF-1. An immunostain for LNA-1 (HHV8) was positive in the large cells [Figure 5]. There was insufficient sample to attempt in-situ hybridization for EBV-encoded small RNA. These results confirmed the diagnosis of PEL involving the patient's CSF.

- Cytospin showing LNA-1 (human herpesvirus-8) positive tumor cells (immunocytochemistry; ×400)

- Flow cytometric analysis showing that large lymphocytes (red), 2.1% of the total population, were (a) CD20 negative, CD19 dim positive, and (b) CD38 positive (blue: B-cells, grey: Other lymphoid cells including T-cells and NK-cells)

DISCUSSION

PEL, previously referred to as body cavity-based lymphoma, was first introduced by Nador et al. in 1996, as a separate entity to distinguish it from other malignant lymphomas that secondarily involve body cavities.[3] By definition, there is usually no tumor mass, lymphadenopathy, or organomegaly present. Although PEL tends to remain localized to the body cavity of origin, tissue extension of lymphoma into the pleura, lung, chest wall, peritoneum, omentum, and gastrointestinal tract may rarely occur.[8] Morphologically, PEL cells can exhibit a range of appearances.[910] Lymphoma cells can show large immunoblastic, plasmablastic to anaplastic morphology. The nuclei of these lymphoid or lymphoplasmacytoid cells, as demonstrated in our case, tend to be large and irregular in shape, and have prominent nucleoli. They have abundant, deeply basophilic cytoplasm, sometimes with vacuoles. Some cells may even resemble Reed-Sternberg cells. These malignant features can also be seen with high-grade metastatic tumors (e.g., carcinoma or melanoma), as well as with lymphomas secondarily involving the body cavities.

Many PEL cases often have a null cell phenotype by flow cytometric evaluation, which may make them challenging to distinguish from nonhematopoietic tumors. They are CD45 positive, but are negative for pan-B-cell markers including CD19, CD20, and CD79a as well as surface and cytoplasmic immunoglobulins. They are negative for T/NK-cell markers, but may show aberrant expression. Plasma cell-related markers (e.g. CD38) and a variety of non-lineage associated antigens such as HLA-DR, CD30, and even EMA may be positive.[11] As in our case, HHV8 positivity is very useful in differentiating PEL from non-Hodgkin lymphoma secondarily involving body cavities. The majority of HHV8 negative effusion lymphomas occur in HIV-negative elderly patients.[12] Failure of these tumor cells to stain with keratin or melanoma markers and immunoreactivity for HHV8 helps differentiate PEL from metastasis.

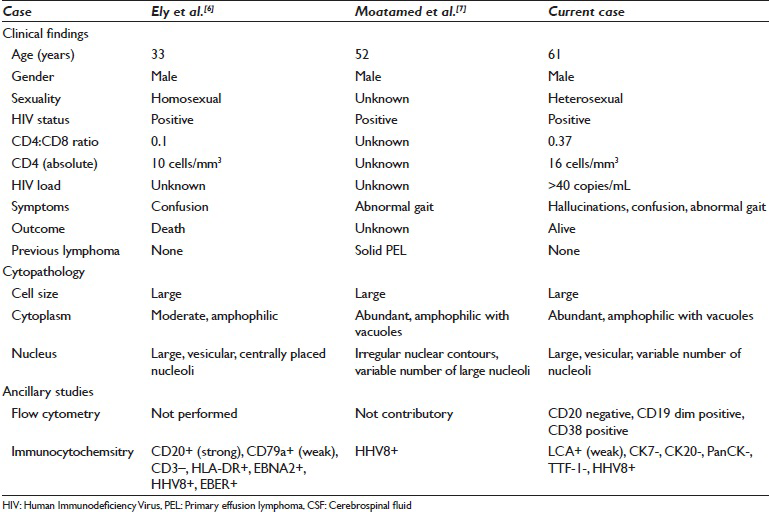

PEL has a unique tropism for serous cavities of the body (viz. pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal effusions). PEL involving CSF is exceedingly rare. Table 1 compares the clinical-pathologic findings in the two other similar reported cases. Ely et al. described a case of PEL in the subarachnoid space of a homosexual man with AIDS without an associated tumor mass.[6] Moatamed et al. also described a case of PEL in the CSF in an HIV positive patient who had a past history of HHV8 positive solid variant of PEL lymphoma of the right inguinal lymph node diagnosed a year before the CSF was diagnosed.[7] While CSF in HIV infected patients may harbor EBV, it is unusual to detect HHV8 in CSF. When Brink et al. studied CSF supernatant in 115 HIV infected patients HHV8 DNA was detected only in 2 patients, only one of whom had (systemic, but not CNS) lymphoma.[13]

In summary, this case highlights that albeit very rare, PEL should be included in the differential diagnosis when large atypical cells are encountered in CSF of HIV-positive patients. Ancillary studies including flow cytometry and LNA-1 immunocytochemistry are required to make an accurate and definitive diagnosis of PEL in CSF.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors declare no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that they qualify for authorship as defined by the ICMJE. All authors are responsible for the conception of this study, have participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the institution.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

AIDS - Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

CSF - Cerebrospinal Fluid

EBV - Epstein-Barr Virus

HHV8 - Herpesvirus/Human Herpesvirus-8

HIV - Human Immunodeficiency Virus

IRB - Institutional Review Board

PEL - Primary Effusion Lymphoma

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2015/12/1/22/168059

REFERENCES

- Primary effusion lymphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. p. :260-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma: A distinct clinicopathologic entity associated with the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes virus. Blood. 1996;88:645-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro establishment and characterization of two Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome-related lymphoma cell lines (BC-1 and BC-2) containing Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like (KSHV) DNA sequences. Blood. 1995;86:2708-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV/AIDS: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus disease: Kaposi sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1209-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-positive primary effusion lymphoma arising in the subarachnoid space. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:981-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma involving the cerebrospinal fluid. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:635-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Still a problem in the era of HAART. AIDS Read. 2004;14:605-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma: A series of 4 cases and review of the literature with emphasis on cytomorphologic and immunocytochemical differential diagnosis. Cancer Cytopathol. 2007;111:224-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- HHV8-negative effusion based lymphoma: A series of 17 cases at a single institution. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2015;4:37-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of Epstein-Barr virus and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus DNA in CSF from persons infected with HIV who had neurological disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:191-5.

- [Google Scholar]