Translate this page into:

Hyperchromatic-crowded groups (HCG) in pap smears

*Corresponding author: Evi Abada, MD, MS Detroit Medical Center, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan, USA. evi.abada@wayne.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Abada E, George K, Shidham V. Hyperchromatic- crowded groups (HCG) in pap smears. CytoJournal 2020;17:17.

A 30-year-old female presented to the hospital for routine gynecological evaluation, and a ThinPrep Pap test was performed. She had regular menses but with a “heavy flow.” She also stated that her cervix had been described as “friable” on prior regular gynecologic examinations.

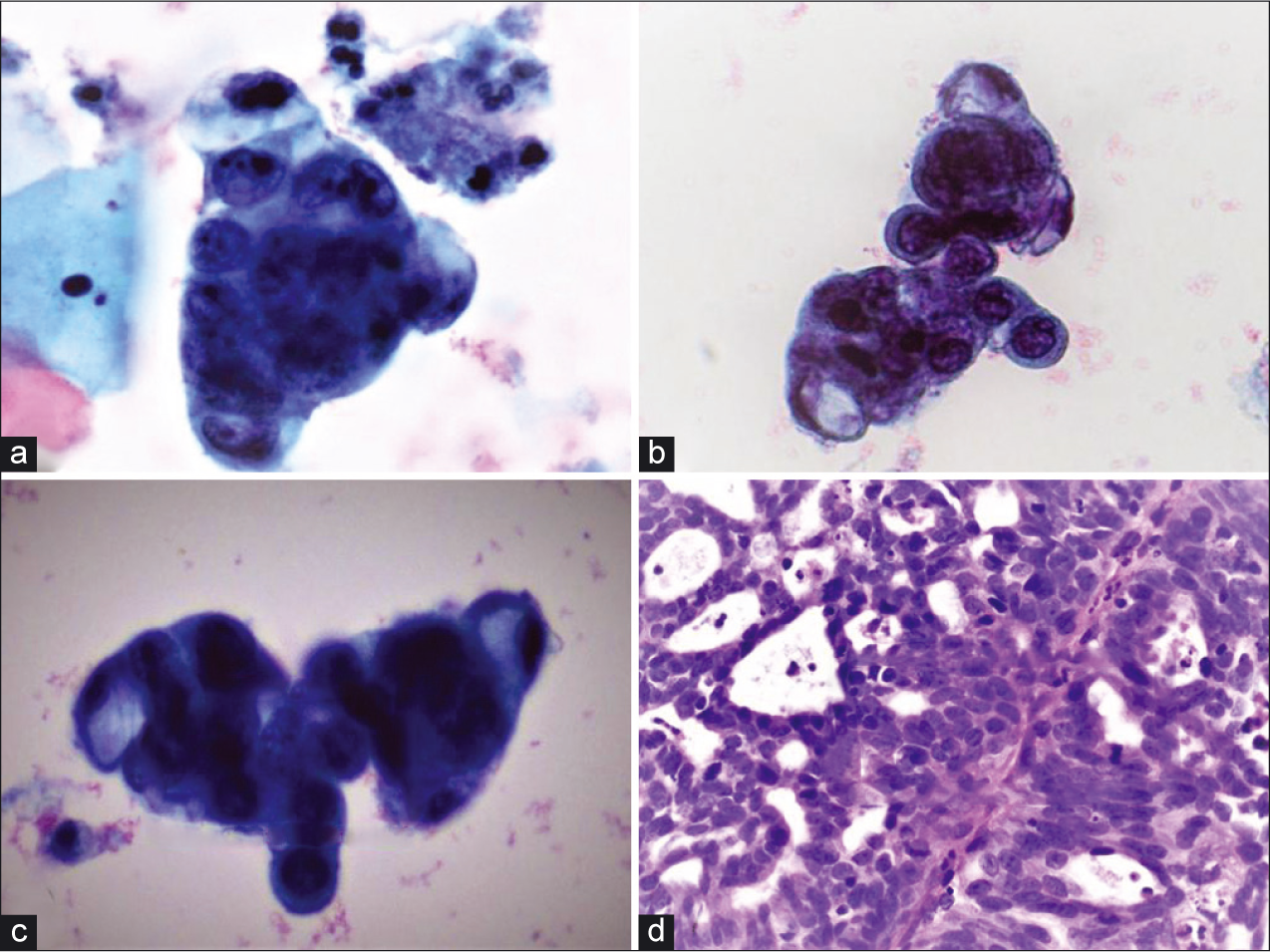

ThinPrep Pap test revealed hyperchromatic-crowded groups (HCG) with cytomorphology as seen in Figure 1.

- Hyperchromatic-crowded groups (a and b) adjacent to benign squamous cells (PAP, ×40), (c) hyperchromatic-crowded group with intracytoplasmic mucin (PAP, ×40), (d) The biopsy specimen showed cribriform/microacinar architecture with confluent neoplastic glands (H and E, ×40).

QUESTION 1: WHAT IS YOUR INTERPRETATION?

Microglandular hyperplasia (MGH)

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS)

Arias Stella reaction

Atypical glandular cells, not otherwise specified (AGC-NOS)

Cervicitis/reactive endocervical cells.

Answer to question 1: Option D (AGC-NOS).

EXPLANATION

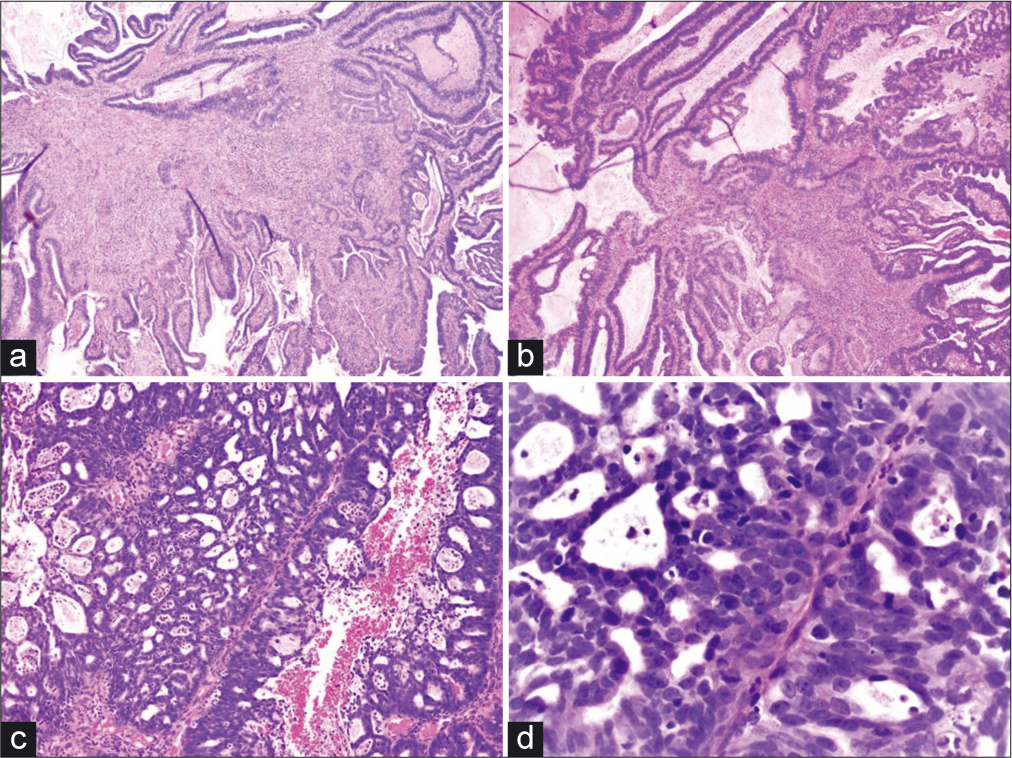

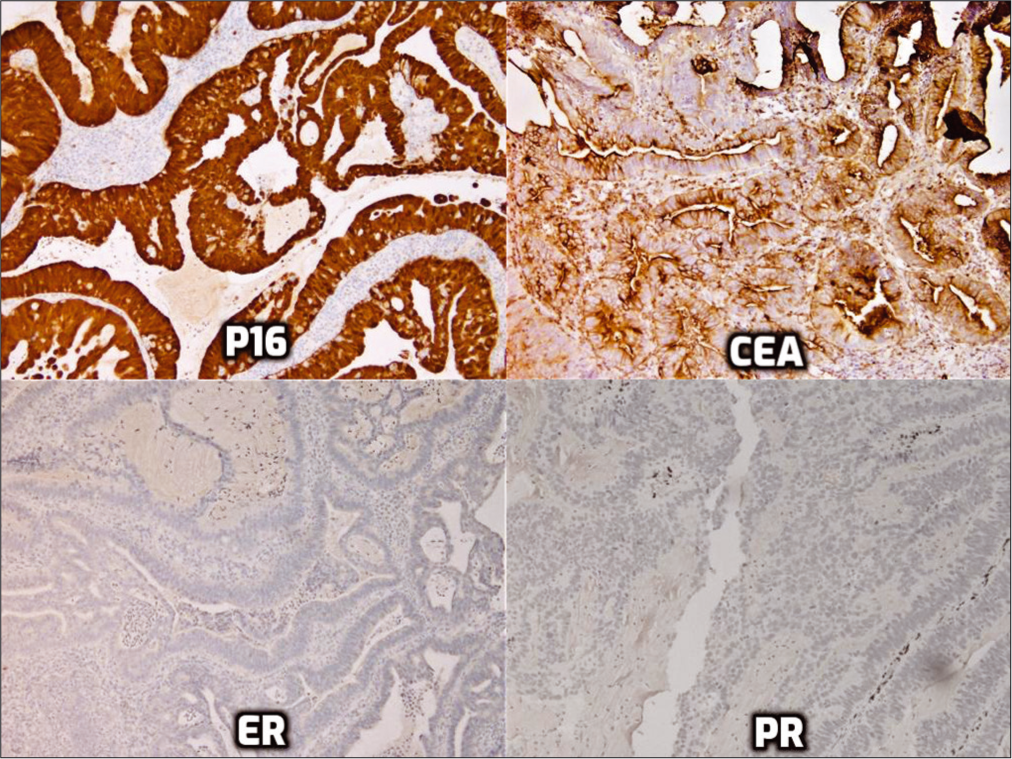

Pap smear showed HCG with focal pseudorosette formation. The cells showed high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratios, hyperchromatic nuclei with coarse chromatin, nuclear membrane irregularities, ill-defined cell borders, and prominent nucleoli [Figure 1]. Some cells also showed intracytoplasmic mucin. Mitoses or apoptotic debris were not detectable. Although this patient is young and has a previous history of cervicitis, the degree of cytologic atypia seen in this Pap test definitely exceeds reactive or reparative changes and warrants interpretation as AGC. Although the cytomorphology suggests endocervical differentiation, the exact site cannot be decided as they may originate from the endocervix, endometrium, or other Mullerian sites, which necessitates further diagnostic evaluation with interpretation as AGC-NOS. MGH (option A) is often seen as an incidental, polypoid, nonneoplastic proliferation of endocervical cells in reproductive-aged women. It is characterized by uniform glandular cells with dense-to-vacuolated cytoplasm, uniform small nuclei, and the presence of plasma cells and acute inflammatory cells.[1] The glandular spectrum of HCG from MGH may also display mild cytologic atypia with nuclear enlargement and hyperchromasia.[2] The cells may have multiple nucleoli, mitotic figures, and apoptotic bodies (normoblast- like apoptosis in squamous metaplastic cells).[1,2] AIS (option B), which is typically asymptomatic, demonstrates a different cytologic spectrum. AIS displays crowded sheets of stratified and enlarged cigar-shaped glandular cells with hyperchromatic nuclei with coarse chromatin, relatively inconspicuous nucleoli, mitoses, particularly in an apical location, and apoptotic bodies.[3] In addition, the nuclei may show partial denudation which confers a feathering appearance. Arias-Stella (AS) reaction (option C) is a nonneoplastic process with human chorionic gonadotropin production usually associated with pregnancy, postpartum period, oral contraceptive (OCP) use, or gestational trophoblastic disease. AS cells are characterized by large, pleomorphic cells with nuclear crowding and overlapping. Occasionally, the nucleoli are multiple. The cytoplasm varies from scant to abundant, often contains vacuoles, and has been reported as showing variable staining characteristics varying from pale to dark. The nuclei have a granular to coarse chromatin pattern with ground-glass to smudgy appearance.[4] Interpretation as cervicitis/reactive endocervical cells (option E) was ruled out due to the degree of cytologic atypia which was unequivocally more significant than what would be expected in reactive endocervical cells as seen in HCG.[2] High-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) test was positive in this patient, and endocervical curettage with cervical biopsy revealed the findings shown in Figure 2. The tumor cells showed nuclear immunoreactivity for p16 with monoclonal carcinoembryonic antigen (mCEA) immunoreactivity but nonimmunoreactivity for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and vimentin [Figure 3].

- (a and b) Angulated, fragmented, infiltrative, and irregularly shaped glands with a conspicuous desmoplastic reaction (H and E, ×4 and ×10). (c and d) Malignant fused glands with cribriform architecture and a neutrophilic infiltrate (H and E, ×10 and ×40).

- Immunohistochemistry for p16, monoclonal carcinoembryonic antigen, estrogen receptor, and progesterone receptor.

ADDITIONAL QUIZ QUESTIONS

Question 2: What is your final interpretation?

AIS

Invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma (ADC)

Invasive endometrioid ADC

Metastatic ADC

MGH

Answer to Question 2: Option B, invasive endocervical ADC.

EXPLANATION

The biopsy specimen showed cribriform/microacinar architecture with confluent neoplastic glands with stromal invasion and neutrophilic infiltrate with foci of nonneoplastic endocervical mucosa. The atypical glands were irregularly shaped, fragmented, and angulated with a conspicuous desmoplastic reaction. Mitotic activity was present. The tumor showed nuclear and cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for p16, immunoreactivity for mCEA,[5] and nonimmunoreactivity for ER, PR, and vimentin confirming the diagnosis of invasive endocervical ADC. Option A, AIS, shows epithelial cell crowding with or without stratification, nuclear enlargement with hyperchromasia, coarse chromatin without prominent nucleoli, presence of mitotic figures, and conspicuous architectural alteration including papillary or cribriform intraglandular growth. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is comparable to that for invasive endocervical ADC; however, in AIS, the glandular-stromal interface is well maintained[6] without invasion, unlike what was seen in the current patient. Option C, endometrioid ADC, often shows back-to-back glands lined by cells with varying degrees of atypia with focal benign squamous elements with stromal foamy histiocytes. The tumor cells show scant cytoplasm and nuclei with vesicular chromatin without prominent nuclear pseudostratification. Endometrial endometrioid ADC is often ER, PR, and vimentin immunoreactive, while usually nonimmunoreactive for mCEA and p16,[3] unlike what was seen in the current case. Option D, metastatic ADC, may present with a clinical history of a known primary disease, significant angiolymphatic invasion, and more extensive immunohistochemical stains may be needed to evaluate for unknown primary. Option E, MGH, is often seen as an incidental finding in reproductive- aged women associated with OCP use or pregnancy. It is usually superficially located and consists of closely packed glands lined by low columnar or cuboidal cells with lumina containing mucin and inflammatory cells, particularly polymorphonuclear leukocytes.[7] The cells frequently display subnuclear or supranuclear vacuoles, small uniform nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, absent to rare mitotic figures, and focal squamous metaplasia. The cells may show focal immunoreactivity for p16, especially in areas with squamous metaplasia; however, mCEA and vimentin are often negative.[3]

Brief review of the topic

The frequency of endocervical ADC among all cervical neoplasias has increased in the last decades, from <10% to up to 27%, not only due to a real increase in annual incidence but also due to a decrease in frequency of invasive squamous cell carcinoma.[3] There are several subtypes, and these include (a) usual endocervical ADC, including well-differentiated villoglandular papillary ADC, (b) endometrioid, including minimal deviation endometrioid ADC, (c) mucinous, including gastric, minimal deviation mucinous, intestinal, and signet ring cell ADC, (d) clear cell, (e) serous, and (f) mesonephric ADC.[3]

Of the various histological subtypes of endocervical ADC, usual endocervical type is the most common, accounting for about 75% of all cervical ADCs.[8] Among usual endocervical type tumors, HPV DNA is identified in 80%–100% of cases, with HPV 16 and 18 accounting for about 95%.[8,9] HPV 18 alone actually accounts for about 50% of endocervical ADC.[10] Patient ages range from 22 to 80 years, with an average of 45.[8,9] Similar to squamous cell carcinoma, early cervical ADC is usually asymptomatic and most commonly detected through cervical cytology cancer screening, which is primarily the screening method for cervical squamous cell lesions. However, symptomatic cases may present with dyspareunia, postcoital bleeding, abnormal vaginal bleeding including menorrhagia and metrorrhagia, postmenopausal bleeding, and abnormal vaginal discharge. In addition, a cervical mass may be detected on pelvic examination performed for another indication.[11]

Cervical cytology preparations may show HCG with atypical features suggestive of malignancy including sheets and strips with nuclear crowding, overlap and/or pseudostratification, rare cell groups with rosettes (gland formations) or feathering, enlarged and elongated nuclei with hyperchromasia, coarse chromatin with heterogeneity, occasional mitoses and/or apoptotic debris, cells with increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, and ill-defined cell borders.[12] The tumor cells usually show abundant intracytoplasmic mucin which may be scant and focal in some cases.[13]

HCG were first described by DeMay in 1995 and are a frequent occurrence in Pap tests.[2] Benign glandular cell HCG are seen far more frequently than either abnormal glandular cell HCG or squamous cell HCG in routine Pap tests.[2] Benign endometrial cells may also present as HCG in Pap tests, as small, crowded cells, with degenerate and hyperchromatic nuclei.[2] Mitotic figures are typically not seen in exfoliated cells but may be seen in directly sampled cells. One of the most important abnormal glandular causes of HCG is endocervical neoplasia, including both AIS and invasive ADC.[2] In addition, endometrial ADC may also present as HCG. The other most clinically significant differential diagnosis with HCG is that of a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (CIN2/3), with or without involvement of endocervical glands.[2] Therefore, a careful scrutiny of HCGs on Pap tests is mandatory to prevent a false-positive diagnosis.[2]

Endocervical-type ADC in cervical biopsy exhibits a variety of architectural patterns ranging from well differentiated to poorly differentiated.[13] The well-differentiated tumors may show exophytic papillary growth, infiltrative growth, or both. The invasive tumor may be composed of irregular cystic and tubular glands, glands with intraluminal papillary infoldings, or cribriform glands.[13] In moderately differentiated tumors, the growth is more confluent with sheets of small cribriform glands, and poorly differentiated ADCs show solid areas of undifferentiated cells that may be undistinguishable from poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.[13]

On IHC, endocervical-type ADC demonstrates strong and diffuse nuclear (and cytoplasmic) immunoreactivity for p16, cytoplasmic and membranous immunoreactivity for mCEA, and strong-to-weak nuclear immunoreactivity for PAX8.[13]

The tumor cells are nonimmunoreactive for PR and vimentin, with negative to weak positivity for ER.[13] Finally, the Ki-67 index usually exceeds 25%, with an average of 53%, indicating high proliferation activity in the tumor cells.[14] Invasive endocervical-type ADC is treated with a combination of surgery, radiation therapy, and/or chemotherapy depending on the stage. Prognosis depends on a variety of factors including stage, nodal status, tumor volume, depth of cervical stromal invasion, lymphovascular invasion, and grade. However, in general, cervical ADC tends to carry a worse prognosis than squamous cell carcinoma.[11] Important treatment considerations include the preservation of fertility when possible, especially among younger patients. Unfortunately, because cervical ADCs tend to be multifocal, there is a greater concern for residual disease than with squamous cell carcinoma.[11] Consequently, in making management decisions, the clinical team must decide whether preservation of fertility is the safest and best option for the patient.

Q3. Which of the following HPV genotypes account for about 50% of cervical ADC cases?

HPV 16

HPV 18

HPV 31

HPV 33.

HPV 18 infection accounts for approximately 50% of cervical ADC cases.[10]

Q4. Which of the following is not a risk factor for cervical ADC?

HPV 16 infection

HPV 18 infection

Cigarette smoking

Oral contraception use

Overweight/obesity.

While cigarette smoking is a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma, it does not appear to increase the risk of cervical ADC.[15] All other risk factors listed have positive associations with cervical ADC, although there is some discussion on whether lower rates of screening contribute to increased risk of cervical ADC among overweight/obese women.[16,17]

Q5. Which of the following patterns of invasion are associated with the greatest risk of lymph node metastases?

Pattern A (Well-demarcated glands without destructive stromal invasion)

Pattern B (Early destructive stromal invasion arising from well-demarcated glands)

Pattern C (Diffuse destructive invasion with solid or confluent architecture).

Pattern C is described as a diffuse, destructive invasion. Tumors of this pattern carry a 23.8% risk of lymph node metastases. Pattern B consists of early destructive stromal invasion by well-demarcated glands and has a 4.4% risk of lymph node metastasis. Finally, pattern A involves well to moderately differentiated ADC containing well-demarcated glands with intraglandular growth, but no desmoplastic stromal reaction, and is not associated with lymph node metastases.[18]

Correct answers to additional questions:

Q2-b, Q3-b, Q4-c, Q5-c.

SUMMARY

HCG are frequently seen in pap smears; however, care must be taken to distinguish benign from malignant causes.

On cervical pap smears, these HCGs may be reported as atypical glandular cells, not otherwise specified (AGC- NOS).

A correlation with clinical history and biopsy findings is necessary to make the final diagnosis.

One of the most important abnormal glandular causes of HCG is endocervical invasive ADC.

Of the various histological subtypes of endocervical ADC, usual endocervical type is the most common and HPV 18 alone accounts for about 50% of all such cases.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The co-author Vinod Shidham, MD, the co-editor-in-chief of this journal does not have any competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is case without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) (or its equivalent).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

ADC – Adenocarcinoma

AGC – Atypical glandular cells

AGC-NOS – AGC: Not otherwise specified.

AIS – Adenocarcinoma in-situ

AS – Arias-Stella

ER – Estrogen receptor

HCG – Hyperchromatic-crowded group

HPV – Human papillomavirus

IHC – Immunohistochemistry

mCEA – Monoclonal carcinoembryonic antigen

MGH – Microglandular hyperplasia

OCP – Oral contraceptive

PR – Progesterone receptor

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

References

- Microglandular Hyperplasia. Available from: http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/cervixMGH.html [Last accessed on 2019 Jul 10]

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation and significance of hyperchromatic crowded groups (HCG) in liquid-based paps. Cytojournal. 2007;4:2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The spectrum of cervical glandular neoplasia and issues in differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:453-83.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aria-Stella reaction in a cervicovaginal smear of a woman undergoing infertility treatment: A case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;32:94-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervical cytology and immunohistochemical features in endometrial adenocarcinoma simulating microglandular hyperplasia. A case report. Acta Cytol. 2000;44:661-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) Available from: http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/cervixAIS.html [Last accessed on 2019 Jul 10]

- [Google Scholar]

- Microglandular hyperplasia has a cytomorphological spectrum overlapping with atypical squamous cells-cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (ASC-H) Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;30:57-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of human papillomavirus DNA in different histological subtypes of cervical adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1055-62.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive analysis of human papillomavirus and chlamydia trachomatis in in situ and invasive cervical adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114:390-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortality trends for cervical squamous and adenocarcinoma in the United States. Relation to incidence and survival. Cancer. 2005;103:1258-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Invasive Cervical Adenocarcinoma. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/invasive-cervical-adenocarcinoma?search=invasive%20endocervical%20adenocarcinoma&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H553367444 [Last accessed on 2019 Jul 11]

- [Google Scholar]

- Epithelial abnormalities: Glandular. In: Nayar R, Wilbur D, eds. The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology: Definitions, Criteria and Explanatory Notes (3rd ed). Switzerland: Springer; 2015. p. :200.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cervical adenocarcinoma: Diagnosis of human papillomavirus-positive and human papillomavirus-negative tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1653-67.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proliferative activity of benign and neoplastic endocervical epithelium and correlation with HPV DNA detection. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2002;21:22-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcinoma of the cervix and tobacco smoking: Collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 13,541 women with carcinoma of the cervix and 23,017 women without carcinoma of the cervix from 23 epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1481-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix in women aged 20-44 years: The UK national case-control study of cervical cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:2078-86.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obesity as a potential risk factor for adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix. Cancer. 2003;98:814-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma: Proposal for a new pattern-based classification system with significant clinical implications: A multi-institutional study. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2013;32:592-601.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]