Translate this page into:

Malignancy rate in nondominant nodules in patients with multinodular goiter: Experience with 1,606 cases evaluated by ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Conventional medical sources recommend the use of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) for single thyroid nodules and the dominant nodule in multinodular goiter (MNG). The purpose of the present study was to analyze the utility of FNAC for multiple thyroid nodules in patients with MNG and to determine the rate of malignancy in teh nondominant nodules.

Materials and Methods:

Our private practice performed ultrasound-guided FNAC on 1,606 patients between February 2001 and February 1, 2010. In the MNG cases, samples were taken from the dominant nodule and from trhee suspicious / nonsuspicious nodules larger than 1 cm on ultrasound. Ninety-four cases were diagnosed as ‘suspiciously malignant’(SUS) or ‘malignant’ (POS) based on FNAC.

Results:

The rate of an SUS / POS diagnosis was 5.7% in the dominant nodules; 2.3% of the nondominant nodules had a SUS / POS diagnosis in FNAC (p = 0.0003). Follow-up revealed malignancy in 15 (35.7%) nondominant nodules and in 27 (64.2%) dominant nodules, with 42 MNG cases undergoing surgery. X test showed a ‘p-level of 0.0003’ between the percentages of SUS / POS diagnosis in dominanat and nondominanat nodules. It was less than the significance level of 0.05. Therefore, the result was regarded to be statistically significant.

Conclusions:

Nondominant nodules could harbor malignancy. The risk of malignancy in nondominant nodules in MNG should not be underestimated. We have shown that the dominant nodule in patients with MNG was in fact about 2.5 times more likely to be malignant than a nondominant nodule. The use of FNAC for nondominant nodules could enhance the likelihood of detecting malignancy in an MNG.

Keywords

Fine needle aspiration cytology

malignancy

multinodular goiter nondominant nodules

thyroid

INTRODUCTION

The essential role of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is to distinguish between benign and malignant nodules. FNAC is also a triage method for determining the medical or surgical therapy for cases in which a clear diagnosis is not possible.[1–3]

Conventional medical sources recommend the use of FNAC for single thyroid nodules and the dominant nodule in multinodular goiter (MNG).[4–6]

Recent publications based on ultrasound and postoperative pathological findings, or the pathological assessment of thyroidectomy specimens, have demonstrated that the malignancy rate is not low in MNG, even in the nondominant nodules.[78]

In the present study, we aim to determine the malignancy rate in the dominant and nondominant nodules in the MNG cases referred to our cytopathology private practice for ultrasound-guided thyroid aspiration cytology (US-FNAC). Furthermore, we also analyzed the role of US-FNAC in determining malignancy in MNG.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In our private cytopathology practice, based on the ‘Scandinavian model’, ultrasound-guided FNAC was performed by a cytopathologist (NP) under the guidance of a radiologist (KY). Physicians primarily refer patients to a cytopathologist for FNAC of the thyroid, breast, and head and neck masses.

Upon assessment of the patient, aspiration was conducted with a 10 cc syringe needle (no. 23) with the assistance of an aspiration pistol attached to the syringe. Cell adequacy was carried out for each patient. The remaining fluid was used to prepare a cell block, and the preparations were stained with Diff-Quik, Papanicolaou, and hematoxylin and eosin.

The present study included 1,606 cases involving US-FNAC, between February 1, 2001, when we started performing US-FNAC, and February 1, 2010.

Ultrasound assessment prior to fine needle aspiration and our ultrasound-guided thyroid aspiration cytology protocol

The physicians who refer thyroid patients to our practice (endocrinologists, ENT surgeons, and internal medicine specialists) request FNAC from adequate nodules based on our ultrasonographic assessment. At our center, we aspirate not only from the dominant nodule, but also from other nodules in the MNG cases. We performed our own protocol in some MNG cases in which FNAC was requested from only a single nodule.

We used ultrasound examination to select the dominant nodule from the nodules with suspicious features, and we obtained FNAC samples from the dominant nodule in the MNG and from at least three other nodules, with a diameter larger than 1 cm (four nodules in total). If the number of suspicious nodules was high, we also obtained specimens from a fifth nodule.

Ultrasound criteria

The following ultrasound data were used by the radiologist for the recognition of a suspicious nodule: (a) hypoechoic appearance, (b) irregular nodular margins, (c) vascular pattern of the nodule from a Doppler ultrasound, and (d) intranodular microcalcific structures.

Cytological assessment

We use the following descriptive terminology for reporting thyroid FNACs, which we find useful in the clinical practice of our medical community: benign (adenomatous nodule, thyroiditis), hypercellular nodule, atypical nodule of undetermined nature, follicular lesion, Hürthle cell lesion, suspicious for malignancy, and malignant (subtypes are provided whenever possible).[3–59] We also add explanatory comments on the meaning of each term, with possible differential diagnosis, except in the benign and malignant groups. The cytological criteria that we used for ‘suspicious’ and ‘malignant’ diagnoses have been outlined in a study by Rossi et al.[9] Only cases with a diagnosis of ‘suspicious for malignancy’ and ‘malignant’ were included in the present study. We refrained from using the Bethesda system because the local clinicians, to whom we gave the thyroid FNAC service, were not yet familiar with the Bethesda reporting system. We maintained a better correlation with them by using descriptive and explanatory cytodiagnostic reports in thyroid FNAC.

Pathological follow-up

As the patients' thyroidectomy procedures were conducted at various training hospitals, we called all the patients on the phone numbers available in our files and requested each patient's pathological results (by fax or hand delivery), to compare them with the cases diagnosed as SUS / POS based on the FNAC samples.

Correlation of the cytologic diagnosis with the pathology reports

The ultrasound images and ultrasonographic nodule mappings of all thyroid cases are kept in our files. The correlation was conducted by comparing of these images with the surgical reports having information on the site, location and diameter of each malignant nodule. The correlation was figured out in all nodules with SUS / POS diagnosis by comparing the ultrasonographic nodule mapping and surgical pathology reports. The suspicious and malignant cytological findings corresponded to the particular nondominant nodule in the depicted, relevant pathology reports.

Statistical analysis

Pearson's chi-square (χ2) test was performed to assess the values of variances between the percentages of suspiciously malignant (SUS) and malignant (POS), dominant and nondominant nodules. A significance level of P < 0.05 was used.

RESULTS

We performed FNAC on 1,606 thyroid cases between February 1, 2001 and February 1, 2010, and 94 cases were diagnosed as SUS / POS′.

Of the 94 cases, 41 were SUS (43.4%) and 53 were POS (56.4%).

Of the 94 cases, 35 were single nodules (37.2%), and 59 were MNG (62.7%).

Eighty-four SUS / POS cases underwent surgery (89.3%). Pathology follow-up was available in all POS cases and all cytologically POS cases (100%) were diagnosed as malignant on a pathological examination.

Pathology follow-up was available in 31 of the 41 cases (75.6%) cytologically diagnosed as SUS and 24 of these cases (77.4%) were malignant. No malignancy was detected in the remaining seven cases (which included four Hashimoto thyroiditis cases, two hyperplastic nodules, and one Hurthle cell adenoma).

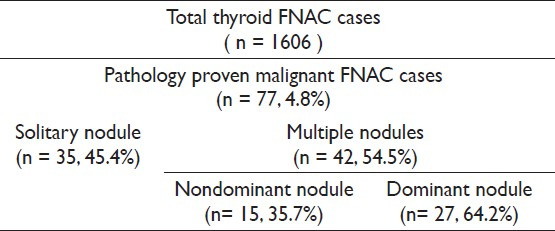

In total, 77 SUS / POS cases were confirmed to be malignant by pathological examination, and the breakdown is presented in Table 1.

Among these 77 cases, 50 were females and 22 were males. The average age was 52, and the age range was 12 to 85 years old.

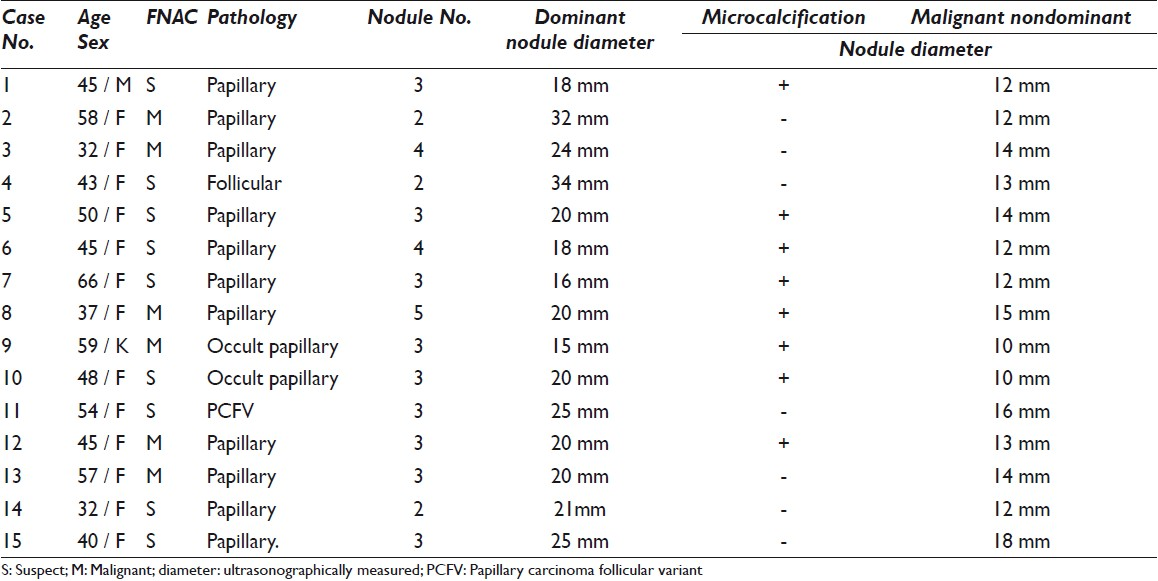

Malignancy was detected in 15 (35.7%) nondominant nodules of the 42 cases with pathologically proven MNG and 27 (64.2 %) dominant nodules, and the breakdown of these cases is presented in Table 2.

The SUS / POS diagnosis rate among 1,606 thyroid patients who underwent FNAC was 5.8% percent. The pathologically confirmed malignancy rate was 4.8%.

Other denominators from our MNG patients were as follows:

One thousand and twenty dominant nodules were aspirated. Fifty-nine (5.7%) of these had SUS / POS diagnosis.

Eight hundred and fourteen nondominant nodules were aspirated.Nineteen (2.3%) cases had SUS / POS diagnosis.

χ2 test showed a ‘P level of 0.0003’ between the percentages of SUS / POS diagnosis in dominant and nondominant nodules. It was less than the significance level of 0.05. Therefore, the result was regarded to be statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Conventional data have recommended the use of thyroid FNAC for both solitary nodules and the dominant nodule in MNG cases.[4–6]

However, some studies have claimed that the likelihood of malignancy in MNG cases is not negligible and that the malignancy ratio of solitary nodules is similar or equivalent to that of MNGs.[71011]

Various studies regarding the malignancy rate in MNGs have been reported in literature. In one group of studies, US-FNAC was used in the preoperative assessments of the thyroid nodules. In the second group of studies, nodules were preoperatively evaluated by ultrasound and there was no indication whether FNAC was used or not. The second group of studies was mainly based on the pathological results of thyroidectomy specimens. Studies in both groups were conducted in many geographical regions (e.g., USA, Spain, France, Italy, Croatia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and India). In the studies that utilized US-FNAC for the preoperative assessment of thyroid nodules, the occurrence of malignancy in MNG was 5,[10] 6.3,[12] 9,[13] 15,[14] and 36%.[15] In the second group of studies, the occurrence of malignancy in MNG was 4.1,[16] 12.2,[17] 13,[18] 13.7,[19] and 18.9%.[20] Interestingly, Sipos stated that the average ratio of malignancy occurring in an MNG was approximately 14%.[21]

According to the above-mentioned studies, we observe that on an average, the rate of malignancy in a multinodular goiter was between 13 and 15%, ranging from 4.1 to 36%. On the other hand, these studies generally provided the overall malignancy rate in an MNG. The distinction between dominant and nondominant nodules was not specified.

There are limited studies, however, that refer to the risk of malignancy in the dominant and nondominant nodules.[1420] A study by Frates et al. revealed that the prevalence of thyroid cancer was similar between patients with a solitary nodule (175 of 1181 patients, 14.8%) and patients with multiple nodules (120 of 804, 14.9%). This study also showed that malignancy occurred in patients with multiple nodules larger than 10 mm, cancer was multifocal in 46 and 72% of cancers in the largest nodule.[14]

Only a limited number of studies refer to the role of FNAC in detecting malignancy in MNG. This issue was recognized in a publication by Kojic et al. (2004); however, no reference was made to the distribution of dominant versus nondominant nodules in the malignant MNG cases.[15]

The present study may be regarded as a preliminary study in this context because we used the FNAC approach in both dominant and nondominant nodules for MNG. In 42 MNG cases, malignancy was detected by FNAC in 15 nondominant nodules (35.7%) and 27 dominant nodules (64.2%). Importantly, these diagnoses were verified by pathological examinations. Although we are aware that the total number of cases included in our study is limited the results demonstrate that the likelihood of detecting malignancy in nondominant nodules in MNG should not be underestimated. We have shown that the dominant nodule in patients with MNG is in fact about 2.5 times more likely to be malignant than that in a nondominant nodule, in keeping with the study by Frates et al.[14] Meanwhile, we did not capture all the malignancies in the dominant and nondominant nodules in our series as we did not include other cases, such as, atypical nodule, follicular/Hürtle cell lesion and so on, rather than SUS / POS.

In addition to ultrasound reports, all patients who referred to our cytopathology practice for FNAC underwent an ultrasonographic assessment, which was performed by our radiologist. The radiologist examined all nodules by considering their solid hypoechoic appearance, irregular or blurred margins, intranodular vascular pattern, and microcalcifications.[1222–24] Even if the cases did not fulfill these characteristics, we performed FNAC on the dominant nodule and three other nodules that were larger than 1 cm.

In 15 cases of nondominant malignant nodules, the diameter of the positive nondominant nodules was between 10 mm and 18 mm in our cases. Interestingly, the diameter of malignancy-negative dominant nodules in the same group varied between 15 mm and 32 mm. Therefore, nondominant nodules should also be taken into account for FNAC diagnosis in MNG cases, regardless of the diameter of the nodule, if the ultrasonographic criteria are suspicious.

The present retrospective study was based on the FNAC findings. Although the ultrasonographic criteria mentioned in the materials and methods section of the article were followed at the time FNAC, only the diameter and microcalcification of the nodules was included in our database. No other worrisome ultrasound characteristics were noted in our reports. Microcalcification was observed in eight (53.3%) of the fifteen nondominant malignant cases. We had two cases of nondominant nodules with a diameter of 1 cm and FNAC was performed in both cases because we observed microcalcification; these nodules were reported as cytologically suspicious, and occult papillary carcinoma was diagnosed in both cases based on the pathological findings.

Although the likelihood of malignancy varies in MNG, as mentioned above, the generally accepted average value is approximately 14%.[21] The results of these studies contradict the conventional data, which only recommend FNAC in the dominant nodule in MNG. Therefore, the 2009 Revised American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines recommends the application of FNAC in up to four nodules that are larger than 1 cm, even if the nodules are not suspicious.[25] Despite the results being based on a relatively small patient population, our study demonstrated the importance of the recommendation of FNAC sampling of dominant and nondominant nodules in MNG.

The most important aspect of detecting malignancies with FNAC in MNG is to always perform FNAC with ultrasound guidance. We believe that performing FNAC on only the palpable dominant nodule is not sufficient. Using FNAC within the framework of a multidisciplinary protocol, preferably in cooperation with the same team, working in harmony with each other (i.e., radiologist, endocrinologist / surgeon and cytopathologist), increases the malignancy detection rate in MNG.[2426]

CONCLUSIONS

Regardless of who performs the FNAC [i.e., the cytopathologist, radiologist, nuclear medicine specialist, or the clinical physician (endocrinologist / surgeon)], we should not adhere to the conventional view that specimens only need to be acquired from the dominant nodule in MNG.

The other nodules should also be evaluated, and attention should be paid to nondominant nodules that also appear to be suspicious on an ultrasound.

We suggest that the risk of malignancy in nondominant nodules in an MNG should not be underestimated. In addition, clinicians should appreciate the importance of using a multidisciplinary approach for US-FNAC detection of malignancy.[27]

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE. All authors are responsible for the conception of this study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) (or its equivalent) of all the institutions associated with this study. Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

EDITORIAL / PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model(authors are blinded for reviewers and reviewers are blinded for authors)through automatic online system.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2011/8/1/19/86970.

REFERENCES

- Fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodules: a study of 4703 patients with histologic and clinical correlations. Cancer. 2007;111:306-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration of follicular lesions of the thyroid. Diagnosis and follow-up. CytoJournal. 2006;3:9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid and parathyroid. In: Geisenger KR, Silverman JF, eds. Fine needle aspiration cytology of superficial organs and body sites (1st ed). Churchill Livingstone: Philadelphia; 1999. p. :85-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid. In: Cibas ES, Ducatman BS, eds. Cytology: diagnostic principles and clinical correlates (2nd ed). Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003. p. :247-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid. In: Bibbo M, Wilbur DC, eds. Comprehensive cytopathology (3rd ed). Philadelphia: Saunders-Elsevier; 2008. p. :633-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid carcinoma in single cold nodules of multinodular goiters. Endocr Pract. 2000;6:5-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prospective analysis of 518 cases with thyroidectomy in Turkey. Endocr Regul. 2005;39:85-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic efficacy of conventional as compared to liquid-based cytology in thyroid lesions:evaluation of 10.360 fine needle aspiration cytology cases. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:659-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- The use of fine-needle aspiration biopsy under ultrasound guidance to assess the risk of malignancy in patients with a multinodular goiter. Thyroid. 2000;10:235-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Discordance between cytologic results in multiple nodules within the same patient. Acta Cytol. 2010;54:673-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of malignancy in nonpalpable thyroid nodules: predictive value of ultrasound and color-Doppler features. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1941-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Utility of fine-needle aspiration for diagnosis of carcinoma associated with multinodular goitre. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004;61:732-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and distribution of carcinoma in patients with solitary and multiple nodules on sonography. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3411-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Importance of FNAC in the detection of tumor within multinodular goitre of the thyroid. Cytopathology. 2004;15:206-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Do long-standing nodular goitres result in malignancies? Aust N Z J Surg. 1994;64:180-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multinodular goiter: surgical management and histopathological findings. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;259:217-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- The incidence of thyroid carcinoma in solitary cold nodules and in multinodular goiters. Surgery. 1986;100:1128-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- The incidence of thyroid carcinoma in multinodular goiter: retrospective analysis. Acta Biomed. 2004;75:114-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of thyroid gland volume in preoperative detection of suspected malignant thyroid nodules in a multinodular goiter. Arch Surg. 2008;143:558-63. discussion 563

- [Google Scholar]

- Advances in ultrasound for diagnosis and management of thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19:1363-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current status of fine needle aspiration for thyroid nodules. Adv Surg. 2006;40:223-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of carcinoma in ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration cytology of thyroid nodules. Endocr J. 2008;55:135-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- The National Cancer ınstitute Thyroid fine needle asiration state of the science conference: A summation. CytoJournal. 2008;5:6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19:1167-214.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid malignancy in multinodular goitre and solitary nodule. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1995;40:310-12.

- [Google Scholar]