Translate this page into:

Micropapillary urothelial carcinoma: Cytologic features in a retrospective series of urine specimens

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

The micropapillary variant of urothelial carcinoma (uPC) is a rare variant of urothelial carcinoma that carries a poor prognosis. Definitive surgery may represent optimal management of low stage tumors. Urine cytology is indispensable in the screening and follow-up of urinary tract cancer. However, cytopathological criteria for diagnosis of uPC and its differentiation from conventional urothelial carcinoma (CUC) are not well-defined.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty-five cases of histologically confirmed micropapillary uPC from 21 patients were compared to 25 cases of histologically confirmed high-grade CUC.

Results:

In uPC cases, cell clusters were identified in 13 of 25 specimens from 10 patients. Six of the 13 specimens containing cell clusters corresponded to surgical pathology specimens in which micropapillary carcinoma accounted for at least 50% of total carcinoma. In contrast, only 1 of the 12 urine specimens devoid of cell clusters corresponded to surgical specimens in which micropapillary carcinoma accounted for at least 50% of total carcinoma. Cytomorphologic features of urinary specimens from patients with histologically confirmed micropapillary carcinoma were generally similar to those from patients with high-grade CUC, making it difficult to distinguish these entities in exfoliative urine specimens.

Conclusions and Summary:

Further investigation of the core cytopathological characteristics of uPC is warranted to refine its diagnostic criteria by exfoliative urine cytology.

Keywords

Cytology

carcinoma

exfoliative

micropapillary

urothelial

BACKGROUND

The micropapillary variant of urothelial carcinoma (uPC) is a rare but distinctive variant of urothelial carcinoma initially described as having histopathologic features that resemble papillary serous ovarian carcinoma.[1] uPC has an aggressive clinical course and poor prognosis[2–8] with 5- and 10-year overall survival rates of 51 and 24%, respectively, regardless of stage at presentation.[9] In that same series, 53% of cases were upstaged after definitive surgical treatment, including 27% with occult lymph node metastases. Furthermore, bladder-sparing treatments, including neoadjuvant chemotherapy and intravesical bacille Calmette-Guerin, decreased survival compared with early definitive surgical treatment. Because definitive surgical treatment may represent optimal management of low stage tumors,[910] early detection is crucial.

Urine cytology is indispensable in the screening and follow-up of urinary tract cancer. Urothelial carcinomas, especially high-grade urothelial carcinoma and carcinoma in situ (CIS), are routinely diagnosed by urine cytology, because their diagnostic criteria are well established. However, cytopathological diagnostic criteria for uPC remain poorly defined, as various reports have described different morphologic characteristics.[11–15] In the current study, the cytopathological characteristics of uPC are further defined, and their utility in diagnosis of uPC by exfoliative urinary cytology are examined in a large case series.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

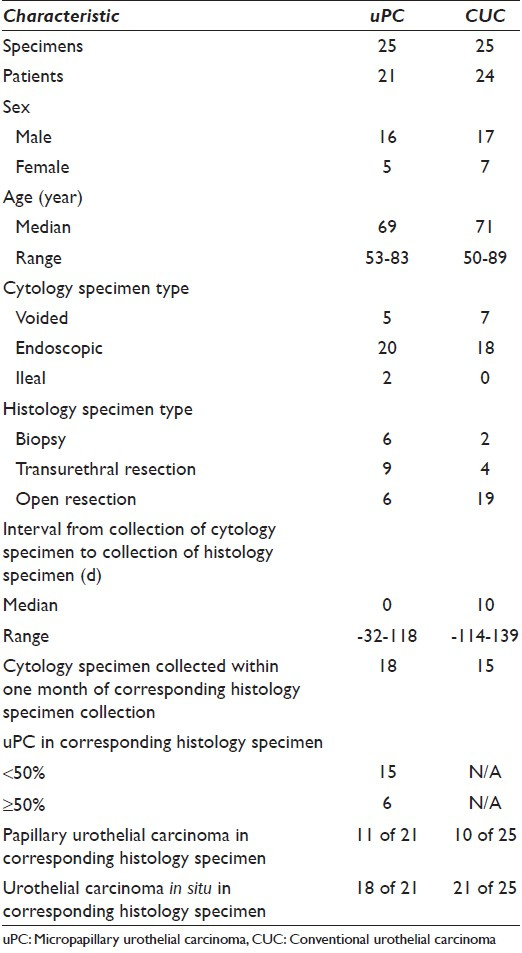

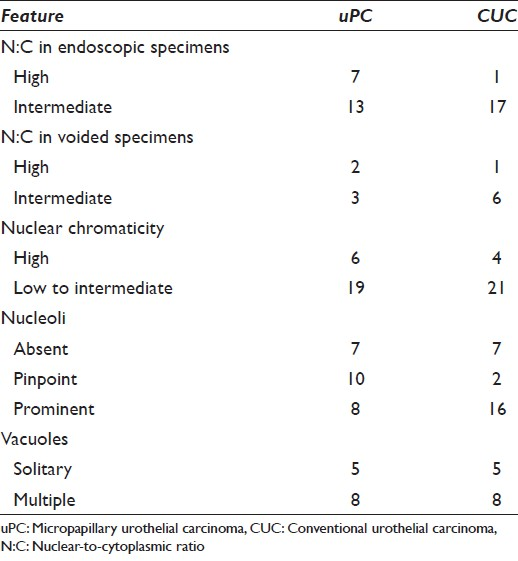

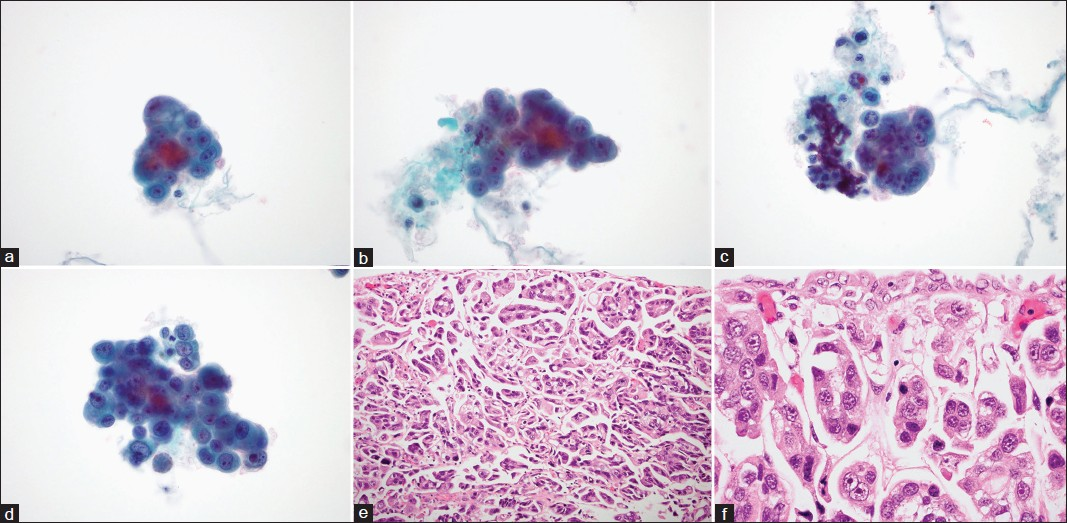

Cases of histologically confirmed urothelial carcinoma with a micropapillary component as well as concurrent or near-concurrent cytologic urine specimens positive or suspicious for malignant cells were retrospectively identified by computerized search. Histologically confirmed cases of high-grade conventional urothelial carcinoma (CUC) with or without a papillary component for which patients had undergone definitive surgical resection and concurrent or near-concurrent urine collection with cells positive or suspicious for malignancy were identified for comparison. Cases with a component of sarcomatoid differentiation, small cell carcinoma, or mucinous adenocarcinoma were excluded from analysis. Cases of both upper and lower tract urothelial carcinoma were included in the analysis. All cytologic specimens were obtained by noninvasive collection of voided urine or at the time of endoscopy (cystoscopy with or without ureteroscopy), and cytologic specimens were prepared using ThinPrep™ (Cytyc Corporation, Boxborough, MA). Characteristics of the specimens and the patients from which they came are listed in Table 1.

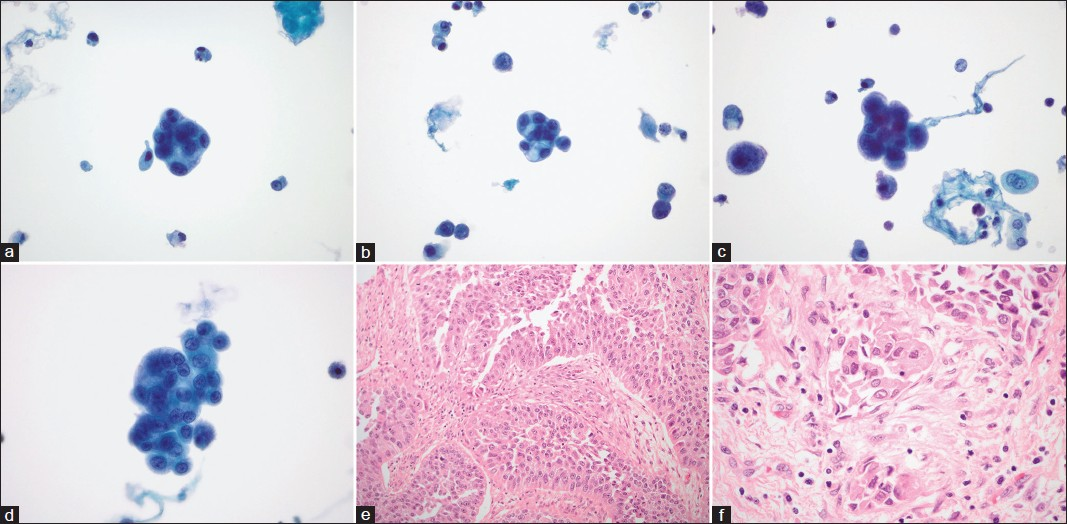

All cytologic specimens were reviewed by two study pathologists in order to confirm malignancy as well as to evaluate the presence and extent of architectural and cytomorphologic criteria. Where differences in opinion arose, a third pathologist was consulted. Architectural features observed in urine specimens are listed in Table 2. They include cellularity, presence of single malignant cells, and presence of malignant cell clusters. Clusters of malignant cells were further subdivided by morphology into “papillary” (containing a true fibrovascular core), “micropapillary” (tightly packed cells in a three-dimensional arrangement with regular borders with minimal scalloping and without fibrovascular core), and “flat” (all others). Cytomorphologic features observed in urine specimens are listed in Table 3. They include nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio (N:C), nuclear chromaticity, quantity of nucleoli, size of nucleoli (if present), cytoplasmic volume, and presence of cytoplasmic vacuoles. Cytoplasmic vacuoles were further subdivided into “single” or “multiple.” All scores were determined by consensus. Other cytologic features, including presence of squamous metaplasia, mitotic figures, background inflammation and necrosis, and irregularity of nuclear and cell membranes, were noted where appropriate but not scored.

All histologic specimens were reviewed by two study pathologists in order to evaluate the presence and extent of morphologic criteria. These include presence of papillary carcinoma, CIS, singly vacuolated cells, multiply vacuolated cells, and nucleoli as well as percentage of invasive carcinoma with micropapillary histology and percentage of total carcinoma with micropapillary histology. Other histologic features, including background inflammation, squamous metaplasia, anaplasia, and mitotic activity were noted where appropriate.

Using SPSS, version 19.0, comparisons of individual features were performed with the Chi-square test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for ordinal variables. The Bonferroni adjustment was used to correct for multiple comparisons. As no comparisons reached statistical significance (P < 0.05, before adjustment) after univariate analysis, no multivariate analysis was performed to evaluate clusters of features.

RESULTS

Micropapillary carcinoma

Twenty-five cytology specimens from 21 patients with uPC and 21 corresponding surgical pathology specimens from 20 of those patients were identified, spanning a 4 year period. The median age of the patients was 69 (range, 53-83). The urine specimens [Figure 1a–d] included 5 voided specimens and 20 endoscopic collections, 2 of which came from ileal conduits. The surgical specimens [Figure 1e and f] included 6 endoscopic biopsies, 9 transurethral resections, and 6 open resections. Surgical specimens were collected from 32 days before to 118 days after collection of the corresponding urine specimen, although the median time (interval) between collections was 0 (concomitant). Patient and specimen characteristics, architectural features, and cytomorphologic findings are detailed in Table 1–3, respectively.

- Exfoliative cytomorphology of micropapillary variant of urothelial carcinoma (uPC) (a-d) and corresponding histomorphology (e and f). (a-d) Tightly packed clusters in a three-dimensional arrangement with regular borders with minimal scalloping contain atypical, focally vacuolated, hyperchromatic, nucleolated cells with mostly high and focally intermediate N:C. A few single malignant cells (c and d) are also present (papanicolaou stain on ThinPrep™, ×600). (e and f) Tightly packed clusters of invasive uPC arranged in lacunar spaces. Cells contain markedly atypical nuclei and show focally vacuolated cytoplasm (H and E, ×200 and × 600, respectively)

Review of surgical pathology specimens revealed variable admixture of uPC and CUC within the same specimen. The micropapillary component, both invasive and non-invasive, represented less than 10% of total carcinoma in 10, 10-50% in 5, 50-90% in 3, and >90% in an additional 3 of 21 specimens. In only 1 case was the micropapillary component exclusively non-invasive.

Cytomorphologic review revealed specimens with variable appearance. Abundant single malignant cells were identified in 21 of 25 urine specimens, including 17 of 18 specimens corresponding to surgical pathology specimens containing flat CIS. Cell clusters were identified in 13 of 25 specimens from 10 patients. Six of the 13 specimens containing cell clusters corresponded to surgical pathology specimens in which uPC accounted for at least 50% of total carcinoma. In contrast, only 1 of 12 urine specimens devoid of cell clusters corresponded to surgical specimens in which uPC accounted for at least 50% of total carcinoma. Only 3 of 21 urine specimens containing abundant single malignant cells corresponded to surgical pathology specimens in which uPC accounted for at least 50% of total carcinoma. In contrast, all 4 urine specimens containing moderate or rare single malignant cells corresponded to surgical pathology specimens in which uPC accounted for at least 50% of total carcinoma. Identified clusters had micropapillary morphology in both voided urine specimens containing cell clusters. The clusters had micropapillary morphology in 10 of the 11 endoscopic urine collections containing cell clusters, and such clusters were abundant in 3 specimens. One of 25 urine specimens contained flat clusters, and none contained papillary clusters. Additional cytomorphologic features include markedly increased N:C in 9 of 25 specimens, marked nuclear hyperchromasia in 6 of 25 specimens, and prominent nucleoli in 8 of 18 specimens in which nucleoli were present. Cytoplasmic vacuoles, including solitary and multiple (or both in 1 case), were identified in malignant cells in 12 of 25 specimens.

Conventional urothelial carcinoma

Twenty-five cytology specimens from 24 CUC patients and 25 corresponding surgical pathology specimens from those 24 patients were identified over a 2 year period. The patient population included 17 men and 7 women. The median age of the patients was 71 (range, 50-89). The urine specimens [Figure 2a–d] included 7 voided specimens and 18 endoscopic collections, none of which came from ileal conduits. The surgical specimens [Figure 2e and f] included 2 endoscopic biopsies, 4 transurethral resections, and 19 open resections. Surgical specimens were collected anywhere from 114 days before to 139 days after collection of the corresponding cytology specimen, although the median time between collections was 10 days. Patient and specimen characteristics, architectural features, and cytomorphologic findings are detailed in Tables 1–3, respectively.

- Exfoliative cytomorphology of conventional urothelial carcinoma (CUC) (a-d) and corresponding histomorphology (e and f). (a-d) Tightly packed cell clusters in a three-dimensional arrangement. Borders of the cell clusters vary from regular to scalloped. The cells demonstrate hyperchromatic chromatin, nucleoli, focally vacuolated cytoplasm, and intermediate to high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. A few preserved single malignant cells are best seen in B and C (papanicolaou stain on ThinPrep™, ×600). (e and f) CUC demonstrating (e) papillary architecture with true fibrovascular cores and (f) invasion (H and E, ×200 and × 600, respectively)

Review of surgical pathology specimens revealed a mixture of cases containing invasive and in situ papillary and non-papillary urothelial carcinoma. Specifically, a papillary component was identified in 10, and an in situ component was identified in 21 of 25 specimens.

Cytomorphologic review revealed specimens with variable appearance. Abundant single malignant cells were identified in 20 of 25 urine specimens, including 17 of 20 specimens corresponding to surgical specimens containing flat CIS. Cell clusters were identified in 16 of 25 specimens from independent patients. Identified clusters had micropapillary morphology in 1 of 5 voided urine specimens containing cell clusters and in 9 of the 11 endoscopic urine collections containing cell clusters. Eight of 25 urine specimens contained flat clusters, and none contained papillary clusters. Additional cytomorphologic features include markedly increased N:C in 2 of 25 specimens, marked nuclear hyperchromasia in 4 of 25 specimens, and prominent nucleoli in 16 of 18 specimens in which nucleoli were present. Cytoplasmic vacuoles, including solitary and multiple (or both in 1 case), were identified in malignant cells in 12 of 25 specimens.

DISCUSSION

The urine cytology findings of uPC are only available in a limited number of cases, in which a wide range of cytological characteristics are variably described: Low to high cellularity; clean background to background with severe, acute inflammation; rare to frequent single malignant cells; small, tightly cohesive clusters, branching or non-branching papillary structures without fibrovascular cores, clusters arranged in a honeycomb, floral, or cauliflower pattern, three-dimensional cells balls with scalloped borders or smooth outlines, or rosette-like or inside-out microacinar structures with peripherally located nuclei; well-defined membranous borders; scant to moderate, thick cytoplasm; single, large intracytoplasmic vacuoles or several, smaller vacuoles; low to high N:C; monomorphic to pleomorphic nuclei; rounded to irregularly outlined or indented nuclei with irregularly thickened nuclear membrane; overlapping, hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular to coarsely granular chromatin; prominent, centrally located nucleoli; atypical mitoses.[11–14] The aim of the current study is to further define the cytopathological characteristics of uPC by comparing a large, retrospective series of urine specimens from patients with histologically confirmed uPC to urine specimens from patients with extensively sampled, histologically confirmed CUC. A wide range of morphologic criteria were considered, and cytomorphologic features were also correlated with method of urine specimen collection, presence of papillary urothelial carcinoma and CIS, and extent of uPC in corresponding surgical pathology specimens. Although numerous morphologic features were readily apparent in urine specimens from patients with uPC, including the presence of tightly packed (micropapillary) cell clusters in a three-dimensional arrangement with regular borders and minimal scalloping in 12 of 25 specimens from 9 patients, these features were also identified in 10 of 25 urine specimens from independent patients with high grade CUC and were, therefore, not specific for uPC.

There are several important reasons for recognizing the micropapillary variant of urothelial carcinoma in exfoliative urinary specimens. These reasons include appropriate treatment, including early definitive surgical treatment[910] and correct classification of distant metastases. In addition, the amount of micropapillary component may correlate – inversely – with patient prognosis. In one retrospectively collected series of histologic cases, Alvarado-Cabrero et al., reported a trend toward an association between the proportion of uPC and survival. Patients with more than 50% uPC had a higher relative mortality risk than patients with urothelial carcinoma, not otherwise specified; patients with less than 50% uPC did not.[8] In another retrospectively collected series of cases, Compérat et al., also reported a trend toward association between the proportion of uPC and survival. Patients with less than 10% uPC had a mean survival of 18 months. Patients with between 10 and 50% uPC had a mean survival of 16.8 months. Patients with at least 50% uPC had a mean survival of 12.1 months. Patients with any proportion of uPC were at high risk of being upstaged at cystectomy and of dying of cancer.[5] In the current study, cell clusters were identified in 6 of 7 (86%) specimens from 6 patients for whom uPC comprised at least 50% of total carcinoma in the corresponding surgical pathology specimen. In contrast, cell clusters were identified in only 6 of 16 (38%) specimens from 14 patients for whom uPC comprised less than 50% of total carcinoma in the corresponding surgical pathology specimen. Because the presence of cell clusters is not specific for uPC, it is unlikely that the presence of cell clusters will be of utility in differentiating uPC from CUC in exfoliative urine specimens. However, the presence of cell clusters in exfoliative urine specimens known to harbor uPC may suggest a high proportion of uPC and therefore, a poor prognosis. This result requires confirmation in a prospective, observational study including a greater number of patients.

The data submitted here directly controvert those presented by Zhu et al., who concluded after examining a series of 23 uPC and 28 CUC cases that the findings of cytoplasmic vacuoles and micropapillary structures in urine cytology specimens are associated with uPC but not CUC on subsequent biopsy.[15] However, there are significant differences in the methods employed between the two studies that may account for the different results. First and foremost, all specimens in the current study were prepared using ThinPrep™, while an unknown proportion of the specimens in the prior study were prepared as cytospins rather than using ThinPrep™. While no effect of ThinPrep™ on the urothelial cluster formation and presence of urothelial cytoplasmic vacuoles has been reported, it is possible that ThinPrep™ may at least partially disrupt epithelial cluster formation as it does in fine needle aspiration biopsy specimens of breast fibroadenoma.[1617] Second, while cytologic features in the prior study were evaluated by a single pathologist, cytomorphologic, and architectural features in the current study were evaluated by two pathologists in order to augment descriptive reproducibility with review by a third pathologist in cases where differences in opinion arose. Differences in reproducibility may explain why 21 of 51 (41%) cases in the prior study were identified as containing true papillary structures while no cases in the current study contained true papillae despite a study population in which 21 of 46 (46%) corresponding histology specimens contained papillary urothelial carcinoma. Third, the authors of the prior study did not report the proportion of micropapillary architecture in each of its uPC cases. It is possible that the prior study consisted predominantly of cases containing high proportions of uPC, which, in the current study were far more likely to contain cell clusters. Finally, it should be noted that urine specimen collection differed significantly between the two studies. In the current study, 38 of 50 (76%) specimens were collected by endoscopic methods; in the prior study, 26 of 51 (51%) specimens were collected by endoscopic methods.

Method of specimen collection is one of several factors that may potentially alter the cytologic appearance of exfoliative urine specimens independent of the presence and extent of uPC, including specimen cellularity, prior treatment, and presence and extent of other subtypes of urothelial carcinoma.[18–20] For example, cell clusters are a common finding in urine specimens but are more common in instrumented specimens, and cell clusters may be identified in both benign and malignant conditions. Since a majority of specimens in this study were collected by endoscopic methods (20 of 25 for uPC, 18 of 25 for CUC), it should be emphasized that cytomorphologic features described in the current study may not be observed in voided specimens. Furthermore, one might reasonably expect a greater prevalence of cell clusters in specimens with higher cellularity. While cell clusters were present almost exclusively in CUC patient specimens of moderate or high cellularity (15 of 15 specimens from separate patients compared to 1 of 10 specimens of low cellularity from 9 patients), such an association was not observed in uPC patients, as clusters were present in 9 of 15 specimens of moderate or high cellularity from 14 patients compared to 4 of 10 specimens of low cellularity from 7 patients. Alterations in urine specimen cellularity and cytomorphology have also been reported after intravesical pharmaceutical instillation (although changes in the presence of urothelial cell clusters after such instillation have not been reported). Therefore, in order to limit the cytomorphologic effects of possible intravesical pharmaceutical instillation[2122] and changes in tumor composition over time, urine cytology specimens with concurrent or near-concurrent histologic specimens were selected for analysis. Finally, specimen cellularity should correlate with the presence of flat urothelial CIS, which is known to have a propensity to exfoliate, specifically as single cells.[23] Because so few urine specimens in this study corresponded to surgical pathology specimens devoid of flat CIS – 3 of 22 in the series of uPC patients and 3 of 25 in the series of CUC patients – it is difficult to draw conclusions about the role of concomitant urothelial CIS in the diagnosis of uPC in exfoliative urinary specimens. Because cases with a component of sarcomatoid differentiation, small cell carcinoma, or mucinous adenocarcinoma were excluded from analysis, the extent to which they may interfere with accurate diagnosis of uPC is unknown. Taken together, the role of independent factors such as method of specimen collection, specimen cellularity, heterogeneity of tumor over time, and presence and extent of other subtypes of urothelial carcinoma in the diagnosis of uPC in exfoliative urinary specimens remains incompletely defined and warrants further investigation.

The clinical utility of establishing criteria for cytopathologic identification of uPC depends, to an extent, on interobserver reproducibility of those criteria. However, in their study of the histopathologic diagnosis of uPC, Sangoi et al., found that interobserver reproducibility was only moderate (κ = 0.54).[24] It is possible that one or more of the cases classified in the current study as uPC would be interpreted as CUC or, inversely, one or more of the cases classified in the current study as CUC would be interpreted as uPC at another institution. Because all CUC patients underwent definitive surgical resection, and all resection specimens were extensively sampled, it is unlikely that clinically significant foci of uPC were missed in cases included in the CUC series.

Multiple molecular and cytogenetic changes have been described in bladder tumors, and several of these have been utilized to develop urine-based tests both for initial disease detection and surveillance for recurrence. Of the cell-based tests, two have obtained Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. ImmunoCyt/uCyt™ (DiagnoCure Inc., Québec, QC, Canada) is a fluorescent test that uses monoclonal antibodies directed against antigens expressed by low grade urothelial carcinomas. It has not been validated in a large-scale prospective multicenter validation study. UroVysion™ (Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL, USA) is a multi-target multicolor fluorescent in situ hybridization assay that uses probes directed against pericentric regions of chromosomes known to be aneuploid in urothelial carcinoma, as well as to the 9p21 locus of the p16 tumor suppressor gene, which may also be overexpressed in urothelial carcinoma.[25] Two FDA trials have been conducted with UroVysion, both exclusively on voided urine specimens.[2627] The molecular characteristics of uPC are incompletely defined, although recent studies have suggested that uPC may harbor molecular alterations distinct from CUC. These include alterations in mucine-1 (MUC1),[28] Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6),[29] and serine/threonine kinase 15 (Aurora-A/STK-15),[30] none of which are directly detected by ImmunoCyt/uCyt. The cytogenetic characteristics of uPC have not been described. The efficacy of molecular and cytogenetic testing for detection of uPC in urine and its differentiation from CUC requires further investigation.

CONCLUSION(S) AND SUMMARY

Detailed urine cytologic findings are presented and compared between two large series: One of cases of uPC; one of cases of CUC. Although the cytopathologic findings of uPC include features associated with classical histopathologic descriptions of uPC such as tightly packed, three-dimensional cell clusters with regular borders with minimal scalloping, as well as cytoplasmic vacuolization these findings were generally similar to high-grade CUC, making it difficult to distinguish uPC from CUC in exfoliative urine specimens.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author.

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

AS conceived of the study. AS, JJH, and JPC participated in its design. All authors participated in data acquisition. JJH and JPC analyzed and interpreted the data. AS, JJH and JPC drafted the article. All authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) (or its equivalent) of all the institutions associated with this study as applicable.

Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

EDITORIAL / PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2013/10/1/4/107986

REFERENCES

- Micropapillary variant of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Histologic pattern resembling ovarian papillary serous carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:1224-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Invasive micropapillary urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1159-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Micropapillary bladder carcinoma: A clinicopathological study of 20 cases. J Urol. 1999;161:1798-802.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histological variants of urothelial carcinoma: Diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic implications. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:S96-S118.

- [Google Scholar]

- Micropapillary urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder: A clinicopathological analysis of 72 cases. Pathology. 2010;42:650-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Micropapillary variant of urothelial carcinoma in the upper urinary tract: A clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:62-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Micropapillary bladder cancer: A review of Léon Bérard Cancer Center experience. BMC Urol. 2009;9:5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Micropapillary carcinoma of the urothelial tract. A clinicopathologic study of 38 cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2005;9:1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Micropapillary bladder cancer: A review of the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience with 100 consecutive patients. Cancer. 2007;110:62-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The case for early cystectomy in the treatment of nonmuscle invasive micropapillary bladder carcinoma. J Urol. 2006;175:881-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Micropapillary variant of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: A report of three cases with cytologic diagnosis in urine specimens. Acta Cytol. 2001;45:599-604.

- [Google Scholar]

- Micropapillary carcinoma of the urinary bladder: A case report. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:344-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Micropapillary carcinoma of the urinary bladder: Report of a case and review of its cytologic features. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:784-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urine cytology of micropapillary carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:852-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urine cytomorphology of micropapillary urothelial carcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;24:Epub ahead of print.

- [Google Scholar]

- Breast fine-needle aspiration. A comparison of thin-layer and conventional preparation. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:349-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interpretation of fine-needle aspirates processed by the ThinPrep technique: Cytologic artifacts and diagnostic pitfalls. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;23:6-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of atypical urine cytology in a tertiary care center. Cancer. 2005;105:468-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytology of grade 1 papillary transitional cell carcinoma. A comparison of cytologic, architectural and morphometric criteria in cystoscopically obtained urine. Acta Cytol. 1996;40:676-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Low grade transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Cytologic diagnosis by key features as identified by logistic regression analysis. Cancer. 1994;74:1621-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Difficulties in evaluating urinary specimens after local mitomycin therapy of bladder cancer. Diagn Cytopathol. 1989;5:117-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin effects in voided urine cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:425-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interobserver reproducibility in the diagnosis of invasive micropapillary carcinoma of the urinary tract among urologic pathologists. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1367-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- The development of a multitarget, multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization assay for the detection of urothelial carcinoma in urine. J Mol Diagn. 2000;2:116-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical evaluation of a multi-target fluorescent in situ hybridization assay for detection of bladder cancer. J Urol. 2002;168:1950-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reflex UroVysion testing of bladder cancer surveillance patients with equivocal or negative urine cytology: A prospective study with focus on the natural history of anticipatory positive findings. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;127:295-301.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathogenesis of invasive micropapillary carcinoma: Role of MUC1 glycoprotein. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:1045-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- KL-6 is another useful marker in assessing a micropapillary pattern in carcinomas of the breast and urinary bladder, but not the colon. Med Mol Morphol. 2009;42:123-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aurora-A/STK-15 is differentially expressed in the micropapillary variant of bladder cancer. Urol Int. 2009;82:312-7.

- [Google Scholar]