Translate this page into:

More focus on atypical glandular cells in cervical screening: Risk of significant abnormalities and low histological follow-up rate

*Corresponding author: Chenghong Yin, Department of Pathology, Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, Capital Medical University, No. 17, Qi He Lou Street, Dongcheng, Beijing, China. modscn@126.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Zhong P, Yin C, Jin Y, Chen T, Zhan Y, Tian C, et al. More focus on atypical glandular cells in cervical screening: Risk of significant abnormalities and low histological follow-up rate. CytoJournal 2020;17:22.

Abstract

Objectives:

Atypical glandular cells (AGC) detected by Papanicolaou (Pap) smears are in close relation with adenocarcinoma and precursors detected by histopathology. Yet, sometimes the cytological diagnosis of AGC has been neglected. With increase of adenocarcinoma and precursors, we need more focus on glandular abnormalities.

Material and Methods:

Clinicopathological data of patients who had AGC on Pap smears between April 2015 and October 2018 and underwent histological follow-up were retrieved from the computerized database of Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, Capital Medical University. Patients with a prior history of cancer were excluded from the study. Statistical analyses were performed using Pearson’s Chi-square test in SPSS software version 23. P < 0.05 (two sided) was considered as statistical significance.

Results:

Liquid-based cytological examination of the uterine cervix was carried out in 164,080 women. Five hundred and twenty-five women were diagnosed with AGC, 314 with not otherwise specified (AGC-NOS), and 211 with favor neoplastic (AGC-FN). Only 310 cases had histological follow-up, 168 women (168/314, 53.5%) originally with AGC-NOS on Pap smears, and 142 (142/211, 67.3%) with AGC-FN. The median age of histological significant abnormalities was 46.7 years, and 126 women (126/162, 77.8%) were postmenopausal. Sixty-six cases (66/168, 39.3%) of AGC-NOS had significant abnormalities (96/142, 67.6%, AGC-FN). One hundred and sixty-two cases of significant abnormalities included 40 high-grade squamous abnormalities and 122 glandular abnormalities. AGC-FN was more likely to be associated with a clinically significant abnormalities (P < 0.001) compared to AGC-NOS.

Conclusions:

Patients with AGC on Pap smears are in close relation with significant abnormalities, especially with significant glandular abnormalities on histopathology slices. AGC should be evaluated vigilantly with histological workup, especially if patients are diagnosed with AGC-FN and are aged 41–60 years. We need more focus on AGC.

Keywords

Atypical glandular cells

Cytology

Adenocarcinoma

INTRODUCTION

With the wide application of cervical cancer screening, the incidence of squamous cancer and its precursors has been considerably reduced worldwide, whereas there is a rise in adenocarcinoma.[1-3] It leads us to focus on recognition of the risk factors of adenocarcinoma. Atypical glandular cells (AGC) on Papanicolaou (Pap) smears are defined as glandular cells exhibit changes beyond those encountered in benign reactive processes, but lack the features of adenocarcinoma in situ or invasive adenocarcinoma on Pap smears.[4]

Do AGC prove to be significant abnormalities? The result becomes significant for clinical management. It is reported that 18–83% of patients with AGC have significant abnormalities on follow-up histopathology.[5-8] Notwithstanding, sometimes not enough attention is paid to women of AGC.

The objective of our study is to investigate the clinical significance of AGC. Our hospital is a large-scale specialized hospital in China. Only few patients, with gynecological diseases at their first visit or consultation to our hospital, have been lost to other hospitals in our follow-up. Therefore, the data are representative to some extent.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Classification of AGC

AGC is subdivided into not otherwise specified (AGC-NOS) and favor neoplastic (AGC-FN).[4,9-11] A retrospective study was done between April 2015 and October 2018. During this period, a total of 164,080 women underwent cervical screening with ThinPrep liquid-based cytology test in Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, Capital Medical University. Five hundred and twenty-five women were diagnosed with AGC and then 310 of these cases were subjected to colposcopy-directed biopsies, cervical biopsies, cone biopsies, fractional curettage, or hysterectomies with histological findings. The cytological slides were stained using the Pap method, and the histological sections were stained using the hematoxylin-eosin method. Relevant study flowchart is presented in Figure 1. Women were excluded from the study if they had a previous history of cancer.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23 for Windows. Frequency tables were analyzed using the Chi-square test. Bivariate correlations between ordered variables were analyzed using Spearman correlation analysis. P < 0.05 (two sided) was considered as statistical significance.

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee. Informed consent was not obtained as there is no direct patient involvement.

RESULTS

Cytology

A total of 164,080 Pap smears were evaluated during the study period. Glandular cell abnormalities were encountered in 597 cases (0.4%) and AGC in 525 cases (0.3%). The number of cases with AGC-NOS was 314 and 211 with AGC-FN. The age of 525 women with AGC ranged from 22 to 78 years (median age: 46.7 years) at presentation. Incidence and prevalence of AGC was most common at the age of 41–50 followed by 51–60 and 31–40. About 84.4% of the 314 women with AGCNOS were aged between 31 and 60 years (AGC-FN, 78.2% of 211 women), whereas only 15.6% were aged below 31 years and above 60 (AGC-FN, 21.8%). About 46.0% (236 cases) of the women with AGC were postmenopausal. In Table 1, the age distribution is represented.

- Study flowchart.

| AGC | Age | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21–30 (n=42) (%) |

31–40 (n=118) (%) |

41–50 (n=168) (%) |

51–60 (n=154) (%) |

61–70 (n=40) (%) |

71–80 (n=13) (%) |

||

| NOS | 33 (10.5) | 71 (22.6) | 102 (32.5) | 92 (29.3) | 13 (4.1) | 3 (1) | 314 |

| FN | 9 (4.3) | 37 (17.5) | 66 (31.3) | 62 (29.4) | 27 (12.8) | 10 (4.7) | 211 |

Pearson’s Chi-square test for women aged 31–60 years with AGC-NOS versus women aged 21–30 years or above 60 years with AGC-NOS: P=0.000. AGC: Atypical glandular cells, not otherwise specified (AGC-NOS), favor neoplastic (AGC-FN)

Cytohistological relation

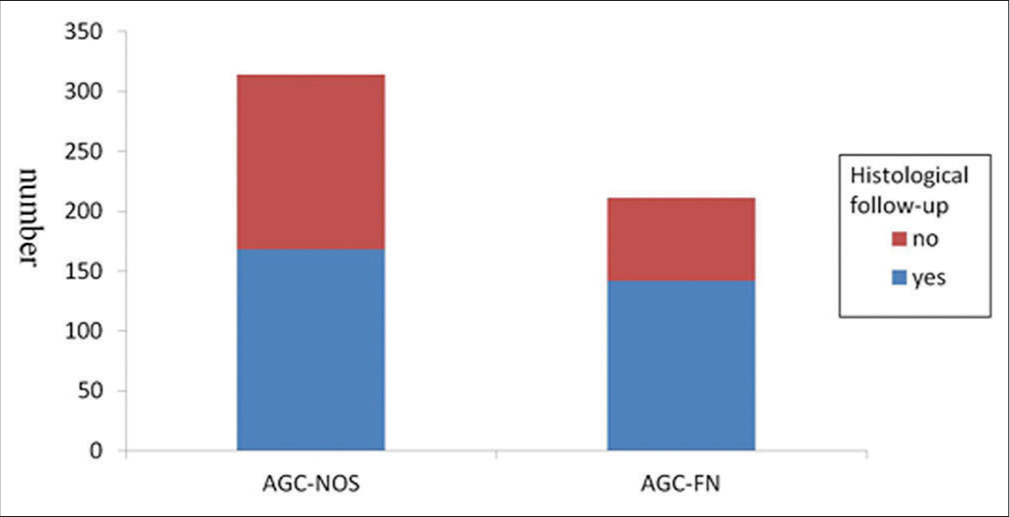

Table 2 shows the histological follow-up after AGC. Only 310 women (310/525, 59.1%) with AGC had histological follow-up, 168 women (168/314, 53.5%) originally with AGC-NOS, and 142 (142/211, 67.3%) with AGC-FN [Figure 2]. Among 168 cases of histological follow-up, 102 cases were diagnosed of benign, 20 cases of significant squamous abnormalities, and 46 cases of significant glandular abnormalities after AGC-NOS. Among 142 cases, the data of the upper histological follow-up were 46, 20, and 76, respectively, after AGC-FN. Incidence and prevalence of significant abnormalities were highest when AGC was found at ages 51–60 followed by 41–50 [Table 3]. About 77.8% (126/162) of the women with significant abnormalities were postmenopausal. Benign histology mainly comprised inflammation, polyp, metaplasia, low-grade squamous intraepithelial (LSIL), and hyperplasia without atypia and so on. Significant abnormalities comprised significant squamous abnormalities and significant glandular abnormalities. Significant squamous abnormalities included high-grade squamous intraepithelial (HSIL) and squamous cell carcinoma. Significant glandular abnormalities included adenocarcinoma (originated from cervix, endometrial, or extra uterus), cervical high-grade cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasia, and atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

| Cytology | Histological follow-up | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign (n=148) (%) | Significant squamous abnormalities (n=40) (%) | Significant glandular abnormalities (n=122) (%) | ||

| AGC-NOS | 102 (60.7) | 20 (11.9) | 46 (27.4) | 168 |

| AGC-FN | 46 (32.4) | 20 (14.1) | 76 (53.5) | 142 |

Pearson’s Chi-square test for histological follow-up of AGC-NOS versus that of AGC-FN: P=0.000. AGC: Atypical glandular cells, not otherwise specified (AGC-NOS), favor neoplastic (AGC-FN)

| Histology | Age (n=162) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21–30 | 31–40 | 41–50 | 51–60 | 61–70 | 71–80 | |

| Significant abnormalities | 8 | 26 | 50 | 59 | 16 | 3 |

Patients aged 41–60 years with AGC are at higher risk for significant abnormalities. AGC: Atypical glandular cells

- Histological follow-up of AGC-NOS and AGC-FN. AGC: Atypical glandular cells, not otherwise specified (AGC-NOS), favor neoplastic (AGC-FN).

AGC-FN (96/142, 67.61%) was more likely to be associated with a clinically significant abnormalities (P < 0.001) compared to AGC-NOS (66/168, 39.29%). The diagnosis of AGC on Pap smears was associated with significant glandular abnormalities compared with significant squamous abnormalities on histopathology.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of AGC is reported to range from 0.1 to 2.1% in the literature.[12-15] It was 0.32% in our study. From the data in this study, the peak occurrence age of both cytological AGC and significant pathological abnormality was from 41 to 60. The rate of significant pathological abnormalities was higher if the women with AGC were aged ranged 41–60, especially in postmenopausal state. Age was a risk factor.

AGC on Pap smears can be associated with benign, premalignant, and malignant conditions on followed-up histopathology. Some studies reported squamous epithelial abnormalities on histopathology were most common.[4,5,15,16] In our study, non-significant abnormalities were separated from significant abnormalities on histopathology to avoid further active clinical procedures. AGC proved to be significant glandular abnormalities in this study (occupying up to 39.4%), compared with significant squamous abnormalities (12.9%). The diagnosis of AGC in our study was vigilant, which needed a consensus by three experienced cytologists. It indicated patients with AGC carried a significant risk for having a diagnosis of significant abnormalities, especially significant glandular abnormalities on histopathology.

AGC-FN was more closely associated with significant abnormalities than AGC-NOS, found to have statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). There is a considerable variation of AGC in association with significant abnormalities. To subdivide AGC into AGC-NOS and AGC-FN is necessary. In the literature, the detection rates of malignant or premalignant abnormalities ranged from 15% to 43% for AGC-NOS, and the corresponding range was 41–100% for AGC-FN.[7,17-20] LSIL and hyperplasia without atypia were excluded from significant abnormalities in our study, with which patients usually received conservative treatment, resulted in decrease of positive rate on histopathology in our study. It was worth mentioning that three cases of AGC-FN on cytology: (1) Case of the cervical biopsies was diagnosed of LSIL and (2) were negative fractional curettage for the 1st time. By reviewing the Pap smears, all the three patients underwent fractional curettage for the 2nd time 4 months later. The histological results were endometrial carcinoma or HSIL, respectively. Clinicians and patients should attach more attention to AGC-FN on cytology. If cytologists highly suspect severe abnormality and histopathology diagnosis is negative otherwise, clinicians had better communicate with cytologists and take further examination. Sixty-six cases of AGN-NOS (66/168, 39.3%) were diagnosed of significant abnormalities on histopathology. AGC-NOS should not be ignored as benign lesions either.

In our study, 525 cases were diagnosed of AGC, yet only 310 cases had subsequent histopathology (AGC: 310/525, 59.1%; AGC-NOS: 168/314, 53.5%; and AGN-FN: 67.3%). A nationwide audit found that one-third of women with AGC lacked histological follow-up.[21] This lack of follow-up might be associated with very high risks for cancer. The major hurdles are as follows: Clinicians have not enough knowledge of AGC. Cytological diagnosis of AGC is not accurate. Poor compliance of some patients also leads to low follow-up of AGC. It needs increased awareness of the necessity for histological follow-up after AGC. We would recommend that all smears reported as ACG should be followed-up with biopsy and curettage for confirmation of the diagnosis.

Forty cases of significant squamous abnormalities (including HSIL and squamous cell cancer) on histopathology were originally diagnosed of AGC on Pap smears. In our study, 148 cases of benign lesions followed up, severe chronic endocervicitis, polyps and submucosal leiomyomas, and microglandular hyperplasia were most common, 67, 46, and 18, respectively. These benign lesions led to reactive glandular hyperplasia/hypertrophy, which mimicked glandular abnormalities on cytology. These findings led us to focus on the cytologic characteristics of AGC in an effort to identify features that may be associated with underdiagnosis or overdiagnosis of this lesion, but some cases continue to be problematic when evaluated based on cytologic features.

CONCLUSION

Patients aged 41–60 years with AGC are at higher risk for significant abnormalities, especially for glandular abnormalities. To subdivide AGC into AGC-NOS and AGC-FN is necessary, since AGC-FN is more closely associated with significant abnormalities than AGC-NOS. Clinicians should carry out aggressive procedure in patients with AGC, especially with AGC-FN, to enhance the histological follow-up rate. When the corresponding histopathology after AGC-FN is negative, clinicians should thoroughly evaluate it. If necessary, a further clinical procedure should be carried out. The increase incidence of adenocarcinoma and precursors calls for a focused effort to be awareness of AGC.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Dr. Jing Pan (an experienced cytopathologist in Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, Capital Medical University) for providing guidance for cytopathological diagnosis.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

Study design: Pingping Zhong, Chenghong Yin and Yulan Jin; reviewing slides and collecting data: Tianbao Chen, Pingping Zhong, Yang Zhan, Cheng Tian, Li Zhu; writing draft: Pingping Zhong, Xingzheng Zheng.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, ethical approval was not sought. All authors confirm that there are no ethical concerns.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

AGC – Atypical glandular cells

AGC-NOS – Atypical glandular cells, not otherwise specified

AGC-FN – Atypical glandular cells, favor neoplastic

LSIL – Low-grade squamous intraepithelial

HSIL – High-grade squamous intraepithelial

HG-CGIN – Cervical High-grade cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasia.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

References

- Eleven-year review of data on pap smears in Saudi Arabia: We need more focus on glandular abnormalities! Ann Saudi Med. 2017;37:265-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervical cancer trends in the United States: A 35-year population-based analysis. J Womens Health. 2012;21:1031-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potential effects of updated Pap test screening guidelines and adenocarcinoma in situ of the cervix. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:759-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epithelial abnormalities: Glandular. In: Nayar R, Wilbur DC, eds. The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology Definitions, Criteria, and Explanatory Notes (3rd ed). Berlin: Springer International Publishing AG Company; 2015. p. :193-240.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of atypical glandular cells in Pap smears: Is it a hit and miss scenario? Acta Cytol. 2013;57:45-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distribution of cell types differs in Pap tests of squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2017;6:10-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk of high-grade lesions after atypical glandular cells in cervical screening: A population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017070.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relationship of atypical glandular cell cytology, age, and human papillomavirus detection to cervical and endometrial cancer risks. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:243-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinicopathological significance of atypical glandular cells on Pap smear. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56:76-83.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The role of the Pap smear diagnosis: Atypical glandular cells (AGC) In: Srivastava S, ed. Intraepithelial Neoplasia. UK: IntechOpen; 2012. p. :365-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic and histologic correlation of atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:214-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Histological follow-up in patients with atypical glandular cells on Pap smears. J Cytol. 2017;34:203-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detecting uterine glandular lesions: Role of cervical cytology. Cytojournal. 2016;13:3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance, Histologic findings and proposed management. J Reprod Med. 2002;47:266-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atypical glandular cells and cervical cancer: systematic review. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2011;57:229-33.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of women with atypical glandular cells on cervical cytology. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;36:23-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical significance of atypical glandular cells on Pap smears: Experience from a region with a high incidence of cervical cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:496-500.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of outcome in women with borderline glandular change on cervical cytology. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;147:83-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical significance of atypical glandular cells by the 2001 Bethesda system in cytohistologic correlation. Acta Cytol. 2008;52:563-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical significance of atypical glandular cells in the Bethesda system 2001: A comparison with the histopathological diagnosis of surgically resected specimens. Cancer Invest. 2014;32:105-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk of invasive cervical cancer after atypical glandular cells in cervical screening: Nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2016;352:276.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]