Translate this page into:

The gray zone squamous lesions: ASC-US / ASC-H

*Corresponding author: Dr. Meherbano M. Kamal, Department of Pathology, Government Medical College, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India. dr.mmkamal@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Kattoor J, Kamal MM. The gray zone squamous lesions: ASC-US / ASC-H. CytoJournal 2022;19:30.

Abstract

The unequivocal and easily recognizable entities of LSIL and HSIL pose no diagnostic problems for a trained eye. However, when the defining morphologic features are either qualitatively or quantitatively insufficient, it is then that the borderline category of “Atypical Squamous cells” (ASC) may have to be used. Scant and suboptimal preparations (mainly in conventional smears) are the common causes that hinder confident decision-making. The binary classification of the ASC category has been retained in The Bethesda System 2014. It includes ASC of undetermined significance (ASC-US) when the atypia is seen in mature cells and ASC-cannot rule out high-grade lesion (ASC-H) when borderline changes are seen in less mature, smaller metaplastic cells or smaller basaloid cells. There are many criticisms of the ASC category. The major one is its subjective and inconsistent applications and the low interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility. However, studies have shown that if we eliminate ASC-US, the LSIL rate will increase. If ASC-H is eliminated, the chances of detecting true lesions are reduced. Hence, there are strong reasons to retain the ASC category. The usual problems leading to the categorization of such cells as atypical are hyperchromasia beyond that acceptable as reactive change; abnormal chromatin pattern that is not overt dyskaryosis; minor variations in nuclear shape; and membrane outlines. Qualifying the atypical cells precisely in one of the categories has bearing on the clinical management and follow-up of the patient. Surveillance of women under the ASC-US category is either by repeat smear at 6 months and 1 year or by reflex human papillomaviruses DNA testing. Women with a Pap smear interpretation of ASC-H are directed to undergo immediate colposcopy. This article describes in detail the morphologic features of the ASC category, doubts about the correct interpretation of the chromatin pattern of the cells in question, and the differential diagnosis between normal, reactive, or inflammatory conditions, and LSIL/HSIL.

Keywords

Atypical squamous cells

Atypical squamous cells-US

Atypical squamous cells-H

Differential diagnosis of atypical squamous cells-US

Differential diagnosis of atypical squamous cells-H

Challenges in cytomorphologic interpretations of atypical squamous cells

INTRODUCTION AND TERMINOLOGY

The term atypical squamous cells (ASCs) were introduced in The Bethesda System (TBS) to designate equivocal cytologic changes that may reflect a squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL). Papanicolaou in 1941 introduced the numerical terminology which consisted of Classes I–V.[1] The present terminology ASC comes under Papanicolaou Class II which is a mixture of reactive changes to koilocytosis and atypia. Later, it was found that Class II was inadequate to accommodate the diversity of benign lesions. Then, the concept of precursor lesions emerged. Reagan in 1961 introduced the term “dysplasia” for the intraepithelial changes in tissue biopsies collected from the cervix.[2] This created a wide variety of terminologies such as keratinized dysplasia, non-keratinized dysplasia, and metaplastic dysplasia (each with mild, moderate, and severe sub-classes). This classification was more subjective and thus the clinicians found its application difficult from the patient management point of view. Richard in 1966 introduced cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) classification with CIN I, CIN II, and CIN III based on the tissue architecture.[3] However, the term neoplasia for lowgrade CIN was objected to by experts.

Then, Meisels in 1976 recognized manifestations of genital human papillomavirus (HPV) infection which is reflected in the smear as koilocytosis and is considered as less than true dysplasia. Subsequently, HPV DNA was identified in a majority of cervical neoplasm and HPV was considered as a key link in the pathogenesis of cervical cancer. Koilocytotic changes were seen associated with dysplasia/CIN. Hence, the separation of the morphology of HPV as a separate entity from dysplasia/CIN became biologically invalid.

In 1988, a meeting was convened with experts from all over the world at Bethesda, Maryland, USA, to discuss the standardization of terminologies. A common terminology that helps in the management was emerged, called “The Bethesda System” (TBS).[4] TBS was modified in 1991, 2001, and recently in 2014.[5-9]

The term ASCUS was introduced into the TBS 1991 to reflect the reality and limitations of light microscopy in classifying borderline lesions. ASCs were categorized into ASCs of undetermined significance (ASC-US) which was further qualified as “favor reactive,” favor “SIL,” and “NOS.” This led to the overuse of this category and consequently caused dilemmas for the clinicians due to the lack of standardized follow-up protocols and variability of outcomes.

With the advances in the understanding of the biology of HPV infection and the natural history of cervical cancer, as well as the results of the NCI-ALTS trial (ASC-US/ LSIL Triage Study), the focus of cervical cancer screening shifted from treating any CIN to focusing on treating the high-grade CIN. Based on this concept, in the TBS 2001, the term ASC-US was replaced by ASC. The latter was further qualified as ASC-US and ASC-H (ASC-cannot exclude HSIL).[6] This dichotomous reporting terminology for atypia is in keeping with the 2-tiered reporting scheme for HPV-related squamous lesions which is based on our current understanding of the natural history of HPV-related infections – low-grade changes represent largely transient HPV infection and high-grade morphology represents a precancerous lesion.

In the 2014 Bethesda System, ASC continues to be included under squamous epithelial cell abnormality, with subcategorization as “atypical squamous cells-undetermined significance” (ASC-US) and “atypical squamous cells-cannot exclude a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion” (ASC-H). As a general guide, the majority of ASC interpretations should fall into the ASCUS qualifier (90–95%) with only 5–10% in the ASC-H category.[10,11]

ASC

The ASC designation may arise either due to numerous morphologic features or technical problems related to smear preparation like active smearing of material. Numerous non-neoplastic conditions may produce cytologic changes that raise consideration for an ASC designation, including inflammation, air-drying (inherent to the conventional Pap smear), atrophy with degeneration, hormonal effects, and other artifacts. These issues result in the artifacts that make it difficult for the cytotechnologist and pathologist to adequately visualize the nuclear details of the cells in question, resulting in a less than a definitive diagnosis.

Technical problems related to immediate wet fixation are eliminated in the liquid-based preparations (LBPs), such as SurePath and Thin Prep. This allows the pathologist and cytotechnologist to better differentiate between cellular changes due to reactive conditions, definitive squamous atypia, and dysplastic lesions. This is not to say that ASC interpretations are eliminated by the adoption of the LBPs, but the laboratory staff has the opportunity to refine their morphologic criteria, eliminating certain “ASC” cases arising from poor preparation, and better-identifying cases that may harbor abnormality. In many instances, the process that resulted in the ASC interpretation remains undefined, even following a diagnostic workup.

Definition

ASC refers to cytologic changes suggestive of SIL, which are qualitatively or quantitatively insufficient for a definitive interpretation. The interpretation of ASC requires that the cells in question should be showing squamous differentiation, increased nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, and minimal increase in nuclear chromasia, chromatin clumping, membrane irregularity, smudging, or multinucleation.[12] ASC category was developed to designate the interpretation of an entire specimen, not individual cells, because atypia in individual cells remains a highly subjective and, hence, variable interpretation.[13,14] The category of ASC is the most prevalent of all abnormal cervical cytology interpretations.

Binary classification of ASC category includes:

ASC-US refers to changes that are suggestive of LSIL but which are insufficient for a definitive interpretation as such

The ASC-H category was developed to highlight the minor subset of ASC considered suspicious for a cancer precursor lesion, that is, HSIL.

In contrast to ASC-US, which is a common cytologic interpretation that has been extensively characterized in large studies, ASC-H interpretations are relatively uncommon.[15]

Occasionally, a specimen with cytologic features that lie between LSIL and HSIL is encountered. In such cases, the 2014 Bethesda System recommends an interpretation of ASC-H in addition to LSIL interpretation.[2,3,7] This indicates that definite LSIL is present as well as some cells suggest the possibility of HSIL. Based on HPV biology and behavior of pre-invasive HPV-associated squamous lesions, the focus is aimed at the detection and treatment of HSIL.[16,17]

In screening programs representative of the US population, approximately 40–50% of women with ASC are infected with high-risk types of HPV.[18-20] Therefore, updated guidelines published in October 2007 give a greater emphasis on high-risk HPV (hrHPV) testing.[15,21-23] HPV testing is useful as a secondary test, following an ASC-US cytology test, for triage to colposcopy. The ASC-US/LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) which began in 1997 also considers hrHPV as the most cost-effective triage test.[24,25] New algorithms are proposed on special populations such as adolescents and pregnant women.

ASC-US

It must be emphasized that this category is not a waste paper basket. Before using this category, previous cytology reports, reports of HPV test and colposcopy, and present cytologic findings should be carefully reviewed and judiciously evaluated and then those features that are most consistent with benign reactive changes may be classified as “negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy” (NILM) whenever possible. The three prerequisites in the interpretation of ASC are as follows:

The cells should be squamous – The epithelial cells that are generally incorporated in the ASC-US category are the mature squamous and squamous metaplastic cells exhibiting changes that are minimal and fall short of a diagnosis of LSIL or HSIL

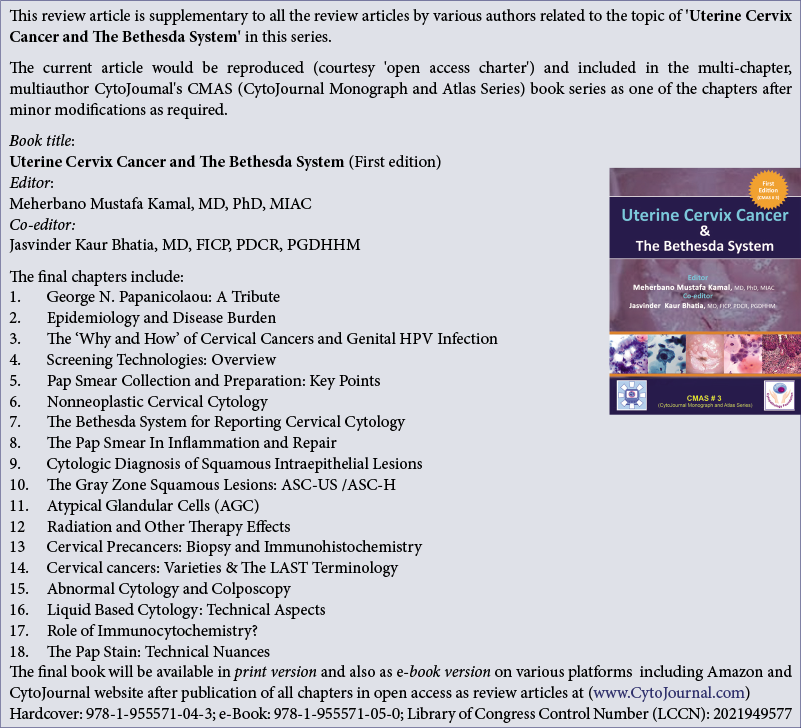

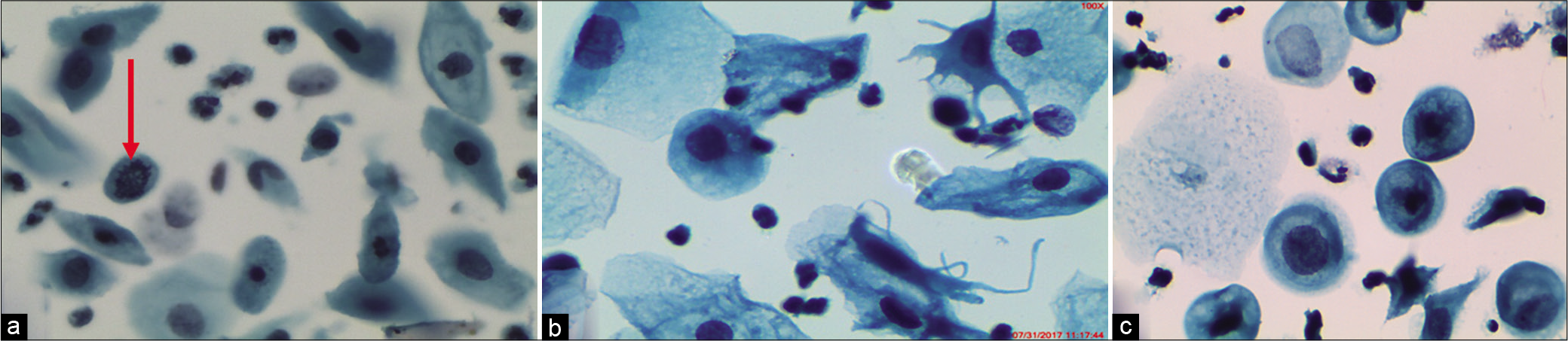

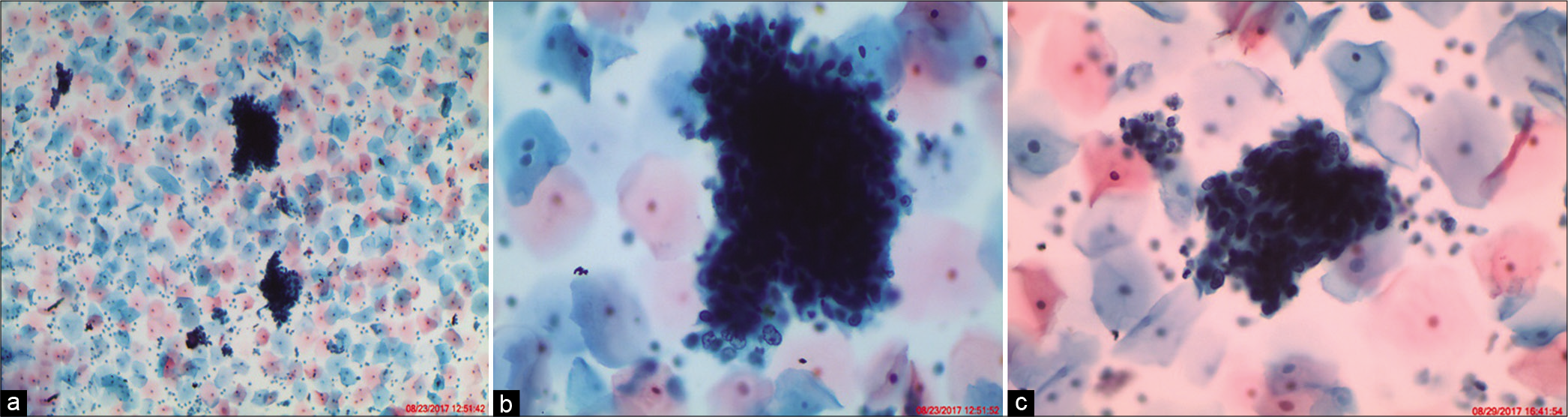

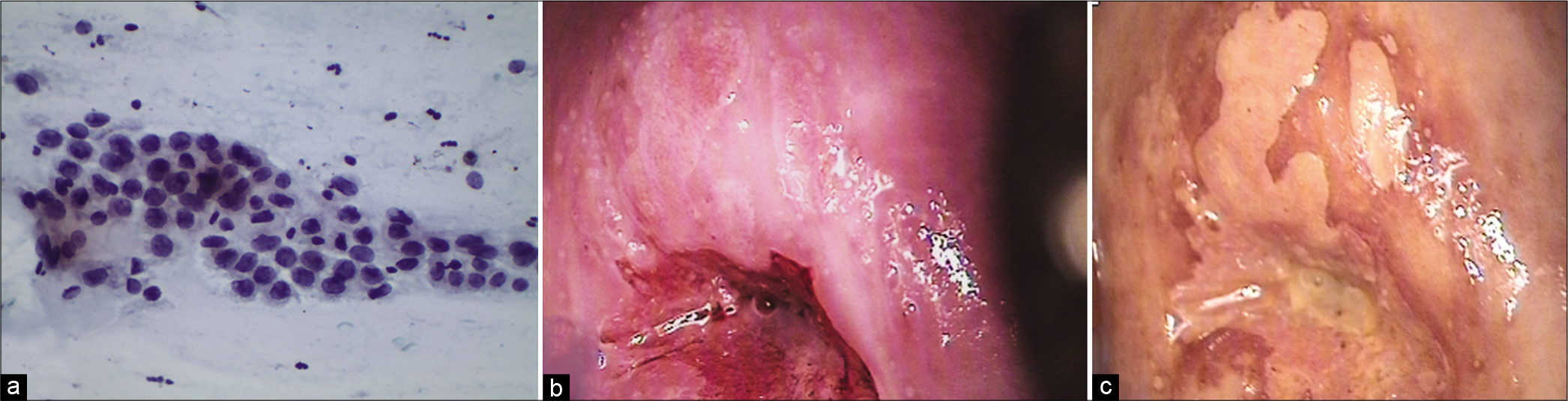

The nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio should be increased – The nuclei are slightly enlarged and this enlargement is compared to the unequivocally normal nucleus of the same cell type [Figure 1a-c]

-

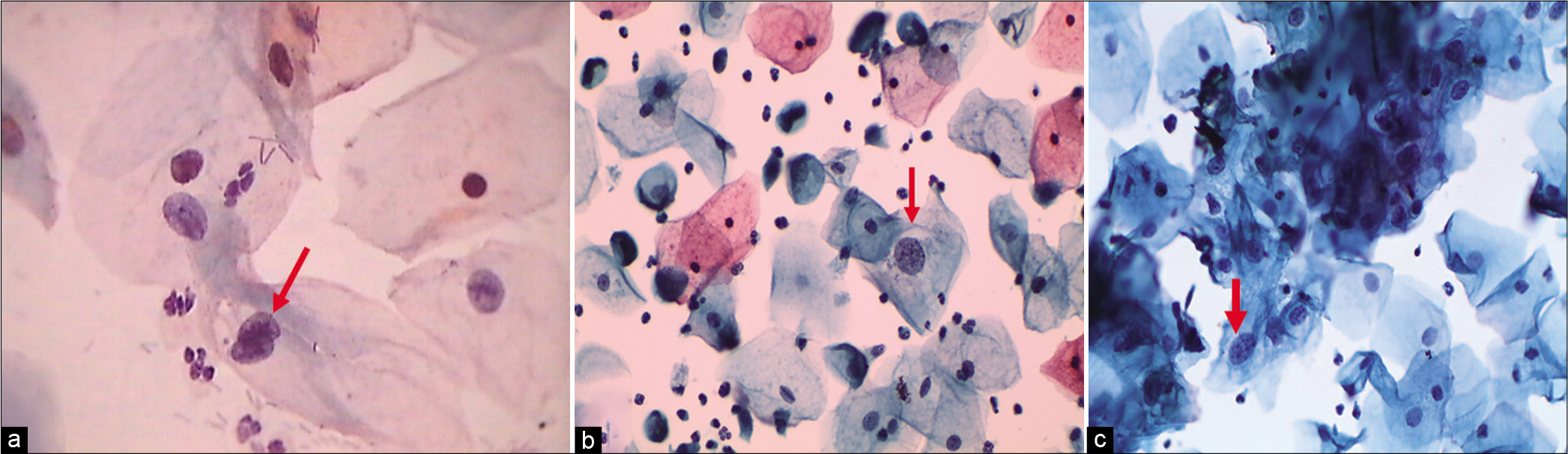

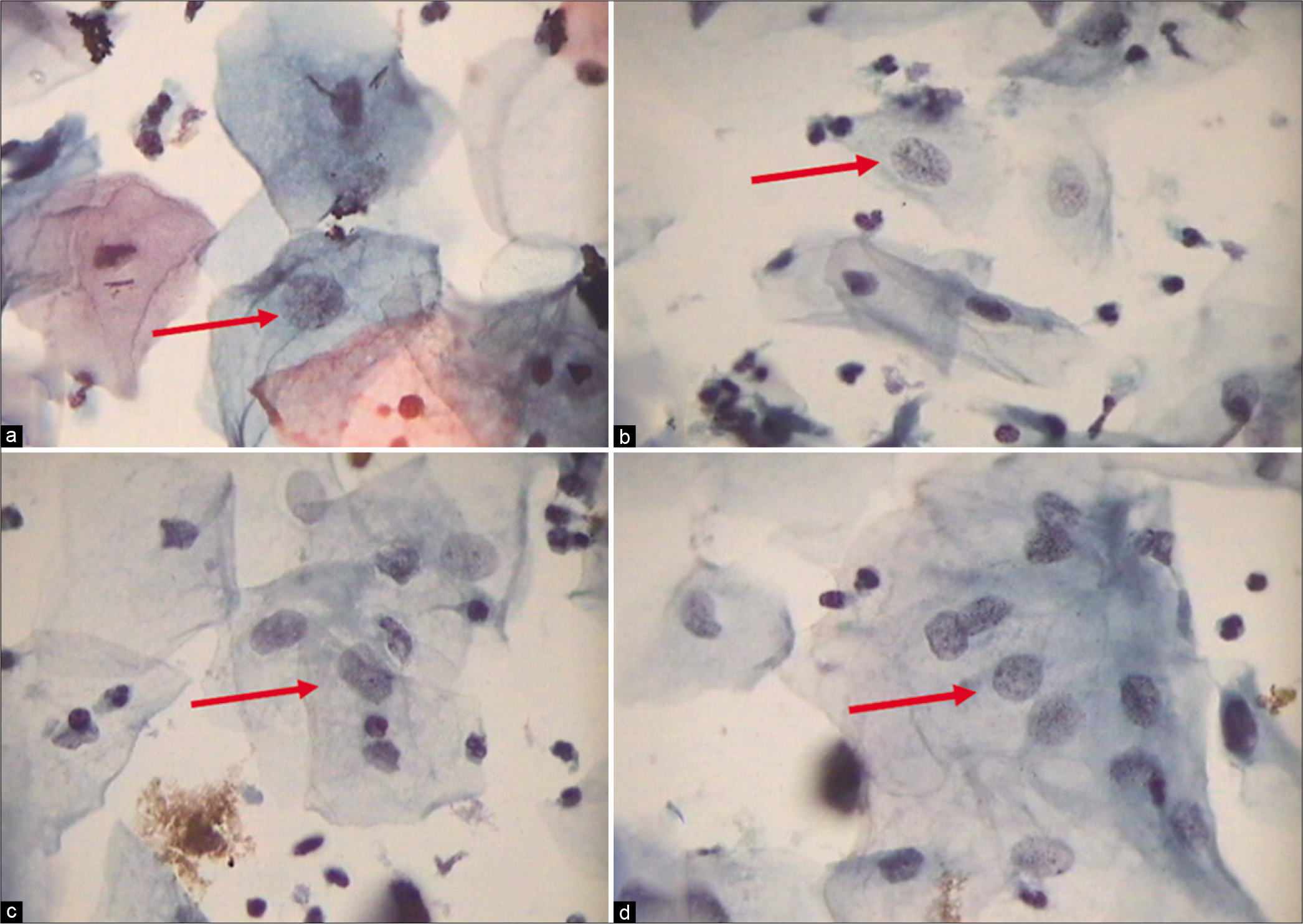

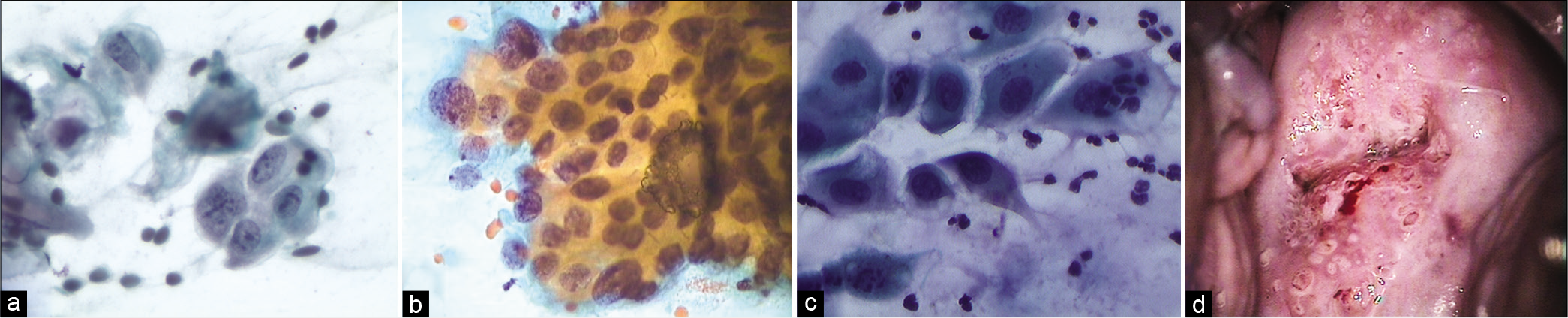

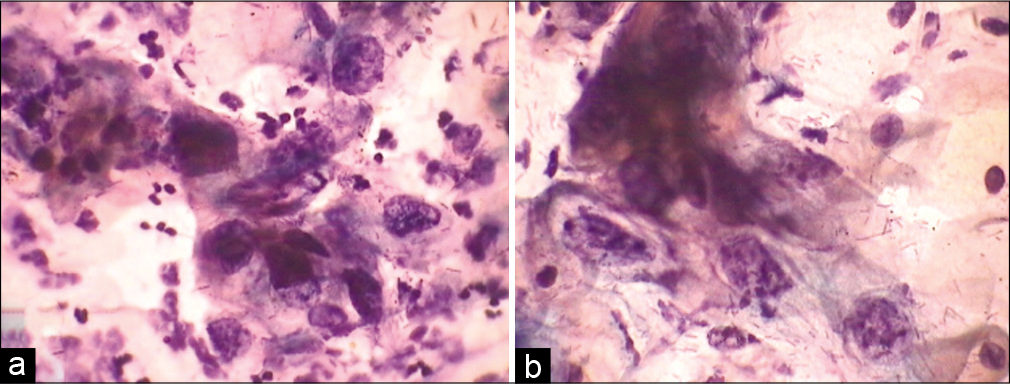

Abnormal appearing nuclei are a prerequisite for the interpretation of ASC. One must be able to see minimal nuclear changes which include hyperchromasia, chromatin clumping, irregularity, smudging, and/or multinucleation [Figure 2a-d]

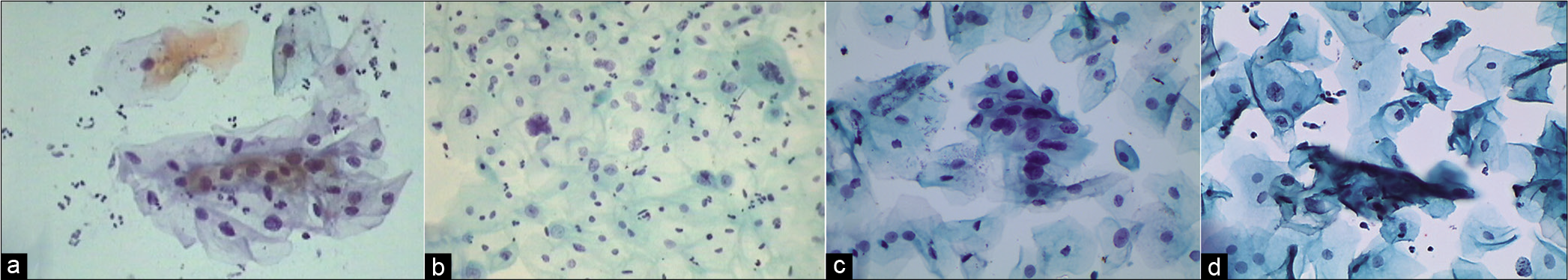

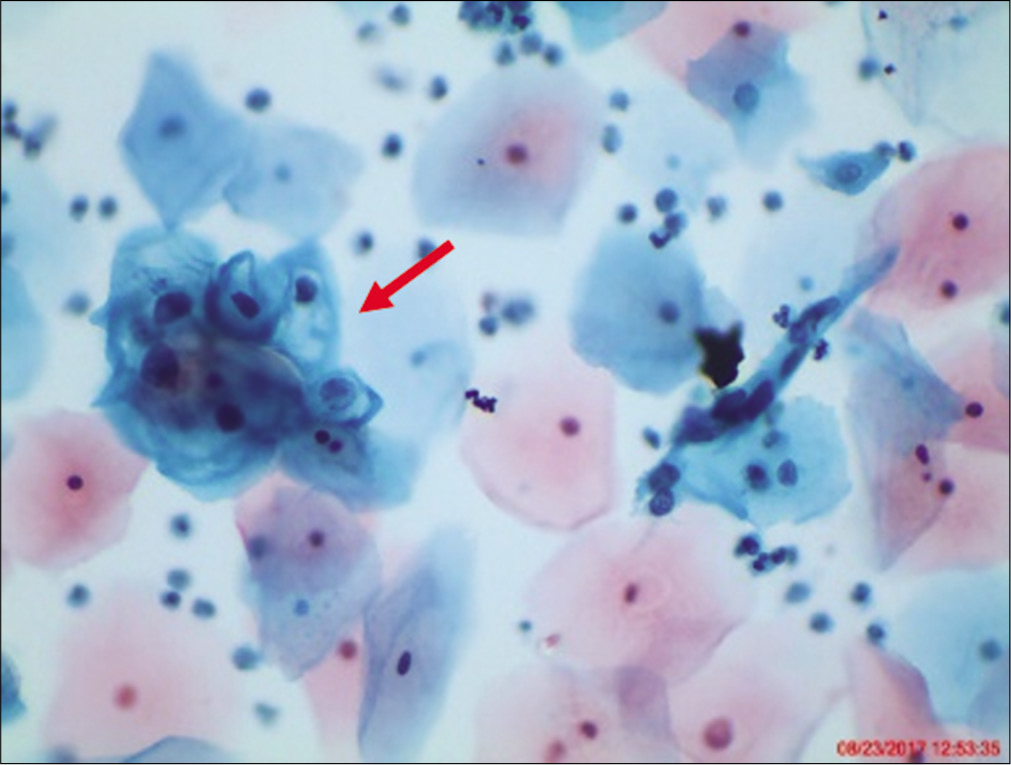

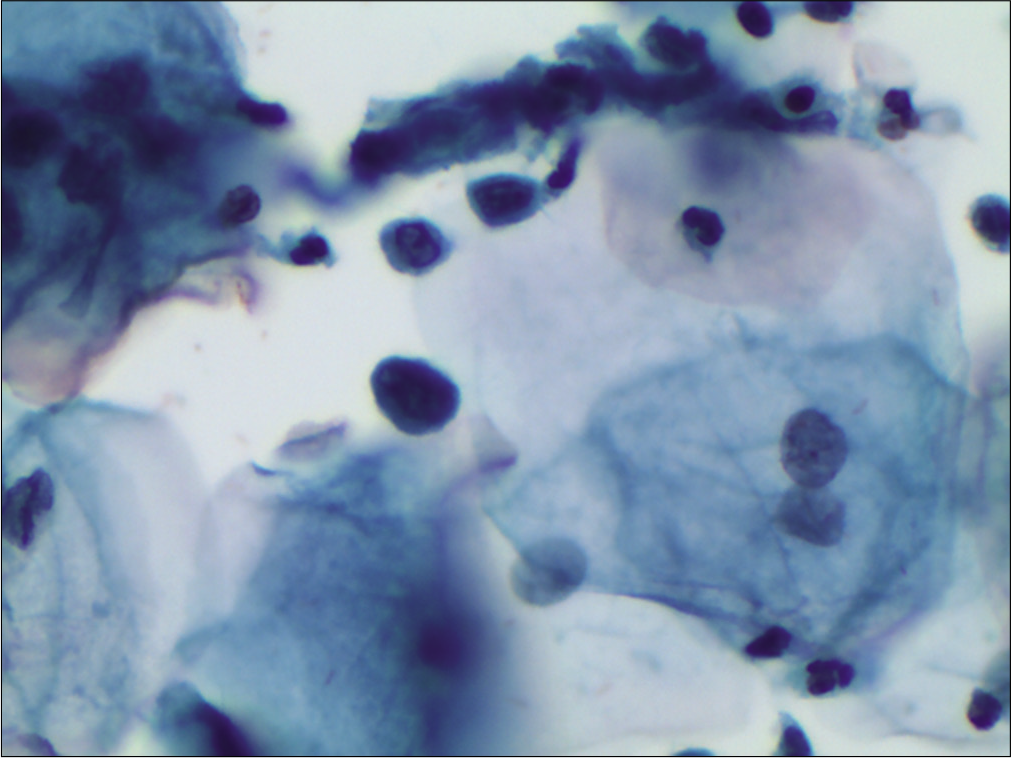

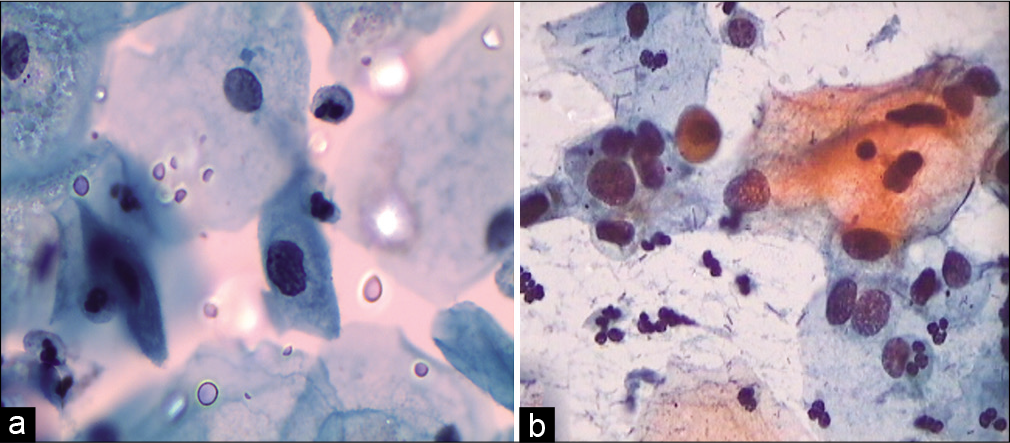

The nuclei may show slight nuclear membrane irregularities [Figure 3] but are often smooth. The classic cytoplasmic and nuclear changes associated with HPV infection (perinuclear halos/koilocytes) warrant an interpretation of LSIL

However, when the changes are incomplete, or in the form of cell plaques with or without perinuclear halos, rafts, and pearls (are commonly scraped from the surface of flat warts) or are suggestive of koilocytosis [Figure 4] (e.g. cytoplasmic halos closely resembling koilocytes but with minimal nuclear abnormalities), or poor preservation of cells, they are generally designated as ASC-US.[26]

When dealing with the metaplastic squamous cells, one needs to make sure that the irregularities are not due to a vacuole pushing the nucleus into the aberrant shape

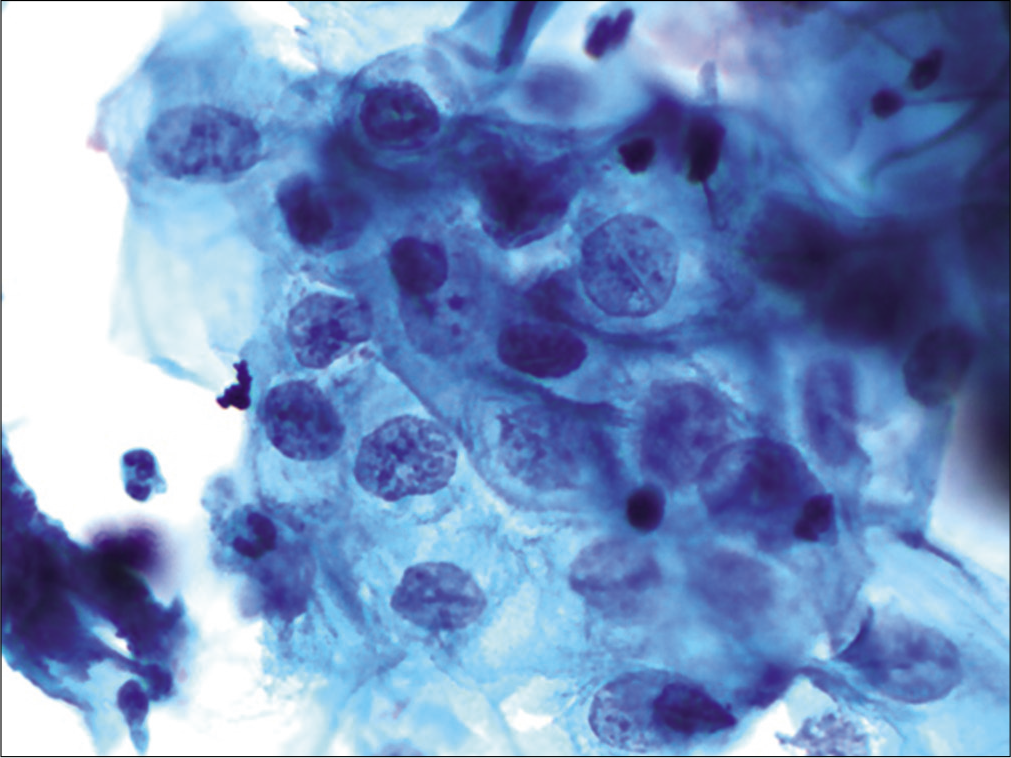

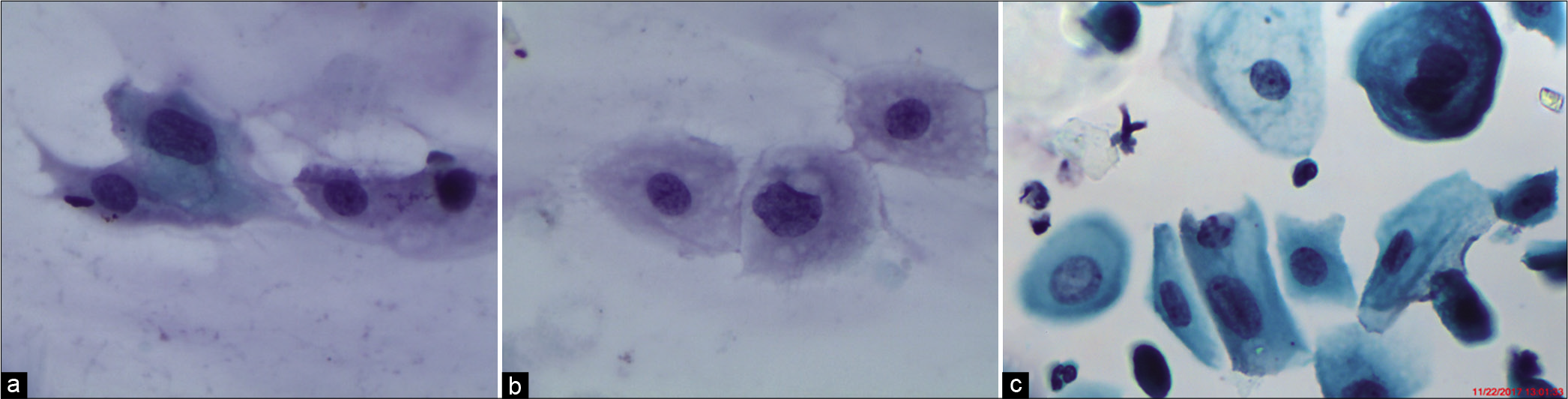

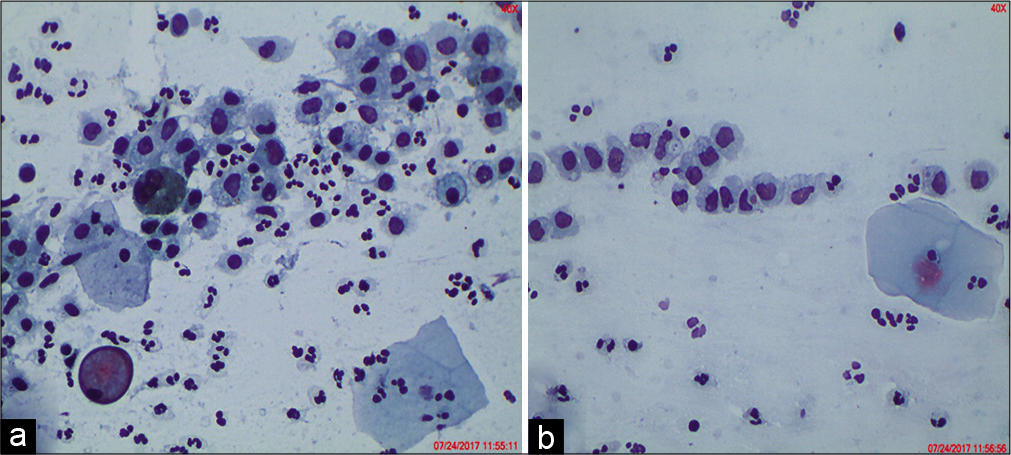

The chromatin pattern is finely granular and evenly distributed [Figure 5a and b]

Chromocenters or nucleoli are generally inconspicuous or absent unless a reactive process is occurring in conjunction with the atypia, at which point, the differential diagnosis of reactive needs to be considered depending on the presence or lack of the other criteria

With either conventional or LBPs, an ASC interpretation may arise from any of the several different cellular changes, including but not limited to, squamous atypia, atypical squamous metaplasia, and atypical parakeratosis. The criteria for ASC-US differ in different types of cells.[13]

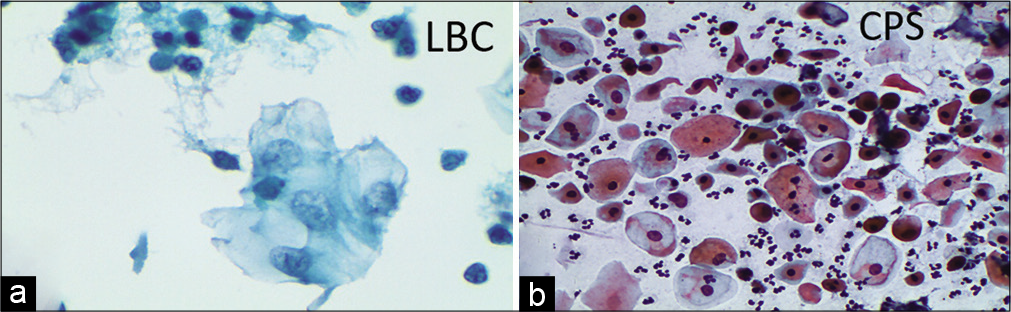

- (a) CP, (b and c) LBC: Increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio (red arrow). The nuclei are slightly enlarged and this enlargement is compared to the unequivocally normal nucleus of the same cell type. Other minimal nuclear changes include hyperchromasia, chromatin clumping, irregularity, and binucleation ×40.

- (a and b) CPS: Nuclear smudging and multinucleation, respectively (×40). (c and d) LBC: Nuclear hyperchromasia and chromatin clumping, respectively (×40).

- LBC: ASC-US. Slight nuclear membrane irregularities in an occasional nucleus (×40).

- LBC smear from a 23-year-old woman. A cluster of intermediate cells is seen with nuclear enlargement 2 − 3 times that of normal intermediate squamous cell nucleus. There is partial haloing of cytoplasm with slight nuclear crenation and hyperchromasia that do not meet the diagnostic criteria for LSIL. A repeat cervical cytology showed similar findings. hrHPV DNA test was positive.

- (a-d) CPS: The chromatin pattern is finely granular and evenly distributed (a and b) (×40). Nuclear size is just about 3–4 times the size of an intermediate cell nucleus. Nuclear membrane is either smooth or slightly irregular (c and d) (×40).

ASC-US with “Mature” Intermediate Type Cytoplasm

Most often, ASC-US involves changes in squamous cells with mature superficial/intermediate-type cytoplasm

Nuclear enlargement is 2.5–3 times the area of a normal intermediate nucleus, (approximately 35 mm2) or twice the size of a squamous metaplastic cell nucleus (approximately 50 μm2).[27] There may be variations in nuclear size. The overall increase in cell size or “cytomegaly” of mature cells with an increase in nuclear size as described favors ASC-US [Figures 1a-c]

The normal-appearing intermediate cells that are present on a slide provide an appropriate source of comparison for assessing whether the nuclear size and appearance meet the criteria for ASC-US or SIL [Figure 1a-c]

Note that the chromatin is finely granular and evenly distributed without significant hyperchromasia

The nuclear membrane is either smooth and or slightly irregular [Figure 5c and d]

When in doubt regarding the nature of cells whether reactive (NILM) or ASC-US, the age of the patient and previous Pap smear reports or reports of hrHPV test, if any, need to be reviewed. It is unlikely to be ASC-US if previous multiple consecutive reports are NILM and or hrHPV test is negative

ASC-US cytology in younger women is more prevalent and more often reflective of an HPV-related lesion than in older women

The prevalence of ASC-US declines with increasing age in the screening population, as does the prevalence of hrHPV DNA (including genotypes 16 and 18)[28]

ASC-US in atrophy

-

Pap test abnormalities are common and also difficult to interpret and report in postmenopausal women. Some points must be kept in mind:

In the menopausal age group, problems such as recovering of scanty material from the overall dry lower genital tract and its lining cells and later artifacts related to smearing of these inherently dry cells (conventional Pap smear) generally lead to overdiagnosis of ASC

“False alarms” are more common in older women than younger ones.[29]

Squamous dysplasia usually occurs in a background of increased maturity, not atrophy

However, carcinoma (in situ or invasive) can be observed with increasing age and in an atrophic background

The prevalence of HPV infection decreases substantially with increasing age. And therefore, HPV DNA triage is significantly helpful in older women[30]

LSILs are uncommon in older women, nevertheless, low immunity levels at this age may be responsible for LSIL

-

And when LSIL does occur, it needs to be investigated properly as it may represent just the “tip of the iceberg” for two reasons.

First, the SCJ that has receded higher up in the canal may not have been sampled completely and

Second, the exfoliation of cells is reduced after menopause.

Challenges in cytomorphologic interpretations

Alarming microscopic findings can occur in atrophy and interpreting these cells may be challenging:

Mild or bland nuclear enlargement during the peri- and post-menopausal phase is common and also a common cause for ASC overutilization

Changes of mild nuclear enlargement without significant hyperchromasia or nuclear irregularity are not generally associated with HPV-related disease

Nucleomegaly and hyperchromasia can be seen in mature cells (intermediate or superficial) and may mimic ASC-US and may result from an accumulation of benign changes occurring with age [Figure 6a-c]

Cells in atrophy may mimic HSIL because of the lack of maturity of the parabasal cells. Even a slight increase in the already high n/c ratio and nuclear chromasia of normal parabasal cells can make it difficult to distinguish them from dysplastic cells. However, the nuclear membranes in benign settings are smooth and uniform. Furthermore, even biopsies can result in a false-negative diagnosis. One has to resort to IHC staining using p16 [Figure 7a-d]

In low-risk scenarios, it may be practical firstly to categorize such atypia as ASC-US rather than ASC-H and also advise adjunctive hrHPV testing to avoid overtreatment

A vast majority (80–90%) older women with minimal cytologic abnormalities (ASC-US like changes) have negative colposcopic or biopsy findings and a negative hrHPV DNA test

To qualify as a true LSIL, cells in an atrophic smear must show significant nuclear enlargement with concomitant hyperchromasia, abnormal chromatin texture, irregular chromatin distribution, marked irregularities in nuclear contour, and/or marked nuclear pleomorphism as spindle or tadpole cells

Still, if diagnostic dilemmas persist, a short course of local application of estrogen (1 g estrogen cream – local application for 1 week), followed by a repeat Pap smear, a week after completing the regimen will be useful to clarify the diagnosis. The “hormonally deaf ” abnormal epithelial cells will persist and will stand out against the normal cells undergoing maturation and differentiation.

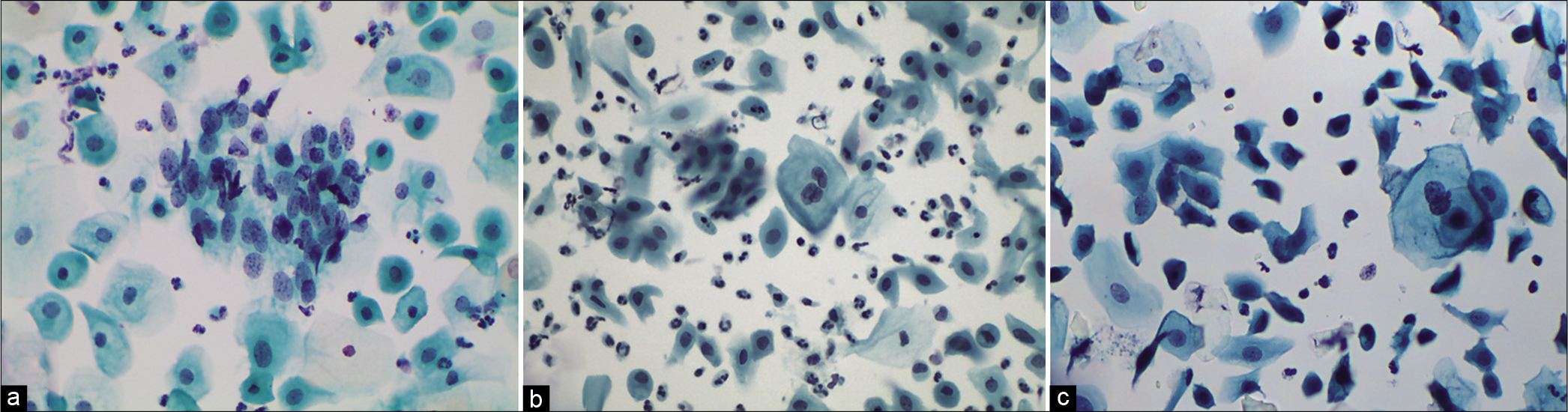

- (a-c) LBP. ASC-US in atrophy. Multinucleation, nucleomegaly, and hyperchromasia can be seen in mature cells (intermediate or superficial) and may mimic ASC-US. Mild nuclear enlargement without significant hyperchromasia or nuclear irregularity (a) (×40).

- (a) CPS: Deep parabasal and basal cells being scraped from thinned out atrophic epithelium can mimic cells of HSIL (×40). (b) LBC: Smear showing granular muck in the background, typically seen in an atrophic smear, with hyperchromatic parabasal cells, should not be confused with HSIL and necrosis (×40) (c) (H and E stain) showing SCJ and a thin layer of parabasal cells with high N/C ratio creating suspicion of HSIL. (d) IHC of the same for p16 which is negative (×40).

ASC-US in metaplastic squamous cells

-

Inflammation and repair go hand in hand. The NILM smears often display squamous metaplastic cells

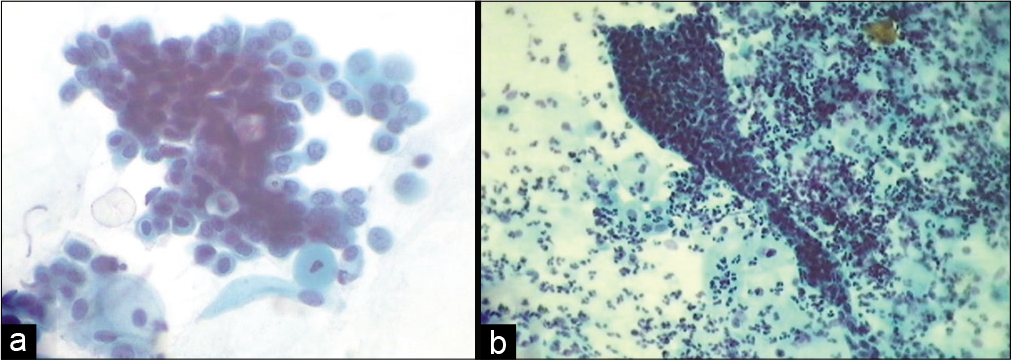

Metaplastic cells showing some degrees of cellular overlap, dyscohesion, anisonucleosis, and/or loss of nuclear polarity may be designated as “atypical repair” which is a degree beyond “reactive and reparative” changes seen in a NILM smear. Occasionally, a mitosis may be seen [Figure 8a]

Round or ovoid cells that are approximately one-third the size of superficial cells and therefore resemble large metaplastic or small intermediate cells may also be classified as ASC-US. In LBP, the cells may appear smaller and rounder compared to conventional smears [Figure 8b and c]

In favor of a reactive process are the generally fine granularity of the chromatin pattern and the fact that most nuclei show prominent nucleoli

The atypical repair can be classified under the ASC-US category when the nuclear abnormalities are at the lower end of the spectrum [Figure 8c]

However, in immature squamous metaplasia, the increased nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio is more important than nuclear enlargement [Figure 9a-c]

Cytologic features that are favoring the possibility of invasive carcinoma, especially in high-risk patients, should be placed in the ASC-H category.

The incidence of subsequent SIL among women with atypical repair has been reported to range from 25 to 43% in high-risk population groups; however, the incidence of SIL in a more diverse population has been shown to be much lower (5.2%)[31]

- (a-c) LBC: Immature metaplastic cells with nuclear atypia favoring atypical repair. (×40). (a) Mitotic figure (red arrow), (b) nuclear enlargement and inflammatory cells overlapping metaplastic cells favor a reactive process, (c) smaller and rounder metaplastic cells in atypical repair (×40).

- (a-b) CPS: Immature metaplastic cells showing high N/C ratio (×40). (c) LBC: Features of ASC-US in little more mature metaplastic cells. Nuclear enlargement and binucleation are seen (×40).

ASC-US in parakeratotic squamous cells

Parakeratotic cells with small pyknotic normal-looking nuclei fall in the category of NILM

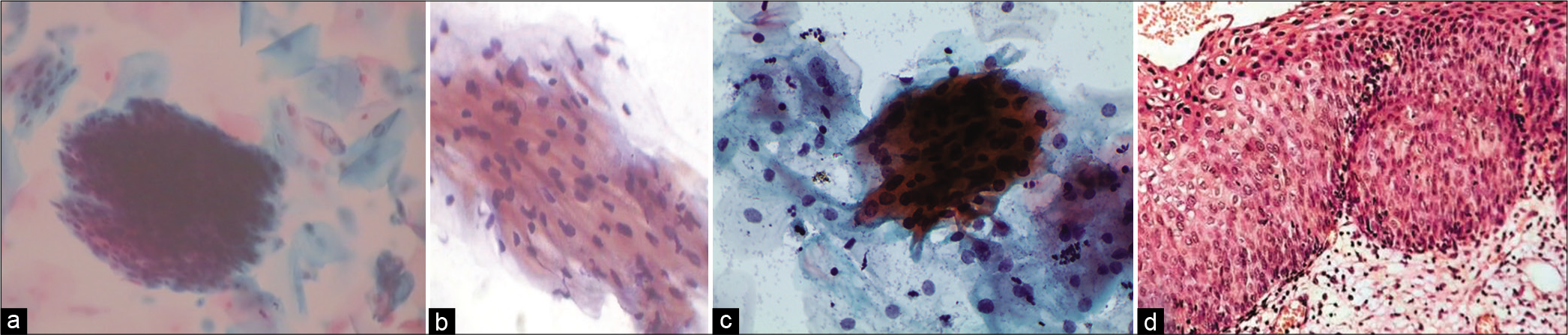

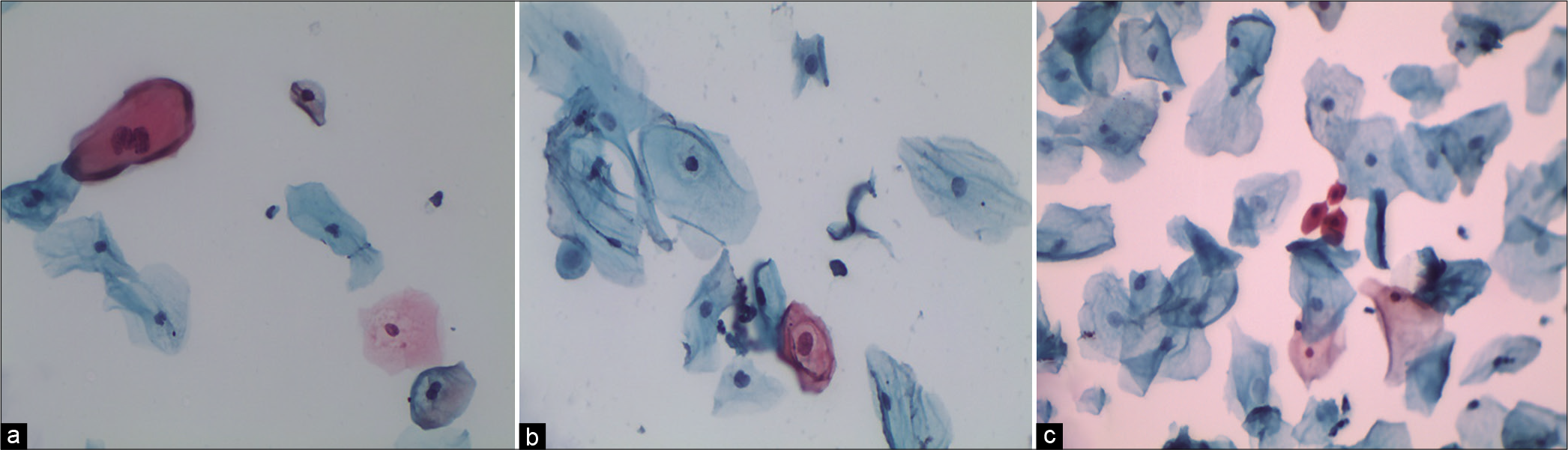

However, the same cells, with enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei with irregularities of the nuclear membrane (also known as atypical parakeratosis) are seen either singly or in three-dimensional clusters. They have dense eosinophilic or orangeophilic cytoplasm, cellular pleomorphism, some with an increased nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, and dark irregularly distributed chromatin [Figure 10a-c]

The presence of anucleate squamous cells singly or in plaques or cakes (hyperkeratosis), atypical parakeratosis, and dyskeratosis [Figure 11a-c] are non-classic features of HPV infection. They generally cover the surface of warts. Cell plaques with or without perinuclear halos, rafts, and pearls are commonly scraped from the surface of flat warts

If any two of these non-classic cytologic features are recognized and also depending on the degree of abnormalities, interpretation of ASC-US, ASC-H, or SIL must be considered.[26,32]

If not liberally, judicious use of ASCUS as a diagnostic category significantly improves the clinical usefulness of the Pap test. At times in a biopsy [Figure 10d], the atypical parakeratotic layer may camouflage a more ominous lesion beneath it and therefore colposcopic evaluation and directed biopsies of flat warts/leukoplakia cannot be overemphasized.

- (a and c) LBC. (b) CPS. Atypical parakeratotic cells qualify for ASC category. Smears showing stacks of miniature mature keratinized cells with pleomorphic nuclei (×40). (d) Tissue biopsy showing pleomorphic parakeratotic cells camouflaging the underlying HSIL (×40).

- LBC (a) Smear showing dyskeratotic cell with binucleation. (b) Single dyskeratotic cell with partial haloing of cytoplasm. (c) Dyskeratotic cells with dense pyknotic nuclei (×40).

ASC-US due to compromised specimen

Poor fixation, obscuring material, or drying artifacts in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women compromise visualization and evaluation of cellular changes. In such cases, a repeat smear or other follow-up should be emphasized in the report. Vacuolar degeneration of the cytoplasm may mimic koilocytes. Nuclear features also show degenerative changes in the form of smudging or nuclear vacuolation [Figure 12a and b].

- (a) LBC – Poor preservation of cells. (a) Vacuolar degeneration and pale enlarged degenerated nuclei. (b) CP – Drying artifact, leading to polychromasia and dark staining of the nucleus, in a CPS from a case of atrophy. Such smears may be falsely labeled as ASC-US (×40).

Summary

• Morphologic criteria of ASC-US

Cells are the mature squamous type or mature metaplastic type

Cells present predominantly singly and in few sheets

Nuclei are 2.5–3 times the size of a normal intermediate cell nucleus or 1.5–2 times the size of a normal metaplastic cell nucleus

There is a slight increase in the nuclear-tocytoplasmic ratio

Nuclear membranes are smooth to slightly irregular

Chromatin is finely granular and evenly distributed.

Nucleoli/chromocenters are inconspicuous or absent.

Non-classic HPV cytopathic effects and/or binucleation may suggest HPV changes, but fall short of LSIL diagnosis

Binucleation accompanies HPV, but also can be from a reactive process

Atypical parakeratosis may present with minimal cellular pleomorphism, a slight increase in nuclear size, and dark chromatin

Atypical more mature metaplastic cells may show slightly increased N/C ratio, slight nuclear membrane irregularities, and slight hyperchromasia.

• Differential Diagnosis of ASC-US

Reactive changes versus LSIL

Pseudokoilocytosis due to reactive change as in Trichomonas infection, Candida infection, artifacts, glycogen, or degeneration

Perimenopausal changes are like generalized increase in the size of intermediate cells, increased nuclear size with minimal hyperchromasia without an increase in N/C ratio.

• The burden of disease in ASC-US

Individual’s risk of high-grade SIL is 15–30%

Approximately 33–50% of HSIL occurs in women with ASC Pap results

However, an individual’s risk of cancer is only about 1:1000

• ASC-US: Quality Control

ASC is a diagnosis of exclusion

In a normal population, it should not exceed 5%

ASC-US: SIL ratio should not be more than 2:1

By ALTS data: 50% of ASC-US show hrHPV positivity

• Quality Assurance

Calculation of ASC-US/SIL ratio

Correlation of ASC-US cases with hrHPV positivity rates. Review by second cytotechnologist and/or cytopathologist

Correlation of ASC-US cases with the results of colposcopically directed biopsy.

• hrHPV-positive rates and ASC-US

A consistent relationship between hrHPV detection and TBS diagnostic criteria is observed.[33]

hrHPV types were detected in 10% of negative smears, 30% of ASCUS, and 60% of SIL specimens

Most recent HPV Q-Probe data conclude that a hrHPV-positive rate is 43.7% in patients reported as ASC

In other studies, the median rate is reported as 34.1%–50.6%, depending on the age of the population studied.

• Management/Follow-up protocols of ASC-US

The preferred approach for the evaluation of women ages 25 or older, with ASC-US cytology, is testing for high-risk types of HPV with triage of women who test positive to colposcopy

The use of HPV testing to triage further evaluation of ASC-US is the most effective strategy for detecting high-grade premalignant disease or cervical cancer

Reflex HPV testing has the additional advantage that it saves the patient from the inconvenience of a second visit for HPV testing. This is possible only when cervicovaginal cells are collected in a LBC vial. This vial can be immediately sent for HPV DNA testing

Repeat cytology in 1 year is a reasonable alternative if HPV testing is not available

Colposcopy is performed if repeat cytology shows ASC-US or a more severe cervical abnormality

For women ages 21–24 years with ASC-US cytology, repeat cytology at 12 months rather than reflex HPV testing is advised.

CLINICAL MANGEMENT OF ASC

Estimates of the prevalence of invasive cancer in women with ASC is as low as 0.1–0.2%

Prevalence of CIN 2 / 3 in women with ASC-H is estimated to be around 37–40% than in those with ASCUS (11%).[34,35.36]

Therefore, it is necessary that, the women with Pap smear reported as ASC-H undergoes colposcopy and those with a report of ASC-US undergoe hrHPV DNA testing.

ASC-cannot rule out HSIL (ASC-H)

ASC-H is a designation reserved for the minority of ASC cases (<10%), in which the cytology changes are suggestive of HSIL.[15] This reporting category should be used carefully and sparingly

Only equivocal specimens specifically worrisome of HSIL should be distinguished from the bulk of ASC

Cases classified as ASC-H are associated with a higher predictive value for detecting an underlying CIN2 or CIN3 than ASC-US

It warrants immediate colposcopy to confirm or exclude the presence of HSIL. ASC-H does not represent single biologic entity

It subsumes changes related to oncogenic HPV infection and neoplasia as well as findings that suggest the possible presence of CIN and rarely carcinoma

Studies show 35–50% of women with ASC are infected with hrHPV, and the remaining non-infected women are not at increased risk

The nuclear changes are mainly noted in the immature metaplastic cells.

Cytomorphology

ASC-H usually affects immature squamous metaplastic cells

ASC-H is defined as “changes suggestive of/or cannot rule out a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion”

The atypical cells are either quantitatively or qualitatively insufficient for a definitive interpretation. More often than not, inadequate number of atypical cells is usually the reason for an ASC-H interpretation. Only a few cells with equivocal features of high-grade dysplasia will be present

-

The cells are arranged either singly or in loose cohesive groups or in cohesive overcrowded groups. The different patterns are:

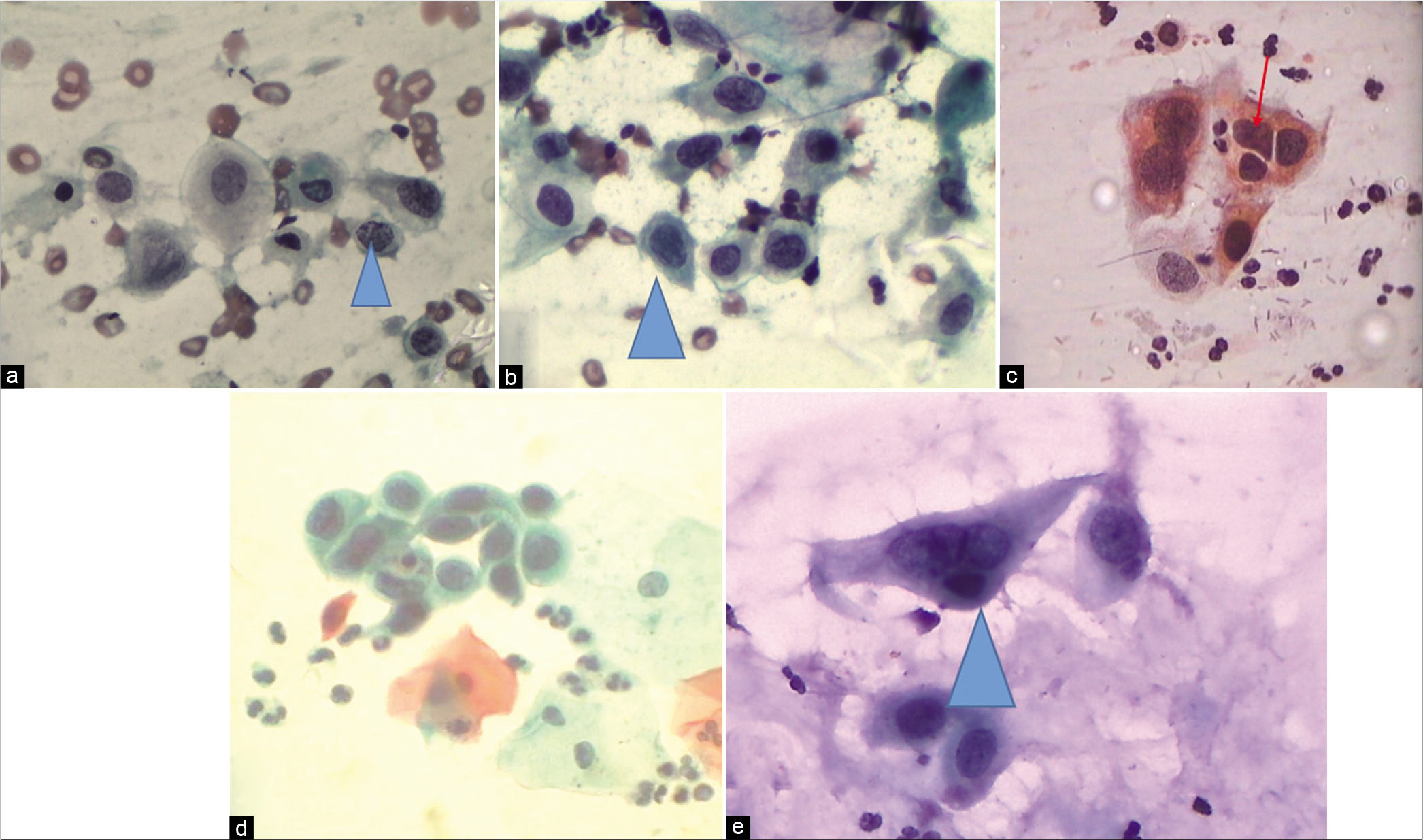

Small cells with high N/C ratios: “Atypical (Immature) Metaplasia” [Figure 13a-d]

Immature squamous metaplasia is one of the most common mimics of ASC-H

An interpretation of ASC-H is appropriate, especially when only rare abnormal cells with “metaplastic” cytoplasm and high N/C ratio are present

Single or small fragments of less than 10 cells may stream in mucus

ASC-H cells demonstrate nuclear enlargement at least 1.5–2.5 times of metaplastic cells

In addition, high N: C ratio, coarse chromatin pattern, as well as some degree of hyperchromasia, abnormal nuclear shapes, and nuclear membrane irregularity favor HSIL over benign metaplasia

In LBPs, the metaplastic cells are seen mostly singly and are round with high N/C ratio and hyperchromatic nuclei [Figure 14a-c]

Sometimes, cells may show all features of HSIL, but the number of such abnormal cells is so less that the microscopist who is fully aware of the repercussions of his/her report is unable to sign out confidently a diagnosis of HSIL [Figure 15a and b]

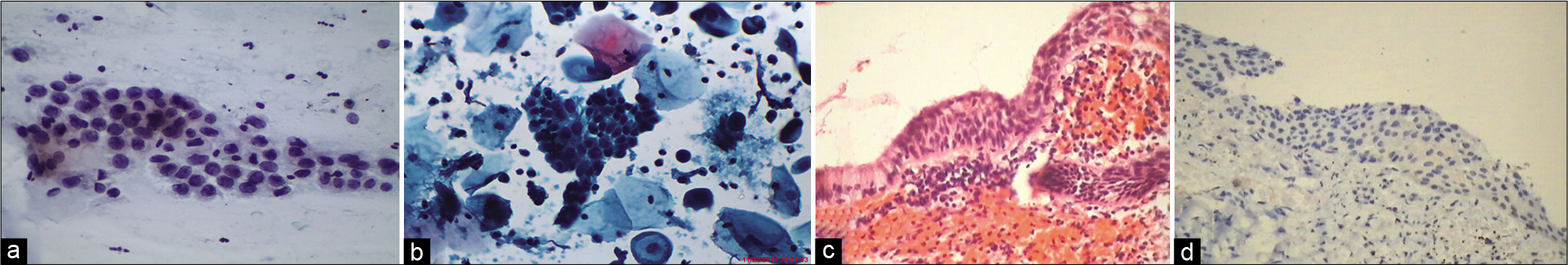

- CP – Examples of cells labeled as ASC-H. (a) Single cell at the arrow is showing high N/C ratio, hyperchromatic nucleus, and coarse chromatin. (b) Significant nuclear enlargement (1.5–2 times that of a normal metaplastic cell) with atypia. (c) Nuclear enlargement, abnormal nuclear shapes, and hyperchromasia of metaplastic cells. (d) Sheet of highly atypical metaplastic cells. However, sharp cytoplasmic outlines such as intercellular junctions as against syncytial clusters of HSIL are seen. Therefore, ASC-H is an appropriate interpretation (×40). (e) ASC-H in a metaplastic squamous cell.

- (a-c) LBC smear from a 36-year-old woman. Single small round immature metaplastic cells. Cells are the size of metaplastic cells with nuclei that are about 1.5–2.5 times larger than normal (×40).

- (a and b) CPS. Single small cells with nuclear features favoring HSIL but their number are very less in the smear also known as “litigation cells.” Such cells have been picked by automated screening devices (×40).

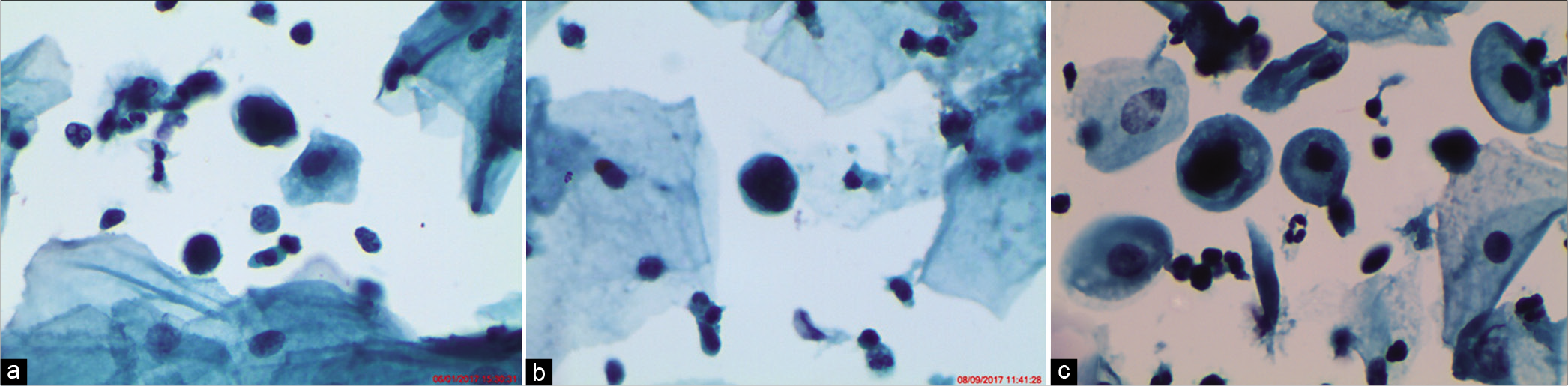

1. Crowded Sheet Pattern or Hyperchromatic crowded cell groups (HCGs)

This pattern consists of a crowded group of cells containing nuclei with loss of polarity. Cellular and nuclear details are difficult to visualize [Figure 16a-c]

These HCGs may result either from a true HSIL or because of vigorous scraping with sampling devices (brushes and brooms), and this represents an avoidable cause of thick cell fragments. The thickness of the cluster makes it difficult to determine if the cells are reactive or neoplastic

In an inflammatory or reactive process, the cells within the cluster often include acute inflammatory cells. And second, the presence of nucleoli is more indicative of a reactive than neoplastic process [Figure 17a-d]

The tips of sampling device may also scrape cells from the glandular crypts in cases with cervical erosions. In this situation, the differential diagnosis of hyperchromatic crowded cell groups includes reactive or neoplastic endocervical cells. Also included are atrophy or endometrial cells [Figure 18a and b]

In an attempt to interpret a crowded cluster of cells, first try and identify whether the cells are of squamous or of glandular origin

The features in favor of squamous over glandular differentiation are streaming of nuclei within the cluster, dense cytoplasm, polygonal shape, and fragments with sharp linear edges [Figure 18b]

In case, the cells favor a glandular origin then the differentials include endocervical carcinoma in situ, endocervical carcinoma, HSIL, or HSIL involving glands

In LBPs, the ASC-H cells are usually sparse. The cells are very small and seen mostly singly. The nuclei of these cells are around 2–3 times the size of neutrophils [Figure 19]

In atrophy, at times, the parabasal cells show features suggestive of HSIL like increase in N/C ratio and hyperchromasia but when there is regular pacing between the cells and nuclear outlines are smooth, an interpretation of ASC-H may be appropriate. HPV DNA test and follow-up colposcopy in postmenopausal women are more often negative as compared to younger women [Figure 20a-c]

Rare metaplastic cells with dense cytoplasm and nuclear enlargement with hyperchromasia are present in a background of scattered acute inflammation

Degeneration of nuclei may be the source of confusion. But note that degenerated nuclei, in the absence of a bona fide SIL, are often irregular or hyperchromatic, but the irregularities tend to involve the entire nuclear outline, imparting a wrinkled appearance, and the chromatin is smudgy[37]

- ASC-H. (a) Hyperchromatic crowded groups (HCGs) seen in an LBC preparation show crowded group of cells containing nuclei with loss of polarity (×10). (b) Cellular and nuclear details are difficult to visualize but are seen in peripheral cells only creating a suspicion of HSIL. (c) Vigorous scraping with sampling devices (brushes) represents an unavoidable cause of thick cell fragments. The thickness of the cluster makes it difficult to determine if the cells are reactive or neoplastic (×40).

- (a-d) CPS (×40) – Immature metaplastic cells in a reactive process show nucleoli, smooth membranes (a and b), and inflammatory cells either engulfed by these reactive cells. (c) Follow-up colposcopy. (d) Thick metaplastic islands around glandular openings and there was no evidence of CIN lesion.

- (a and b) CPS: (a) Cells in a crowded pattern at a glance resembling endocervical cells but are actually deep basal and parabasal squamous cells with dense cytoplasm and mild-to-moderate nuclear atypia. (b) HCG favoring reactive glandular cells.

- LBC – Small single cells creating a suspicion of HSIL because of high N/C ratio, thick nuclear membrane, and hyperchromasia. Such few single cells without any syncytial clusters in rest of the smear qualify for an ASC-H (×40). HPV DNA test was positive in this patient. However, the patient did not turn up for colposcopy.

- (a-c) CPS – ASC-H in atrophy. Parabasal cells showing features suggestive of HSIL like increase in N/C ratio and hyperchromasia but there is regular pacing between the cells and nuclear outlines are smooth (×40). A diagnosis of ASC-H may be appropriate. Follow-up colposcopy (b and c) favored a HSIL.

2. SIL grade cannot be determined

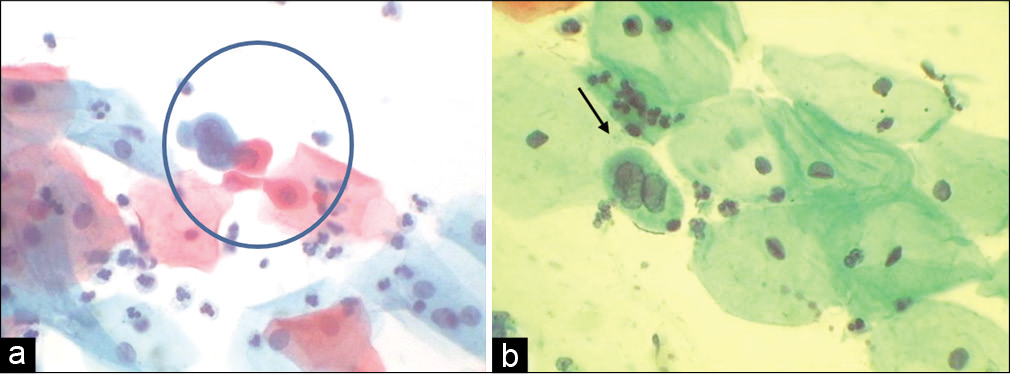

At times, there is marked nucleomegaly seen in HPV infection and one is unable to gauge the cytoplasmic maturity. This can be confusing whether to label it as LSIL or HSIL. Commonly HPV is associated with CIN I, but the exuberant nucleomegaly may be comparable with CIN II [Figure 21]. In such a situation take into consideration, the overall cytomegaly when calculating the N/C ratio rather than the size of nucleus alone – because there are differences in management and follow-up protocols of women with LSIL and HSIL

When the cytologic features are between LSIL and HSIL and if it indicates that definite LSIL is present as well as some cells are suggestive of the possibility of HSIL, in such cases, 2014 Bethesda recommends that instead of overcalling of CIN grade, one can give an interpretation of ASC-H in addition to LSIL interpretation [Figure 22a and b][38,39]

- (a and b) CPS. SIL grade cannot be determined. (a and b) HPV may be associated with exuberant nucleomegaly which enables one to gauge the maturity of the cell. Furthermore, the nuclei are highly pleomorphic. This was a pregnant woman, cervix was unremarkable, so after seeing this smear we did her HPV DNA testing and it was positive for high-risk viruses. Colposcopy showed features of LSIL.

- (a and b) SIL, grade cannot be determined. Cells of LSIL and few suggestive of HSIL are seen. Instead of overcalling of CIN grade, one can give an interpretation of ASC-H in addition to LSIL interpretation.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Repair – Identification of prominent nucleoli is more typical of repair. In “atypical repair,” cells can be immature metaplastic cells or glandular cells. They differ from the typical “repair” by the presence of considerable nuclear crowding in loosely cohesive groups, anisonucleosis, uneven chromatin distribution, irregular nuclear contours, and irregular nucleoli [Figure 17]

Atrophy – Application of topical estrogen for 1 week, followed by repeat smear after 1 week will result in maturation of cells

Radiation change – Typical benign radiated cells show proportionate nuclear and cytoplasmic enlargement. Degenerative changes are seen in both cytoplasm and nucleus

Non-neoplastic entities that may be interpreted as ASC-H include histiocytes degenerated endometrial cells, atrophic parabasal cells, and cells in patients wearing an intrauterine device [Figure 23]

Invasive carcinoma: The lack of single atypical cells and clean background would favor a reactive process or SIL depending on the nuclear features of cells in question

The presence of frank cellular necrosis favors neoplasm.

- (a and b) Histiocytes can be confused and labeled as ASC/ASC-H.

BURDEN OF DISEASE IN ASC-H

ASC-H is associated with higher risk of oncogenic HPV DNA detection and greater risk of underlying CIN2 or worse (30–40%) compared to ASC-US (10–15%).

MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES

HPV testing is not recommended for triage of ASC-H

The recommended management of ASC-H is colposcopy[22]

-

Management of women with ASC-H and colposcopy that does not result in histologic diagnosis of CIN2 or more severe lesion should be individualized based on review of all pathologic or clinical findings

Careful follow-up is required either with HPV testing at 12 months

Or cytology testing at 6 and 12 months is recommended.[17]

In contradistinction to definitive interpretation of HSIL, immediate treatment without colposcopy is not possible.

SUMMARY

ASC is the product of limitations of light microscopy and diagnostic capabilities. It also conveys the uncertainty of gynecologic cytology. At the same time, it provides a comfort level to the reporting pathologist. ASC tends to decrease with experience and interestingly will increase with lack of experience and fear of missing abnormal lesions.

There are many criticisms for ASC category. The major one is its subjective and inconsistent applications. Low interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility is evidenced in many studies. However, studies have shown that if we eliminate ASC-US, the LSIL rate will increase. If ASC-H is eliminated, the chances of detecting true lesions are reduced. Hence, there are strong reasons to retain ASC category. As cervical carcinogenesis is a continuum process, there is no sharp dividing line between different categories. Now, ASC category is well accepted and widely used by cytologist and is much familiar to clinicians.

Acknowledgment

Sincere thanks to Dr. Prajakta Sathawne for her assistance in the editing and completion of this chapter.

ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

ASC - Atypical Squamous cells

ASC-US - Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

ASC-H - Atypical Squamous cells cannot rule out high grade lesion

TBS - The Bethesda System

HPV - Human papilloma virus

DNA - Deoxyribonucleic acid

Pap – Papnicolaou

LSIL - Squamous Intraepithelial lesion

HSIL - High grade Squamous Intraepithelial lesion

CIN - Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

SIL - Squamous Intraepithelial lesion

HCGs - Hyperchromatic crowded groups

NILM - No Intraepithelial Lesion or Malignancy

N/C - Nuclear Cytoplasmic ratio

LBC - Liquid based cytology

LBPs - Liquid based preparations

LSIL - Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

N/C - Nuclear/Cytoplasmic ratio

hrHPV - High risk Human Papilloma Virus

References

- Koss’ Diagnostic Cytology and Its Histopathologic Bases (5th ed). Pennsylvania, United States: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histologic types and prognosis of cervical cancer of uterine cervix. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1979;5:1015.

- [Google Scholar]

- The new Bethesda system for reporting results of smears of the uterine cervix. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:988-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Bethesda system 2001: Update on terminology and application. Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;48:98-107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bethesda 2001: Science, technology, and democracy join forces for patient care. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;26:135-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Bethesda system 2001: An update of new terminology for gynecologic cytology. Clin Lab Med. 2003;23:585-603.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Pap test and Bethesda 2014 “The reports of my demise have been greatly exaggerated” (After a quotation from Mark Twain) Acta Cytol. 2015;59:121-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- for the forum group members and the Bethesda 2001 workshop. The 2001 Bethesda system-terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287:2114-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology (2nd ed). New York: Springer; 2004.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Bethesda system for reporting cervical cytology: Definitions, criteria Vol Ch. 4. (2nd ed). Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2004. p. :67-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interobserver reproducibility of cervical cytologic and histologic interpretations: Realistic estimates from the ASCUS LSIL triage study. JAMA. 2001;285:1500-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology (3rd ed). Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2015. p. :103-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identifying women with cervical neoplasia: Using human papillomavirus DNA testing for equivocal Papanicolaou results. JAMA. 1999;281:1605-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Testing for human papillomavirus: Data driven implications for cervical neoplasia management. Clin Lab Med. 2003;23:569-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Results of a randomized trial on the management of cytology interpretations of atypical squamous cells of undetermined signifi cance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1383-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Bethesda system for reporting cervical cytology In: Bibbo M, Wilbur DC, eds. Comprehensive Cytopathology (4th ed). London: Elsevier; 2015.

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural history of cervicovaginal papillomavirus infection in young women. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:423-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Update on ASCCP consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical screening tests and cervical histology. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:147-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:829-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiologic evidence showing that human papillomavirus infection causes most cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:958-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- ASCUS-LSIL triage study: Design, methods and characteristics of trial participants. Acta Cytol. 2000;44:726-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural history of cervical intraepithelial lesion: A meta-analysis. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:405-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benign proliferative reactions, intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive cancer of the uterine cervix In: Bibbo M, Wilbur DC, eds. Comprehensive Cytopathology (4th ed). London: Elsevier; 2015.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benign proliferative reactions and squamous atypia of the uterine cervix In: Wied GL, Bibbo M, Keebler CM, Koss LG, Pattern SF, Rosenthal DL, eds. Compendium on Diagnostic Cytology (8th ed). Chicago: Tutorials of Cytology; 1997. p. :81-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The interplay of age stratification and HPV testing on the predictive value of ASC-US cytology: Results from the ATHENA HPV study. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137:295-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical significance of cytologic diagnosis of atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high grade, in peri-menopausal and post-menopausal women. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126:381-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review of histological outcomes from peri-menopausal and post-menopausalwomen with a cytological report of possible high-grade abnormality: An alternative managementstrategy for these women. Pathology. 2010;42:23-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atypical repair on pap smears: Clinicopathologic correlates in 647 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2005;33:214-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histopathologic correlation of atypical parakeratosis diagnosed on cervicovaginal cytology. Acta Cytol. 2003;47:405-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toward objective quality assurance in cervical cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:182-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Qualification of ASCUS: A comparison of equivocal LSIL and equivocal HSIL cervical cytology in the ASCUS LSIL triage study. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;116:386-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade intraepithelial lesion. Diagnostic performance human papilloma virus testing, and follow up results. Cancer Cytopathol. 2006;108:32-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL: LSIL, HSIL, ASCUS, ASC-H, LSIL-H) of Uterine Cervix and Bethesda System. CytoJournal. 2021;18:16.

- [Google Scholar]

- ASC-H in Pap test--definitive categorization of cytomorphological spectrum. Cytojournal. 2006;3:14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Should LSIL with ASC-H (LSIL-H) in cervical smears be an independent category? A study on SurePath specimens with review of literature. Cytojournal. 4:7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Twilight zone in high grade cervical cytology (ASC-H, LSIL-H) & future trends in cervical cytology in general Ch 18,249-261 In Usha Saraiya & Giovanni Miniello, ed. Cytology and Colposcopy in Gynaecological Practice (2nd Edition). St Louis: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2008.

- [Google Scholar]