Translate this page into:

The Pap smear in inflammation and repair

*Corresponding author: Meherbano M. Kamal, Department of Pathology, Government Medical College, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India. dr.mmkamal@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Kamal MM. The Pap smear in inflammation and repair. CytoJournal 2022;19:29.

Abstract

Cytology of the uterine cervix is one of the most widely utilized tests and is best known primarily for the cytologic changes seen in precancerous lesions and invasive cancer of the uterine cervix. The more common inflammatory conditions of cervicitis and vaginitis are close clinical differentials, especially when they give rise to excessive blood-stained vaginal discharge. These infective conditions also result in variation in the appearance of otherwise benign squamous and glandular cells in cervical cytology specimens. A variety of physiologic and pathologic conditions are responsible for the conversion of polymicrobial flora of the vagina to a monomicrobial one. The latter may overgrow the others and result in inflammation of the cervix and the vagina. Chronic irritation of the cervix due to intrauterine devices, chemical irritants, inflammation/infection, endocrine changes, and reparative changes can lead to worrisome parakeratosis, hyperkeratosis, and squamous metaplasia of non-keratinized squamous mucosa of the cervix and the vagina and may mimic HPV-related changes. Although some benign changes are specific for certain infections, for example, Trichomonas infestation, most of the reactive and hyperplastic cell morphology are important to recognize only due to the significant morphologic overlap with neoplastic changes in cytology specimens. Identification of different pathogens specifically may not be relevant from a clinical point of view, but is undoubtedly a cytologists’ privilege to inform the clinician! This chapter describes in detail the cytoplasmic and nuclear reactive changes that are found in specific and non-specific inflammatory conditions. In addition, diagnostic pitfalls are emphasized where necessary.

Keywords

Inflammatory atypia

Reactive endocervical cells

Morphology of florid squamous metaplasia

Squamous epithelial cell changes in inflammatory conditions

The mucosa of the vagina and the cervix is in continuity. Both are, therefore, exposed to a similar risk of infection. Many, although not all, of the infectious organisms causing inflammation, are generally transmitted sexually. A good general state of health, a competent immune system, an intact squamous epithelium, an acidic pH of the vagina, and the equilibrium between the various microorganisms normally present as commensals are responsible for the natural protection from various infections.[1,2] Therefore, infections from outside or the commensals becoming pathogenic happen when:

The squamous epithelium of the vagina and cervix is not fully mature and also when the thickness is less, such as that seen in prepubertal girls or menopausal women

Or when the epithelium is traumatized especially during pregnancy or delivery.

When there are variations of the vaginal pH from acidic to neutral or alkaline. In the course of the menstrual cycle, the pH varies from 6.8 during menstruation to 3.9 during the second half of the cycle

When the endocervical and the squamous epithelia meet outside of the external os (known as ectropion, eversion, or also misnamed as erosion). This is a red patch lined by the delicate endocervical glandular epithelium which is easily penetrated by bacteria

A rapid increase in microorganisms due to poor perineal hygiene is one of the most common factors responsible for sexually transmitted infections.

CLINICAL FEATURES OF INFECTION

Both acute and chronic infections of the vagina and the cervix may cause excessive vaginal discharge (leukorrhea) which may be discolored or blood-stained. The discharge may be foul-smelling. Itching and burning in micturition are other common symptoms. Irregular and/or excessive menstrual bleeding and lower abdominal pain are noted especially when the infection ascends into the endometrium, leading to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).[3]

INFLAMMATION AND INFLAMMATORY CHANGES (INFLAMMATORY ATYPIA)

Inflammatory changes can have many features in common with dysplasia. Distinguishing one from the other is a common day-to-day problem in Pap smear interpretation.[4] To begin with, it is important to know that, rather than destroying the squamous and glandular cells, acute or chronic inflammation, more commonly merely changes them.

GENERAL FEATURES OF INFLAMMATION INCLUDE

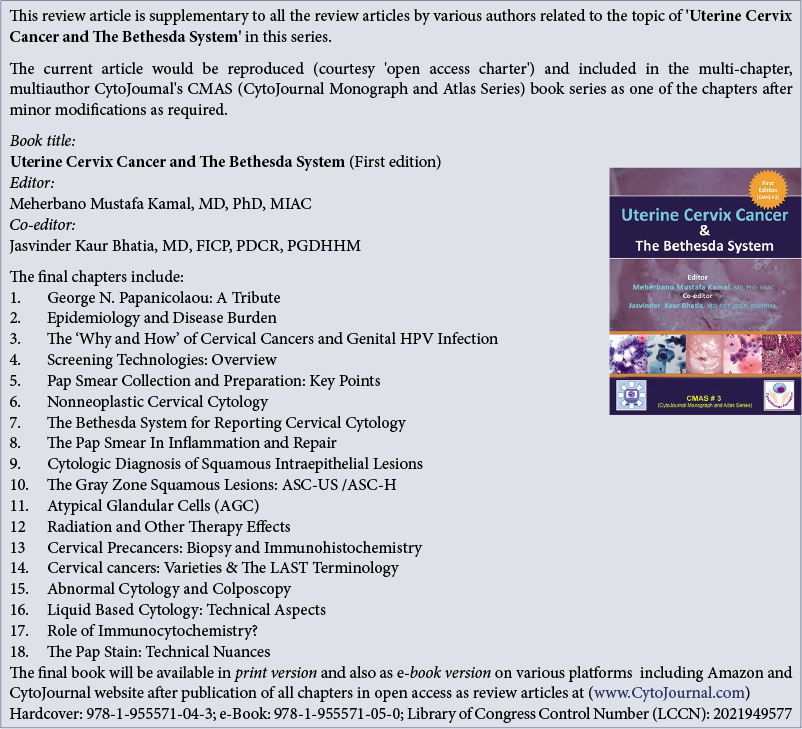

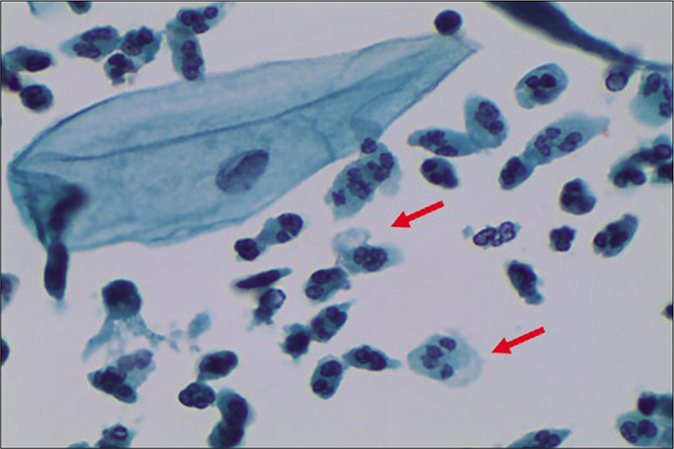

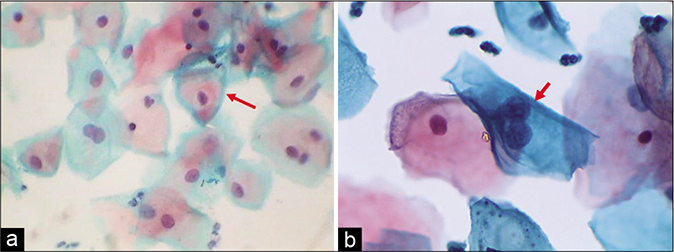

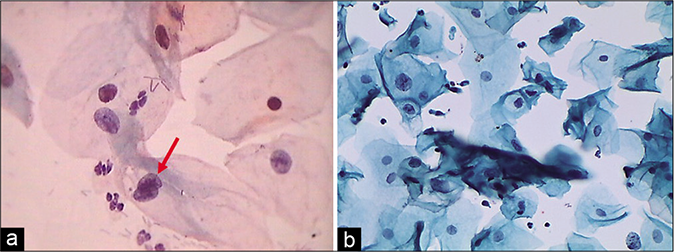

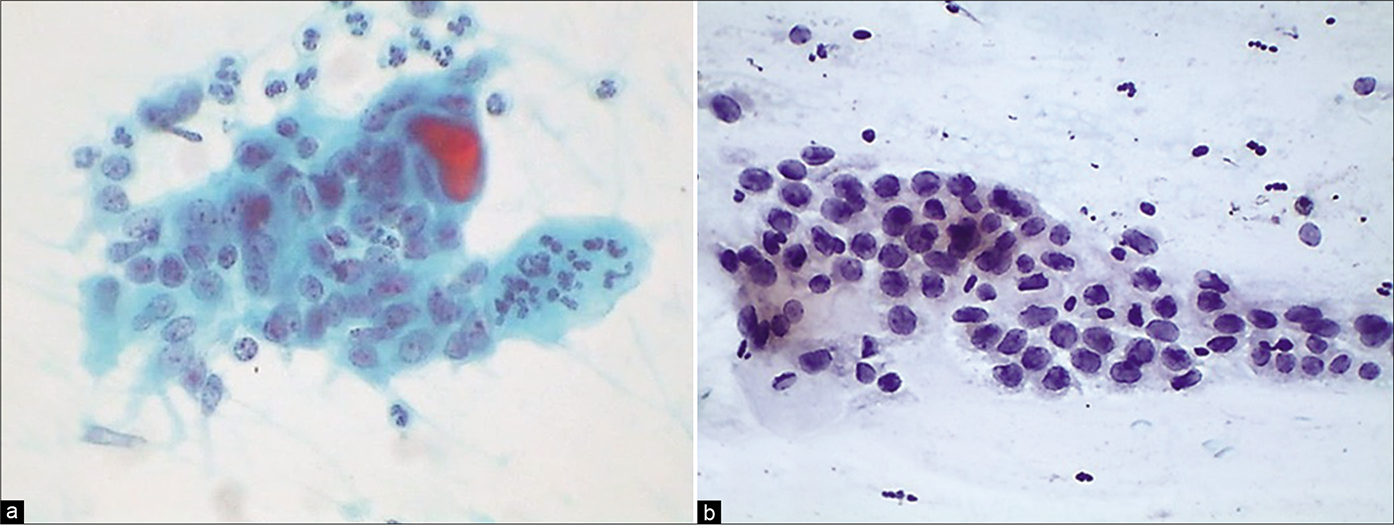

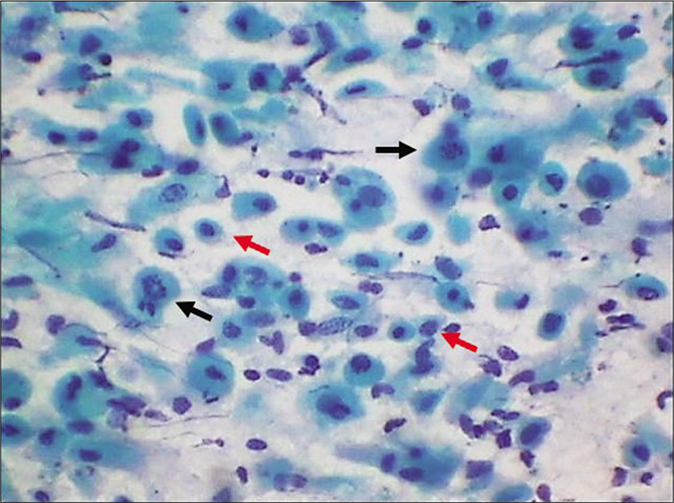

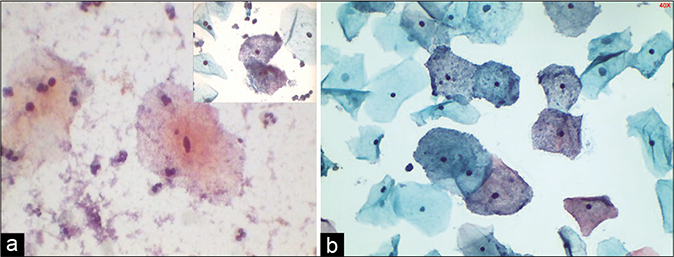

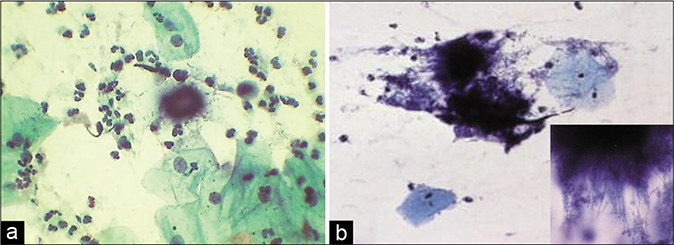

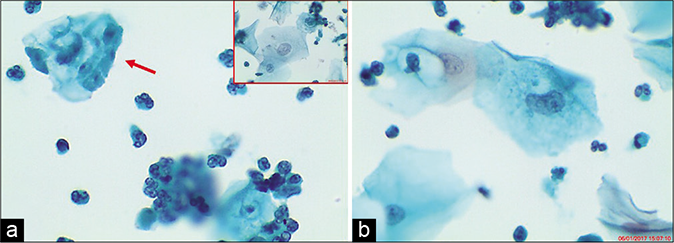

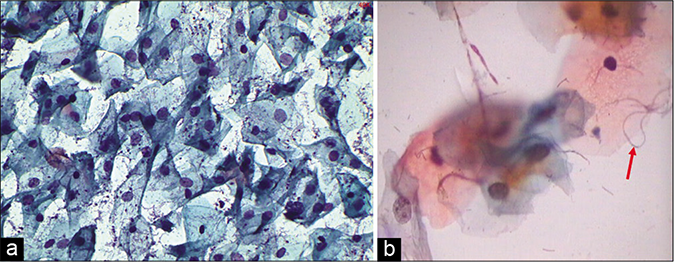

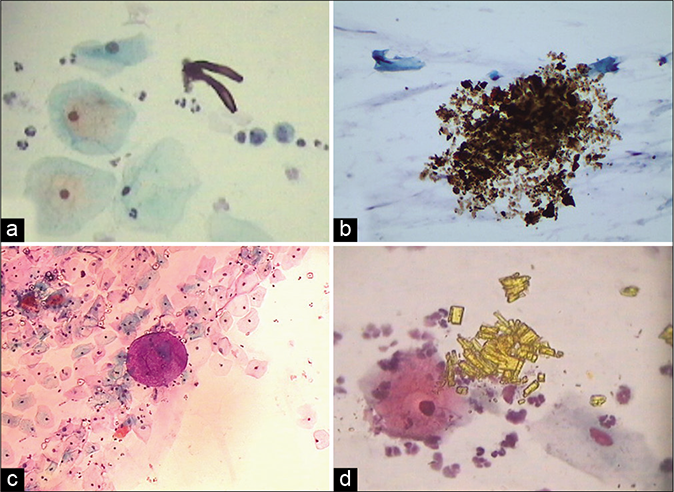

A marked increase in acute and chronic inflammatory cells beyond the physiological mild-to-moderate leukocytosis seen in normal women. The polymorphs seen in inflammatory conditions show degenerative features in the form of vacuolation and disintegration of their cytoplasm, karyorrhexis, and karyolysis, as a result of which plenty bare nuclear lobes are seen throughout the background of the smear [Figure 1]. Whereas the physiological leukocytes appear healthy and are seen in a streaming pattern being spread along with the mucus and not overlapping or obscuring the squamous cells as in an inflammatory smear [Figure 2]

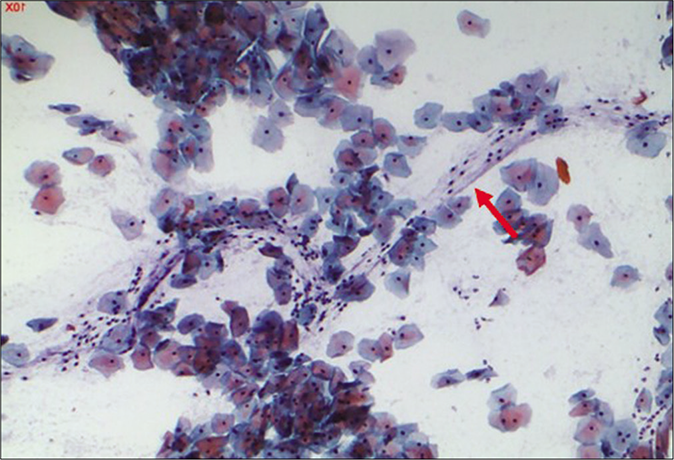

The background of the smear may be fibrinous, granular, or proteinaceous. A variety of microbes including diplococci, staphylococci, and streptococci (singly or in colonies) may be seen in the background [Figure 3]

- LBC preparation. Leukocytes showing degenerative features in the form of cytoplasmic vacuolation (red arrow), karyorrhexis (red arrow), and karyolysis (×40).

- CP smear – leukocytes seen in a streaming pattern (red arrow) in an otherwise normal Pap smear (×40).

- CP smear – acute inflammation – smear is showing dirty background, granular cytolytic debris, and variety of microbes singly or in colonies. Inset shows bacterial colonies in higher magnification (×40).

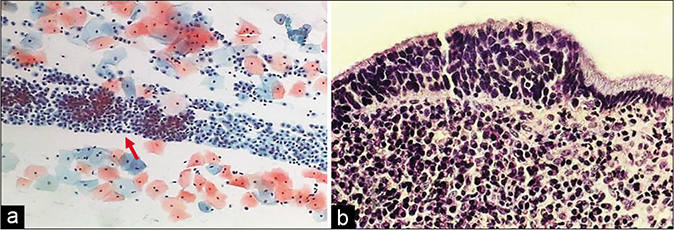

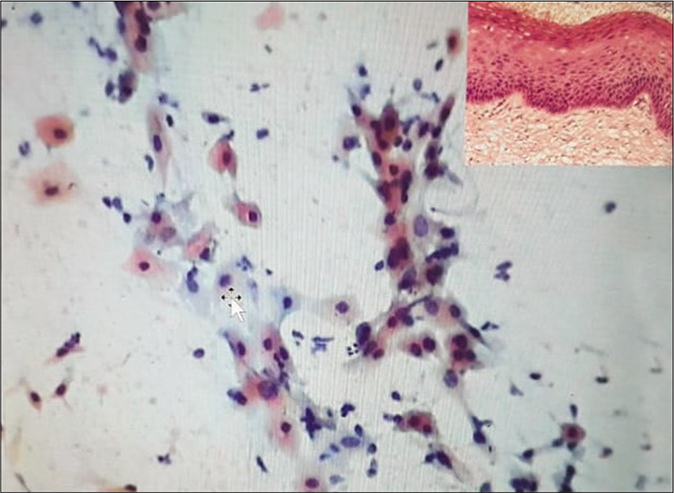

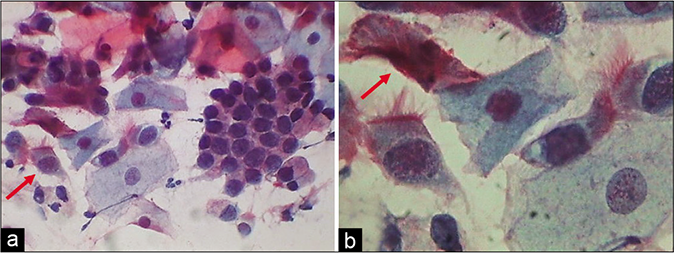

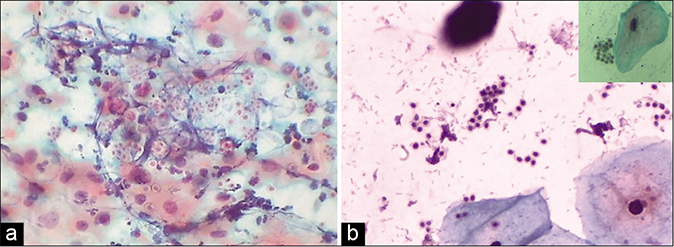

The composition of the cell population in an inflammatory smear also changes. Inflammation and repair causes damage and regeneration of the squamous epithelium and this results in more number of parabasal, basal, and sometimes reserve cells in the smear [Figure 4][5]. At times, vigorous scraping of the inflamed or dysplastic epithelium may result in microbiopsies in the Pap smear microbiopsies [Figure 5]. On the other hand in some circumstances, inflammatory irritation may cause non-hormonal maturation to superficial squamous cells that are resistant to lactobacteria-induced cytolysis.

- (a) A sheet of reserve cells in an inflammatory smear (red arrow). These are small round or triangular in shape with a central nucleus. (b) Histopathology showing a single layer of cuboidal to columnar endocervical cells beneath which is seen the hyperplasia of reserve cells and below which is a dense zone of chronic inflammatory cells (×40).

- (a) CP smear – microbiopsies of inflamed epithelium represented in cervical smear as a result of vigorous scraping. Acute inflammatory cells infiltrating the epithelium are seen ×4. (b) CP smear – microbiopsies of inflamed epithelium represented in cervical smear as a result of vigorous scraping. Acute inflammatory cells infiltrating the epithelium are seen ×10.

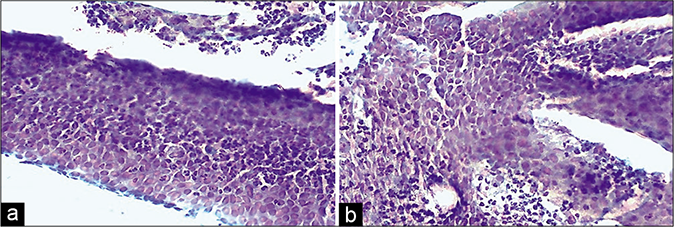

Histiocytes and giant cells with engulfed polymorphs and nuclear and cytoplasmic debris are generally seen if carefully observed [Figures 6 and 7].[3]

- CP smear – histiocytes with foamy cytoplasm (red arrow) with inset showing a giant cell with engulfed leukocytes (×40).

- (a) CP smear – sheets of histiocytes may be mistaken for parabasal or glandular cells. The latter are present in honeycomb pattern or picket fence arrangement. Note the foamy cytoplasm and engulfed debris (red arrow) (×40). (b) Colposcopy showing hypertrophic edematous and congested glandular epithelium in acute cervicitis. Islands of immature and mature metaplasia are seen as faint acetowhite areas within the transformation zone..

INFLAMMATORY CHANGES IN SQUAMOUS EPITHELIAL CELLS

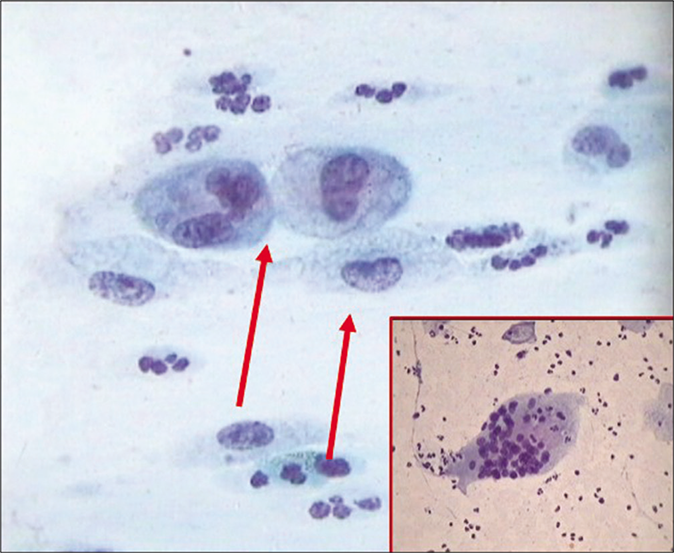

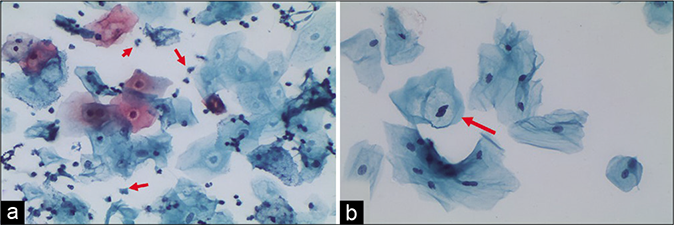

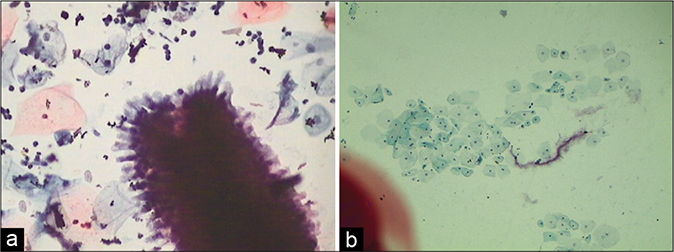

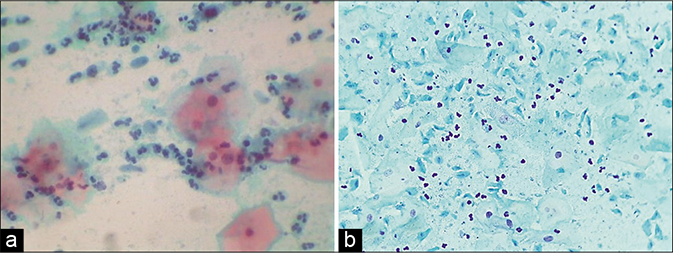

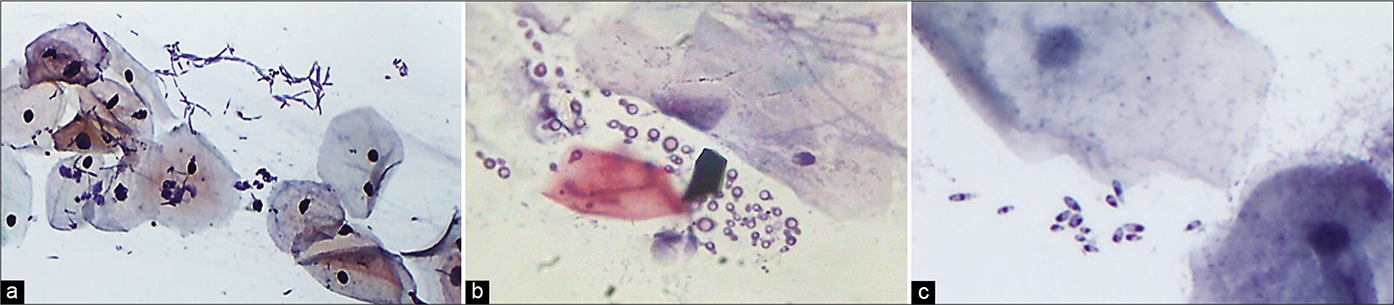

Cytoplasmic reactions to inflammation include degenerative and/or reactive changes. Pale staining of the cytoplasm or narrow zones of clearing around the nucleus – the inflammatory perinuclear halo which is particularly seen in Trichomonas infestation, also known as the “trich halos” (they can trick the unwary by mimicking the koilocytes). As a rule, the width of an inflammatory halo (i.e., the space between the nucleus and cytoplasm) is less than the diameter of an intermediate cell nucleus and the outline or the boundary of this halo is often vague or poorly defined [Figure 8]. These are also known as the pseudokoilocytes. The halos of koilocytes are much larger, more sharply defined and their nuclei are big and dark. Polymorphs are seen many times permeating the cytoplasmic vacuolation [Figure 9].[6]

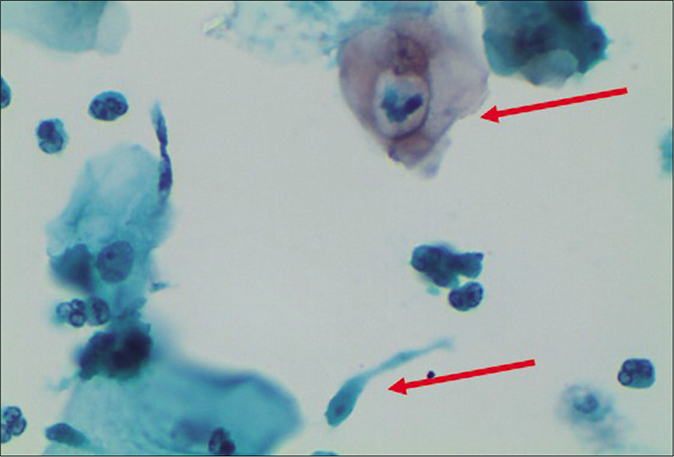

Vacuolar cytoplasmic degeneration is a common inflammatory change. Vacuolar degeneration of cytoplasm, pale degenerating swollen nuclei with indistinct chromatin and loss of the sharp details of the nuclear envelope are additional features [Figure 10]. The cells appear frayed, ragged, or moth-eaten eventually leading to cytolysis. Vacuolar degeneration is particularly common in metaplastic cells. Moreover, when this is associated with nuclear atypia, it can be mistaken for a koilocyte. However, these cells appear smaller than a koilocyte and the classical nuclear features of the latter are also missing [Figure 11]. Squamous cells with a large single vacuole pushing the nucleus to the periphery, giving a soap bubble appearance, are also seen in the Pap smear collected from the IUCD wearers.[6] The combination of vacuolated cytoplasm and atypical nuclei may also suggest adenocarcinoma

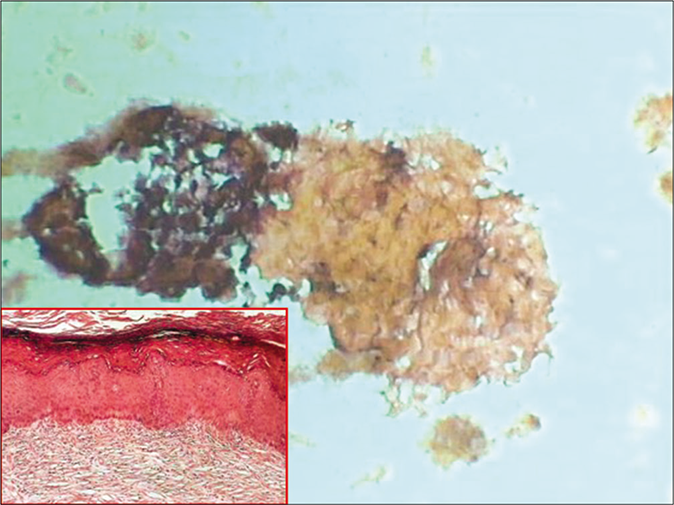

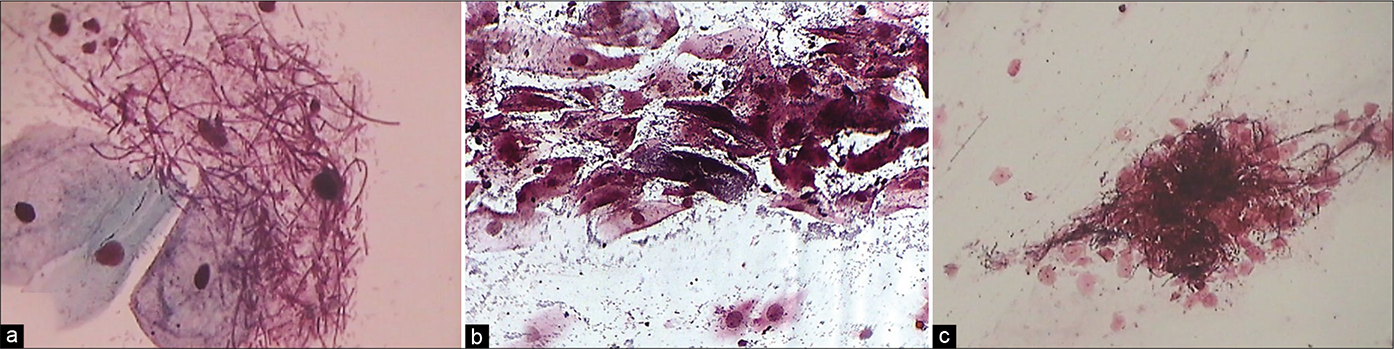

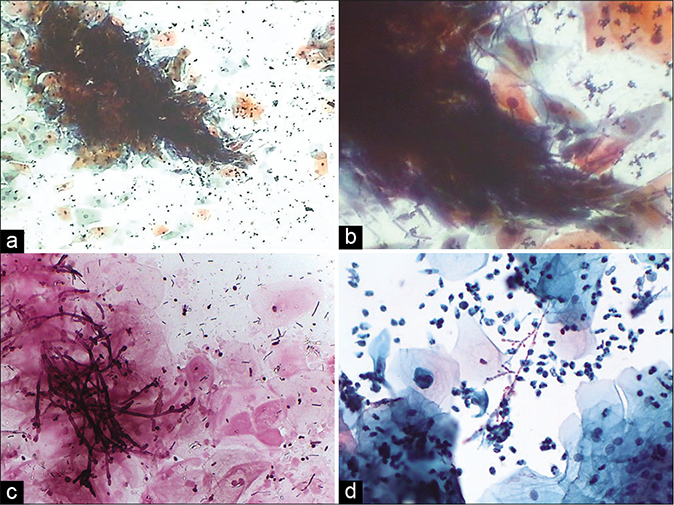

Reactive changes include parakeratosis, dyskeratosis, and hyperkeratosis. Parakeratotic cells are miniature keratinized squamous cells with pyknotic nuclei and dense eosinophilic cytoplasm resulting from surface keratinization (generally seen in psoriasis). This abnormality of the cervix epithelium was named pseudoparakeratosis [Figure 12].[7] Dyskeratosis involves premature or excessive keratinization of individual squamous cells that are spread sparsely throughout the smear. The cytoplasm of these cells is dense orangeophilic. The N/C ratio is normal and nuclear outlines are smooth. Hyperkeratosis is associated with nucleated squamous cells (squames), of characteristic pale yellow color in Papanicolaou stain, and are shed from the surface of the keratinized squamous epithelium [Figure 13]. The presence of dyskeratotic, atypical parakeratotic cells and anucleated squamous cells should be mentioned in the report because of the remote possibility that these cells may have originated from the surface of a warty lesion (HPV associated) or squamous cancer masquerading as leukoplakia [Figure 14]. Such patients deserve a closer clinical look and HPV DNA test for high-risk viruses followed by colposcopy if necessary. In squamous carcinomas with the features of leukoplakia, anucleated squamous cells are usually accompanied by cells with abnormal, hyperchromatic nuclei that allow an accurate diagnosis.

Staining alterations: Intermediate, parabasal, and metaplastic cells sometimes become eosinophilic or orangeophilic, staining dense pink to orange instead of green. This is commonly seen in senile vaginitis or atrophic smears. Pseudokeratinized cytoplasm with atypical nuclei may mimic low-grade keratinizing dysplasia. Polychromasia or two-tone staining of the cytoplasm – pink and blue or green – may occur or cytoplasm may stain less intensely as a result of inflammation [Figure 15].

- (a) “Trich halos” plenty TV are seen in the smear (red arrow). (b) Non-specific inflammatory perinuclear clearing and binucleation can mimic koilocytes (red arrow). However, there is no nuclear atypia (×40).

- LBC smear – engulfed leukocyte in a cytoplasmic vacuole (upper arrow). Trichomonas vaginalis is seen in the lower half (lower arrow) of the field (×40).

- (a) LBC smear showing vacuolar degeneration of cytoplasm with pale degenerating swollen nuclei with indistinct chromatin and loss of the sharp details of the nuclear envelope. (b) Same features seen in CP smear (×40).

- (a) CP smear – Pseudokoilocytes – metaplastic cells showing cytoplasmic vacuolation, however, nuclear atypia is lacking – CP smear. (b) LBC smear – Pseudokoilocyte – metaplastic cells showing cytoplasmic vacuolation, however, nuclear atypia is lacking. Smear is showing pseudokoilocyte along with Candida infection (×40).

- CP smear – parakeratosis – these are small superficial squamous cells with sharply outlined cytoplasmic margins and small pyknotic nuclei. Inset showing histopathology of the same (×40).

- CP smear – keratinized plaque of orange keratotic material from a hyperkeratotic squamous epithelium. Cell borders are indistinct. Inset showing histopathology of the same (×40).

- CP smear – dyskeratosis and atypical parakeratosis: Small round to oval polygonal to spindle cells with dense eosinophilic cytoplasm and pyknotic hyperchromatic and mildly pleomorphic nuclei. These may camouflage a more serious lesion. Compare with cells of Figure 12 that are appearing as a benign reaction to inflammation (×40).

- (a) Polychromasia or two-tone cytoplasm (red arrow) are seen in squamous cells of an inflammatory smear. Benign binucleation is seen at the arrows. (b) Binucleation and bland nucleomegaly in an inflammatory smear (×40).

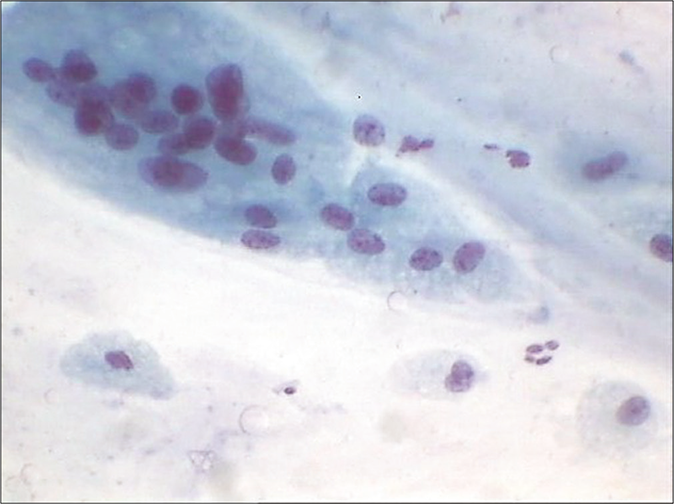

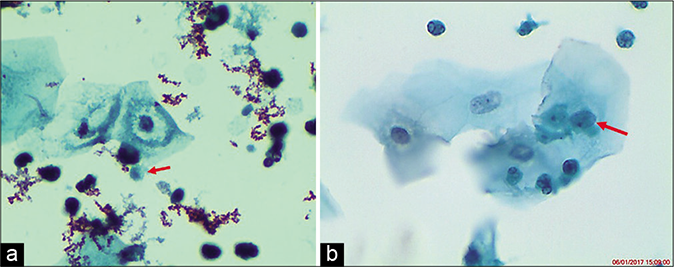

Nuclear changes: Nuclear features are a key to distinguishing reactive and degenerative changes from dysplasia. The nucleus in inflammatory smears is big but not dark as is seen in dysplasia where it is both – big and dark. More frequently observed is the bland enlarged nucleus with pale staining chromatin due to fluid absorption. Chromatin may be indistinct and smudgy rather than crisp and distinct [Figure 10]. These changes vary from cell to cell resulting in the prominence of anisonucleosis. By and large, the nuclear size remains <2 times the size of an intermediate cell nucleus. Wrinkling of the nuclear membrane and central clearing with selective condensation of the chromatin at the periphery are other degenerative changes. This may be associated with common degenerative changes associated with inflammation such as karyopyknosis, karyorrhexis, and karyolysis. Hyperchromasia, binucleation, and the presence of nucleoli favor a reactive process. However, the contours of the nucleus are smooth and round and this change is uniformly seen in most cells [Figure 16]. As a general rule, the differences between inflammatory change and dysplasia are a matter of degree.

- (a) CP smear – minimal hyperchromasia (red arrow), binucleation, anisonucleosis, and nuclear enlargement and smooth nuclear contours favor reactive cellular changes associated with inflammation (×40). (b) LBC smear – minimal hyperchromasia, binucleation, anisonucleosis, and nuclear enlargement and smooth nuclear contours favor reactive cellular changes associated with inflammation (×40).

Features favoring reactive/inflammatory changes include slight nuclear enlargement (<×2 an intermediate cell nucleus), smooth nuclear membranes, fine pale chromatin, conspicuous nucleoli may be present, inflammatory perinuclear halos (differential koilocyte halos), cytoplasmic fraying, vacuolation, polychromasia, and pseudokeratinization. The background is not clean and may be “dirty” with granular and fibrinous debris that tends to cling to epithelial cells in LBP.[6]

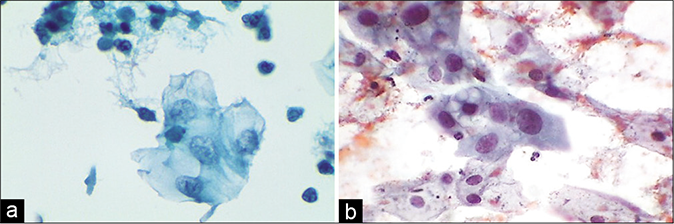

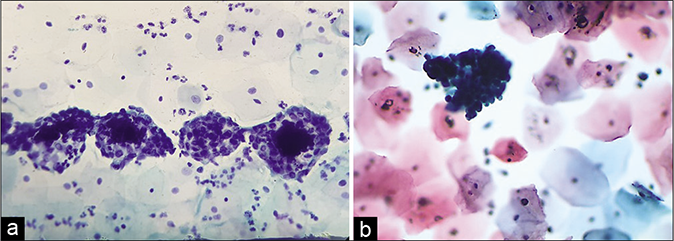

INFLAMMATORY CHANGES IN ENDOCERVICAL CELLS

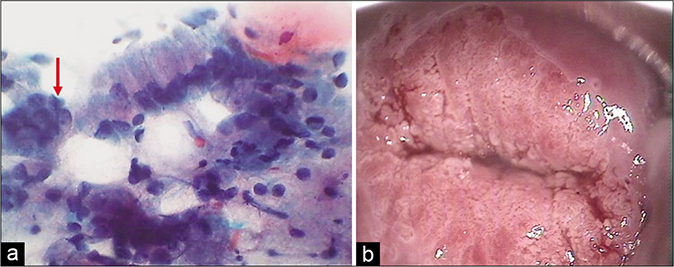

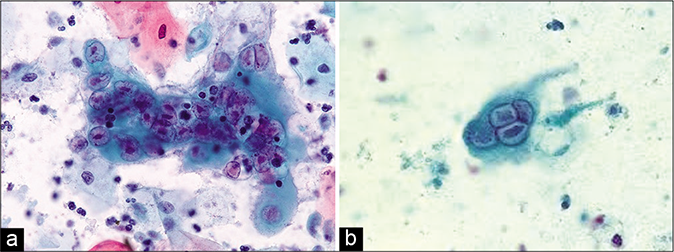

Acute endocervicitis may produce a striking degeneration of the cytoplasm in the form of cytoplasmic vacuolation (goblet cell change) or tattering and fraying of cytoplasm [Figure 17]. In the latter case, plenty bare nuclei stripped of cytoplasm are often observed throughout the smear singly or in clusters. Conspicuous cytoplasmic vacuoles, sometimes infiltrated by polymorphonuclear leukocytes, may be observed. Nuclear overlapping (pseudomultinucleation) is frequently observed creating suspicion of various viral infections [Figure 18]

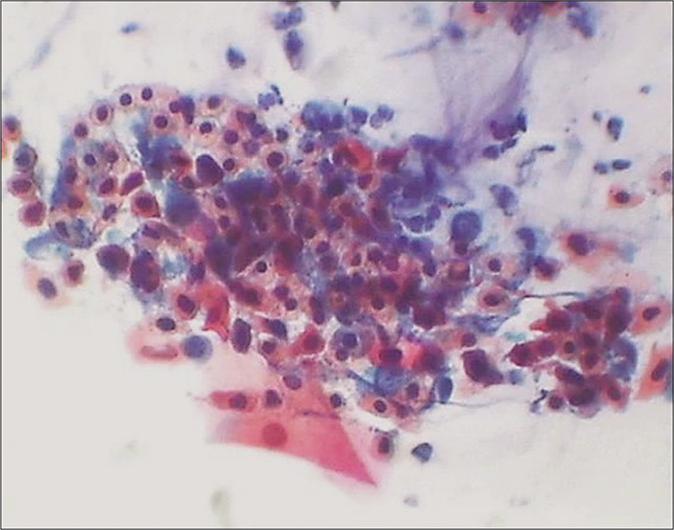

Endocervical cells show significant nuclear enlargement but the shape remains round to oval. Hyperchromasia and chromatin may be somewhat coarsened raising the suspicion of AGUS (atypical glandular cells of unknown significance) [Figure 19]. Maintenance of honeycomb pattern, flat sheets, picket fence arrangement without nuclear crowding, and smooth round nuclei are clues to a benign process

The most conspicuous reactive nuclear changes consist of the presence of numerous chromocenters and one or more quite large and conspicuous nucleoli [Figure 20]. Ciliocytophthoria is a phenomenon where in tufts of cilia (pink to red) along with the terminal plate are stripped off the cytoplasm and are seen lying loose amongst the cells [Figure 21]

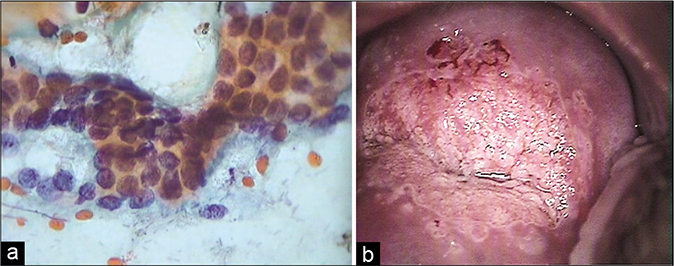

Polypoidal endocervicitis is often referred to small clusters, papillae, or balls of endocervical cells with smooth outlines and without a fibrovascular core [Figure 22]. The periphery of these clusters may show columnar cells and may have pale intermediate zones and dark inner cores [Figure 23]. When seen, the nuclei at the periphery show reactive features associated with inflammation. These are not true endocervical polyps instead represent tips of hyperplastic endocervical mucosa that is described as finger-like processes or “sea anemone” like structures during colposcopy.[7]

Chronic Inflammation: Chronic inflammatory processes of a minor degree are exceedingly common in the female genital tract and produce few, if any, specific morphologic changes in epithelial cells. The smears may show evidence of benign abnormalities such as squamous metaplasia and repair, although their relationship to inflammatory processes is not always evident. The only constant evidence of chronic inflammation is the presence of lymphocytes, occasional plasma cells, and macrophages. The latter is oval or bean shaped and has a prominent nuclear membrane that stands out readily against the delicate bluish cytoplasm [Figure 6]. Occasionally, it is difficult to differentiate small macrophages from parabasal cells originating from squamous metaplasia of the endocervix. Rarely, mitotic figures may be observed in macrophages in smears.[7] Nasiell (1961) pointed out that the mononucleated macrophages may be mistaken for cancer cells and that the differential diagnosis is based on evidence of phagocytic activity.[8] Multinucleated macrophages are frequently observed in smears of postmenopausal women and may achieve very large sizes, even in the absence of inflammation [Figure 24].

- (a) CP smear – tall columnar endocervical cells with large body of finely vacuolated cytoplasm, slight nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, and plenty bare nuclei. Pseudomultinucleation is seen at arrow (×40). (b) Colposcopic appearance of infected ectopy. Glandular villi showing hyperplasia, and early changes of metaplasia in the form of tranluscent villi.

- (a) Plenty bare endocervical nuclei. (b) Pseudomultinucleation is seen at arrow.

- (a) Reactive nuclear atypia in glandular cells. (b) Colposcopy showing fusion of villi resulting in islands of metaplasia of variable density within the TZ and surrounding the gland openings. Such hypertrophic acetowhite metaplastic epithelium is partly responsible for equivocal cytology findings. Multiple biopsies showed acanthotic and dyskeratotic squamous epithelium only.

- (a) CP smear – sheet of endocervical cells infiltrated by leukocytes. There is loss of the regular honeycomb pattern with ragged cytoplasmic borders. Numerous chromocenters and nucleoli seen. (b) Reactive nuclear features in the form of nuclear enlargement, anisonucleosis, and mild hyperchromasia are seen (×40).

- (a) Honeycomb sheet of endocervical cells and ciliated columnar cells (red arrow) (×40). (b) Ciliated columnar cells with the terminal plate and cilia. Arrow shows ciliocytophthoria (×100).

- (a) CP smear (×10) – clusters, papillae, and balls of endocervical cells with smooth outlines and without a fibrovascular core generally represent exfoliated tips of friable hyperplastic endocervical mucosa (b) seen as “sea anemone” like appearance on colposcopy. Histopathology of the same (c).

- (a) A cluster of endocervical cells with radiating cytoplasm of columnar endocervical cells. (b) Inspissated mucinous material taking a configuration of Curschmann’s spiral (×40).

- CP smear – a case of atrophy: Multinucleation resembling giant cells can be either true histiocytic or an aggregate of nuclei in a common cytoplasmic background as seen in atrophy and postpartum specimens. They are different from syncytiotrophoblasts and multinucleated cells found in herpes infection (×10).

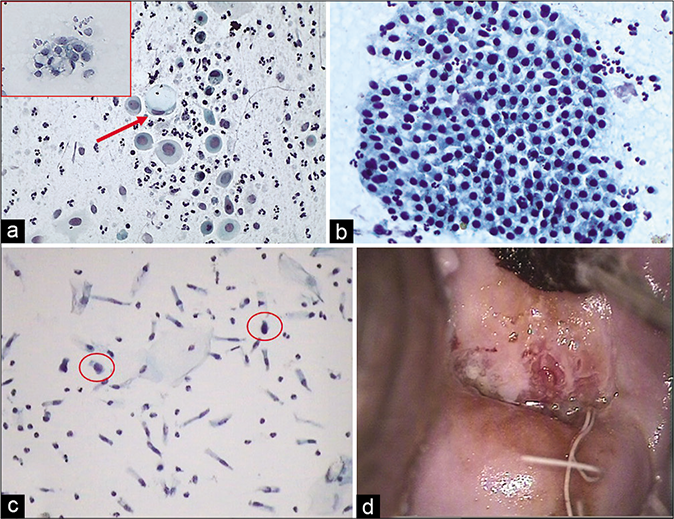

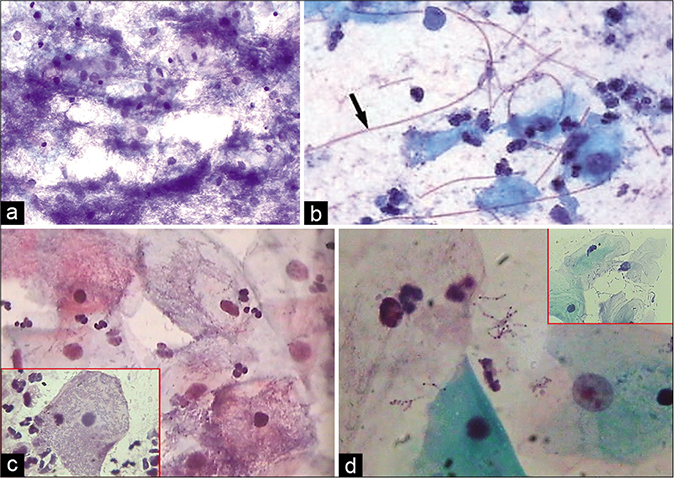

IUCD-ASSOCIATED CELLULAR CHANGES

The chronic irritation of the intrauterine device (IUD) thread and the device itself can lead to exfoliation of glandular cells from the endocervix and the endometrium. These may show cellular alterations (atypia) that can be seen in both squamous and glandular cells. When these changes are seen in LBPs with less number of inflammatory cells, the interpretation can be difficult. There is no definitive evidence for the association of dysplasia in long-term IUD wearers.[5] The common findings as observed in the cervical smears include:

Shedding of endometrial cells at any stage of the cycle [Figure 25a and 25b]

The “IUD cells” that are single endometrial cells with a high N/C ratio may resemble cells from a HSIL [Figure 26c]

Single (bubble gum cell) or clusters of enlarged vacuolated glandular cells [Figure 26a]

Acute inflammatory exudate and histiocytes with engulfed sperms

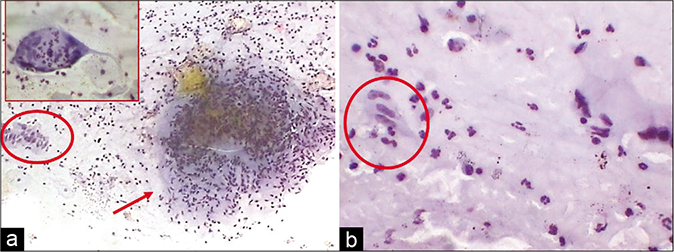

Actinomycotic colonies particularly with plastic devices [Figure 27][3]

Columnar cell hyperplasia may mimic papillary tumors arising either from the cervix, uterus, or the ovaries [Figure 26b]

Psammoma bodies when seen in association with atypical glandular cells may be mistaken for a metastatic lesion particularly of ovarian neoplasm.[6]

- (a) IUD-related changes – clusters of endometrial cells in any stage of the cycle – CP smear. (b) Same in – LBC smear.

- (a) Single (red arrow) or clusters (inset) of enlarged vacuolated glandular cells. (b) CP smear – end on hyperplastic benign sheet of columnar cells. (c) LBC – occasional atypical glandular cell (circle) (×40). (d) IUCD thread at the external os with colposcopic feature of chronic cervicitis.

- (a) CP smear – simple repair showing a flat sheet of immature metaplastic cells with bland nuclear enlargement, finely granular evenly distributed nuclear chromatin, and small single nucleolus. Note inflammatory cells within the sheet (×40). (b) LBC smear showing cytoplasmic projections that give a spidery contour to the metaplastic cells also called as “cookie cutter” appearance.

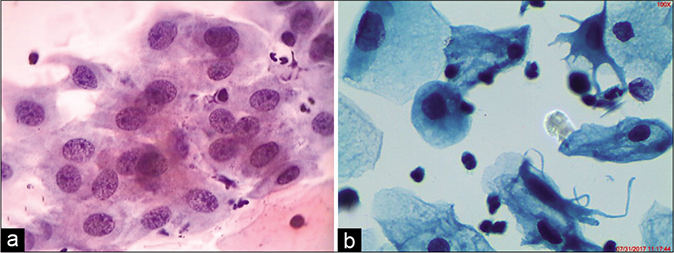

REPAIR (FLORID SQUAMOUS METAPLASIA)

Inflammation and repair are a hand-in-hand phenomenon. The term repair has been introduced into the field of gynecologic cytology by Bibbo et al. (1971)[9] and Patten (1978).[10] “Repair” reaction may occur after surgical procedures or as a reaction to chronic inflammatory events or in the presence of a foreign body or object in the endocervical canal, for example, intrauterine contraceptive devices or endocervical polyps may be the cause of such abnormalities. There remain, however, a number of patients in whom similar cell abnormalities may be observed in smears in the absence of any known events that could account for the “repair.” Basically, the small round or triangular reserve cells present beneath the glandular lining epithelium have the potential to differentiate toward both the squamous and the glandular epithelium. During the complex phenomenon of repair, the delicate endocervical glandular lining is replaced by the tougher squamous epithelium. In the histologic material, this process of repair appears as tongues of poorly formed squamoid or immature or metaplastic epithelium that is composed of young epithelial cells bridging the defect caused by prior surgery. The immature cells do not exfoliate spontaneously but can be lifted from the surface of the cervix by the abrading action of the spatula or the cytobrush.

CYTOLOGY

In the Pap smear, these young immature squamous cells are generally referred to as metaplastic cells. The cells are the size of parabasal or early intermediate cells seen in flat sheets, composed of tightly fitting cells. These cells are not a normal constituent of the smears once the transformation zone has developed.

Detached cells show cytoplasmic projections (spidery contour to the cells) or bridges loosely connecting adjacent cells [Figure 28]. The cells may vary in size and their cytoplasm may be vacuolated and infiltrated with polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The cytoplasm of these cells is delicate or dense cyanophilic or prematurely keratinized. Intracytoplasmic vacuolation, at times with engulfed polymorphs, may be seen. The N/C ratio is slightly high. The nuclei vary in size and the chromatin may be vesicular or coarse granular [Figure 29]. With progressive maturation, the cells increasingly resemble intermediate and superficial cells and cannot be distinguished from mature cells of a normal cervical epithelium. The histologic evidence of true repair or a metaplastic origin of a mature squamous epithelium is the presence of underlying, either of the opening of endocervical glandular crypts (may lead to form Nabothian cysts later) or a zone of endocervical glands and stroma indicating its endocervical source.

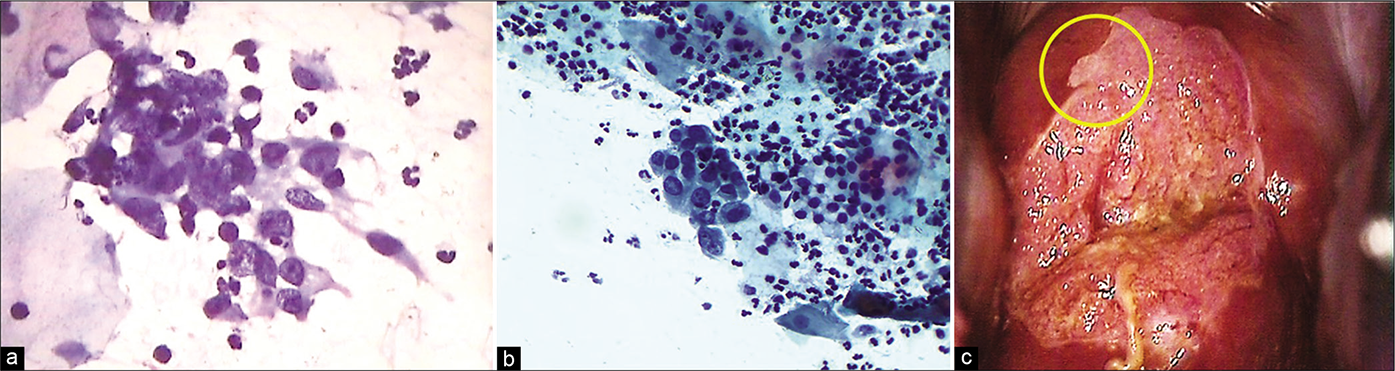

- (a) Aggregate of immature metaplastic cells showing variable preservation and vacuolation of cytoplasm and nuclear hyperchromasia (×40). (b) Aggregate of immature metaplastic cells showing dense cytoplasm and nuclear hyperchromasia (×40). Inset showing histology of the same. (c) Colposcopy showing dense cuff of abnormally thick metaplastic tissue surrounding the gland openings raising the suspicion of CIN. Biopsy showed immature squamous metaplasia with atypia.

- (a and b) CP smear – Crowding and overlapping of cells in a sheet of immature metaplastic cells. Anisonucleosis with coarse somewhat hyperchromatic nuclear chromatin is seen. These features are beyond typical repair (×40). (c) Colposcopically suspicious lesion abutting SCJ (yellow circle). Biopsy showed features of atypical metaplastic epithelium only.

ATYPICAL SQUAMOUS METAPLASIA/ ATYPICAL REPAIR

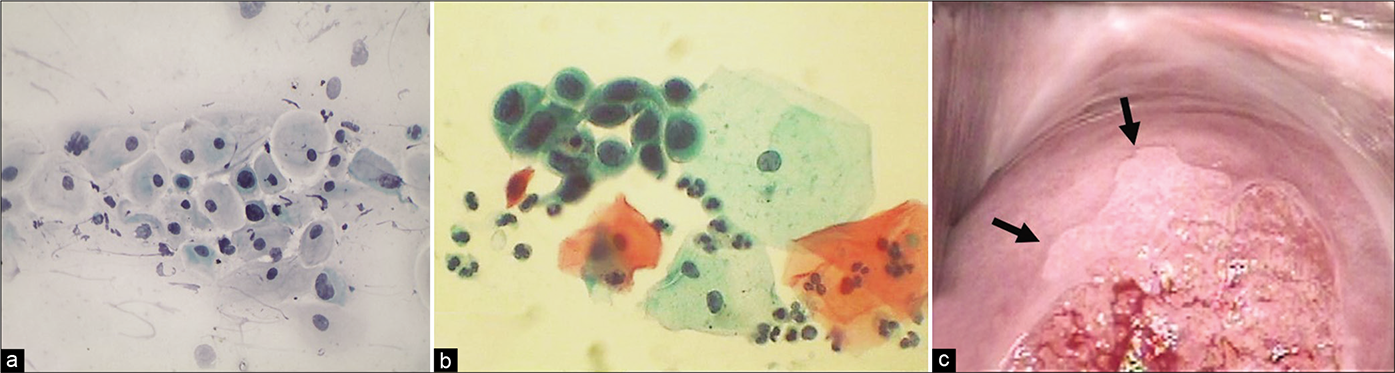

Atypical repair is characterized by reparative cells that have cytologic abnormalities that exceed those of typical repair. Atypical repair is a form of atypical squamous or glandular cells associated with a wide variety of conditions ranging from reactive to neoplastic. Because the precise identification of such cells is difficult, their classification as “metaplastic” or “endocervical” may depend on the preference of the observer. No doubt some of these abnormalities could be classified as atypical squamous or endocervical cells of unknown significance (ASCUS or AGUS). The term “atypical repair” is not included in the Bethesda System lexicon. However, when such changes are seen, they can be described using TBS terminology of “atypical squamous cells” or “Atypical glandular cells.” Occasionally, the component cells of squamous metaplasia in tissue and smears show slight to severe abnormalities. The slight changes are cell and nuclear enlargement or binucleation confined to a few cells within the cluster [Figure 30]. The biopsies in such cases disclose minimally atypical metaplasia. More severe changes include tissue fragments of immature squamous and glandular cells in tissue fragments with crowding and piling up of cells.

- (a and b) Atypical metaplastic cells – the nuclear atypia may be interpreted as ASC-H (×40). (c) Colposcopic appearance of cervix showing a sharp acetowhite area (arrows) abutting SCJ creating a suspicion of CIN. Biopsy did not reveal any CIN lesion.

Significant cellular and nuclear enlargement, variability in nuclear size, coarse granulation of chromatin, and the presence of prominent nucleoli go beyond those of typical repair. Single cells with similar features are uncommon. The background of the smear usually shows a great deal of fresh blood and inflammation. Mitosis may be seen. Presence of acute inflammatory cells is often seen within these cell clusters and this is a soft clue pointing toward repair rather than a SIL. Patients with marked nuclear changes should have the benefit of a close, careful follow-up, including colposcopy and biopsies of cervix, particularly if, in addition to cell clusters, single abnormal cells are present in the smear [Figure 31]. On further investigation, many such patients are subsequently shown to harbor precancerous lesions or even cancer of either squamous or endocervical type. Therefore, the role of testing for human papillomavirus in such cases holds special significance.[11] The risk of SIL in women with atypical repair is generally within the range reported for ordinary ASC-US (i.e. around 25% SIL and around 10% HSIL).[12] Rimm et al., 1996, observed that 25% of patients with “atypical repair” pattern in smears harbored squamous intraepithelial lesions (SILs) of low or high grade. Colgan et al. (2001) reported that in a major survey of laboratories in the United States, repair was the most common source of false-positive and false-negative smears. In the absence of supporting clinical or histologic evidence, the concept of repair, although occasionally correct, is a dangerous one as it may mislead even an experienced observer. Cell abnormalities of considerable magnitude not based on secure clinical and histologic data must be investigated further, regardless of label.[13]

- (a and b) Atrophy with inflammation. Granular debris is seen in the background along with degenerating parabasal cells, bare nuclei of the parabasal cells, and pseudo-parakeratotic cells. The latter are degenerated orangeophilic or eosinophilic parabasal cells with nuclear pyknosis – CP smear. (b is LBC smear) ×40 – LBC smear ×40.

POINTS TO REMEMBER

Inflammatory smears are a poor predictor of cervical infection. The rate of positive cultures in women with or without cytological inflammatory changes is 48 and 47%, respectively. Therefore, clinical considerations are mandatory before treatment

-

Those experienced in cytology will be aware that there are some inflammatory and degenerative characteristics shared with dysplastic cells. However, when caught in the uncertainty about the significance of an inflammatory picture, there is a risk of under/ over reporting of epithelial abnormality. The cytologist must report such findings in the light of clinical details because the policies on the management of smears with inflammatory changes and possible dyskaryosis vary widely, but should be based on the following principles.

In a routine gynecologic practice, a repeat smear after adequate antimicrobial treatment or at an interval of 3–6 months often helps to resolve the dilemma

Microbiological investigations followed by referral for colposcopy is indicated if the findings persist

If the woman is asymptomatic and the cervix appears normal, minor inflammatory changes which are clearly not dysplastic and which show no evidence of a specific pathogen can be reported as within normal limits (WNLs)

Documentation of reactive cellular changes is important in the first place to facilitate clinical-cytologic correlation and second, studies have reported a slight increase in the incidence of SIL in cases interpretated as reactive compared to those interpretated as WNLs.[14]

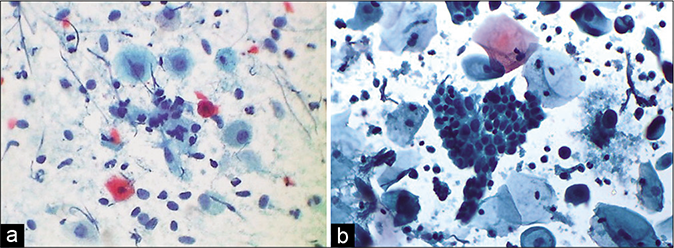

ATROPHIC CERVICITIS/VAGINITIS

Senile or atrophic vaginitis or cervicitis implies inflammation of the atrophic epithelium associated with deprivation of hormones required for its maturation and occurs most commonly in peri- and post-menopausal women. In an acute inflammation, predominantly two effects are seen:

The first is an increased maturation of the squamous epithelium with reappearance of intermediate and even superficial squamous cells. The reason for this phenomenon is in all probabilities an increased blood supply to the squamous epithelium. In the presence of inflammation, one should not attempt to estimate the level of estrogenic activity in smears

The second effect of acute inflammation may be an increase in cell necrosis and, hence, cell debris which, combined with the phenomena of naturally occurring cell damage in advanced atrophy, may make the interpretation of such smears particularly difficult [Figure 32]. The presence of a marked inflammatory exudate and cell necrosis may also occur in advanced cancers of the cervix and the endometrium. Therefore, careful screening of such smears is mandatory.[7]

- LBC smear – dissociated parabasal cells showing karyorrhexis (black arrows) of nuclei interspersed with plenty smaller basal cells (red arrows) (×40).

The smear pattern of an atrophic smear with marked inflammation comprises sheets of and dissociated parabasal cells. Loss of fragile cytoplasm of the thin atrophic and relatively dry epithelium leads to plenty bare nuclei throughout the smear. The cytoplasm of these cells is poorly stained with dense pyknotic or fragmented nuclei. These nuclei may appear as dark purple nuclear streaks due to spreading and “blue blobs” may be noted. “Red atrophy” refers to a staining reaction of the cytoplasm of the majority of cells in the smear from green to deep orange. The nuclei of such cells may be pyknotic making it difficult to differentiate such cells from malignant squamous cells.

Distinguishing squamous metaplasia from atrophy is another common dilemma. Both are comprised of parabasal sized cells.

Metaplastic cells are more robust whereas the cells of atrophy are delicate

The cytoplasm of the metaplastic cells is more dense and has a rim of dense ectoplasm and is generally arranged in a cobblestone pattern

Mucin vacuoles can occur in metaplastic cells but not in atrophic cells

Spidery forms are more frequent in metaplasia while syncytial like aggregates are more common in atrophy

The company the cells they keep is also helpful: Immature metaplastic cells are often surrounded by more mature intermediate squamous cells whereas cells of atrophy are often accompanied by undifferentiated basaloid cells [Figure 33]

Furthermore, the metaplastic cells are fewer in number and the atrophic cells dominate the smear pattern.[6]

- CP smear – atrophy – Smear showing granular background, enlargement of nuclei, and hyperchromasia. This is drying artifact. A repeat smear after local application of estrogen reverses the changes and avoids over interpretation of cells (×40).

At times because of the drying artifact, there is a nuclear enlargement with irregular nuclear membranes. However, the staining of the nuclei is pale and the chromatin is not crisp. There is also a tendency for cells to form syncytia. Such syncytial cell clusters with enlarged nuclei are difficult to differentiate from the cells of HSIL. A repeat Pap smear after appropriate antibiotic treatment followed by local application of estrogen creams (3 days–3 weeks) often helps to resolve the dilemma. The smear background becomes clean, more number of mature cells appear among whom the “hormonally deaf” cells of HSIL, when present, are easy to assess [Figure 34].

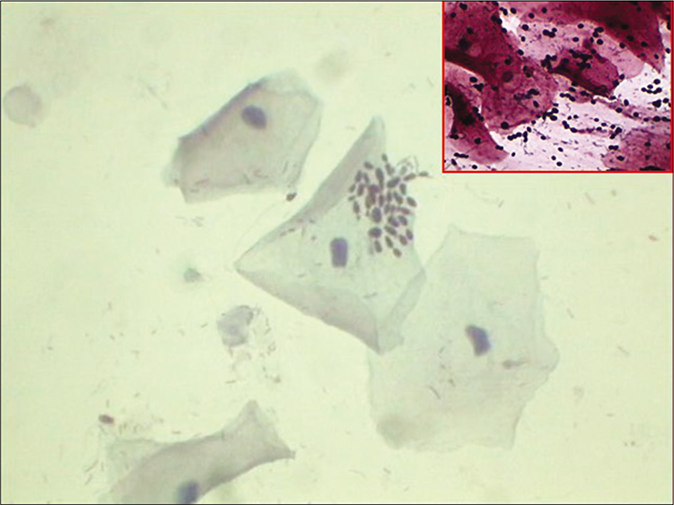

- (a) Lactobacillosis. (b) Long lactobacilli (arrow). (c) Short slender and stout (inset) Doderlein’s bacilli are seen covering complete surface of squamous cells (×40). (d) Lactobacillus species showing clubbing at one or both the ends of bacilli, resembling volutin granules of Corynebacterium diphtheriae.

ORGANISMS AND THE PAP SMEAR

| Bacteria |

| Endogenous flora of the vagina |

| • Lactobacilli |

| • Corynebacteria |

| • Leptothrix |

| Exogenous flora |

| • Gardnerella vaginalis |

| • Actinomyces organisms |

| • Coccoid overgrowth |

| • Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

| • Calymmatobacterium (Donovania) granulomatis |

| • Treponema pallidum |

| • Tuberculosis |

| Protozoa |

| • Trichomonas vaginalis |

| • Entamoeba gingivalis |

| • Entamoeba histolytica |

| Fungi |

| • Candida albicans |

| • Candida glabrata |

| Viruses |

| • HSV |

| • HPV |

| • CMV |

| • Molluscum contagiosum |

| • Adenovirus |

| • Chlamydia trachomatis |

| Special types of cervicitis and vaginitis |

| • Atrophic cervicitis |

| • Follicular cervicitis |

| • Granulomatous cervicitis |

OVERGROWTH OF ENDOGENOUS FLORA

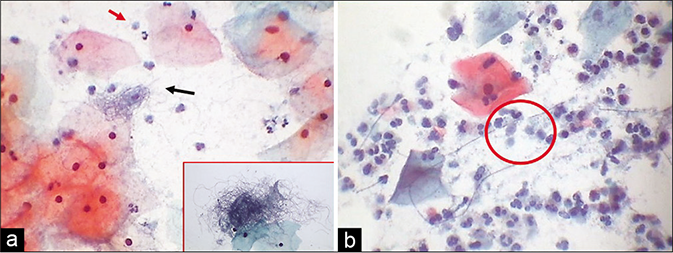

Lactobacilli play a key role in preventing diseases including bacterial vaginosis, yeast infections, STDs, urinary tract infections, and possibly even cancer.[15] The mechanisms by which lactobacilli control diseases include maintaining an acidic pH of the vagina. In specific, lactobacilli prevent pathogens from attaching to vaginal cells by blocking adhesion receptors, competing with pathogens for nutrients and producing substances like organic acids, hydrogen peroxide, bacteriocins and possibly biosurfactants that inhibit pathogens. On the other hand, some forms of lactobacilli are potentially pathogenic causing lactobacillosis. These are seen as long thick or thin filament singly or present in bunches or as small bacilli covering complete surface of squamous cells. The overgrowth of lactobacilli is not necessarily physiological.[3] Excessive lactobacteria cytolysis can cause symptoms and signs of vaginosis. Some species of lactobacilli display volutin granules (first described in Spirillum volutans) that take a metachromatic staining by Neisser stain.[16] These granules are polyphosphate (Poly-P) molecules, present at one or both the poles of bacilli or as intracellular accumulations [Figure 35]. Candida and lactobacilli have a growth synergy and often, Candida, particularly yeast forms, are seen in smears rich in lactobacilli as both these organisms prefer growing in an acidic ph.

- (a) Leptothrix also known as Leptotrichia are segmented large filamentous and may be seen like balls of hair (black arrow and inset). They are commonly associated with TV (red arrow). (b) Spaghetti and meat ball appearance (circle) (×40).

The long filamentous forms of lactobacilli need to be differentiated from Leptothrix. Leptothrix is nonpathogenic thread-like bacteria, much longer and thinner than lactobacilli and lies in loops or hair balls or a plate of “spaghetti.” The presence of Leptothrix in a smear is of no clinical importance except that they are sometimes found together with trichomonads (the meatballs) but the reverse is not true. The spaghetti and meatballs prefer to be together [Figure 36]![6]

- (a) CP smear – Coccoid overgrowth – streptococci are included in the coccoid flora (a) – CP smear. (b) LBC showing the same.

OVERGROWTH OF EXOGENOUS FLORA

Coccoid organisms, in particular, need an alkaline environment for an overgrowth to occur while this pH inhibits the growth of lactobacilli. Epithelial damage and coitus with its protein-rich alkaline ejaculate are some of the factors that allow the perineal flora to gain access to the vagina. Coccoid overgrowth may be seen in the cervicovaginal smears as short rods or cocci. Staphylococci and streptococci [Figure 37] are included in the coccoid flora and may be seen in colonies or singly. It is not possible to diagnose cocci in general and specific infections like N. gonorrhoeae, by light microscopy alone. Culture is necessary if broad-spectrum antibiotics do not bring the desired clinical effect.[3]

- (a) CP smear: Granular sandy background of coccobacilli. Inset showing clue cells (×40). (b) LBC smear showing clue cells, however lacks filmy sandy background that is seen in conventional smears (×40). Presence of clue cells is a clue to shift in flora suggestive of bacterial vaginosis.

Gardnerella vaginalis (in honor of Herman Gardner) is a major cause of bacterial vaginosis (BV) a clinical condition characterized by pruritus and thin watery discharge. The exact pathogenesis of BV is still unclear. There is a replacement of Doderlein bacteria by these small stout or rod-shaped organisms accompanied by changed properties of the vaginal fluid (pH>4.5, fishy ammonia like odor, and a positive whiff test) and absence of inflammation.

G. vaginalis is a small, rod-shaped coccobacillus (Gram-negative/Gram variable, facultative anaerobe). When the vaginal pH is increased above normal, G. vaginalis adheres or glues more efficiently to the squamous cells resulting in the “clue cell” formation [Figure 38]

The entire squamous cell needs to be covered by the bacteria, and obscures the cell margins, and also gives a “shaggy” appearance to it

Furthermore, the organisms may extend past the cell edges like candle wax droppings

The clue cell is a characteristic cytologic finding in and a most reliable indicator of BV

However, other bacteria can also adhere to the squamous cells. Therefore to be considered a true clue cell, the bacteria must be tiny coccobacilli consistent with G. vaginalis. Slightly curved bacilli belong to Mobiluncus species

The background of the smear is “filmy” or “sandy” composed of coccoid bacteria

Ideally, there are no lactobacilli and no polymorphs in the smear

Enhanced cellular desquamation (caused by the toxic nature of the amines), resulting in abundant anucleate squames, is common. The squames are not hypermature (i.e. this is not hyperkeratosis)

Slight parakeratosis is common.

- (a) CP smear – Jones-Marres silver stain – all organisms take a jet black color. Smear showing jet black staining of long coiled lactobacilli – mixed cervicovaginal bacterial flora. This stain helps to discriminate coccoid Gardnerella from other short plump or round bacteria. (b) Clue cells when very few are highlighted. (c) – unveiled filaments of Candida in a “Shish kebab” (c) (×40).

In the Bethesda system 2001, a report of “Shift in vaginal flora suggestive of BV” needs to be correlated clinically to arrive at a final clinical interpretation of BV for the reason that BV is not caused by a single organism but is a clinical and polymicrobial syndrome with G. vaginalis at one end of the spectrum. The other end of the spectrum includes a mixed population of microorganisms including Bacteroides species, anaerobic cocci, Mobiluncus species, peptostreptococci, and Mycoplasma hominis and coccoid bacteria.[17] Reporting Mobiluncus species is of clinical relevance, since it implies a need for prolonged treatment with metronidazole. Factors associated with shift in vaginal flora include IUD use, douching, vaginal pessaries, spermicides, multiple sexual partners, cigarette smoking, HPV infection, and SIL. In fact, only a small number of healthy women maintain the “normal” vaginal flora consistently.

Diagnosis of BV is particularly important in pregnancy, as there is a risk of chorioamnionitis and preterm delivery if the condition is untreated. In addition, BV predisposes women to PID, infertility, preterm, or low birth weight babies and also increases susceptibility of women to other STD infections. The sensitivity of the Pap test in diagnosing BV was observed to be 43.1% and specificity was 93.6%. The high specificity makes the Pap smear an adequate diagnostic criteria when it is positive.[18] Additional typing of the bacterial flora is possible with the Jones-Marres silver stain. This stain can be done using either stained or unstained Pap smears [Figure 39].[19] Coexisting coccobacillary flora when present along with Candida is often missed with routine Pap smears and hence can be a cause of chronicity of vaginal discharge. Precise identification of both can help to prescribe specific therapy for BV. Modified technique of JM stain is helpful in easy identification of cervicovaginal flora by providing better contrast and therefore enhanced visualization.[20]

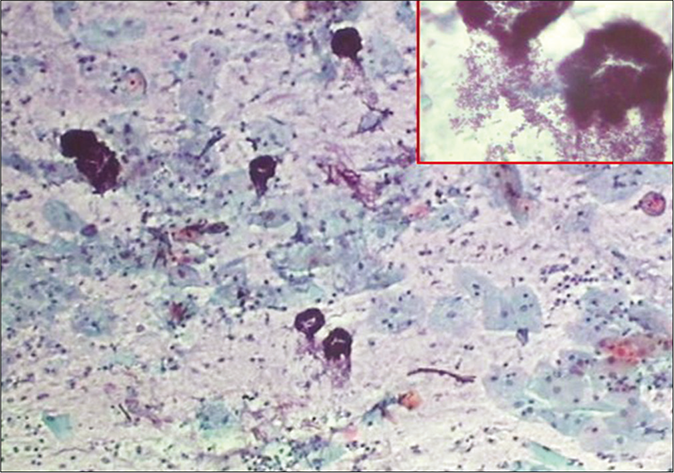

- (a) CP smear from a young female with a cervix showing hyperplastic polypoidal growth of endocervical mucosa during colposcopy. Smear showed epithelioid granulomas (red circle) and giant cells (arrow) in a dirty necrotic background (arrow). (b) Palisading of nuclei in strips of epithelioid cells (red circle). These strips were mistaken for strips of glandular cells (×40).

Neisseria gonorrhoeae: These bacteria are shaped like coffee beans in a characteristic pattern of pairs (diplococcic) whereby the round sides of the two beans face outward. They are slightly larger than the perineal flora and are occasionally identified in Pap smears. It is not possible to diagnose such specific bacterial infections by light microscopy alone. Culture is essential. Gonococci cause the cosmopolitan venereal disease gonorrhea. The infection may extend higher up leading to endometritis or salpingitis.

Calymmatobacterium (Donovania) granulomatis can be seen in scrapings of “beefy red ulcerative lesions” of the vulva, vagina, or the cervix. Smears show plenty histiocytes with multiple vacuoles containing straight or curved or oval rods. The latter can be demonstrated with the Warthin-Starry silver staining method and by Giemsa staining.

Tuberculous cervicitis and endometritis are more common in the developing countries. The cervix is involved in 0.1–0.65% of all cases of tuberculosis and 5–10% of cases in female genital tract.[21,22] The disease is secondary to tuberculosis elsewhere in the female genital tract, particularly the fallopian tubes, which, in turn, is secondary to bloodborne spread of primary tuberculosis of the lung or intestine. Clinically, papillary or vegetative/ exophytic growth at the external os may mimic cancer but does not turn white after application of 3–5% acetic acid. Clinical suspicion is raised when the patient is in the reproductive age group with history of infertility and/or irregular menstrual cycles. To detect tuberculous infection in the Pap smear from a patient with or without clinical suspicion of tuberculosis, a heightened awareness and a high index of suspicion need to be practiced. Variable amounts of any of these – granular or amorphous pale pink necrotic material in the background, epithelioid histiocytes with slender footprint-shaped nuclei, Langhan’s giant cells (with nuclei polarized at the periphery of the cytoplasm), and plenty lymphocytes with plasma cells are enough to warrant to investigate for tuberculosis [Figure 40]. Tissue diagnosis and demonstration of AFB in the tissue sections are mandatory before treatment. Palisaded strips of elongated nuclei are other clues to detect epithelioid cells. By and large tuberculous cervicitis refers to endocervicitis and therefore more abundance of glandular cells is noticed and these cells show features of endocervicitis. To an unwary, palisaded strips of epithelioid cells, can be mistaken for strips of glandular cells in the absence of other classical cytologic features. Granulomas and giant cell can be seen in other conditions such as syphilis, granuloma inguinale, lymphogranuloma venereum, foreign bodies such as suture material, cotton fibers, and in keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma associated with a giant cell reaction.[23]

- CP smear from a case of chronic cervicitis – showing aggregates of lymphocytes and few plasma cells (×40). Inset showing histopathology of the same.

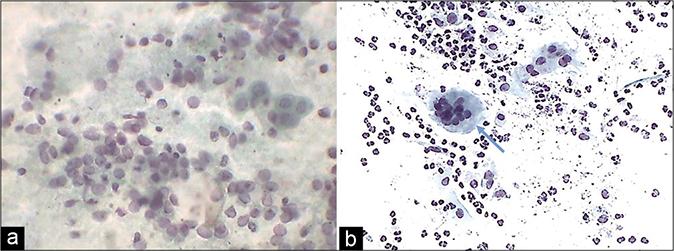

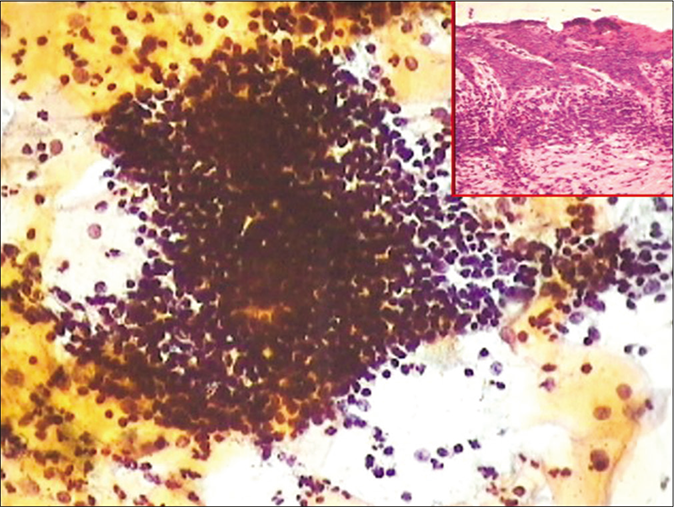

FOLLICULAR CERVICITIS

A Pap smear showing plenty lymphocytes, active germinal center cells, with tangible body macrophages is an incidental finding and may suggest chronic lymphocytic cervicitis. When seen in young women, chlamydial infection is suspected. The value of the Pap test in specifically identifying Chlamydia has been a subject of debate. The cytoplasmic vacuoles with inclusions are subjective to vast interpretative variability. Therefore, TBS has not included Chlamydia infection in its lexicon. The significance of observing monotonous population of lymphoid cells is to keep in mind the diagnostic pitfall of lymphoma. In LBC, follicular cervicitis often exfoliates dense, three-dimensional hyperchromatic crowded groups – HCGs, that is, follicles that may mimic endometrial cells, or HCGs of HSIL. The points that help in correct identification are the blotchy chromatin of lymphoid cells and also that similar single lymphoid cells may be seen dispersed throughout the smear [Figure 41].[24]

- (a) CP smear – wooly colonies of Actinomyces – “Gupta bodies” (×40). (b) LBC smear – inset is showing numerous filaments radiating from the center.

ACTINOMYCES ORGANISMS

This is an uncommon infection. Most cases are due to Actinomyces israelii. The mere presence of the organism in the Pap smear cannot be equated with infection because superficial colonization without invasive infection is very common. This species can be grown in the vaginal cultures from up to 25% of asymptomatic women.[25] They are commonly found in the cervical smears of women using IUDs and the risk increases with the duration of IUD.[26] The organism is identified in <10% (range is 0–36%) in long-term IUD users and <1% of all Pap tests. Forgotten tampons and vaginal pessaries are also favorable nidus for infection. As they are commensals of the oral cavity and the bowel, transmission to the vagina is by orogenital contact. Malodourous brownish discharge is the typical complaint. Ascending infection is one of the causes of chronic PID, infertility, and ectopic pregnancy.

The actinomycotic colonies are characteristically seen as fuzzy, dark blue, wooly balls in Pap smears and are also called as “bales of wool,” “dust bunnies,” or “Gupta bodies” (first described it) [Figure 27]

Thin radiating filaments protrude outward from a central dark blue tangled mass (due to hematoxylin stain)

These filamentous branching bacteria are Gram negative and non-acid fast

Associated features in the smear include replacement of lactobacilli with coccoid bacteria, acute inflammatory background, and neutrophils being adhered to the colonies

Splendore–Hoeppli phenomenon, due to antigen antibody reaction

The differential diagnosis of filaments in Pap smear includes Candida, Leptothrix, Aspergillus, Nocardia, and other foreign material

Fibrin, cotton, synthetic fibers, and mucin strands need to be kept in mind

Cockleburs – pseudoactinomycotic radiating arrays of golden refractile material or granules are often associated with pregnancy, may be a tempting misinterpretation. They are up to 100 um in diameter, thick, with club-shaped spokes at periphery and surrounded by histiocytes. They have no specific effect on maternal or fetal prognosis.[27]

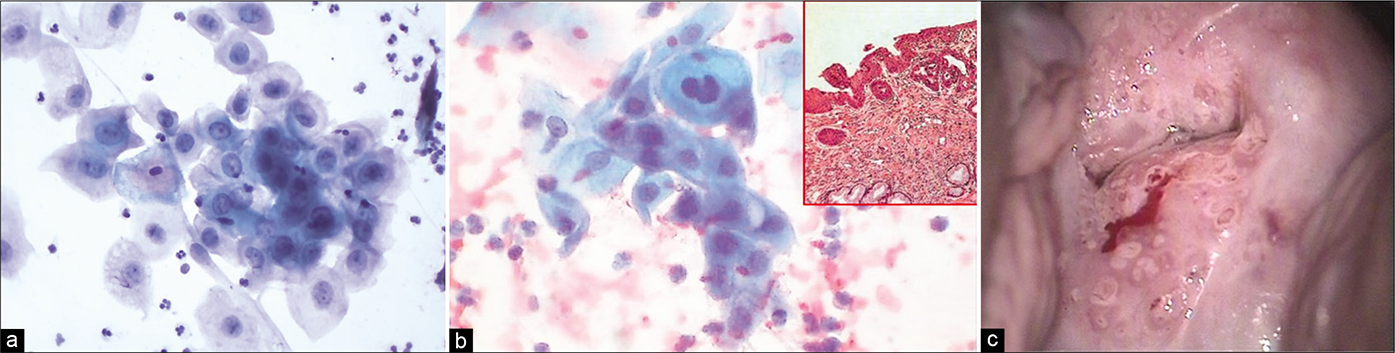

TRICHOMONAS VAGINALIS (TV)

Trichomoniasis is one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases. TV is a protozoan organism causing vaginitis and cervicitis in the females and urethritis and prostatitis in males. TV infestation can produce a variety of symptoms including frothy yellow-green or gray-white discharge with a strong odor, itching, vaginal dryness, post-coital, and intermenstrual bleeding. Trichomoniasis in pregnant women can cause premature rupture of the membranes and preterm delivery.[28] Vagina and cervix are typically congested and may show punctuate hemorrhagic spots due to surface ulceration of squamous mucosal epithelium. This gives rise to the classical appearance known as the “strawberry” cervix or vagina. The vaginal pH is often alkaline, and a coccoid flora is often present. Trichomoniasis is usually but not invariably associated with inflammation.[3,6,7]

Wet mount preparations show motile organisms

In the conventional or LBC preparations, it appears as a pale gray-green, oval, or angular (kite shaped) or pear-shaped organism that ranges from 8 um to 30 um (i.e. from the size of parabasal nucleus to parabasal cell)

Giant forms up to 150 um have been reported. There is an inverse relation between the size of the organism and the severity of infection. Neither the number of organism nor the degree of inflammation correlates with clinical symptoms and signs

The nucleus of Trichomonas is eccentric in location, pale, thin, elliptical, or crescentic and is pale staining. This nucleus is essential in distinguishing the organism from mimics such as cytoplasmic fragments and other cellular debris

Red granules may be seen in cyanophilic to gray cytoplasm

Flagella (3–5 anterior, 1 posterior) can be identified more easily in wet mounts or LBP but generally traumatized in CP smears. Phagosed RBCs and sperms can rarely be seen

These organisms multiply by binary fission

TV does not prosper in an acid pH of <5.

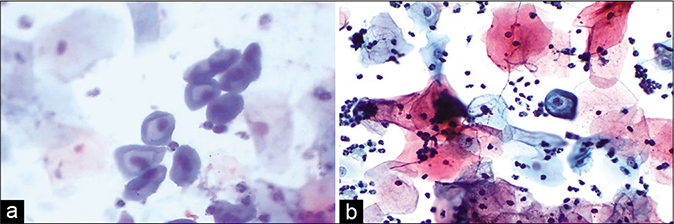

CELLULAR CHANGES

With a pronounced inflammatory reaction, the smear shows a characteristic purple color caused by the pinkish-red color of mature squamous cells and darkly stained blue polymorphs

Trichomoniasis causes non-hormonal maturation of squamous epithelium or pseudomaturation characterized by generalized eosinophilia and pseudokeratinization

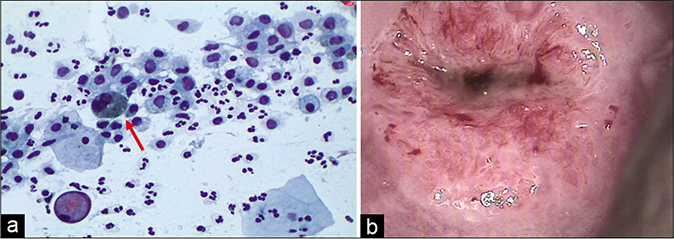

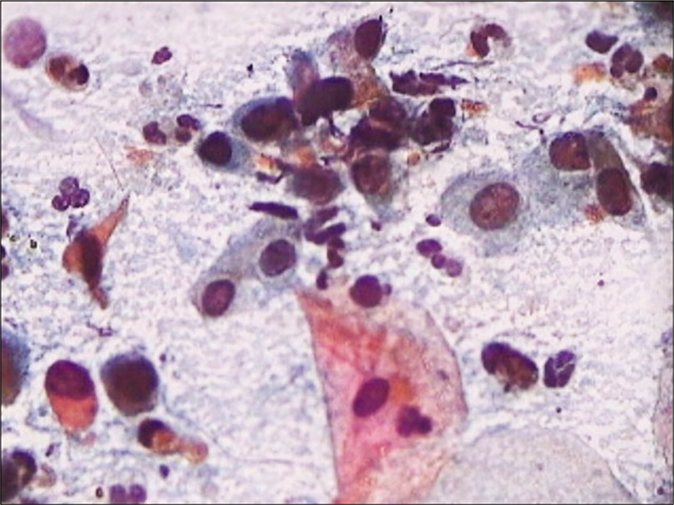

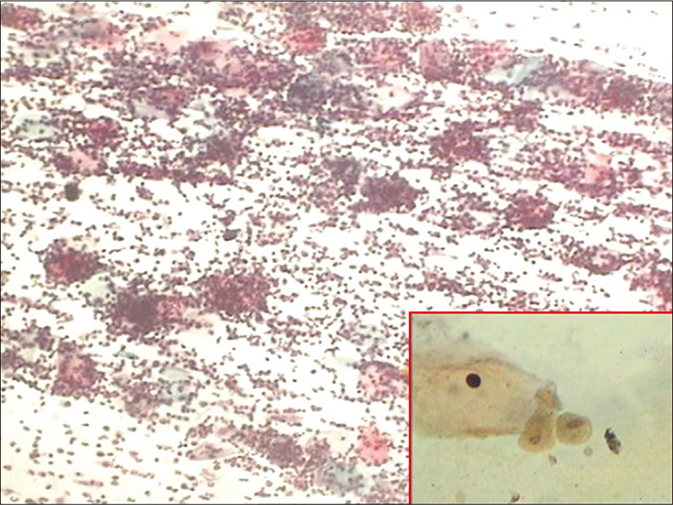

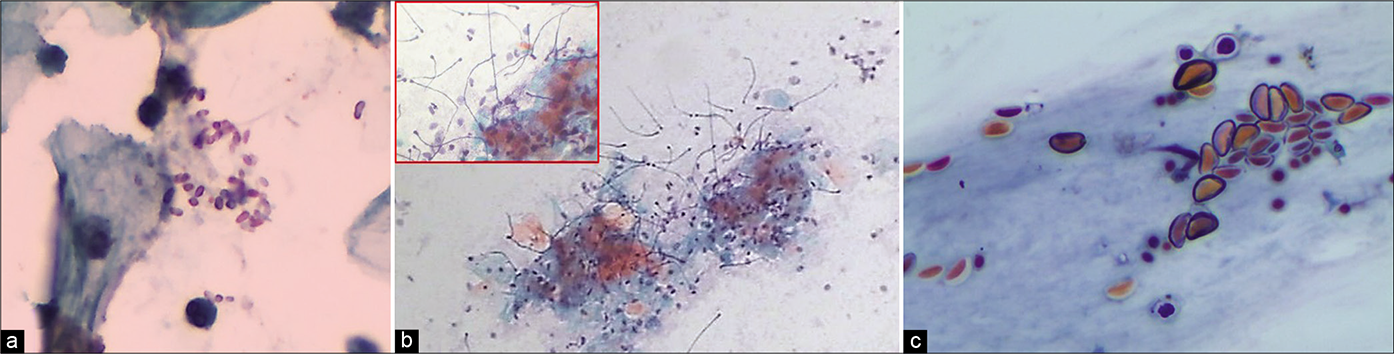

The polymorphs often than not agglomerate around organisms which, in turn, tend to attach to the surface of squamous cells or occasionally invade the cytoplasm. This phenomenon forms characteristic “cannonballs” or pus balls [Figure 42]

The background of the smear is typically “dirty” due to lysed cells, inflammation, and debris [Figure 43]

Normal flora is replaced by coccoid bacterial overgrowth

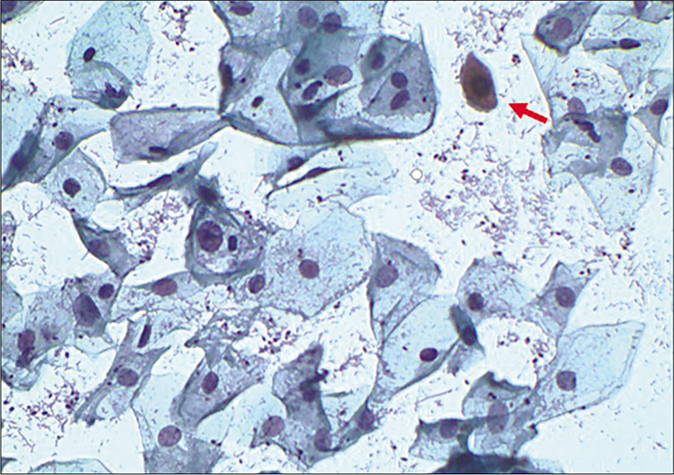

In some cases, long filamentous bacteria (Leptothrix) are seen. Inflammatory perinuclear halos or overall “moth-eaten” appearance of the cytoplasm may confuse with LSIL. However, these halos are small, not sharply defined and less than 1 / 3rd the size of the cytoplasm [Figure 44]

Nuclei of squamous cells may appear enlarged and hyperchromatic. Trichomonas infestation can lead to both false-positive and false-negative Pap test results [Figure 45].[29,30]

Secondary orangeophilia of the cell cytoplasm may be seen. These cytoplasmic and nuclear features may mimic dyskaryosis (LSIL). A repeat smear after the treatment of infection can resolve the dilemma

Atypical parakeratosis may be seen

The Pap test sensitivity averages around 60% (range of 35–85%)[31]

Culture is the current “gold standard” for diagnosis but it is not perfect[32]

Newer diagnostic techniques, such as PCR, are also available.[33]

- CP smear – cannon balls or pus balls. Leukocytes clinging to the TV attached to the surface of squamous cells (×10). Inset shows Trichomonas vaginalis with faint vesicular and rectangular nucleus.

- (a) Trichomonas vaginalis smear showing dirty cytolytic background and polychromatic staining of the squamous cells. (b) Plenty TV organisms (×40).

- (a and b) Inflammatory perinuclear halos or overall “moth-eaten” appearance of the cytoplasm may confuse with LSIL. However, these halos are small, not sharply defined, and less than 1 / 3rd the size of the cytoplasm. These are also known as pseudokoilocytes (×40). TV bodies (red arrows).

- (a and b) LBC smear – (a) multiple Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) organisms attached to the squamous epithelial cells (red arrow). Nuclei of squamous cells may appear enlarged and hyperchromatic (b and inset of a) (×40).

FUNGI

Fungi are microorganisms multiplying by spore formation or by division. The spores elongat to form pseudohyphae or may grow into long separate hyphae, which branch to form a mycelium. The rudimentary part derived from the spore is the thallus. Classification of the fungi is based on the nature and the method of the spore formation. The simplest forms of colony and spore formation are seen in the unicellular fungi. Candida is slightly more complicated in that several germinal ducts develop from the spore. The germinal ducts form long branching hyphae in which cell division occurs. New spores develop on the hyphae.

Most of the fungal infections in the vagina are caused by Candida albicans, sometimes still known as Monilia. A few cases are due to Geotrichum candidum or Torulopsis glabrata which is now classified with Candida. Other fungal elements are seen but are rare and may be usually contaminants

CANDIDA SPECIES

This dimorphic fungus is a common cause of symptomatic infection, with a white curdy non-odorous vaginal discharge and pruritus vulvae. Vulvovaginal candidiasis or “yeast infections” is extremely common in women during the reproductive years, particularly during pregnancy and the late luteal phase when the progesterone level is high.

The presence of Candida in Pap test is associated with changes in vaginal glycogen, flora, or pH. However, the incidence of candidiasis increases in women following the onset of regular sexual activity. It is estimated that up to 75% of all women will have a Candida infection sometime in their lives and 5% have chronic, recurrent infections that are difficult to treat.[34] Infections are also common when bacterial equilibrium is disturbed, for example, by broad-spectrum antibiotics or chemotherapeutic drugs. Other predisposing factors include immunosuppression, including HIV infection and diabetes mellitus, broad-spectrum antibiotics, chemotherapy, alkaline douches, and even soap, any of which can disrupt the normal vaginal flora and allow Candida to proliferate. Candidiasis is traditionally not considered as a STD because it can occur in virgins and Candida can be a part of normal vaginal flora. The presence of Candida in the Pap test does not necessarily indicate a clinically significant infection nor does absence exclude it. Therefore, clinical symptoms and clinical impression play an important and decisive role in determining whether therapy is necessary. Clinical findings include itching, red, inflamed mucous membrane, and discharge that is characteristically thick and white, like cottage cheese, but not malodorous. Complications are rare.

MORPHOLOGY

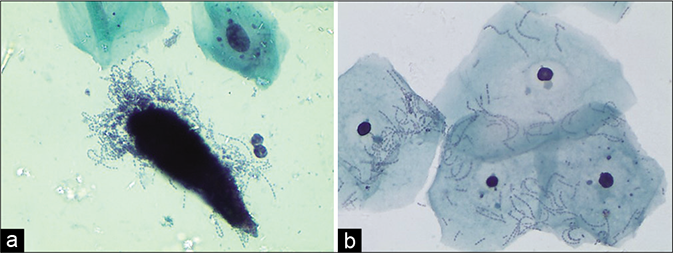

In general, a conventional smear or LBP with squamous cells, distributed in thick cakes or plaques, is a strong clue to the presence of candida as is the curdy discharge clinically.

The smear shows pseudohyphae and yeasts. The latter are pink and measure 3–7 um, and may show budding more often than not. The pseudohyphae (formed by branching chains of elongated buds giving an appearance of septation) stain pale pink or blue and are surrounded by a small clear halo[6]

The pseudohyphae at times are skewed up with mature squamous cells giving a “shish kebab” appearance. These pseudohyphae appear to protrude like stick from the stacks of squamous cells. This is because the organisms invade and grow within the squamous epithelium [Figure 46]

The quantity of the fungus in a smear has no bearing on the severity of symptoms. The fungus when seen with or without inflammatory exudate should be reported, stating the extent and whether in the form of spores or hyphae, to enable clinical correlation [Figure 47]

The close mimics of yeasts are the broken lobes of neutrophils but the regular oval shape of the yeasts and budding help to discriminate between the two

The other mimics of spores include degenerate red blood cells and streaks of mucus may be mistaken for hyphae

The reactive changes seen in the squamous cells include nuclear enlargement, orange staining of the cytoplasm, perinuclear halos, and at time two-tone cytoplasm. At times, these changes may mimic ASC-US or more [Figure 48]

Lactobacillosis is often associated with plenty of Candida yeasts as both prefer an acidic environment [Figure 44]. A polymicrobial flora and fauna is a common finding in women with chronic white discharge [Figure 49]

Up to 90% of yeasts infections are due to C. albicans. If only pseudohyphae are seen consider Geotrichum candidum, if only yeasts are seen, consider Torulopsis (Candida glabrata), a much less common infection. Spores of variable size (2–8 um) with unilateral gemmation and perinuclear halo is seen in these with the absence of hyphae [Figure 50]

Morphology alone is not enough to identify the species and culture may be required, but probably not important because therapy is identical

Other Candida group of organisms that cannot be qualified without culture [Figure 51]

Saprophytic fungus, pollens or similar contaminants, can be seen in around 20% of cases either as spores or pseudohyphae and is difficult to qualify. In the smear, these contaminants are seen lying between or on top of squamous cells. These may be totally unrelated to the exudate and generally are seen in the clean areas of the smear [Figure 52]

Presence of extraneous material like glove powder, jelly like material seen as metachromatic globules, fecal matter, limbs of mites, and variety of crystals may compromise the quality of smear. Recognizing these contaminants and reporting them should be done to justify a repeat smear [Figure 53].

- (a) CP smear – shish kebab appearance in Candida infection (×10). (b) LBC smear – squamous cells are skewed on to the branching filaments of candida (×40). (c) LBC smear – squamous cells are skewed on to the branching filaments of Candida (×40). (d) JM stain – smear showing unveiled jet black pseudohyphae of Candida in the shish kebab (×40)

- CP smear – budding yeasts of Candida in a smear devoid of inflammatory cells. Inset: Same smear with JM silver stain showing jet black budding yeasts of Candida (×40).

- CP smear – lactobacilli and Candida grow in an acidic environment with or without inflammation. Reactive cellular changes as nucleomegaly, perinuclear haloing, and dyskeratosis (red arrow) are seen in this smear (×40).

- (a) CP smear – polymicrobial flora – smear showing coccobacilli, budding yeasts of Candida and lactobacilli. (b) Pseudohyphae of Candida along with thin delicate filamentous of Leptothrix (arrow) (×40).

- (a) CP smear- Candida glabrata is characterised by a halo around each yeast and absence of hyphae (×40). (b) CP smear – smear shows contaminant fungus mimicking Candida glabrata. However, clear capsule is missing.

- CP smear – Other candida group of organisms. (a) Long slender branching and tapering filaments. (b) globular budding yeasts with empty centre. (c) budding yeasts with central dot, when present in the smear can be reported as Candida group of organisms seen . Culture is essential to further qualify them (×40).

- Pollens and contaminant fungi that cannot be qualified any further may be mentioned in the report. (a) Non-budding short and stout bacilli. (b) May be Pollens with refractile capsule. (c) Long fungi with bulbous end (×40).

- Extraneous material: (a) Limbs of mites. (b) May be faecal matter. (c)Refractile talc particles with globule of jelly material used during per vaginal examination. (d) Stacks of rectangular golden crystals (×40).

HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS

The neurodermotropic herpes viruses (Greek meaning “to creep” as in serpentine) – herpes simplex Type I and Type II have a predilection for the genital mucosa and are acquired by sexual contact. Clinically widespread vesicles, ulcers, and small pustules may coalesce and persist for around 2 weeks or till they heal. HSV may affect the cervix alone and this cervicitis is associated with both systemic and local symptoms. After an attack, the disease is self-limiting and the virus assumes a state of latency, usually in the dorsal root ganglia of the lumbosacral plexus. HSV may affect the cervix alone, without involving the external genitalia and these patients may be asymptomatic. At 1 time, HSV infection was suspected to have a role in cervical carcinogenesis. But now, it is doubtful. However, it remains a co-carcinogenic factor.[35]

The prevalence of herpes infection is almost 20 times higher in women attending genitourinary clinics than in women attending clinics for obstetrics and gynecology. Herpes simplex-related viral changes are relatively rare in Pap smears (around 1 in 4000).

MORPHOLOGY

The virus affects both the ecto- and the endo-cervical cells but more commonly the squamous epithelium (of the skin, vagina, and cervix) than the endocervical epithelium. However, because of cell distortion, it is difficult to identify the cell type in the later stages

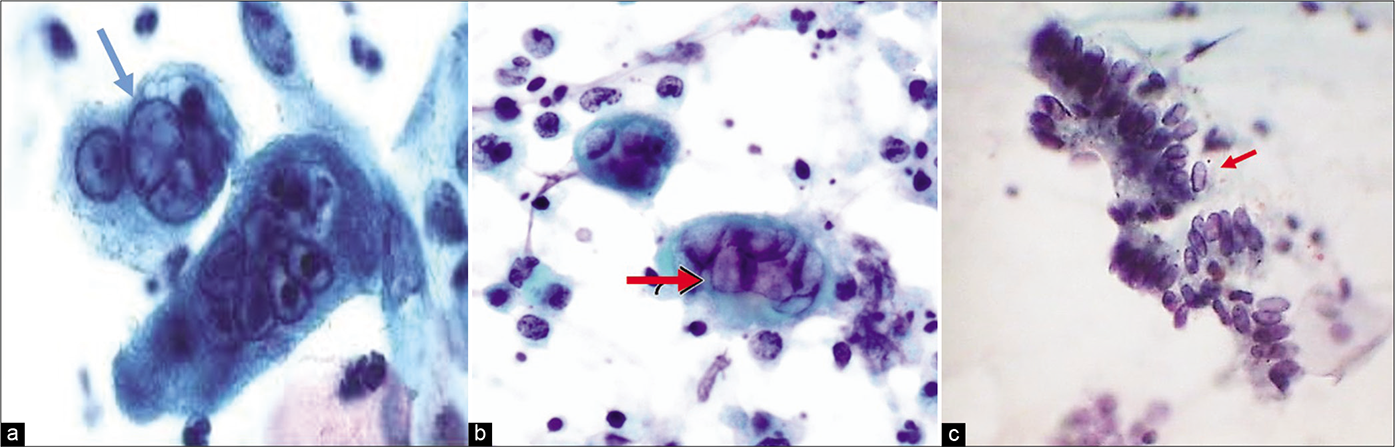

The key nuclear features may be remembered as the three Ms: Multinucleation, molding, and margination of nuclear chromatin

The pathogenesis involves three stages. In the first stage, there is an increased granularity in epithelial nuclei which may mimic degenerative nuclear features

The second stage is marked by the inception of “ground-glass” appearance of the nuclei caused by the swelling of the viral material in the nucleus surrounded by a distinct nuclear membrane [Figure 54]. These viral particles, of the size of 150 nm in diameter, are concentrated mainly in the nucleus, although cytoplasmic particles and membrane budding are a part of the picture. The ground glassing or homogenization of the nuclear contents is preceded or accompanied by nuclear vacuolization and can be easily demonstrated by electron microscopy. The cytoplasm becomes dense and basophilic

In the third stage, the nucleus contains an “acidophilic inclusion body” that is condensed viral particles that are surrounded by a clear zone within the nucleoplasm, also known as the Cowdry Type A intranuclear inclusion. These inclusion bodies, also considered by the virologists as the “tombstones,” are simply markers of impending cell death

As the nuclear changes progress, simultaneously, there is “multinucleation” (up to 60 um) and along with “nuclear molding” without overlap giving the appearance of a stack of coins [Figure 55]. This is an important differentiating feature from other giant cells such as the histiocytic, endocervical, trophoblastic, or syncytial giant cells seen in pregnancy and malignancy, where there is a significant nuclear overlap and lack of ground-glass nuclei and/or eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions

Mononucleated infected cells with enlarged swollen, ground-glass nucleus, and thick but smooth nuclear membrane may also be conspicuous and need to be differentiated from HSIL cells

Immunoperoxidase techniques and DNA in situ hybridization, PCR is reliable for the confirmation of HSV II infection both in cytology smears and histopathology sections.

- CP smear – (a and b)Ground glass appearance of nuclei (red arrows) and intranuclear inclusions seen in HSV infection. (c) These early changes can also be seen in glandular cells (×40).

- (a and b) LBC smear – Herpes Simplex virus infection. Pap smear showing multinucleation, margination of chromatin, and moulding of nuclei.

The clinical significance of diagnosing this infection is that the patients are at risk of having other STDs, they may have a concomitant CIN, they may mimic invasive cervical cancers when these herpetic lesions are necrotic, and finally, there is a risk, albeit low, of transvaginal mother to fetal transmission which may be potentially fatal.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Prajakta Sathawne, Dr. Aishwarya Warke.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

AFB – Acid fast bacilli

AGUS – Atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance

ASC-H – Atypical squamous cells cannot rule out high grade lesion

ASCUS – Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

BV – Bacterial vaginosis

CIN – Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

CMV – Cytomegalovirus

CP – Conventional Pap smear

DNA – Deoxyribonucleic acid

HCGs – Hyperchromatic crowded groups

HPV – Human papilloma virus

HSIL – High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

HSV – Herpes simplex virus

IUCD – Intrauterine contraceptive device

JM – Jones Marres silver stain

LBC – Liquid based cytology

LBPs – Liquid based preparations

LSIL – Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

N/C – Nuclear/Cytoplasmic ratio

PCR – Polymerase chain reaction

PID – Pelvic inflammatory disease

RBCs – Red blood cells

SCJ – Squamocolumnar junction

SILs – Squamous intraepithelial lesions

STD – Sexually transmitted diseases

TBS – The Bethesda System

TV – Trichomonas vaginalis

TZ – Transformation zone

WNL – Within normal limit

References

- Vaginal microbial flora: Composition and influences of host physiology. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96(Suppl 6):926-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical cytology findings in women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Diagn Cytopathol. 1993;9:508-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Normal vulva, vagina and cervix: Hormonal and inflammatory conditions In: Gray W, McKee G, eds. Diagnostic Cytopathology (2nd ed). London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2003. p. :651.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic manifestations of cervical and vaginal infections. I Epithelial and inflammatory cellular changes. JAMA. 1985a;253:989-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Chapter-Microbiology Inflammation, and Viral Infections: In Comprehensive Cytopathology. (3rd ed). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2008. p. :91-129.

- [Google Scholar]

- The pap test: Benign cellular changes In: The Art and Science of Cytopathology (2nd ed). United States: American Society for Clinical Pathology Press; 2012. p. :29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benign disorders of uterine cervix and vagina: Inflammatory process of female genital tract In: Koss’s Diagnostic Cytology and its Histopathologic Bases (5th ed). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006. p. :253.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histiocytes and histiocytic reaction in vaginal cytology. A survey of the risks of false positive diagnosis. Cancer. 1961;14:1223-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The cytologic diagnosis of tissue repair in the female genital tract. Acta Cytol. 1971;15:133-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Significance of atypical repair in liquid based gynecologic cytology: A follow up study with moleculr analysis for human papillomavirus. Cancer. 2003e;99:141-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atypical reparative change on cervical/vaginal smears may be associated with dysplasia. Diagn Cytopathol. 1996;14:374-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reparative changes and the false positive/false-negative papanicolau test: A study from the College of American pathologists interlaboratory comparison program in cervicovaginal cytology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001b;125:134-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benign cellular changes in Pap smears. Causes and significance. Acta Cytol. 2001;45:5-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lactobacilli mediated control of vaginal cancer through specific reactive oxygen species interaction. Med Hypotheses. 2001;57:252-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accumulation of polyphosphate in Lactobacillus spp and its involvement in stress resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:1650-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial vaginosis: Comparison of Pap smear and microbiological test results. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:857-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Visualisation of vaginal flora in cervical smears using a modified microwave silver staining method. Histochem J. 1998;30:75-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microwave assisted silver stain for Pap smear to improve the identification of coccobacillary flora. Arch Cytol Histopathol Res. 2019;4:31-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tuberculosis cervicitis mimicking cancer cervix: A case study. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2014;19:75-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytological diagnosis of tuberculous cervicitis: A case report with review of literature. J Cytol. 2012;29:86-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic detection of tuberculous cervicitis: A report of 7 cases. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:594-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytological features of chronic follicular cervicitis in liquid based specimens: A potential diagnostic pitfall. Cytopathology. 2002;13:364-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pelvic actinomycosis: A review and preliminary look at prevalence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:265-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic findings in Pap smears with actinomyces-like organisms. Acta Cytol. 2005a;49:257-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- crystalline bodies in cervical smears: Clinicopathologic correlation. Acta Cytol. 1993;42:149-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in endocervical and ectocervical smears. Diagn Cytopathol. 1996;14:273-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic features of Squamous cell carcinoma in ThinPrep slides: Evaluation of cases that performed poorly versus those that performed well in the college of American pathologists interlaboratory comparison program in cervicovginal cytology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004b;128:403-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distraction index: Part I: The elusive trich (editorial) In: Diagn Cytopathol. Vol 21. 1999. p. :367-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The detection of genital tract infections by Papanicolaou stained tests. Cytopathology. 2006;17:317-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical impact of identifying Trichomonas vaginalis on cervicovaginal (Papanicolaou) smears. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;24:195-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparative evaluation of the papanicolaou test for the diagnosis of trichomoniasis. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:694-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chronic recurrent vaginal candidosis: Easy to treat, difficult to cure. Results of intermittent treatment with a new oral antifungant. Eur J Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Biol. 1990;35:75-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accuracy of herpes simplex virus detection in liquid-based (SurePath) Papanicolaou tests: A comparison with polymerase chain reaction. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:94-103.

- [Google Scholar]