Translate this page into:

Tibial bone metastasis as an initial presentation of endometrial carcinoma diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology: A case report and review of the literature

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. However, bony metastasis is infrequent and exceptionally rare as the initial presentation. We report a case of a 77-year-old female with a clinically silent endometrial carcinoma who presented with a left tibial metastasis as the first manifestation of her disease. Ours is only the third case diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology, and the first to detail the cytomorphologic features of metastatic endometrial cancer to bone. These microscopic findings, including three-dimensional cohesive clusters with cellular overlapping and cuboidal to columnar cells exhibiting low nuclear: cytoplasmic ratios and partially vacuolated cytoplasm, differ significantly from those of endometrial carcinoma on a Papanicolaou test. The tumor bore similarity to the more commonly encountered metastatic colon cancer, but immunohistochemical staining enabled reliable distinction between these entities. A review of osseous metastases of endometrial cancer demonstrates a predilection for bones of the lower extremity and pelvis with a predominance of the endometrioid histologic subtype. In about a quarter of the cases, the bony metastasis was the first manifestation of the cancer. FNA was an effective diagnostic modality for this unusual presentation of a common malignancy. Awareness of this entity and its differential diagnosis is essential for accurate and timely diagnosis.

Keywords

Bone metastasis

endometrial carcinoma

fine needle aspiration cytology

BACKGROUND

In the United States, endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy and the fourth most frequent cancer in women after breast, lung, and colorectal cancers.[1] About 90% of women present with abnormal uterine bleeding, and approximately 72% of endometrial cancers are limited to the uterus (Stage I) at the time of diagnosis.[1] Only 3% of cases present with Stage IV disease.[1] Bone metastasis is infrequent, with a 2–6% observed incidence.[2] In addition, bone involvement as the initial manifestation is exceptionally rare, and only a few cases have been reported. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first description of fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytologic features of metastatic osseous endometrial adenocarcinoma.

CASE REPORT

Clinical history

We report a case of a 77-year-old Japanese woman with a history of diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and abdominal shingles, who presented to her physician with left leg swelling and pain with no other associated symptoms. Upon examination, there was a tender palpable lesion 1.5 cm × 1.0 cm in the anterior aspect of her left leg. Neurological examination was unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lower extremities revealed a distal left tibial lesion measuring 11.0 cm × 2.1 cm with focal extraosseous extension [Figure 1].

- Magnetic resonance imaging of lower extremities demonstrating a left tibial intramedullary lesion with focal extraosseous extension

Fine- needle aspiration findings

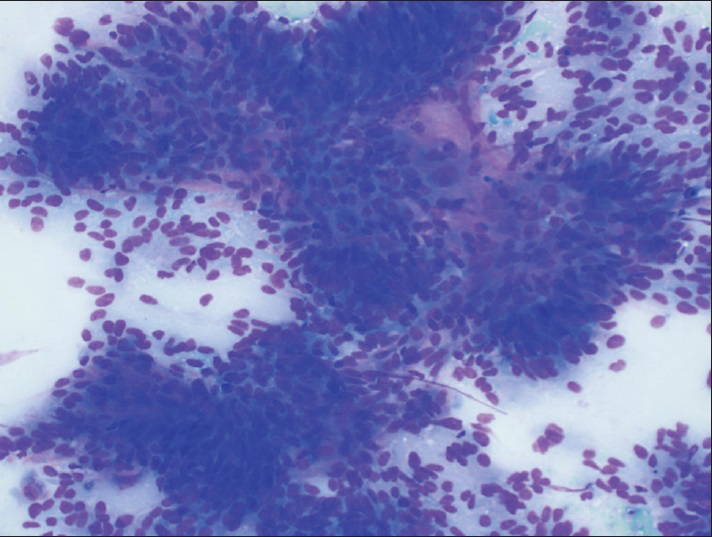

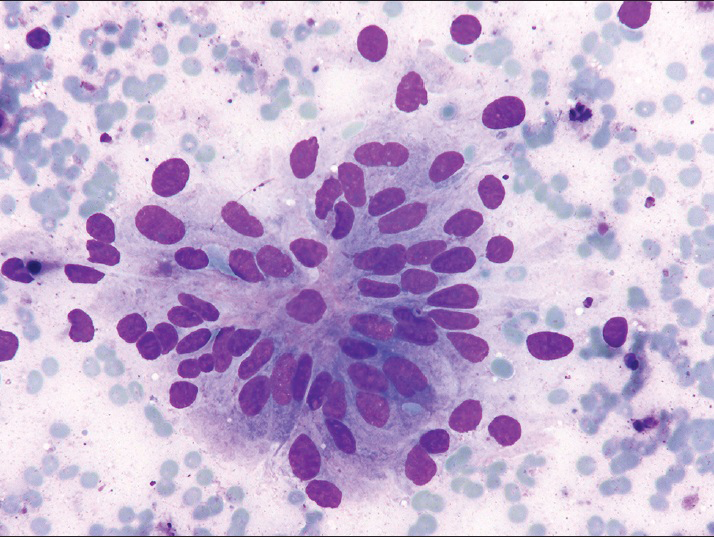

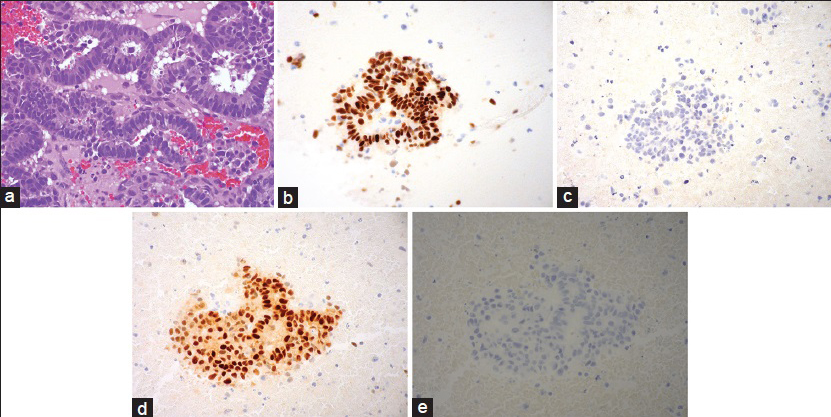

Fine-needle aspiration was performed on the patient's left leg mass using a 21 gauge needle. Air-dried smears were prepared and stained on-site with the Diff-Quik stain. Some of these slides were later destained and restained with the Papanicolaou (Pap) stain. The remainder of the specimen was placed in formalin for a cell block preparation. The cytologic smears showed a moderately cellular yield, with the tumor arranged mostly in three-dimensional cohesive clusters with cellular overlapping and architectural disorder [Figure 2]. A few single tumor cells were noted in the background. The tumor assumed the form of predominantly cuboidal to columnar cells exhibiting low nuclear: cytoplasmic (N:C) ratios and partially vacuolated cytoplasm. The cells contained elongated nuclei showing mild to moderate nuclear pleomorphism with finely dispersed chromatin and occasional prominent nucleoli [Figure 3]. No papillary formations or clear cell features were noted. The cell block preparation revealed tumor glands arranged in frequent cribriform structures lined by crowded columnar cells [Figure 4]. Immunohistochemical staining showed diffuse positivity of the neoplastic cells for cytokeratin 7, estrogen receptor, and paired box gene 8 (PAX-8). Staining was negative with cytokeratin 20, CDX-2, thyroid transcription factor-1, napsin-A, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, and mammaglobin. A diagnosis of metastatic endometrial carcinoma was rendered.

- Fine-needle aspiration, left leg, Diff-Quik (×200), showing a cellular yield of cohesive, three-dimensional tumor clusters with cellular overlapping and architectural disorder

- Fine-needle aspiration, left leg, Diff-Quik (×400), columnar tumor cells arranged in glandular configuration with elongated nuclei, mild to moderate nuclear pleomorphism, and finely dispersed chromatin

- (a) Fine-needle aspiration, left leg, cell block preparation with cribriform tumor glands (H and E, ×400). (b) Estrogen receptor (×400). (c) Thyroid transcription factor-1 (×400). (d) Paired box gene 8 (×400). (e) Mammaglobin (×400)

Follow-up and further management

Based on the cytological diagnosis, the patient then underwent systemic work-up including computerized tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen, pelvis, and chest. The abdominal CT showed a 4.2 cm fluid density in the uterus, thought to be within the endometrial canal. A pelvic CT scan, as well as a bone scan, demonstrated a 6.0 cm × 5.2 cm enhancing soft tissue mass destroying the right pubic symphysis. Thoracic imaging revealed bilateral pulmonary nodules measuring up to 4 mm.

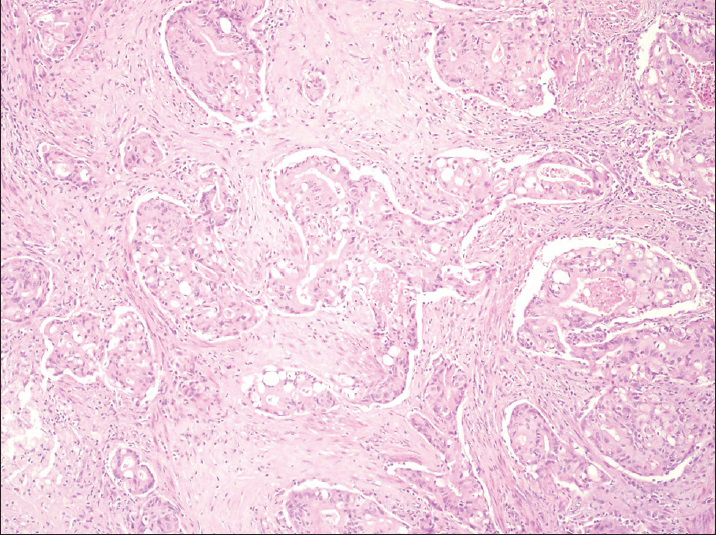

Endometrial biopsy performed 2 weeks after the initial FNA revealed endometrioid adenocarcinoma with focal squamous differentiation. Soon thereafter, the patient underwent radiation to the left tibia and pelvis followed by total abdominal hysterectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection. Gross examination showed a 143 g uterus with a tan, firm tumor lesion measuring 4.3 cm × 3.2 cm, occupying the anterior and posterior fundus and body. Cross sections demonstrated tumor invading to a maximal depth of 25 mm out of 26 mm of the myometrial thickness. Microscopic examination confirmed the diagnosis of FIGO grade 2 endometrioid adenocarcinoma, characterized by myoinvasive neoplastic cribriform glands similar to that seen in the patient's bone FNA [Figure 5]. Immunohistochemical staining of the uterine endometrial cancer showed a staining profile similar to that seen in the osseous metastasis, including positivity for cytokeratin 7, estrogen receptor, and PAX-8. No lymph node metastases were detected.

- Hysterectomy specimen showing cribriform tumor glands of endometrioid adenocarcinoma infiltrating the myometrium. H and E (×200)

The patient declined radiation or chemotherapeutic treatment, and was started on hormonal therapy with regular follow-up. Two years after her initial FNA diagnosis, she is asymptomatic, and serial bone scans demonstrate therapeutic response of her osseous metastases. A CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis show no progression of the bony lesions or development of new metastases.

DISCUSSION

Fine-needle aspiration of bone lesions was first described by Martin and Ellis.[3] Bommer et al.[4] reported a series of 450 bone FNA biopsies conducted over a 17-year period. Of their cases interpreted as cytologically malignant, 175 (81%) were metastatic malignancies. About 118 (67%) of these metastases were adenocarcinomas, originating in descending order from the breast, lung, prostate, and gastrointestinal tract.[4] No osseous metastases from a female genital tract primary were observed in their series. Additional studies[567] collectively described the features of 333 patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma to bone. The primary origins of cancer were lung (28%), genitourinary tract (26%), breast (13%), and gastrointestinal tract (11%). Only one of these three articles[6] noted osseous metastases from gynecologic primaries, which accounted for only 4% of their entire cohort. Furthermore, Kehoe et al.[8] reported an investigation of 15,230 patients with metastatic cancer to bone from multiple sources. Of their patients, only 21 (0.1%) were from endometrial primaries. Therefore, endometrial cancer, as well as other female genital tract malignancies, rarely metastasizes to bone.

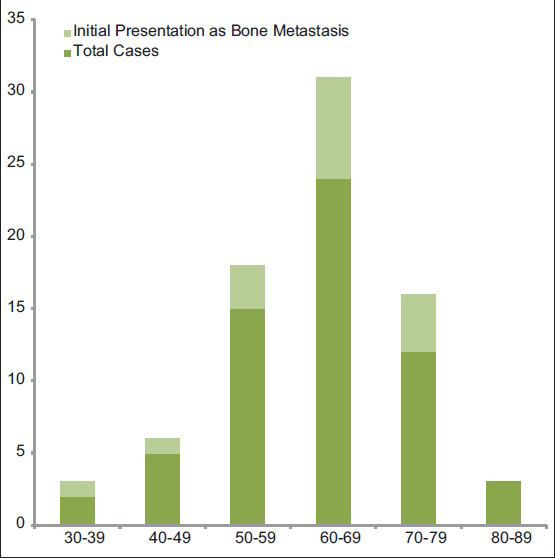

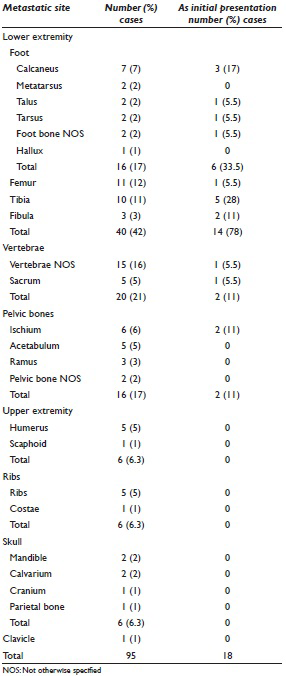

A further review of the literature revealed 38 articles[2891011121314151617181920212223242526272829303132333435363738394041424344] between 1967 and 2011, describing 61 patients with metastatic endometrial cancer to bone. Including our case, these patients ranged in age from 32 to 86 years, with an average age of 62 years (standard deviation 10.8 years) [Figure 6]. Forty-one (67%) of these patients presented with metastasis in a single osseous location, whereas 20 (33%) developed multiple bony metastases. The most frequent sites of involvement were the lower extremity bones (42%), most notably the foot bones (17%), followed by femur (12%) and tibia (11%) [Table 1]. Other skeletal metastases involved the vertebrae (21%) and pelvic bones (17%). Metastases to other bones, including upper extremity bones, ribs, and skull were far less common. Patient age had no bearing on the pattern of distribution of these bony metastases.

- Age distribution of metastatic endometrial cancer to bone by decade

Including our patient, a total of 16 (26%) patients presented with bone metastasis as the initial presentation of malignancy. Their age distribution did not differ from other endometrial cancer patients with bony metastases [Figure 6]. Neither did the location of the osseous metastases [Table 1], except that the lower extremity bones comprised a much larger percentage (78% vs. 42%), while the vertebrae and pelvic bones were less frequently represented. No other bones were noted to be involved in these patients.

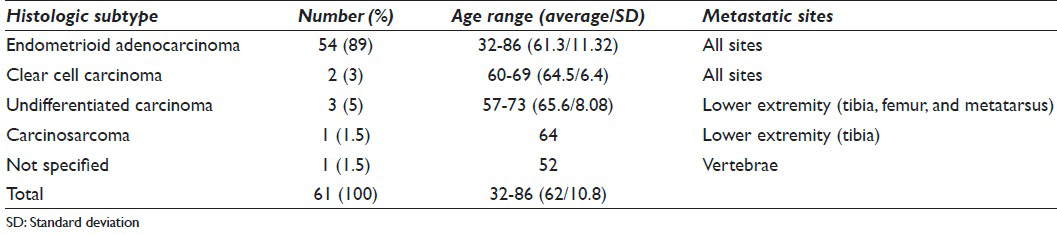

Of the 55 cases with a reported tumor grade, the majority (53%) were poorly differentiated, with the remainder well (22%) and moderately (25%) differentiated. The tumor histologic subtypes were known in 60 (98%) cases and were most commonly endometrioid adenocarcinomas (89%) [Table 2]. Collectively, the higher grade endometrial cancer subtypes (clear cell carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma) comprised <10% of cases. The patients with metastatic endometrioid adenocarcinoma exhibited a wider age range than their higher grade counterparts [Table 2]. Furthermore, undifferentiated carcinoma and carcinosarcoma were noted to metastasize only to the lower extremity bones, whereas metastatic endometrioid and clear cell cancers were reported in other osseous sites [Table 2].

A total of 57 (93%) cases reported the initial tumor stage and included 23% stage I, 7% stage II, 19% stage III, and 51% stage IV cancers. A total of 25 patients (41%) also developed metastases outside of the bone. Of the cases where these extraosseous metastatic sites were detailed, they included nine to lung,[142023242628313242] three to vagina,[21735] and two to kidney.[1423]

Totally, 46 (75%) of the bone metastases were confirmed by biopsy, 12 (20%) were found by imaging studies, and only 3 (5%) were diagnosed by FNA cytology. Of these latter cases, ours is the only report in which the cytologic features of metastatic endometrioid adenocarcinoma to bone are fully described. These features differed significantly from those of endometrial carcinoma detected on a Pap test. In the latter, the Pap, usually, exhibits only a scant yield of small, tightly cohesive, round clusters of neoplastic endometrial cells.[45] These cells tend to be rounded or oval with high N:C ratios, scant cytoplasm, and ill-defined cell borders. The nucleus appears enlarged with small to prominent nucleoli and irregular chromatin distribution.[45] In contrast, our FNA revealed a moderately cellular smear of larger, three-dimensional cohesive cell clusters with crowding and overlapping [Figure 2]. Most of the tumor cells were columnar in shape with elongated nuclei and low N: C ratios [Figure 3].

Among our cytologic differential diagnoses was metastatic colonic carcinoma, which may demonstrate similar morphologic features and is far more commonly encountered. In the aforementioned series of metastatic carcinoma to bone diagnosed by FNA,[567] metastatic gastrointestinal cancer was encountered in 11% (range 0–17%) of the cumulative total of 333 patients, versus only 1% for gynecological metastases (range 0–4%). In cytologic specimens of metastatic colon cancer, there are groups of disordered cells with glandular or micro-acinar arrangements.[46] The tumor cells vary in shape from tall columnar with elongated, cigar-shaped nuclei, to more rounded cells with ovoid nuclei. Characteristic distinguishing cytomorphologic features of metastatic colon cancer include the presence of a dirty necrotic background and terminal bar-like densities at the apical border.[46] Immunohistochemistry is extremely useful in making this distinction as was evident in our case.

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma may also originate in the ovary. Although the literature contains a few reports of the cytologic features of this histologic variant of ovarian cancer,[47484950] our search failed to detect a single FNA case of this entity metastasizing to bone. Nevertheless, this malignancy is worth mentioning as one of our cytologic differential diagnostic entities. Ramzy and Delaney[47] observed ovarian endometrioid carcinoma cells arranged mostly in sheets or clusters. The tumor cells displayed scant cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei with thick nuclear membranes as well as irregular chromatin distribution. The tumor nuclei exhibited crowding and molding, with the background described as mucoid, bloody, and containing abundant hemosiderin-laden histiocytes. Other authors have noted sheet-like arrangement of cells with light-colored cytoplasm, finely granular nuclei, relatively regular nuclear contours, and infrequent nucleoli,[48] as well as clusters of neoplastic columnar cells with elongated nuclei forming gland-like structures.[49] These cytologic features bear some similarity to those of our metastatic endometrioid carcinoma of endometrial origin and likewise differ significantly from those of endometrial carcinoma observed on Pap tests.

Fine-needle aspiration diagnosis of metastatic endometrial carcinoma to sites other than bone have been reported,[5152535455565758] including abdominal wall, breast, pleura, pancreas, tongue, and thyroid. Most of these metastatic tumors were endometrioid carcinomas, with some serous papillary cancers and a few clear cell carcinomas. In the metastases exhibiting the endometrioid histology,[515253] the cytomorphologic features were similar to our case. The tumor cells were arranged in crowded pseudostratified clusters with occasional lumen or pseudoglandular formations.[5152] Papillary architecture with fibrovascular cores was also described.[5152] Other notable features included nuclear palisading[51] and bland cells with apocrine features.[53]

CONCLUSION

Although endometrial cancer is the most commonly encountered gynecologic malignancy, it only rarely metastasizes to bone. In almost one-quarter of cases (26%), bony metastasis was the presenting manifestation of the disease. Metastatic endometrioid carcinoma (89%) was the most common histologic cancer subtype observed in the bone. Lower extremity and pelvic bones were the most frequently involved osseous sites, accounting for 58% of all reported loci. Only 3 (5%) of the 62 cases reported in the literature were diagnosed by FNA cytology, including our case. Ours is the sole report where the cytologic features of metastatic endometrial carcinoma to bone are fully detailed. These morphologic features differ significantly from those of endometrial carcinoma on a Pap test but bear much similarity to endometrial cancer metastasizing to other distant sites, as well as metastatic colonic cancers. FNA was an easy and reliable diagnostic modality for this unusual presentation of a common malignancy. Thus, the cytopathologist must be aware of this entity, in order to promptly and accurately diagnose this rare manifestation.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author. Each author participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is a case report without patient identifiers, our institution does not require approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) (or its equivalent).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

FNA = Fine-Needle Aspiration

Pap = Papanicolaou

PAX-8 = Paired Box Gene 8

CT = Computerized Tomography

IRB = Institutional Review Board

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Endometrial carcinoma and an unusual presentation of bone metastasis: A case report. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82:216-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis and management of bone lesions: A study of 450 cases. Cancer. 1997;81:148-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic role of fine-needle aspiration of bone lesions in patients with a previous history of malignancy. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;26:380-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytological diagnosis of skeletal lesions. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy in 110 tumours. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:673-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration cytology of bone: Accuracy and pitfalls of cytodiagnosis. Cancer. 2000;90:47-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinicopathologic features of bone metastases and outcomes in patients with primary endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117:229-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolated metastasis of the tarsal scaphoid bone in the course of cancer of the uterine body. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1967;34:650-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Osseous metastasis revealing endometrial cancer. Bull Fed Soc Gynecol Obstet Lang Fr. 1967;19:352-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metastasis to the fibula from endometrial carcinoma. Report of 2 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1967;29:803-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the calcaneus: Case report. J Foot Surg. 1976;15:28-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early osseous metastasis of stage 1 endometrial carcinoma: Report of a case. Gynecol Oncol. 1982;14:141-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathological fracture of right tibia, an unusual presentation of endometrial carcinoma: A case report. Injury. 1983;14:541-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolated calcaneal metastasis in a patient with endometrial adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 1991;67:1979-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial adenocarcinoma presenting as an isolated calcaneal metastasis.A rare entity with good prognosis. Cancer. 1994;73:2779-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metastatic calcaneal adenocarcinoma in a patient with uterine carcinoma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1994;45:287-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solitary metastasis in the tarsus preceding the diagnosis of primary endometrial cancer.A case report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1995;16:387-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recurrent endometrial adenocarcinoma presenting as a solitary humeral metastasis. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;59:148-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metastatic endometrial carcinoma of the foot. A case report. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1996;86:331-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Untreated endometrial adenocarcinoma: A case report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1997;18:144-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mandibular metastasis in a patient with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;72:243-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial carcinoma metastatic to the mandible: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:914-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scalp and cranial bone metastasis of endometrial carcinoma: A case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81:105-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial carcinoma presenting with an isolated osseous metastasis: A case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1997;18:492-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pain in the foot: Calcaneal metastasis as the presenting feature of endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:1067-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma in a premenopausal woman presenting with metastasis to bone: A case report and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2002;21:281-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial cancer metastasis presenting as a grossly swollen toe. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13:909-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prolonged survival time following initial presentation with bony metastasis in stage IVb endometrial carcinoma. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43:239-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- False-negative bone scintigraphy in a woman with bone metastases secondary to endometrial adenocarcinoma. Med Clin (Barc). 2003;121:119.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial carcinoma metastasis to the distal phalanx of the hallux: A case report. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2005;44:462-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Skeletal carcinomatosis in endometrial clear cell carcinoma at initial presentation: A case report. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:891-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bone metastasis as a presenting feature of endometrial adenocarcinoma: Case report and literature review. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2006;27:95-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial carcinoma bone metastases in unusual sites. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:411.

- [Google Scholar]

- Two cases of endometrial cancer diagnosis associated with bone metastasis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61:49-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term prevention of skeletal complications by pamidronate in a patient with bone metastasis from endometrial carcinoma: A case report. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:195-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial adenocarcinoma presenting with an osseous metastasis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61:200-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sacral metastasis in a patient with endometrial cancer: Case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:583-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial carcinosarcoma presenting as a tibial metastasis. Int J Clin Oncol. 2007;12:305-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solitary bone metastasis in the tibia as a presenting sign of endometrial adenocarcinoma: A case report and the review of the literature. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2007;24:87-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bilateral femur metastasis in endometrial adenocarcinoma. Saudi Med J. 2008;29:766-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rare presentation of endometrial carcinoma with singular bone metastasis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2010;19:694-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- An extremely rare presentation of relapse in endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma: Isolated metastases to the tibia and humerus. Case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2011;32:547-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epithelial abnormalities: Glandular. In: Solomon D, Nayar R, eds. The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology (2nd ed). New York: Springer-Verlage; 2004. p. :147-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration of ovarian masses. I. Correlative cytologic and histologic study of celomic epithelial neoplasms. Acta Cytol. 1979;23:97-104.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic and biologic studies of endometrioid carcinoma of the ovary. Acta Cytol. 1983;27:676-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of ovarian lesions: Is it reliable? Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2008;4:143-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Image-directed percutaneous FNAC of ovarian neoplasms. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2005;48:305-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle cytology of metastatic endometrioid neoplasms: Experience with eight cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:347-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytopathology of endometrial adenocarcinoma metastases to the breast examined by fine-needle aspiration. Am J Clin Pathol. 1982;78:559-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metastases to the breast from extramammary neoplasms.A report of six cases with diagnosis by fine needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 1996;40:1293-300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial carcinoma with recurrence in the incisional scar: A case report. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13:901-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metastatic papillary endometrial carcinoma of the tongue. Case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1992;116:965-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial carcinoma with pleural metastasis: A case report. Acta Cytol. 2006;50:697-700.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distal pancreatectomy for isolated metastasis of endometrial carcinoma to the pancreas. JOP. 2008;9:56-60.

- [Google Scholar]