Translate this page into:

Cerebrospinal fluid cytology of choroid plexus tumor: A report of two cases

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Choroid plexus tumors (CPTs) are relatively uncommon tumors of the central nervous system, constituting approximately 5% of all pediatric brain tumors. Although squash cytology of CPT has been described in literature, shedding of tumor cells into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has rarely been described. We report two such cases of atypical choroid plexus papilloma in a 5-month-old male child and a 12-year-old female child, where characteristic cytomorphology of CPT was noted in the CSF.

Keywords

Choroid plexus papilloma

cerebrospinal fluid

cytology

histology

INTRODUCTION

Choroid plexus tumors (CPTs) are uncommon neoplasms derived from choroid plexus epithelium of the ventricles and characterized by papillary and intraventricular growth.[12] Within this family of tumors, there are benign and malignant variants, typically classified as choroid plexus papilloma (CPP), atypical CPP (ACPP), and choroid plexus carcinoma (CPC).[123]

Among the CPTs, papillomas are five times more common than carcinomas and occur in the age group of newborn to children <3 years of age.[234] The lesion tends to block cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways and patients present with signs of hydrocephalus and raised intracranial pressure. However, not all disseminate or shed into the CSF.[3456] Very few cases of positive CSF cytology of CPTs are reported in the literature. We report two cases with characteristic CSF cytomorphological features of CPT in a 5-month-old male child and a 12-year-old female child.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 5-month-old male child presented with complaints of vomiting and decreased oral intake for the last 5–6 days. There was no associated fever, seizures, loss of consciousness, lethargy, or altered sensorium. No increase in head circumference was noted by the parents.

The child was delivered by full-term normal vaginal delivery, with birth weight of 3.1 kg. The post-term period was uneventful. He was on exclusive breastfeeding. The child was not able to hold his neck, roll over, cooing, bidextrous grasp for last 8–10 days. His other siblings (two sisters and one brother) were doing well. General examination showed the presence of dehydration with sunken eyes. Central nervous system (CNS) examination revealed tensed and bulged anterior fontanelle, with sutural separation and sunsetting sign. Plantar reflex was decreased, pupils dilated, and sluggishly reacting to light. The rest of the systems examined did not reveal any abnormality.

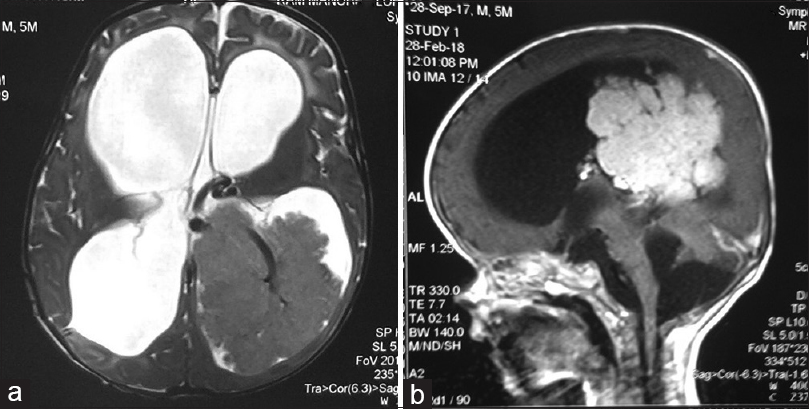

A contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed evidence of gross hydrocephalus with a large well-defined lobulated mass epicentered in the trigone occipital horn and body of left lateral ventricle showing intense homogeneous enhancement, suggestive of CPT and corpus callosum agenesis [Figure 1a and b].

- A noncontrast (a) and contrast-enhanced (b) magnetic resonance imaging showing a large well-defined lobulated mass epicentered in the trigone occipital horn and body of left lateral ventricle showing intense homogeneous enhancement, suggestive of choroid plexus tumor

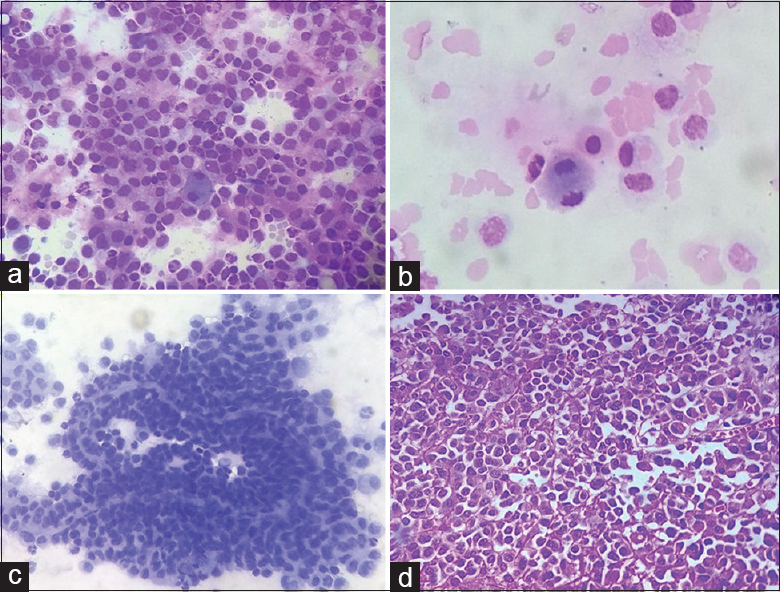

His complete blood counts and routine biochemical investigations were within normal limits. Lumber puncture was done, and 1 ml of clear fluid labeled as CSF was sent for cytopathological examination. Smears prepared were cellular and comprised atypical cells, mostly singly scattered and in syncytial clusters and very occasionally papillary fragments [Figure 2a and b]. Cells were round to oval and showed mild pleomorphism with eccentrically placed nuclei, finely granular chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, nuclear membrane indentation, and moderate to abundant amount of pale cytoplasm. Occasional mitosis and few binucleate forms were also seen [Figure 2c].

- (a) Cellular smear composed of round-to-oval atypical cells, mostly singly scattered and in syncytial clusters, showing mild pleomorphism with eccentrically placed nuclei, finely granular chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, nuclear membrane indentation, and moderate to abundant amount of pale cytoplasm (Giemsa, ×200); (b) occasional mitotic figure is noted interspersed with few tumor cells (Giemsa, ×400); (c) Papillary fragment of the tumor with fibrovascular core is noted (Papanicolaou, ×400); (d) Section showing cellular tumor composed of cells mainly in sheets with focal papillary pattern (H and E, ×400)

A final cytomorphological diagnosis of CPT was given (likely benign), in conjunction with radiological details. The patient was symptomatically managed. Ventriculoperitoneal shunt was put; however, it was unable to clear the excess of CSF. The patient succumbed to his illness within a few days; hence, biopsy or surgery could not be done.

Case 2

A 12-year-old female patient presented with a history of vomiting, fever, and headache for the last 10 days. There was no history of unconsciousness, convulsion, dizziness, or visual impairment. The patient had a history of operation for CPC 4 years back. Other systemic examination was normal. Her routine blood examination did not reveal any abnormality. Computed tomography (CT) brain showed a well-defined homogeneously enhancing lesion in the left lateral ventricle, suggestive of CPP. Lumbar puncture was done, and 3 ml of CSF was sent for cytological examination.

Smears prepared showed high cellularity comprising singly scattered round-to-oval atypical cells showing mild pleomorphism, eccentrically placed nuclei, with fine chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli and moderate to abundant amount of pale cytoplasm. Few cells showed nuclear membrane indentation and occasional binucleate cells were also noted.

Further, the tumor was surgically removed, and histopathological examination of tumor showed partly autolyzed cellular tumor composed of cells mainly in sheets with focal papillary pattern [Figure 2d]. Cells showed mild-to-moderate pleomorphism with polygonal-to-oval cells, central to eccentrically placed nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Occasional mitotic figure (<2/10 high-power field) was noted along with foci of necrosis and part of brain parenchyma. A diagnosis of ACPP was made, consistent with the recurrence of tumor.

DISCUSSION

CPTs are relatively uncommon tumors of the CNS, constituting nearly 5% of all brain tumors occurring in childhood.[1234] Rarely, they occur as congenital or fetal tumors. These tumors originate from the choroid plexus epithelium in the ventricular system.[34]

CPTs are divided into two types: CPP (World Health Organization [WHO] Grade I) and CPC (WHO Grade III). An intermediate group lies between the two groups and is referred to as ACPP. CPPs are rare benign tumors and comprise 3%–5% of intracranial tumors in the pediatric population and 0.5% in the adults.[23456] They are found mostly in the lateral and fourth ventricles.

Headache is the most common initial presenting complaint. Regression of the attained milestones according to the age is seen in infants. The clinical progression is usually one of the gradual deteriorations.

On angiography, CPPs are hypervascular. CT is excellent at delineating calcifications and involvement of bony structures.[7] MRI is the preferable modality for the diagnosis of CPP. Complications such as spontaneous hemorrhage from the tumor, dissemination of tumor fragments, and hydrocephalus can occur in patients with CPP.

The presence of circulating malignant cells in CSF was described for the first time in 1904.[567] Tumor cells can be seen in CSF due to the leptomeningeal spread of the tumor. Very few cases of benign CPP showing metastasis as well as dissemination in the CSF have also been reported.[345678]

Metastasis of CPP is quite rare and only a few cases have been reported. Our cases are rare as there was shedding of tumor cells in CSF from CPP without any metastatic foci elsewhere on MRI brain.[8910] The plausible reason attributed is the friable nature of tumor, leading to the presence of cells in CSF due to contiguity of tumor to the CSF drainage pathway.[910] In our report, both children had CSF dissemination without any metastatic foci. Moreover, after extensive review of literature, the index case reports the youngest age group of a child with CPP.

CPP must be differentiated from a wide variety of lesions. Cells from normal choroid plexus may be indistinguishable from those seen in association with CPPs. Villous hypertrophy is a diffuse enlargement of the choroid plexus in both lateral ventricles with normal histological appearances. Cytologically, it may be confused for CPP.[234] However, the papillary clusters and single cells are usually much more numerous in association with a CPP than expected in a smear from villous hypertrophy of choroid plexus.

CPCs are associated with a dismal prognosis, especially if incompletely resected. It is important to distinguish CPC (WHO Grade III) from CPP (WHO Grade I). CPCs typically have a friable papillary or “cauliflower-like” appearance. Unlike CPC, CPPs are usually well delineated from the underlying brain parenchyma and lack necrosis. Distinction between these entities is imperative, but can be challenging, and it is generally based on the increased necrosis, mitotic activity, and growth pattern.[56789] Cytological features include various sized nuclei with a high nuclear cytoplasmic (N:C) ratio and scant cytoplasm. Nuclear indentations and lobulations are often striking. Single or multiple micronucleoli are frequent.

Although histological follow-up was not there in our case of 5-month-old child; cytological features favored a benign diagnosis over a malignant one with no marked pleomorphism, necrosis or high N:C ratio. Further, in our case radiology was very characteristic of CPT. Squash cytology of tumor shows preserved papillary architecture and cellular details. In our case, intact papillary fragment with vascular core was identified on CSF examination which is a much rare phenomenon.

In patients with recurrence, the presence of tumor cells in CSF can sometimes be a reactive hyperplasia owing to excessive production of CSF. However, in such cases, choroid plexus cells would be normal with no atypia, mitosis, and necrosis. Sometimes, the presence of tumor cells in such recurrent case can be progression of the disease or shedding of tumor cells in CSF. In such cases, there is mitosis, cellular pleomorphism, and necrosis.

CPCs typically stain positive for cytokeratin and display variable expression of Vimentin, S100, and transthyretin. Positivity for S100 and transthyretin is typically less than that seen in CPP. CPCs stain positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in approximately 20% of tumors, and they can express carcinoembryonic antigen.

Cells from a papillary ependymoma may be difficult to distinguish from those of a CPP. On cytology, papillary ependymoma consists of monomorphic cuboidal cells with micronuclei, stippled chromatin, ependymal rosettes, and perivascular pseudorosettes, in a glial stroma with radial fibrillary processes around blood vessels. Such glial background is not noted in CPP.[8910] The cell clusters of a papillary ependymoma may have a multilayered arrangement and frequently exhibit nuclear molding in contrast to those of a CPP. The presence of a rich fibrovascular stroma rather than glial-vascular stroma effectively rules out the diagnosis of a papillary ependymoma. Ependymomas often exhibit widespread GFAP positivity while CPP may show GFAP negativity or positivity in focal differentiated areas.

Papillary meningioma may also mimic CPP; however, on cytology, meningiomas produce hypercellular smears with sheets, papillae, and whorls of cells.[8] The cells range from polygonal to spindled, sparse or no mitosis, no necrosis, eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, and oval nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli. Intranuclear inclusions and grooving may also be seen. Meningiomas show positivity for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), Vimentin, and S100 whereas EMA is negative in CPP.

Intracranial primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) occur in children. While the cells in these tumors may be of a size similar to those seen in CPP, they typically reveal much higher N: C ratio, hyperchromatic nuclei with coarse chromatin. Nuclear molding is another striking feature of cell cluster originating from the PNETs. Metastatic tumors to the CNS may result in anaplastic cells in CSF. However, carcinoma metastasizing to the CNS or leptomeninges of a child would be extremely rare.[78910]

Despite certain classic features, it is not easy to differentiate these tumors on cytology alone. Correlation with radiological evaluation of location and size of lesion is the key differentiating feature in all these lesions. Pai et al. and Pant et al. had described the cytological features of CPTs along with various differential diagnosis which require a good clinicopathological correlation.[125]

The current treatment strategy consists of gross total surgical resection for both CPP and CPC, with appropriate use of adjuvant chemotherapy as clinically required. Gross total resection of the tumor can be obtained in 60%–90% of the cases.[6789]

Hydrocephalus which persists after removal of the tumor requires ventriculoperitoneal shunting. Radiation is advocated postoperatively to the tumor site, and to the spinal cord, if seeding is detected, and in recurrent tumors.[678910] Recurrence requires a second operation. In one of our cases, the 5-month-old child succumbed before surgical excision could be done. However, in the second case, even after recurrence of the tumor, the patient was doing well.

SUMMARY

To summarize, here we present the distinctive cytomorphological features of CPP shedding into the CSF in two patients: one in a 5-month-old child and other in a 12-year-old child. CSF cytology along with clinical and radiological correlation plays a crucial role in establishing an early diagnosis of the tumor. Cytomorphology also helps in excluding the other differentials, thereby leading to an immediate surgical intervention.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declared that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE. Each author has participated sufficiently in work and takes public responsibility for appropriateness of content of this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is a case report without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from institutional Review Board (IRB).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

1. ACPP - Atypical choroid plexus papilloma

2. CPP - Choroid plexus papilloma

3. CPC - Choroid plexus carcinoma

4. CPTs - Choroid plexus tumors

5. CSF - Cerebrospinal fluid

6. CT - Computed tomography

7. MRI - Magnetic resonance imaging.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Choroid plexus papilloma diagnosed by crush cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;25:165-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Choroid plexus papilloma with cytologic differential diagnosis – A case report. J Cytol. 2007;24:89-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Choroid plexus carcinoma presenting as an intraparenchymal mass. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:1040-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Choroid plexus carcinoma: Case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2012;7:71-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Choroid plexus tumors in childhood. Histopathologic study and clinico-pathological correlation. Childs Nerv Syst. 1991;7:437-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intraoperative consultation in the diagnosis of pediatric brain tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1653-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Papillary meningioma: A rare but distinct variant of malignant meningioma. Diagn Pathol. 2007;2:3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Choroid plexus tumors: An institutional series of 25 patients. Neurol India. 2010;58:429-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Choroid plexus papilloma in the posterior cranial fossa: MR, CT, and angiographic findings. Clin Imaging. 2001;25:154-62.

- [Google Scholar]