Translate this page into:

Gallbladder carcinoma: An attempt of WHO histological classification on fine needle aspiration material

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Carcinoma of the gallbladder (CaGB) is common in India and its prognosis depends primarily on the extent of the disease and histological type. We aim to study the role of guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) for diagnosis of CaGB and to evaluate the feasibility of applying world health organization (WHO) classification on fine needle aspiration (FNA) material to predict the outcome of the tumor.

Materials and Methods:

Retrospective cytomorphologic analysis was performed in all cases of CaGB diagnosed by ultrasound (US) guided FNAC over a period of 2 years. A specific subtype was assigned according to WHO classification based on characteristic cytologic features. These included papillary or acinar arrangement, intra and extracellular mucin, keratin, rosettes and columnar, signet ring, atypical squamous, small, clear, spindle and giant cells. Correlation with histopathology was performed when available.

Results:

A total of 541 aspirations with clinical or radiological suspicion of primary CaGB were studied. Of these, 54 aspirates were unsatisfactory. Fifty cases were negative for malignancy. Remaining 437 aspirates were positive for carcinoma. Histopathologic diagnosis was available in 32 cases. Adenocarcinoma was the most frequent diagnosis in 86.7% of cases. Mucinous, signet ring, adenosquamous, squamous, small cell, mixed adenoneuroendocrine and undifferentiated carcinoma including spindle and giant cell subtypes were diagnosed identifying specific features on FNAC. Correlation with histopathology was present in all, but one case giving rise to sensitivity of 96.8%. No post-FNA complications were recorded.

Conclusions:

US guided FNAC is a safe and effective method to diagnose CaGB. Although, rare, clinically and prognostically significant variants described in WHO classification can be detected on cytology.

Keywords

Cytomorphology

fine needle aspiration cytology

gallbladder carcinoma

ultrasound

world health organization classification

INTRODUCTION

Carcinoma of the gallbladder (CaGB) is the most frequent neoplasm of the biliary tract[12] and shows marked gender, ethnic and geographical variation in different parts of the world. In North India, it is one of the most common causes of cancer mortality.[34] The pre-operative diagnosis of CaGB is difficult owing to vague symptoms and the relative inaccessibility of the gallbladder to biopsy. Further, it clinically mimics benign gallbladder diseases and usually escapes detection until late in its course.[5] Early diagnosis with potential surgical intervention is not always possible.[6] Extensive resection is the best available therapeutic option for long-term survival, but the majority of patients present in an advanced stage and are inoperable.[7] Thus, there exists a strong rationale for the consideration of adjuvant therapy.[8] The prognosis for patients with CaGB depends primarily on the extent of disease and histological type.[1] Various tissue diagnostic procedures have been utilized to confirm the clinical and radiological diagnosis, including bile cytology, needle aspiration and biopsy of gallbladder.[9] Ultrasound (US) guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is a safe, quick and precise diagnostic procedure for early diagnosis and management of gallbladder cancer in developing countries.[10] Only few large studies on US/computed tomography guided percutaneous fine needle aspiration (FNA) of gallbladder are available in the literature until date. Moreover, the cytologic findings have not been illustrated in detail. In the present study, we describe the cytological findings in 437 cases of CaGB with histopathological correlation available in 32 cases over a period of 2 years. Further, subtyping of CaGB was carried out based on world health organization (WHO) classification on FNA material by analyzing the cytomorphological features.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All cases of US guided gallbladder aspirates performed from September 2010 to August 2012 were retrieved from the archives of Department of Pathology. All the cases had a clinical or radiological suspicion of gall bladder malignancy. May Grunwald Giemsa (MGG) and Papanicolaou (PAP) stained cytology smears were available in all cases. The smears were reviewed by four pathologists (RY, DJ, SRM and VKI) and the following parameters were evaluated:

-

Architectural pattern in the form of papillae, cohesive fragments, acini, sheets and singly scattered dyshesive cells

-

Presence and type of mucin whether intracellular or extracellular (mucin was identified as magenta or light green color on MGG or PAP stain respectively)

-

Specific features with the presence of atypical squamous cells, keratin, columnar tumor cells, signet ring cells, clear cells, giant cells, rosettes and spindle cells.

A diagnosis of signet ring, giant cell and spindle cell carcinoma was made when >90% of overall cellularity represented signet cells, giant cells and spindle cells respectively.

For analysis of differentiation of the tumor, a few key features were noted in addition to tumor cell architectural pattern, i.e., nuclear pleomorphism (mild, moderate, severe), nuclear membrane (smooth or irregular), nucleoli (absent, conspicuous, prominent), chromatin (fine or clumped), cytoplasm (scanty or abundant) and necrosis (present or absent). A note on type (acute or chronic) and severity (mild, moderate, severe) of inflammation was made.

On the basis of above mentioned cytomorphological features, the cases were classified according to WHO 2010 classification into adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS), mucinous adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, neuroendocrine tumor, small cell carcinoma, mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma NOS, spindle cell undifferentiated carcinoma and giant cell undifferentiated carcinoma. Papillary adenocarcinoma was diagnosed when papillary features were predominant.

Correlation with histopathology resection specimens was performed wherever available.

RESULTS

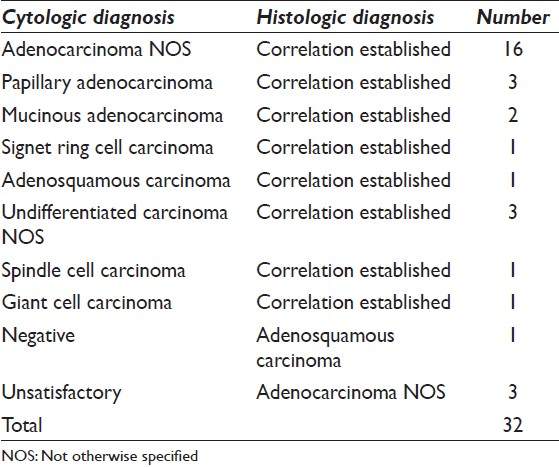

A total of 541 FNAs under US guidance were performed for the establishment of diagnosis of primary CaGB over a period of 24 months. In 32 cases, surgical resection was performed either due to low stage of cancer or where clinical suspicion of malignancy was strong in spite of cytology being negative or unsatisfactory. On cytology, 54 aspirates were unsatisfactory due to insufficient material for diagnosis giving rise to an inadequacy rate of 9.9%. Of these 54, three cases underwent resection and were found to be positive for malignancy. Fifty cases were negative for malignancy of which one had undergone resection due to strong clinical suspicion of malignancy. On correlation, this case was positive for adenocarcinoma. The negative cases were categorized into two groups: Normal epithelial elements and inflammatory. Twenty cases with normal hepatocytes and biliary epithelium constituted the first group. The inflammatory group consisted of 29 cases, which showed acute inflammatory exudate, foamy histiocytes, giant cells and/or granulomas. Diagnostic and morphologic correlation was established in remaining 28 cases resulting in a false negativity rate of 3.1% and sensitivity of 96.8% [Table 1]. Four hundred thirty-seven cases were positive for malignancy. There were 292 women and 145 men (Female:male = 2:1). Age ranged from 24 years to 85 years with a mean of 45 years. The signs and symptoms were variable and included abdominal pain, jaundice, pruritus, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss and abdominal mass.

The detailed morphologic descriptions of all positive cases (437) with histopathology findings of 32 cases are given below and in Table 2.

Adenocarcinoma

Of 437 aspirates, 379 (86.7%) were characterized as adenocarcinomas including 35 papillary, 24 mucinous and 2 cases of signet ring cell carcinoma. The rest of the adenocarcinomas (318/437, 72.8%) were categorized into NOS subgroup. Biliary, gastric and intestinal subtypes were not accurately recognized on cytology; however, presence of columnar type tumor cells was correlated with intestinal morphology on histology in 1 case. We did not find clear cell and hepatoid subtypes.

Adenocarcinoma NOS category was confirmed as adenocarcinoma on histology in 16 cases including predominantly biliary subtype.

Papillary adenocarcinoma

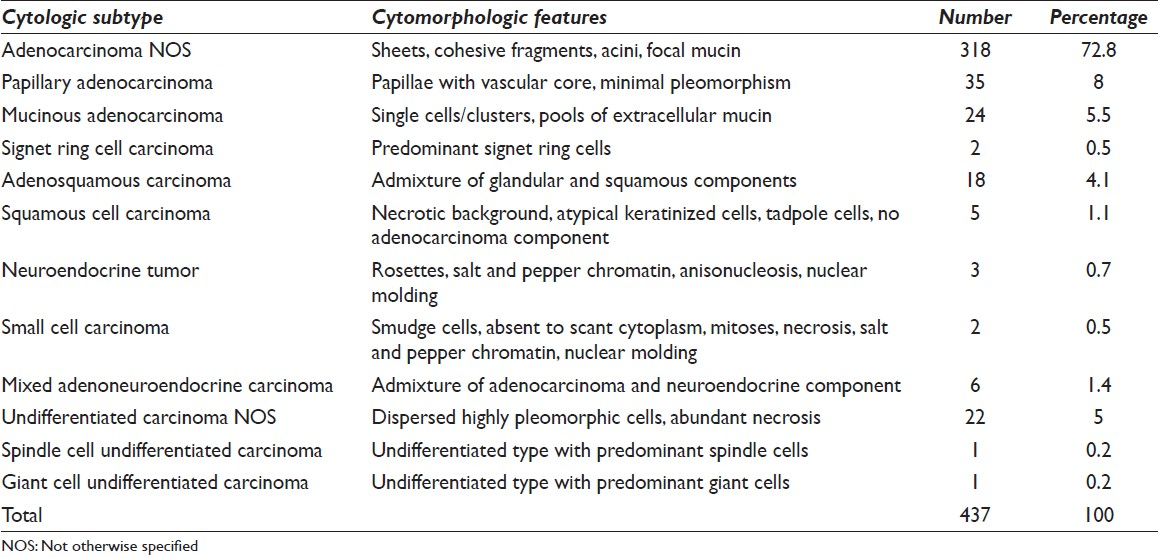

It comprised 8% (35/437) of all carcinomas. Morphologically, tumors showed predominantly true papillary fragments [Figure 1a]. The cells showed minimal nuclear pleomorphism. Most of the (24/35) aspirates corresponded to well-differentiated category owing to maintained tumor architecture and less cytological atypia.

- (a) Papillary fragments of tumor cells showing minimal cellular and nuclear pleomorphism, papanicolaou (Pap ×100), (b) intestinal type papillary adenocarcinoma showing true papillae with central fibrovascular cores lined by tall columnar cells and rare goblet cells, H and E, ×100, (c) papillae lined by tall columnar cells along with abundant mucus cells in a case of gastric type of papillary adenocarcinoma, H and E, ×200, (d) columnar tumor cells on cytology, Pap ×400

Three cases (3/35) had corresponding histology. Histologic examination showed well- differentiated papillary adenocarcinoma including one case each of intestinal, gastric foveolar and biliary type. Intestinal type was determined by the presence of tall columnar cells with rare goblet cells [Figure 1b]. Gastric foveolar subtype was identified by the presence of gastric mucus cells [Figure 1c].

On correlation, it was not possible to make a diagnosis of gastric or biliary subtypes on cytology, whereas the presence of tall columnar tumor cells on aspirates supported the diagnosis of intestinal subtype [Figure 1d].

Mucinous adenocarcinoma

These constituted 5.5% (24/437) of all adenocarcinomas. They showed either single cells or clusters of tumor cells floating in abundant extracellular pools of mucin [Figure 2a]. A few cases showed focal intracellular mucin. All of them represented moderately differentiated pattern because of frequent dyscohesion and noticeable nuclear pleomorphism.

- (a) Tumor cells floating in abundant extracellular mucin, May Grunwald Giemsa (MGG) ×100, (b) mucinous carcinoma showing clusters of tumor cells lying in pools of mucin, H and E, ×100, (c) singly lying tumor cells with abundant intracellular mucin pushing the nucleus to the periphery signifying signet ring appearance, papanicolaou ×400, (d) tumor cells showing moderate nuclear pleomorphism and arranged in cohesive fragments, MGG ×200

Two (2/24) cases had corresponding histopathology in which more than 50% of the tumor exhibited extracellular mucin with floating malignant cells or glands [Figure 2b].

Signet ring cell carcinoma

This subtype comprised of 0.5% (2/437) of all carcinomas. Predominantly intracellular mucin containing cells with nuclei pushed to periphery representing signet ring cells were seen [Figure 2c]. Both cases showed moderate tumor differentiation.

Corresponding histology was available in one of the cases. Signet ring cell carcinoma was typified by the presence of characteristic signet cells with intracellular mucin.

The adenocarcinoma cases (379) were also categorized into well, moderate and poorly differentiated subtypes, which constituted 6.3% (24/379), 84.5% (320/379) and 9.2% (35/379) of all adenocarcinomas. In the well-differentiated subtype, cells were mainly arranged in well-formed papillae. The cells showed low nuclear/cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio, round to oval nuclei with mild anisonucleosis, small nucleoli and fine chromatin [Figure 1a]. Focal intracellular mucin was also noted. Cells in the moderately differentiated subgroup were arranged in cohesive fragments, acini and sheets and scattered singly. The cells showed moderate amount of cytoplasm, centrally placed nuclei with moderate pleomorphism, vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli [Figure 2d]. Focal tumor necrosis, few tumor giant cells and extra/intracellular mucin were also seen. Poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas showed predominantly dyscohesive tumor cells along with abundant necrosis, inflammatory exudate and many tumor giant cells. The cells showed high N/C ratio, moderate to marked nuclear pleomorphism, multiple prominent nucleoli and stippled chromatin. Few fragments, acini and intracellular mucin were the helpful features to diagnose adenocarcinoma in some of the cases (9/35). In 24 cases, no differentiation was recognized hence labeled as poorly differentiated carcinomas.

Well-differentiated category encompassed all papillary adenocarcinoma cases, whereas poorly differentiated carcinomas represented undifferentiated subtype of WHO classification. Moderately and poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas were either adenocarcinoma NOS or specific subtypes based on defined features.

Adenosquamous and squamous cell carcinoma

Adenosquamous subtype was present in 4.1% (18/437) cases. Combination of features of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma were identified. One case was confirmed on histopathological examination.

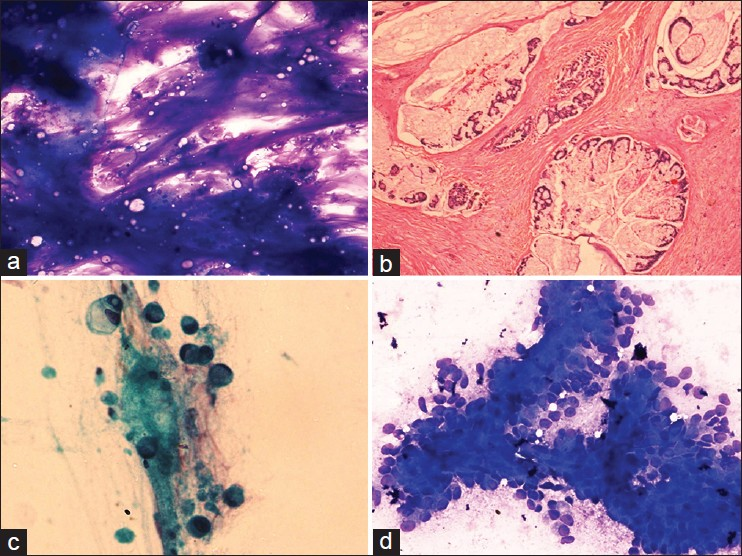

Pure squamous cell carcinoma constituted 1.1% (5/437) of cases. These cases showed predominantly scattered tumor cells with focal to abundant necrosis. The cells showed keratinization, angulated borders, pyknotic hyperchromatic nuclei and dense cytoplasm [Figure 3a]. No adenocarcinoma component was seen. Corresponding histopathology was not available in these two cases however.

- (a) Squamous differentiation is typified by atypical keratinized cells with dense cytoplasm and pyknotic nuclei in a necrotic background, Papanicolaou (Pap ×400), (b) Tumor cells showing dramatic anisonucleosis and nuclear molding with rosettes representing neuroendocrine differentiation, May Grunwald Giemsa ×200, (c) Tumor cells show hyperchromatic nuclei with salt and pepper nuclear chromatin and molding in a case of small cell carcinoma, Pap ×400, (d) Large markedly pleomorphic tumor giant cells exhibit neutrophilic phagocytosis, Pap ×400

Neuroendocrine tumor

Three (0.7%) cases were classified into neuroendocrine subgroup. Cells in these cases were arranged in small groups and rosettes and consisted of medium sized round to oval nuclei with a small amount of cytoplasm. The nuclei showed salt and pepper chromatin, small nucleoli, focal dramatic anisonucleosis and nuclear molding [Figure 3b].

Small cell carcinoma

Two (0.5%) cases showed features of small cell carcinoma. The cells were predominantly singly dispersed and contained scant to absent cytoplasm. Nuclei showed moderate anisonucleosis, salt and pepper chromatin, nuclear molding and absence of nucleoli [Figure 3c]. Smudge cells, necrosis and mitoses were also seen.

When a combination of features of conventional adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumor were present, cases were classified into mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma group. This group comprised of 6 (1.4%) cases.

Undifferentiated carcinoma

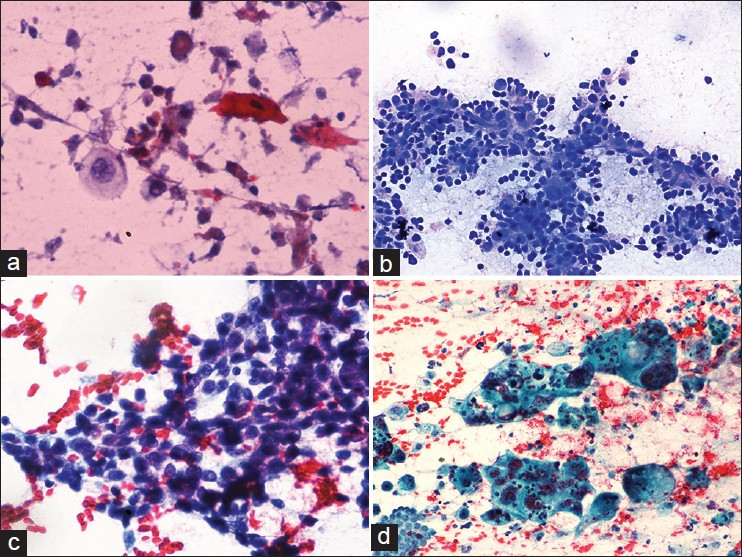

This subgroup consisted of 24 (5.5%) cases. These cases showed predominantly dispersed population of large tumor cells with abundant necrosis and numerous tumor giant cells. The cells displayed marked nuclear pleomorphism, coarsely clumped chromatin and macronucleoli. No features suggestive of adenocarcinoma or squamous or neuroendocrine differentiation were found. One of the cases showed predominantly singly scattered highly pleomorphic spindle shaped cells with coarsely clumped chromatin. Numerous bizarre cells with abundant necrosis were identified. This case was labeled as spindle cell subtype. Another case showed a preponderance of binucleate, trinucleate and multinucleated tumor giant cells along with necrosis and mitoses. This case was categorized into giant cell subtype of undifferentiated carcinoma [Figure 3d]. Spindle cell and giant cell subtypes showed sarcomatoid morphology and giant cell phenotype on corresponding histology [Figure 4a and b]. In addition, three other cases of undifferentiated carcinoma NOS type remained undifferentiated on resection specimens.

- (a) Undifferentiated carcinoma with predominant spindle shaped tumor cells showing marked nuclear pleomorphism and frequent mitoses, H and E, ×200, (b) Giant cell rich type of undifferentiated carcinoma showing numerous bizarre tumor giant cells, H and E, ×400

No FNAC related complications were recorded in any of these patients.

DISCUSSION

CaGB predominates in the female population with variable prevalence in different parts of the world.[11] In the USA, its frequency is 1.43/100,000 persons, whereas in India, it shows marked regional variation. In North India (Delhi), the incidence is 21.5/100,000 females and the female to male incidence ratio is around three.[111213] Earlier studies from India reported the age of peak incidence to be in the 7th decade of life.[5] However, in the present study mean age of the presentation was 45 years. Implicated etiologic factors include cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, racial and ethnic factors, blood groups, carcinogens, lipid peroxidation products, benign tumors and secondary bile acids.[14.15.16] Clinical presentation of gallbladder malignancy and benign gallbladder disease is almost similar and most of the times it is masked by chronic cholecystitis.[517] The rising incidence and high mortality rate of biliary tract cancers demands urgency to search for early diagnosis.

Establishing diagnosis in early stage of the disease is difficult.[5] FNAC is helpful in pre-operative decisions regarding the type and extent of surgical procedure and subsequent treatment, especially in cases considered to be inoperable due to extensive invasion by the tumor. It obviates the need of laparotomy in advanced cases and in patients who are poor surgical candidates.[18] Role of FNAC in diagnosis of CaGB has been documented in the literature largely in late 80's and 90's. FNAC under image guidance has been considered superior in terms of diagnostic yield and sample adequacy result in to higher sensitivity.[9]

FNAC has been found to be a useful modality for the diagnosis of CaGB with sensitivity reported from 74% to 100% and inadequacy rate of 4-29%.[19] False negativity is a well-known limitation of FNAC, which could be attributed to incorrect sampling, necrosis or fibrosis. In gallbladder malignancies false negativity of 11-41% has been documented.[18]

Rare complications reported in older studies with procedures involving gallbladder puncture (bile aspiration) including severe vasovagal reaction, hemorrhage, hemobilia, hypotension and bacteremia were not observed in any of our cases.[20] Moreover, FNA of the gallbladder has not been reported to be associated with any of the above mentioned complications until date.[21] The present series is the largest series of CaGB diagnosed by US guided FNAC. Guided FNAC can provide an accurate diagnosis from easily obtained adequate samples with sensitivity of 96.8%, inadequacy of 9.9% and false negative rate of 3.1%.

Uncommon variants of poor prognosis, classified by WHO, such as mucinous carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma can be diagnosed on cytology material.

As far as predictors of outcome in CaGB are concerned, histologic type, grade and stage of the disease are considered useful parameters in various series.[122] Thus, subtype characterization and classification according to grade of the tumor are essential on cytology for guiding the clinician in patient management and prognostication.

WHO (2010) classifies CaGB in to various morphologic subtypes with their associated prognostic relevance.[1] It separates conventional adenocarcinoma into intestinal, gastric foveolar and biliary subtypes in addition to prognostically significant mucinous, signet cell, clear cell and hepatoid variants. Papillary adenocarcinoma is not included; however, it has been considered a good prognostic subtype as described previously by Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP).[23]

We also found largely well-differentiated morphology in papillary adenocarcinoma in the present series. The intestinal type adenocarcinoma resembles intestinal epithelium with or without goblet cells. An intestinal type of adenocarcinoma, indicated by the presence of tall columnar cells on cytology, may be recognized. Gastric and biliary are other subtypes; however, these were not identified separately on cytology. Instead our approach to categorize papillary and non-papillary adenocarcinomas was feasible and this might have prognostic relevance as suggested by AFIP.

Mucinous adenocarcinoma is characterized by the presence of more than 50% extracellular mucin.[1] It is an uncommon variant of CaGB and is noted in the literature mostly as case reports or small series of cases. Cytologically mucinous carcinoma is difficult to define based on >50% criterion of mucin; however, when mucin is in abundance and more than cells or glands in smears it should be classified as mucinous variant. There were two cases where excessive mucin was correlated with mucinous carcinoma on histology. It is important to identify mucinous variant as it possesses more aggressive behavior than ordinary gallbladder carcinomas.[24]

Squamous differentiation is uncommon in the gallbladder carcinoma.[12] Squamous and adenosquamous carcinomas constituted 10% and 12.5% of total gallbladder malignancies respectively.[925] However, in a recent study of 606 cases by Roa et al., squamous differentiation was detected in 7% of the cases. Pure squamous cell carcinomas constituted only 1% of the cases.[12] In our study, squamous and adenosquamous carcinomas together formed 5% of malignancies. Their prognosis has been reported to be dismal as compared with gallbladder adenocarcinomas.[12]

The diagnosis of pure squamous cell carcinoma was established when there was no adenocarcinoma component in all the smears examined. Atypical squamous cells were recognized in the background of necrosis and inflammatory exudate. However, there was no histologic correlation in these cases to exclude the possibility of minor adenocarcinoma component and thus the diagnosis of adenosquamous carcinoma.

The differentiation of neuroendocrine tumors from small cell carcinoma on cytology was based upon the absence of mitosis and necrosis and presence of well-formed rosettes. Small cell carcinoma displayed typical features as at other sites in the form of hyperchromatic nuclei with molding. The prognosis of small cell CaGB remains poor with the majority of patients presenting with metastases.[2126]

Comparative assessment of well, moderate and poorly differentiated tumors with WHO subtypes showed concordance. All well-differentiated carcinomas were papillary carcinomas. It was at times difficult to exclude reactive hyperplasia of ductal epithelium in well-differentiated papillary adenocarcinoma; however, nuclear overlapping and loss of polarity in addition to clinical and radiological features were helpful in establishing the diagnosis of carcinoma. If there was no morphologic clue to suggest adenocarcinoma, cases were designated poorly differentiated carcinoma and later subtyped as undifferentiated carcinomas.

To conclude, the present study is the largest series evaluating the role of US guided FNAC in diagnosis of CaGB. Cytology plays a significant role in the pre-therapeutic workup of gallbladder carcinomas. In addition to early confirmation and pre-operative diagnosis of malignancy, it allows for morphologic evaluation and appropriate subtype characterization according to WHO classification, which is necessary for prognostication of the disease.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

None of the authors have any conflict of interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that they qualify for authorship as defined by the ICMJE. All the authors are responsible for the conception of this study, have participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) (or its equivalent) of all the institutions associated with this study as applicable. Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of Cyto Journal Publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind mode (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2013/10/1/12/113627

REFERENCES

- Carcinoma of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System (4th ed). WHO Press: Geneva; 2010. p. :263-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology and molecular pathology of gallbladder cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:349-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gallbladder cancer (GBC): 10-year experience at memorial sloan-kettering cancer centre (MSKCC) J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:485-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Carcinoma of the gallbladder: A retrospective review of 99 cases. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1145-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive review of the diagnosis and treatment of biliary tract cancer 2012. Part I: Diagnosis-clinical staging and pathology. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:332-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Jaundice predicts advanced disease and early mortality in patients with gallbladder cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:310-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy useful for gallbladder carcinoma.A phase III multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial in patients with resected pancreaticobiliary carcinoma? Cancer. 2002;95:1685-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology diagnosis of gallbladder lesions: A study of 82 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 1998;18:258-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of abdominal masses. JK Sci. 2006;8:200-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gallbladder cancer worldwide: Geographical distribution and risk factors. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1591-602.

- [Google Scholar]

- Squamous cell and adenosquamous carcinomas of the gallbladder: Clinicopathological analysis of 34 cases identified in 606 carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1069-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Carcinomas of the pancreas, gallbladder, extrahepatic bile ducts, and ampulla of vater share a field for carcinogenesis: A population-based study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:67-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Environmental pollutants in gallbladder carcinogenesis. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:640-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidental gallbladder carcinoma: Value of routine histological examination of cholecystectomy specimens. Nepal Med Coll J. 2010;12:90-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology of malignant gallbladder masses. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:1654-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of gall bladder malignancies. Acta Radiol. 1999;40:436-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic and therapeutic interventional gallbladder procedures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:913-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration of primary gallbladder carcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1996;15:151-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Carcinoma of the gallbladder.Histologic types, stage of disease, grade, and survival rates. Cancer. 1992;70:1493-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tumors of the Gallbladder and Extrahepatic Bile Ducts. In: Atlas of Tumor Pathology. 2nd Series. Fascicle 22. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1986. p. :108.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mucinous carcinomas of the gallbladder: Clinicopathologic analysis of 15 cases identified in 606 carcinomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1347-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathology of malignant neoplasms of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. In: Wanebo HJ, ed. Hepatic and Biliary Cancer. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1987. p. :281-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Small cell carcinoma of the gallbladder: A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular pathology study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:595-601.

- [Google Scholar]