Translate this page into:

The Bethesda System thyroid diagnostic categories in the African-American population in conjunction with surgical pathology follow-up

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

It has been reported that African-Americans (AA) have a higher prevalence of overall malignancy compared to Caucasians, in the United States, yet the incidence of thyroid malignancy is half. The aim of this study is to assess the rate of malignant versus benign thyroid disease in AA from an urban-based hospital with an academic setting. Our study analyzed the AA population with respect to fine needle aspiration (FNA) of thyroid lesions, in correlation with final surgical pathology. This is the first study of its kind to our knowledge.

Design:

We retrospectively reviewed thyroid FNA cytology between January 2005 and February 2011. Consecutive FNA specimens with corresponding follow-up surgical pathology were included. The patients were categorized as African- American (AA) and Non-African-American (NAA), which included Caucasians (C), Hispanics (H), and Others (O). The FNA results were classified using the latest edition of The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology (TBS-Thy) and the follow-up surgical pathology was used for the final categorization.

Results:

We studied 258 cases: 144 AA (56%) and 114 NAA [43 C (17%), 3 H (1%), and 68 O (28%)]. The average age for AA was 51 years (range 20 – 88) and for NAA was 53 years (range 25 – 86). There were more females than males in the AA versus the NAA group (85 vs. 75%). The incidence of thyroid lesions in the FNA specimens was similar between these two populations. The distribution of benign versus malignant diagnosis on follow-up surgical pathology was examined across TBS-Thy class.

Conclusion:

Our data suggest that distribution of benign versus malignant lesions in the thyroid FNA of AA versus NAA, with follow-up surgical pathology, is comparable for TBS-Thy classes, non-diagnostic (I), benign (II), suspicious for malignancy (V), and malignant (VI) in AA versus NAA.

Keywords

African–American

FNA

thyroid

INTRODUCTION

African–Americans (AA) have a higher incidence of malignancies than Non-African–Americans (NAA). However, a recent report indicates that the incidence of thyroid cancer in AA is half that of Caucasians.[1] The reason for this remains unclear.

It has been well documented that the rate of thyroid disease/malignancies in the general population has increased substantially over the past few decades. According to the National Cancer Institute's (NCI) Surveillance Epidemiology and End Result (SEER) database, the incidence of thyroid malignancies in the United States, from 1975 to 2007, has increased. In Caucasians, the incidence of thyroid cancer has risen slightly more than in the general population (2.73 fold vs. 2.45 fold), while the incidence in AA has increased as well, but at a rate less than that for the general population (2.35 fold vs. 2.45 fold) with the caveat that the incidence rate in AA was lower and has remained lower than that in the general population and Caucasians.[2] According to the 2008 publication by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, the incidence and mortality of thyroid cancer are 1.4 and 1.0 in Africa, 9.9 and 0.3 in the United States, 2.2 and 0.6 in the less developed countries, and 6.1 and 0.4 in more developed countries.[3]

The introduction of thyroid FNA in 1952, the acceptance of thyroid FNA as a screening tool in the 1970s, and ultrasound detection of incidentalomas, can in part account for the rise in the general population coinciding with the increase in the use of thyroid FNA as a screening tool over more invasive procedures, leading to an increased number of resections of clinically significant lesions.[4] The reasons for the difference in incidence rates for AA versus the general population, however, have yet to be elucidated. To date, a few studies exist that address this subject. In 1977, Chung et al. and Mosley et al. published studies looking at thyroid disease/carcinoma in Black patients.[56] In their studies, they looked at the surgical pathology reports of thyroidectomies in AA from 1950 to 1975.[56] The studies were done during a time when thyroid FNA was not widely adopted as a screening tool. Morris et al. specifically looked at the AA population using the NCI's SEER database, coming up with three hypotheses to address the difference in prevalence of thyroid disease/malignancies, which included the following: under diagnosis/detection, lower incidence, and/or less aggressive disease.[1] Brown et al. recently published an article specifically looking at the incidence of thyroid malignancies in AA versus Caucasians, which examined the rates with equal access to healthcare.[7]

All the aforementioned studies were done using the data from surgical pathology studies. In terms of the incidence of thyroid lesions in AA, using FNA, no studies were found. To evaluate thyroid FNAs among the ethnically diverse Detroit metropolitan population, we previously reported a study looking at the FNA results within AA, the first study of its kind.[8] Our current study was performed to evaluate thyroid FNAs among the ethnically diverse Detroit metropolitan population in conjunction with surgical pathology follow-up. Given our location in the Detroit metropolitan area, a large number of AA patients are seen in the thyroid clinic, which provides us with a great opportunity to address the question of, whether or not a difference exists in the rate of thyroid malignancies in AA versus NAA.

DESIGN

We retrospectively reviewed the FNA cytopathology reports and the corresponding surgical pathology reports between January 2005 and February 2011, after obtaining IRB approval. Overall, the number of thyroid FNA cases during the study period was 2791 and corresponded to 2217 patients. A majority of the thyroid FNAs were performed by the Department of Endocrinology at our institution, which has a very active weekly ultrasound-guided thyroid FNA clinic, where the Department of Cytopathology served a vital role in providing on-site adequacy evaluation. The attending cytopathologist, fellow/resident and a cytotechnologist were on site, with all the tools necessary to provide this service. Typically, the endocrinologist/endocrinology fellow performed three to four passes with two smears made from each pass, depending on the lesion size and accessibility. One air-dried slide from each needle pass was stained with a Diff-QuikR stain for on-site adequacy evaluation and the corresponding alcohol-fixed slide was submitted for Papanicoloau staining. A cell block was prepared, made from the needle rinse during on-site evaluation. Six cytopathologists signed out the cases during the study period.

The FNA results from 276 patients, with corresponding surgical pathology, were identified, with data from 258 patients meeting our inclusion criteria. Cases where the racial identity was not known were excluded, as were cases involving metastatic cancers from other sites. The 258 patients were associated with 311 FNA specimens and 265 surgical pathology specimens. As many patients had multiple FNA procedures, with some having multiple follow-up surgical pathology specimens as well, only the antecedent FNA results with respect to one follow-up surgical pathology report corresponding to the site of FNA, were included. Our institution is affiliated with the Karmanos Cancer Institute, which specializes in the treatment of a variety of cancers, including head and neck cancer, and is a major specialty treatment center of its kind in the area. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, subsequent thyroid surgical resections were performed at the author's institution.

The patients were sub-categorized as African–Americans (AA), Caucasians (C), Hispanics (H), and Others (O), based on demographic data obtained from the online medical records. The ethnic classification in the demographic data was obtained as a result of the ethnic group assignment, with the patients themselves checking off the appropriate classification on the forms. This was subsequently reflected in the patient charts. The C, H, and O were grouped together under the heading Non-African-American (NAA). The FNA results were subcategorized using the latest edition of The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology (TBS-Thy).[9–11] The categories included non-diagnostic (class I), benign (class II), follicular lesion of undetermined significance (FLUS)/atypia of undetermined significance (class III), follicular neoplasm/suspicious for follicular neoplasm (class IV), suspicious for malignancy (class V), and malignant (class VI). The surgical pathology results were used for final categorization. All malignant surgical pathology results, regardless of size, were analyzed. Chi-squared analyses were conducted to examine the association between nominal variables, where the sample size was sufficient to allow for such an application. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 (Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Of the 258 patient material reviewed, 144 (56%) were AA and 114 (44%) were NAA [43 (17%) C, 3 (1%) H, 68 (26%) O]. The average age for AA was 51 years (range 20 – 88) and for NAA was 53 years (range 25 – 86). Similar to the overall population, there were more females than males noted in the AA versus the NAA group (85 and 75%, respectively).

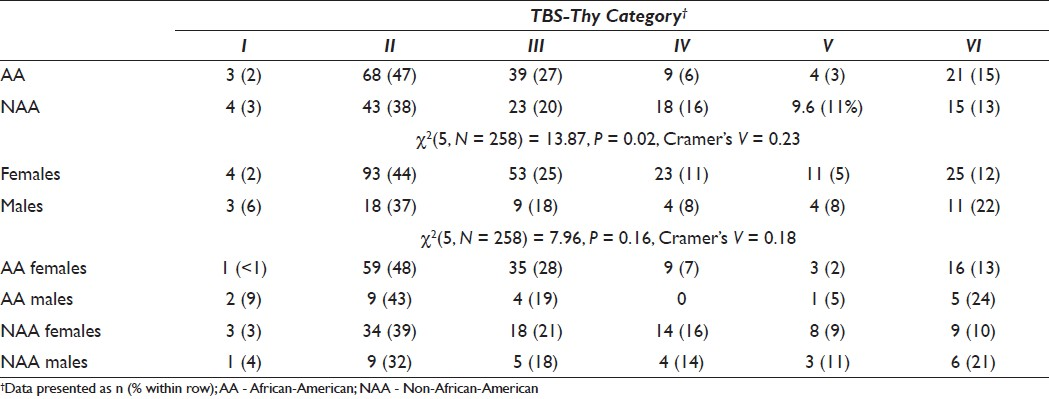

Ethnicity and gender across TBS-Thy category

Examining ethnicity groups, irrespective of gender, the proportion of thyroid lesions in the FNA specimens across TBS-Thy category was significantly different between AA and NAA, χ2 (5, N = 258) = 13.87, P = 0.02, Cramer's V = 0.23 [Table 1, top table]. The most marked differences between the ethnicity groups were observed for class II (AA = 47%; NAA = 38%) and class IV (AA = 6%; NAA = 16%). The majority of thyroid lesions in the FNA specimens, for both ethnicity groups, were assigned to TBS-Thy classes II and III. Examining the gender groups, irrespective of ethnicity, the proportion of thyroid lesions in the FNA specimens across TBS-Thy categories was not significantly different between females and males, χ2 (5, N = 258) = 7.96, P = 0.16, Cramer's V = 0.18 [Table 1, middle table]. Descriptively, the most marked difference between the gender groups was observed for class II (females = 44%; males = 37%) and class VI (females = 12%; males = 22%). The expected cell frequencies were too small to allow for chi-squared analyses of ethnicity X gender sub-groups [Table 1, bottom table].

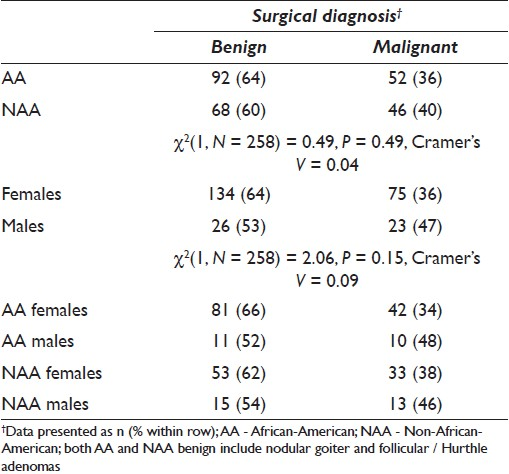

Ethnicity and gender across surgical diagnosis

On examining the ethnicity groups, irrespective of gender, there were no significant differences between AA and NAA in the proportion of thyroid lesions classified between the surgical outcomes, χ2 (1, N = 258) = 0.49, P = 0.49, Cramer's V = 0.04 [Table 2, top table]. On examining the gender groups irrespective of ethnicity, there were no significant differences between females and males in the proportion of thyroid lesions classified between surgical outcomes, χ2 (1, N = 258) = 2.06, P = 0.15, Cramer's V = 0.09 [Table 2, middle table].

Regarding the gender X ethnicity sub-groups, there were no significant differences between females and males in the proportion of thyroid lesions classified between surgical outcomes for AA, χ2 (1, N = 144) = 1.41, P = 0.24, Cramer's V = 0.10, or for NAA, χ2 (1, N = 114) = 0.57, P = 0.45, Cramer's V = 0.07 [Table 2, bottom table]. For both AA and NAA, however, a greater proportion of lesions were classified as malignant in males, than in females. Finally, there were no significant differences between AA and NAA in the proportion of thyroid lesions classified between surgical outcomes for females, χ2 (1, N = 209) = 0.39, P= 0.53, Cramer's V = 0.04, or for males, χ2 (1, N = 49) = 0.01, p = 0.93, Cramer's V = 0.01 [Table 2, bottom table].

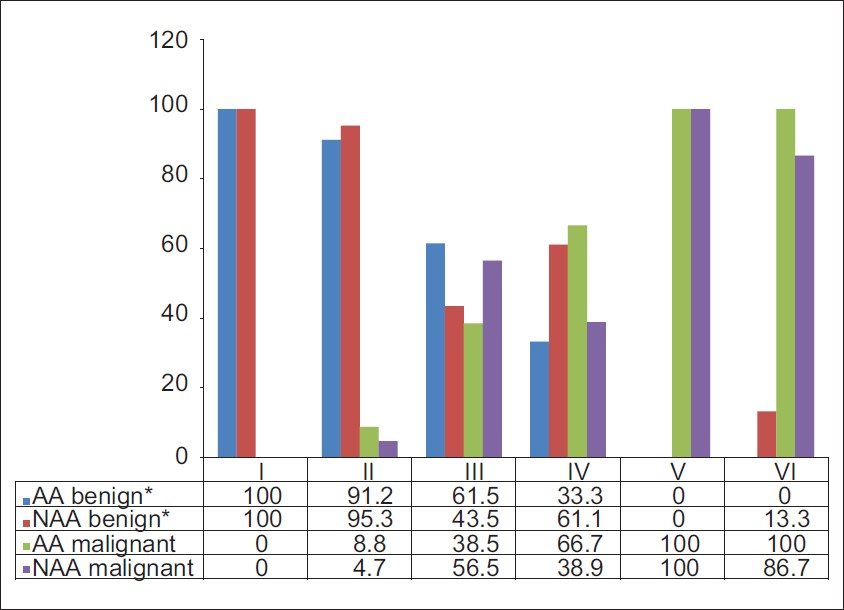

Ethnicity and surgical pathology diagnosis across TBS-Thy category

The distribution of benign versus malignant diagnoses on follow-up surgical pathology was examined across TBS-Thy class. The spectrum of lesions diagnosed was comparable between the two groups, for all classes, with the exception of classes III and IV, as summarized in Figure 1. Although lesions as small as 3 mm could be visualized by ultrasound, lesions less than 5 mm were not targeted by the endocrinologists in the thyroid clinic. Benign FNA results with corresponding microcarcinomas less than 5 mm, noted in the surgical specimens, corresponding to the initial area of FNA were counted as benign under TBS-Thy category II lesions, in Figure 1. Four such cases in AA and two cases in NAA fell into this category. Reclassifying these cases would not have significantly affected the results.

- Percent of benign and malignant cases by ethnicity and TBS-Thy category. *Benign includes non-neoplastic lesions and adenomas

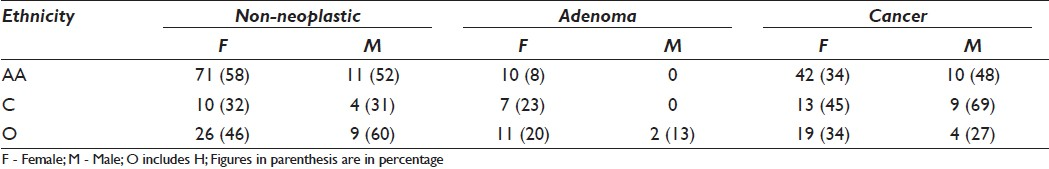

Ethnicity and distribution of surgical pathology diagnosis by biological behavior, tumor size, and histological type

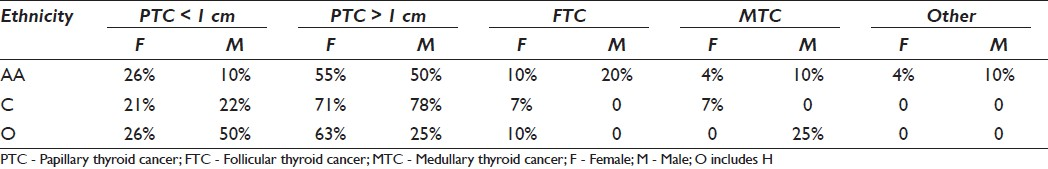

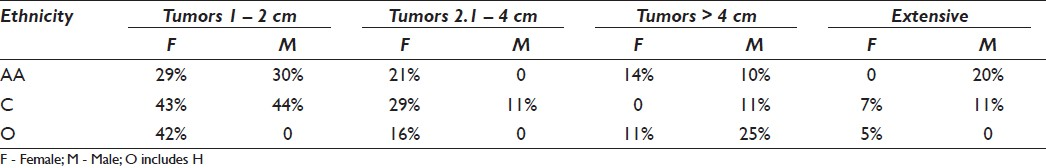

The rates of non-neoplastic lesions, adenomas, and cancer in AA and NAA men and women are shown in Table 3. AA women were noted to have a higher rate of benign non-neoplastic lesions, lower rate of benign neoplastic lesions, and a lower rate of malignancies, compared to NAA women. Similar findings were observed in AA men versus NAA men. AA women were also observed to have a lower rate of malignancies compared to AA men. Breaking the NAA into C and O, however, revealed a lower rate of cancer in AA versus C. AA were noted to have a lower rate of clinically significant papillary thyroid cancer [Table 4]. AA males were observed to have a higher rate of follicular thyroid cancer, a higher rate of extensive disease, and a lower rate of microtumors [Tables 4 and 5].

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to evaluate if there was any difference in the rate of thyroid malignancies based on the thyroid FNA data in AA versus NAA. Based on our previous study,[8] the distribution pattern of thyroid FNA TBS-Thy diagnostic categories and follow-up results for AA and the general population are similar for most of the categories. The preliminary results from our current study suggest that although AA have a lower rate of thyroid malignancies, they are more likely to suffer from a more aggressive disease with/without higher stage. The reasons for this could not be elucidated in this study. Potential causes included delay in diagnosis (which would address both under detection and/or advanced stage at presentation), environmental factors, and intrinsic factors. This finding differed from the 2007 SEER database finding, where it was reported that AA were less like to suffer from more aggressive disease.[2]

The rate of thyroid malignancies in AA found in our current study (36%) was higher than those previously reported by Chung et al. (4.6%).[5] The time frame of their study (January 1, 1950 to December 31, 1975), however, was before the widespread application of FNA as an evaluation tool. As a result, it was likely that many more cases of clinically insignificant lesions could have been resected, than what would have been done based on radiographic and clinical impression alone. FNA would have curtailed the avoidable resections, and streamlined the resection of more clinically significant lesions.

Brown et al.[7] reported that the rates of thyroid malignancies in surgical pathology specimens were similar when both groups had equal access to healthcare. This contrasts with what was found by Morris et al.[1] who reported some disparities, noting correlation in thyroid cancer both in respect to uninsured versus insured and lower median income versus higher incomes. Morris et al.[1] found that the gap in incidence of thyroid cancer was too large to be accounted for by the disparities they found alone, similar to what was found by Yu et al.[12] in their examination of the 13-year SEER data. These areas could neither be addressed by our studies nor by Brown et al.[7]

Furthermore, although the rates of well-differentiated thyroid malignancies in our study were similar for AA and C, AA were noted to be diagnosed with more follicular carcinoma and less papillary carcinoma than C, and were more likely to have larger tumors at initial diagnosis as well [Tables 4 and 5]. This trend is similar to that reported in the latest SEER report.[2]

All of the aforementioned studies addressing thyroid disease in AA[125712] were generated using surgical pathology data only. For the first time, we demonstrated that the distribution of benign versus malignant lesions in thyroid FNA, with surgical pathology follow-up, was similar for most of TBS-Thy classes in both groups (AA versus NAA). However, there was an observed difference in classes III and IV, with the rate of malignancy for AA and NAA being 38.5 and 56.5%, respectively, for class III and 67 and 39%, respectively, for class IV [Figure 1].

We have observed a higher number of cases in class III (27.1 and 20.2% for AA and NAA, respectively) than suggested in the Bethesda System (7%). Our institution is not unique in this regard as the percentage of class III lesions vary from institution to institution from low [3.2 and 3.4% by Yang et al. and Jo et al., respectively[1314] to high Ohori et al., 20.5%.[15] Several criteria are outlined in TBS-Thy for class III, including but not limited to, hypocellularity and poor preservation/poorly visualized area.[9] As such, there exists the possibility of over utilizing this category. The difference in the number of class III lesions between institutions may, in part, be due to interobserver variation between pathologists as well as how the lesions are classified as class III from institution to institution. Prior to the Bethesda System for thyroid reporting, our institution used the diagnostic terms ‘cellular follicular lesion’ and ‘follicular lesion with atypia’ to refer to class III. All our FNA reports include microscopic descriptions as well, which have been compared with the criteria listed in the Bethesda System to re-classify the lesions predating the Bethesda System.[16] In our study, the rates of malignancy for this category on follow-up were 38 and 56%, for AA and NAA, respectively, whereas, the malignancy rate in the current edition of The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology for class III is estimated to be 5 – 10% and up to 20 – 25% in cases with surgical follow-up.[9] Our rate of malignancy for this category, however, is even higher than what has been reported in the literature (17% by Jo et al.,[14] 17.1% by Ohori et al.,[15] 13.5 / 19.2% by Yang et al.,[13] and 20% by Broom et al.).[17] Prospective analysis, taking into account factors such as the time interval between the onset of symptoms, evaluation and intervention, nutrition, environment, and genetic profile, will address the underlying causes for this variation.

In summary, the rate of thyroid malignancies in AA versus the general population in previous studies did not demonstrate a concordance of the results. Lack of concordance may be attributable to many factors including small number of cases, difference in study designs, difference in parameters examined, and absence of cytopathological correlation.[125711] In contrast, our study is the only study of its type looking at preoperative FNA results and surgical pathology follow-up. More studies are needed to gain an insight into whether the difference is real, and if so, what factors cause this difference. We are in the process of adding cases to our database as well as embarking on looking at the genetic expression of thyroid lesions in AA versus NAA. The possible clinical applications of this observation include, but are not limited to, enhancing our ability to triage patients with TBS-Thy class III lesions. We feel that a multi-institutional study may be of value in exploring the study of race-based differences.

COMPETING INTERESTS

No competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author. Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from institutional review board (IRB) of all the institutions associated with this study. All authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

EDITORIAL / PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2012/9/1/7/94274.

REFERENCES

- The basis of racial differences in the incidence of thyroid cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1169-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2007. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007/, based on November 2009 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2010

- [Google Scholar]

- GLOBOCAN 2008, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No. 10. 2010. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/factsheets/populations/factsheet.asp?uno=991

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of race on thyroid cancer care in an equal access healthcare system. Am J Surg. 2010;199:685-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distribution of the bethesda system-thyroid diagnostic categories in African American population: Initial report of an Urban Institutions Experience. Cancer Cytopathol. 2010;118:348-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology definitions, criteria and explanatory notes. New York: Springer Science Business Media; 2010.

- [Google Scholar]

- The National Cancer Institute Thyroid fine needle aspiration state of the science conference: a summation. 2008. Cytojournal. 5:6. Available from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2008/5/1/6/41200

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic terminology and morphologic criteria for cytologic diagnosis of thyroid lesions: A synopsis of the National Cancer Institute Thyroid Fine-Needle Aspiration State of the Science Conference. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:425-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid cancer incidence and survival in the national cancer institute surveillance, epidemiology, and end results race / ethnicity groups. Thyroid. 2010;20:465-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodules: a study of 4703 patients with histologic and clinical correlations. Cancer. 2007;111:306-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignancy risk for fine-needle aspiration of thyroid lesions according to the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:450-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contribution of molecular testing to thyroid fine-needle aspiration cytology of “follicular lesion of undetermined significance / atypia of undetermined significance”. Cancer Cytopathol. 2010;18:17-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytology follow-up analysis of the Bethesda System-Thyroid diagnostic category follicular lesions of unknown significance (category III) in African Americans versus non-African Americans. Cytojournal. 2011;8:55.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of atypia / follicular lesion of undetermined significance on the rate of malignancy in thyroid fine-needle aspiration: evaluation of the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Surgery. 2011;150:1234-41.

- [Google Scholar]