Translate this page into:

Adult exogenous lipoid pneumonia: A rare and underrecognized entity in cytology – A case series

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Exogenous lipoid pneumonia (ELP) is a rare benign entity without specific clinical or imaging presentation. Although cytological studies – either bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or fine-needle aspiration (FNA) – may be pursued in patients with ELP, a definitive diagnosis is frequently rendered only on histology. The aim of this study is to highlight the cytological features of ELP.

Methods:

A search of cytopathology (CP) and surgical pathology (SP) diagnoses of ELP was conducted. The corresponding clinical and imaging features were obtained, and the morphology, particularly the presence and size of the intracytoplasmic vacuoles and background, was assessed.

Results:

Nine cases of ELP were identified, including eight with corresponding CP and SP. A neoplasm was suspected in three based on imaging, but ELP was not in the differential clinically or radiographically in any. Among the cases, six patients had BALs and three FNAs. All of the samples showed multiple large vacuoles within macrophages with at least some equal to or larger than the size of the cell nucleus. Similar vacuoles were noted extracellularly on smears.

Conclusions:

ELP is typically described in case reports in the clinical or radiological literature. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the largest series of adult ELP in CP. When large vacuoles are present in macrophages in cytology specimens, at least a suspicion of ELP can be suggested to initiate appropriate therapy, identify/remove the inciting agent, and preclude a more invasive procedure.

Keywords

Bronchoalveolar lavage

fine needle aspiration

lipid laden macrophages

lipoid pneumonia

lung

neoplasm

INTRODUCTION

Exogenous lipoid pneumonia (ELP) is an uncommon entity[1] without specific imaging features or clinical presentation. On chest computerized tomography (CT), it may appear as consolidation, ground-glass opacities (GGO), “crazy-paving” pattern (i.e., thickened interlobular septa superimposed on a GGO reminiscent of irregular paving stones), interstitial thickening,[123] or a mass. Clinically, ELP is described across all ages, but those at the extremes – the elderly and children – are at greatest risk. Predisposing factors include developmental disabilities,[4] anatomical anomalies such as Zenker's diverticulum and hiatal hernia,[5] loss of consciousness,[1] gastroesophageal reflux, dysphagia, neurologic disease,[4] alcohol abuse,[1] cerebral infarction,[1] tracheal stoma,[1] and illicit drug dependence.[1] ELP may have an acute presentation with fever and cough or it may be asymptomatic, especially in its chronic form. Most commonly, ELP is associated with aspiration of mineral oil, but vegetable and animal oils and other inhalants such as nasal ointments/drops and occupation-related substances are also implicated.[67891011121314]

The clinical symptoms and radiographic signs of ELP are nonspecific, with a history of mineral oil (or other inhalant) use rarely elicited or provided at initial presentation. Depending on the clinical presentation and imaging studies, however, the diagnosis may be pursued in one of two ways – with cytology sampling (bronchoalveolar lavage [BAL] or fine-needle aspiration [FNA]) or a biopsy. Despite the fact that cytologic material is obtained in patients, ELP is underrecognized on cytology, and clinicians frequently resort to performing transbronchial or surgical lung biopsies for ultimate diagnosis.[1516] Furthermore, many of the descriptions of ELP are in the clinical and radiological literature with those in the cytology and surgical pathology literature limited often to case reports making it a low diagnostic consideration. The aim of this study, therefore, was to highlight cytological features of ELP and thereby to increase recognition of this entity by cytopathologists and cytotechnologists.

METHODS

Following approval of the Institutional Review Board, a retrospective computerized search was performed to identify SP and cytopathology cases with the diagnosis (suspicion) of lipoid pneumonia. Additional cases with suspected lipoid pneumonia were also selected. All available CP slides from BALs and FNAs, and follow-up biopsies when available, as well as clinical history and radiologic reports were reviewed.

BAL specimens were received fresh or in CytoLyt. From the BALs, a Pap-stained ThinPrep (TP) slide was prepared, and in some instances, from the residual specimen, a formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded cell block (CB) was prepared. An Oil Red O stain was performed on cytospin slides when an unfixed BAL specimen was available and lipoid pneumonia was suspected. FNAs included smears with or without TP and CB.

All slides were evaluated for the presence of vacuoles in macrophages, with “large” defined as at least some vacuoles being equivalent to or larger than the size of the cell nucleus. The background was also evaluated for similar extracellular vacuoles and inflammation. When available, the Oil Red O stain was reviewed for the amount of lipid content (e.g., abundant versus sparse lipid droplets and size of droplets). The clinical history and interpretation of the imaging were recorded.

RESULTS

Clinical findings

Nine cases were identified. Eight had both CP and SP, and one had only CP with a corresponding Oil Red O stain; all biopsies were taken concurrently with BALs or FNAs. The cohort was collected from five men and four women with average age of 68 (range 53–77). All patients had a history of compromised immune system, recurrent respiratory infections, and/or were at high risk for aspiration secondary to conditions such as stroke, prior malignancy or esophageal disorder. No information was available regarding mineral oil use or other oily substances for any of the subjects.

Radiologic findings

CT imaging demonstrated confluent/nodular opacities (6), GGO (3), an infiltrate (1), tree-in-bud pattern (i.e., centrilobular nodules with a linear branching pattern resembling a branching tree with buds) (2), and/or spiculated mass (2) [Table 1]. Two demonstrated an interval increase and one decreased over a few months. Three were suspicious for malignancy, including one with GGO and confluent opacity, for which mucinous adenocarcinoma was in the differential.

Cytomorphologic findings

There were six BALs and three FNAs. The diagnosis of five BALs and three FNAs with histologically confirmed ELP was negative for malignant cells. Three of five BAL cases and two FNA cases had microscopic descriptive diagnoses that included pulmonary alveolar macrophages (PAMs) and multinucleated giant cells. ELP was suspected and indicated in the final diagnosis of two FNAs and one BAL without a corresponding SP.

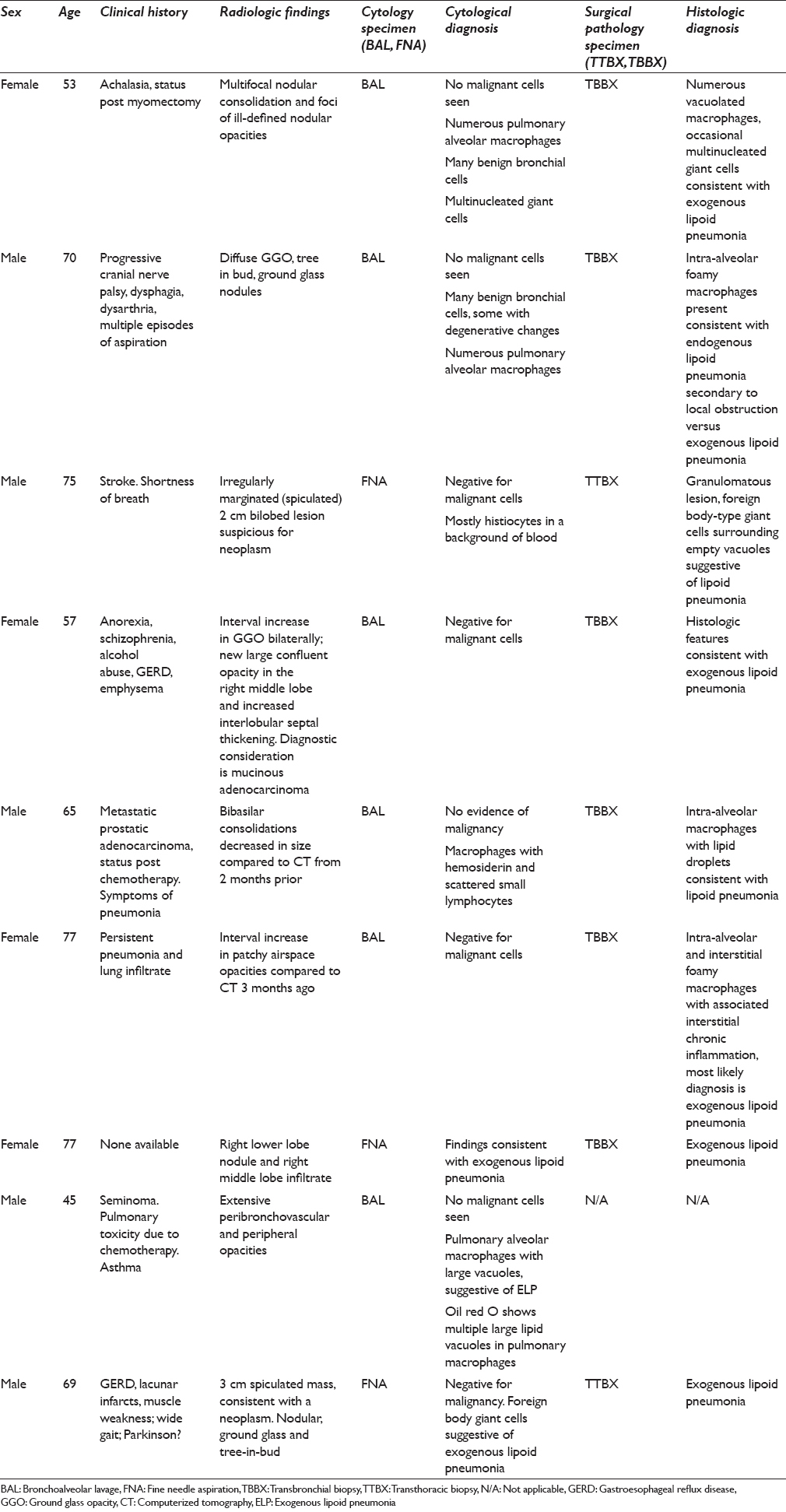

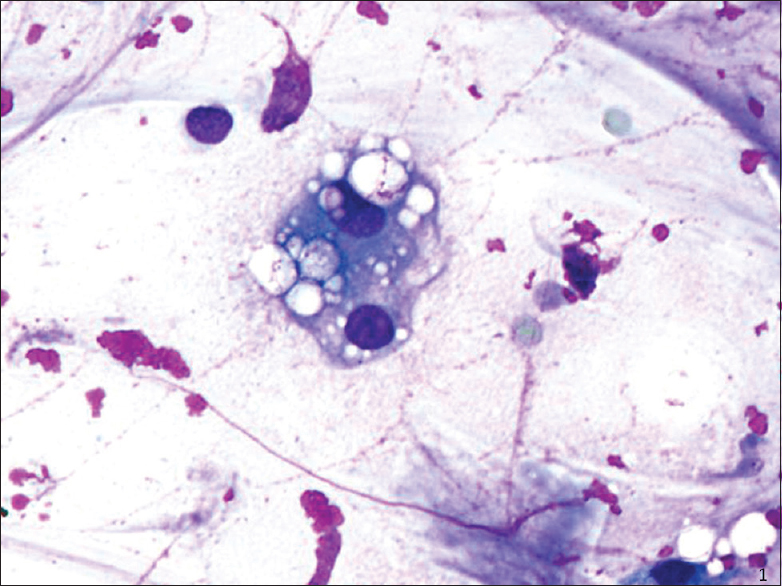

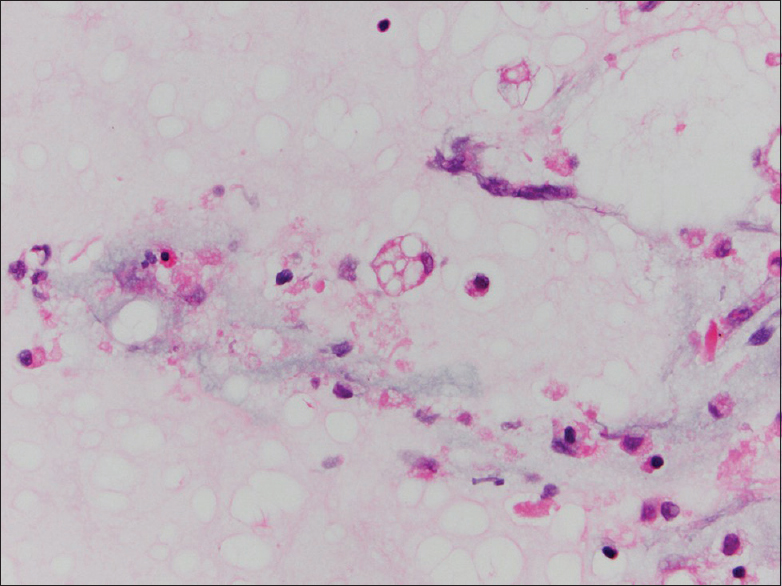

On intermediate and high magnification, the PAMs in all CP cases were noted to have distinct clear large vacuoles variable in number; PAM with fine cytoplasmic granularity representing uninvolved cells were also noted in the background [Figures 1–3]. An Oil Red O stain was performed in one case on a cytospin slide that was received unfixed and suspected to represent ELP [Figure 3 inset]. Rare bi- and multinucleated cells containing the same large vacuoles were also present. In the FNA smear samples, the background demonstrated variable-sized empty vacuoles that appeared bubble-like on low power. This was best appreciated on the Diff-Quik-stained smears. These acellular empty vacuoles were not identified in BAL specimens, likely due to more extensive fixation and processing for TP. Multinucleated giant cells and scant scattered inflammatory cells including lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and rare eosinophils were also noted. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages were described in one case.

- Fine-needle aspiration (smear, Diff-Quik stain): Multivacuolation in bi-nucleate cell and extracellularly

- Bronchoalveolar lavage (cell block, H and E stain): Multivacuolated cell with soap-bubble like cytoplasm representing ghosts of lipid vacuoles

- Bronchoalveolar lavage (ThinPrep, Papanicolaou stain): Multiple cells with large vacuoles containing lipid characteristic of exogenous lipoid pneumonia (center) and uninvolved smaller macrophage with finely vacuolated/granular cytoplasm (bottom right). Oil Red O stain bronchoalveolar lavage (cytospin, Oil Red O stain) inset: Lipid containing cells have abundant droplets including large and small

Histological findings

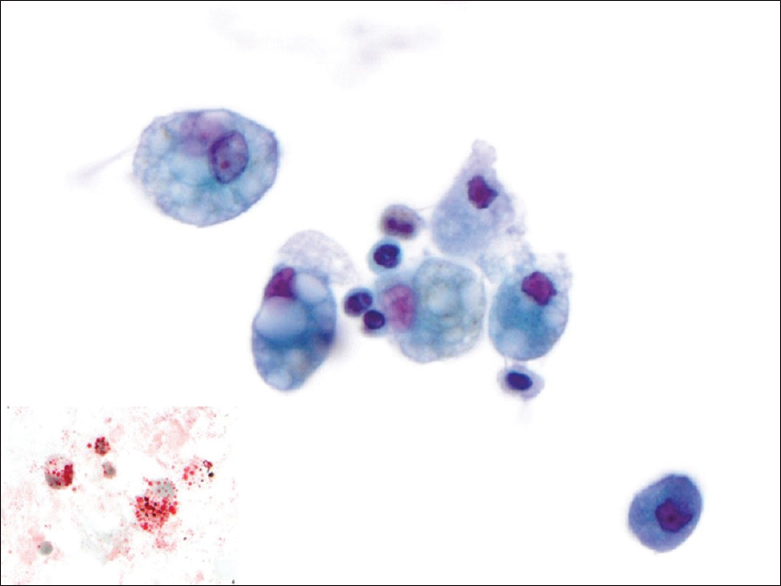

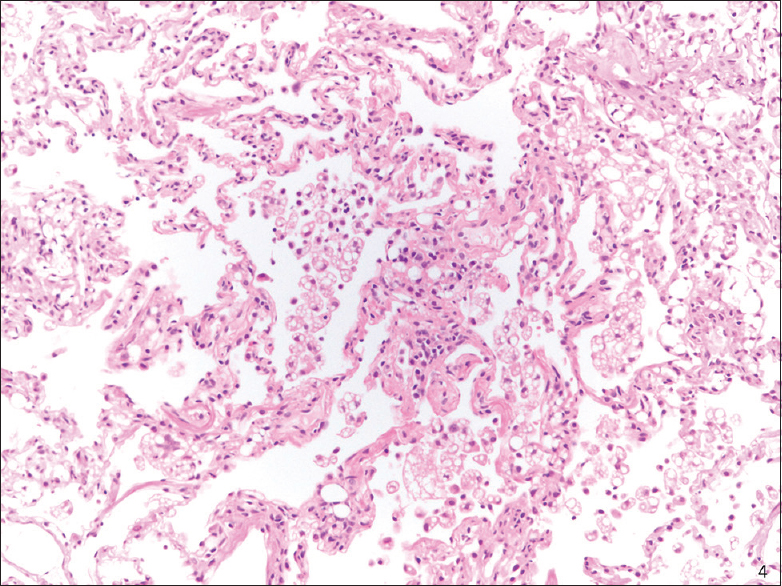

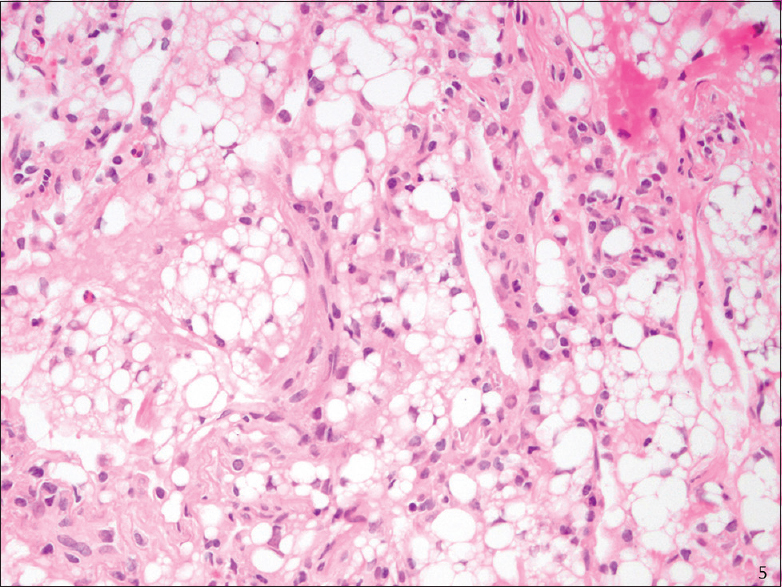

All of the SP cases were reviewed, and a diagnosis of ELP was confirmed. The SP cases, like the cytology cases, showed numerous intra-alveolar macrophages containing distinct intracytoplasmic vacuoles of varying sizes with rare bi- or multi-nucleated cells [Figures 4 and 5]. Rare scattered inflammatory cells were also present in SP cases in a ratio similar to those in the BAL/FNA samples.

- Transbronchial biopsy (H and E stain): Exogenous lipoid pneumonia, low magnification

- Transbronchial biopsy (H and E stain): Exogenous lipoid pneumonia, high magnification

DISCUSSION

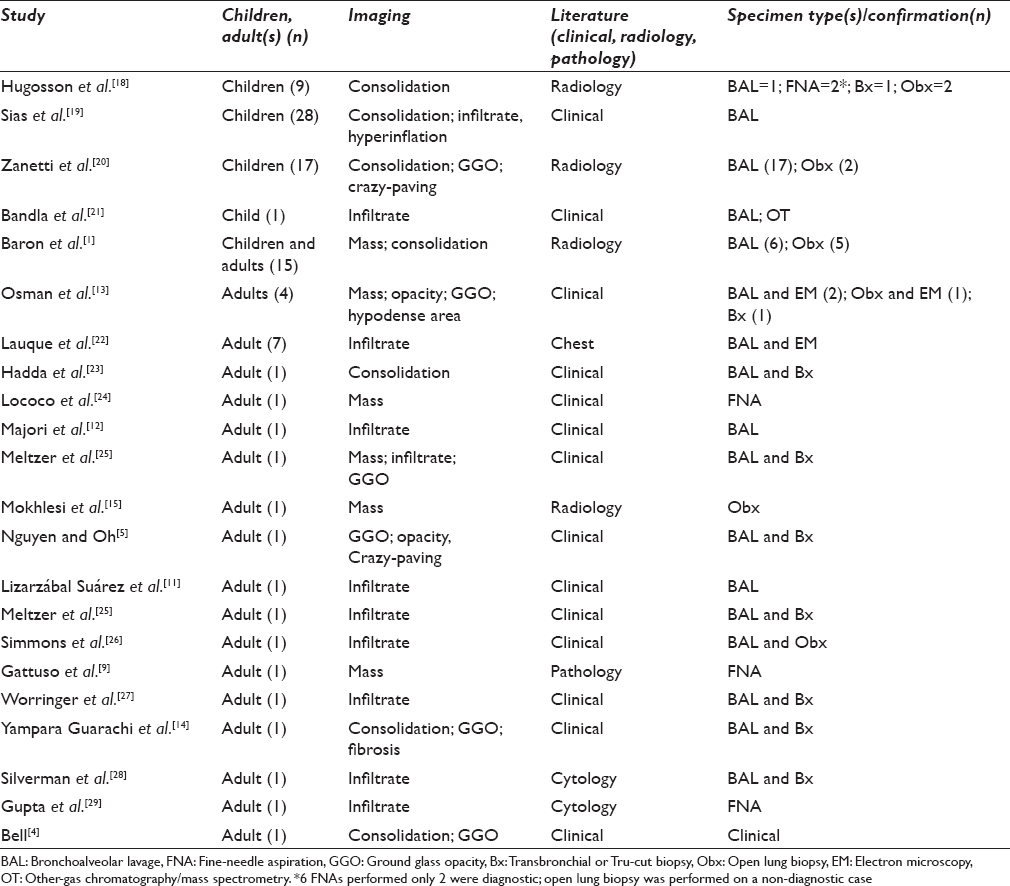

ELP is a well-recognized entity most frequently diagnosed on surgical biopsies and surgically resected specimens but is often unrecognized or not explicitly diagnosed on cytology alone. Specific benign diagnoses in cytology are most often limited to granulomas[17] and infections. Other entities, such as pulmonary alveolar proteinosis and organizing pneumonia,[17] may not be diagnosed as such without prompting by the clinical history, and the same may hold true for ELP. This is further compounded by its rarity and nonspecific clinical and imaging presentation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest series of cytology ELP in the literature [Table 2].

Although the architecture seen in SP specimens may not be evident in CP specimens, BALs and FNAs of ELP have the same characteristic large vacuolated cells. These are frequently overlooked, and the correct cytologic diagnosis of ELP was only made in 33% of the cases reported here; all of CP cases were noted to be negative for malignant cells, however. The diagnosis is typically confirmed by additional measures – either biopsy or Oil Red O stain – in many instances, as noted in six of nine cases in our series. This is not surprising as the cytology literature on this subject is sparse with most cases of ELP in the adult population appearing as case reports in the clinical or radiological literature. There are larger series of ELP in the pediatric population, but these too are restricted primarily to the pediatric and radiology journals [Table 2]. In both populations, BAL is the most common mode of cytology sampling, and a biopsy or another modality is pursued for confirmation. The purpose of this manuscript is to highlight features of ELP in cytology.

There are two types of lipoid pneumonia, endogenous and exogenous. While endogenous lipoid pneumonia is typically due to an accumulation of lipid-containing macrophages distal to an area of obstruction, infection, or lipid storage disease,[3031] ELP results from oral ingestion and aspiration of foreign material, with mineral oil, often used as a form of laxative or for ascaridiasis,[19] being the leading culprit. Other oils and agents implicated include animal fat,[3] vegetable oil,[3] castor oil,[4] shark liver oil (squalene),[4] lip gloss,[32] Vaseline,[6] Vicks,[6] polyurethane,[1] diesel (contains mineral oil), “ghee” (clarified butter),[1833] and spray lubricant (WD-40).[10] Certain occupations (e.g., fire-eaters[3]) with exposures to lubricants, paints,[34] pesticides,[3] and other substances may predispose individuals to ELP as well. Moreover, ELP is not restricted to oral ingestion and also described with nasal intake of substances.

The morphology of ELP, at least in the case of mineral oil,[1] is attributed to the inability of enzymes to metabolize the nonsaponifiable substances that are absorbed by macrophages.[1] Once the macrophages die, they release their contents perpetuating the cycle.[18] When this process is long-standing, it results in fibrosis.[1] Similarly, vegetable oils also produce a minimal inflammatory response.[3] At least in the case of mineral oil, gag reflex,[18] cough, and mucociliary elevator functions are suppressed.[18]

Although patients may have a history of aspiration or inhalation of ELP causing agents, this information is often undiscovered at the time of initial presentation.[22] ELP was not diagnosed on cytology in six of nine cases in our study set. The presenting symptoms and signs were shortness of breath, recurrent pneumonia, persistent imaging abnormalities, history of aspiration, esophageal dysfunction, reflux, and immunocompromised status. ELP may be acute due to a massive exposure[23] or more commonly chronic[1] with clinical findings ranging from asymptomatic to nonspecific symptoms of cough, dyspnea, fever,[4] shortness of breath,[23] and hemoptysis.[26] Many ELP patients can present with signs and symptoms mimicking infectious pneumonia and can sometimes mimic a neoplastic process[13] as noted in three of the cases in the current cohort.

The imaging was concerning for a neoplasm in three of our cases. When present, recognition of fat attenuation on CT is a clue to the diagnosis,[1] but more often, the findings are nonspecific[35] with a broad differential spanning from neoplastic[1524] to nonneoplastic processes including pneumonia and granuloma.[2318] ELP is more likely to manifest in the lower lobes bilaterally with consolidation, GGOs, septal thickening,[4] infiltrates,[1] atelectasis,[1] fibrosis,[1] interstitial lung disease,[23] and crazy paving;[3] pleural effusions are described in acute ELP. Chronic disease is more likely to appear as single or multiple[3] nodules or masses,[1] which may be regular or spiculated[3] and demonstrate progression[1] and increased PET activity[1516] when accompanied by an inflammatory component making the distinction between ELP and a neoplasm difficult.[336]

In our series, the diagnosis of ELP was rendered in three of nine cytology cases, including BAL (n = 1) and FNA (n = 2), and two of these had concurrent biopsies. This is similar to the data in the literature, in which most cases of ELP on BAL were confirmed by another modality [Table 2] with only rare examples of primary diagnosis on cytology.[7] On SP, ELP has a characteristic morphology. The macrophages in ELP have at least some large vacuoles accompanied by a foreign body giant cell reaction, chronic inflammation, and/or fibrosis elicited by the “lipoid” material. This is in contrast to endogenous lipid pneumonia, which contains foamy or finely vacuolated macrophages. Similarly, in the cytology specimens, the vacuoles were large (at least some as large as the cell nucleus) and variable in size. Although the lack of an identifiable source for ELP is a shortcoming of this study, the histology corroborates the findings in eight of nine cases.

Pediatricians often request for evaluation of lipid-laden alveolar macrophages (LLAM) in children, because some medical or structural conditions predispose this population to aspiration leading to ELP.[19193738] In the adult patients’ population, however, clinicians may not suspect and/or fail to inform the cytopathologist of relevant clinical history. In our series, in 6 of 8 cases that had corresponding SP and CP, the diagnosis of ELP was not considered on CP specimens. On retrospective review of the slides, numerous multivacuolated macrophages were present on the smears, TP, and/or CB slide(s).

Not all multivacuolated macrophages are LLAMs. PAMs have variable cytoplasm that may be foamy, finely vesiculated, or vacuolated. Multivesiculation may represent an acute inflammatory process, drug toxicity (e.g., amiodarone),[39] infection (e.g., Rhodococcus equi),[39] or other reactive conditions.[39] In some of these conditions (i.e., amiodarone and Rhodococcus equi), the macrophages have foamy to finely vacuolated cytoplasm, in contrast to the large vacuoles of ELP, and lack multinucleated foreign body giant cells,[39] and in the case of amiodarone, the multivesiculation is present in the pneumocytes as well.[39] Performing special stains, such as Oil Red O or Sudan B, can be useful in confirming the morphological impression of ELP.[283840] An Oil Red O stain can be performed on an unfixed smear or cytospin slide. To do so, the diagnosis has to be clinically suspected, so the specimen is not submitted in alcohol-based fixatives or formalin-fixed and paraffin embedded – both remove the lipids and decrease the sensitivity of these tests. Minimal staining does not correlate with ELP[28] because such lipid-laden macrophages may also be seen other settings including endogenous lipid pneumonia[41] and proteinosis.[42] Oil Red O staining can also be seen in the cytoplasm of neutrophils.[42] Some authors have proposed using a LLAM index,[40] in which the intracellular content of lipid within the macrophages is evaluated; the greater the number of droplets that occupy the cytoplasm and obscure the cytoplasm, the greater the specificity. Some state that finding extracellular lipid in BALs is more specific[35] because intracellular lipid can be seen in cases without ELP. When compared with other pathological states, Oil Red O staining was greatest in the setting of ELP.[42] A gross examination of the BAL provides a clue to the diagnosis, as oil droplets can be identified on the surface of the specimen.[1214192122] Other features that might be helpful in identifying ELP are foamy background with variable-sized empty vacuoles and multinucleated giant cells.

Recognizing ELP is important for several reasons. In cases with suspected infection, unnecessary antibiotic treatment can be obviated, unless of course there is suspicion of a superimposed infection. In instances of a mass lesion, invasive procedures (e.g., surgery) can be avoided. Recognizing ELP can prompt additional history to identify the culprit and prevent associated complications such as pulmonary fibrosis,[35] superimposed infection,[35] and cor pulmonale.[35]

CONCLUSIONS

Cytology, including BALs and FNAs, is used frequently to assess abnormal features detected on chest imaging. From the data, it can be inferred that ELP, though diagnosed as benign on cytology specimens, may not be specific and overlooked. Awareness of distinct large clear vacuoles in variable numbers and sizes within macrophages and extracellularly is key in diagnosing ELP on cytology and preventing false-negative diagnosis.[7] A correct diagnosis or suggestion of ELP may avoid further unnecessary procedures and initiate appropriate management.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the institution associated with this study (Columbia University Medical Center). Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

BAL - Bronchoalveolar lavage

Bx - Transbronchial or Tru cut biopsy

CB - Cell block

CP - Cytopathology

CT - Computerized tomography

ELP - Exogenous lipoid pneumonia

EM - Electron microscopy

FNA - Fine needle aspiration

GERD - Gastroesophageal reflux disease

GGO - Ground glass opacity

LLAM - Lipid laden alveolar macrophages

Obx - Open lung biopsy

OT - Other gas chromatography/mass spectrometry

PAMs - Pulmonary alveolar macrophages

SP - Surgical pathology

TBBX - Transbronchial biopsy

TP - ThinPrep

TTBX - Transthoracic biopsy

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Radiological and clinical findings in acute and chronic exogenous lipoid pneumonia. J Thorac Imaging. 2003;18:217-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exogenous lipoid pneumonia: HRCT, MR, and pathologic findings. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:1190-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipoid pneumonia: Spectrum of clinical and radiologic manifestations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:103-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipoid pneumonia: An unusual and preventable illness in elderly patients. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61:775-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exogenous lipoid pneumonia due to nasal application of petroleum jelly. Chest. 1994;105:968-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exogenous lipoid pneumonia: Importance of clinical history to the diagnosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2006;32:596-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipoid pneumonia associated with lipid-containing nasal sprays and nose drops. Laryngorhinootologie. 2016;95:534-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exogenous lipoid pneumonitis due to vicks vaporub inhalation diagnosed by fine needle aspiration cytology. Cytopathology. 1991;2:315-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exogenous lipoid pneumonia due to inhalation of spray lubricant (WD-40 lung) Chest. 1990;97:1265-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipoid pneumonia due to accidental aspiration of paraffin in a “fire-eater”. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51:530-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipoid pneumonia as a complication of Lorenzo's oil therapy in a patient with adrenoleukodystrophy. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2014;21:271-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exogenous lipoid pneumonia induced by nasal decongestant. Clin Respir J. 2016;12:524-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- False-positive FDG-PET scan secondary to lipoid pneumonia mimicking a solid pulmonary nodule. Ann Nucl Med. 2007;21:411-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exogenous lipoid pneumonia with unusual CT pattern and FDG positron emission tomography scan findings. Eur Radiol. 2002;12(Suppl 3):S171-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Granulomatous inflammation and organizing pneumonia: Role of computed tomography-guided lung fine needle aspirations, touch preparations and core biopsies in the evaluation of common non-neoplastic diagnoses. Cytojournal. 2014;11:2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipid-laden bronchoalveolar macrophages in asthma and chronic cough. Respir Med. 2014;108:71-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipoid pneumonia in infants: A radiological-pathological study. Pediatr Radiol. 1991;21:193-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evolution of exogenous lipoid pneumonia in children: Clinical aspects, radiological aspects and the role of bronchoalveolar lavage. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35:839-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipoid pneumonia in children following aspiration of mineral oil used in the treatment of constipation: High-resolution CT findings in 17 patients. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:1135-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipoid pneumonia: A silent complication of mineral oil aspiration. Pediatrics. 1999;103:E19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipoid pneumonia presenting as non resolving community acquired pneumonia: A case report. Cases J. 2009;2:9332.

- [Google Scholar]

- Idiopathic lipoid pneumonia successfully treated with prednisolone. Heart Lung. 2012;41:184-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipoid pneumonia: A preventable form of drug-induced lung injury. Eur J Intern Med. 2005;16:615-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Not your typical pneumonia: A case of exogenous lipoid pneumonia. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1613-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bronchoalveolar lavage in the diagnosis of lipoid pneumonia. Diagn Cytopathol. 1989;5:3-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Image-guided aspiration cytodiagnosis of lipid pneumonia. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;30:290-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipoid pneumonia in an adolescent girl secondary to use of lip gloss. J Pediatr. 1984;105:421-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipoid pneumonia in children following aspiration of animal fat (ghee) Ann Trop Paediatr. 1991;11:87-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute lipoid pneumonia caused by accidental aspiration of vaseline used in nasogastric intubation. Arch Bronconeumol. 2000;36:485-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exogenous lipoid pneumonia. clinical and radiological manifestations. Respir Med. 2011;105:659-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exogenous lipoid pneumonia in children: A disease to be reminded of. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2012;58:135-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The cytologic evaluation of lipid-laden alveolar macrophages as an indicator of aspiration pneumonia in young children. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:229-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multivesiculated macrophages: Their implication in fine-needle aspiration cytology of lung mass lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 1998;19:98-101.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oil red O stain of alveolar macrophages is an effective screening test for gastroesophageal reflux disease in lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:859-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cut-off values and significance of oil red O-positive cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Cytopathology. 2010;21:245-50.

- [Google Scholar]