Translate this page into:

An unusual case of Primary Effusion Lymphoma with aberrant T-cell phenotype in a HIV-negative, HBV-positive, cirrhotic patient, and review of the literature

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is an unusual, human herpes virus-8 (HHV-8)–associated type of lymphoma, presenting as lymphomatous effusion in body cavities, without a detectable tumor mass. It primarily affects human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients, but has also been described in other immunocompromised individuals. Although PEL is a B-cell lymphoma, the neoplastic cells are usually of the ‘null’ phenotype by immunocytochemistry. This report describes a case of PEL with T-cell phenotype in a HIV-negative patient and reviews all the relevant cases published until now. Our patient suffered from cirrhosis associated with Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and presented with a large ascitic effusion, in the absence of peripheral lymphadenopathy or solid mass within either the abdomen or the thorax. Paracentesis disclosed large lymphoma cells with anaplastic features consisting of moderate cytoplasm and single or occasionally multiple irregular nuclei with single or multiple prominent nucleoli. Immunocytochemically, these cells were negative for both CD3 and CD20, but showed a positive reaction for T-cell markers CD43 and CD45RO (VCHL-1). Furthermore, the neoplastic cells revealed strong positivity for EMA and CD30, but they lacked expression of ALK-1, TIA-1, and Perforin. The immune status for both HHV-8 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) was evaluated and showed positive immunostaining only for the former. The combination of the immunohistochemistry results with the existence of a clonal rearrangement in the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (identified by PCR), were compatible with the diagnosis of PEL. The presence of T-cell markers was consistent with the diagnosis of PEL with an aberrant T-cell phenotype.

Keywords

Cirrhosis

HHV-8

HIV

HBV

primary effusion lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

It was Cesarman and colleagues. in 1995, who first identified KSHV DNA sequences within a distinct subgroup of AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) localized in body cavities, presenting as lymphomatous effusions.[1] Subsequently, Nador et al. (1996) introduced the term ‘primary effusion lymphoma’ (PEL) in order to describe this particular type of lymphoma, which was lacking a tumor mass, but was accompanied by HHV- 8 infection.[2] According to the definition provided by the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues (issue 2008), the primary effusion lymphoma is a large B-cell neoplasm that usually presents as a serous effusion without a detectable tumor mass and is universally associated with HHV-8. Some patients with PEL, secondarily develop solid tumors in the adjacent structures, such as, the pleura, whereas, rare cases of HHV-8-positive lymphomas (indistinguishable from PEL) present as solid tumor masses, and have acquired the designation of extracavitary PEL.[3] Furthermore, PEL is included in the category of HIV-associated lymphomas, having been referred in the literature as ‘lymphomas occurring more specifically in HIV-positive patients’,[4] although it has been almost simultaneously reported in HIV-negative patients also.[5–7] In this setting PEL has been linked to other immunodeficiency conditions, such as, following an organ transplantation,[8–10] cancer,[1112] old age,[1314] or even cirrhosis.[1516] There are also published reports that describe PEL associated with liver cirrhosis and as a simultaneous infection with either Hepatitis B or C virus.[1718]

As far as cytomorphology is concerned, PEL shows features bridging immunoblastic and anaplastic large-cell lymphomas, with a frequent demonstration of plasma cell differentiation. Interestingly, PEL exhibits a ‘null’ immunophenotype, as it lacks expression of both B- and T-cell associated antigens.[5]

We herein report a case of HIV-negative PEL, with underlying Hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related liver cirrhosis, which additionally showed the relative infrequent immunocytochemical expression of T-cell associated antigens. Our case was also positive for HHV-8, a finding that along with the particular cytomorphological and immunocytochemical findings, confirmed that the lymphomatous effusion was a case of PEL.

CASE REPORT

Clinical summary

The patient was an 88-year-old man of Mediterranean descent, with a history of cirrhosis and underlying HBV infection. At the time of presentation in the clinic, he complained of generalized weakness and fatigue over the last month. Physical examination revealed icterus of the skin and sclera, as well as abdominal distention, owing to the presence of ascitic fluid without any detectable hepatosplenomegaly.

The peripheral blood count showed macrocytic anemia (Hb: 11,6 g / dL, MCV: 108,0 fL), thrombocytopenia (PLT: 113 × 103/ μL) and normal WBC count and differential. In particular, the exact values were as follows: WBC: 4,0 × 103/ μL, Neut.: 72%, Lymph.: 18%, Mono.: 9,0%, Eosino.: 1,0%, RBC: 3,09 × 106/ μL, Hb: 11,6 g / dL, MCV: 108,0 fL, MCH: 37,6 pg, and PLT: 113 × 103/ μL. His serum profile provided the following results: Gluc: 105,0 mg / dl, UREA: 32,0 mg / dL, CREAT: 0,88 mg / dL, SGOT: 223,0 U / L, SGPT: 155 U / L, T-Bil.: 7,0 mg / dL, Bl-Bil.: 3,0 mg / dL, γ-GTP: 50 U / L, ALP: 165 U / L, LDH: 241 U / L, Prot: 7,4 g / dL, Alb: 2,1 g / dL, CK: 183 U / L. The biochemical examination of the collected peritoneal fluid revealed: Gluc 111 mg / dL, Prot: 2,2 g / dL, Alb: 0,65 g / dL, LDH: 1590 U / L, Chol: 7,0 mg / dL, and Trigl: 16 mg / dL.

Abdominal Ultrasound-Sonography (US) demonstrated liver cirrhosis and massive ascites. Computed-Tomography (CT), which was carried out later confirmed the ascites, although with no visible peritoneal implants. Furthermore, no pathological lymphadenopathy was detected by the obtained CT-scans.

Paracentesis was performed, yielding a large amount (800 ml) of ascitic fluid that was subsequently sent for cytological evaluation. After centrifugation of the sample, the sediment was used for ThinPrep preparation as well as for routine preparation, with direct smearing stained with both Pap and Giemsa. The remaining sediment was used for cell block preparation, using the plasma-thrombin method and standard H and E staining.

Cytological findings

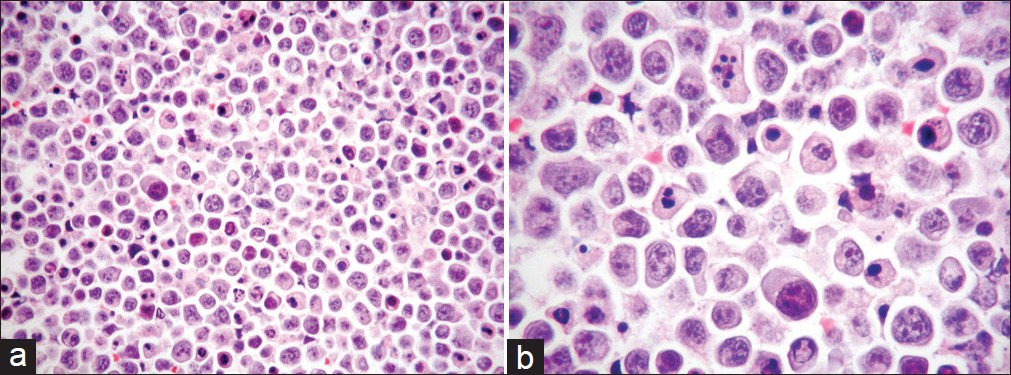

The Thin Prep material consisted of abundant large-sized malignant cells, with a moderate amount of basophilic cytoplasm, which were arranged singly. Most of them had a single nucleus, but occasionally, bi-nucleated or multinucleated cells were also seen. The nucleus had coarse chromatin pattern, irregular nuclear outlines, and a single or multiple prominent nucleoli. A high mitotic activity, with abnormal mitoses was present, and a large number of apoptotic bodies as well as nuclear debris were additionally seen [Figures 1a and 1b].

- (a) Cell block of FNA material showing a striking nuclear pleomorphism as well as a high mitotic index with irregular mitoses and numerous apoptotic bodies (H and E stain, magnification ×200). (b) Higher magnification of the a, with particular emphasis on the details noted above (H and E stain, magnification ×400)

Immunocytochemistry

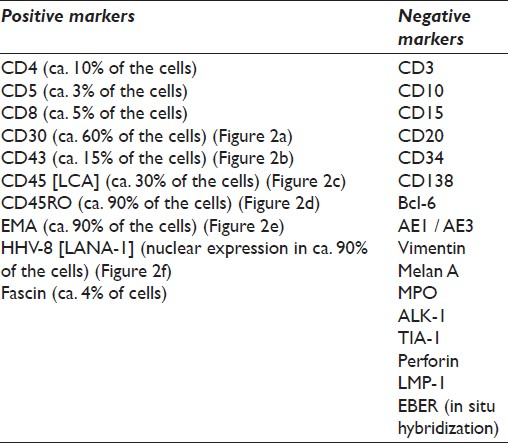

The immunophenotypic profile of the tumor was determined by standard immunoperoxidase methods using paraffin sections from cell block material. The primary antibodies used were: AE1 / AE3, EMA, Vimentin, Melan A, MPO, Fascin, Perforin, Bcl-6, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD8, CD10, CD15, CD20, CD30, CD34, CD43, CD45 (LCA), CD45RO, and CD138 antigens. In addition, anaplastic lymphoma kinase 1 (ALK-1) protein, TIA-1, LMP-1, and HHV-8 (Latent Nuclear Antigen-1; LANA-1) were also investigated. Antigen retrieval was performed using ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA)-based solution (CC1). The primary antibody, secondary antibody, and avidin-enzyme conjugate were then visualized using the precipitating enzyme diaminobenzidine (DAB). The detailed immunocytochemical list of the antibodies used in our case is depicted in Table 1.

Molecular analysis

A possible Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection was excluded using the EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) in situ hybridization test in cell block material. On the contrary, the infection with he Hepatitis B virus was further confirmed with the identification of the HBV-DNA. Moreover, sediment from the ascitic fluid was examined using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method to detect any clonal rearrangement of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (IgH). Moreover, we checked for gene rearrangement in the T-cell receptor. In particular, and in more detail, the methods used are described below and the obtained results are shown in the attached figures.

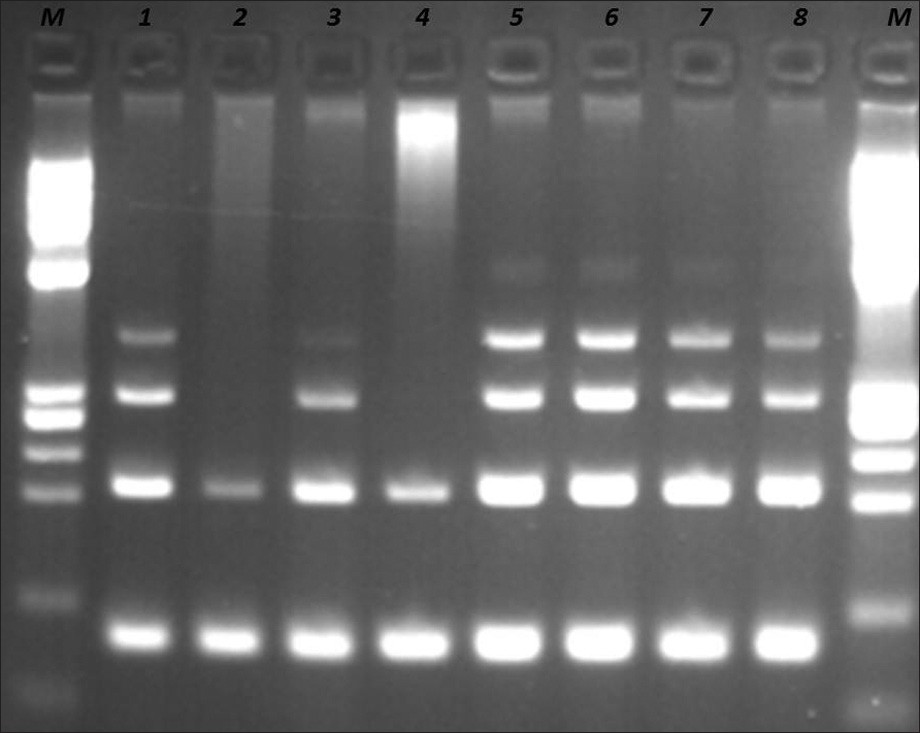

Molecular analysis was performed using the IdentiClone IgH Gene Clonality Assay kit (CE-IVD, InVivoScribe Technologies, USA). The DNA was extracted and amplified by primers that target the conserved framework of the variable (V) regions, the conserved joining (J) regions, as well as the diversity and joining regions, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The DNA quality was tested by the Specimen Control Size Ladder Mix, which contains multiple oligonucleotides targeting the housekeeping genes [supplied with the Kit, Figure 3].

![The performed immunocytochemistry (ICC) revealed among others, a positive reaction in the neoplastic cell population for (a) CD30 (magnification ×200), (b) CD43 (magnification ×200), (c) CD45 (magnification ×200), (d) CD45RO (magnification ×200), (e) EMA (magnification ×200), and (f) HHV-8 [LANA-1] (nuclear staining; magnification ×200)](/content/105/2012/9/1/img/CJ-9-16-g003.png)

- The performed immunocytochemistry (ICC) revealed among others, a positive reaction in the neoplastic cell population for (a) CD30 (magnification ×200), (b) CD43 (magnification ×200), (c) CD45 (magnification ×200), (d) CD45RO (magnification ×200), (e) EMA (magnification ×200), and (f) HHV-8 [LANA-1] (nuclear staining; magnification ×200)

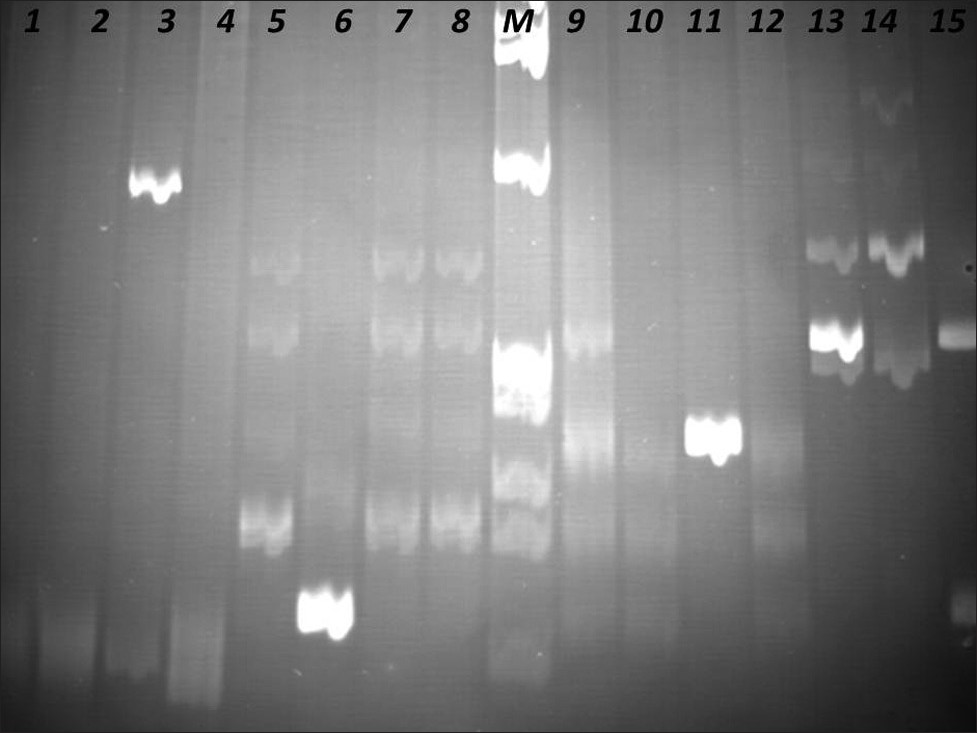

- DNA quality control by Specimen Control Size ladder mix supplied with the kit. Samples at positions 1, 5, 6, 7, and 8 are controls supplied with the kit. Samples at positions 2, 3, and 4 are from patients. Sample 3 is the requested sample. Samples 2 and 4 have bad quality of DNA. M: PhiX174 / HaeIII digest ladder (New England Biolabs).

The presence or absence of clonal T-cell Receptor Gamma chain gene rearrangements was evaluated using the IdentiClone TCRG Gene Clonality Assay (CE-IVD, InVivoScribe Technologies, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, as mentioned earlier.

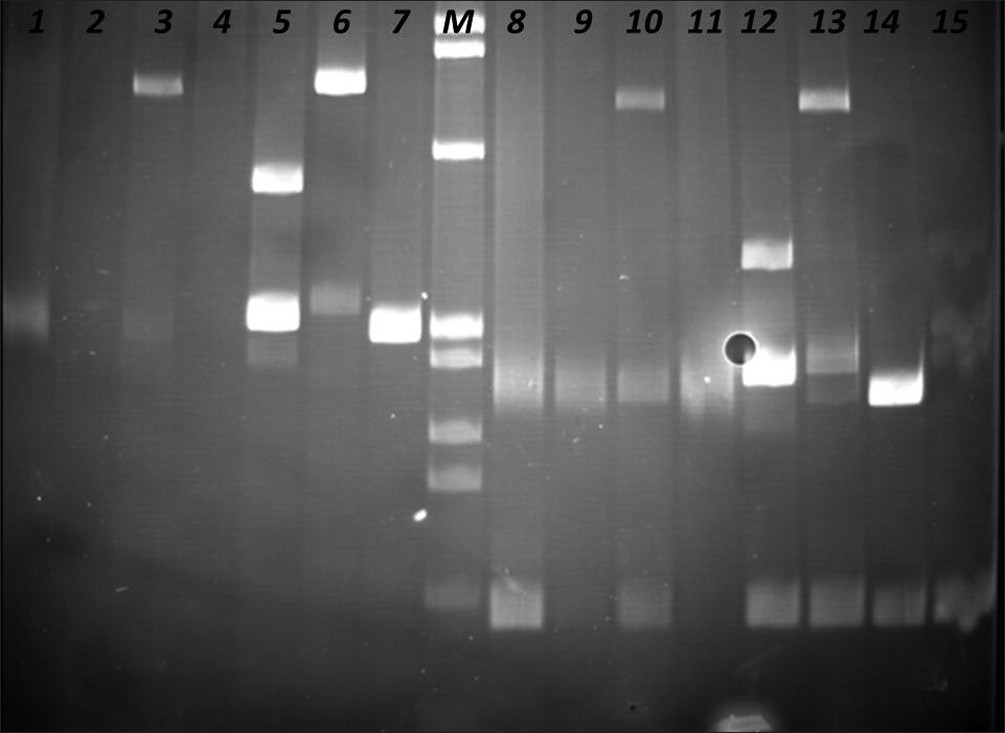

The PCR products were analyzed in agarose gel electrophoresis, followed by non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), in the presence of positive (clonal) and negative (polyclonal) controls [Figures 4–6].

- Identification of Clonal Immunoglobulin Heavy Chain Gene Rearrangements in non-denaturing polyacrylamide electrophoresis gels (PAGE). Positions 1 and 8 polyclonal controls, positions 2 –4, 9 – 11 samples, and positions 5 – 8, 12 – 16 clonal controls. Requested sample at positions 3 and 10.

- Identification of Clonal Immunoglobulin Heavy Chain Gene Rearrangements in non-denaturing polyacrylamide electrophoresis gels. Positions 1 and 9 polyclonal controls, positions 2 – 4, 10 – 12 samples, positions 5 – 8, 13 – 15 clonal controls. Requested sample at positions 3 and 11. M: PhiX174 / HaeIII digest ladder (New England Biolabs).

- Identification of Clonal T Cell Receptor Gamma Chain Gene Rearrangements in non-denaturing polyacrylamide electrophoresis gel (PAGE). Positions 1 and 9 polyclonal controls, positions 2 – 5, 10 – 13 samples, and positions 6 – 8, 14, and 15 clonal controls. Requested sample at positions 5 and 13. M: PhiX174 / HaeIII digest ladder (New England Biolabs).

Other laboratory tests

A bone-marrow aspirate showed no evidence of lymphoma. The serological investigation revealed the following results: HbsAg: (+), Anti-Hbc: IgG(+), Anti-Hbe: (-), HbeAg: (+), Anti-Hbs: (-), Anti-HCV: (-), and Anti-HIV: (-).

Final cytological diagnosis

The final diagnosis that was based on both cytological and immunocytochemical findings, in conjunction with the appropriate molecular workup, was indicative of primary effusion lymphoma with aberrant T-cell expression. The patient unfortunately died one week after the final diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Dissemination of Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (NHL) in serous cavity fluids has been reported in approximately 10% of all malignant effusions.[19] The term PEL was initially introduced by Nador et al., in 1996, in order to describe a novel type of lymphoma, presenting exclusively as a lymphomatous effusion in the absence of a detectable solid mass.[2] In a majority of lymphoma cases other than PEL, a precise subtyping of the neoplasm in cytological specimens is not required, as the actual diagnosis will have been already established in the solid parts of the tumor, before the acquisition of the cytological sample.[20] However, on some occasions where the serous cavity effusion is more accessible relative to the primary site of involvement, the cytological and immunocytochemical interpretation is, without doubt, of outmost importance, especially when a PEL diagnosis is under consideration.

As we have already mentioned above, primary effusion lymphoma has a strong association with HHV-8 infection, but it also seems to have a relative ‘preference’ for occurrence in HIV-positive individuals. Indeed, this unique type of lymphoma has been estimated to account for approximately 4% of NHL in HIV-positive patients, but only for 0.3% of NHL in HIV-negative patients.[21] In these cases, where the patients are HIV negative (as in our case; see also review of all published so far [HHV-8(+) and HIV(-)] cases in Table 2), other immunodeficient conditions may exist. Our patient, although negative for HIV infection, presented with liver cirrhosis associated with Hepatitis B virus. Cirrhosis, which is an established condition of immunodeficiency,[49] has been described in association with PEL; specifically there are a few reports that demonstrate the presence of PEL together with liver cirrhosis.[151647] Although a majority of PEL-cases referred to in literature are HHV-8 positive,[34] there are several examples in which the absence of HHV-8, with or without a simultaneous absence of HIV infection, has been observed.[50–53] These particular cases have been further referred in the literature as ‘HHV-8-unrelated PEL-like lymphomas’, in order to differentiate them from ‘true’ PEL. Therefore, the presence of HHV-8 has been established almost as a criterion, to consider a lymphoma as a PEL, as the former is considered to play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of the latter.[34] In this context, it has been proposed that the name PEL should be assigned only to this primary lymphomatous effusion that shows evidence of HHV-8 infection, along with the supportive morphological and immunophenotypical criteria.[5455] The standard assay to detect HHV-8 infection in tissues is the immunocytochemical staining for LANA-1,[56] whereas, EBV infection is most reliably identified by in situ hybridization for EBV-RNA, as immunocytochemical staining for EBV latent membrane protein (LMP-1) is almost always negative.[3] Accordingly, after completion of the relative tests, our case has shown the presence of HHV- 8 and the absence of EBV infection. Previous molecular studies have approved the occurrence of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements (this is also true in our case) and somatic hypermutation in PEL cells, indicating that the cell of origin is a post-germinal center B-cell.[57]

Similarly, the experiments carried out by Fais et al., further suggested that PEL originated from mature antigen-experienced B-cells. Specifically, this group performed sequencing-analysis in immunoglobulin (Ig) genes from seven AIDS-related PEL. The obtained results showed that most of the samples used lambda light chain genes, two cases expressed mu chains, whereas, gamma chains were also found in two cases. In all cases, significant deviations from the presumed germline counterpart were found in both the expressed VH and VL genes. Statistical evidence for antigen selection was evident in four out of the seven samples studied. Evidence for selection was more frequent in the light chain genes than in the heavy chain genes.[58] Gene expression profile analysis, which had already been performed in cases of AIDS-related PEL, had also confirmed a plasmablastic derivation.[36] The cells of PEL immunocytochemically exhibited an indeterminate or ‘null’ lymphocyte phenotype, a they showed positive staining for the leukocyte common antigen (LCA; CD45), but negative staining for both routine B-cell- (including surface and cytoplasmic immunoglobulin, CD19, CD20, CD79a) and T-cell-markers (CD3, CD4, CD8). Instead, various markers of lymphocyte activation (CD30, CD38, CD71, human leukocyte antigen DR) and plasma cell differentiation (CD138) are usually displayed.[545960] Unlike the majority of reported cases, which show—as noted before—a ‘null’ immunophenotype, our case expressed, to a variable extend, T-cell markers (such as CD4, CD8, CD43; Figure 2b) and CD45RO (Figure 2d), but showed no expression of the B-cell marker CD20.

The occurrence of a T-cell immunophenotype in PEL is a relatively rare event and only a few cases have been published until now.[333847516162] The differential diagnosis of PEL, on a cytomorphological ground, includes other large cell lymphomas, such as, anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), Burkitt lymphoma (BL), with plasmacytoid differentiation, and pyothorax-associated lymphoma (PAL). Among them, the Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL) and PEL share similar morphological and immunocytochemical characteristics. Morphologically, they are both high-grade lymphomas, composed of large cells with pleomorphic nuclei and prominent single-to-multiple nucleoli. However, the typical ‘hallmark cells’ with the eccentric kidney- or horseshoe-shaped nuclei and a prominent Golgi zone, which have been previously described in ALCL, are only seldom seen in PEL. Immunocytochemically both are positive for CD30 and EMA. Furthermore, ALCL demonstrates a T-cell immunophenotype. With regard to all the arguments raised herewith, while keeping in mind that our case also showed a T-cell profile, it was particularly difficult to rule out an ALCL. However, the negative immunostaining for ALK-1, in conjunction with the strong positivity for HHV-8, as it was a fact in our case, rendered the diagnosis of PEL as the most plausible.[63] The exclusion of the rest of the lymphoma subtypes from the final diagnosis was more obvious. As far as Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and in particular the immunoblastic variant is concerned, confusion may arise, as this may also show morphological features similar to PEL. However, both the immunophenotype and HHV-8 detection are helpful in distinguishing these two entities, as DLBCL expresses B-cell markers and is HHV-8 negative. Unlike the classic Burkitt lymphoma (BL), the variant of BL with plasmacytoid differentiation, often seen in AIDS patients, may demonstrate common morphological characteristics with PEL. In these cases, immunophenotyping usually shows a B-cell lineage in BL compared with the common ‘null’-phenotype of PEL or the rarer T-cell immunophenotype of our case. In addition, the negative staining for both CD10 and Bcl-6 as well as the simultaneous presence of HHV-8, all observed in the present case, did not correlate with the diagnosis of a BL.[64] Finally, pyothorax-associated lymphoma (PAL) is, as the term implies, a pleural EBV-associated NHL that develops after longstanding chronic pleural inflammation. Cytologically, PAL may be indistinguishable from PEL, thus immunophenotyping and HHV-8 testing are essential in this distinction. Indeed, PAL expresses B-cell markers, is HHV-8 negative, and even more it goes hand in hand with the presence of EBV.[6465]

CONCLUSION

All in all, the diagnosis of PEL should be kept in mind whenever lymphomatous effusions, without a detectable primary solid mass, are present and the immunodeficiency status is either evident or is speculated. In such cases, a concrete panel of immunohistochemical markers together with specific molecular studies should be carried out. However, the hallmark of this particular entity remains the identification of HHV-8 infection.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

No competing interest to declare by any of the authors.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT MADE BY ALL AUTHORS

Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved. According to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE http://www.icmje org) an ‘author’ is generally considered to be someone who has made substantive intellectual contributions to a published study. Authorship credit should be based on (1) substantial contribution to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) final approval of the version to be published. Authors should meet conditions (1), (2), and (3). Other contributors, who do not meet these criteria for authorship, are listed in the ‘acknowledgments’ section. All authors of this article declare that they qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE (http://www.icmje.org/#author). Each author has participated sufficiently in the study and takes public responsibility for the appropriate portions of the content of this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is a case report without patient identifiers, approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) is not required at our institution.

EDITORIAL / PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through an automatic online system.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2012/9/1/16/97766

REFERENCES

- Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences are present in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1186-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity associated with the Kaposi's-sarcoma-associated herpes virus. Blood. 1996;88:645-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC Press; 2008. p. :260-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymphomas associated with HIV infection. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC Press; 2008. p. :340-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma: a series of 4 cases and review of the literature with emphasis on cytomorphologic and immunocytochemical differential diagnosis. Cancer. 2007;111:224-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary Effusion Lymphoma in Two HIV-negative patients successfully treated with pleurodesis as first-line therapy. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:271-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary- effusion lymphoma and Kaposi's sarcoma in a cardiac-transplant recipient. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:444-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma after heart transplantation: a new entity associated with human herpesvirus-8. Leukemia. 1999;13:664-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8)-associated primary effusion lymphoma in two renal transplant recipients receiving rapamycin. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:707-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Body cavity-based malignant lymphoma containing Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in an HIV-negative man with previous Kaposi sarcoma. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:822-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human herpes virus-8 associated primary effusion lymphoma of the pleural cavity in HIV-negative elderly men. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:1231-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus / human herpesvirus. Adv Cancer Res. 1999;76:121-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- PEL and HHV8-unrelated effusion lymphomas: classification and diagnosis. Cancer. 2008;114:225-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus DNA sequences in AIDS-related and AIDS-unrelated lymphomatous effusions. Br J Haematol. 1996;94:533-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expression of potentially oncogenic HHV-8 genes in an EBV-negative primary effusion lymphoma occurring in an HIV-seronegative patient. J Pathol. 1999;189:288-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma involving both pleural and abdominal cavities in a patient with hepatitis B virus-related liver cirrhosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106:504-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis C-related primary effusion lymphoma of the pleura and peritoneum, imaged with F-18 FDG PET / CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2010;35:797-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical features and management of malignant ascites. J Pak Med Assoc. 1991;41:38-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytological aspects of pleural, peritoneal and pericardial fluids from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Cytopathology. 1992;3:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma: a liquid phase lymphoma of fluid-filled cavities. Adv Cancer Res. 2001;80:115-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Herpes-like DNA sequences in a body-cavity-based lymphoma in an HIV-negative patient. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:943.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV or HHV8) in primary effusion lymphoma: ultrastructural demonstration of herpesvirus in lymphoma cells. Blood. 1996;87:4937-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expression of human herpesvirus-8 oncogene and cytokine homologues in an HIV-seronegative patient with multicentric Castleman's disease and primary effusion lymphoma. Lab Invest. 1998;78:1637-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pleural effusion as the presentation for primary effusion lymphoma. Surgery. 1998;123:589-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Body-cavity-based lymphoma in an elderly AIDS-unrelated male. Int J Hematol. 1998;67:417-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of body cavity-based lymphoma and human herpesvirus 8 in an HIV-seronegative male.Report of a case with immunocytochemical and molecular studies. Acta Cytol. 1999;43:299-302.

- [Google Scholar]

- Manifestations of three HHV-8-related diseases in an HIV-negative patient: immunoblastic variant multicentric Castleman's disease, primary effusion lymphoma, and Kaposi's sarcoma. Am J Hematol. 2000;65:310-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early peripheral lymph node involvement of human herpesvirus 8-associated, body cavity-based lymphoma in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative patient. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:753-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- CD7 and CD56-positive primary effusion lymphoma in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative host. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;39:633-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody treatment of human herpesvirus 8-associated, body cavity-based lymphoma with an unusual phenotype in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative patient. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:993-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) in HIV-neagtive patients--a distinct clinical entity. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001;41:439-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of primary pleural effusion lymphoma of T-cell origin and human herpesvirus 8 in a human immunodeficiency virus-seronegative man. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:1246-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human herpesvirus 8-associated primary effusion lymphoma in HIV--patients: a clinicopidemiologic variant resembling classic Kaposi's sarcoma. Haematologica. 2002;87:339-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human herpesvirus type 8-associated primary lymphomatous effusion in an elderly HIV-negative patient: clinical and molecular characterization. Ann Ital Med Int. 2002;17:54-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gene expression profile analysis of AIDS-related primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) suggests a plasmablastic derivation and identifies PEL-specific transcripts. Blood. 2003;101:4115-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)-associated peritoneal primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) in two HIV negative elderly patients. Am J Hematol. 2004;76:88-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human herpesvirus 8 in primary effusion lymphoma in an HIV-seronegative male.A case report. Acta Cytol. 2004;48:425-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- A five year follow-up of an HHV-8 related lymphoma in a HIV-negative elderly patient. Clin Ter. 2004;155:543-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of herpesvirus associated primary effusion lymphoma with intracavity cidofovir. Leukemia. 2005;19:473-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- A non-chemotherapy treatment of a primary effusion lymphoma: durable remission after intracavitary cidofovir in HIV negative refractory to chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1849-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic diagnosis of primary effusion lymphoma in a HIV-negative patient. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2008;24:548-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case of HIV-negative primary effusion lymphoma treated with bortezomib, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, and rituximab. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2008;8:300-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intracavitary cidofovir for human herpes virus-8-associated primary effusion lymphoma in an HIV-negative patient. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2010;8:367-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma of T-cell origin with t(7;8)(q32;q13) in an HIV-negative patient with HCV-related liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma positive for HHV6 and HHV8. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:1229-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma in a HIV-negative patient associated with hypogammaglobulinemia. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:777-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chromosomal and comparative genomic analyses of HHV-8-negative primary effusion lymphoma in five HIV-negative Japanese patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43:595-601.

- [Google Scholar]

- An unusual case of posttransplant primary effusion lymphoma with T-cell phenotype in a HIV-negative female, not associated with HHV-8. Pathol Oncol Res. 2005;11:178-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of human herpes virus-8-related primary effusion lymphoma with human herpes virus-8-unrelated primary effusion lymphoma-like lymphoma on the basis of HIV: report of 2 cases and review of 212 cases in the literature. Acta Haematol. 2007;117:132-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human herpes virus 8-unrelated primary effusion lymphoma-like lymphoma: report of a rare case and review of the literature. APMIS. 2009;117:222-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Day L, ed. Atlas of Lymphoid Hyperplasia and Lymphoma (1st ed). Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company; 1997. p. :130-2.

- Distribution of human herpesvirus-8 latenty infected cells in Kaposi's sarcoma, multicentric Castleman's disease, and primary effusion lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4546-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunoglobulin VH gene mutational analysis suggests that primary effusion lymphomas derive from different stages of B cell maturation. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1609-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunoglobulin V region gene use and structure suggest antigen selection in AIDS-related primary effusion lymphomas. Leukemia. 1999;13:1093-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-positive primary effusion lymphoma with expression of the CD138 / syndecan-1 antigen. Blood. 1997;90:4894-900.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expression profile of MUM1 / IRF4, BCL-6, and CD138 / syndecan-1 defines novel histogenetic subsets of human immunodeficiency virus-related lymphomas. Blood. 2001;97:744-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Herpesvirus 8 Inclusions in primary effusion lymphoma. report of a unique case with T-cell phenotype. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:257-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- A clinical, molecular and cytogenetic study of 12 cases of human herpesvirus 8 associated primary effusion lymphoma in HIV-infected patients. Hematol J. 2001;2:172-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anaplastic large cell lymphoma presenting as a pleural effusion and mimicking primary effusion lymphoma.A report of 2 cases. Acta Cytol. 2003;47:809-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma: a series of 4 cases and review of the literature with emphasis on cytomorphologic and immunocytochemical differential diagnosis. Cancer. 2007;111:224-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pyothorax-associated lymphoma: a review of 106 cases. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4255-60.

- [Google Scholar]