Translate this page into:

Clinical evaluation, imaging studies, indications for cytologic study and preprocedural requirements for duct brushing studies and pancreatic fine-needle aspiration: The Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology Guidelines

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

The Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology has developed a set of guidelines for pancreaticobiliary cytology including indications for endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy, techniques for EUS-FNA, terminology and nomenclature to be used for pancreaticobiliary disease, ancillary testing and postbiopsy management. All documents are based on expertise of the authors, literature review, discussions of the draft document at national and international meetings and synthesis of online comments of the draft document. This document selectively presents the results of these discussions. This document summarizes recommendations for the clinical and imaging work-up of pancreatic and biliary tract lesions along with indications for cytologic study of these lesions. Prebrushing and FNA requirements are also discussed.

Keywords

Bile duct

cytology

fine-needle aspiration

guidelines

indications

pancreas

primary sclerosing cholangitis

INTRODUCTION

The workup of a biliary stricture, pancreatic cyst or solid mass requires a carefully orchestrated sequence of clinical and imaging studies which may be followed by cytologic investigation. The current document describes the clinical work-up along with imaging studies as recommended by the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology. Recommendations are made for the appropriate use of bile duct brushing cytology obtained via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology of mass lesions in the pancreas. Prebrushing and FNA requirements are discussed including consent forms and information to be included in the requisition form for optimal cytologic evaluation of pancreatic and biliary tract specimens.

PRESENTATION AND CLINICAL EVALUATION

A variety of clinical and laboratory features are associated with malignancy of the biliary tract or pancreas. Newly diagnosed late onset diabetes mellitus or unexplained acute pancreatitis in an older individual require workup, which often includes exclusion of pancreatic carcinoma.[1] Similarly, the development of jaundice, pruritus or cholestasis not explained by underlying liver or gallbladder disease or choledocholithiasis should initiate an evaluation for neoplasia of the hepaticobiliary tract.[123] In addition to the above, clinical investigation and imaging studies may be initiated for a variety of reasons including abdominal pain that radiates to the back, anorexia, weight loss, new onset diabetes, steatorrhea, the presence of newly discovered metastatic disease or abnormal liver enzymes. Laboratory and imaging studies play an important role in the evaluation of patients with pancreaticobiliary lesions.

Patients with suspected neoplasia of the pancreaticobiliary tract should receive:

-

A thorough history and physical examination including identifying risk factors for malignant causes and for benign explanations for a stricture or cyst (e.g., chronic pancreatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)/inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), autoimmune disease, etc.)

-

Laboratory studies to detect elevations of serum bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase as well as other liver chemistries

-

Selective use of serum tumor markers including CA19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)[456]

-

Imaging studies

-

Selective use of serum IgG4 when autoimmune diseases are suspected.

IMAGING STUDIES

Imaging modalities used in evaluating patients with clinically suspected pancreaticobiliary neoplasia include abdominal ultrasound (AUS) selective use of computerized tomography (CT), ERCP, EUS, and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). When used, MRI may include MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and occasionally, MR angiography (MRA).[123] Positron emission tomography-CT is recommended for staging pancreatic cancer if curative surgery is contemplated. It is not currently recommended for diagnosis.

AUS is the least invasive and lowest-cost imaging technique available for evaluation of obstructive jaundice and biliary obstruction by demonstration of biliary duct dilatation when taking into consideration the patient's age and history of prior cholecystectomy (both of which can affect ductal diameter). It may also disclose obvious liver metastases. transcutaneous ultrasound (TUS) is operator dependent and has a relatively poor sensitivity for detecting small neoplasms within the pancreatic head.[23] TUS can only see the pancreas in a limited manner, usually due to intervening ultrasound-attenuating abdominal wall fat, the depth of penetration to see the retroperitoneum and/or overlapping gas-filled stomach or loops of bowel. Recent advances in ultrasound technology including color power Doppler ultrasonography, ultrasonographic angiography, contrast harmonic imaging and three-dimensional ultrasonography may improve the sensitivity and specificity of the ultrasound technique.[78910111213]

Multi-phase CT scanning of the abdomen utilizing fine cuts through the pancreas with contrast enhancement (“pancreas protocol” CT scanning) is more sensitive and specific than AUS for detecting biliary obstruction, and has the ability to determine the site and cause of obstruction. CT is strongly recommended as the primary modality for evaluating patients with suspected malignant biliary obstruction, both for diagnosis and for staging. It also allows detection of liver metastases and invasion of vascular structures as well as potential lymph node involvement.[1415161718192021222324] Multidetector CT (MDCT) may improve accuracy above that obtainable by helical CT. New CT techniques may further increase the sensitivity of CT for pancreatic neoplasia.[25262728] MDCT relies heavily on hypoperfusion seen in many adenocarcinomas, and mass effect. Several studies have more recently shown that smaller lesions, on well-perfused tumors can have a modest miss-rate with CT.

If CT findings are consistent with resectable pancreatic carcinoma and the patient is felt to be otherwise an operative candidate, the patient may be referred directly for surgery without further imaging or diagnostic testing, although this clinical situation is rarely encountered. In addition, this approach risks inappropriate surgery for focal pancreatitis (including autoimmune pancreatitis) or lymphoma. Transabdominal or CT guided biopsy of the pancreatic mass may be requested when endoscopic techniques are not readily available, but had a lower performance in a randomized trial.[45]

When CT scanning reveals definitive evidence of unresectability for pancreatic or biliary tract cancer or if the patient is either a non-operative candidate due to comorbidities or in cases where surgery is planned but delayed (i.e., in patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy, patients needing more involved evaluation and/or stabilization of other medical issues, etc.), the placement of a biliary stent is typically performed through ERCP for palliation, or to reduce cholestasis to allow adjuvant therapy.

In recent times, neoadjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation are being utilized in potentially resectable or borderline resectable patients and usually requires a definitive preoperative tissue diagnosis. Transabdominal CT or ultrasound biopsy of metastatic disease may be sufficient; in nonmetastatic disease, EUS-guided FNA is a higher yield maneuver and may be obtained of either the primary site or a metastatic site reachable with EUS. EUS is now the procedure of choice for evaluating and sampling pancreatic masses at many institutions.

Multiple MRI techniques exist for evaluation of the pancreas for neoplastic disease. These include MRI, MRCP, or MRA. Traditional abdominal MRI appears to be a highly accurate modality for staging pancreatic carcinoma but does not appear to be more specific or sensitive than CT.[293031] Modifications of the MRI technique such as MRCP and MRA may improve sensitivity and specificity and may be useful for vascatar staging.[32333435] MRCP provides much better ductal imaging, illustrating the level and cause of the obstruction more reliably than CT, but in determination of benign versus malignant strictures it has weaker performance. It is also more reliable than CT at differentiating solid versus cystic lesions in the pancreas and determining morphology of the cyst and communication with the pancreatic duct. It is weaker at detecting calcifications than CT, which may point to a benign explanation for the stricture or cyst.

DIAGNOSTIC WORK-UP FOR CYSTS OF THE PANCREAS

The most important determination in the investigation of a pancreatic cyst is whether the cyst is mucinous (premalignant) or nonmucinous (serous, developmental and inflammatory).

This distinction by preoperative imaging has been disappointing, but imaging classification systems have been proposed.[36] Small incidental cysts can usually be managed expectantly.[37] Serous cystadenomas may have characteristic imaging and clinical features allowing their recognition without further investigation.[38] Such neoplasms demonstrate a microcystic "honeycomb" appearance with a central scar. CT scans are frequently the first test used to evaluate a pancreatic cyst. Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography and EUS can be used if further evaluation is deemed necessary.[38]

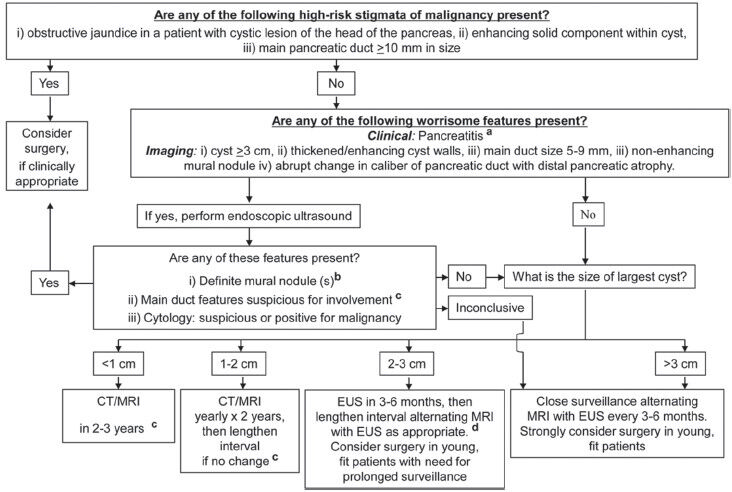

A multidisciplinary conference held at Sendai, Japan in 2005 led to published guidelines in 2006 (the "Sendai guidelines"), which established algorithmic protocols for the workup and management of patients with pancreatic neoplastic mucinous cysts.[3940] These guidelines were updated in 2010, and published in 2012 (the 2012 guidelines)[41] [Figure 1]. The guidelines base management primarily on clinical and imaging findings with conservative management of small cysts (<3 cm) occurring in patients without high-risk clinical or imaging findings.

- Reprinted from pancreatology, published online 02 May 2012, Tanaka M, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Adsay V, Chari S, Falconi M, Jang J, Kimura W, Levy P, Pitman M, Schmidt CM, Shimizu M, Wolfgang C, Yamaguchi K, Yamao K, International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas, copyright 2012, with permission from Elsevier

Patients considered at high-risk for malignancy are those with obstructive jaundice and a cystic lesion in the head of the pancreas, an enhancing solid component within the cyst or a main pancreatic duct ≥10 mm in diameter. These patients are triaged to surgery without preoperative tissue confirmation. If these high-risk features are absent, the patient should be further evaluated for the presence of pancreatitis or worrisome imaging features.

Worrisome imaging features warranting endoscopic ultrasound and consideration of biopsy include a cyst equal to or >3 cm in diameter, thickened/enhancing cyst wall, a main pancreatic duct 5-9 mm in diameter, a nonenhancing mural nodule, or an abrupt change in the caliber of the main pancreatic duct with distal pancreatic atrophy. Patients with pancreatitis should also be referred for endoscopy. When EUS discloses a definitive mural nodule, a main duct with features suspicious for involvement by the cystic lesion or cytology suspicious or positive for malignancy, the patient should be referred for surgery.

In the absence of high-risk and worrisome features, further management depends on the size of the cystic lesion. Cysts under 1 cm in size should undergo CT/MRI re-examination in 2-3 years. Cysts between 1 and 2 cm in size should have yearly CT/MRI examinations for 2 consecutive years if no significant change is noted, the interval can be lengthened. Patients with cysts between 2 and 3 cm in maximum dimension should undergo EUS examination in 3-6 months. Then have repeat MRI examinations at lengthened intervals alternating with EUS as appropriate. Young fit patients may be considered for surgery. Patients whose cysts are over 3 cm in size should undergo repeat MRI examinations alternating with EUS every 3-6 months. Surgery should be strongly considered as an alternative strategy in young fit patients.

ENDOSCOPIC DIAGNOSTIC TECHNIQUES

When EUS is available, it should be used for preoperative staging in patients with suspected pancreatic carcinoma or cancer of the biliary tract. In addition, in low to moderate suspicion cases (dilated ducts or unexplained weight loss), it has high negative predictive value. EUS is particularly useful when CT or MR findings are equivocal, in CT-resectable disease to screen for subtle vascular involvement (especially in borderline surgical candidates), or when unresectable disease is suspected and a tissue diagnosis is needed.[42] EUS demonstrates significant advantages over CT and MR in establishing the presence of vascular invasion.[43444546] EUS appears to be complementary to CT, but EUS appears to be superior for detecting small masses, evaluating for tumor involvement of the superior mesenteric vein and the portal vein and detecting lymph node metastases.[43444546] The overall staging accuracy of EUS for pancreatic adenocarcinoma is between 90% and 100%. When compared with CT in this population, EUS has a higher sensitivity for tumor detection. For small (<16 mm) pancreatic masses, the sensitivity of EUS for tumor detection approaches 100%, compared with 66% using MDCT. Accuracy for resectability, as determined by EUS, is 88-100%.[4445] CT appears superior to EUS when evaluating the SMA as EUS can only see this vessel for a short distance beyond its origin, and for establishing the presence of absence of distant metastases.[43444546] Adjuncts to EUS, such as elastography and contrast harmonic imaging, are promising to improve performance in selected cases.

A key advantage of EUS is that EUS-guided FNA can be performed as an integral part of EUS examination. This allows definitive tissue acquisition and rapid diagnosis. When EUS suggests resectability, EUS-guided biopsy may not be necessary prior to definitive resection. However, in many institutions all solid pancreatic masses are aspirated prior to surgery (to rule out lymphoma, autoimmune/focal pancreatitis and assess for other types of cancer beyond adenocarcinoma). The requirement for tissue diagnosis in this setting remains controversial. FNA of the mass does have some advantages in that it may establish diagnoses other than primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma and allows for preoperative patient counseling. Many patients in the current era also undergo neoadjuvant therapy preoperatively as well and in general, most medical and radiation oncologists will not treat a patient without a definitive tissue diagnosis. It should be kept in mind that preoperative EUS-guided FNA, while overwhelmingly safe and effective, has a small risk of complications including pancreatitis, infection of upstream obstructed ducts and hemorrhage. The potential for needle track tumor implantation is felt to be extremely small, but still possible and essentially restricted to the body and tail masses sampled with transgastric FNA (since the needle tracks site is resected when transduodenal FNA is followed by a Whipple).[47]

The evaluation of cystic lesions of the pancreas has historically been a clinical challenge. It is often difficult to identify the type of cystic lesion present based on cross-sectional imaging alone. Furthermore, CT is not particularly helpful in the assessment of the potential malignant character of cysts. MRCP is more helpful at determining the presence of solid components and ductal communication suspicious of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, but small solid components, calcifications and septations may be missed. Some lesions, such as serous cystadenomas, may have a typical appearance that can be identified on cross sectional imaging, but in most cases, further evaluation is needed.

In recent years, it has become clear that cyst fluid analysis may be more helpful than imaging morphology in many cases. Due to the difficulty in assessment of cystic lesions by cross sectional imaging and the ease with which pancreatic cyst fluid can be obtained via EUS, the threshold for cyst aspiration by EUS is very low. While cystic lesions as small as 5-6 mm can be successfully aspirated under EUS, most endoscopists do not perform FNA for cystic lesions under 1-1.5 cm due to the limited amount of fluid/cellular material available for analysis. Cysts >1-1.5 cm in size are commonly aspirated.[48] The above criteria apply in the absence of pancreatitis.

A prior history of pancreatitis may or may not prompt a cyst evaluation if there is a strong suspicion that a cystic lesion is a pseudocyst (especially if antecedent imaging obtained before the episode of pancreatitis failed to show the lesion) the lesions may be followed by serial imaging. Pseudocysts obviously arising in acute pancreatitis are not generally aspirated, for many reasons, including low-yield of finding another diagnosis, high overlap of CA19-9 in pseudocysts versus mucinous lesions, and the higher chance of infection in the presence of thick fluid, debris, and necrosis. If there is concern that a cystic lesion may have led to an episode of pancreatitis, EUS with FNA is often warranted.

While all care should be individualized, worrisome signs on EUS of cystic lesions include a size >2 cm, intracystic nodularity or an associated solid component or thick wall. Pain, pancreatic duct dilatation, jaundice and weight loss also may increase the chance of a malignant cause, although many of these features can be present in chronic pancreatitis. Thus, patients presenting with cystic lesions larger than 2 cm, especially without a history of pancreatitis, pancreatic or bile duct enlargement and/or weight loss should be strongly considered for EUS with FNA.[4849]

ENDOSCOPIC RETROGRADE CHOLANGIOPANCREATOGRAPHY

Although years ago, ERCP was felt to be a gold standard for cystic lesions of the pancreas, and evaluation of biliary strictures or a "double duct sign", EUS and MRCP have replaced it for many of these indications, avoiding its risks, particularly pancreatitis, and infection of cysts with contrast. It is now only rarely used as a primary tool for establishing the diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma or workup of pancreatic cysts. Currently, ERCP is the most useful clinically for providing relief of obstructive jaundice by either plastic or metal biliary stent placement. Brush cytology (mono-sampling) from biliary strictures or, to a lesser extent, pancreatic duct strictures, is still widely performed but has a much lower yield than EUS FNA.

DIAGNOSTIC TECHNIQUES FOR SUSPECTED CHOLANGIOCARCINOMA

EUS has not been shown to be superior to other imaging and sampling techniques for identification of cholangiocarcinoma. EUS identification of cholangiocarcinoma is often technically difficult even for experienced endosonographers, for many reasons. Early cholangiocarcinoma can be laterally spreading along the duct, with minimal "mass" or wall thickening. FNA of a thin-walled mass has low yield. Sizable tumors at the hilum have good yield with trans-bulb FNA of either the mass or periportal lymph nodes. Tumors above the hilum are not generally evaluable with EUS.[50] Intraductal ultrasonography performed at the time of ERCP may add additional information in patients suspected of pancreaticobiliary malignancies especially cholangiocarcinomas, but performance characteristics and accuracy for benign versus malignant strictures appear poor.

POSTIMAGING STUDIES

Following studies establishing imaging diagnosis of pancreatic and/or pancreaticobiliary malignancy, some clinicians may desire tissue confirmation. Such tissue confirmation can be performed by either abdominal CT or ultrasound-guided FNA, ERCP-guided bile duct or pancreatic duct brushings or EUS-guided FNA.[50] The value and clinical necessity of such biopsies remains controversial. In the majority of cases, these techniques are easily performed, but have variable degrees of sensitivity and specificity as discussed in the section on diagnostic criteria. Size, criteria and location criteria for the utilization of image-guided biopsy techniques are controversial, but EUS has become the dominant technique for evaluating and performing a biopsy on known or suspected pancreatic masses. Most pancreatic neoplasms are adenocarcinoma, but the differential diagnosis includes pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, autoimmune pancreatitis, and metastatic disease (among other causes). Given the need for tissue diagnosis prior to neoadjuvant or palliative chemotherapy, FNA is almost always performed for solid pancreatic tumors. Biopsy is most commonly performed through EUS guidance or CT guidance. EUS FNA has similar, and possibly superior, sensitivity to CT guided FNA.[51] There is also the possibility of an increased risk of peritoneal carcinomatosis by tumor seeding using the percutaneous approach (which may be reduced through EUS guided FNA).[52] The use of EUS in staging pancreatic cancer allows for identification of resectability and FNA in the same procedure. EUS diagnosis of pancreatic masses can be limited in the setting of recent acute pancreatitis (<4 weeks), chronic pancreatitis, a prominent ventral/dorsal split of the pancreatic head, or in diffusely infiltrating cancer (all of which distort the underlying parenchyma, which EUS relies upon to see abnormal masses through contrast between the two).[53]

Techniques for the workup of solid and cystic lesions of the pancreas vary. Cysts should be aspirated with as much fluid being drawn off as possible and sent for cytologic, chemical and molecular analysis; CEA appears to be the most helpful and would be the priority when limited fluid is obtained. Multiple FNAs of solid lesions should be obtained if immediate on-site cytologic evaluation is not available. If an on-site cytopathologic evaluation is available, then intraprocedural cytologic evaluation should be performed to insure adequacy of tissue samples.

PRE-FNA REQUIREMENTS

Informed consent form for pancreaticobiliary FNA

Informed consent is the communication process between the patient and the physician that results in the patient's agreement to undergo a particular procedure and/or treatment.[54555657585960] The principle of informed consent is a legal principle and based on the belief that a competent individual has the right to determine what is done to her or him.[54555657585960] All medical care including the procuring of laboratory tests requires at least informal informed consent except when a patient is incompetent to make decisions or has abrogated that right.[54555657585960] Legislation regulating conditions under which informed consent must be obtained vary from state to state.[545859] Due to this variability, providers including pathologists, radiologists, endoscopists and surgeons need to be familiar with the informed consent policies based on state regulations. The AMA recommends that the following be disclosed and discussed with the patient:

-

The patient's diagnosis, if known

-

The nature and purpose of the proposed treatment or procedure

-

The risks and benefits of a proposed treatment or procedure

-

Alternate options

-

The risk and benefits of the alternate treatment or procedure

-

The risks and benefits of not receiving or undergoing the treatment or procedure.

Unfortunately, informed consent procedures are imperfect.[5455] Less than half of the population understands commonly utilized medical terms which limits the value to the patient of many informed consents. It is often not feasible to discuss all alternate options in the limited time available in the preprocedure setting, especially in the era of open-access radiology and open-access endoscopy.[6162636465] The use of written information supplied during the informed consent procedure may increase patient comprehension.[66676869] No matter what form informed consent takes, it must be clearly understood by the patient and adequate opportunity for patient questions must be available.[69]

Informed consent recommendations

-

Use of informed consent materials including written documents describing the FNA procedure and potential risks and complications may be considered

-

The possibility of bleeding, allergic/cardiac/respiratory reaction, hemorrhage, and/or perforation should be mentioned

-

Information should be presented in a manner to facilitate patient understanding

-

Informed consent should include telling the patient that the results may be non-contributory (unhelpful)

-

Estimates of accuracy such as false negative or false positive rates are not mandatory and should be discussed only if the practitioner believes that they would facilitate patient comprehension.

INFORMATION REQUIRED ON THE REQUISITION FORM THAT ACCOMPANIES A PANCREATIC FNA REQUEST

Federal regulations in the United States require that certain identifying information be provided to laboratories with all specimens submitted for laboratory testing.[70] These requirements include:

-

Name and address of person requesting the test

-

Patient's name and/or unique identifier

-

Patient gender

-

Patient age or date of birth

-

Name of the test to be performed

-

Specimen source and location, i.e., "head of pancreas"

-

Date of specimen collection

-

Any additional relevant information (This request is usually construed to mean clinical history).

Additional relevant information which when included is helpful for specimen evaluation should be conveyed to the pathologist in the clinical or additional information section. This information may include precise site of the lesion being sampled, the tissue traversed in FNA (transgastric, transduodenal, etc.), the presence or absence of bile duct or pancreatic duct stricture, and the size of the lesion. The solid or cystic nature of the lesion should also be included in the clinical history. In cystic lesions, the configuration of the cyst, whether single or multilocular is helpful for pathologic examination. Similarly, the ultrasonographic, CT or MR characteristics of the lesion should be included as additional information, including presence of vascular or other organ invasion or known metastatic disease. History of prior malignancy should be included, as well as history of alternative diagnoses (alcoholic abuse, pancreatitis, PSC/IBD, autoimmune disease) if relevant. The occurrence of recent pancreatitis or cholangitis, and presence of a stent should also be included with relevant history, as inflammation or stent-induced atypia may need to be taken into consideration. Clinical suspicion of neuroendocrine tumor or lymphoma should be indicated, as it requires special stains/media.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article. Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, general manuscripts undergo a double blind peer review process (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system. However, the current article is part of guidelines by Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology (PSC) submitted by the committee members as authors and is being published after due copy-editing without peer review. Because it is agreed to be published as Open Access article under Creative Commons Legal Code (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/), this intellectual property (IP) would be retained in public domain.

REFERENCES

- Pancreatric Section, British Society of Gastroenterology, Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland, Royal College of Pathologists, Special Interest Group for Gastro-Intestinal Radiology. Guidelines for the management of patients with pancreatic cancer periampullary and ampullary carcinomas. Gut. 2005;54(Suppl 5):v1-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of endoscopy in the evaluation and treatment of patients with pancreaticobiliary malignancy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:643-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of endoscopy in the evaluation and treatment of patients with pancreaticobiliary malignancy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:643-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The utility of CA 19-9 in the diagnoses of cholangiocarcinoma in patients without primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:204-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detecting cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:40-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of the sensitivity and specificity of the CA19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen assays in detecting cancer of the pancreas. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:343-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gray-scale ultrasonography and endoscopic pancreatography in pancreatic diagnosis. Radiology. 1980;134:453-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasonographic scanning of the pancreas. Prospective study of clinical results. Radiology. 1981;138:211-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abdominal US for diagnosis of pancreatic tumor: Prospective cohort analysis. Radiology. 1999;213:107-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting image quality and diagnostic efficacy in abdominal sonography: A prospective study of 140 patients. J Clin Ultrasound. 1993;21:623-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of arterial invasion in pancreatic cancer using color Doppler ultrasonography. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1410-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Imaging of pancreatic neoplasms: Comparison of MR and CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:487-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic ducts: Comparative evaluation with CT and MR imaging at 1.5 T. Radiology. 1992;183:87-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dual-phase helical CT of the liver: Value of arterial phase scans in the detection of small (< or=1.5 cm) malignant hepatic neoplasms. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:879-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Diagnosis and staging with dynamic CT. Radiology. 1988;166:125-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and staging of pancreatic adenocarcinoma with dynamic computed tomography. Am J Surg. 1993;165:600-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thin-section contrast-enhanced computed tomography accurately predicts the resectability of malignant pancreatic neoplasms. Am J Surg. 1994;167:104-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Relative value of arterial and late phases of spiral CT. Abdom Imaging. 1997;22:199-203.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pancreatic arterial anatomy: Depiction with dual-phase helical CT. Radiology. 1998;208:537-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of resectability of pancreatic malignancy by computed tomography. Br J Surg. 1998;85:320-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Three-dimensional CT angiography of pancreatic carcinoma: Role in staging extent of disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:139-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of three-dimensional spiral computed tomographic angiography to pancreatoduodenectomy for cancer. Br J Surg. 1995;82:116-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spiral CT and the pre-operative assessment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Clin Radiol. 1997;52:24-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Small peripancreatic veins: Improved assessment in pancreatic cancer patients using thin-section pancreatic phase helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:377-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: CT versus MR imaging in the evaluation of resectability: Report of the Radiology Diagnostic Oncology Group. Radiology. 1995;195:327-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Preoperative assessment with helical CT versus dynamic MR imaging. Radiology. 1997;202:655-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abdominal diffusion mapping with use of a whole-body echo-planar system. Radiology. 1994;190:475-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging of the portal venous system: Comparison with x-ray angiography. Radiology. 1994;191:741-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Imaging findings of pancreaticobiliary duct diseases with single-shot MR cholangiopancreatography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:453-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- MR cholangiopancreatography of bile and pancreatic duct abnormalities with emphasis on the single-shot fast spin-echo technique. Radiographics. 2000;20:939-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cystic pancreatic lesions: A simple imaging-based classification system for guiding management. Radiographics. 2005;25:1471-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- ACG practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2339-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pancreatic cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v55-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6:17-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis and staging of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Results of a prospective study with comparison to ultrasonography and CT scan. Endoscopy. 1993;25:143-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Value of helical computed tomography, angiography, and endoscopic ultrasound in determining resectability of periampullary carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1997;174:237-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pancreatic tumors: Comparison of dual-phase helical CT and endoscopic sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1315-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Correlation between spiral computed tomography, endoscopic ultrasonography and findings at operation in pancreatic and ampullary tumours. Br J Surg. 1999;86:189-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- EUS, PET, and CT scanning for evaluation of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:367-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adverse events associated with EUS and EUS with FNA. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:839-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and treatment of cystic pancreatic tumors. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:635-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cyst features and risk of malignancy in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: A meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:913-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of suspected cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:209-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- A randomized comparison of EUS-guided FNA versus CT or US-guided FNA for the evaluation of pancreatic mass lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:966-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lower frequency of peritoneal carcinomatosis in patients with pancreatic cancer diagnosed by EUS-guided FNA vs. percutaneous FNA. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:690-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The No Endosonographic Detection of Tumor (NEST) Study: A case series of pancreatic cancers missed on endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 2004;36:385-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 43; AHRQ Publication 01-E058. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2001.

- [Google Scholar]

- Procedures for obtaining informed consent. Ch. 48. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/clia/pdf/42cfr493_2003.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Informed decision making in outpatient practice: Time to get back to basics. JAMA. 1999;282:2313-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Procedures for obtaining informed consent. In: Shojania K, Duncan B, McDonald K, Wachter RM, eds. Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. Volume AHRQ Publication 01-E058. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2001. p. :546-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- iMed Consent. The standard of care for informed consent. Available from: http://www.dialogmedical.com/ic.htm

- [Google Scholar]

- Informed Consent: American Medical Association. Available from: http://www.ana-assn.org/ama/pub/category/4608.html

- [Google Scholar]

- Informed Consent: Legal Theory and Clinical Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001.

- [Google Scholar]

- Informed consent forms for clinical and research imaging procedures: How much do patients understand? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:493-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reading versus comprehension: Implications for patient education and consent in an outpatient oncology clinic. J Cancer Educ. 1994;9:26-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Difference between patients’ and doctors’ interpretation of some common medical terms. Br Med J. 1970;2:286-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Informed consent: The assessment of two structured interview approaches compared to the current approach. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106:420-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- A typology of shared decision making, informed consent, and simple consent. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:54-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hospital informed consent for procedure forms: Facilitating quality patient-physician interaction. Arch Surg. 2000;135:26-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:520-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Veterans Health Administration. VHA informed consent for clinical treatments and procedures. In: VHA Handbook. Vol 1004. Washington DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration; 2003.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: A review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Federal Register. P Laboratory Requirements; 2007 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/clia/pdf/42cfr493_2003.pdf

- [Google Scholar]