Translate this page into:

Cokeromyces recurvatus in a Papanicolaou test: An exceedingly rare finding that can be mistaken for Paracoccidioides brasiliensis

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Cokeromyces recurvatus is a zygomycetes yeast form that is very rarely detected in Papanicolaou (Pap) tests, in which it typically represents an innocuous colonizer. Its morphology closely resembles that of the better known Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, which can disseminate widely and cause clinically significant disease. We present a case of C. recurvatus detected in a cervical liquid-based preparation obtained from a 38-year old healthy woman. Careful cytomorphologic evaluation, in combination with culture and molecular techniques, was utilized to make a diagnosis and prevent the misdiagnosis of P. brasiliensis.

Keywords

Cokeromyces recurvatus

liquid-based preparations

Paracoccidioides brasiliensis

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy gravida 4 para 2, 38-year-old Caucasian woman presented with the acute onset of pelvic pain. The physical examination was unremarkable. A transvaginal ultrasound revealed a heterogeneous area in the left ovary related to a corpus luteal cyst. The previous Papanicolaou (Pap) test results had been negative. She had no history of travel or animal exposure and was not on immunosuppressive or antifungal therapy. A cervical cytologic sample was obtained.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Liquid-based preparations (LBP) (ThinPrep, Hologic, Inc, Marlborough, Massachusetts) Papanicolaou tests were evaluated. A Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stain was performed on an LBP. A vaginal culture taken following the initial Pap test was plated on Sabouraud's dextrose agar. The residual sample was sent for broad-spectrum polymerase chain amplification, targeting the fungal internal transcribed spacer region (ITS), and subsequent sequence homology analysis of the amplification product, utilizing the public NCBI database.

RESULTS

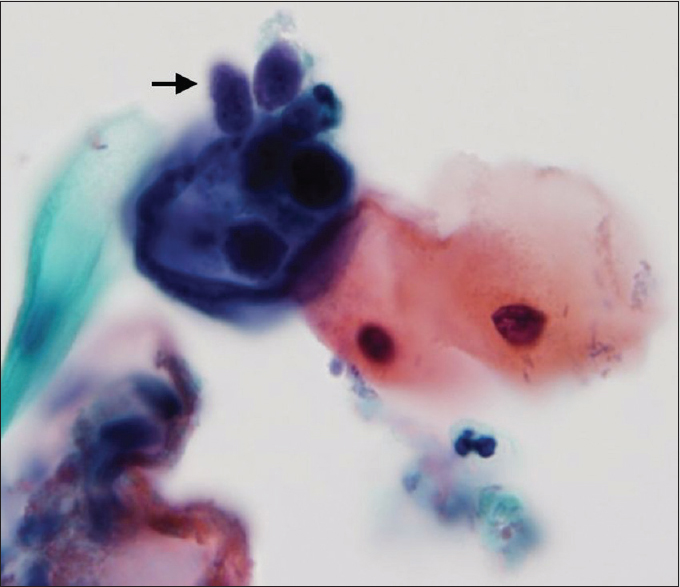

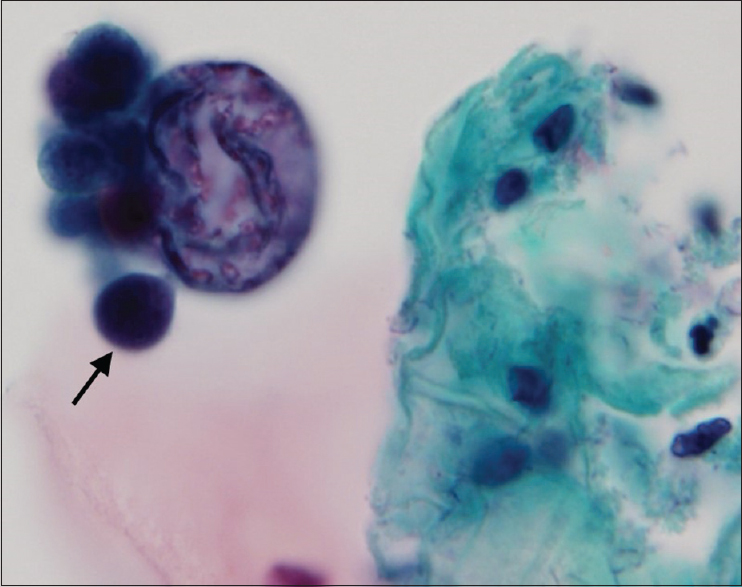

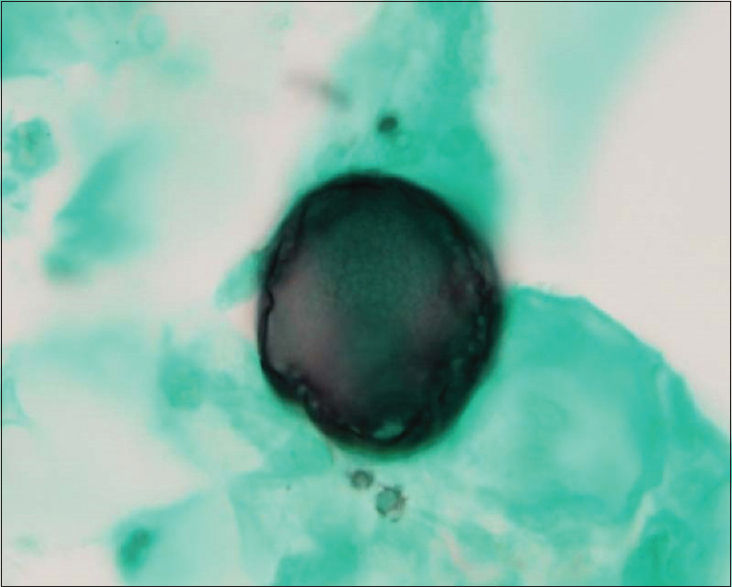

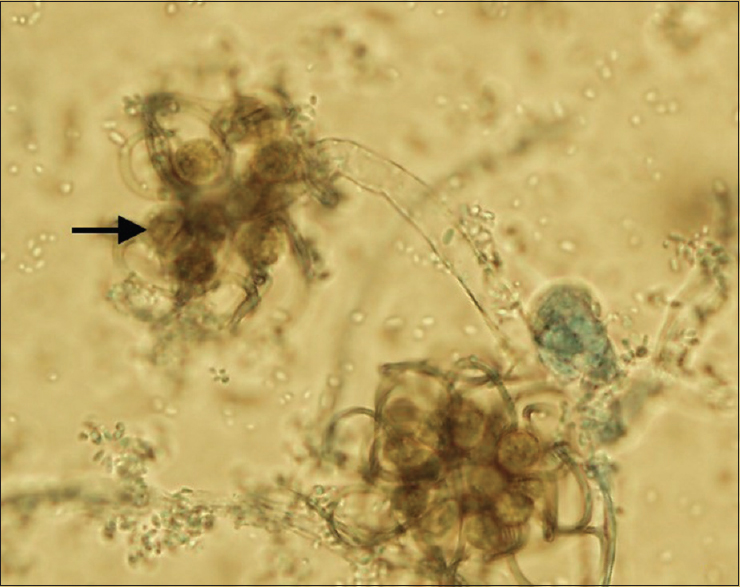

The LBP showed globose, yeast-like forms 28–30 micrometers in diameter. Several had multiple narrowly attached rounded “daughter” buds 5–6 micrometers in diameter, arrayed partially around the central cell [Figures 1 and 2]. The background consisted of benign squamous epithelial cells with reparative changes and mild inflammation. On preliminary evaluation, the yeast-like forms were thought to be contaminants, but a literature search suggested the possibility of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis or Cokeromyces as described in the case report by Odronic et al.[1] The subsequent GMS stain highlighted the fungal yeast forms [Figure 3].

- Liquid-based cervical sample: Cokeromyces recurvatus showing yeast forms with multiple rounded daughter buds (arrow). (ThinPrep, Papanicolaou stain, ×100)

- Liquid-based cervical sample: Cokeromyces recurvatus showing “daughter” buds (arrow) arrayed partially around the center cell (ThinPrep, Papincolaou, ×100)

- Liquid-based cervical sample: Cokeromyces recurvatus rounded yeast forms (Gomori methenamine silver stain, ×100)

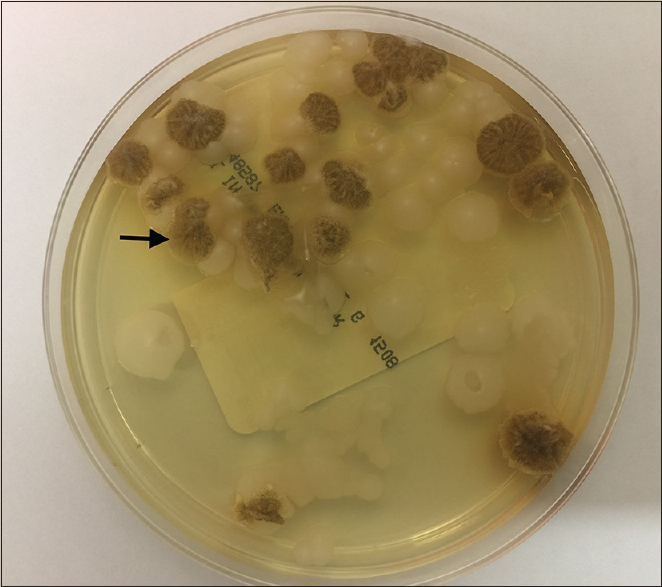

Fungal cultures grew light brown mold colonies on Sabouraud's dextrose agar [Figure 4]. Hyaline, smooth-walled, broad hyphae developed sporangiophores, each terminating in a large spherical vesicle, after 1–2 days of incubation at 27°C. Arising from the vesicles were elongate, recurved stalks or pedicles, each bearing globose sporangia [Figure 5].

- Multiple light brown mold (arrow) colonies on Sabouraud's dextrose agar at 27°C

- Sporangiola (arrow) produced at the tips of recurved or twisted stalks on a vesicle of a sporangiophore (×100)

Polymerase chain reaction amplification of a 483 base-pair fragment from the ITS of the 18S ribosomal RNA gene produced a 99.8% match with Cokeromyces recurvatus isolate AFTOL-ID 627 (sequence ID AY997040.1) and CBS 158.50 (sequence ID JN206244.1). Based on the cytologic appearance, colony morphology, and molecular testing results, the mold was identified as C. recurvatus.

DISCUSSION

C. recurvatus is a dimorphic fungus belonging to the family Thamnidiaceae in the order Mucorales of the class Zygomycetes.[2] Its geographic distribution includes Mexico and the United States; isolates have been detected in California, Arizona, Illinois, Michigan, and Florida.[2] The differential diagnosis for large spherical forms with single or multiple budding forms includes P. brasiliensis, giant blastoconidia of Candida albicans, and spherules of Coccidioides immitis. The morphology of C. recurvatus most closely resembles that of P. brasiliensis, which is distributed in Brazil and South America and can disseminate and cause clinical disease. Paracoccidioides have large fungal-like elements with a distinct budding pattern characterized by symmetrically arranged multiple narrow buds resembling a “Mariner's wheel,” which looks similar to C. recurvatus, though C. recurvatus has asymmetrically arranged buds and occurs outside the epidemiological distribution of P. brasiliensis. P. brasiliensis grows very slowly (2–3 weeks) at room temperature and sporulation is poor, whereas C. recurvatus grows faster and produces sporangiospores and zygospores (3–6 days). At 37°C, the conversion to yeast phase is easily obtained with C. recurvatus, but it takes 10–20 days on blood cysteine agar for P. brasiliensis.[3] P. brasiliensis has been identified in cervical samples of two young asymptomatic women.[45] The cytomorphology of the fungi was very similar to those in the present case, and none of the cases underwent confirmatory culture or molecular testing.

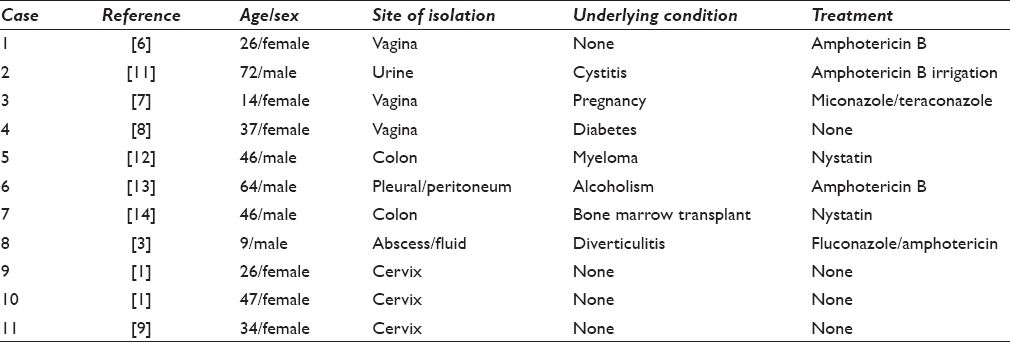

There have been 11 prior cases of C. recurvatus reported in the literature [Table 1].[11121314] The vagina and cervix have been the most common sites from which C. recurvatus has been isolated in humans, with six cases being reported from Pap tests.[16789] In all reports of C. recurvatus from gynecologic specimens, there was the only evidence of colonization. In the nongynecologic sites, the cases represent a mix of invasive and colonizing fungus with severe immunosuppression correlating with the risk of invasion.

Zygomycosis has also been reported to also affect animals living in temperate, tropical, and subtropical climates, and these diseases are often fatal.[10]

While there has been one prior report of using molecular tests for confirming the diagnosis of C. recurvatus,[1] we believe our case is the first to include cytology, cultures, and molecular testing to categorize this unusual fungus.

In summary, the identification of C. recurvatus in a Pap test can be problematic as the organism is rarely encountered and can be dismissed as a contaminant or misinterpreted as P. brasiliensis, a fungus that is an even rarer finding in the Pap tests. Careful cytomorphology, along with fungal cultures and molecular testing, can confirm a diagnosis of C. recurvatus.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

“The authors declare that they have no competing interests

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article. NS performed the literature review, participated in study data acquisition, coordinated the study completion and drafted the manuscript. XL conceived the study, participated in the design, critically reviewed the draft and is the corresponding author. EG and JM performed a critical review of the manuscript and helped to draft the manuscript. JS contributed to the microbiology aspect and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved. As this is a case report without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from the institutional review board (or its equivalent).

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this manuscript is a descriptive case report without identifiers, institutional review board approval was not required

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic Order)

GMS- Gomori Methenamine Silver

ITS- Internal transcribed Spacer region

LBP- Liquid based preparation

PAP- Papanicolaou

All other abbreviations have been explained in the text of the paper.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Two cases of Cokeromyces recurvatus in liquid-based Papanicolaou tests and a review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1593-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mucormycosis caused by unusual mucormycetes, non-Rhizopus, -Mucor, and -Lichtheimia species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:411-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cokeromyces recurvatus as a human pathogenic fungus: Case report and critical review of the published literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:155-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in a postpartum Pap smear. A case report. Acta Cytol. 2001;45:79-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in a liquid-based Papanicolaou test from a pregnant woman: Report of a case. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:557-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Colonization of the vagina by fungi of genus Mucor. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 1979;1:4-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cokeromyces recurvatus Poitras, a distinctive Zygomycete and potential pathogen: Criteria for identification. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 1990;12:113-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cokeromyces recurvatus, a mucoraceous zygomycete rarely isolated in clinical laboratories. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:843-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cokeromyces recurvatus in a cervical papanicolaou test: A case report of a rare fungus with a brief review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:419-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pythiosis, lagenidiosis, and zygomycosis in small animals. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2003;33:695-720.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chronic cystitis due to Cokeromyces recurvatus: A case report. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:1062-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Severe diarrhea due to Cokeromyces recurvatus in a bone marrow transplant recipient. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1350-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cokeromyces recurvatus isolated from pleural and peritoneal fluid: Case report. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2601-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cokeromyces recurvatus infection in a bone marrow transplant recipient. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:301-2.

- [Google Scholar]