Translate this page into:

Cytopathologist-performed and ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology enhances diagnostic accuracy and avoids pitfalls: An overview of 20 years of personal experience with a selection of didactic cases

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Over the last few decades, fine needle aspiration cytology (FNA) has emerged as a SAFE (Simple, Accurate, Fast, Economical) diagnostic tool based on the morphologic evaluation of cells. The first and most important step in obtaining accurate results from FNA is to procure sufficient and representative material from the lesion and to appropriately transfer this material to the laboratory. Unfortunately, the most important aspect of this task occurs beyond the control of the cytopathologist, a key reason for obtaining unsatisfactory results with FNA. There is growing interest in the field of cytology in “cytopathologist-performed ultrasound (US)-guided FNA,” which has been reported to yield accurate results. The first author has been applying FNA in his own private cytopathology practice with a radiologist and under the guidance of US for more than 20 years. This study retrospectively reviews the utility of this practice. We present a selection of didactic examples under different headings that highlight the application of FNA by a cytopathologist, accompanied by US, under the guidance of a radiologist, in the form of an “outpatient FNA clinic.” The use of this technique enhances diagnostic accuracy and prevents pitfalls. The highlights of each case are also outlined as “take-home messages.”

Keywords

Cytopathologist-performed ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology

fine-needle aspiration diagnostic accuracy

fine-needle aspiration pitfalls

one-stop fine-needle aspiration clinic

ultrasound guidance

INTRODUCTION

The first and most important step in obtaining accurate results from fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology is to procure sufficient and representative material from the lesion and to appropriately transfer this material to the laboratory. Unfortunately, the most important aspect of this task occurs beyond the control of the cytopathologist, a key reason for obtaining unsatisfactory results with FNA.[123] In the world of cytology there is growing interest in “cytopathologist-performed ultrasound-guided FNA” (CP US-FNA), which has been reported to yield accurate results.[456789101112131415] The first author has been applying FNA in his own private cytopathology practice with a radiologist and under the guidance of US for more than 20 years. This study retrospectively reviews the first author's personal experience. We present a selection of didactic examples under different headings that highlight the application of FNA by a cytopathologist, accompanied by US, under the guidance of a radiologist, in the form of an “outpatient FNA clinic.” The use of this technique enhances diagnostic accuracy and prevents pitfalls. The highlights of each case are also outlined as “take-home messages” (THMs).

NOT EVERY CYST IS INNOCENT

Case 1: Cystic lymph node in the neck

Brief history (BH): a 43-year-old female presented with a palpable mass in the right neck. US revealed a 20 mm × 15 mm hypoechogenic lymph node (LN) in the right cervical jugular region. During US-FNA, 3 cc of hemorrhagic cystic fluid was obtained. It was believed that the cystic LN could be associated with papillary thyroid carcinoma. US was performed on the thyroid, which had not previously undergone US. The radiologist detected an 8 mm × 6 mm microcalcified nodule in the right lobe. FNA was also performed on this nodule.

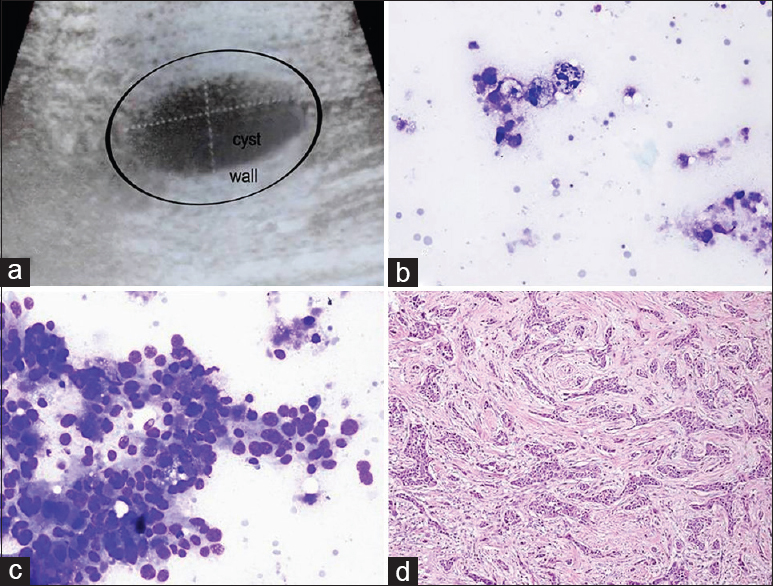

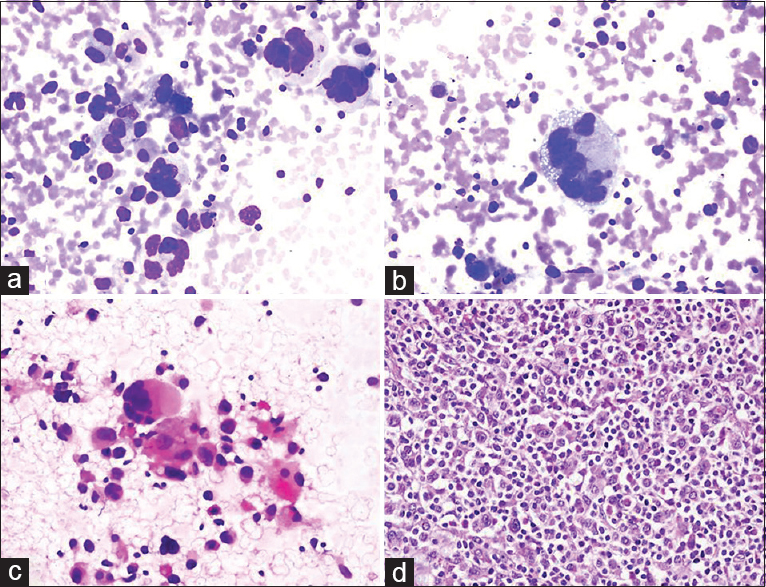

Cytologic findings: (i) LN: smears from cystic fluid showed clusters of atypical thyroid follicular cells on a cystic background with hemosiderin-laden macrophages. (ii) Thyroid nodule: the hypercellular samples revealed atypical papillary clusters with occasional intranuclear vacuoles and grooves [Figure 1]. Cytologic diagnosis: LN: Metastasis of cystic papillary thyroid carcinoma. Right thyroid nodule: Thyroid papillary carcinoma. The cytologic diagnosis was confirmed histopathologically.

- (a) Ultrasound image of the cystic cervical lymph node. (b) Cystic fluid consisting of macrophages (Pap, ×400). (c and d). Clusters of atypical follicular cells in the cystic fluid (Pap, ×400). (e) Sonographic image of the thyroid nodule. (f) A group of papillary thyroid carcinoma cells (Pap, ×400)

THMs: After the fluid was obtained from the LN during the FNA, “metastasis of thyroid papillary carcinoma,” which comes to mind first in the differential diagnosis of lesions that form cystic degenerations at the LN, was considered.[161718] Other lesions included in the differential diagnosis were hemangioma, metastasis from malignity in the salivary gland, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.[19]

Case 2: Cystic lesion in the breast

BH: a 30-year-old female complained of a palpable mass in the right breast. A cystic lesion was identified in the previous US. At the time of the US, the FNA radiologist noticed thickening in the wall surrounding the cyst that was 26 mm × 14 mm in size. First, the cyst was aspirated, and 3 cc of partially thick cystic fluid was obtained. Consequently, a sample in the form of “bird-pecking” was taken from the cystic wall. Cytologic diagnosis: (i) Cystic fluid: cystic macrophages were observed in a partially dirty inflamed background. (ii) Wall samples: malignant ductal epithelial groups were observed [Figure 2]. Histopathology: Infiltrating ductal carcinoma.

- (a) Sonographic image of the cystic breast lesion. (b) Cyst content with macrophages (Diff Quik©, ×400). (c) Aspirate from the wall showing malignant ductal cells (Diff Quik©, ×400). (d) Surgical tissue reveals infiltrating ductal carcinoma (H and E, ×200)

THM: sampling not only from the cyst but also from the wall enabled the detection of the malignancy.[20]

INNOCENT CYSTS WITH A NEGATIVE APPEARANCE

Case 1: Cystic lesion in the neck

BH: In a 35-year-old female, a hypoechoic lesion 35 mm × 15 mm in size with a cystic appearance was detected during the US due to the presence of a palpable mass in the left neck. During the US, it was noted that the cyst had no septa inside, its wall was thin, and the lesion of the cyst was almost completely full. Cytologic findings: squamous epithelial cells were observed between sporadic inflamed cells on a dirty cystic background. It was noted that some squamous cells had dyskaryotic structures with pyknotic nuclei while reactive atypia was observed in a few cells [Figure 3]. Cytologic diagnosis: Branchial cyst.

- (a-c) Cytology smears of a branchial cyst containing dyskaryotic, atypical looking squamous cells with pyknotic nuclei (a: Pap, ×200; b and c: Pap, ×400). (d) Cervical lymph node aspirate with metastatic squamous carcinoma cells from an archival case of larynx carcinoma, displayed for comparison (Pap, ×400)

THM: the cytopathologist noted that the lesion was cystic, and 10 cc of clear yellow fluid was obtained from the aspiration, during which the lesion shrank, which suggested that it could be a thin-wall cystic lesion. Cytodifferential diagnosis: Salivary gland lesion (e.g., Warthin tumor), cystic hygroma, cystic thyroid lesions, purulent inflammation (apsis) and metastasis of cystic squamous cell carcinoma (larynx, head/neck associated). In addition, squamous cell carcinoma cases associated with branchial cysts were defined in the literature.[2122]

BEWARE OF UNDIFFERENTIATED MALIGNANT CELLS IN NECK LYMPH NODES

Four different cases with similar cytomorphology are presented below.

Case 1: Lung adenocarcinoma

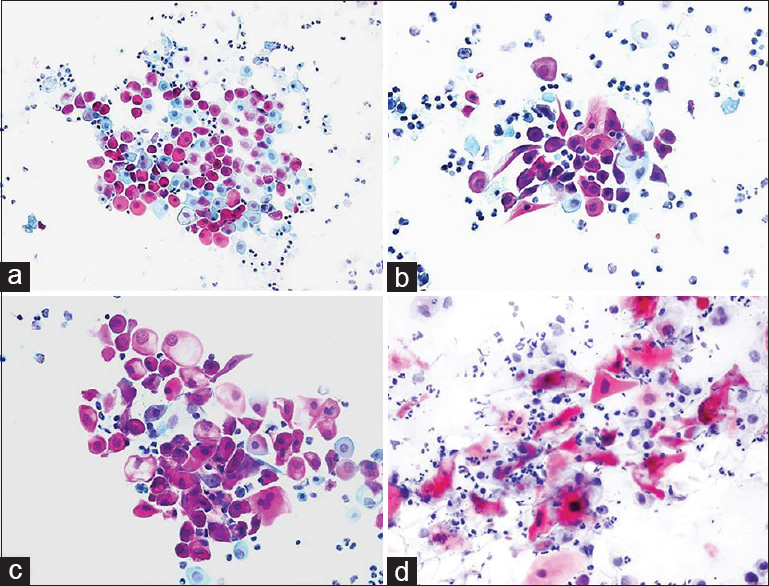

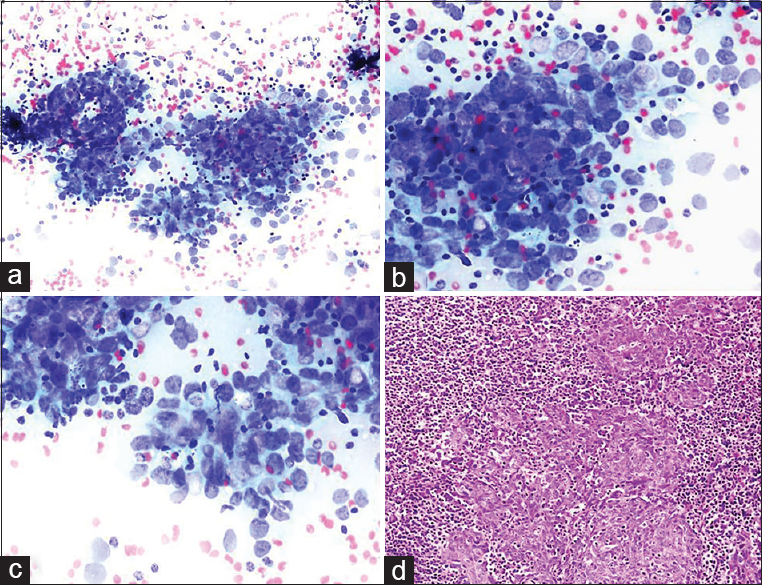

BH: A 65-year-old male presented with a 40 mm × 25 mm LN extending to the supraclavicular region in the right cervical chain in the neck. The right lung had a 3 cm area with a “ground-glass” appearance. Moreover, a cystic nodule 25 mm × 15 mm in size was present in the right thyroid. Clinical preliminary diagnosis was malignant; the primary focus was investigated (thyroid/lung?). US-FNA was applied to the LN and right thyroid nodule. The FNA of the thyroid nodule displayed findings compatible with “cystic degenerated adenomatous nodule.” LN cytologic findings: individually, scattered and sporadic groups of malignant cells were observed. The large cytoplasm cells had vacuoles and large, dark nuclei with sporadic pleomorphism [Figure 4]. Cytologic diagnosis: Adenocarcinoma. The diagnosis was interpreted as consistent with the metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma supported by the clinical/imaging picture. Follow-up: Diagnosis was confirmed by the histoimmunopathologic examination of the LN core biopsy.

- (a-d) Various smears of fine needle aspiration showing moderately pleomorphic tumor cells with large nuclei, vacuolated cytoplasm and visible nucleoli (a: Diff Quik©, ×200; b-d: Diff Quik©, ×400)

Case 2: Nodular sclerosing Hodgkin's lymphoma

BH: A 41-year-old male presented with multiple LNs in the right neck; the largest ones were 32 mm × 20 mm in the right submandibular region and 35 mm × 15 mm and 25 mm × 20 mm in the right neck. A positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan showed involvement with suspicions of malignancy in the stomach wall and the LNs. Clinical preliminary diagnosis: stomach cancer with metastasis to the neck LNs. Cytologic findings: US-FNA was used in the three LNs in the neck. Similar characteristics were observed in all LNs: Pleomorphic malignant cells represented individually in some areas and forming clusters in others were formed on a partially eosinophilic reactive lymphoid background. The nuclei of malignant cells were large, and the cytoplasm was wide and vacuolated. Enlarged nucleoli were observed in some cells [Figure 5]. Cytologic diagnosis: Undifferentiated malignant tumor cells. Comment: malignant cells with a pleomorphic nature were observed admixed with reactive lymphoid cells and eosinophilia. The cellular characteristics resembled adenocarcinoma, as suspected clinically. However, due to multiple large LNs that were identified during US, pleomorphic cells also resembled “lacunar cells” seen in “nodular sclerosing type Hodgkin's lymphoma.” Histopathology: Nodular sclerosing type Hodgkin's lymphoma.

- (a-c) Cervical lymph node aspirate showing clusters of mono- and bi-nucleated large cells containing large, pale, vacuolated cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei with demarcated prominent nucleoli (arrows) (inset to show lacunar cells with macronucleoli) (Diff Quik©, ×200). (d) Histopathologic section displaying several lacunar cells (arrows) (H and E, ×200)

THM: (1) Despite the suspicion of “gastric cancer” due to the PET-CT results, the radiologist warned about multiple LNs during the US-FNA. (2) Lacunar cells from Hodgkin's lymphoma obtained through FNA may be confused with carcinoma, melanoma, germ cell tumor, and sarcoma.[2324]

Case 3: Anaplastic large cell lymphoma

BH: A 72-year-old female presented with a mass in the neck that had been present for 1 month. A 35 mm × 20 mm LN was observed in the left submandibular region during US, while 24 mm × 16 mm and 26 mm × 15 mm nodules were observed in the right thyroid isthmus and the left lobe, respectively. Clinical prediagnosis included lymphoma and metastasis; US-FNA was performed on all three lesions. Cytologic findings: LN: high numbers of pleomorphic, multinuclear, bizarre and undifferentiated cells were noted in the left submandibular mass [Figure 6]. Thyroid nodules: The findings were compatible with “adenomatous nodule” (FNA was performed in the same session to exclude thyroid malignancy). Cytologic diagnosis of the submandibular mass was “undifferentiated pleomorphic malignant tumor.” Histoimmunopathology: Anaplastic large cell lymphoma. THM: The detection of many multinuclear, large, “bizarre” cells led us to consider the presence of three lesions during the differential diagnosis: Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, melanoma and anaplastic carcinoma/sarcoma.

- (a-c) Aspiration cytology smears reveal multinucleated, bizarrely shaped tumor cells mixed with large and small lymphocytes (a: Diff Quik©, ×200; b: Diff Quik©, ×400; c: Pap, ×200). (d) Surgical biopsy of the lymph node confirmed anaplastic large cell lymphoma

Case 4: Metastasis of undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma

BH: A 50-year-old male presented with many bilateral LNs in the neck. Clinical preliminary diagnosis was lymphoma or metastasis. An assessment of the patient's file before the FNA MRI report revealed a description of a 22 mm × 18 mm asymmetrical mass lesion in the nasopharynx. Unfortunately, this information was not indicated on the FNA requisition form. US findings: the radiologist detected many conglomerated LNs in the right and left sides of the neck during the US before the FNA. An FNA was performed from the largest LNs located at the left and right supraclavicular regions, which were18 mm × 10 mm and 30 mm × 18 mm in size, respectively. Cytologic findings: malignant tumor cells were observed individually or in scattered groups on a lymphoid background and appeared reactive. Thin fusiform particles were detected inside the nucleus in some cells in malignant clusters [Figure 7]. Cytologic diagnosis: Undifferentiated malignant tumor. Comment: the cytologic differential included the metastasis of head/neck-associated carcinoma and Hodgkin's lymphoma due to atypical mononuclear cells in the reactive lymphoid background. Histopathology: the nasopharyngeal biopsy showed undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

- (a-c) Neoplastic cells forming distinct aggregates contrasted with a reactive lymphoid background. Tumor cells presented large, pleomorphic nuclei and occasional prominent nucleoli (arrows) (a-c: Diff Quik©, a: ×200; b and c: ×400). (d) Biopsy revealed undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma (H and E, ×200)

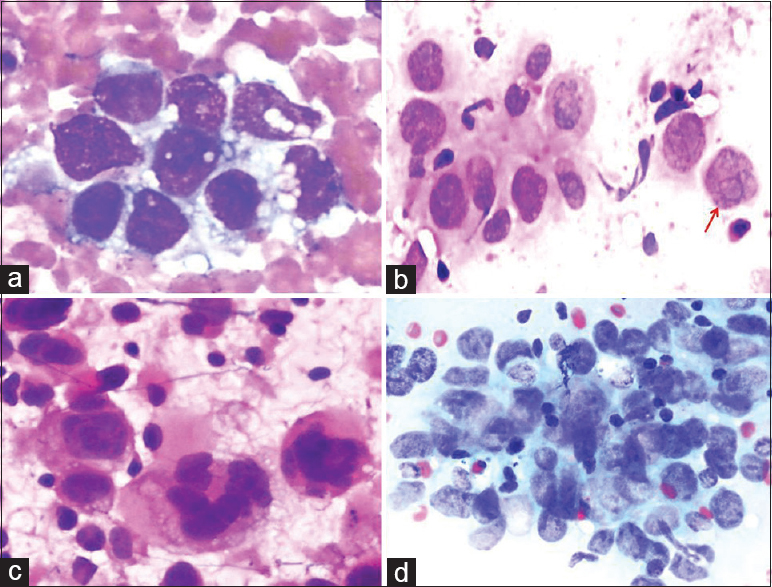

THM: (1) Metastasis in the LNs in undifferentiated carcinoma of the nasopharynx involves diagnostic challenges during the FNA.[2526] This condition may be confused with other nonkeratinized carcinoma metastases and lymphomas (especially Hodgkin's lymphoma). (2) Bizarre cells observed in undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma may resemble atypical mononuclear cells in Hodgkin's lymphoma (Hodgkin cells) and Reed–Sternberg cells [Figure 8].

- A comparative set of cytologic images showing undifferentiated pleomorphic cells in the lesions. (a) Metastatic adenocarcinoma cells (Diff Quik©, ×400). (b) Lacunar cells with demarcated prominent nucleoli (red arrow) from Hodgkin's lymphoma (Pap, ×400). (c) Bizarre cells from anaplastic large cell lymphoma (Pap, ×400). (d) Cluster of neoplastic cells from nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Pap, ×400)

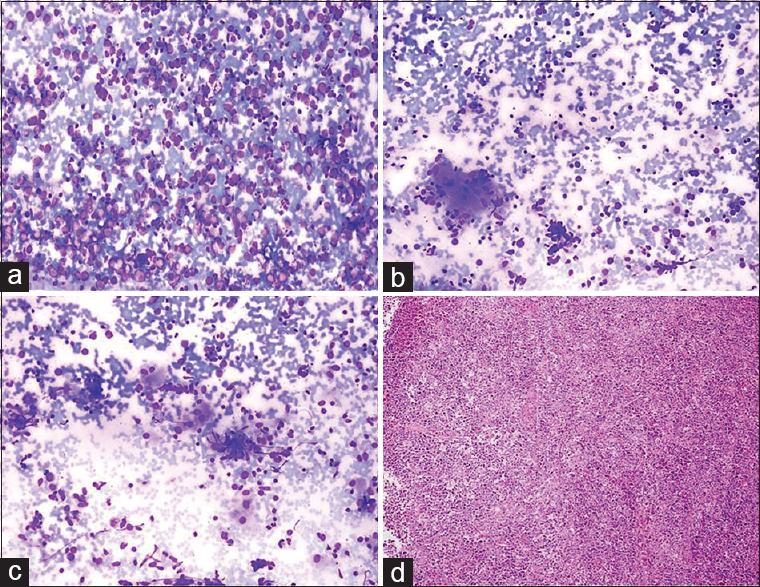

NECK LYMPH NODE: DO NOT TRUST EVERY GRANULOMA DURING THE FINE-NEEDLE ASPIRATION

Case 1: Granuloma + nasopharyngeal carcinoma

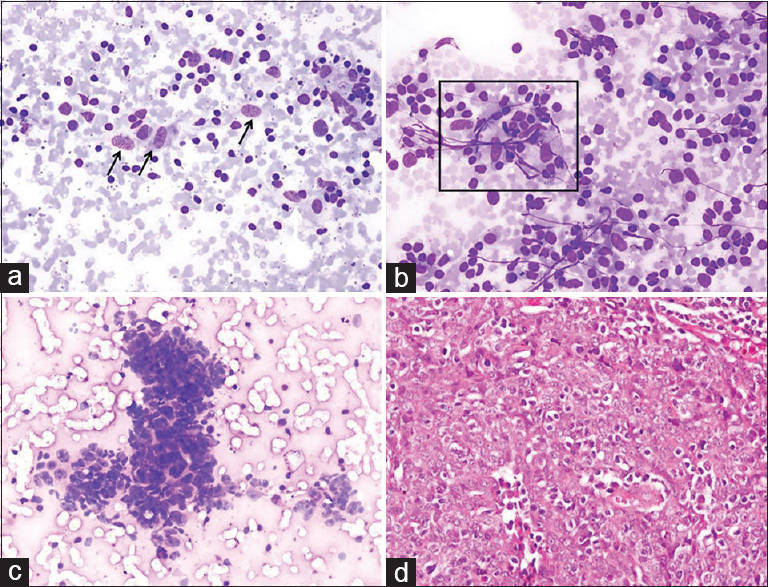

BH: US-FNA was requested for a 45-year-old male due to the presence of a palpable LN 2.5 cm below the sternocleidomastoid muscle in the right neck and 1 cm below the sternocleidomastoid muscle in the left neck. US-FNA was performed on these two lesions.

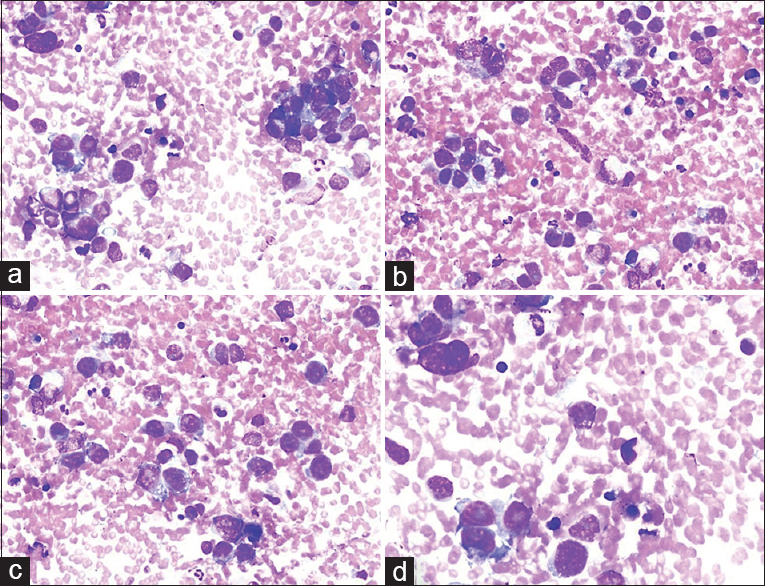

Cytologic findings: Epithelioid histiocytes and epithelioid histiocytic clusters forming granuloma-like structures were observed on a reactive lymphoid background. Undifferentiated malignant cells, which formed scattered groups around granulomatous structures, were also noted. Cytologic diagnosis: an undifferentiated malignant tumor that could be a metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma/Hodgkin's lymphoma [Figure 9]. Histopathology: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (nonkeratinized squamous cell type).

- (a) Scattered epithelioid histiocytes (arrows) mixed with reactive lymphoid cells (Diff Quik©, ×200). (b) A group of epithelioid histiocytes forming a granuloma-like aggregate (square) (Diff Quik©, ×200). (c) A cluster of cohesive neoplastic cells admixed with lymphocytes. Tumor cells showed moderate nuclear pleomorphism and scanty cytoplasm (Diff Quik©, ×200). (d) Histologic image of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (H and E, ×200)

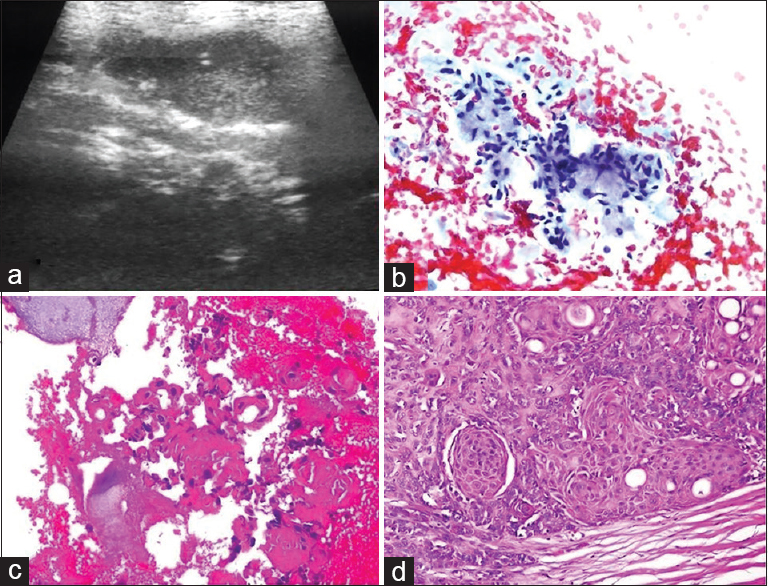

Case 2: Granuloma + Hodgkin's lymphoma

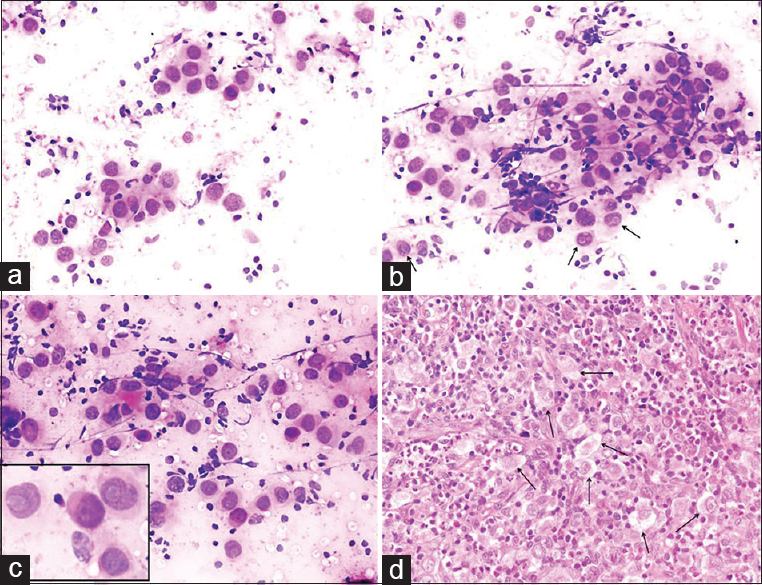

BH: A 20-year-old male had a mobile soft mass with a diameter of 30 mm that had been present for 6–7 months in the right supraclavicular region. Numerous LNs with diameters of 25, 25, and 15 mm were also detected in the right cervical region during the US. A US-FNA was performed. Cytologic findings: a heteromorphic structure composed of small-large lymphocytes and few eosinophils was observed. Sporadic and scattered epithelioid histiocytes and epithelioid histiocytic groups forming granuloma-like structures were noted on a reactive lymphoid background. “Atypical mononuclear cells with an undefined nature” were observed in the regions adjacent to these groups. Necrosis and typical granulomas were not observed [Figure 10]. Cytologic diagnosis and remarks lymphoid proliferation comprising a granulomatous reaction, which may be a component of granulomatous lymphadenitis (e.g., tuberculosis/sarcoid) or the reflection of an underlying neoplasia/lymphoproliferative lesion (Hodgkin's lymphoma) not represented by FNA. Histopathology: Mixed type Hodgkin's lymphoma.

- (a) Epithelioid histiocytes (black arrows) and a few cells with relatively larger and naked nuclei with prominent nucleoli (red arrows) admixed with reactive lymphoid cells (Diff Quik©, ×200). (b and c) A group of epithelioid cells forming a granuloma-like pattern (squares) (Diff Quik©, ×200). (d) A focus of granuloma in the histologic section of the lymph node biopsy diagnosed as Hodgkin's lymphoma (H and E, ×200)

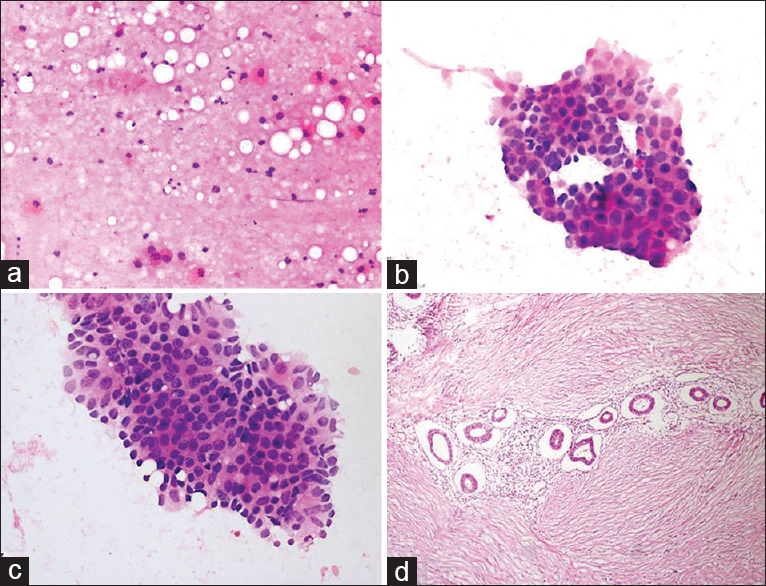

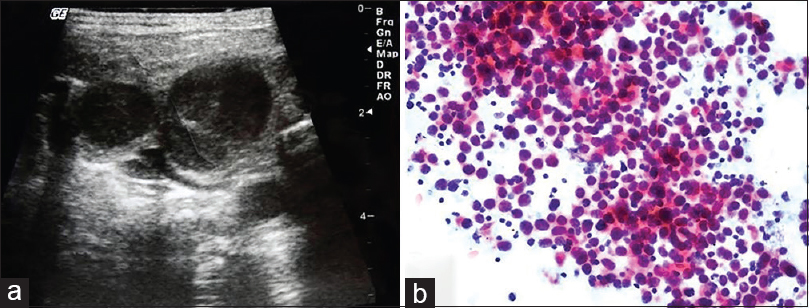

Case 3: Granuloma + Burkitt lymphoma

BH: A 6-year-old male had an LN 30 mm in diameter in the right submandibular region and multiple LNs, the largest of which measured 25 mm and 15 mm, in the right cervicojugular region. US findings: Compatible with abscess/necrotic appearance. A US-FNA was performed on the largest LN (3 cm in size) in the right submandibular region. The procedure could not be repeated on the other LNs, as the pediatric patient could not be controlled.

Cytologic findings: Epithelioid histiocytes, epithelioid histiocytic granulomas, and Langhans-type giant cells were observed adjacent to a cell population with a high number of large atypical lymphoid cells [Figure 11]. Cytologic diagnosis: atypical lymphoid proliferation comprising granulomatous structures. Comment: granulomatous structures may be components of granulomatous inflammation (e.g., tuberculosis, sarcoid) or may develop secondarily to a lymphoproliferative lesion or carcinoma metastasis. Histopathology: Burkitt lymphoma with secondary granulomatous inflammatory foci (no information could be obtained regarding the cause of granulomatous inflammation proposed in histopathological diagnosis).

- (a) Smear from the lymph node aspiration showing a monomorphic, homogenous infiltration with large atypical lymphoid cells (Diff Quik©, ×200). (b and c) Occasional epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells seen within the lymphoid infiltrate (Diff Quik©, ×200). (d) Biopsy of the lymph node reveals diffuse large cell lymphoma diagnosed as Burkitt lymphoma backed by immunostaining (H and E, ×200)

THM: (1) In the absence of typical cytological components of granulomatous inflammation, individually or sporadically represented epithelioid histiocytes and granuloma-like structures are not sufficient for the diagnosis of “granulomatous inflammation.” (2) In such cases, it would be more appropriate to write “granulomatous reaction” and add a remark in a similar context like our above-mentioned comment. (3) Granulomatous reactions and granulomas are not usually expected to accompany non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; they mostly accompany Hodgkin's lymphoma.[25262728]

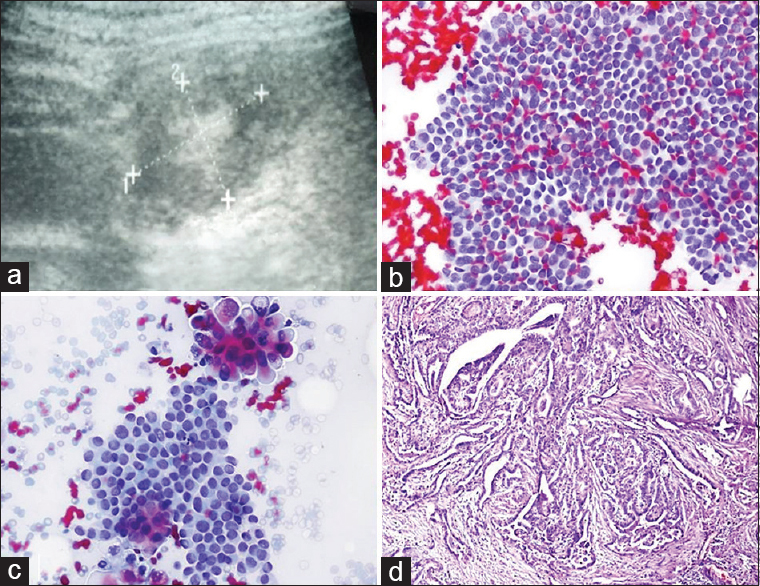

BENEFITS OF SAMPLING FROM DIFFERENT SITES OF THE MASS

Sample case

BH: a 29-year-old male presented with a mass in the left parotid. A hypoechogenic mass, 37 mm × 25 mm in size with irregular borders, was observed during the US. Samples were taken through radial needle movements to represent different regions of the mass. A cell block was prepared from the residual fluid.

Cytologic findings: Multiple slides were prepared. Parotid ductal epithelial/myoepithelial cells were present and were mixed with chondromyxoid material on five slides. Although this condition led to the consideration of “pleomorphic adenoma,” atypical squamous cells and cell ghosts were noted on a degenerated and necrotic background in one preparation. Atypical cells were more prominent in the cell block and exhibited characteristics typical of malignancies [Figure 12]. Cytologic diagnosis: Atypical salivary gland lesion. Comment: although the FNA samples led to the consideration of pleomorphic adenoma, one preparation and cell block contained atypical squamous cells with a suspicion of malignancy. Therefore, the possibility of “carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma” could not be excluded. Histopathology: Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma.

- (a) Sonogram shows a large hypoechoic mass with irregular borders in the parotid gland. (b) Aspiration smear shows a population of uniform cells embedded in the chondromyxoid material (Pap, ×400). (c) Cell block from the aspirate reveals a focus of atypical squamous cells (H and E, ×200). (d) Histologic section of the area with squamous cell carcinoma (H and E, ×200)

THM: lesions that consist of different components in terms of histopathology may lead to diagnostic error with FNA. Therefore, a sufficient number of cells and representative cell samples should be obtained during FNA to achieve diagnostic accuracy. Similar situations may also present in cases with multiple thyroid nodules. Malignancy may emerge from the nondominant nodules.[29]

ECTOPIC LESIONS MAY BE A PITFALL IN FINE-NEEDLE ASPIRATION

Sample case

BH: a 37-year-old female presented with a mobile solid mass with subcutaneous pain in the lower quadrant of the abdomen. A 27 cm × 25 cm hypoechogenic lesion was detected during US. It was noted during US-FNA that the patient had a caesarian scar in the abdomen and that the nodule was close to the scar; 0.5 cc of hemorrhagic fluid was obtained. Cytologic findings: glandular cellular islets of various dimensions were observed on a background consisting of hemosiderin macrophages. Moderate atypia was detected in the cells [Figure 13]. Cytologic diagnosis: endometriosis externa was confirmed histopathologically.

- (a) Smear showing cystic background with occasional histiocytes (H and E, ×200). (b and c) Cytology reveals an aggregate of glandular epithelial cells with nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia and anisonucleosis (Diff Quik©, ×200 and × 400). (d) Histology showed proliferative endometrial glands in the lymphocytic fibrous stroma (H and E, ×200)

THM: This case is an example that demonstrates the benefit of having the CP his own FNA. Noting the proximity of the mass to the caesarian scar and obtaining a hemorrhagic cystic aspirate provided preliminary insight. Ectopic lesions may lead to surprises after FNA. Such cases may give rise to false results, especially when they are in unexpected locations.[303132]

IS FINE-NEEDLE ASPIRATION CYTOLOGY ALWAYS TO BE BLAMED?

In case of incompatibility in the FNA-histopathological diagnosis, the clinician mostly relies on the histopathological diagnosis and not on the FNA. The evaluation of FNA and histopathological preparations together is generally not considered. Therefore, is a histopathological diagnosis always superior to an FNA diagnosis?

Case 1: The patient spoiled the game!

BH: a 42-year-old female was referred to us for FNA due to her thyroid nodule. The US showed a multinodular goiter. A microcalcified nodule 16 mm × 11 mm in size in the right thyroid lobe was considered important; a US-FNA was performed. Cytologic findings and diagnosis: Smears presented typical findings of thyroid papillary carcinoma [Figure 14]. Surgery and afterward: After a certain period, the patient angrily came to my office with the pathology report in her hand, trying to reproach me by saying; “It turned out to be benign after surgery. You told me it was cancer; you made me go through this stress.” I gave the preparations to the patient and directed her to the pathology institution that had reported that her nodule was benign.

- (a) Ultrasound image of the thyroid nodule with central calcification. (b and c) Fine-needle cytology findings are consistent with papillary carcinoma (Pap, ×200 and × 400). (d) Histopathologic examination of the nodule confirmed the diagnosis of papillary carcinoma (Pap, ×200)

The FNA slides received the diagnosis of “papillary carcinoma” during the consultation at the institution. Consequently, the thyroidectomy specimen was sampled again. It was determined that a nodule that was overlooked and not sampled the first time turned out to be “papillary carcinoma.”

The thyroidectomy material was sent to pathology from the operation theater with the note reading “multinodular goiter + total thyroidectomy.” The information of malignancy at FNA was not specified.

THM: (1) If the patient had accepted the pathology report and not taken into account the FNA result, she could have experienced eventual metastasis because she would not have received radioactive iodine therapy and would not have been monitored. (2) Following the first pathology report, the surgeon did not take into account the incompatibility between the cytological and histological diagnoses. When the patient investigated herself, her condition turned out to be “real.”

Case 2: This time the game was spoiled by the cytopathologist!

BH: an FNA was requested for a 45-year-old female patient with multiple sclerosis due to the presence of an LN in the neck. Multiple LNs, the largest of which was 3 cm, were detected during the US. A US-FNA was performed on the dominant LN located in the left cervical region. Cytologic findings: homogenously spread monomorphic, large, round, atypical lymphoid cells were detected [Figure 15]. Cytologic diagnosis: Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Surgical biopsy and afterward: The biopsy from the neck was reported to be a “sebaceous cyst.” I wrote a letter to her physician and emphasized that there were bilateral multiple LNs in the neck and that the FNA picture did not reflect a “sebaceous cyst” at all. I called the patient 5 months later. After receiving my note, her physician excised the LN on which I had performed the FNA. The patient was diagnosed with “diffuse large B-cell lymphoma” and received treatment. It turned out that the mass described as a “sebaceous cyst” was removed by the physician, as it was easy to remove from the surface of the opposite side of the LNs that underwent FNA!

- (a) Sonogram of the cervical chain shows hypoechoic enlarged lymph nodes. (b) Aspiration from the dominant neck lymph node presented homogenous monomorphic lymphoid infiltration composed of atypical large cells (Pap, ×200)

CONCLUSION

As reported by Kocjan, the “FNA technique is simple but not banal. It requires a certain manual dexterity in the same way as surgical procedures do. These need to be acquired before proceeding to take diagnostic samples.” The most important question of the cytopathologist who assesses FNA preparations is, “Do the cells that I see match with the clinical and sonographic findings of the patient; do these cells represent the lesion?”[2] Performing an FNA in an accurate manner from an adequate region of the lesion and preparing it appropriately is as important as interpreting the FNA correctly, just like in the example of “the chef who doesn't let others purchase the ingredients of a special dish he will cook and selects them himself from the supermarket.”

We have presented a selection of didactic examples under different headings, showing that the application of FNA by a cytopathologist, accompanied by US, under the guidance of a radiologist, in a setting of an “outpatient FNA clinic” enhanced diagnostic accuracy and prevented pitfalls.

The organization of this model as a private practice by the cytopathologist is more easily compared with the hospital setting.[481029] There is growing interest, especially in the United States, in establishing CP US-FNA in an academic setting; the number of publications on this topic has increased.[6789101112131433] Most of these publications indicate that the cytopathologist may use the US device himself. However, the utilization of a US device by the cytopathologist may not be possible in each country due to medical license and medicolegal reasons.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that there are no relevant competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

NP: Conceived and designed the study, collected data, drafted and edited the manuscript. BO: Participated in figures and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the paper.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors confirm that there are no ethical concerns. As this is a retrospective review study without identifiers, approval from the Institutional Review Board was not required.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

BH - Brief history

CP US-FNA - Cytopathologist-performed ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration

FNA - Fine-needle aspiration

H and E - Hematoxylin and eosin stain

LN - Lymph node

Pap - Papanicolaou stain

THM - Take-home message

US - Ultrasound

US-FNA - Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank to Dr. Kadri Yazal, Radiologist, Konrad Private Radiology Center, Izmit, Kocaeli, Turkey for his invaluable sonographic contribution. This study was presented in part as a lecture at the 26th National Pathology Congress and 7th National Cytopathology Congress held in Antalya, Turkey on November 2-6, 2016.

REFERENCES

- Diagnostic accuracy of fine-needle aspiration biopsy is determined by physician training in sampling technique. Cancer. 2001;93:263-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology: Inadequate rates compromise success. Cytopathology. 2003;14:307-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inadequate rates are lower when FNAC samples are taken by cytopathologists. Cytopathology. 2003;14:327-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Initiating private pathology practice ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration: Beginners's road map and survival guided. Pathol Case Rev. 2013;18:53-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The case for pathologist ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Cancer. 2008;114:463-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytopathologist-performed ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration and core-needle biopsy: A prospective study of 500 consecutive cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:317-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Value of cytopathologist-performed ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration as a screening test for ultrasound-guided core-needle biopsy in nonpalpable breast masses. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:262-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study of 200 head and neck FNAs performed by a cytopathologist with versus without ultrasound guidance: Evidence for improved diagnostic value with ultrasound guidance. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:743-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Establishing ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in academic setting. Pathol Case Rev. 2013;18:48-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathologist ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration: Take the plunge and reap the benefits! Pathol Case Rev. 2015;20:230-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Value of ultrasound guidance in cytopathologist-performed aspirations of palpable lesions. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2015;4:195-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytopathologist-performed ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of head and neck lesions: The Weill Cornell experience. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2015;4:313-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Young investigator challenge: Building an ultrasound-guided FNA clinic-our 5-year experience: From project to practice. Cancer. 2017;125:161-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound guided FNA of thyroid performed by cytopathologists enhances Bethesda diagnostic value. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:787-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytopathologists can reliably perform ultrasound-guided thyroid fine needle aspiration: A 1-year audit on 3715 consecutive cases. Cytopathology. 2016;27:115-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic features of metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma in cervical lymph nodes. Acta Cytol. 2002;46:1043-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Importance of foamy macrophages only in fine needle aspirates to cytologic diagnostic accuracy of cystic metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma. Acta Cytol. 2010;54:249-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cystic lymph nodes in the lateral neck as indicators of metastatic papillary thyroid cancer. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:240-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Differential diagnosis of cystic neck lesions. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120:409-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improved fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology results with a near patient diagnosis service for breast lesions. Cytopathology. 2000;11:32-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metastatic squamous carcinoma presenting as a neck cyst. Differential diagnosis from inflamed branchial cleft cyst in fine needle aspirates. Acta Cytol. 1993;37:494-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant first branchial cleft cysts presented as submandibular abscesses in fine-needle aspiration: Report of three cases and review of literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:876-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Syncytial variant of nodular sclerosing Hodgkin's disease: A diagnostic pitfall in fine-needle aspiration cytology. J Cytol. 2014;31:91-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma grade 2: A diagnostic challenge to the cytopathologists. Cancer. 2017;125:104-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic features of metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:340-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration cytology of metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma in cervical lymph nodes: Comparison with metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma, and Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;28:18-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aspiration cytology of malignant neoplasms associated with granulomas and granuloma-like features: Diagnostic dilemmas. Cancer. 1998;84:84-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical lymph node metastasis of extramedullary plasmacytoma of the tonsil presenting with granulomatous lymphadenitis in fine needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 2010;54:733-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignancy rate in nondominant nodules in patients with multinodular goiter: Experience with 1,606 cases evaluated by ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology. Cytojournal. 2011;8:19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ectopic lesions as potential pitfalls in fine needle aspiration cytology: A report of 3 cases derived from the thyroid, endometrium and breast. Acta Cytol. 2007;51:222-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration cytology of endometriosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45:359-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration biopsy: The new challenges and opportunities for cytopathologists. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:1017-8.

- [Google Scholar]