Translate this page into:

Cytomorphology of Erdheim–Chester disease presenting as a retroperitoneal soft tissue lesion

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Erdheim–Chester disease (ECD) is a rare, multisystem disorder of macrophages. Patients manifest with histiocytic infiltrates that lead to xanthogranulomatous lesions in multiple organ systems. The cytologic features of this disorder are not well characterized. As a result, the cytologic diagnosis of ECD can be very challenging. The aim of this report is to describe the cytomorphology of ECD in a patient presenting with a retroperitoneal soft tissue lesion. A 54-year-old woman with proptosis and diabetes insipidus was found on imaging studies to have multiple intracranial lesions, sclerosis of both femurs and a retroperitoneal soft tissue mass. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) and a concomitant core biopsy of this abnormal retroperitoneal soft tissue revealed foamy, epithelioid and multinucleated histiocytes associated with fibrosis. The histiocytes were immunoreactive for CD68, CD163, Factor XIIIa and fascin, and negative for S100, confirming the diagnosis of ECD. ECD requires a morphologic diagnosis that fits with the appropriate clinical context. This case describes the cytomorphologic features of ECD and highlights the role of cytology in helping reach a diagnosis of this rare disorder.

Keywords

Cytology

Erdheim–Chester disease

fine needle aspiration

histiocytosis

langerhans cell histiocytosis

retropeitoneum

xanthomatous

INTRODUCTION

The histiocytic syndromes are a rare, heterogeneous group of neoplastic and non-neoplastic disorders that are challenging to diagnose.[12] They arise from a common CD34 positive progenitor cell within the bone marrow and demonstrate a pathologic accumulation of histiocytes.[1–3] They include dendritic cell related disorders such as Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) and macrophage related disorders, also known as the non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses (non-LCH), which include the hemophagocytic syndromes, sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (SHML or Rosai-Dorfman disease) and Erdheim–Chester disease (ECD). Clinically, the non-LCH are benign proliferative disorders that can be divided into three major groups: those with i) primarily cutaneous involvement; ii) cutaneous and systemic involvement; and iii) primarily extracutaneous involvement, such as ECD.[4]

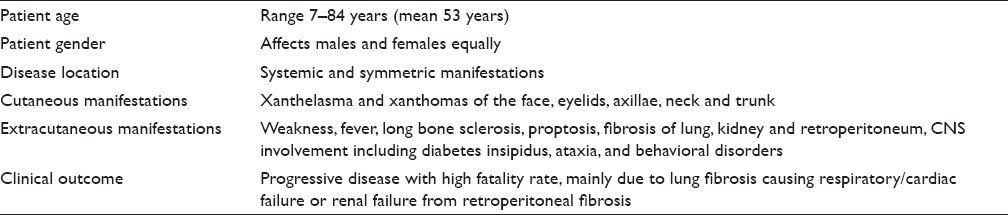

ECD, also known as polyostotic sclerosing histiocytosis, is a non-LCH disorder that may be confused with LCH.[4–7] Histiocytic infiltration in patients afflicted with ECD leads to xanthogranulomatous lesions that may involve multiple organ systems. Clinically, ECD demonstrates symmetrical osteosclerosis of the diaphyseal and metaphyseal regions of long bones. More than 50% of cases also demonstrate extraskeletal organ involvement, most commonly affecting the kidney, retroperitoneum, skin, brain, cardiovascular system and lung [Table 1].[4–9] Less commonly, the retro-orbital tissue and pituitary gland may be involved causing exophthalmos and diabetes insipidus, respectively. Retroperitoneal fibrosis may cause ureteral obstruction and eventual renal failure. Patients may develop other central nervous system manifestations such as ataxia and paraplegia.[410] The prognosis of ECD appears to be much worse than the other histiocytoses,[711] which is why it is important to correctly diagnose this disease.

There are two types of histiocytes: dendritic cells and those derived from the macrophage/monocyte cell line. The dendritic cells include Langerhans cells of the skin and bronchial epithelium, as well as interdigitating and dendritic reticulum cells in lymph nodes and the spleen. They are involved in antigen presentation to lymphocytes and a subset is immunoreactive for S100 and CD1a. The monocyte/macrophage cell line consists of phagocytic cells that include tissue macrophages, osteoclasts, microglia, Kupffer cells and circulating monocytes. A subset of these cells is immunoreactive for CD68 and Factor XIIIa. The diagnosis of ECD is confirmed by tissue biopsy in the appropriate clinical setting showing histiocytes with non-Langerhans cell features. Histiocytes in ECD are immunoreactive for macrophage (CD68, CD14, CD163) and xanthogranuloma (Factor XIIIa, fascin) markers, but not for LCH (S100, CD1a) markers.[12] Also, ECD histiocytes do not contain Birbeck granules ultrastructurally.

Unlike LCH in which the cytologic features are well described in the literature,[13–17] the authors are aware of only one case describing the cytologic features of ECD in the literature.[18] Therefore, the aim of this report is to share the unique cytomorphologic findings in another case of ECD and to highlight the key cytologic features that were helpful in reaching this challenging diagnosis.

CASE REPORT

Clinical features

A 54-year-old woman with a past medical history of type II diabetes mellitus and alleged Paget's disease of the bone presented with progressive proptosis, exophthalmus, central diabetes insipidus and shortness of breath related to cardiac tamponade. Magnetic resonance image (MRI) of her brain revealed retro-orbital and intracranial lesions involving the posterior falx and tentorium. A trans-sphenoidal biopsy was non-diagnostic due to scant cellularity. Lower limb X-rays identified areas of sclerosis in her femoral bones. The patient developed cardiopulmonary arrest and bilateral blindness. A subsequent contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a large pericardial effusion and thickening of the visceral pericardium as well as an infiltrating process in the retroperitoneum, predominately involving the perinephric spaces, left paraaortic, and interaortacaval spaces. There was also infiltration of the adrenal glands and peri-adrenal fat and extensive perivascular infiltration with encasement of the celiac artery, superior mesenteric artery, renal arteries and veins [Figure 1]. She underwent an ultrasound-guided 25-gauge fine needle aspiration (FNA) and concomitant 18-gauge core needle biopsy of the perirenal lesion. The patient was treated with corticosteroids and received whole-brain radiation. She was discharged to a rehabilitation facility and lost to follow-up after 1 year.

- CT scan of the abdomen showing a thickened soft tissue rind of perinephric tissue (yellow arrow), infiltration of the retroperitoneum in the paraaortic and interaortocaval spaces (blue arrow), as well as encasement of the superior mesenteric artery (pink arrow)

Cytological findings

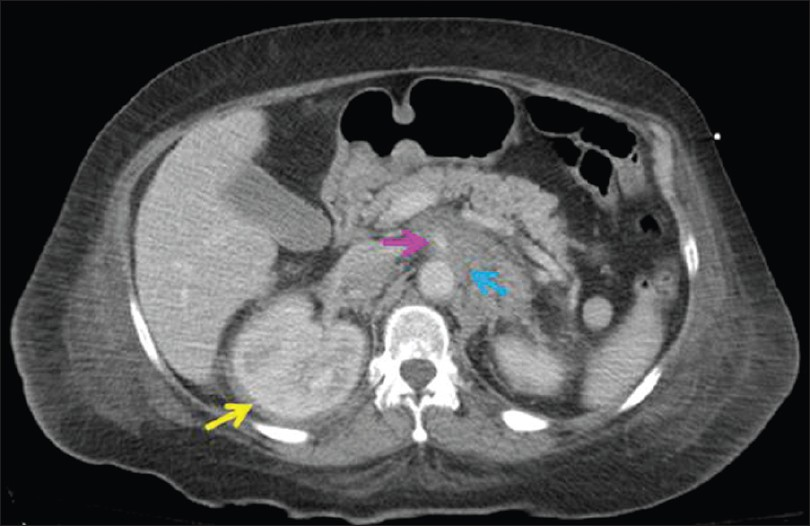

Direct smears stained with Diff-Quik (air dried) and Papanicolaou stains (alcohol fixed) and ThinPrep (Cytolyt fixed) slides were prepared from aspirated material, along with touch preparations of the core biopsies. Material collected for cell block was fixed in formalin and sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HandE). The cytology samples were of low cellularity and demonstrated bland epithelioid histiocytes arranged in clusters as well as individual foamy macrophages and occasional binucleated and multinucleated histiocytes [Figure 2]. The nuclei of these histiocytes did not have grooves or pseudoinclusions. Mitoses were not observed. The FNA also contained scant fibrous tissue fragments that contained focal admixed small lymphocytes. Eosinophils were absent. There was insufficient cell block material to perform ancillary studies.

- Various histiocytes from touch preparations are shown including a) a bland xanthomatous histiocyte, b) binucleated and c) multinucleated histiocyte (600× magnification, Diff-Quik stain). d) A cluster of monomorphic epithelioid histiocytes are shown in the FNA sample (ThinPrep, 600× magnification, Papanicolaou stain).

- Note that their nuclei are not grooved and are without pseudoinclusions

Histopathologic findings

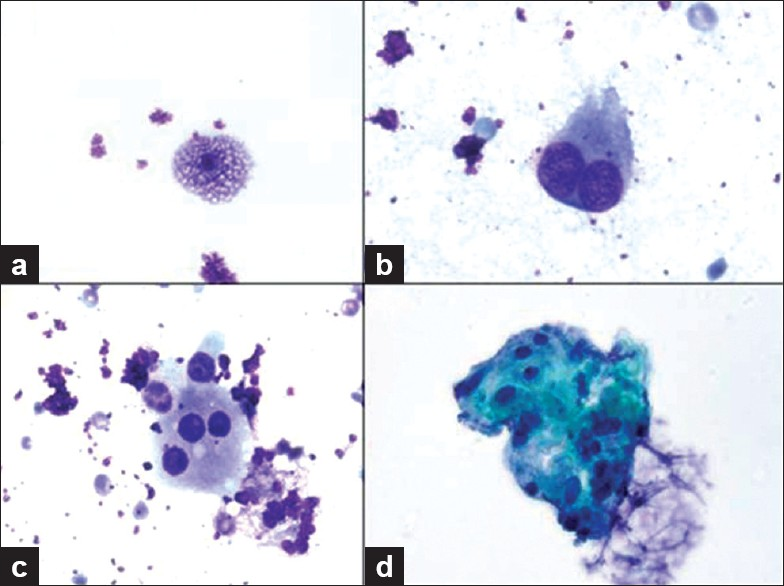

The core biopsy showed predominantly dense fibrotic tissue associated with bland spindled cells and epithelioid histiocytes that were focally aggregated in loose clusters [Figure 3]. No features of malignancy (atypia, necrosis, mitoses) were seen. A Masson trichrome stain highlighted the presence of dense collagen fibrosis.

- Core biopsy from perinephric rind showing dense fibrotic tissue associated with spindle cells and epithelioid foamy histiocytes that are focally clustered (left region of the image). A few scattered small lymphocytes are also present, but no eosinophils or acute inflammatory cells are seen. (200× magnification, H and E stain)

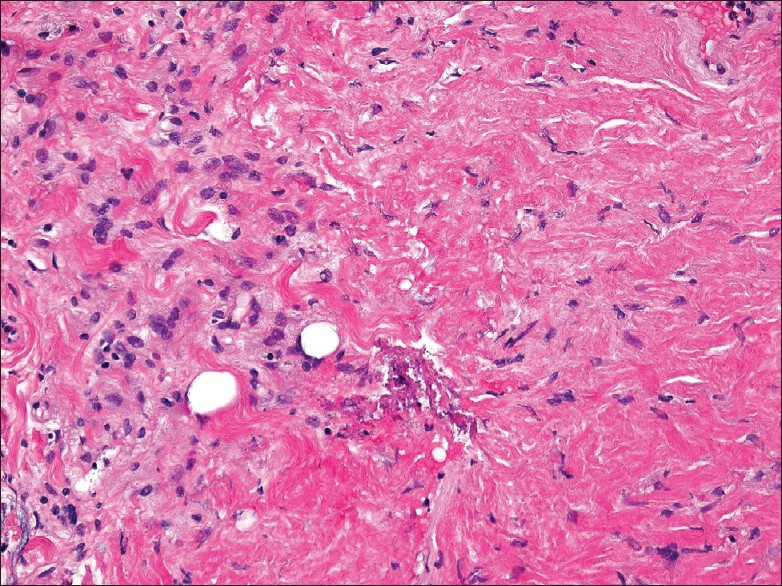

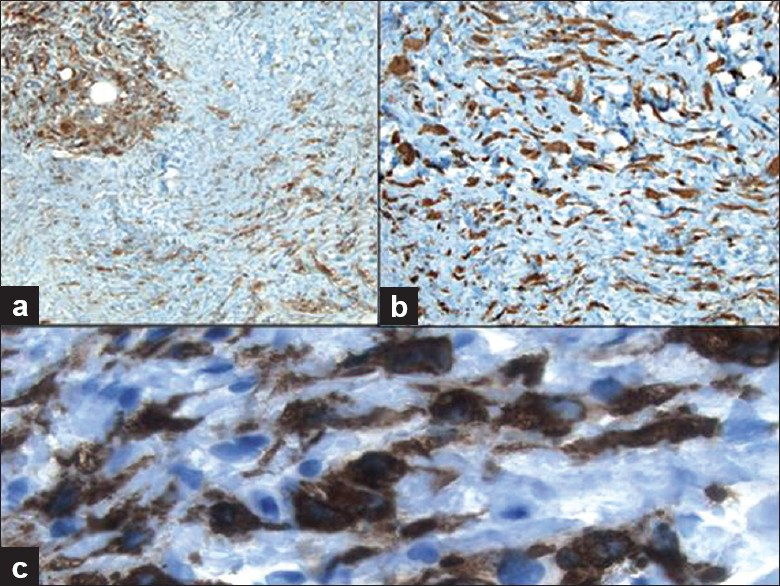

Immunohistochemical findings

Immunohistochemical stains performed on the core biopsy [Figure 4] showed that the spindled cells were positive for CD34 and that both spindled and epithelioid cells were positive for CD163, Factor XIIIa and fascin, but were negative for pankeratin, S100, beta-catenin, CD117, desmin, actin and calponin. CD68 stained the focal clusters of epithelioid histiocytes. CD45 (LCA) and bcl-2 highlighted the scattered lymphocytes. Ki67 staining was not increased in lesional cells.

- Immunohistochemical work-up of the core biopsy demonstrates that the histiocytes are immunoreactive for a) CD68 (100× magnification), b) Factor XIIIa (200× magnification) and c) CD163 (400× magnification)

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of ECD in our patient, initially established on clinical and radiological grounds, was confirmed by appropriate morphologic evaluation. ECD is a rare, non-inherited disease of uncertain pathogenesis first described in 1930 by Chester as a distinct form of “lipogranulomatosis with bony alterations.”[19] It is now known to be a primary disorder of monocytes–macrophages that exhibit distinct cytokine activation.[2021] Some cases may even represent clonal histiocytic proliferations.[2223] While most patients with ECD present with osteosclerotic lesions of the long bones,[24] extraskeletal involvement occurs in many reported cases.[725] Our patient manifested with bilateral exophthalmos, central nervous system and cardiac disease, as well as retroperitoneal fibrosis with histiocytic infiltration. ECD may present initially with retroperitoneal fibrosis,[26] and in this anatomic location could mimic other non-neoplastic (e.g. fibromatosis) and neoplastic (e.g. sarcoma) entities. In the retroperitoneum, the mass-like or perirenal rind-like histiocytic proliferation of ECD may be also be misdiagnosed as xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis.[2728] Treatment of patients with ECD is reserved for those individuals who are symptomatic, have organ dysfunction or central nervous system involvement. While there is no cure, current treatment options include interferon alpha, systemic chemotherapy, corticosteroids and/or radiation therapy.

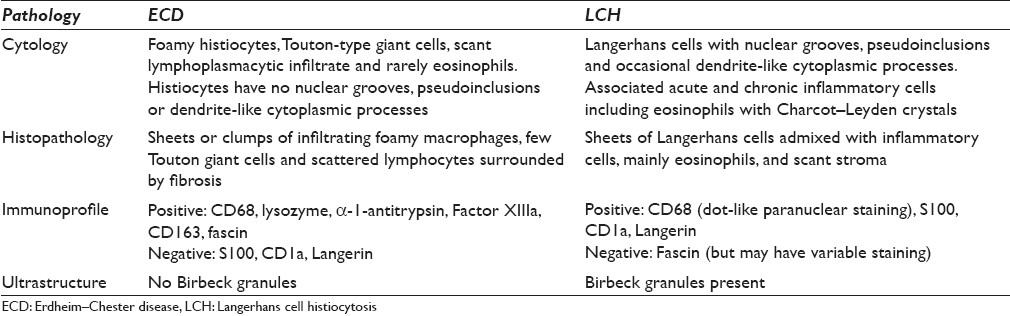

The diagnosis of ECD typically requires a biopsy of involved tissues, since this disease must be distinguished from the more common LCH, with which it shares similar clinical features. The histopathology of ECD is well characterized and usually shows infiltrates of monomorphic foamy (xanthomatous) macrophages, scattered multinucleate (Touton) giant cells and interspersed chronic inflammatory cells (predominantly lymphocytes) surrounded by fibrosis. While eosinophils may rarely be seen in ECD, they tend to be fewer in number than the eosinophilia observed in specimens procured from patients with LCH. ECD must be distinguished from other histiocytic conditions (e.g. LCH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis), dendritic cell disorders, granular cell tumor, metastatic solid and hematopoietic neoplasms (e.g. renal cell carcinoma, oncocytic neoplasms) and reactive conditions (e.g. granulomas, malakoplakia). It is important not to dismiss such a case of ECD as merely benign fibrous tissue with associated hisitocytes. Thus, clinical and radiological correlation along with appropriate immunostaining in clinically suspicious cases can be very helpful given the bland, benign-appearing nature of these lesions. A comparison of the pathology between ECD and LCH is shown in Table 2. The foamy macrophages of ECD demonstrate non-Langerhans features including lack of nuclear grooves, absence of Birbeck granules and immunoreactivity for CD68 (PGM1), lysozyme, α-1-antitrypsin, CD163, Factor XIIIa, CD14 and fascin, with concomitant negative staining for CD1a and Langerin. There are some reported cases of ECD in which histiocytes demonstrated S100 positivity.[1129] Cytologic atypia (e.g. prominent nucleoli and spindle cell sarcoma-like areas), as may be identified in histiocytic sarcoma and dendritic cell sarcoma, is not a feature of ECD. No consistent cytogenetic or molecular genetic abnormalities have been identified with ECD.

The cytopathology of ECD is not yet characterized. To the best of our knowledge, we are aware of only one other case report describing the cytologic features of ECD in the literature.[18] In this other case report, the diagnosis of ECD was made on an intraoperative squash preparation from a brain lesion of a 26-year-old young man. The squash preparations showed a mixed cellular proliferation of lymphohistiocytic elements along with large, multinucleated cells with vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm. In our case, the specimen was of low cellularity due to the associated fibrosis; however, there were foamy histiocytes including binucleate and multinucleated cells. Obtaining a concomitant core biopsy in such cases is therefore recommended. Unlike LCH, these macrophages neither exhibited nuclear grooves, pseudoinclusions or dendrite-like cytoplasmic processes, nor were associated with eosinophils. The cytologic findings of deep-seated juvenile xanthogranulomas may show similar features.[3031]

Albeit that ECD is a rare condition, patients presenting with the clinical features of this histiocytosis will likely require a pathologic evaluation during their work-up in order to determine the correct diagnosis. This case not only highlights the cytologic features of ECD that may be encountered, but also alerts cytologists to consider this non-Langerhans histiocytic disorder in cases showing xanthogranulomatous infiltration.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that they qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE. All authors are responsible for the conception of this study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is a case report without patient identifiers, approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) is not required at our institution.

EDITORIAL / PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and reviewers are blinded for authors)through automatic online system.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2011/8/1/22/91242.

REFERENCES

- Contemporary classification of histiocytic disorders. The WHO Committee On Histiocytic/Reticulum Cell Proliferations. Reclassification Working Group of the Histiocyte Society. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:157-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Other histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms. In: Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Vardiman JW, Campo E, Arber DA, eds. In: Hematopathology. Vol 53. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2011. p. :827-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a review of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:291-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uncommon histiocytic disorders: the non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:256-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Erdheim-Chester disease: a rare multisystem histiocytic disorder associated with interstitial lung disease. Am J Med Sci. 2001;321:66-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular involvement, an overlooked feature of Erdheim-Chester disease: report of 6 new cases and a literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004;83:371-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Disseminated juvenile xanthogranuloma. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, eds. WHO classification of tumors of haematopoeitic and lymphoid tissues (4th ed). Lyon: IARC Press; 2008. p. :366-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Erdheim-Chester disease. Clinical and radiologic characteristics of 59 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;75:157-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis with isolated CNS involvement: an unusual variant of Erdheim-Chester disease. Neuropathology. 2010;30:634-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuroradiologic aspects of Chester-Erdheim disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:735-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Case 25-2008: A 43-year-old man with fatigue and lesions in the pituitary and cerebellum. New Engl J Med. 2008;359:736-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of langerhans cell histiocytosis on fine needle aspiration cytology: a case report and review of the cytology literature. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:439518.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration of Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the lymph nodes: A report of six cases. Acta Cytol. 2002;46:753-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration cytology of Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (eosinophilic granuloma) of bone in children. Diagn Cytopathol. 1991;7:261-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma of bone by fine-needle aspiration with concurrent institution of therapy: a cytologic, histologic, clinical, and radiologic study of 27 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 1993;9:3-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Erdheim-Chester disease of the brain: cytological features and differential diagnosis of a challenging case. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;31:420-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Erdheim-Chester disease. A primary macrophage cell disorder. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:650-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunohistochemical evidence of a cytokine and chemokine network in three patients with Erdheim-Chester disease: implications for pathogenesis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:4018-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clonal status and clinicopathological feature of Erdheim-Chester disease. Pathol Res Pract. 2009;205:601-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clonal cytogenetic abnormalities in Erdheim-Chester disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:319-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of bone scintigraphy in patients with Erdheim-Chester disease. Clin Nucl Med. 2000;25:414-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Imaging of thoracoabdominal involvement in Erdheim-Chester disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1253-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Retroperitoneal infiltration as the first sign of Erdheim-Chester disease. Int J Urol. 2008;15:455-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- CT of Erdheim-Chester disease presenting as retroperitoneal xanthogranulomatosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1994;18:503-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Retroperitoneal xanthogranuloma in a patient with Erdheim-Chester disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:843-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Erdheim-Chester disease: clinical, radiologic, and histopathologic findings in five patients with interstitial lung disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:17-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic features of deep juvenile xanthogranuloma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1996;15:329-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Deep-seated congenital juvenile xanthogranuloma: report of a case with emphasis on cytologic features. Acta Cytol. 2007;51:473-6.

- [Google Scholar]