Translate this page into:

Diagnosis of metastatic fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

The fibrolamellar variant of hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC) is distinguished from other hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) by its unique clinical and pathologic features. Cytological features for this tumor on fine needle aspiration (FNA) of primary tumors have been described earlier. We present here a unique case of metastatic FL-HCC diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of mediastinal adenopathy. A 32-year-old woman with a history of oral contraceptive use presented with nausea and severe abdominal pain but no ascites or stigmata of cirrhosis. She had a past history of resection of a liver lesion. Serial computed tomography scans revealed mediastinal lymphadenopathy and the patient was referred for endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). A transesophageal EUS-FNA was performed and tissue was collected for cytological evaluation by an on-site pathologist with no knowledge of prior history. Based on morphology correlated with prior history received later, a final diagnosis of metastatic FL-HCC in the retrocardiac lymph node was rendered on the EUS-FNA samples. There are very few reports in the literature where a diagnosis of FL-HCC is rendered at unusual sites. This case highlights that EUS-FNA is a relatively non-invasive, rapid, accurate and effective modality in obtaining tissue from otherwise hard-to-reach areas. It also suggests that metastasis of FL-HCC can be observed in mediastinal nodes and that diagnosis based on cytological features can be rendered even when the tumor is identified at unusual locations.

Keywords

Metastatic fibrolamellar variant of hepatocellular carcinoma

endoscopic ultrasound guidance

fine needle aspiration

INTRODUCTION

The fibrolamellar variant of hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC) is distinguished from other hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) by its unique clinical and pathologic features. First described as “eosinophilic hepatocellular carcinoma with lamellar fibrosis” by Edmondson in 1956,[1] FL-HCC is typically diagnosed at a younger age than the age at which conventional HCC is diagnosed.[1–3]

According to Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data, FL-HCC accounts for approximately 1% of all primary liver cancer in the United States, with a mean age of 39 years at the time of diagnosis compared with 65 years for conventional HCC.[2] In this age group, other primary mass-forming lesions such as hepatocellular adenoma and focal nodular hyperplasia are more common. Most patients with FL-HCC do not have underlying liver disease, in contrast to the common associations of other HCC with cirrhosis and viral hepatitis.[13] and it is quite rare in regions of the world such as China and Japan, which show a high incidence of usual HCC.[3]

FL-HCC is detected at a localized stage at diagnosis and receives potentially curative resection or transplantation more commonly than conventional HCC.[2] FL-HCC patients also have better 1-year (73.3% vs. 26.0%) and 5-year (31.8% vs. 6.8%) survival when compared to all HCC.[2]

Cytopathologic features for this tumor on fine needle aspiration (FNA) of the primary tumors have been described earlier.[4–10] Diagnosis by FNA for this rare tumor, however, poses a unique set of challenges for unsuspecting pathologists, especially when this tumor is aspirated at unusual locations. We report here a unique case in which FL-HCC metastatic to the mediastinum was diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided FNA (EUS-FNA).

CASE REPORT

A 32-year-old woman with a history of oral contraceptive use presented with nausea and severe abdominal pain. She had no fever, weight loss or history of viral hepatitis. On examination, her spleen was not enlarged and there was no ascites or stigmata of cirrhosis. Her blood counts, including platelet count, were within reference ranges. She had a past history of resection of a liver lesion.

Serial computed tomography (CT) scans revealed small lesions at the base of the lungs that slowly increased in size. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy was also present and the patient was referred for EUS. EUS revealed a 41 mm x 31 mm lymph node in the lower paraesophageal/retrocardiac area. A transesophageal EUS-FNA was performed.

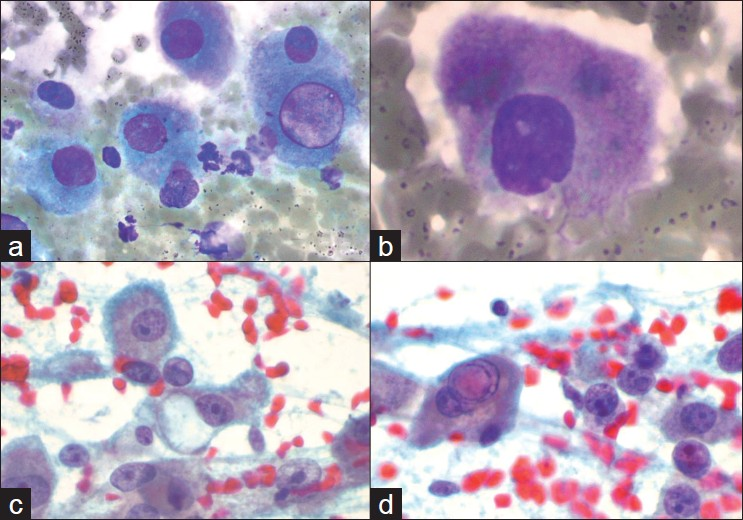

Air-dried, Diff Quik-stained slides and alcohol-fixed smears were prepared and the Diff Quik-stained slides [Figure 1] were examined on-site. The moderately cellular smears showed many individual cells and occasional aggregates of fibrous tissue. Individual cells were enlarged and had low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios, with abundant granular and eosinophilic cytoplasm. Frequently, the cells demonstrated sharply outlined cytoplasmic vacuoles as well as bile pigment in the cytoplasm. The nuclei were enlarged and had prominent nucleoli. Naked nuclei with prominent nucleoli were also noted. The possibility of a metastatic hepatic lesion was considered. The smears did not reveal some of the features associated with usual HCC, such as vessels traversing groups of hepatocytes, nor was the “basketing” pattern of endothelial cells surrounding groups of hepatocytes observed in these smears. FNA smears also revealed large polygonal cells with sharply outlined cytoplasmic borders with centrally placed nuclei. Unlike the neoplastic cells, these cells demonstrated small, pyknotic nuclei with regular nuclear membranes without prominent nucleoli or intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions. These cells represented contamination by surface esophageal mucosal cells. Other possibilities were also considered. Considering the unusual location for hepatocytes, further history was requested in the EUS suite from the referring clinician.

- Features of fibrolamellar variant of hepatocellular carcinoma seen in the fine needle aspirate material. Diff Quik-stained smears (a and b) show large discohesive tumor cells with abundant granular cytoplasm and low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios. A well-defined cytoplasmic pale body is seen in a. Papanicolaou-stained smears (c and d) demonstrate prominent nucleoli and naked nuclei. An intranuclear pseudoinclusion is also seen in d

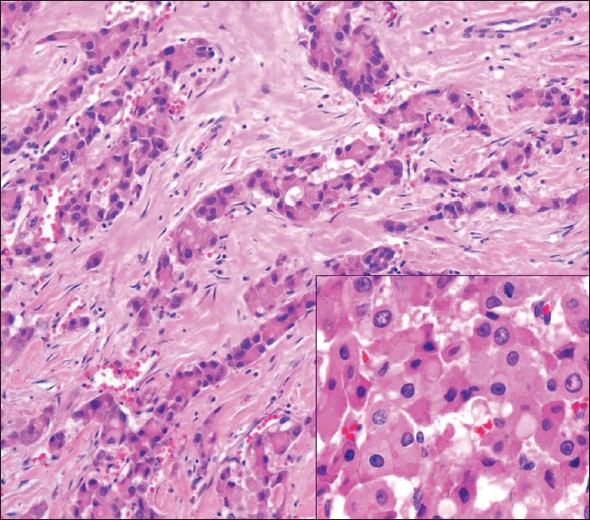

Additional, history suggested that 2 years ago a CT scan of the abdomen revealed a mass in the right lobe of the liver. Imaging study at the time did not reveal features of cirrhosis. Serum alpha-fetoprotein AFP levels were also within the reference range. A clinical diagnosis of hepatic adenoma was considered and the lesion was resected. Later, cells from the FNA sample were compared with the previously resected liver tumor that had revealed FL-HCC [Figure 2].

- Low-power view of fibrolamellar variant of hepatocellular carcinoma (hematoxylin and eosin [H and E]), with cords of tumor cells separated by bands of fibrous tissue. The inset shows a higher power image (H and E), which better demonstrates the abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, cytoplasmic pale bodies and nuclei with prominent nucleoli

A final diagnosis of metastatic FL-HCC in the retrocardiac node was rendered on the EUS-FNA samples.

DISCUSSION

This case highlights several challenges in the diagnosis of FL-HCC for which cytopathologic features have been previously described.[4–10] FNA specimens from these tumors generally show variably cellular smears with large, discohesive tumor cells with abundant granular and eosinophilic cytoplasm, centrally placed vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli and low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios. The so-called “pale bodies” in the cytoplasm represent non-specific cytoplasmic invaginations.[9] Intracytoplasmic hyaline globules (thought to be large lysosomes)[9] and intracellular bile pigment may be seen.[57] Intranuclear pseudoinclusions may be present and binucleation is not uncommon.[47] Bland, spindled cells arranged in parallel bands may also be seen, representing the bundles of collagen fibers and fibroblasts seen in the histologic sections.[4–10] The trabecular arrangement of conventional HCC is not seen.[410] Perez-Guillermo et al. described cytologic features of six cases of FL-HCC, and their morphometric studies showed that cell size, nuclear size and nucleolar size were significantly larger in FL-HCC cells than in those of conventional HCC.[4] These cells are approximately three-times the size of a normal hepatocyte and 1.6-times the size of a tumor cell from well-differentiated HCC.[4] Although FL-HCC is sometimes difficult to distinguish from conventional HCC, the young age of the patient did not favor conventional HCC. In addition, smears did not reveal the “basketing” pattern or traversing vessels that are commonly noted with conventional HCC.

Differential diagnosis from other primary liver lesions should include hepatocellular adenoma, focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatoblastoma. Other unusual tumors may also include metastatic carcinoma with prominent fibrosis and metastatic melanoma.[1356] This FNA, however, was not obtained from the primary lesion but, instead, represented a mediastinal lesion.

There are very few reports in the literature where a diagnosis of FL-HCC is rendered at unusual sites. Kunz et al. reported an unusual case in which the tumor extensively involved the intrahepatic bile ducts and the diagnosis was suspected on examination of biliary brushings, although a subsequent FNA better demonstrated the features of FL-HCC.[6] Use of FNA has been rarely reported in the diagnosis of metastatic FL-HCC.[78] Montero et al. recently reported a case of metastatic FL-HCC that presented with large bilateral ovarian metastases and was diagnosed by FNA of the left ovary.[7] Before the present case, there has been only one other report[8] to our knowledge that demonstrates metastasis of FL-HCC in the mediastinum. Unlike this prior report, FNA in the present case was performed under EUS guidance. Recognition of large polygonal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, enlarged, centrally placed nuclei and prominent nucleoli on FNA samples in the mediastinum raises several possibilities. Some of the more common lesions that could be included in the differential diagnoses are thymic carcinoma, paraganglioma, ganglioneuroma, germ cell tumor and metastatic melanoma. Use of a practical algorithm for mediastinal lesions, previously described by Bakdounes et al., is helpful for arriving at a diagnosis.[11]

In addition to the cytologic diagnosis of this uncommon tumor at a metastatic site, another unique aspect of our case is that the FNA was performed under EUS guidance. It is difficult to aspirate retrocardiac/lower paraesophageal lymph nodes with other imaging modalities. Prior to the advent of EUS, it would have required more invasive techniques to obtain tissue samples to document metastatic FL-HCC in these nodes. Thus, EUS provides better access to these hard-to-reach lymph nodes. Furthermore, our setting allows for immediate assessment of not only sample adequacy but also on-site diagnosis. EUS-FNA for the detection of metastatic malignancy is a very sensitive and specific modality.[12] Our results have also demonstrated an excellent concordance rate between on-site and final diagnosis.[13] This case also underscores the value of effective communication between the endoscopist and the on-site pathologist to ensure specimen adequacy as well as availability of relevant clinical information and also to provide rapid and accurate diagnosis for informed patient management.

In summary, we showed that EUS-FNA is a relatively non-invasive, rapid, accurate and effective modality to obtain tissue from otherwise hard-to-reach areas. This case also shows that diagnosis of FL-HCC can be made based on cytologic features even when the tumor is identified at unusual locations.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

No competing interest to declare by any of the authors.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved. All authors qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author. Each author participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Our institution does not require approval from the In-stitutional Review Board (IRB) for a case report without identifiers.

EDITORIAL / PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model(authors are blinded for reviewers and reviewers are blinded for authors)through automatic online system.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2011/8/1/2/76495

REFERENCES

- Fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver: A tumor of adolescents and young adults with distinctive clinico-pathologic features. Cancer. 1980;46:372-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is fibrolamellar carcinoma different from hepatocellular carcinoma? A US population-based study. Hepatology. 2004;39:798-803.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19:453-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic aspect of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma in fine-needle aspirates. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;21:180-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report with cytological features in a sixteen-year-old girl. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:568-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatocellular carcinoma - fibrolamellar variant: Cytopathology of an unusual case. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;26:257-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of massive bilateral ovarian metastasis of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Cytol. 2007;51:682-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration cytology and differential diagnoses of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma metastatic to the mediastinum: Case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;26:95-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytological features of fibrolamellar variant of hepatocellular carcinoma with review of literature. Cytopathology. 2002;13:179-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Cytol. 1985;29:867-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic usefulness and challenges in the diagnosis of mesothelioma by endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:503-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of deep-seated lymphoma and leukemia by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:703-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Providing on-site diagnosis of malignancy on endoscopic-ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspirates: Should it be done? Ann Diagn Pathol. 2007;11:176-81.

- [Google Scholar]