Translate this page into:

Estimation of iron overloads using oral exfoliative cytology in beta-thalassemia major patients

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Iron overload is a medical condition that occurs when too much of the mineral iron builds up inside the body and produces a toxic reaction. Thalassemia is a genetic disorder of hemoglobin synthesis, which requires regular blood transfusion therapy, and the lack of specific excretory pathways for iron in humans leads to iron overload in the body tissues. It is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in these patients. The estimation of iron levels in exfoliated buccal mucosal cells may provide a simple, noninvasive, and a safe procedure for estimating the iron overload by using the Perls’ Prussian blue stain.

Methods:

Smears were obtained from buccal mucosa of 40 randomly selected beta-thalassemia major patients and 40 healthy subjects as controls. Smears were stained with Perls’ Prussian blue method. Blood samples were taken for estimation of serum ferritin levels. Images of smears were analyzed using the software image J software version 1.47v and correlated with serum ferritin.

Results:

Perls’ positivity was observed in 87.5% of thalassemic patients with a positive correlation to serum ferritin levels.

Conclusion:

The use of exfoliative buccal mucosal cells for the evaluation of iron overloads in the body provides us with a diagnostic medium that is noninvasive, easy to collect, store, and transport, cost effective, and above all reliable.

Keywords

Iron overload

oral exfoliative cytology

Perls’ Prussian blue staining

thalassemia

INTRODUCTION

Mineral have a great diversity of uses within the human body. They are inorganic elements that are essential for maintaining the structural and regulatory functions of the body.[1] Among them, iron is a vital element that is a constituent of a number of important macromolecules, which are required by every human cell. Iron is essential to life because of its unusual flexibility to serve as both an electron donor and acceptor which means, if iron is free within the cell, it can catalyze the conversion of hydrogen peroxide into free radicals. Free radicals can cause damage to cellular membranes, proteins and DNA, a wide variety of cellular structures, and ultimately kill the cell.[2] To prevent that kind of damage, all life forms that use iron bind the iron atoms to proteins, which allow the cells to use the benefits of iron, but also limit its ability to do harm. The duality of iron, being both essential and toxic, led to the evolution of elaborate systems to ensure adequate iron levels while preventing iron overload.

Under normal circumstances, 1 mg of iron is absorbed by the human body per day. The concentration of iron in the human body is carefully regulated and normally maintained at approximately 40 mg Fe/kg body weight in women and approximately 50 mg Fe/kg body weight in men, distributed among functional, transport, and storage components.[3]

Since iron excretion from the body is limited and largely unregulated, regulation of total body iron is at the site of absorption.[4] The regulation of intestinal absorption of iron plays a crucial role to satisfy the needs of erythropoiesis. Considering the lack of specific excretory pathways for iron in humans, an iron overload may be precipitated by a variety of conditions such as increased iron absorption, as is seen in hemochromatosis or a frequent parenteral iron administration, as is seen in thalassemia.[1]

Ferritin, although present in the cells, cannot be visualized under a light microscope and it can be observed in the electron microscope only. Hemosiderin, because of its larger size, can be visualized under the light microscope as blue-colored granules in the cytoplasm of the cell when stained with Perls’ Prussian blue. Hemosiderin is supposed to be formed when the quantity of iron exceeds the apoferritin storage pool or as the ferritin molecule ages.[5]

Perls’ Prussian blue reaction is considered to be the first classical histochemical reaction carried out for iron and is widely applied in the field of hematology. Treatment with a dilute acid is an essential preliminary in the performance of the Prussian blue reaction. By this means, the ferric iron is liberated from unreactive loose combinations with proteins such as hemosiderin. We have applied this technique to exfoliated buccal mucosal cells, considering the fact that the exfoliated cells would reflect the iron overload status of the body.

As more stress is being laid on the development of noninvasive techniques for diagnosis, its advantage is charting the prognosis of chronic diseases such as thalassemia which is immense. Serum ferritin level is an established method of evaluating the iron overload status of the tissues due to repeated blood transfusions. With no known efficient mechanisms for secretion of iron, every transfusion adds to the iron loads in tissues and subsequently leads to serious side effects such as cardiomyopathy, liver cirrhosis, and damage to nervous system. Review of the literature shows only few studies that used exfoliative cytology as a major tool to determine the iron overloads; however, all those studies determine the qualitative assessment of iron overload; in our study, we attempted to establish Perls’ Prussian blue stain, as a reliable diagnostic and prognostic exfoliative cytological technique for monitoring serum iron levels in beta-thalassemia major patients undergoing repeated blood transfusions. We have also tried to correlate between serum ferritin levels and iron granules present in exfoliated buccal mucosal cells.

METHODS

This study was carried out at the Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Swami Devi Dyal Hospital and Dental College, Barwala, Panchkula, after obtaining approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee. The study population was drawn from patients reporting to the outpatient department of Mukand Lal Civil Hospital, Yamunanagar. Study group consisted of 40 beta-thalassemia major patients who have undergone a minimum of 15 transfusions. Control group consisted of 40 normal age- and sex-matched individuals without any clinical and laboratory evidence of iron deficiency anemia, acute and chronic liver damage, malignancy, and megaloblastic anemia.

The patients from the study group and the control group were asked to rinse their mouth with distilled water. The buccal mucosa of the patients were scraped with a wet wooden spatula and smeared onto glass micro slides. The smear was fixed immediately in 70% ethanol for 1 h and then stained with Perls’ staining kit. The kit consisted of potassium ferrocyanide, which reacts with the ferritin in the cells to form a blue-colored compound. This blue-colored compound is visible under the light microscope as blue granules. This staining reaction is referred to as Perls’ Prussian blue reaction. Neutral red was used as the nuclear stain.

The stained smear was examined under the light microscope through the transmitted light at ×40 magnification to study the presence or absence of blue-colored granules in the cells.

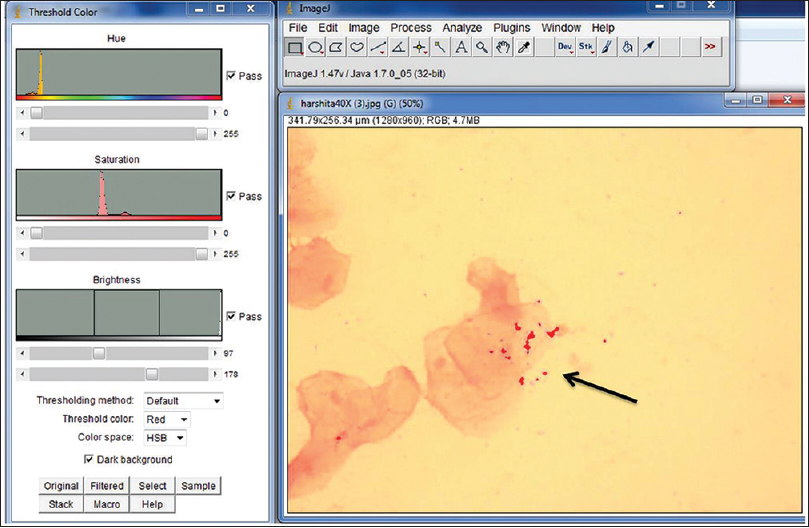

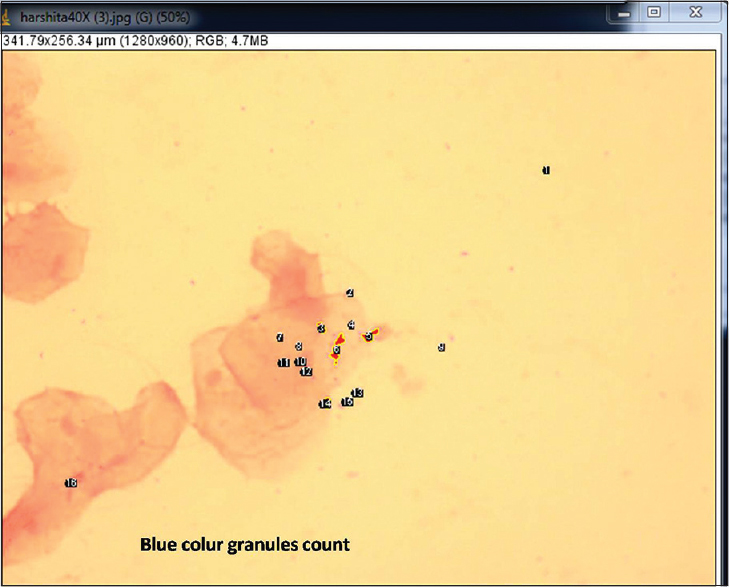

Smears were observed under microscope and eight fields were randomly selected. Overlapping cells were not included in the study. The images were captured with a camera attached to the microscope. All the images of the cells were captured with a ×40 achromatic objective. Images thus captured were stored on the computer and analysis was done using the software image J software version 1.47v (Java-based image processing program developed at the National Institutes of Health). The software works on the principle of identifying threshold color (blue in our case). Outlines of the granules were traced automatically by choosing the threshold color. The measurements were carried out using measurement tool and were done in microns. The area, perimeter, count, size, and percentage areas were recorded.

Recording serum ferritin

Blood samples were withdrawn from antecubital vein both for the study as well as control group for the estimation of serum ferritin levels. The sample was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min to get clear supernatant. The test cups (Tosoh Bioscience AIA-PACK Test Cups – FER [ferritin]) and Hitachi cups which contained sample were loaded in Tosoh Bioscience Autoanalyzer (ELISA BASED). Once samples and test cups are loaded, the results can be obtained in 20 min on the reading board of the analyzer.

RESULTS

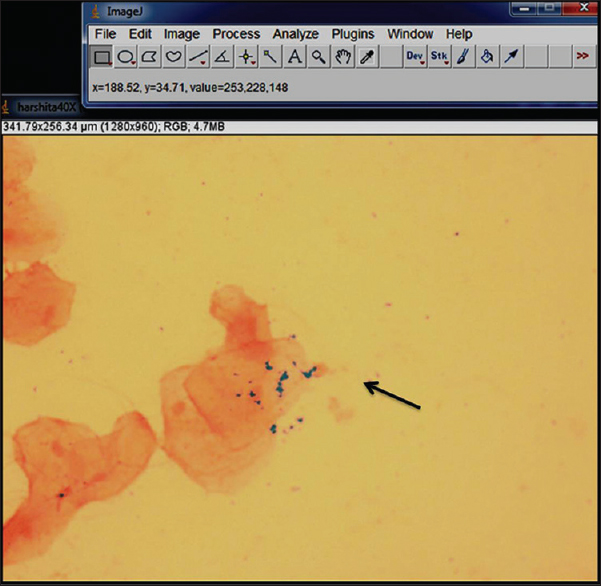

The presence of blue-colored granules in the exfoliated cells of the buccal mucosa on staining with Perl's Prussian blue stain was evaluated and co-related with serum ferritin levels [Figure 1].

- Cells depicting iron granules in the form of Perls’ Prussian blue reaction

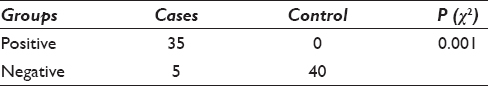

A quantitative analysis of the blue granules was carried out to evaluate their counts, percentage area, perimeter, and average size [Figures 2 and 3]. The values of qualitative analysis of iron granules for two groups, i.e., cases and control were obtained. Values were found to be positive in 35 (87.5%) out of 40 patients and was negative for 5 (12.5%) of the cases. All the control cases were negative which makes 100%. The value of Chi-square test used for computing P value showed that the value was highly significant at the level of 0.001 [Table 1]. These values show that the distribution of the iron overload between the thalassemia and the control patients was statistically significant.

- Blue color granules count

- Blue-colored iron granules by applying color threshold gets selected as a red area

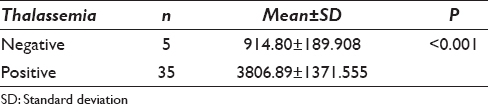

The mean values and standard deviation for serum ferritin of negative and positive values of Perl's Prussian blue reaction in cases [Table 2]. Five patients out of 40 showed negative results. The mean value of serum ferritin in positive and negative Perl's Prussian reaction was 3806.89 and 914.80 ng/ml, respectively. The P value of nonparametric test (i.e. Mann–Whitney test) which was applied to the ferritin levels values for negative and positive values of Perl's Prussian blue reaction in the cases was found to be highly significant (P < 0.001).

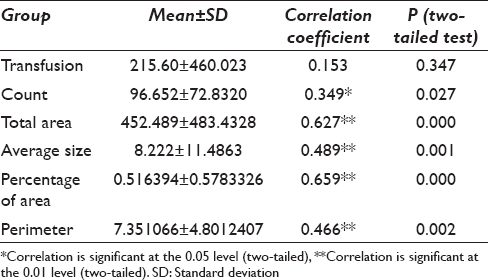

Correlation of serum ferritin with transfusion, count, total area average size, percentage area, and perimeter was done [Table 3]. On applying two-tailed test, it was found that the results for counts were significant at 0.027 whereas all others were found to be significant at the level of 0.01 except transfusions which was statistically insignificant. Spearman's rho ratio was used for finding the correlation between the serum ferritin with transfusion, count, total area average size, percentage area, and perimeter. The results showed that serum ferritin was significantly correlated to counts (349 [P < 0.05]). Highly significant correlations were found among serum ferritin and total area (0.627 [P < 0.01]), average size (489 [P < 0.01]), percentage area (0.659 [P < 0.01]), and perimeter (0.466 [P < 0.01]). The association of serum ferritin levels with number of transfusions was nonsignificant (P > 0.05). These results show that an increasing serum ferritin level is significantly associated with the area, perimeter, counts, percentage area, and average size of the iron particle.

DISCUSSION

The toxic effects of the chronic iron deposition in the tissues have been recognized for many years in the idiopathic hemochromatosis and in the transfusion hemosiderosis conditions of thalassemia. Iron accumulation in beta-Thalassemia major patients depends upon the number of blood transfusions given. One unit of blood contains 250 ml of red blood cells and 250 mg of iron. Signs of clinical toxicity become apparent, when body iron reaches 400–1000 mg/kg body weight. Signs of iron overload can be usually seen after 10–12 transfusions.[6]

The iron status of patients with transfusional iron overload can be studied by several methods, none of which are completely satisfactory. The use of two or more indices of iron status will usually be needed to define the amount of iron and its distribution to different organs. In general, two types of methods may be differentiated: The direct methods based on the detection of iron within the tissue, performed either by biopsy or noninvasive methods, and indirect tools, for example, the serum ferritin concentration or iron saturation of serum transferrin.

In our study, exfoliated cells from the buccal mucosa of 40 beta-Thalassemia major patients comprising the study group undergoing a minimum of 15 transfusions and a control group containing 40 normal individuals who had no confirmed acute and chronic liver damage, malignancy, and megaloblastic anemia were considered and the smears obtained were stained with Perls’ Prussian blue stain.

Out of 40 thalassemia patients, 35 patients (87.5%) showed iron positivity in the Perls’ Prussian blue reaction, which was statistically significant (P < 0.05) as compared to controls [Table 1]. Five of 40 thalassemic patients showed the negative results. This shows a strong association between the thalassemia patients who were undergoing repeated blood transfusions and an oral mucosal iron overload.

Gururaj and Sivapathasundaram performed a similar type of study on ten patients, which revealed a positivity for the Perls’ Prussian blue reaction in all the ten cases.[7] The present study was also in accordance with Nandaprasad et al., in which the exfoliated cells from the buccal mucosa in 65 of the 100 thalassemia patients revealed positivity for the Perls’ Prussian blue reaction.[8] A recent study by Chittamsetty et al.,[1] also showed 72.5% positivity for iron granules in buccal mucosal cells in beta-thalassemia major patients. Study by Bhat et al., also showed positivity for iron granules in 43 out of 60 beta-thalassemia major patients.[9] The control group were negative for the Perls’ Prussian blue reaction in all the above-mentioned studies which were in accordance to our study.

In the present study, an attempt was made to correlate the presence of iron in the exfoliated oral epithelial cells with that of the serum ferritin levels in the patients with thalassemia. It was found that the mean value at which the Perls’ Prussian reaction seem to be positive and negative in oral epithelial cell was found to be 3806.89 ng/dl and 914.80 ng/dl, respectively [Table 2]. It was observed that as the serum ferritin levels increased, the iron overload in the oral mucosal cells of the thalassemia patients also increased, which was statistically significant (P < 0.001). This indicates that the positive staining in exfoliated buccal cells can be used for diagnosing changes in serum ferritin levels and thus, indicating iron overload in the body tissues.

The exact reason for positivity of Perls’ Prussian blue staining in thalassemic patients and a highly significant correlation to serum ferritin levels can be hypothetically explained on the basis of iron metabolism. The excess amount of iron in the blood that gets accumulated in various tissues may depend upon various factors including the formation of iron storage pool. The amount of apoferritin and therefore, ferritin formed in exfoliated buccal cells, may vary as well as there may be variation in the amount of hemosiderin formed, which may invariably affect the Perls’ positivity. When iron overload results from the increased catabolism of erythrocytes as in the case of transfusional iron overload, iron accumulates in reticuloendothelial macrophages first and only later spills over into parenchymal cells.[2]

With advancements in the field of quantitative oral exfoliative cytology, interest in oral cytology has once again emerged in the diagnosis of various lesions. Computer-assisted morphometric analysis of exfoliative cytology specimens has improved the ability to accurately measure various cell parameters. The results of image analysis which was done to quantitate the iron levels objectively. The mean value and standard deviation of number of transfusion, serum ferritin level, iron granule count, total area, average size, percentage area, and perimeter of iron granules in beta-thalassemia major patients were assessed with the help of an image Analysis Software (Q-Capture pro 7) from Acal Bfi UK; and image J software version 1.47v and co-related with serum ferritin levels. Significant co-relations of the parameters of iron granules were observed with serum ferritin levels [Table 3]. However, a correlation with number of blood transfusions was not significant, and this could be ascribed to the factors contributing to variations in the serum ferritin levels as described earlier. This proved that the amount of iron granules present in exfoliated buccal mucosal cells as detected by an objective parameter such as image analysis software could be useful in the evaluation of body iron levels during prolonged follow-up of patients.

From our results, we observed that the presence of iron granules as demonstrated by Perls’ Prussian blue stain in exfoliative cells of the buccal mucosa can be reliably used to diagnose an overload of iron in body tissues. Considering the simplicity and acceptability of exfoliative cytology methods, further studies can establish this noninvasive procedure as an ideal screening and diagnostic tool in all patients undergoing repeated blood transfusions to assess iron overload.

CONCLUSION

Our results proved that the presence of iron granules as demonstrated by Perls’ Prussian blue stain in exfoliative cells of the buccal mucosa can be reliably used to diagnose an overload of iron in body tissues. Furthermore, the image analysis was used to objectively correlate the amount of iron granules with serum ferritin levels. Our study showed a significant correlation between serum ferritin levels with granule counts, their total area, percentage area, and perimeter. This proved that the amount of iron granules present in exfoliated buccal mucosal cells as detected by an objective parameter such as image analysis software could be useful in the evaluation of body iron levels during prolonged follow-up of patients. The use of exfoliative buccal mucosal cells for the evaluation of iron overloads in the body provides us with a diagnostic medium that is noninvasive, easy to collect, store and transport, cost effective, and above all reliable.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

‘The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests’.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE.

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

Dr. Swati Leekha planned the study design and carried the out the sampling, staining, image analysis and alignment and drafted the manuscript. Dr. Amit Nayar helped in standardization of stains, selection of samples and editing of the manuscript. Dr. Preeti Bakhshi conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and contributed in patient selection, and getting permissions from the hospital. She also play role in final editing of the study. Dr. Aman Sharma and Dr. Swati plays role in drafting and alignment of the study. Dr. Sugandhi Soni has contribution in statistical analysis.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from Institutional ethical committee. Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

None.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Dr. Vijay Dahiya, CMO and Head, Thalassemia ward MLN, Civil Hospital Yamunanagar, Dr. Avinash Jain MD Pathology and Dr. Nature Bakshi MS surgery for their constant support throughout the study.

REFERENCES

- A non-invasive technique which demonstrates the iron in the buccal mucosa of sickle cell anaemia and thalassaemia patients who undergo repeated blood transfusions. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1219-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iron absorption and bioavailability: An updated review. Nutr Res. 1998;18(3):581-603.

- [Google Scholar]

- Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. (4th ed). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1996.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of iron overload on endocrinopathies in patients with beta-thalassaemia major and intermedia. Endokrynol Pol. 2012;63:260-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Demonstration of iron in the exfoliated cells of oral mucosa. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2003;7:37-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oral exfoliative cytology in beta thalassaemia patients undergoing repeated blood transfusions. Internet J Pathol. 2009;10

- [Google Scholar]

- Demonstration of iron in exfoliated buccal cells of ß-thalassemia major patients. J Cytol. 2013;30:169-73.

- [Google Scholar]