Translate this page into:

Merkel cell carcinoma presenting as malignant ascites: A case report and review of literature

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

The most common site of metastasis to ascitic fluid in females is from a mullerian (ovarian) primary, whereas in males it is from the gastrointestinal tract. Metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) to the ascitic fluid is extremely rare and may present as a diagnostic challenge on effusion cytology. In a review of the literature, there are only two case reports of metastatic MCC in pleural effusion. To the best of our knowledge, we present the first cytological diagnosis of MCC metastatic to the ascitic fluid. We describe the cytologic findings as well as the immunohistochemical stains supportive of the diagnosis. Given the fatal prognosis of this tumor compared to melanoma and rarity of its occurrence in ascitic fluid, awareness of this tumor and use of immunohistochemical stains are critical in arriving at the diagnosis.

Keywords

Ascitic fluid

merkel cell carcinoma

metastasis

INTRODUCTION

Peritoneal fluid cytology plays an important role in the diagnosis of metastatic tumors, especially in patients with a previously documented primary neoplasm. However, in some cases, a malignant effusion is the first manifestation of an occult malignancy. Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, and very aggressive cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor of the skin associated with high-risk of loco-regional and distant metastasis.[1] Although cases of metastatic MCC diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration have been reported,[2] the incidence of metastatic MCC in effusions is extremely uncommon. There are only two case reports of MCC metastatic to the pleural fluid.[34] To our knowledge, there have been no reports of MCC in ascitic fluid. Here, we describe the first case of MCC metastatic to the ascitic fluid. We focus on the cytologic findings, immunohistochemical stains, and differential diagnosis.

CASE REPORT

The patient is a 46-year-old woman who presented with abdominal pain and new onset of ascites. There was no known prior diagnosis of MCC. Computerized tomography of the abdomen showed a cirrhotic liver with diffuse heterogeneous enhancing lesion at the porta hepatis measuring 4 cm × 2.7 cm and a 3.6 cm × 6.7 cm arterially enhancing lesion in hepatic segment IVa. The portal, superior mesenteric, and splenic veins were patent and normal in caliber. No gastroesophageal varices were present. A moderate amount of ascites was present. There were enlarged periportal, gastrohepatic, peripancreatic, retroperitoneal, and mesenteric lymph nodes seen. The largest node in the periportal region measured 2.8 cm x 2.7 cm. The radiologic impression was cirrhosis with multifocal arterially enhancing hepatic lesions and heterogeneous appearance of the liver concerning for diffusely infiltrating hepatocellular carcinoma with upper abdominal and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy likely representing metastatic disease. The tumor markers were within normal limits (AFP 9.2 ng/ml and CEA 1.3 ng/ml). The patient underwent paracentesis.

Cytologic findings

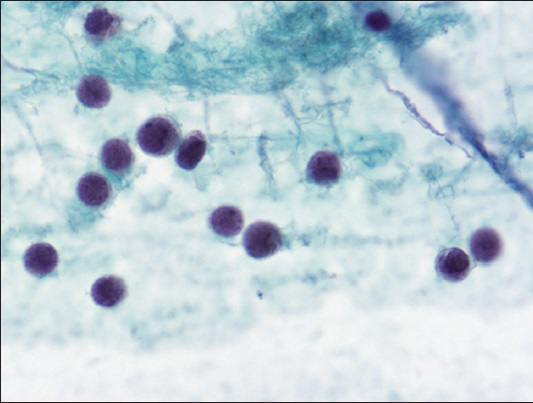

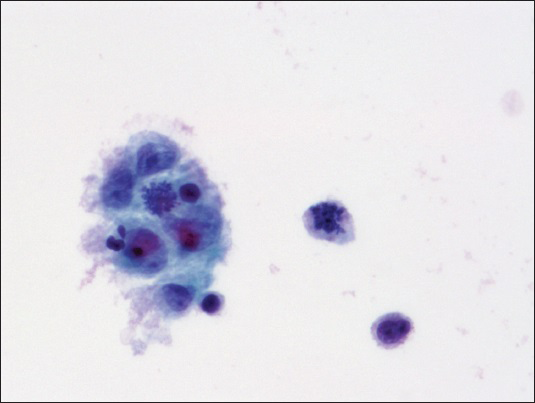

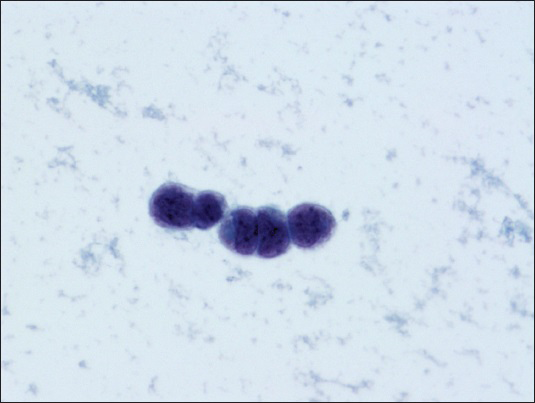

The thin prep smears stained with Papanicolaou showed malignant cells arranged singly [Figure 1], in clusters [Figure 2] and occasional single-file pattern [Figure 3]. The individual cells showed round to oval nuclei, irregular nuclear borders, stippled chromatin pattern, inconspicuous nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm [Figure 1]. Mitotic figures were identified [Figure 2]. Occasional nuclear molding was present.

- Loosely dispersed malignant cells with round to oval nuclei, irregular nuclear borders, stippled chromatin pattern, inconspicuous nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm (Papanicolaou, ×600)

- Malignant cells arranged in clusters with occasional mitotic figures (Papanicolaou, ×600)

- Malignant cells arranged in single-file pattern with focal nuclear molding (Papanicolaou stain, ×600)

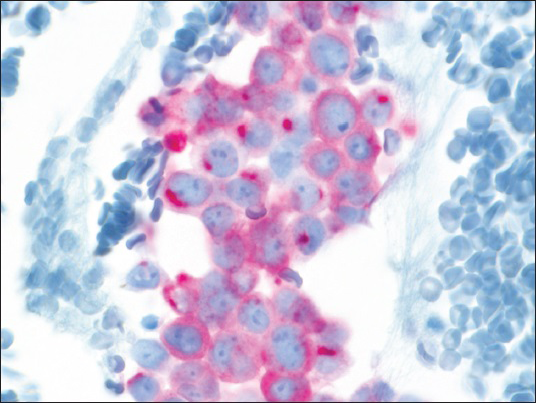

Histologic and immunohistochemical findings

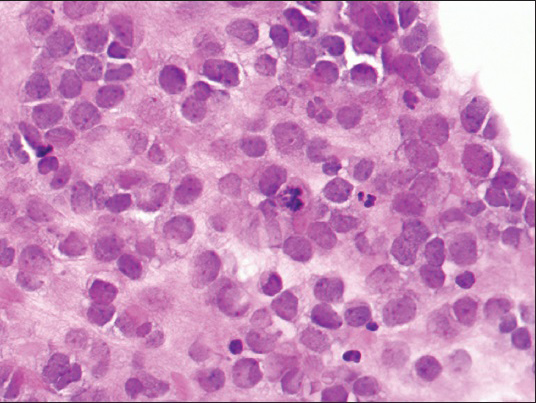

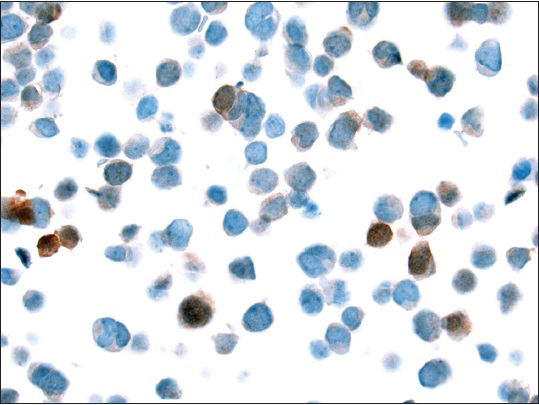

The cell block preparation stained with hematoxylin and eosin showed loosely dispersed malignant cells with high nucleus to cytoplasmic ratio, fine to clumped chromatin pattern, occasional small inconspicuous nucleoli, irregular nuclear borders, and scant eosinophilic cytoplasm [Figure 4]. Occasional mitotic figures were identified. Immunohistochemical stains showed the tumor cells were immunoreactive for AE1/AE3, CK20 [Figure 5], chromogranin, synaptophysin, and Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) monoclonal antibody (CM2B4) [Figure 6]. The tumor cells were negative for CK7, CEA, B72.3, CD45, CD138, CD56, TTF-1, BerEp4, S-100, Hep Par1, CK5/6, and calretinin.

- Cell block showing loosely dispersed malignant cells with high nucleus to cytoplasmic ratio, fine to clumped chromatin pattern, occasional small inconspicuous nucleoli, irregular nuclear borders, and scant eosinophilic cytoplasm (H and E, ×400)

- Tumor cells with “dot-like” rim pattern of staining with CK20 (×400)

- Few tumor cells showing nuclear staining with Merkel cell polyomavirus monoclonal antibody (CM2B4) (×400)

DISCUSSION

MCC is a rare and aggressive neuroendocrine tumor of the skin initially described in 1875 by Merkel.[5] It is often seen on the head and neck region in elderly patients. The cell of origin was initially believed to be mechanoreceptor. However, recent findings suggest the possibility of an epidermal stem cell origin.[6] The risk factors associated with MCC include ultraviolet-exposure, treatment with psoralen plus ultraviolet light therapy, and immunosuppression (patients with HIV, lymphoma, status postsolid organ transplantation, and patients on immunosuppressive therapy).[789] Given that MCC is often seen in elderly and immunocompromised patients, an infectious etiology was hypothesized as a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of MCC. This lead to the discovery of Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) in 2008 by Feng et al.[10] In their study, six of eight MCPyV positive MCCs had viral DNA integrated within the tumor genome in a clonal pattern. Their results support that Merkel cell virus infection and genome integration occurred in the tumor prior to clonal expansion of tumor cells.

MCC has a predilection for the head and neck region and metastasis to the cervical, and the axillary lymph nodes are common. Distant metastases to other sites such as brain, heart, thoracic spine, and parotid have been reported.[11121314] In approximately 60% of metastases, there is a known history of primary MCC. Hence, MCC can be diagnosed on fine needle aspiration with the support of immunohistochemical stains.[2] However, in cases with no known primary MCC, as seen in this case, it can be a difficult diagnosis.

Metastatic MCC to effusions can be a diagnostic challenge. To date, there are only two reports of metastatic MCC to the pleural fluid.[34] The first case was from a patient with a prior diagnosis of MCC involving the left great toe who presented with extensive metastasis occurring over 20 years after primary resection and treatment.[4] The pleural fluid was highly cellular and showed single to loosely cohesive clusters of small cells approximating the size of a large lymphocyte or lymphoblast. The individual cells showed round to oval hyperchromatic nuclei, smooth nuclear borders, finely granular chromatin, tiny nucleoli, and scant to absent cytoplasm. Tumor cells arranged in pseudoglandular or rosette-like structures were also present. Electron microscopy showed cytoplasmic microfilaments and numerous dense-core peripheral neurosecretory granules. No immunohistochemical stains were performed. The second case of MCC in the pleural fluid was from a 77-year-old woman who initially presented with a right buttock mass.[3] The cytologic findings showed single cells with abundant round, basophilic nuclei, granular “salt and pepper” nuclear chromatin, and many mitosis. Immunohistochemical stains performed on the cell block showed characteristic “dot-like” rim pattern of staining with CK20. Although, our cytologic findings were similar to these two reported cases, our other findings were the presence of occasional nuclear molding and “single file” pattern which could mimic either small cell carcinoma in the former or lobular breast carcinoma in the latter. Immunohistochemical stains supportive of the diagnosis will include dot-like positivity for cytokeratin, CK20, and neuroendocrine markers (chromogranin, synaptophysin, and CD56). In 2009, a monoclonal antibody (CM2B4), generated against a predicted antigenic epitope on the MCV T-antigen was found useful in the diagnosis of MCC.[15] In their study, CM2B4 was positive in 68% of metastatic MCC and in 86% of primary MCC. Nuclear staining of tumor cells ranging from 5% to >75% was interpreted as positive. A caveat is that in neuroendocrine tumors of the skin associated with squamous cell carcinoma, CM2B4 stain is negative.

Differential diagnoses

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is a rare aggressive body cavity based non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma caused by Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus/Human herpes virus type 8 (HHV8). It is often seen in young to middle-aged HIV-positive patients and rarely in immunocompromised patients such as organ transplant recipients and older patients.[16] Most of the PELs occur exclusively in the pleural, pericardial or abdominal cavities. The cytology preparations are very cellular and consists of large atypical lymphocytes with centrally to eccentrically located nuclei (plasmablastic), irregular nuclear borders, coarse chromatin pattern, prominent nucleoli, and abundant basophilic cytoplasm.[17] Apoptotic bodies and nuclear debris can also be seen. Immunohistochemical stains will show positivity of the tumor cells for CD45, HHV8 latent nuclear antigen, and Epstein-Barr virus encoded RNA.

Invasive lobular breast carcinoma has a known predilection to metastasize to the gastrointestinal tract, gynecologic tract, peritoneum, and retroperitoneum. Hence, it could present clinically as ascites. In a study by Antic et al., they described the tumor cells in the ascitic fluid, as diffusely dispersed in a single-cell pattern, some of which resembled mesothelial cells.[18] These individual cells showed mild to moderate nuclear atypia with rare tumor cells showing the presence of targetoid mucin. Immunohistochemical stains will show the tumor cells to be positive for BerEp4, B72.3, MOC 31, ER, and will be negative for calretinin, mesothelin, WT-1, and CK5/6. GATA3, a recently reported sensitive and specific marker for breast carcinoma has been reported to show nuclear positivity in 90% of metastatic breast carcinoma in serous effusion and could be helpful, especially in cases of triple negative breast carcinomas.[19]

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) which belongs under the umbrella of round cell sarcoma is a tumor of unknown histogenesis. It is a highly fatal malignant tumor seen in a young age group (15–35 years of age) and often intra-abdominal in location or within the pelvic peritoneum.[20] It may spread along the serous surfaces and could present clinically as ascites.[21] In a paper by Oliveira et al., the tumor cells in the ascitic fluid were described as cohesive poorly differentiated small cells with scant cytoplasm, reticulated chromatin, and prominent nucleoli.[21] Based on cytology alone, it is difficult to differentiate DSRCT from other small round cell tumors. Useful immunohistochemical stains will show positivity for WT-1 and dot-like paranuclear staining pattern for keratin and desmin. Demonstration of the characteristic t (11;22)(p13;q12) either by using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction or fluorescence in situ hybridization will be supportive of the diagnosis.

Malignant melanoma in effusions could present as predominantly discohesive cells with round to oval, hyperchromatic and eccentrically located nuclei with prominent nucleoli. In a paper by Beaty et al., a high nucleus to cytoplasmic ratio was seen in 3% of their cases.[22] In 69% of their cases, fine to black to dark-blue cytoplasmic melanin pigment was observed. Nuclear pseudoinclusions were present only in a quarter of their cases. Immunohistochemical stains will show positivity of the tumor cells for HMB-45, S-100, and MART-1. In a study by Vrotsos and Alexis, SOX-10 appears to be a sensitive and specific antibody for detection of metastases to a sentinel lymph node.[23] However, it's utility in malignant effusions have not been reported.

In summary, MCC can rarely metastasize to the ascitic fluid and the cytologic findings could mimic “small round blue cell” tumors on cytology. Familiarity with this tumor and use of immunohistochemical stains will be extremely helpful in clinching the diagnosis of this fatal and aggressive tumor.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE.

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work. DA provided substantial contributions to conception and design; MPN was responsible for drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and TH performed the final approval of the version to be published.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Since this is a case report without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from the Institutional Review Board.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

DSRCT - Desmoplastic small round cell tumor

HHV8 - Human herpes virus type 8

MCC - Metastatic Merkel Cell Carcinoma

MCPyV - Merkel Cell Polyomavirus

PEL - Primary Effusion Lymphoma.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and the highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Kathleen Flannigan, who critically proof-read the article.

REFERENCES

- Merkel cell carcinoma from 2008 to 2012: Reaching a new level of understanding. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39:421-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Merkel cell carcinoma challenge: A review from the fine needle aspiration service. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:179-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma in a malignant pleural effusion: Case report. Cytojournal. 2004;1:5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytology of metastatic neuroendocrine (Merkel-cell) carcinoma in pleural fluid. A case report. Acta Cytol. 1985;29:397-402.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tastzellen and tastkoerperchen bei den hausthieren und beim menschen. Arch Mikrosc Anat. 1875;11:636-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunohistochemical analyses point to epidermal origin of human Merkel cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 2014;141:407-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell carcinoma: Critical review with guidelines for multidisciplinary management. Cancer. 2007;110:1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel-cell carcinomas in patients treated with methoxsalen and ultraviolet A radiation. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1247-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emerging and mechanism-based therapies for recurrent or metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2013;14:249-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096-100.

- [Google Scholar]

- Loss of cytokeratin 20 and acquisition of thyroid transcription factor-1 expression in a Merkel cell carcinoma metastasis to the brain. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:904-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thoracic spinal metastasis of Merkel cell carcinoma in an immunocompromised patient: Case report. Evid Based Spine Care J. 2013;4:54-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Secondary Merkel cell carcinoma manifested in the parotid. Case Rep Dermatol Med 2013 2013:960140.

- [Google Scholar]

- Merkel cell polyomavirus expression in Merkel cell carcinomas and its absence in combined tumors and pulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1378-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary effusion lymphoma in an elderly patient effectively treated by lenalidomide: Case report and review of literature. Blood Cancer J. 2014;4:e190.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tumor type and single-cell/mesothelial-like cell pattern of breast carcinoma metastases in pleural and peritoneal effusions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:311-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- GATA3: A promising marker for metastatic breast carcinoma in serous effusion specimens. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122:307-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration in desmoplastic small round cell tumor: A report of 10 new tumors in 8 patients with clinicopathological and molecular correlations with review of the literature. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122:386-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- From conventional fluid cytology to unusual histological diagnosis: Report of four cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:348-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effusion cytology of malignant melanoma. A morphologic and immunocytochemical analysis including application of the MART-1 antibody. Cancer. 1997;81:57-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Can SOX-10 or KBA.62 Replace S100 Protein in Immunohistochemical Evaluation of Sentinel Lymph Nodes for Metastatic Melanoma? Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2015 Jan 21 [Epub ahead of print]

- [Google Scholar]