Translate this page into:

Sclerosing hemangioma: A diagnostic dilemma in fine needle aspiration cytology

*Corresponding author

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Sclerosing hemangioma of the lung is a benign neoplasm with a widely debated histogenesis. It has a polymorphic histomorphology characterized by a biphasic cell population of “surface cells” and “round cells” arranged in four general patterns: Papillary, solid, angiomatous, and sclerotic. This variability in histomorphology makes it difficult to diagnose sclerosing hemangioma by fine needle aspiration (FNA). We present a case of sclerosing hemangioma diagnosed on FNA with immunohistochemistry performed on an accompanied cell block. The clinical presentation, cytomorphology, immunohistochemistry, and differential diagnoses are discussed.

Keywords

Cytology

fine needle aspiration

lung

pneumocytoma

sclerosing hemangioma

INTRODUCTION

Sclerosing hemangioma of the lung is an uncommon neoplasm that was first described by Liebow and Hubbell.[1] Morphological similarities between the “sclerosing hemangioma” of the skin and this lesion coined its name. Hubbell described it as a biphasic tumor with variable morphology commonly displaying marked vascular proliferation associated with sclerosis, papillary infoldings that obliterate distal air spaces and an atypical proliferation of tumor cells lining these air spaces. The name is a misnomer since most immunohistochemical and electron-microscopic studies suggest an epithelial origin for the tumor cells.[2] Various authors have proposed other names for this tumor to reflect the current literature, including benign sclerosing pneumocytoma, papillary pneumocytoma, and sclerotic hemorrhagic alveolar-cell tumor of the lung.[345]

Sclerosing hemangioma is a diagnostic challenge to the cytopathologist due to its variable histology. The cytologic findings vary depending on the area sampled. There are no large studies, but only isolated case reports regarding the cytologic diagnosis of sclerosing hemangioma, which show that it is often misdiagnosed on fine needle aspiration (FNA) specimens.[26789101112131415] We herein describe a case of sclerosing hemangioma diagnosed on FNA with immunohistochemistry performed on accompanied cell block and review the clinicopathologic findings of this neoplasm.

CASE REPORT

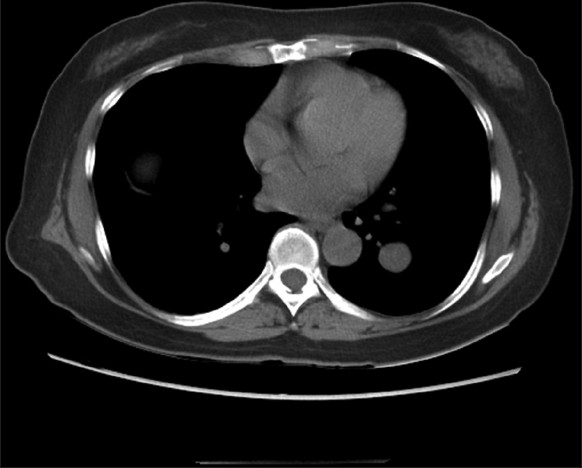

A 56-year-old nonsmoking Chinese (Cantonese) woman presented with an incidental solitary left lower lobe lung nodule identified on computed tomography (CT) at an outside facility. The nodule was well-circumscribed and measured 2 cm in greatest dimension. On CT scan, the nodule displayed low attenuation and focal areas of calcification [Figure 1]. The clinical impression was a pulmonary neoplasm of uncertain behavior, likely benign. The patient was referred to our institution for further work up. CT-guided FNA and core needle biopsies were performed.

- Noncontrast computed tomography scan of the chest showing a 2 cm round soft tissue mass with smooth regular margin in the left lower lobe

Cytology findings

Three FNA passes were done using 23 gauge needles. Smears were stained with Diff-Quik and Papanicolaou stains. Needles rinses were collected in a tube in RPMI solution for cell block preparation.

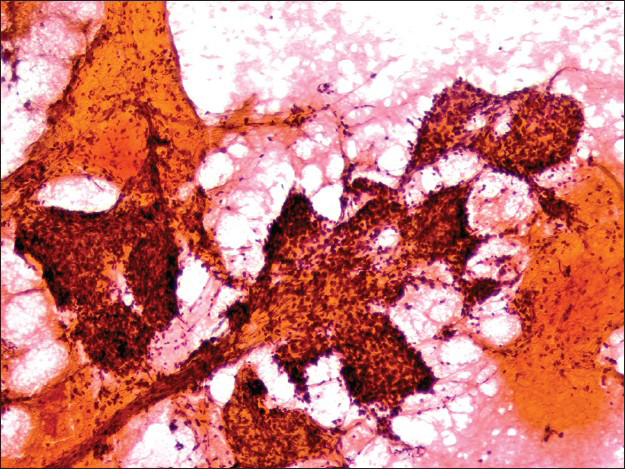

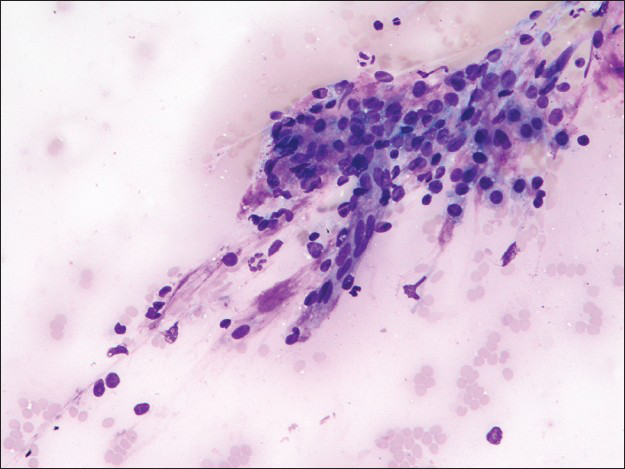

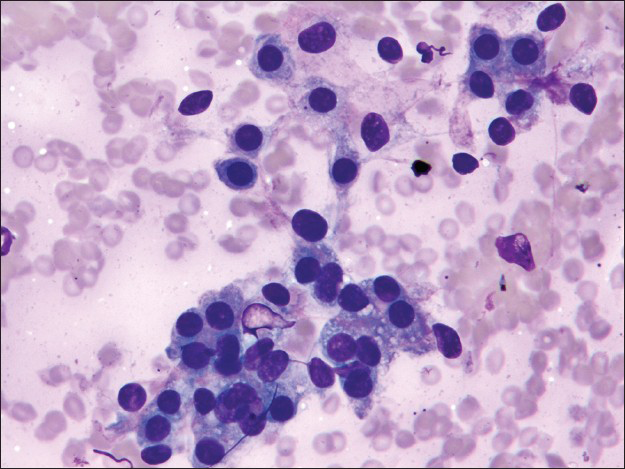

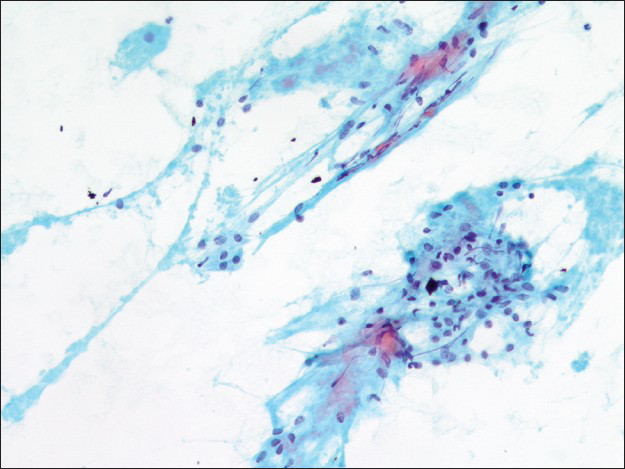

The first pass produced predominantly blood admixed with a few alveolar macrophages. The second pass yielded moderately cellular smears composed of scattered large fibrotic tissue fragments, some with papillary configuration [Figure 2], in a background of abundant blood. Within these tissue fragments, there were small to intermediate-sized epithelioid round cells with ill-defined cell borders, round to oval nuclei, fine granular chromatin pattern, and smooth nuclear contours. Transgressing blood vessels were evident in many of these tissue fragments [Figure 3]. In addition, there were a few sheets of small to intermediate-sized epithelial cells with round nuclei, occasional small nucleoli, and moderate amount of finely granular to foamy cytoplasm. They were arranged in pavement-type pattern, resembling pneumocytes and not associated with fibrovascular structures [Figure 4]. There was no obvious morphological distinction between the cells within the fibrovascular fragments and the cells arranged in pavement-like fashion. The third pass was hypocellular and revealed some fragments of dense collagenous tissue, some associated with round cells [Figure 5]. No mitoses or necrosis were present. There was no inflammation in the background.

- Fibrotic stromal fragment with papillary features in a background of abundant blood (Papanicolaou stain, ×100)

- Fibrovascular fragment associated with round cells (Diff-Quik stain, ×200)

- Cohesive sheets of surface cells arranged in pavement-like fashion (Diff-Quik stain, ×400)

- Dense collagenous stromal tissue associated with bland appearing round cells (×200)

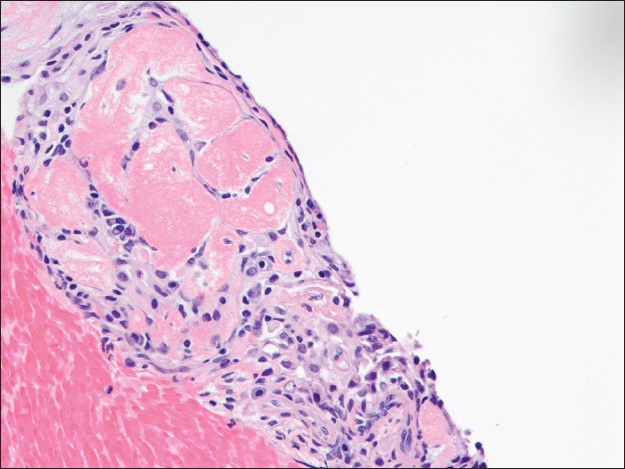

The cell block displayed many papillary structures with central hyalinized fibrosclerotic cores. These papillary fronts were lined with a single layer of small flat or low cuboidal cells [Figure 6]. Focal dystrophic calcifications were noted, correlating with the radiological findings. Within the sclerotic papillary stalks, there were scattered round to spindled cells admixed with a few small lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, and rare mast cells.

- The papillary front on the cell block lined by a single layer of flat surface cells is focally hyalinized. Scattered round cells and inflammatory cells are observed in the center of this structure (H and E, ×200)

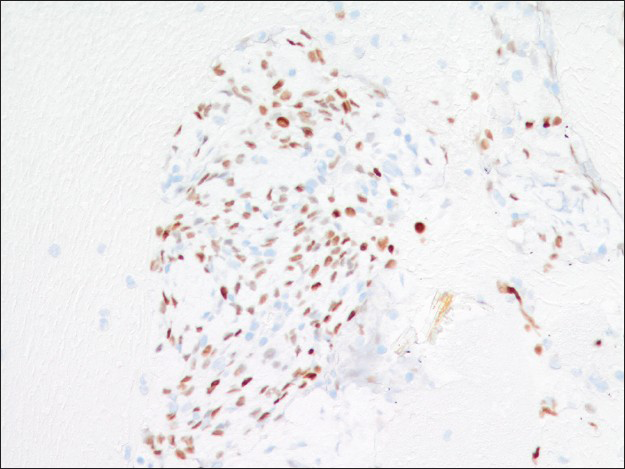

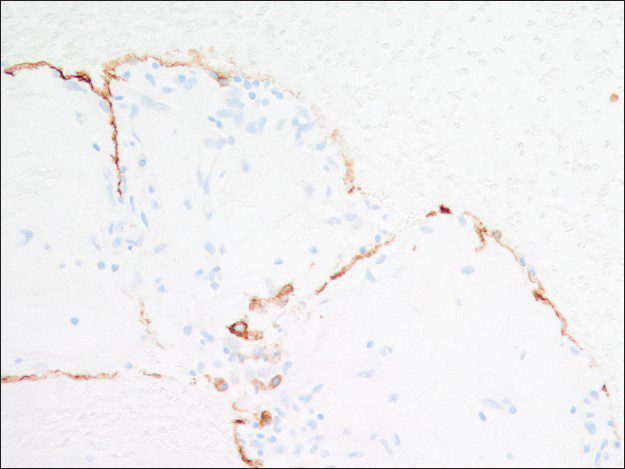

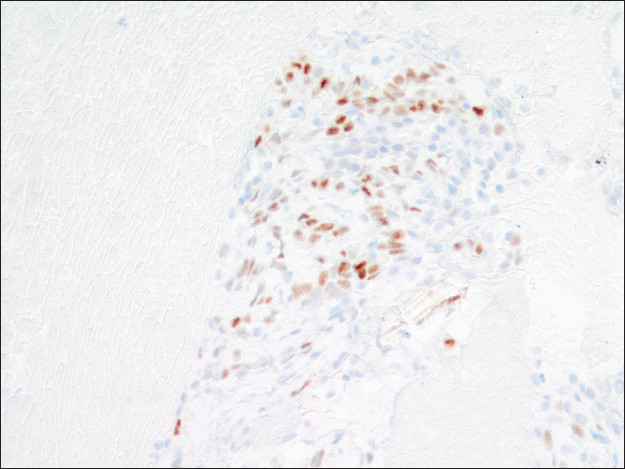

Immunohistochemical studies highlighted the dual cell population in the cell block sections. Both surface and round tumor cells were positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) [Figure 7] and negative for synaptophysin and chromogranin. In addition, the surface cells were positive for pan-cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and negative for progesterone receptor (PR), whereas the round cells within those papillary structures were negative for AE1/AE3 and positive for PR [Figures 8 and 9]. A proliferative index marker (Ki-67) showed staining in <3% of the tumor cells. The final diagnosis of sclerosing hemangioma was suggested and later confirmed by the concurrent core biopsy.

- Both surface and round cells are positive for thyroid transcription factor-1 immunostain (×200)

- AE1/AE3 immunoreactivity is present in the surface cells but not the round cells (×200)

- Progesterone receptor immunoreactivity is present in the round cells but not the surface cells (×200)

DISCUSSION

Sclerosing hemangioma occurs predominantly in females (5:1) across a wide age range (11–83 years) with a median age of 46 years. It is a rare tumor in Western populations, but in East Asians the incidence approaches that of carcinoid tumor. Most patients are asymptomatic; however, about 20% may present with cough and hemoptysis.[16] Radiologically, most lesions are located in the lower lobes, especially subpleural peripheral region. They are <3 cm with well-defined margins and occasional dystrophic calcifications.[1112] The clinical presentation in the case described herein is classic for this tumor: A middle-aged Cantonese (East Asian) woman with a well-circumscribed solitary lung nodule located in the left lower lobe. Although the clinical and radiological findings are not specific for sclerosing hemangioma, this information provides helpful clues to guide the cytological analysis.

Histologically, sclerosing hemangioma is composed of a biphasic population of cells (surface and round cells) arranged in four common morphological patterns; papillary, solid, angiomatous, and sclerotic.[16] Almost all cases of sclerosing hemangioma are composed of at least two aforementioned histological patterns. The various histological combinations of this tumor create a diagnostic challenge for FNA specimens. The difficulty in the FNA diagnosis of this tumor is further exaggerated by its rarity and the potential unfamiliarity with its cytologic features by most pathologists.

To our knowledge, a total 17 cases of sclerosing hemangioma encountered on FNA has been reported in the English literature.[1013] Many of these cases were misdiagnosed because the broad spectrum of morphologic patterns seen in this lesion can closely mimic a number of other epithelial and mesenchymal tumors.[26789101112131415] The diagnosis of sclerosing hemangioma on FNA depends on the identification of fibrovascular stromal fragments with papillary architecture and a dual cell population. The dual cell population includes bland-appearing round cells associated with fibrotic or hyalinized stromal fragments and small groups or sheets of surface cells with pneumocyte II features arranged in pavement-like fashion.[810] Mitotic figures are typically absent. Occasional nuclear pleomorphism and intranuclear pseudoinclusions may be observed. The two morphologically distinct cell populations commonly described in sclerosing hemangioma, the round cells and the larger surface cells, were inconspicuous in our case as two separate groups.[710] Instead, there was a seamless morphologic transition between these two cell types, similar to Ng et al.'s observation.[8] Other morphologic features described in sclerosing hemangioma are hemosiderin-laden macrophages, hyalinized stroma, and blood-filled cystic spaces.[10] In our case, we only identified hyalinized stroma. There were no hemosiderin-laden macrophages or blood-filled cystic spaces.

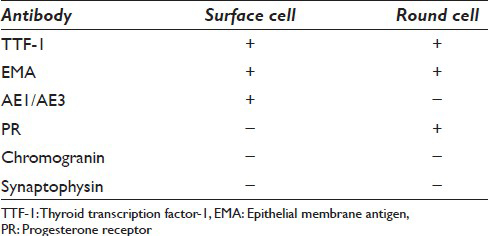

The cytologic diagnosis of sclerosing hemangioma is complicated by the histologic heterogeneity of this tumor. Depending on the area sampled by the needle, the smears can vary from hypocellular, bloody, sclerotic to hypercellular, loaded with stromal fragments and/or epithelial cell proliferation. Acquiring an adequate cell block is essential. The cell block can further shed light on the architectural pattern such as the papillary structures, and more importantly provides the opportunity for immunohistochemical studies. Sclerosing hemangioma has a unique immunohistochemical profile which highlights two distinct cell populations [Table 1]. The surface cells are consistently positive for cytokeratins AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), TTF-1, CK7, and Cam 5.2. They are also positive for pneumocyte markers, surfactant proteins A and B, and Clara cell protein.[17] In contrast, the round cells in the center of papillary stalks, although positive for TTF-1 and EMA, are usually negative for AE1/AE3 and pneumocyte markers, which suggests an undifferentiated respiratory epithelium histogenesis.[1617] However, round cells are positive for PR and estrogen receptor (ER) to a lesser degree, while surface cells are negative for both sex hormone receptors [Table 1]. The significance of PR and ER expression is unclear; however, it correlates with the female predilection of this tumor.

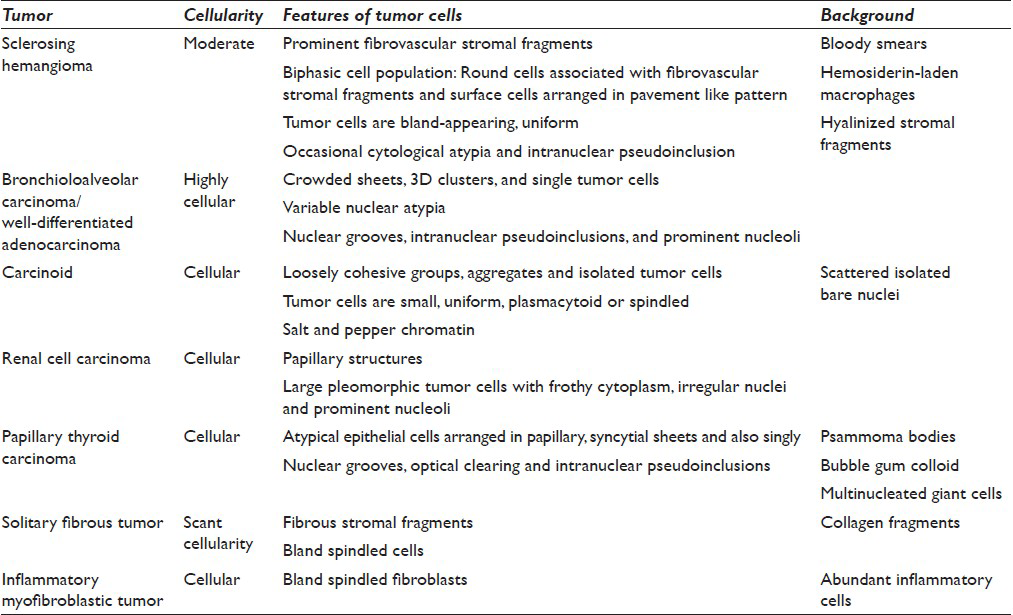

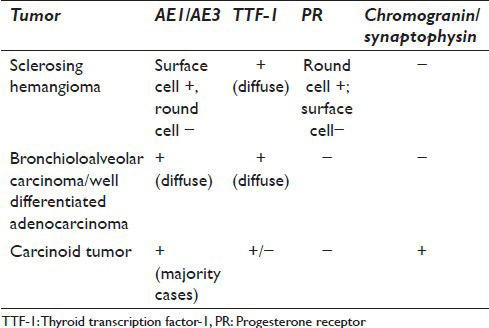

The differential diagnosis of sclerosing hemangioma on FNA is broad. Well-differentiated pulmonary adenocarcinoma/bronchioloalveolar carcinoma is the most important and dangerous pitfall, especially if the FNA sample is cellular with many surface cells. These cells may show varying degrees of atypia and intranuclear pseudoinclusions.[78101314] However, well-differentiated adenocarcinoma/bronchioloalveolar carcinoma usually occurs in an older age population. The FNA is usually more cellular with crowded clusters, sheets and many single-lying atypical cells. The cytologic atypia is more evident and extensive in adenocarcinoma, which is characterized by nuclear pleomorphism, irregular nuclear contours, and prominent nucleoli. Fibrovascular fragments are usually absent or rare. Immunohistochemical stains can aid to differentiate these two entities. However, a limited panel may not be helpful because both tumors are positive for TTF-1. Therefore, in a middle-aged female patient, with a well-defined lung mass that is TTF-1 positive and have variable morphology, sclerosing hemangioma should be considered in the differential diagnosis with adenocarcinoma. A more extensive immunoprofile including hormone receptors and AE1/AE 3 should be used to avoid an over-diagnosis of adenocarcinoma [Tables 2 and 3].

The distinction between carcinoid tumor and sclerosing hemangioma is important. Typical and atypical carcinoids are considered as malignant and the clinical management and prognosis differ from sclerosing hemangioma. Carcinoid tumor yields a uniform population of loosely cohesive groups and many isolated tumor cells with stippled (“salt and pepper”) chromatin. Papillary carcinoids and tumors with interstitial growth and prominent pneumocyte hyperplasia can mimic sclerosing hemangiomas.[9] However, fibrovascular stromal fragments are much less prominent in carcinoid tumors. In addition, immunohistochemical studies help to differentiate these two entities [Tables 2 and 3].

The differential diagnosis should also include metastatic carcinoma with papillary structures such as papillary renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC). The tumor cells in papillary RCC show obvious nuclear pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, and variable frothy to eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor cells in PTC are characterized by nuclear overlapping, nuclear grooves, and optical clearing. The distinct cytologic features of these two malignancies can be easily distinguished from bland-appearing tumor cells of sclerosing hemangioma [Table 2].

When sclerosing hemangioma presents with abundant stromal fragments, mesenchymal tumors such as solitary fibrous tumor and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor may also enter into the differential diagnosis. Mesenchymal tumors normally show abundant spindle-shaped cells instead of round cells within the fibrotic fragments. They usually lack surface cells and prominent vascular channels. Obvious inflammatory background composed of plasma cells, lymphocytes and histiocytes are characteristic for inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor but is lacking in sclerosing hemangioma. There is one case report describing an unusual sclerosing hemangioma presenting with dense spindled stromal cells.[18] Immunohistochemical studies are essential in avoiding a diagnostic pitfall in this situation [Table 2].

CONCLUSION

Sclerosing hemangioma is a rare pulmonary epithelial tumor with a dual cell population and four basic histologic patterns. The FNA diagnosis of sclerosing hemangioma is challenging, especially when one is unfamiliar with many various combinations of different histological patterns and thus should enter the differential diagnosis in solitary lung lesions. Recognizing fibrovascular stromal fragments with a papillary architecture and the biphasic cell population in a proper clinical/radiological scenario is critical for a correct diagnosis. An adequate cell block is necessary to confirm the diagnosis with immunohistochemical studies.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The author (s) declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author.

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

JZ, FZ, XJW, AS, and YS participated in drafting this manuscript, including preparing table and cytopathology figures. SK provided radiology findings and computed tomography photos of this case. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

As this is case report without identifiers, our institution does not require approval from the Institutional Review Board (or its equivalent).

Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

CT - Computed Tomography

EMA - Epithelial Membrane Antigen

ER - Estrogen Receptor

FNA - Fine Needle Aspiration

PR - Progesterone Receptor

PTC - Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma

RCC - Renal Cell Carcinoma

TTF-1 - Thyroid Transcription Factor 1.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

REFERENCES

- Fine-needle aspiration cytology of sclerosing hemangioma of the lung: Case report with immunohistochemical study. Diagn Cytopathol. 1993;9:304-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benign sclerosing pneumocytoma of lung (sclerosing haemangioma) Thorax. 1982;37:404-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- 'sclerosing haemangioma’ of the lung: An alternative view of its development. J Clin Pathol. 1973;26:390.

- [Google Scholar]

- So-called sclerosing hemangioma of the lung. An immunohistochemical, histochemical and ultrastructural study. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1988;38:627-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary sclerosing hemangioma. Report of a case with diagnosis by fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 1992;36:287-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of sclerosing hemangioma of the lung, a mimicker of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. Acta Cytol. 1986;30:51-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sclerosing hemangioma of lung: A close cytologic mimicker of pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;25:316-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine needle aspiration cytology of pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Acta Cytol. 1990;34:505-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fine-needle aspiration diagnosis of sclerosing hemangioma (pneumocytoma): Report of a case and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:242-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic features of benign solitary pulmonary nodules with radiologic correlation and diagnostic pitfalls: A report of six cases. Acta Cytol. 2009;53:201-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytology of an unusual lung tumour in a middle-aged female. 2006. Pathology. 38:66-70. Available from: http://www.journals.lww.com/pathologyrcpa/Citation/2006/38010/Cytology_of_an_unusual_lung_tumour_in_a 14.aspx

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of sclerosing hemangioma of lung: Don′t rely on fine-needle aspiration cytology diagnosis alone. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:748-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sclerosing haemangioma of lung mimicking carcinoma diagnosed by fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology. Cytopathology. 1995;6:115-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis by fine needle aspiration cytology of sclerosing haemangioma of the lung. Cytopathology. 1995;6:126-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- A clinicopathologic study of 100 cases of pulmonary sclerosing hemangioma with immunohistochemical studies: TTF-1 is expressed in both round and surface cells, suggesting an origin from primitive respiratory epithelium. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:906-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- So-called sclerosing hemangioma of lung: Current concept. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2010;14:60-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary sclerosing hemangioma presenting with dense spindle stroma cells: A potential diagnostic pitfall. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:174.

- [Google Scholar]